Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the impact of preoperative renal impairment on the oncological outcomes of patients with urothelial carcinoma who underwent radical cystectomy.

Materials and Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of patients with urothelial carcinoma who underwent radical cystectomy from 2004 to 2017. All patients who underwent preoperative 99mTc-diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid renal scintigraphy (DTPA) were identified. We divided the patients into two groups according to their glomerular filtration rates (GFRs): GFR group 1, GFR≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2; GFR group 2, 60≤GFR<90 mL/min/1.73 m2. We included 89 patients in GFR group 1 and 246 patients in GFR group 2 and compared the clinicopathological characteristics and oncological outcomes between the two groups.

Results

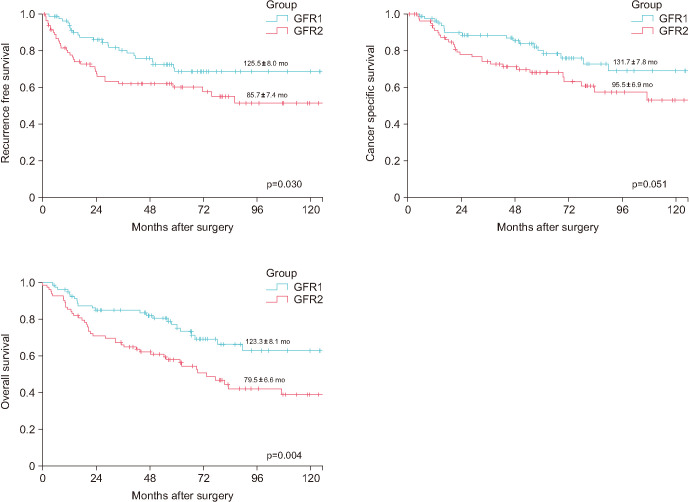

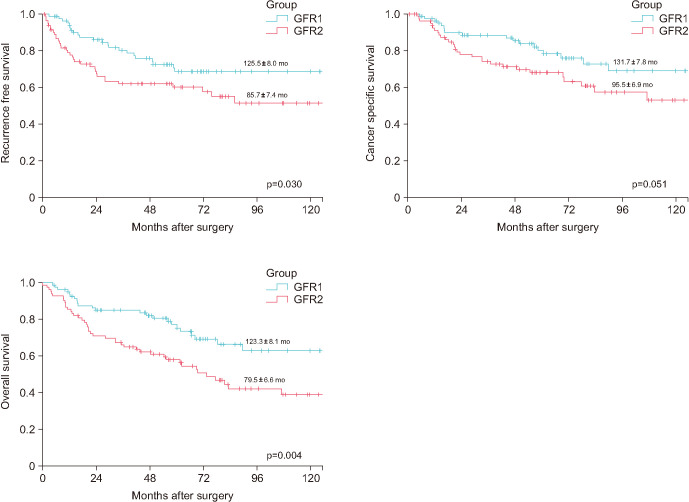

The mean time required for recurrence was 125.5±8.0 months in GFR group 1 and 85.7±7.4 months in GFR group 2 (p=0.030). The mean cancer-specific survival was 131.7±7.8 months in GFR group 1 and 95.5±6.9 months in GFR group 2 (p=0.051). The mean overall survival was 123.3±8.1 months in GFR group 1 and 79.5±6.6 months in GFR group 2 (p=0.004).

Conclusions

Preoperative GFR values in the range of 60≤GFR<90 mL/min/1.73 m2 are independent prognostic factors for poor recurrence-free survival, cancer-specific survival, and overall survival in patients after radical cystectomy compared with GFR values of ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Keywords: Bladder cancer, Glomerular filtration rates, Patient outcome assessment

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Bladder cancer is the 10th most commonly diagnosed type of cancer and the 14th leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide. Bladder cancer is four times as common in men as in women [1]. Bladder cancer is often diagnosed in middle-aged individuals; most patients are older than 65 years [2]. Older adults with bladder cancer have renal impairment as a comorbidity [3,4,5,6]. There are reports that renal impairment is associated with the recurrence of bladder cancer; in particular, it affects recurrence and progression in patients who have undergone transurethral resection of bladder tumors for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) [7,8,9]. Although the exact mechanism of action has not yet been confirmed, there have been some hypotheses involving various secretory substances in urine and other hypotheses that the urinary tract malignancy occurs as a result of a decreased urinary tract washing effect [10,11,12]. Recently, the role of prognostic factors for renal impairment has been reported in MIBC [13,14,15].

