Abstract

Objective:

There is mixed evidence about whether omega-3 fatty acids reduce depressive symptoms. We previously reported that four months of omega-3 supplementation reduced inflammatory responsivity to a lab-based social stressor. In another study, we showed that those with exaggerated inflammatory responsivity to a social stressor had the greatest depressive symptom increases over time, especially if they experienced frequent social stress. Here we tested whether omega-3 supplementation reduced subthreshold depressive symptoms among those who experienced frequent social stress.

Methods:

Healthy, sedentary, generally overweight middle-aged and older adults (N=138) were randomly assigned to four-months of pill placebo (n=46), 1.25 grams per day (g/d) omega-3 (n=46), or 2.5 g/d omega-3 (n=46). At a baseline visit and monthly follow-up visits, they reported depressive symptoms and had their blood drawn to assess plasma levels of omega-3 fatty acids. Participants completed the Trier Inventory of Chronic Stress at Visit 2 and the Test of Negative Social Exchange at Visit 3.

Results:

Among those who were overweight or obese, both doses of omega-3 reduced depressive symptoms only in the context of frequent hostile interactions and social tension, and 2.5 g/d of omega-3 lowered depressive symptoms among those with less social recognition (ps<.05). Findings were largely corroborated with plasma omega-3 fatty acids. No other social stress or work stress measure moderated omega-3 fatty acids’ relationship with depressive symptoms (ps>.05).

Conclusions:

Omega-3 fatty acids’ antidepressant effect may be most evident among those who experience frequent social stress, perhaps because omega-3 fatty acids reduce inflammatory reactivity to social stressors.

Keywords: Omega-3, Depressive symptoms, conflict, social, inflammation

Abstract

Número de manuscrito:

HEA-2022-0263R1

Título:

Ácido Graso Omega-3 reduce síntomas depresivos solo en grupos socialmente estresados: Un corolario de la teoría de la transducción de señales sociales de la depresión

Objevo:

Existe evidencia contradictoria acerca de si los ácidos grasos omega-3 reducen síntomas depresivos. Anteriormente reportamos que cuatro meses de suplementación de omega-3 redujo la respuesta inflamatoria a un estresor social basado en el laboratorio. En otro estudio, mostramos que aquellos con una respuesta inflamatoria exagerada a un estresor social tuvieron los mayores aumentos de síntomas depresivos con el tiempo, especialmente si experimentaron estrés social frecuente. Aquí probamos si la suplementación de omega-3 redujo los síntomas depresivos por debajo del umbral entre aquellos que experimentaron estrés social frecuentemente.

Métodos:

Adultos de edad media y/o mayores sanos, sedentarios, generalmente con sobrepeso (N=138) fueron asignados aleatoriamente a cuatro meses de placebo en píldoras (n=46), 1.25 gramos por día (g/d) de omega-3 (n=46), o 2.5 g/d de omega-3 (n=46). En la visita inicial y las visitas mensuales de seguimiento, informaron síntomas depresivos y se les extrajo sangre para evaluar los niveles plasmáticos de ácidos grasos omega-3. Los parcipantes completaron el Inventario de Estrés Crónico de Trier en la Visita 2 y la Prueba de Intercambio Social Negavo en la Visita 3.

Resultados:

Entre los que tenían sobrepeso u obesidad, ambas dosis de omega-3 redujeron síntomas depresivos sólo en el contexto de frecuentes interacciones hostiles y tensión social, y 2.5 g/d de omega-3 redujeron los síntomas depresivos entre aquellos con menos reconocimiento social (ps<.05). Los hallazgos fueron corroborados en gran medida con ácidos grasos omega-3 en plasma. Ningún otro estrés social o estrés laboral mide la relación moderada entre ácidos grasos de omega-3 y síntomas depresivos (ps>.05).

Conclusiones:

El efecto antidepresivo de los ácidos grasos omega-3 puede ser más evidente entre aquellos que experimentan estrés social frecuentemente, quizás porque los ácidos grasos omega-3 reducen la reactividad inflamatoria a los estresores sociales.

Introduction

Chronic inflammation is common in the United States. More than 30% of U.S. adults have chronically elevated inflammation (C-reactive protein > 3 mg/L), which may be present even in the absence of disease (Ong et al., 2013). This inflammation is relevant not only to physical health outcomes, but also to depressive symptoms. Inflammation can play a role in sub- or supra-threshold depressive symptoms, and even slightly elevated inflammation can be problematic (Pariante, 2021).

