Abstract

Introduction:

Sitravatinib, a receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting TYRO3, AXL, MERTK receptors, and vascular epithelial growth factor receptor 2, can shift the tumor microenvironment toward an immunostimulatory state. Combining sitravatinib with checkpoint inhibitors (CPIs) may augment antitumor activity.

Methods:

The phase 2 MRTX-500 study evaluated sitravatinib (120 mg daily) with nivolumab (every 2 or 4 wk) in patients with advanced nonsquamous NSCLC who progressed on or after previous CPI (CPI-experienced) or chemotherapy (CPI-naive). CPI-experienced patients had a previous clinical benefit (PCB) (complete response, partial response, or stable disease for at least 12 weeks then disease progression) or no PCB (NPCB) from CPI. The primary end point was objective response rate (ORR); secondary objectives included safety and secondary efficacy end points.

Results:

Overall, 124 CPI-experienced (NPCB, n = 35; PCB, n = 89) and 32 CPI-naive patients were treated. Investigator-assessed ORR was 11.4% in patients with NPCB, 16.9% with PCB, and 25.0% in CPI-naive. The median progression-free survival was 3.7, 5.6, and 7.1 months with NPCB, PCB, and CPI-naive, respectively; the median overall survival was 7.9 and 13.6 months with NPCB and PCB, respectively (not reached in CPI-naive patients; median follow-up 20.4 mo). Overall, (N = 156), any grade treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) occurred in 93.6%; grade 3/4 in 58.3%. One grade 5 TRAE occurred in a CPI-naive patient. TRAEs led to treatment discontinuation in 14.1% and dose reduction or interruption in 42.9%. Biomarker analyses supported an immunostimulatory mechanism of action.

Conclusions:

Sitravatinib with nivolumab had a manageable safety profile. Although ORR was not met, this combination exhibited antitumor activity and encouraged survival in CPI-experienced patients with nonsquamous NSCLC.

Keywords: NSCLC, Tyrosine kinase inhibitor, Sitravatinib, Nivolumab, Antitumor activity

Introduction

Checkpoint inhibitor (CPI) therapy has changed the treatment landscape for NSCLC. Inhibition of immune checkpoints, either as inhibition of programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) or its ligand programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) alone, dual checkpoint inhibition in combination with anti–CTLA-4 therapy or in combination with chemotherapy, promotes an antitumor response in patients with NSCLC, exhibiting considerable clinical benefit and improved overall survival (OS) versus chemotherapy alone.1–11 Despite these advances, not all patients respond to CPI (primary resistance), and most who benefit initially develop resistance and experience disease progression (acquired resistance).12 For patients with CPI-resistant disease, whose treatment options are limited to conventional chemotherapies, there is a need to develop therapeutics to overcome this resistance.

CPI resistance is associated with various mechanisms, including defects in antigen processing, neoantigen loss, abnormal interferon-gamma signaling, coinhibitory checkpoints, and an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME).13 Regulatory T cells (Tregs), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and M2-polarized macrophages contribute to the immunosuppressive TME by suppressing pro-inflammatory T-cell responses and producing immunosuppressive cytokines.14 The abundance of these cells in the TME is regulated by a network of signaling pathways, and novel approaches are under investigation to target the TME, restore antitumor responses, and improve CPI efficacy.14,15 Sitravatinib (MGCD516), a receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), targets TYRO3, AXL, MERTK (TAM) receptors, and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2).16–18 TAM receptors have been implicated in tumor progression by functioning as negative immune regulators that dampen the activation of innate immune cells, thereby promoting an immunosuppressive TME. TAM signaling in cancer can facilitate the immune escape of malignant cells by decreasing natural killer-cell antitumor responses, reducing inflammation, and increasing the ratio of M2/M1 macrophages.16,19 Given that M2 macrophages have tumor-promoting capabilities involving immunosuppression, angiogenesis, and neovascularization, their increased number versus the immunostimulatory M1 macrophages can promote a protumor TME.20 Similarly, VEGFR2-driven angiogenesis stimulates the expansion of immunosuppressive cells including Tregs and MDSCs.21 Therefore, targeting TAM receptors and VEGFR2 using sitravatinib may shift the TME toward a less immunosuppressive state and resensitize tumors to CPI.

In preclinical murine models, sitravatinib exhibited potent antitumor activity by targeting the TME, resulting in immune cell changes that enhanced the efficacy of PD-1 blockade, including in a CPI-resistant lung cancer model.17 In a first-in-human phase 1/1b study, sitravatinib monotherapy did not have clinically meaningful antitumor activity in patients with advanced NSCLC.22 However, in the phase 1 SNOW window-of-opportunity trial in patients with oral cavity cancer, sitravatinib plus nivolumab (PD-1 inhibitor) was well tolerated and led to clinical and pathologic responses.23 The study found that sitravatinib monotherapy resulted in a less immunosuppressive TME and was associated with macrophage repolarization toward the M1 type in patients who responded to sitravatinib with nivolumab.23,24

We report the final safety and efficacy results from MRTX-500 (NCT02954991), a phase 2 study of sitravatinib with nivolumab in patients with advanced or metastatic nonsquamous (NSQ) NSCLC with disease progression on or after prior CPI (CPI-experienced) or chemotherapy (CPI-naive). This combination was evaluated in NSQ NSCLC owing to a better understanding of the safety profile of TKIs and antiangiogenic agents in this population at the time of study initiation; moreover, sitravatinib plus a CPI combination is being evaluated in squamous NSCLC in ongoing studies (NCT03666143, NCT04921358).25,26

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Treatments

MRTX-500 was an open-label, parallel, phase 2 study evaluating sitravatinib with nivolumab in patients with advanced or metastatic NSQ NSCLC who were CPI-experienced or CPI-naive (progression on or after platinum-based doublet chemotherapy). CPI-experienced patients were assessed according to the outcome of previous CPI: prior clinical benefit (PCB) (investigator-assessed and Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1 [RECIST v1.1]–defined complete response [CR], partial response [PR], or stable disease for ≥12 weeks followed by radiographic progression of the disease) versus no PCB (NPCB) (investigator-assessed radiographic progression of disease ≤12 weeks after initiation of treatment). CPI-naive patients were assessed according to PD-L1 status: no or low PD-L1 expression (<5% positivity in tumor cells) versus high PD-L1 expression (≥5% positivity) (see Supplementary Appendix for further information on how PD-L1 expression was assessed).

In the phase 1/1b 516–001 trial in patients with advanced solid tumors,22 the maximum tolerated dose for sitravatinib was identified as 150 mg once daily. The present study was designed according to the modified toxicity probability interval method;27 it was planned to begin with a dose escalation evaluation of two sitravatinib doses (120 and 150 mg, free base formulation) with nivolumab in CPI-experienced patients. Sitravatinib capsules (120 mg) were administered orally once daily in a continuous regimen of 28-day cycles. Nivolumab was administered at fixed dosing as per the package insert at 240 mg every 2 weeks or 480 mg every 4 weeks by intravenous infusion over approximately 30 minutes. Intrapatient changes to the nivolumab dosing schedule were permitted. Treatment was discontinued in case of objective disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or other reasons, including patient withdrawal, global deterioration of health, loss to follow-up, or death.

This study was approved by the institutional review board and conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines28 and the Declaration of Helsinki.29 All patients provided written informed consent.

Patients

Eligible patients were 18 years or older with histologically confirmed advanced or metastatic NSQ NSCLC, measurable disease per RECIST v1.1, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 to 2. Patients had received at least one previous treatment and had progressed on or after this treatment; for CPI-experienced patients, the most recent line of therapy included PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitors; CPI-naive patients had received previous platinum-based doublet chemotherapy. Concurrent or previous platinum-based chemotherapy was allowed for CPI-experienced patients.

Key exclusion criteria included: uncontrolled brain metastases; history of tumors testing positive for EGFR, ROS1, ALK mutations, ALK fusions, or any other well-characterized driver mutations (e.g., RET fusion, TRK alterations, BRAF mutations); unacceptable toxicity on previous CPI; or active or previously documented autoimmune disease or immunocompromising conditions.

Study Objectives and Assessments

The primary objective was to assess the clinical activity of sitravatinib with nivolumab in patients with NSQ NSCLC. Clinical activity was evaluated by investigator-assessed objective response rate (ORR) per RECIST v1.1 in the total analysis population of each cohort. Secondary objectives were to evaluate the safety and tolerability of the combination, and secondary efficacy end points including the following: (1) duration of response (DOR); (2) clinical benefit rate (CBR), defined as the percentage of patients with confirmed CR, PR, or stable disease during ≥1 on-study assessment and including ≥6 wk on-study; (3) progression-free survival (PFS); (4) OS; and (5) 1-year survival rate. All responses were confirmed in subsequent scans per RECIST v1.1.