Approximately 25% of patients with bladder cancer present with MIBC [16]. The current optimal treatment for MIBC is radical cystectomy (RC) with urinary diversion. Presently, renal function is an important factor in determining the method of urinary diversion and the chemotherapy regimen [17,18]. To date, performance status, old age, tobacco-smoking, tumor stage, lymphovascular invasion (LVI), and lymph node involvement after RC are the reported prognostic risk factors [19,20]. In addition, there are not many studies on the effect of kidney function on the prognosis of patients with this condition.

Therefore, the impact of preoperative renal impairment on the prognosis of MIBC remains unelucidated. The present study aimed to investigate the association between preoperative renal function and the clinicopathological features of patients with bladder cancer, and also to assess the prognostic value of preoperative renal impairment in patients undergoing RC for MIBC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board. Patients who were treated for MIBC at our institution from 2004 to 2017 were eligible for this study. Indications for RC included MIBC, invasion of the prostatic stroma, and recurrent bladder cancer refractory to transurethral resection with intravesical chemotherapy and immunotherapy. Exclusion criteria included distant metastasis, radiotherapy, and/or synchronous or metachronous upper tract urothelial cancer.

Patients’ demographics and clinical statuses were evaluated. All patients underwent preoperative examination, including chest radiography, computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis, bone scans for disease staging, and preoperative 99mTc-diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid renal scintigraphy (DTPA). Patients were divided into two groups according to the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) as determined using DTPA: GFR group 1, GFR ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2 and GFR group 2, 60≤GFR<90 mL/min/1.73 m2.

The cystectomy specimens were processed according to standard pathology procedures, and pathology slides were reviewed by our expert genitourinary pathologists. The cystectomy specimens were pathologically staged and graded according to the 2009 American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM staging and 1973 World Health Organization grading systems.

After RC, the clinical course of patients was generally followed up every 3 months during the first year, every 6 months during the second to sixth years, and annually thereafter. Follow-up was carried out for medical history, physical examination, blood laboratory tests, and urine sedimentation, culture, and cytology. Imaging studies included chest radiography, CT of the abdomen and pelvis, and bone scanning, which were obtained at 6 months and 12 months postoperatively, and annually thereafter. Recurrence was defined as local recurrence at or below the common iliac bifurcation or distant metastasis documented by imaging and biopsy if indicated. Urothelial carcinoma that occurred in the upper urinary tract or urethra was not considered as recurrence. In this study, we tried to measure renal function through DTPA.

Clinicopathological factors were compared among the two subgroups using Pearson’s χ2-test for categorical variables and the t-test or Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables. Quantitative data were expressed as the mean±standard deviation or median (interquartile range [IQR]) with propensity-score (PS) matching. Inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) matching was performed on the basis of age, body mass index (BMI), sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), clinical stage (T, N), neoadjuvant chemotherapy, pathological stage (T, N), and LVI. Model calibration procedures were also performed and the discriminating ability of the PS matching was confirmed. Recurrence-free survival (RFS) duration was calculated as the time from RC to the first documented case of disease recurrence. The cancer-specific survival (CSS) duration was measured from the date of cystectomy to the date of death from bladder cancer. Patients who died after clinical recurrence were regarded as having cancer-specific death. The overall survival (OS) was measured from the date of cystectomy to the date of death.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for RFS, CSS, and OS were generated for the GFR groups and compared using the log-rank test. All statistical tests were two-tailed, with p<0.05 considered statistically significant. Correlations between the outcomes and variables were expressed as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A multivariable Cox proportional hazard model was used to estimate survival outcomes. All statistical analyses were carried out using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 25.0 (IBM Corp.), and SAS®, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