Subthreshold depression is common and clinically important (Cuijpers et al., 2007). Effective treatment of subthreshold depression may prevent the onset of major depressive disorder. Although proinflammatory cytokine antagonists can effectively treat intractable cases of major depressive disorder when elevated inflammation is present (Raison et al., 2013), such biologic anti-inflammatory treatments are expensive and carry risks (Bonafede et al., 2012); therefore, they are unwarranted for subthreshold depressive symptoms. Inexpensive, over-the-counter agents and dietary approaches that can reduce inflammation may be effective depression-prevention strategies.

Omega-3 fatty acids may be good candidates, as they are available in diet and supplemental forms. Although several common foods are rich in omega-3 fatty acids (e.g., salmon, mackerel, chia and flax seeds, walnuts), most Americans do not have sufficient intake from foods alone. Median intake in one nationally-representative sample was 33 mg/day (Papanikolaou et al., 2014), which is well below the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics recommendation of 500 mg/day (Vannice & Rasmussen, 2014). Among people who eat diets that are richer in omega-3 fatty acids, such as the Mediterranean diet, there is some evidence of lower depression burden (Sánchez-Villegas et al., 2013; Shafiei et al., 2019). Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation is a viable option for those who have insufficient dietary intake, as it is safe and well-tolerated. It can reduce basal levels of inflammation (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2012) while also dampening inflammatory responsivity to acute social stress (Madison et al., 2021a).

In line with its anti-inflammatory effect, multiple meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials indicate that omega-3 fatty acid supplementation reduces depressive symptoms (Liao et al., 2019; Mocking et al., 2016). In these randomized controlled trials, omega-3 fatty acid supplementation has a medium effect size on depressive symptoms, compared to placebo, with certain subgroups finding more benefit (i.e., antidepressant users) (Liao et al., 2019; Mocking et al., 2016). However, several individual randomized controlled trials, including two from our lab (Kiecolt-Glaser, Belury, Andridge, Malarkey, & Glaser, 2011; Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2012), have failed to find an anti-depressant effect. One explanation for these null findings is that participants’ depressive symptoms were quite low upon entry into the trials (Kiecolt-Glaser, Belury, Andridge, Malarkey, & Glaser, 2011; Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2012). The most up-to-date Cochrane review indicates that omega-3 fatty acid supplementation may only reduce depressive symptoms among those with more severe depression (Appleton et al., 2021). This observation suggests that omega-3 fatty acid supplementation may be a useful depression treatment strategy. However, it does not preclude the possibility that omega-3 supplementation may reduce subthreshold depressive symptoms among a subgroup, such as those with more frequent stress exposure.

In light of the Social Signal Transduction Theory of Depression, omega-3 fatty acids’ antidepressant effect may be most evident among those who experience frequent social stress (Slavich & Irwin, 2014). This theory posits that those who have elevated inflammatory reactivity to social stress, as well as frequent exposure to social stress, will have the greatest depressive symptom increases across time (Slavich & Irwin, 2014). Using data from two distinct samples, each with a unique laboratory social stressor – one involving conflict with a marital partner and the other involving negative evaluation by a panel of unfamiliar judges (i.e., The Trier Social Stress Test; TSST) – our lab provided evidence in support of this theory (Madison et al., 2021b). Notably, only among those who experienced frequent social stress, especially conflict or exclusion-related stress, did a heightened inflammatory response to acute stress predict depression symptom increases in the following months. This relationship did not hold for those who experienced frequent non-social stress. Similarly, after administering a typhoid vaccine or saline placebo to breast cancer survivors, we found that those who reported more frequent angry, insensitive, or interfering interactions in their daily lives reported more sadness and pain following inflammatory increases (Madison et al., in press). In contrast, non-social stress did not sensitize these women to inflammation’s effect on mood and pain. Thus, across samples, laboratory paradigms, timeframes, and inflammatory stimuli, we have found that chronic or repetitive conflict and exclusion-related stress increases psychological vulnerability to inflammation.