Exploratory objectives included assessing the effect of the combination on circulating PD-L1, immune cell populations, and cytokines, and on tumor cell PD-L1 expression, tumor-infiltrating immune cells, and gene expression signatures. Further information on-study assessments and biomarker methods are available in the Supplementary Appendix.

Statistical Analyses

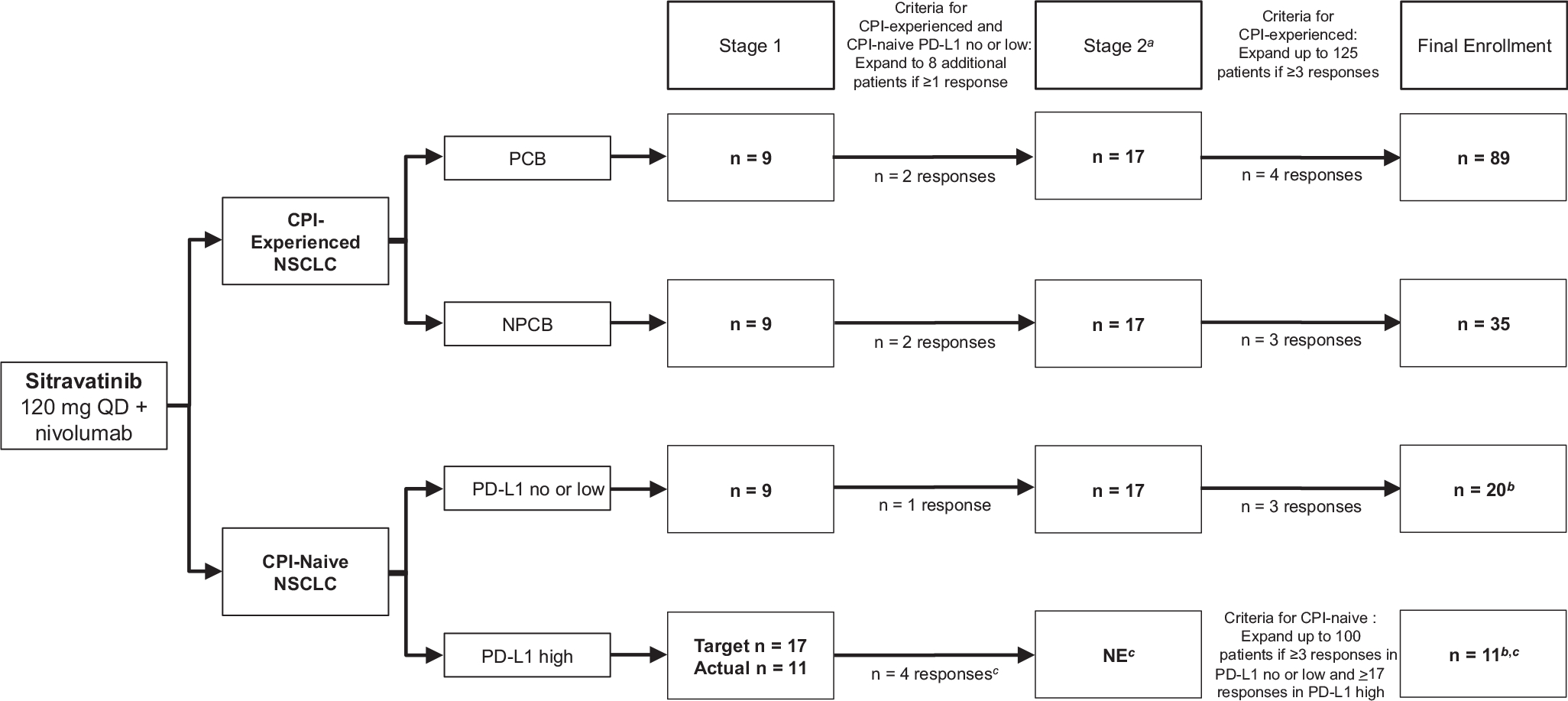

A predictive probability design was used in this study for each cohort (Fig. 1).30 In CPI-experienced patients, and CPI-naive patients with no or low PD-L1 expression, the target ORR using sitravatinib with nivolumab treatment was assumed to be 30%, and an ORR of 5% was considered uninteresting. Stage 1 of enrollment planned to include nine assessable patients; if at least one patient had an objective response, eight additional assessable patients would be enrolled in stage 2; if at least three objective responses were observed from stages 1 and 2, further investigation was warranted (Fig. 1). For stages 1 and 2, if patients discontinued treatment or withdrew consent before the first on-study disease assessment, they were considered as non-assessable. The type 1 error was 0.0466 and power was 0.9045.

Figure 1.

Study diagram of the two-stage enrollment process and responses observed for CPI-experienced and CPI-naive patients with nonsquamous NSCLC. aPatient numbers in stage 2 include those carried forward from stage 1. bEnrollment in the CPI-naive cohort was stopped owing to changes in the treatment landscape. One CPI-naive patient had unknown PD-L1 status owing to a missing laboratory sample and was included in the overall CPI-naive group only (n = 32). cCriteria for CPI-naive PD-L1 high cohort from stage 1 to stage 2: if ≥5 responses observed out of 17 assessable patients. Because four responses were observed, the PD-L1 high cohort was not evaluated past stage 1. CPI, checkpoint inhibitor; PCB, prior clinical benefit; NE, not evaluated; NPCB, no prior clinical benefit; PD-L1, programmed cell death-ligand 1; QD, once daily.

In CPI-naive patients with high PD-L1 expression, the target ORR with sitravatinib and nivolumab treatment was assumed to be 50%, and an ORR of 27% was considered uninteresting. Stage 1 of enrollment was planned to include 17 assessable patients; if at least five patients had an objective response, 27 additional assessable patients would be enrolled in stage 2. If at least 17 objective responses were observed at stage 2, further investigation was warranted (Fig. 1). The type 1 error was 0.0303 and the power was 0.9018. If the threshold for responses achieved in stages 1 and 2 were met, enrollment could be expanded to as many as 125 patients total in the CPI-experienced cohort and 100 patients total in the CPI-naive cohort (Fig. 1). Enrollment of CPI-naive patients beyond stage 2 was stopped owing to the changing treatment landscape—that is, because first-line CPI was becoming standard of care.

All patients who received at least one dose of study treatment were included in the efficacy and safety analyses. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the median DOR, PFS, OS, and the 1-year survival rate.

Results

Patients

As of January 25, 2022, the data cutoff (study start: November 7, 2016), 124 CPI-experienced (89 with PCB from CPI, 35 with NPCB) and 32 CPI-naive patients (20 with no or low PD-L1 expression, 11 with high PD-L1 expression, and one with unknown PD-L1 status) were treated (Supplementary Fig. 1). In CPI-experienced patients with PCB, the median age was 67 years, and 67.4% were former smokers (Table 1). The median number of previous regimens was two (range: 1–10) and 76.4% had received one or two previous lines of therapy. Previous CPI included pembrolizumab (56.2%) and nivolumab (37.1%), whereas 78.7% of patients had also previously received platinum-based chemotherapy. The median number of lines of therapy after platinum-based chemotherapy was one (range: 0–7). The baseline characteristics of each cohort were as expected, with the CPI-experienced and CPI-naive cohorts differing primarily with regard to previous therapy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and Baseline Characteristics of CPI-Experienced and CPI-Naive Patients With NSQ NSCLC Who Progressed on or After Previous CPI or Chemotherapy

| CPI-Experienced |

CPI-Naive |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | PCB (n = 89) | NPCB (n = 35) | Overall (N = 124) | PD-L1 no or low (n = 20) | PD-L1 high (n = 11) | Overall (N = 32)a |

|

| ||||||

| Median age, y (range) | 67.0 (37–87) | 65.0 (37–84) | 66.0 (37–87) | 66.0 (48–89) | 67.0 (30–79) | 67.5 (30–89) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||

| Male | 40 (44.9) | 18 (51.4) | 58 (46.8) | 7 (35.0) | 5 (45.5) | 12 (37.5) |

| Female | 49 (55.1) | 17 (48.6) | 66 (53.2) | 13 (65.0) | 6 (54.5) | 20 (62.5) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||

| White | 78 (87.6) | 29 (82.9) | 107 (86.3) | 16 (80.0) | 9 (81.8) | 26 (81.3) |

| Black or African American | 6 (6.7) | 2 (5.7) | 8 (6.5) | 3 (15.0) | 0 | 3 (9.4) |

| Asian | 3 (3.4) | 0 | 3 (2.4) | 1 (5.0) | 0 | 1 (3.1) |

| Other | 2 (2.2) | 4 (11.5) | 6 (4.8) | 0 | 2 (18.2) | 2 (6.2) |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | ||||||