RESULTS

We evaluated the data of 335 patients who underwent RC before PS matching; their characteristics are listed in Table 1. The median follow-up period was 54.8 months (range, 1–169.9 mo). Of the 335 patients who underwent RC, the number of patients in GFR group 1 (GFR ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2) and GFR group 2 (60≤GFR<90 mL/min/1.73 m2) was 89 (26.6%) and 246 (73.4%), respectively. There were no significant differences in background characteristics (including sex, hypertension, DM, BMI, clinical stage [T, N], and pathological stage [T, N]) or prognosis between the groups. Patients in GFR group 2 were significantly older than those in GFR group 1 (median age, 60 y; IQR, 53–66 y vs. 66 y; IQR, 59–72 y; p<0.001). The mean GFR of GFR group 1 was 103.2±11.3 mL/min/1.73 m2, while that of GFR group 2 was 74.8±7.8 mL/min/1.73 m2. In the total cohort, GFR group 2 had significantly poorer oncological outcomes than did GFR group 1 (93.0±4.8 mo vs. 127.4±7.7 mo in RFS, p=0.011; 106.0±4.9 mo vs. 133.5±7.5 mo in CSS, p=0.019; 84.4±4.6 mo vs. 122.6±7.8 mo in OS, p<0.001). Eighty-three patients were selected after PS matching in each group as shown in Table 2.

Table 1. Patient characteristics according to the GFR group.

| Variable | Total | GFR group | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GFR group 1 | GFR group 2 | ||||

| Number of patients | 335 | 89 | 246 | ||

| Age (y) | 64 (57–71) | 60 (53–66) | 66 (59–72) | <0.001 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 291 (86.9) | 77 (86.5) | 214 (87.0) | 0.519 | |

| Female | 44 (13.1) | 12 (13.5) | 32 (13.0) | ||

| HTN | 112 (33.4) | 23 (25.8) | 89 (36.2) | 0.077 | |

| DM | 52 (15.5) | 18 (20.2) | 34 (13.8) | 0.153 | |

| Height (cm) | 164.3±7.8 | 165.1±7.7 | 164.0±7.8 | 0.227 | |

| Weight (kg) | 66.4±10.3 | 68.5±12.0 | 65.6±9.5 | 0.022 | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.5±3.3 | 25.0±3.5 | 24.3±3.3 | 0.062 | |

| GFR | 82.3±15.3 | 103.2±11.3 | 74.8±7.8 | <0.001 | |

| Clinical stage | |||||

| cT3 or T4 | 158 (47.2) | 44 (49.4) | 114 (46.3) | 0.616 | |

| >cN1 | 38 (11.3) | 10 (11.2) | 28 (11.4) | 0.970 | |

| Cisplatin-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 30 (9.0) | 7 (7.9) | 23 (9.3) | 0.674 | |

| Pathologic T stage | |||||

| ≤T2 | 193 (57.6) | 57 (64.0) | 136 (55.3) | 0.152 | |

| ≥T3 | 142 (42.4) | 32 (36.0) | 110 (44.7) | ||

| Pathologic lymph node metastasis | 74 (22.1) | 14 (15.7) | 60 (24.4) | 0.091 | |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 152 (45.4) | 36 (40.4) | 116 (47.2) | 0.276 | |

| Recurrence | 114 (34.0) | 22 (24.7) | 92 (37.4) | 0.031 | |

| Recurrence-free survival (mo) | 108.6±4.5 | 127.4±7.7 | 93.0±4.8 | 0.011 | |

| Cancer mortality | 96 (28.7) | 18 (20.2) | 78 (31.7) | ||

| Cancer-specific survival (mo) | 117.3±4.4 | 133.5±7.5 | 106.0±4.9 | 0.019 | |

| Overall mortality | 148 (44.2) | 25 (28.1) | 123 (50.0) | ||

| Overall survival (mo) | 96.9±4.3 | 122.6±7.8 | 84.4±4.6 | <0.001 | |

| Follow-up (mo) | 54.9 (17.0–79.0) | 58.3 (26.3–88.2) | 49.7 (15.9–78.1) | ||

Values are presented as number (%), median (interquartile range), or mean±standard deviation.

DM, diabetes mellitus; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; HTN, hypertension.