Social stressors can also trigger an inflammatory response, but this response is not unique to social stress. Indeed, meta-analytic evidence suggests that there is not a significant difference between inflammatory response magnitude for social threats versus other types of stressors (Marsland et al., 2017). Our lab showed that omega-3 fatty acid supplementation can reduce proinflammatory cytokine reactivity surrounding the TSST speech stressor (Madison et al., 2021a), yet even though our paradigm did not include a non-social stressor, omega-3 may also reduce inflammatory responses to non-social stressors. Nonetheless, because omega-3 reduces inflammatory responses to acute stress, we suspect that it should have a more potent effect on mood among those who are more psychologically vulnerable to the effects of inflammation (i.e, the socially-stressed).

The Current Study

This study features secondary, exploratory analyses of a parent randomized, placebo-controlled trial of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation among sedentary, overweight adults, which found that 2.5 g/d and 1.25 g/d omega-3 supplementation reduced oxidative stress and basal inflammation but not depressive symptoms, compared to placebo (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2012, 2013). The parent study recruited overweight but otherwise healthy adults because they are at an increased risk for heightened inflammation and depression (Milaneschi et al., 2019; Pereira-Miranda et al., 2017). The current study follows up on the parent trial’s null results for depressive symptoms by exploring individual difference factors that could moderate omega-3’s effect. The first aim was to investigate social stress as a moderator of the relationship between omega-3 fatty acid supplementation and depressive symptoms. Specifically, we hypothesized that four months of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation would reduce depressive symptoms among those who experienced a higher frequency of social stress – in a dose-response manner. Also, we predicted that observed effects would be specific to social stress, compared to other types of stress (i.e., work-related stress), and that they would be stronger for conflict-related social stress than for other types of social stress (i.e., social overload). As an additional test, we substituted plasma levels of omega-3 fatty acids for supplementation group, and our hypotheses paralleled those above.

Research Design and Methods

Power Analysis

The most recent Cochrane meta-analysis found that omega-3 fatty acid supplementation has a small-to-modest benefit for depressive symptomology, compared to placebo (standardized mean difference= −0.30) (Appleton et al., 2021). We previously reported that social stress – especially social stress related to conflict and tension – was moderately related to depressive symptoms (.35<rs<.61) (Madison et al., 2021). A sensitivity analysis with G*Power 3.1.9.4 revealed that the smallest effect size that we could detect is f2=.11 given the established sample size of 138 participants, assuming an alpha level of 0.05 with seven predictors (main effects, interaction effect, and covariates listed below). This small-to-medium effect size is on par with the main effects above; however, it is important to note that the effect size of the interaction is not contingent on the main effects, and no prior work has tested the interactions of interest.

Participants and Research Protocol

Details about the participants, supplements, and procedure are found in the parent publication (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2012). In short, at a screening visit, trained experimenters administered the Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – IV (SCID-IV) to assess current and lifetime mood disorder history. The SCID-IV was incorporated after the first several screening visits, so SCID-IV data was not obtained for 15 participants. They were also screened for the following health conditions and medication usage, which were grounds for exclusion: psychoactive drugs, lipid-altering drugs, cardiovascular medications, steroids, prostaglandin inhibitors, heparin, warfarin, regular use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs other than a daily aspirin, substance abuse (including smoking), pregnancy, diabetes, current omega-3 fatty acid supplementation, digestive disorders, convulsive disorders, autoimmune and/or inflammatory diseases. Individuals were also excluded if they typically engaged in two or more hours of vigorous physical activity per week or had a body mass index (BMI) below 22.5 or over 40. The Ohio State University Institutional Review Board approved the study, and all participants provided written consent.

The 138 healthy, sedentary, generally overweight and obese middle-aged and older adults who were deemed eligible were randomly assigned to the placebo group (n=46), the 1.25 grams per day (g/d) omega-3 supplementation group (n=46), and the 2.5 g/d omega-3 supplementation group (n=46). Participants completed questionnaires and had their blood drawn to assess omega-3 fatty acid levels at the baseline visit as well as at one follow-up visit for each month of the four-month trial, for a total of five visits. Also at the baseline visit, participants’ sagittal abdominal diameter was measured to provide data on abdominal fat. Prior publications from this randomized, controlled trial have shown that four months of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation: (1) lowered basal IL-6 and TNF-α levels (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2012); (2) drove down oxidative stress (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2013); (3) reduced responsivity of key cellular aging biomarkers, including IL-6, during and after a laboratory speech stressor (Madison et al., 2021a); and (4) did not lower depressive symptoms, on average, across the entire sample (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2012).