| 0 | 22 (24.7) | 9 (25.7) | 31 (25.0) | 4 (20.0) | 4 (36.4) | 8 (25.0) |

| 1 | 60 (67.4) | 26 (74.3) | 86 (69.4) | 16 (80.0) | 7 (63.6) | 24 (75.0) |

| 2 | 7 (7.9) | 0 | 7 (5.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||||||

| Never smoker | 15 (16.9) | 8 (22.9) | 23 (18.5) | 4 (20.0) | 2 (18.2) | 6 (18.8) |

| Current smoker | 14 (15.7) | 5 (14.3) | 19 (15.3) | 3 (15.0) | 1 (9.1) | 4 (12.5) |

| Former smoker | 60 (67.4) | 22 (62.9) | 82 (66.1) | 13 (65.0) | 8 (72.7) | 22 (68.8) |

| Current stage, n (%) | ||||||

| Locally advanced | 5 (5.6) | 5 (14.3) | 10 (8.1) | 4 (20.0) | 0 | 4 (12.5) |

| Metastatic | 84 (94.4) | 30 (85.7) | 114 (91.9) | 16 (80.0) | 11 (100) | 28 (87.5) |

| Median number of prior regimens, n (range) | 2.0 (1–10) | 2.0 (1–10) | 2.0 (1–10) | 1.0 (0–3) | 1.0 (0–3) | 1.0 (0–3) |

| Number of prior regimens, n (%) | ||||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0) | 1 (9.1) | 2 (6.3)b |

| 1 | 37 (41.6) | 12 (34.3) | 49 (39.5) | 12 (60.0) | 7 (63.6) | 19 (59.4) |

| 2 | 31 (34.8) | 15 (42.9) | 46 (37.1) | 5 (25.0) | 1 (9.1) | 6 (18.8) |

| ≥3 | 21 (23.6) | 8 (22.9) | 29 (23.4) | 2 (10.0) | 2 (18.2) | 5 (15.6) |

| Prior platinum-based chemotherapy, n (%) | 70 (78.7) | 31 (88.6) | 101 (81.5) | 19 (95.0) | 10 (90.9) | 30 (93.8) |

| Cisplatin | 12 (13.5) | 5 (14.3) | 17 (13.7) | 2 (10.0) | 2 (18.2) | 5 (15.6) |

| Carboplatin | 56 (62.9) | 25 (71.4) | 81 (65.3) | 17 (85.0) | 8 (72.7) | 25 (78.1) |

| Other | 2 (2.2)c | 1 (2.9)d | 3 (2.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Median number of lines of therapy post platinum-based chemotherapy, n (range) | 1.0 (0–7) | 1.0 (0–9) | 1.0 (0–9) | NA | NA | 0 (0–1) |

| Number of lines of therapy post platinum-based chemotherapy, n (%) | ||||||

| 0 | 41 (46.1) | 15 (42.9) | 56 (45.2) | NA | NA | 27 (84.4) |

| 1 | 31 (34.8) | 15 (42.9) | 46 (37.1) | NA | NA | 5 (15.6) |

| 2 | 11 (12.4) | 2 (5.7) | 13 (10.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ≥3 | 6 (6.7) | 3 (8.6) | 9 (7.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Prior PD-1/L1 CPI, n (%) | 89 (100) | 35 (100) | 124 (100) | – | – | – |

| Nivolumab | 33 (37.1) | 13 (37.1) | 46 (37.1) | – | – | – |

| Pembrolizumab | 50 (56.2) | 19 (54.3) | 69 (55.6) | – | – | – |

| Durvalumab | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 1 (0.8) | – | – | – |

| Atezolizumab | 5 (5.6) | 3 (8.6) | 8 (6.5) | – | – | – |

| Best responsee to prior CPI, n (%) | ||||||

| Complete response | 2 (2.2) | 0 | 2(1.6) | – | – | – |

| Partial response | 36 (40.4) | 0 | 36 (29.0) | – | – | – |

| Stable disease | 51 (57.3) | 0 | 51 (41.1) | – | – | – |

| Progressive disease | 0 | 35 (100) | 35 (28.2) | – | – | – |

One CPI-naive patient had unknown PD-L1 status owing to a missing laboratory sample and was included in the overall CPI-naive group only.

Two patients who received no previous treatments were deviations from the protocol.

Other chemotherapies were cisplatin in combination with carboplatin.

Other chemotherapy was pemetrexed.

Based on investigator assessment.

CPI, checkpoint inhibitor therapy; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; NA, not available; NPCB, no prior clinical benefit; NSQ, nonsquamous; PCB, prior clinical benefit; PD-1, programmed cell death protein-1; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1.

The patients in the dose escalation cohort were the first six dose-limiting toxicity assessable patients enrolled. These patients were treated with 120 mg and reported no dose-limiting toxicities. On the basis of these data and the long-term tolerability of sitravatinib 150 mg observed in the phase 1/1b 516–001 trial,22 sitravatinib 120 mg was evaluated in all subsequent patients; therefore, these initial patients were included in subsequent efficacy and safety analyses and sitravatinib 150 mg was not evaluated (See the Supplementary Appendix for further information).

Efficacy

The responses observed in the first nine assessable patients (stage 1) and the first 17 assessable patients (stages 1 and 2) are illustrated in Figure 1. On the basis of the responses achieved in stages 1 and 2, enrollment of CPI-experienced patients was expanded to 124 patients, whereas enrollment of CPI-naive patients beyond stage 1 (PD-L1 high subgroup) and beyond stage 2 (PD-L1 no or low subgroup) was stopped at 32 owing to the changing treatment landscape.