Table 2. Patient characteristics after propensity-score matching.

| Variable | GFR group | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GFR group 1 | GFR group 2 | |||

| Number of patients | 83 | 83 | ||

| Age (y) | 60 (53–66) | 61 (52–69) | 0.947 | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 71 (85.5) | 72 (86.7) | 0.822 | |

| Female | 12 (14.5) | 11 (13.3) | ||

| HTN | 22 (26.5) | 19 (22.9) | 0.589 | |

| DM | 15 (18.1) | 19 (22.9) | 0.442 | |

| Height (cm) | 164.8±7.9 | 163.8±8.4 | 0.448 | |

| Weight (kg) | 68.4±12.3 | 67.0±9.1 | 0.413 | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.1±3.5 | 25.0±3.1 | 0.869 | |

| GFR | 103.4±11.4 | 75.4±7.7 | <0.001 | |

| Clinical stage | ||||

| cT3 or T4 | 41 (49.4) | 41 (49.4) | 1.000 | |

| >cN1 | 10 (12.0) | 8 (9.6) | 0.618 | |

| Cisplatin-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 7 (8.4) | 8 (9.6) | 0.787 | |

| Pathologic T stage | ||||

| ≤T2 | 52 (62.7) | 50 (60.2) | 0.750 | |

| ≥T3 | 31 (37.3) | 33 (39.8) | ||

| Pathological lymph node metastasis | 14 (16.9) | 19 (22.9) | 0.331 | |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 34 (41.0) | 37 (44.6) | 0.638 | |

| Recurrence | 22 (26.5) | 34 (41.0) | ||

| Recurrence-free survival (mo) | 125.5±8.0 | 85.7±7.4 | 0.030 | |

| Cancer mortality | 18 (21.7) | 29 (34.9) | ||

| Cancer-specific survival (mo) | 131.7±7.8 | 95.5±6.9 | 0.051 | |

| Overall mortality | 23 (27.7) | 43 (51.8) | ||

| Overall survival (mo) | 123.3±8.1 | 79.5±6.6 | 0.004 | |

| Follow-up (mo) | 60.9 (32.2–87.0) | 54.9 (20.3–81.0) | ||

Values are presented as number (%), median (interquartile range), or mean±standard deviation.

DM, diabetes mellitus; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; HTN, hypertension.

The univariate Cox regression analysis showed significantly poorer RFS (HR 1.82, p=0.001), CSS (HR 1.83, p=0.020), and OS (HR 2.06, p=0.010) for patients in GFR group 2 than in patients in GFR group 1. PS-adjusted multivariate Cox regression analyses for patients in GFR group 2 demonstrated poorer RFS (HR 2.25, p=0.020), CSS (HR 2.75, p=0.010), and OS (HR 3.30, p<0.001) than in patients in GFR group 1.

IPTW-adjusted multivariate Cox regression analyses for patients in GFR group 2 demonstrated poorer RFS (HR 1.83, p<0.001), CSS (HR 1.81, p<0.001), and OS (HR 2.30, p<0.001) than in patients in GFR group 1 (Table 3).

Table 3. IPTW and PS-adjusted multivariate Cox regression models for recurrence-free survival, cancer-specific survival, and overall survival.

| Factor | Univariate | Multivariate (PS) | Multivariate (IPTW) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| RFS | GFR ≥90 | Ref 1.82 (1.14–2.89) |

0.001 | Ref 2.25 (1.14–4.44) |

0.020 | Ref 1.83 (1.49–2.25) |

<0.001 |

| 60≤GFR<90 | |||||||

| CSS | GFR ≥90 | Ref 1.83 (1.10–3.06) |

0.020 | Ref 2.75 (1.22–6.18) |

0.010 | Ref 1.81 (1.45–2.26) |

<0.001 |

| 60≤GFR<90 | |||||||

| OS | GFR ≥90 | Ref 2.06 (1.34–3.17) |

0.010 | Ref 3.30 (1.63–6.70) |

<0.001 | Ref 2.30 (1.89–2.81) |

<0.001 |

| 60≤GFR<90 | |||||||

CI, confidence interval; CSS, cancer-specific survival; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; HR, hazard ratio; IPTW, inverse probability of treatment weighting; OS, overall survival; PS, propensity score; RFS, recurrence-free survival.