Self-Report Measures

At each visit, the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) measured the frequency of depressive symptoms over the past week (Radloff, 1977) (0.84 < αs < 0.91 at each visit). A cut score of 16 was used to index clinically significant depressive symptoms (Weissman et al., 1977). At Visit 2, the 57-item Trier Inventory of Chronic Stress (TICS-S) (Schulz & Schlotz, 2002), assessed frequency of work-related and interpersonal chronic stressors over the past three months, using a five-point Likert scale ranging from “never” (0) to “very often” (4) (α=0.96). Five social stress subscales (social overload, lack of social recognition, social tension, performance pressure, and social isolation) indexed interpersonal stress, and three work stress subscales (work overload, work dissatisfaction, and overextended at work) measured non-interpersonal stress. Subscales ranged in length from four to nine items, which were summed for the total subscale score. Frequency of interpersonal conflict with important others over the past month was assessed with the revised 18-item Test of Negative Social Exchange (TENSE) scale at visit 3 (Ruehlman & Karoly, 1991) (α=0.93). The subscales included hostility, ridicule, insensitivity, and interference, and ranged in length from three to six items. On a Likert scale, participants reported how often various tense interpersonal interactions occurred in the past month, spanning from ‘not at all’ (0) to ‘about every day’ (4). Items were averaged, such that the score for each subscale ranged from 0 to 4.

Omega-3 Fatty Acid Levels in Plasma

Chloroform: methanol (2:1, v/v) with 0.2 vol. 0.88% KCl was used to extract lipids from plasma (Bligh & Dyer, 1959). To prepare fatty acid methyl esters of the fractions, they were incubated with tetramethylguanidine at 100 °C (Shantha et al., 1993) and analyzed by gas chromatography (Shimadzu, Columbia, MD) using a 30-m Omegawax 320 (Supelco-Sigma) capillary column. The helium flow rate was 30 ml/min and oven temperature was held at 175 °C for 4 min and increased to 220 °C at a rate of 3°C/min as previously described (Belury & Kempa-Steczko, 1997). Retention times were compared to authentic standards for fatty acid methyl esters (Supelco-Sigma, St. Louis, MO and Mireya, Inc., Pleasant Gap, PA). For this study, the variable of interest was the sum of omega-3 fatty acids (Alpha linolenic Acid, Stearidonic Acid, Eicosatetraenoic Acid, Eicosapentaenoic Acid, Docosapentaenoic Acid, Docosahexaenoic Acid) as a percentage of plasma fatty acids.

Analytic Strategy

We first performed zero-order correlations between variables of interest at the baseline visit. We also conducted analysis of variance and chi-square to see whether supplementation groups differed on variables of interest. If a chi-square test was significant, we then calculated cell percentages and adjusted residuals (z-scores), which were converted to chi-square values (z-score2) to calculate p-values (Garcia-Perez & Nunez-Anton, 2003). If an analysis of variance test was significant, least significant difference post-hoc comparisons were performed. The TENSE variables were not normally distributed, so the Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance tested for group differences.

For the primary hypothesis, we used generalized estimating equation (GEE) models with robust standard error estimates (Ballinger, 2004; Zeger & Liang, 1986) to test whether the three-way interaction of supplementation group by stress by visit predicted depressive symptoms. GEE models were appropriate for these repeated measures analyses because they modeled participants’ average responses, thereby providing efficient estimates of how much the average response changed for every one-unit increase in a predictor variable (Ballinger, 2004; Zeger & Liang, 1986). Importantly, measures of social stress and non-social stress were run in separate models to determine whether any observed effects were unique to social stress. When the three-way interaction was non-significant, it was removed from models to test the two-way interaction of supplementation group by social stress, controlling for visit, to examine whether omega-3 fatty acids’ antidepressant effect depended on social stress regardless of supplementation duration. In a second round of analyses, we used the same modelling strategy, but this time substituting total plasma omega-3 fatty acid levels for supplementation group. Blood was collected at each visit, so we used this time-varying variable in the interaction with stress and did not include visit in the interaction (but statistically adjusted for it) because we did not expect the effect of time-varying plasma omega-3 on depressive symptoms, conditioned on stress levels, to vary by visit. The TICS was assessed at Visit 2, so in these models, depressive symptoms at Visits 2 through Visit 5 were modeled. The TENSE was completed at Visit 3, so in these models, depressive symptoms at Visits 3 through 5 were modeled. We also performed the following pre-planned contrasts: (1) between-group mean differences in depressive symptoms at Visit 5 at high and low levels of social stress 25th and 75th percentiles); (2) within-group changes in depressive symptoms at high and low levels of social stress from the visit in which stress was assessed to Visit 5; and (3) overall group means of depressive symptoms at high and low social stress (pooled across time points).