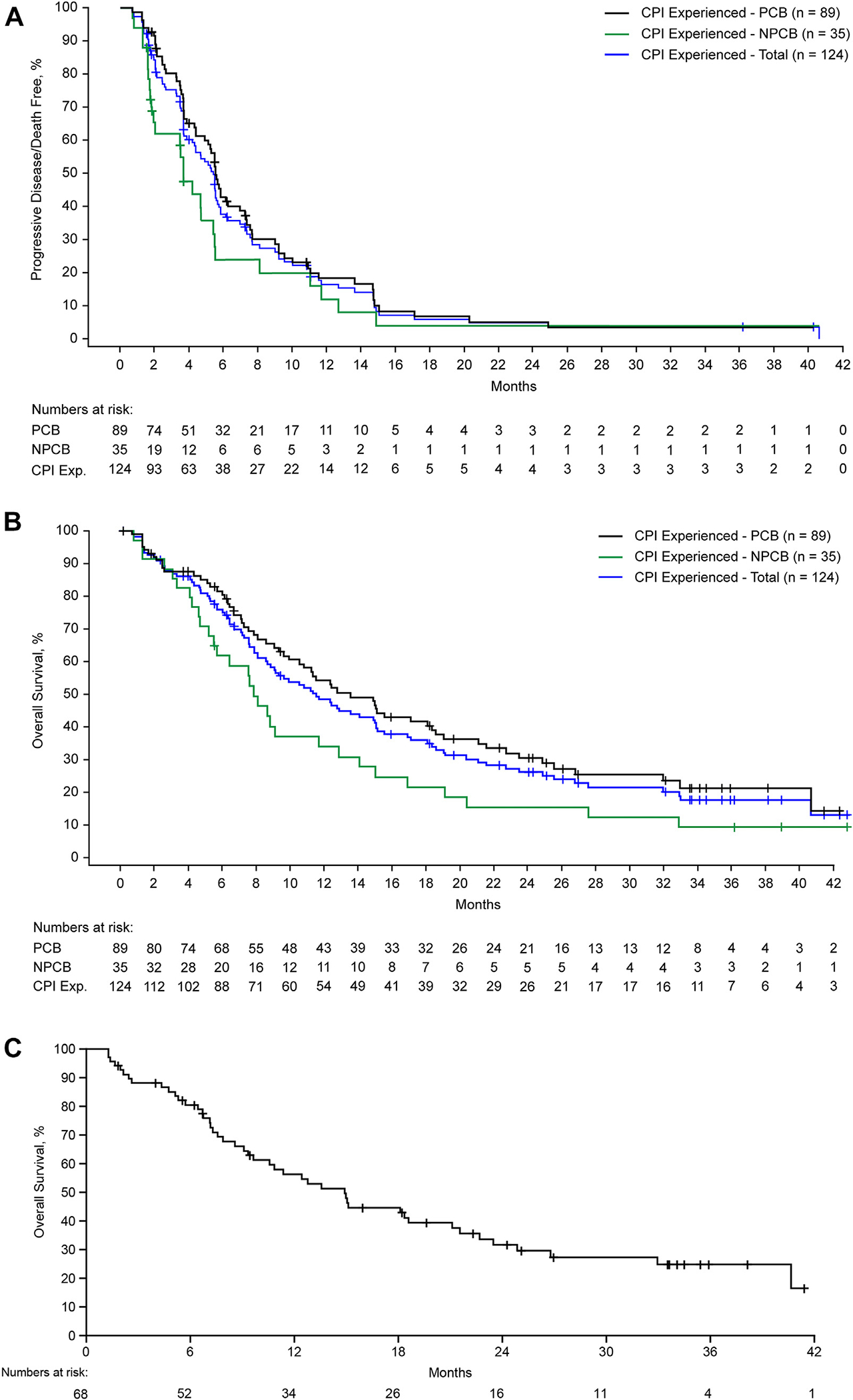

The median follow-up for CPI-experienced patients with PCB was 33.5 months. The ORR was 16.9% (15 of 89), including two CRs (2.2%) and 13 PRs (14.6%) (Table 2 and Fig. 2A). Of the 15 patients who achieved a response, 12 had at least one dose reduction, and seven had achieved a PR to their previous CPI. CBR was 78.7% (70 of 89) and the median DOR was 9.2 months (95% confidence interval [CI]: 3.6–13.1) (Table 2 and Fig. 2B). The median PFS was 5.6 months (95% CI: 4.4–7.0), with 6, 9, and 12-month PFS rates of 42.8% (95% CI: 31.6–53.4), 30.1% (95% CI: 20.2–40.7), and 18.2% (95% CI: 10.3–28.0), respectively (Table 2 and Fig. 3A). The median OS was 13.6 months (95% CI: 10.0–18.3), with an OS rate of 54.3% (95% CI: 42.9–64.3) and 30.6% (95% CI, 20.7–41.0) at 12 and 24 months, respectively (Table 2 and Fig. 3B). Notably, in the 68 patients with one or two previous lines of therapy (median follow-up = 33.6 mo), the median OS was 14.9 months (95% CI: 9.3–21.1), with 12- and 24-month OS rates of 56.2% (95% CI: 43.2–67.4) and 31.7% (95% CI: 20.2–43.7), respectively (Fig. 3C).

Table 2.

Clinical Efficacy of Sitravatinib With Nivolumab in CPI-Experienced and CPI-Naive Patients With NSCLC Who Progressed on or After Previous CPI or Chemotherapy

| CPI-Experienced |

CPI-Naive |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficacy Outcome | PCB (n = 89) | NPCB (n = 35) | Overall (N = 124) | PD-L1 no/low (n = 20) | PD-L1 high (n = 11) | Overall (N = 32)a |

|

| ||||||

| Median follow-up, mo | 33.5 | 38.9 | 34.1 | 17.5 | 30.4 | 20.4 |

| ORR | ||||||

| n (%) | 15 (16.9) | 4 (11.4) | 19 (15.3) | 4 (20.0) | 4 (36.4) | 8 (25.0) |

| 95% CI | 9.8–26.3 | 3.2–26.7 | 9.5–22.9 | 5.7–43.7 | 10.9–69.2 | 11.5–43.4 |

| BOR, n (%)b | ||||||

| CR | 2 (2.2) | 0 | 2 (1.6) | 0 | 1 (9.1) | 1 (3.1) |

| PR | 13 (14.6) | 4 (11.4) | 17 (13.7) | 4 (20.0) | 3 (27.3) | 7 (21.9) |

| SD | 55 (61.8) | 17 (48.6) | 72 (58.1) | 8 (40.0) | 7 (63.6) | 15 (46.9) |

| PD | 5 (5.6) | 9 (25.7) | 14 (11.3) | 5 (25.0) | 0 | 5 (15.6) |

| NE | 14 (15.7)c | 5 (14.3)d | 19 (15.3) | 3 (15.0) | 0 | 4 (12.5)e |

| CBR | ||||||

| n (%) | 70 (78.7) | 21 (60.0) | 91 (73.4) | 12 (60.0) | 11 (100.0) | 23 (71.9) |

| 95% CI | 68.7–86.6 | 42.1–76.1 | 64.7–80.9 | 36.1–80.9 | 71.5–100.0 | 53.3–86.3 |

| DORf | ||||||

| Median, mo (95% CI) | 9.2 (3.6–13.1) | 11.2 (9.9-NE) | 11.0 (3.7–13.1) | 7.6 (3.7-NE) | NR (5.8-NE) | 11.1 (3.7-NE) |

| PFS | ||||||

| Median, mo (95% CI) | 5.6 (4.4–7.0) | 3.7 (1.8–5.4) | 5.4 (4.2–5.7) | 6.7 (1.9–10.1) | 13.0 (5.4-NE) | 7.1 (4.0–13.1) |

| 6-mo KM estimate, % (95% CI) | 42.8 (31.6–53.4) | 23.8 (10.0–40.9) | 37.7 (28.5–46.9) | 51.8 (26.2–72.4) | 87.5 (38.7–98.1) | 62.3 (41.0–77.8) |

| 9-mo KM estimate, % (95% CI) | 30.1 (20.2–40.7) | 19.8 (7.4–36.6) | 27.4 (19.1–36.3) | 38.8 (16.3–61.1) | 62.5 (22.9–86.1) | 45.3 (25.4–63.3) |

| 12-mo KM estimate, % (95% CI) | 18.2 (10.3–28.0) | 11.9 (3.1–27.3) | 16.4 (9.8–24.5) | 23.3 (6.2–46.7) | 50.0 (15.2–77.5) | 31.7 (14.5–50.4) |

| OS | ||||||

| Median, mo (95% CI) | 13.6 (10.0–18.3) | 7.9 (5.2–11.7) | 11.5 (8.7–15.0) | NR (6.7-NE) | NR (7.8-NE) | NR (9.8-NE) |

| 12-mo KM estimate, % (95% CI) | 54.3 (42.9–64.3) | 34.0 (18.7–50.0) | 48.5 (39.1–57.2) | 59.2 (32.7–78.2) | 90.0 (47.3–98.5) | 68.6 (48.1–82.3) |

| 18-mo KM estimate, % (95% CI) | 41.6 (30.8–52.0) | 21.6 (9.6–36.8) | 35.9 (27.2–44.7) | 51.8 (25.8–72.7) | 78.8 (38.1–94.3) | 60.0 (39.1–75.7) |

| 24-mo KM estimate, % (95% CI) | 30.6 (20.7–41.0) | 15.4 (5.7–29.7) | 26.2 (18.4–34.7) | 51.8 (25.8–72.7) | 78.8 (38.1–94.3) | 60.0 (39.1–75.7) |

One CPI-naive patient had unknown PD-L1 status owing to a missing laboratory sample and was included in the overall CPI-naive group only.

A confirmed BOR of CR or PR requires a confirmatory assessment ≥4 weeks (≥28 d) because of the first CR or PR response. A CR or PR response without confirmation is summarized as SD if the assessment is >42 days after the date of the first dose and is summarized as NE if it is <42 days from the date of the first dose. For a BOR of SD, an SD assessment must be ≥42 days from the date of the first dose, otherwise, it will be summarized as NE.

A total of 13 patients had no post-baseline scans (including one patient with no measurable disease at baseline) owing to discontinuing study treatment before undergoing the first on-study disease assessment. Reasons for discontinuing study treatment included adverse events (n = 4), withdrawal by patient (n = 3), death (n = 3), global deterioration of health (n = 2), and investigator decision (n = 1). One patient had NE post-baseline scans.

Three patients had no measurable disease at baseline and two had no post-baseline scans.

Two patients had baseline-only scans, one had no baseline/post-baseline scans, and one had NE post-baseline scans.

DOR was analyzed in those patients who achieved an objective response (CR or PR).

BOR, best overall response; CBR, clinical benefit rate; CI, confidence interval; CPI, checkpoint inhibitor therapy; CR, complete response; DOR, duration of response; KM, Kaplan-Meier; NE, not assessable; NPCB, no prior clinical benefit; NR, not reached; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival; PCB, prior clinical benefit; PFS, progression-free survival; PD, progressive disease; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

Figure 2.

Efficacy of sitravatinib and nivolumab in patients with nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer previously treated with CPI. (A) Best overall response in patients with PCB from CPI (n = 89). (B) Duration of treatment in patients with PCB from CPI who responded to treatment (n = 15). One patient with confirmed PR (indicated with ‘Other’) was enrolled in a rollover study (NCT04887870). AE, adverse event; CPI, checkpoint inhibitor therapy; CR, complete response; GDH, global deterioration of health; PCB, prior clinical benefit; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; RECIST v1.1, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1; SD, stable disease.

Figure 3.