Fig. 1 shows the survival curves of the PS-matched populations in both GFR groups. On the date of PS matching, the median follow-up periods were 60.9 months (IQR, 32.2–87.0 mo) and 54.9 months (IQR, 20.3–81.0 mo) for GFR groups 1 and 2, respectively. The mean RFS duration was significantly better in GFR group 1 than in GFR group 2 (125.5±8.0 mo vs. 85.7±7.4 mo, respectively; p=0.030), and the mean OS duration was significantly longer in GFR group 1 than in GFR group 2 (123.3±8.1 mo vs. 79.5±6.6 mo, respectively; p=0.004). However, the mean CSS duration was not significantly longer in GFR group 1 than in GFR group 2 (131.7±7.8 mo vs. 95.5±6.9 mo, respectively; p=0.051).

Fig. 1. Recurrence-free survival, cancer-specific survival, and overall survival outcomes stratified by glomerular filtration rate (GFR) group.

DISCUSSION

For those with MIBC in our study, despite undergoing RC with lymph node dissection, the survival rate was generally low. A comprehensive review reported local recurrence rates ranging from 30% to 54% and distant metastasis in up to 50% of cases [21]. The 5-year mortality rate of patients with MIBC remains in the range of 50% to 70% [22,23]. Risk factors for relapse and survival after cystectomy include higher age, advanced tumor stage, and the presence of nodal metastases [21,24].

Renal function is known to be one of the most important factors for decision-making for urinary diversion; however, there have been recent reports on the effect of urinary diversion on oncological outcomes [13,14,15,25]. Hamano et al. [15] previously evaluated 581 patients who underwent RC and found that preoperative chronic kidney disease (CKD; Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate [eGFR] <60 mL/min/1.73 m2) lowers the probability of survival in MIBC. Since then, there have been several studies on the relationship between the severity of renal function and bladder cancer. Matsumoto et al. [14] demonstrated that advanced preoperative CKD stage 3b (eGFR <45 mL/min/1.73 m2) is significantly associated with poor oncological outcomes of bladder cancer after RC. Similar to previous studies, Momota et al. [13] reported that patients with preoperative severe renal insufficiency (eGFR <45 mL/min/1.73 m2) have a higher risk for relapse and lower survival probability. A systematic review and meta-analysis (n=5,232) reported that MIBC patients with preoperative CKD had a significantly lower survival probability than MIBC patients without CKD after undergoing RC [26]. However, to date, no study has investigated the impact of 60≤GFR<90 mL/min/1.73 m2 compared with GFR ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2 on oncological outcomes after RC. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that preoperative 60≤GFR<90 mL/min/1.73 m2 is an independent predictor of poor RFS, CSS, and OS compared with GFR ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Although a biological mechanism between renal insufficiency and bladder cancer has not yet been established, several hypotheses are possible. CKD induces chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, metabolic disorders, and uremia-related immunodeficiency [27,28]. This adversely affects oncological outcome. Furthermore, most chemotherapy drugs are nephrotoxic, which restricts the choice of drugs. However, the precise biological mechanisms for the association between renal function and oncological outcomes of MIBC remain undetermined. As such, further studies are necessary.

Some limitations of our present study are worth noting. First, we were unable to control for selection bias and other unmeasurable confounders due to the retrospective study design at a single institution and the small size of the cohorts. We could not control the selection biases. PS and IPTW-adjusted multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed to analyze the effect of renal function on oncological outcomes. Second, GFR was evaluated using 99mTc-DTPA. Inulin clearance is the gold standard for determining the GFR; however, this method is complicated and difficult to promote in clinical practice [29]. The 99mTc-DTPA method yields highly consistent results, with a correlation coefficient of 0.97–0.996; compared with inulin clearance, it has better clinical acceptance [30].

Despite these limitations, we reported here for the first time that patients with 60≤GFR<90 demonstrated poorer RFS (HR 1.83, p<0.001), CSS (HR 1.81, p<0.001), and OS (HR 2.30, p<0.001) than patients with GFR≥90 as shown by the IPTW-adjusted multivariate Cox regression analysis.