PFS and OS in patients with nonsquamous NSCLC treated with sitravatinib and nivolumab who progressed on or after prior CPI. (A) PFS in CPI-experienced patients with PCB (n = 89), NPCB (n = 35), and total (N = 124). (B) OS in CPI-experienced patients with PCB (n = 89), NPCB (n = 35), and total (N = 124). (C) OS in CPI-experienced patients with PCB from one or two prior lines of therapy (n = 68) (median follow-up = 33.6 mo). Data as of January 25, 2022. Months (x-axis) were calculated from when patients received their first dose. CPI, checkpoint inhibitor therapy; Exp., experienced; NPCB, no prior clinical benefit; OS, overall survival; PCB, prior clinical benefit; PFS, progression-free survival.

For CPI-experienced patients with NPCB, the median follow-up was 38.9 months. The ORR was 11.4% (4 of 35; all PRs) (Supplementary Fig. 2); the CBR was 60.0% (21 of 35) and the median DOR was 11.2 months (95% CI: 9.9–not estimable [NE]) (Table 2). The median PFS was 3.7 months (95% CI: 1.8–5.4), with 6, 9, and 12-month PFS rates of 23.8% (95% CI: 10.0–40.9), 19.8% (95% CI: 7.4–36.6), and 11.9% (95% CI: 3.1–27.3), respectively (Table 2 and Fig. 3A). The median OS was 7.9 months (95% CI: 5.2–11.7), with an OS rate of 34.0% (95% CI: 18.7–50.0) and 15.4% (95% CI: 5.7–29.7) at 12 and 24 months, respectively (Table 2 and Fig. 3B).

For CPI-naive patients overall (who progressed on or after platinum-based doublet chemotherapy), median follow-up was 20.4 months and ORR was 25.0% (8 of 32), including one CR (3.1%) and seven PRs (21.9%). For CPI-naive patients with known PD-L1 status, the ORR was 20.0% (four PRs) among 20 patients with no or low PD-L1 expression and 36.4% (one CR, three PRs) among 11 patients with high PD-L1 expression. Overall, the median OS was not reached and the 12- and 24-month OS rates were 68.6% (95% CI: 48.1–82.3) and 60.0% (95% CI: 39.1–75.7), respectively. For CPI-naive patients with known PD-L1 status, the median OS was not reached in either group of patients; for those patients with no/low PD-L1 expression, the 12- and 24-month OS rates were 59.2% (95% CI: 32.7–78.2) and 51.8% (95% CI: 25.8–72.7), respectively; among patients with high PD-L1 expression, the 12- and 24-month OS rates were 90.0% (95% CI: 47.3–98.5) and 78.8% (95% CI: 38.1–94.3), respectively (see Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 3 for further efficacy results in patients with no or low PD-L1 expression or high PD-L1 expression).

Safety

The median number of cycles of sitravatinib plus nivolumab was four in all CPI-experienced patients and five in CPI-naive patients. In the overall safety population (N = 156), any-grade treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) occurred in 146 of 156 patients (93.6%); the most frequent were diarrhea (54.5%), fatigue (46.2%), nausea (39.7%), and decreased appetite (34.6%) (Table 3). Grade 3 and higher TRAEs occurred in 91 of 156 (58.3%) patients; the most common were hypertension (16.7%) and diarrhea (12.8%). Investigator-assessed immune-related adverse events occurred in 68 of 156 patients (43.6%); the most frequent were hypothyroidism (19.2%), pneumonitis (4.5%), and hyperthyroidism, increased blood thyroid stimulating hormone, and rash (each in 3.8%). TRAEs in the CPI-experienced and CPI-naive cohorts were similar to the overall safety population (Table 3). No grade 5 TRAEs occurred in the CPI-experienced cohort; one CPI-naive patient experienced a TRAE (cardiac arrest) leading to death after one dose of nivolumab and four doses of sitravatinib; this patient had a history of radiotherapy to the mediastinum and three previous lines of systemic chemotherapy, including cisplatin, carboplatin, vinorelbine, paclitaxel, and pemetrexed.

Table 3.

Incidence of TRAEs in the Overall Safety Population

| CPI-Expereinced (N = 124) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCB (n = 89) |

NPCB (n = 35) |

CPI-Naive (n = 32) |

Overall (N = 156) |

|||||

| TRAEs, n (%) | Any Grade | Grade 3/4 | Any Grade | Grade 3/4 | Any Grade | Grade 3/4a | Any Grade | Grade 3/4a |

|

| ||||||||

| Any TRAEs | 80 (89.9) | 52 (58.4) | 34 (97.1) | 21 (60.0) | 32 (100) | 18 (56.3) | 146 (93.6) | 91 (58.3) |

| Most Frequent TRAEs (≥15% Any Grade in Overall Population), n (%) | Any Grade | Grade 3/4 | Any Grade | Grade 3/4 | Any Grade | Grade 3/4 | Any Grade | Grade 3/4 |

| Diarrhea | 53 (59.6) | 14 (15.7) | 13 (37.1) | 5 (14.3) | 19 (59.4) | 1 (3.1) | 85 (54.5) | 20 (12.8)b |

| Fatigue | 40 (44.9) | 4 (4.5) | 17 (48.6) | 2 (5.7) | 15 (46.9) | 3 (9.4) | 72 (46.2) | 9 (5.8) |

| Nausea | 36 (40.4) | 1 (1.1) | 12 (34.3) | 1 (2.9) | 14 (43.8) | 1 (3.1) | 62 (39.7) | 3 (1.9) |

| Decreased appetite | 30 (33.7) | 0(0) | 9 (25.7) | 1 (2.9) | 15 (46.9) | 0(0) | 54 (34.6) | 1 (0.6) |

| Hypertension | 29 (32.6) | 16 (18.0) | 8 (22.9) | 4 (11.4) | 9 (28.1) | 6 (18.8) | 46 (29.5) | 26 (16.7)b |

| Weight decreased | 27 (30.3) | 5 (5.6) | 12 (34.3) | 3 (8.6) | 5 (15.6) | 1 (3.1) | 44 (28.2) | 9 (5.8) |

| Vomiting | 26 (29.2) | 0(0) | 8 (22.9) | 2 (5.7) | 7 (21.9) | 1 (3.1) | 41 (26.3) | 3 (1.9) |

| Hypothyroidism | 18 (20.2) | 0(0) | 10 (28.6) | 0(0) | 12 (37.5) | 1 (3.1) | 40 (25.6) | 1 (0.6) |

| Dysphonia | 20 (22.5) | 0(0) | 5 (14.3) | 0(0) | 6 (18.8) | 0(0) | 31 (19.9) | 0(0) |

| PPE syndrome | 12 (13.5) | 2 (2.2) | 7 (20.0) | 1 (2.9) | 8 (25.0) | 1 (3.1) | 27 (17.3) | 4 (2.6) |

| AST increase | 14 (15.7) | 0(0) | 7 (20.0) | 2 (5.7) | 5 (15.6) | 0(0) | 26 (16.7) | 2(1.3) |

| Stomatitis | 13 (14.6) | 2 (2.2) | 7 (20.0) | 0(0) | 4 (12.5) | 0(0) | 24 (15.4) | 2(1.3) |

|

| ||||||||

| TRAEs, n (%) | Any grade | Any grade | Any grade | Any grade | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| TRAEs leading to treatment discontinuation | 12 (13.5) | 6 (17.1) | 4 (12.5) | 22 (14.1) | ||||

| TRAEs leading to sitravatinib discontinuation | 9 (10.1) | 3 (8.6) | 1 (3.1) | 13 (8.3) | ||||

| TRAEs leading to nivolumab discontinuation | 7 (7.9) | 5 (14.3) | 3 (9.4) | 15 (9.6) | ||||

One grade 5 TRAE (cardiac arrest) occurred in a CPI-naive patient.

Median time to onset of diarrhea or hypertension from day 1 of treatment was 50.0 days for patients with PCB and 42.5 days for patients with NPCB.

AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CPI, checkpoint inhibitor therapy; NPCB, no prior clinical benefit; PCB, prior clinical benefit; PPE, palmar-plantar eryth- rodysesthesia; TRAEs, treatment-related adverse events.

Overall, 22 of 156 patients (14.1%) discontinued treatment owing to TRAEs (Table 3); the most common were pneumonitis (3.2%; grade 3), fatigue, and decreased weight (each in 1.9%); discontinuation rates owing to TRAEs were 8.3% for sitravatinib and 9.6% for nivolumab. TRAEs leading to sitravatinib discontinuation included diarrhea, fatigue, and decreased weight (each in 1.3%); TRAEs leading to nivolumab discontinuation included pneumonitis (3.2%), fatigue (1.9%), and decreased weight (1.3%). In addition, TRAEs led to dose reduction/interruption (for sitravatinib defined as missing ≥1 d of study drug) of either study drug in 67 of 156 patients (42.9%); the most common were diarrhea (16.7%) and fatigue (5.8%). The median treatment intensity and dose reductions/interruptions in CPI-experienced and CPI-naive patients are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Biomarker Analyses

Exploratory analyses evaluated the mechanism of action of sitravatinib plus nivolumab. Patients with higher (≥50%) baseline PD-L1 staining tended to have a higher likelihood of deriving clinical benefit (p = 0.0552) (Supplementary Fig. 4A). In retrospective analyses, selected cancer-associated mutations and alterations that are putative targets of sitravatinib in vitro (e.g., RET, MET, CBL, AXL, KDR, and NTRK) were monitored from circulating tumor DNA in baseline plasma samples (n = 49). Most patients with clinical benefit did not have alterations in sitravatinib-targeted tyrosine kinases and only four patients with clinical benefit had these tyrosine kinase alterations (one MET mutation, two CBL mutations,31 one RET fusion) (Supplementary Fig. 4B), suggesting that clinical benefit may be derived from other mechanisms such as effects on the TME. Among the four patients who had STK11 mutations, two had the clinical benefit (Supplementary Fig. 4B). Tumor mutational burden did not correlate with clinical benefit. Flow cytometry was performed on blood samples obtained during pretreatment and at cycle 1 (n = 95), day 15 postcombination treatment (Supplementary Fig. 4C). MDSCs and Tregs were decreased, whereas CD8+ T cells and activated CD8+ T cells (CD45RA+, CD62L−) were increased in postcombination treated blood samples.

Discussion

Acquired resistance to CPI is typically defined by a period of initial clinical benefit from CPI therapy, followed by clinical or radiological progression of the disease. However, given that tumor resistance patterns to CPI therapy are often heterogenous, defining resistance has proven challenging, and there is a lack of consensus in the field.32–34

In addition, treatment options for patients who develop disease progression while receiving initial CPI and chemotherapy are limited. Because TAM receptors and VEGFR2 contribute to an immunosuppressive TME (a suggested mechanism of CPI resistance),13 targeting these receptors may have implications on cancer immunotherapy.19,21 Sitravatinib, a TKI targeting TAM receptors and VEGFR2, in combination with nivolumab, a PD-1 inhibitor, may, therefore, overcome CPI resistance and an immunosuppressive TME.17 In this phase 2 study, although the primary end point of ORR was not met, sitravatinib with nivolumab exhibited durable responses and an encouraging median OS of 13.6 months in patients with NSQ NSCLC with PCB from CPI. In contrast to unsuccessful historical attempts to combine CPI with TKIs,35,36 there were no unexpected safety signals in this study, and the safety profile was manageable with the most frequent TRAEs (e.g., fatigue, nausea, decreased appetite) and TRAEs leading to treatment discontinuation (e.g., pneumonitis) also being reported previously with nivolumab monotherapy.1 In addition, dose modification rates were similar to those seen in this class of TKIs.37

For patients receiving second-line regimens containing docetaxel with or without previous CPI, ORR is typically 9% to 27%,38 as revealed in the phase 3 REVEL39 and CANOPY-2 studies.40 A retrospective, observational study in the United States, using the Flatiron Health database, found that patients with subsequent treatment after progression on CPI and chemotherapy had a median OS of 7.3 months; the most common treatments were docetaxel plus ramucirumab (median OS = 6.5 mo) and docetaxel monotherapy (median OS = 6.7 mo).41 Moreover, the recent phase 2 Lung-MAP S1800A study found that patients receiving standard-of-care chemotherapy (typically docetaxel and ramucirumab) after progression on CPI and chemotherapy had a median OS of 11.6 months.42 In our study, patients with PCB from CPI who were treated with sitravatinib plus nivolumab had a median OS of 13.6 months, with a 12- and 24-month survival rate of 54.3% and 30.6%, respectively. In patients receiving sitravatinib and nivolumab as second or third-line treatment with a previous clinical benefit, the median OS was 14.9 months, and the 12-month survival rate was 56.2%.

The biomarker analyses conducted as part of this study support the hypothesis that sitravatinib dampens the immunosuppressive TME and may synergize with CPI therapy.17 The combination regimen led to increased levels of peripheral CD8+ and activated CD8+ T cells, while decreasing MDSCs and Treg cells, indicating that sitravatinib inhibits key immune suppressive cell populations and redirects the immune system toward an antitumor response. Most patients who derived the benefit did not have alterations in putative tyrosine kinase targets of sitravatinib, meaning that this benefit may have been achieved through a nononcogenic driver mechanism and potentially through inhibition of targets in the TME. STK11 mutation is emerging as a biomarker associated with CPI resistance in NSCLC.43,44 Interestingly, we observed that two out of four patients with STK11 mutations had a clinical benefit in our study, which might suggest an anecdotal clinical activity signal of the trial treatment in this population.

Increased baseline PD-L1 tended to be associated with clinical benefit, suggesting that sitravatinib resensitizes at least a subset of tumors to CPI and is in line with previous data suggesting that CPIs have increased activity in PD-L1-high cancers.1,43,45 Given the complexity of the TME, further research, including randomized trials, is needed to accurately select biomarkers and patients for immunotherapy and immunotherapy-based regimens.46

A clear limitation of this study is the single-arm design, which precluded patient randomization to the current standard of care. The lack of a universal definition of CPI-acquired resistance and PCB meant this was defined subjectively but on the basis of clinical judgment. Tissue biopsy collection was not a requirement, limiting our ability to perform robust tissue translational analyses to further evaluate data from those patients who derived a clinical benefit. The analyses of PD-L1 levels should be taken with caution, as these were performed on baseline samples before immunotherapy and conducted using different methods. In addition, disease progression before enrollment in CPI-experienced patients was investigator-assessed and not confirmed centrally, potentially leading to biases in the patient population.

The promising OS in this study, particularly in patients receiving sitravatinib and nivolumab as a second- or third-line treatment, has provided the basis for the ongoing phase 3 SAPPHIRE trial (NCT03906071)47; this study is evaluating sitravatinib plus nivolumab versus docetaxel in patients with advanced NSQ NSCLC who received a clinical benefit from, and subsequently progressed on, previous CPI and chemotherapy as first-or second-line treatments. Another phase 3 study (NCT04921358)26 is evaluating sitravatinib plus tislelizumab (a PD-1 inhibitor) in patients with locally advanced/metastatic NSCLC who experienced disease progression after CPI and chemotherapy. The phase 3 CONTACT-01 study (NCT04471428) evaluating cabozantinib plus atezolizumab did not meet its primary end point of OS at the final analysis,48 but further studies investigating other TKIs against TAM receptors are ongoing, such as bemcentinib (an AXL TKI) in combination with pembrolizumab in phase 2 BGBC008 trial (NCT03184571)49 and INCB081776 (an AXL/MER TKI) in a phase 1 trial (NCT03522142).50

In conclusion, sitravatinib with nivolumab exhibited favorable DOR and encouraging OS along with a manageable safety profile in patients with NSQ NSCLC who progressed on or after previous CPI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by Mirati Therapeutics, Inc. Medical writing support for the development of this manuscript, under the direction of the authors, was provided by Flaminia Fenoaltea, MSc, and Sebastiao Rodrigues, BSc, of Ashfield MedComms, an Inizio company, and funded by Mirati Therapeutics, Inc. Monoceros Biosystems provided bioinformatic support for the research-grade correlative biomarker analyses. The authors wish to thank the patients and their families who made this trial possible. In addition, they would like to give gratitude to the clinical study teams for their work and contributions including Jamie Christensen and Isan Chen for study conception and design; Emma Rui Yan for statistics support; and Alice Blaj and Yong Liu for clinical data review support.

Footnotes

CRediT Authorship Contribution Statement

Kai He: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing – Reviewing and Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration.

David Berz: Investigation, Resources, Writing – Reviewing and Editing, Supervision.

Shirish M. Gadgeel: Investigation, Resources, Writing – Reviewing and Editing.

Wade T. Iams: Investigation, Resources, Writing – Reviewing and Editing.

Debora S. Bruno: Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing – Reviewing and Editing.

Collin M. Blakely: Investigation, Writing – Reviewing and Editing.

Alexander I. Spira: Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing – Original draft, Writing – Reviewing and Editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Manish R. Patel: Resources, Writing – Reviewing and Editing.

David M. Waterhouse: Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Writing – Original draft, Writing – Reviewing and Editing, Supervision, Project administration.

Donald A. Richards: Investigation, Writing – Reviewing and Editing.

Anthony Pham: Investigation.

Robert Jotte: Data curation, Writing – Reviewing and Editing, Supervision.