CONCLUSIONS

Patients who underwent RC with preoperative 60≤GFR<90 mL/min/1.73 m2 had significantly higher recurrence and lower survival rates than did the patients with GFR ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2. Further research is required to assess the impact of renal function on the prognosis of patients with MIBC.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: The authors have nothing to disclose.

FUNDING: None.

- Research conception and design: Dongsu Kim, Wook Nam, and Bumjin Lim.

- Data acquisition: Dongsu Kim, Wook Nam, Yoon Soo Kyung, Dalsan You, In Gab Jeong, Bumsik Hong, Jun Hyuk Hong, Hanjong Ahn, and Bumjin Lim.

- Statistical analysis: Dongsu Kim and Wook Nam.

- Data analysis and interpretation: Dongsu Kim, Wook Nam, Dalsan You, and In Gab Jeong.

- Drafting of the manuscript: Dongsu Kim, Wook Nam, Yoon Soo Kyung, Bumjin Lim, and Dalsan You.

- Critical revision of the manuscript: In Gab Jeong, Bumsik Hong, Jun Hyuk Hong, and Hanjong Ahn.

- Supervision: Bumjin Lim.

- Approval of the final manuscript: Dongsu Kim, Wook Nam, Yoon Soo Kyung, Dalsan You, In Gab Jeong, Bumsik Hong, Jun Hyuk Hong, Hanjong Ahn, and Bumjin Lim.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. Erratum in: CA Cancer J Clin 2020;70:313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galsky MD. How I treat bladder cancer in elderly patients. J Geriatr Oncol. 2015;6:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canter D, Viterbo R, Kutikov A, Wong YN, Plimack E, Zhu F, et al. Baseline renal function status limits patient eligibility to receive perioperative chemotherapy for invasive bladder cancer and is minimally affected by radical cystectomy. Urology. 2011;77:160–165. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.03.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dash A, Galsky MD, Vickers AJ, Serio AM, Koppie TM, Dalbagni G, et al. Impact of renal impairment on eligibility for adjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy in patients with urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Cancer. 2006;107:506–513. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hatakeyama S, Koie T, Narita T, Hosogoe S, Yamamoto H, Tobisawa Y, et al. Renal function outcomes and risk factors for stage 3B chronic kidney disease after urinary diversion in patients with muscle invasive bladder cancer [corrected] PLoS One. 2016;11:e0149544. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149544. Erratum in: PLoS One 2016;11:e0151742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsao CK, Moshier E, Seng SM, Godbold J, Grossman S, Winston J, et al. Impact of the CKD-EPI equation for estimating renal function on eligibility for cisplatin-based chemotherapy in patients with urothelial cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2012;10:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kobatake K, Hayashi T, Black PC, Goto K, Sentani K, Kaneko M, et al. Chronic kidney disease as a risk factor for recurrence and progression in patients with primary non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Int J Urol. 2017;24:594–600. doi: 10.1111/iju.13389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li CE, Chien CS, Chuang YC, Chang YI, Tang HP, Kang CH. Chronic kidney disease as an important risk factor for tumor recurrences, progression and overall survival in primary non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Int Urol Nephrol. 2016;48:993–999. doi: 10.1007/s11255-016-1264-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rausch S, Hennenlotter J, Todenhöfer T, Aufderklamm S, Schwentner C, Sievert KD, et al. Impaired estimated glomerular filtration rate is a significant predictor for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer recurrence and progression--introducing a novel prognostic model for bladder cancer recurrence. Urol Oncol. 2014;32:1178–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang CH, Yang CM, Yang AH. Renal diagnosis of chronic hemodialysis patients with urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma in Taiwan. Cancer. 2007;109:1487–1492. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen KS, Lai MK, Huang CC, Chu SH, Leu ML. Urologic cancers in uremic patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;25:694–700. doi: 10.1016/0272-6386(95)90544-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ou JH, Pan CC, Lin JS, Tzai TS, Yang WH, Chang CC, et al. Transitional cell carcinoma in dialysis patients. Eur Urol. 2000;37:90–94. doi: 10.1159/000020106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Momota M, Hatakeyama S, Tokui N, Sato T, Yamamoto H, Tobisawa Y, et al. The impact of preoperative severe renal insufficiency on poor postsurgical oncological prognosis in patients with urothelial carcinoma. Eur Urol Focus. 