David S. Hong: Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing – Reviewing and Editing, Supervision.

Edward B. Garon: Investigation, Resources, Writing – Reviewing and Editing.

Anne Traynor: Investigation, Resources, Writing – Reviewing and Editing.

Peter Olson: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – Original draft, Writing – Reviewing and Editing, Supervision, Project administration.

Lisa Latven: Writing – Reviewing and Editing, Supervision, Project administration.

Xiaohong Yan: Formal analysis, Writing – Reviewing and Editing, Visualization.

Ronald Shazer: Validation, Data curation, Writing – Reviewing and Editing, Supervision, Project administration.

Ticiana A. Leal: Investigation, Resources, Writing – Original draft, Writing – Reviewing and Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration

Disclosure: Dr. He reports financial interests, personal, and advisory board participation with Mirati Therapeutics, Inc., Perthera, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Iovance Biotherapeutics, Lyell, AstraZeneca. Dr. Berz reports financial interests, personal, and advisory board participation with Biocept and Prelude Dx; has financial interests, received personal fees, and participated in speaker’s bureau with Caris Life Sciences, Tempus, Natera, Biocept, Boehringer Ingelheim, Genentech, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Sun, and Oncocyte. Dr. Gadgeel reports advisory board participation with Genentech/Roche, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Takeda, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Janssen, Novartis, Daiichi Sankyo, Blueprint Medicines, and Mirati Therapeutics, Inc.; and Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) participation with AstraZeneca. Dr. Iams reports receiving personal fees and advisory board participation with Genentech, Defined Health, Outcomes Insights, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, GI Therapeutics, Curio Science, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Mirati Therapeutics, Inc., NovoCure, and Regeneron. Dr. Bruno reports receiving personal fees, and advisory board participation with Novartis, Eli Lilly, Mirati Therapeutics, Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Tempus Laboratory, and AstraZeneca; and receiving research funding from AstraZeneca. Dr. Blakely reports receiving personal fees and advisory board participation with Foundation Medicine, Amgen, Blueprint Medicines, Bayer, and Oncocyte; receiving financial aid for research grants (institution) from Novartis, Ignyta, Mirati Therapeutics, Inc., MedImmune, AstraZeneca, Roche/Genentech, Takeda, and Spectrum. Dr. Spira reports receiving personal fees and research funding from LAM Therapeutics and Regeneron; institutional research funding from Roche, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Astellas Pharma, MedImmune, Novartis, Newlink Genetics, Incyte, Abbvie, Ignyta, LAM Therapeutics, Trovagene, Takeda, MacroGenics, CytomX Therapeutics, Astex Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Loxo, Arch Therapeutics, Gritstone, Plexxikon, Amgen, Daiichi Sankyo, ADCT, Janssen Oncology, Mirati Therapeutics, Inc., Rubius, Synthekine, Mersana, Blueprint Medicines, Alkermes, and Revolution Medicines; personal and consulting fees from Incyte, Amgen, Novartis, Mirati Therapeutics, Inc., Gritstone, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Takeda, Janssen, Mersana, Daiichi Sankyo/AstraZeneca, and Regeneron; institutional consulting fees from Array Biopharma, AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Blueprint Medicines; personal fees for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from CytomX Therapeutics, AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Merck, Takeda, Amgen, Janssen Oncology, Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Bayer; financial aid for institutional, leadership, or fiduciary role in NEXT Oncology Virginia; and has stock or stock options in Eli Lilly. Dr. Patel reports receiving personal fees and advisory board participation with Sanofi and Juice Pharma Worldwide; and received research funding from Merck Sharp & Dohme, AstraZeneca, and Fate Therapeutics. Dr. Waterhouse reports receiving personal fees and advisory board participation with Bristol-Myers Squibb, AZ Therapies, AbbVie, Amgen, Janssen, McGivney Global Advisors, Seattle Genetics, Jazz Pharmaceutical, Exelixis, Eisai, EMD Serono, Mirati Therapeutics, Inc., Pfizer, Merck, and Regeneron/Sanofi; personal fees and Speaker’s Bureau participation with Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Janssen, and AstraZeneca; and personal and consulting fees from Amgen, Janssen, and Fresenius Kabi. Dr. Richards reports receiving personal fees and advisory board participation with Ipsen, Taiho, Seattle Genetics/Astellas, and Mirati Therapeutics, Inc. Dr. Jotte reports receiving personal fees and advisory board participation with Mirati Therapeutics, Inc. Dr. Hong reports receiving personal fees and having stocks/shares with Molecular Match and OncoResponse; personal fees and advisory board participation with Telperian; personal fees for consulting, speaker, or advisory role with Acuta, Adaptimmune, Alkermes, Alpha Insights, Amgen, AUM Biosciences, Axiom, Baxter, Bayer, Boxer Capital, BridgeBio, COG, COR2ed, Cowen, EcoR1, Erasca, F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Genentech, Gennao Bio, Gilead, GLG, Group H, Guidepoint, HCW Precision Oncology, Immunogenesis, Janssen, Liberium, MedaCorp, Medscape, Numba, Oncologia Brasil, ORI Capital, Pfizer, Pharma Intelligence, POET Congress, Prime Oncology, RAIN, SeaGen, STCube, Takeda, Tavistock, Trieza Therapeutics, Turning Point Therapeutics, WebMD, YingLing Pharma, and Ziopharm; institutional research grant from AbbVie, Adaptimmune, Adlai Nortye, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Deciphera, Endeavor, Erasca, F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Fate Therapeutics, Genentech, Genmab, Immunogenesis, Infinity, Merck, Mirati Therapeutics, Inc., Navier, NCT-CTEP, Novartis, Numab, Pfizer, Pyramid Bio, Revolution Medicine, SeaGen, STCube, Takeda, TCR2, Turning Point Therapeutics, and VM Oncology; and personal fees for travel, accommodations, and other expenses from American Association for Cancer Reasearch, ASCO, Bayer, Genmab, SITC, and Telperian. Dr. Garon reports consultant and/or advisory role with AbbVie, ABL-Bio, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dracen Pharmaceuticals, EMD Serono, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Ipsen, Merck, Natera, Novartis, Personalis, Regeneron, Sanofi, Shionogi, and Xilio; and receiving grant/research support from ABL-Bio, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dynavax Technologies, Eli Lilly, EMD Serono, Genentech, Iovance Biotherapeutics, Merck, Mirati Therapeutics, Inc., Neon, and Novartis. Dr. Olson reports receiving royalties or holding licenses for UCSF; consulting fees from Boxer Capital; having stock or stock options from Pfizer and Tango Therapeutics; and is an employee of Mirati Therapeutics, Inc. Drs. Latven, Yan, and Shazer are employees and own stocks/shares with Mirati Therapeutics, Inc. Dr. Leal reports receiving personal fees and advisory board participation with Invision First Lung, Beyond Spring Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Takeda, Genentech, Novocure, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, EMD Serono, Boehringer Ingelheim, Blueprint Medicines, and Daiichi Sankyo; personal and consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Genentech, Invision First Lung, Merck, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, EMD Serono, Boehringer Ingelheim, Blueprint Medicines, Bayer, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Daiichi Sankyo, Takeda, Eisai, Novocure, Amgen, Roche, and Regeneron; institutional research grant or contract with Pfizer, Advaxis, and Bayer. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Presented in part at the European Society Medical Oncology Annual Meeting 2021; 16 to 21 September 2021; Paris, France

Supplementary Data

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of the JTO Clinical and Research Reports at www.jtocrr.org and at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2023.02.016.

Data Sharing Statement

At Mirati Therapeutics we are committed to patient care, advancing scientific understanding, and enabling the scientific community to learn from and build on the research we have undertaken. To that end, we will honor legitimate requests for our clinical trial data from qualified researchers and investigators for conducting methodologically sound research. We will share clinical trial data, clinical study reports, study protocols, and statistical analysis plans from clinical trials for which results have been posted on clinicaltrials.gov for products and indications approved by regulators in the U.S. and/or EU. Sharing is subject to the protection of patient privacy and respect for the patient’s informed consent. In general, data will be made available for specific requests approximately 24 months after clinical trial completion from our in-scope interventional trials. For additional information on proposals with regard to data-sharing collaborations with Mirati, please e-mail us at medinfo@mirati.com.