2019;5:1066–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsumoto A, Nakagawa T, Kanatani A, Ikeda M, Kawai T, Miyakawa J, et al. Preoperative chronic kidney disease is predictive of oncological outcome of radical cystectomy for bladder cancer. World J Urol. 2018;36:249–256. doi: 10.1007/s00345-017-2141-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamano I, Hatakeyama S, Iwamurau H, Fujita N, Fukushi K, Narita T, et al. Preoperative chronic kidney disease predicts poor oncological outcomes after radical cystectomy in patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:61404–61414. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang SS, Bochner BH, Chou R, Dreicer R, Kamat AM, Lerner SP, et al. Treatment of nonmetastatic muscle-invasive bladder cancer: American Urological Association/American Society of Clinical Oncology/American Society for Radiation Oncology/Society of Urologic Oncology Clinical Practice guideline summary. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13:621–625. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2017.024919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hautmann RE. Urinary diversion: ileal conduit to neobladder. J Urol. 2003;169:834–842. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000029010.97686.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koshkin VS, Barata PC, Rybicki LA, Zahoor H, Almassi N, Redden AM, et al. Feasibility of cisplatin-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy in muscle-invasive bladder cancer patients with diminished renal function. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2018;16:e879–e892. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kluth LA, Black PC, Bochner BH, Catto J, Lerner SP, Stenzl A, et al. Prognostic and Prediction tools in bladder cancer: a comprehensive review of the literature. Eur Urol. 2015;68:238–253. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moschini M, Karnes RJ, Sharma V, Gandaglia G, Fossati N, Dell'Oglio P, et al. Patterns and prognostic significance of clinical recurrences after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: a 20-year single center experience. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42:735–743. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mari A, Campi R, Tellini R, Gandaglia G, Albisinni S, Abufaraj M, et al. Patterns and predictors of recurrence after open radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: a comprehensive review of the literature. World J Urol. 2018;36:157–170. doi: 10.1007/s00345-017-2115-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grossman HB, Natale RB, Tangen CM, Speights VO, Vogelzang NJ, Trump DL, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus cystectomy compared with cystectomy alone for locally advanced bladder cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:859–866. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022148. Erratum in: N Engl J Med 2003;349:1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stein JP, Lieskovsky G, Cote R, Groshen S, Feng AC, Boyd S, et al. Radical cystectomy in the treatment of invasive bladder cancer: long-term results in 1,054 patients. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:666–675. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.3.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chamie K, Litwin MS, Bassett JC, Daskivich TJ, Lai J, Hanley JM, et al. Urologic Diseases in America Project. Recurrence of high-risk bladder cancer: a population-based analysis. Cancer. 2013;119:3219–3227. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siddiqui KM, Izawa JI. Ileal conduit: standard urinary diversion for elderly patients undergoing radical cystectomy. World J Urol. 2016;34:19–24. doi: 10.1007/s00345-015-1706-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang B, Yu W, Zhou LQ, He ZS, Shen C, He Q, et al. Prognostic significance of preoperative albumin-globulin ratio in patients with upper tract urothelial carcinoma. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0144961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rasool M, Ashraf MA, Malik A, Waquar S, Khan SA, Qazi MH, et al. Comparative study of extrapolative factors linked with oxidative injury and anti-inflammatory status in chronic kidney disease patients experiencing cardiovascular distress. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0171561. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kato S, Chmielewski M, Honda H, Pecoits-Filho R, Matsuo S, Yuzawa Y, et al. Aspects of immune dysfunction in end-stage renal disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1526–1533. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00950208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soveri I, Berg UB, Björk J, Elinder CG, Grubb A, Mejare I, et al. SBU GFR Review Group. Measuring GFR: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64:411–424. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fleming JS, Keast CM, Waller DG, Ackery D. Measurement of glomerular filtration rate with 99mTc-DTPA: a comparison of gamma camera methods. Eur J Nucl Med. 1987;13:250–253. doi: 10.1007/BF00252602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]