References

- 1.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in Advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1627–1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:123–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1–positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1823–1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodríguez-Abreu D, Powell SF, Hochmair MJ, et al. Pemetrexed plus platinum with or without pembrolizumab in patients with previously untreated metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC: protocol-specified final analysis from KEYNOTE-189. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:881–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shen X, Huang S, Xiao H, et al. Efficacy and safety of PD-1/PD-L1 plus CTLA-4 antibodies ± other therapies in lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2023;30:3–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gogishvili M, Melkadze T, Makharadze T, et al. Cemiplimab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone in non-small cell lung cancer: a randomized, controlled, double-blind phase 3 trial. Nat Med. 2022;28:2374–2380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson ML, Cho BC, Luft A, et al. Durvalumab with or without tremelimumab in combination with chemotherapy as first-line therapy for metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: the phase III POSEIDON study. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:1213–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paz-Ares L, Ciuleanu TE, Cobo M, et al. First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab combined with two cycles of chemotherapy in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 9LA): an international, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:198–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Socinski MA, Jotte RM, Cappuzzo F, et al. Atezolizumab for first-line treatment of metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2288–2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.West H, McCleod M, Hussein M, et al. Atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin plus nab-paclitaxel chemotherapy compared with chemotherapy alone as first-line treatment for metastatic non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower130): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:924–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hellmann MD, Paz-Ares L, Bernabe Caro R, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2020–2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schoenfeld AJ, Hellmann MD. Acquired resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Cell. 2020;37:443–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aldea M, Andre F, Marabelle A, Dogan S, Barlesi F, Soria JC. Overcoming resistance to tumor-targeted and immune-targeted therapies. Cancer Discov. 2021;11:874–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murciano-Goroff YR, Warner AB, Wolchok JD. The future of cancer immunotherapy: microenvironment-targeting combinations. Cell Res. 2020;30:507–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Datta M, Coussens LM, Nishikawa H, Hodi FS, Jain RK. Reprogramming the tumor microenvironment to improve immunotherapy: emerging strategies and combination therapies. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2019;39:165–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akalu YT, Rothlin CV, Ghosh S. TAM receptor tyrosine kinases as emerging targets of innate immune checkpoint blockade for cancer therapy. Immunol Rev. 2017;276:165–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Du W, Huang H, Sorrelle N, Brekken RA. Sitravatinib potentiates immune checkpoint blockade in refractory cancer models. JCI Insight. 2018;3:e124184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graham DK, DeRyckere D, Davies KD, Earp HS. The TAM family: phosphatidylserine sensing receptor tyrosine kinases gone awry in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:769–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paolino M, Penninger JM. The role of TAM family receptors in immune cell function: implications for cancer therapy. Cancers (Basel). 2016;8:97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu J, Geng X, Hou J, Wu G. New insights into M1/M2 macrophages: key modulators in cancer progression. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21:389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rahma OE, Hodi FS. The intersection between tumor angiogenesis and immune suppression. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:5449–5457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bauer T, Cho BC, Heist R, et al. First-in-human phase 1/1b study to evaluate sitravatinib in patients with advanced solid tumors. Invest New Drugs. 2022;40:990–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oliva M, Chepeha D, Araujo DV, et al. Antitumor immune effects of preoperative sitravatinib and nivolumab in oral cavity cancer: SNOW window-of-opportunity study. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9:e003476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernal MO, Araujo DV, Chepeha DB, et al. SNOW: sitravatinib and nivolumab in oral cavity cancer (OCC) window of opportunity study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(15_suppl): 6569–6569. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao J, Cui J, Huang D, et al. EP08.01–070 Safety and efficacy of sitravatinib + tislelizumab in patients with PD-L1+, locally advanced/metastatic, squamous NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2022;17(suppl):S373–S374. [Google Scholar]

- 26.ClinicalTrials.gov. Tislelizumab in combination withsitravatinib in patients with locally advanced or metastatic non--small cell lung cancer. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04921358. Accessed February 7, 2022.

- 27.Ji Y, Wang SJ. Modified toxicity probability interval design: a safer and more reliable method than the 3+ 3 design for practical phase I trials. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1785–1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Food and Drug Administration. Integrated addendum toICH E6(R1): guideline for good clinical practice E6(R2). https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/E6_R2_Addendum.pdf. https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/E6_R2_Addendum.pdf. Accessed October 21, 2022. International Conference on Harmonization Vol. 2016.

- 29.World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310:2191–2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee JJ, Liu DD. A predictive probability design for phase II cancer clinical trials. Clin Trials. 2008;5:93–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tan YH, Krishnaswamy S, Nandi S, et al. CBL is frequently altered in lung cancers: its relationship to mutations in METand EGFR tyrosine kinases. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walsh RJ, Soo RA. Resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer: biomarkers and therapeutic strategies. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2020;12: 1758835920937902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kluger HM, Tawbi HA, Ascierto ML, et al. Defining tumor resistance to PD-1 pathway blockade: recommendations from the first meeting of the SITC Immunotherapy Resistance Taskforce. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8: e000398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schoenfeld AJ, Antonia SJ, Awad MM, et al. Clinical definition of acquired resistance to immunotherapy in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:1597–1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen Y, Chen Z, Chen R, et al. Immunotherapy-based combination strategies for treatment of EGFR-TKI-resistant non-small-cell lung cancer. Future Oncol. 2022;18:1757–1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patel M, Jabbour SK, Malhotra J. ALK inhibitors and checkpoint blockade: a cautionary tale of mixing oil with water? J Thorac Dis. 2018;10(suppl 18):S2198–S2201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schiller JH, Larson T, Ou SH, et al. Efficacy and safety of axitinib in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3836–3841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kurishima K, Watanabe H, Ishikawa H, Satoh H, Hizawa N. A retrospective study of docetaxel and bevacizumab as a second- or later-line chemotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Clin Oncol. 2017;7:131–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garon EB, Ciuleanu TE, Arrieta O, et al. Ramucirumab plus docetaxel versus placebo plus docetaxel for second-line treatment of stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer after disease progression on platinum-based therapy (REVEL): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014;384:665–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paz-Ares L, Goto Y, Lim WDT, et al. 1194MO - Canakinumab (CAN)+ docetaxel (DTX) for the second- or third-line (2/3L) treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): CANOPY-2 phase III results. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(suppl 5):S949–S1039. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith T, Knoll S, Martinalbo J, Ye F, Kolaei F. P10. 07 Real-world us treatment patterns and clinical outcomes in advanced NSCLC after prior platinum chemotherapy and immunotherapy. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16(suppl):S1001. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reckamp KL, Redman MW, Dragnev KH, et al. Phase II randomized study of ramucirumab and pembrolizumab versus standard of care in advanced non–small-cell lung cancer previously treated with immunotherapy—lung-MAP S1800A. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:2295–2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Skoulidis F, Goldberg ME, Greenawalt DM, et al. STK11/LKB1 mutations and PD-1 inhibitor resistance in KRAS-mutant lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:822–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pore N, Wu S, Standifer N, et al. Resistance to durvalumab and durvalumab plus tremelimumab is associated with functional STK11 mutations in patients with non-small cell lung cancer and is reversed by STAT3 knockdown. Cancer Discov. 2021;11:2828–2845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Klempner SJ, Fabrizio D, Bane S, et al. Tumor mutational burden as a predictive biomarker for response to immune checkpoint inhibitors: a review of current evidence. Oncologist. 2020;25:e147–e159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Emens LA. Predictive biomarkers: progress on the road to personalized cancer immunotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113:1601–1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.ClinicalTrials.gov. Phase 3 study of sitravatinib plus nivolumab vs docetaxel in patients with advanced nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer (SAPPHIRE). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03906071. Accessed October 21, 2022.

- 48.Exelixis Press Releasepress release. Exelixis provides update on Phase 3 CONTRACT-01 trial evaluating cabozantinib in combination with atezolizumab in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer previously treated with immunotherapy and chemotherapy. https://ir.exelixis.com/news-releases/news-release-details/exelixis-provides-update-phase-3-contact-01-trial-evaluating. Accessed February 15, 2023.

- 49.ClinicalTrials.gov. Bemcentinib (BGB324) in combinationwith pembrolizumab in patients with advanced NSCLC. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03184571. Accessed November 11, 2022.

- 50.ClinicalTrials.gov. A study exploring the safety and tolerability of INCB081776 in participants with advanced malignancies. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03522142. Accessed February 15, 2023.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

At Mirati Therapeutics we are committed to patient care, advancing scientific understanding, and enabling the scientific community to learn from and build on the research we have undertaken. To that end, we will honor legitimate requests for our clinical trial data from qualified researchers and investigators for conducting methodologically sound research. We will share clinical trial data, clinical study reports, study protocols, and statistical analysis plans from clinical trials for which results have been posted on clinicaltrials.gov for products and indications approved by regulators in the U.S. and/or EU. Sharing is subject to the protection of patient privacy and respect for the patient’s informed consent. In general, data will be made available for specific requests approximately 24 months after clinical trial completion from our in-scope interventional trials. For additional information on proposals with regard to data-sharing collaborations with Mirati, please e-mail us at medinfo@mirati.com.