Models adjusted for the covariates used in our prior publications from this randomized, controlled trial – age, sagittal abdominal diameter, and sex. We additionally adjusted for baseline depressive symptoms because workload (p=.003), work discontentment (p<.0001), feeling overextended at work (p<.0001), insensitive interactions (p=.04), social overload (p=.001), lack of social recognition (p=.003), social tension (p<.0001), and social isolation (p<.0001) – but not other stress measures (ps>.08) – positively tracked with baseline depressive symptoms; thus, we wanted to ensure that any observed moderation effect by stress was not just due to the fact that stressed participants had more room for improvement in depressive symptoms.

Two participants were lost to follow-up (n=1 in placebo, n=1 in 1.25 g/d) and three (n=1 in placebo, n=2 in 2.5 g/d) discontinued the intervention. Of these five participants, three did not have enough data to be included in models. Also, one participant was missing a sagittal abdominal diameter measurement and therefore was excluded from all models. Therefore, in models that include TENSE subscales, 134 participants were included. We decided to incorporate the TICS after some participants had completed Visit 2, so in these models, there were 130 people. Overall, 91% of the participants were overweight using the BMI cut point of 25 kg/m2. Heightened systemic inflammation is a common underlying factor in both obesity and some cases of depression, so the relationships of interest may be especially strong among those who are overweight. Therefore, we conducted post-hoc analyses that excluded the 13 participants who were not overweight from all the primary models. Two-tailed tests of significance were conducted and all alpha levels were set at α = 0.05. Data was analyzed with SAS version 9.4 (Armonk, NY).

Results

Randomization Check

Treatment groups were different in terms of education (χ2(4) =10.78, p=.029); upon further inspection, a lower percentage of individuals in the 2.5 g/d supplementation group identified as college graduates (χ2 (1)= 9.67, p=.002) likely because a higher percentage of individuals in this group identified as attending graduate or professional school (χ2 (1)= 5.81, p=.016). However, supplementation groups did not differ on household annual income (p=.31). Importantly, groups did not differ on baseline depressive symptoms (p=.97), mood disorder history (p=.56), prevalence of clinically significant depressive symptoms (CES-D ≥ 16, p=.40), BMI (p=.21), sagittal abdominal diameter (p=.18), or plasma omega-3 fatty acid levels (p=.28) (Table 1). Social isolation differed across groups (F(2, 130)=3.85, p=.024), in that the 1.25 g/d group reported lower social isolation than the placebo (p=.037) and 2.5 g/d groups (p=.010), but groups did not differ on any other stress measure (ps>.19) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics.

| N | Placebo M(SD) or n(%) | 1.25 g/d M(SD) or n(%) | 2.5 g/d M(SD) or n(%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Age (years) | 138 | 51.1 (8.6) | 51.1 (8.0) | 51.0 (6.7) | |

| Female | 138 | 36 (78%) | 28 (61%) | 29 (63%) | |

| Race | 138 | ||||

| White | 33 (72%) | 39 (85%) | 37 (80%) | ||

| Black | 9 (20%) | 5 (11%) | 8 (17%) | ||

| Asian | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | ||

| Other | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 137 | 30.0 (4.0) | 31.6 (4.8) | 30.6 (4.1) | |

| Sagittal abdominal diameter (cm) | 137 | 22.8 (3.2) | 23.9 (3.4) | 22.9 (2.9) | |

| CES-D continuous score | 138 | 7.7 (9.1) | 7.7 (8.7) | 7.4 (6.4) | |

| CES-D cut score (% above) | 138 | 6(13%) | 7(15%) | 3(7%) | |

| Mood disorder history (% yes) | 123 | 16(39%) | 17(40%) | 20(50%) | |

| Plasma omega-3 (% of total fatty acids) |

132 | 3.7 (0.8) | 3.9 (0.8) | 4.0 (1.1) | |

| Education* | 138 | ||||

| High school graduate or some college | 13 (28%) | 11 (24%) | 15 (33%) | ||

| College graduate | 22 (48%) | 21 (46%) | 9 (19%) | ||

| Graduate school | 11 (24%) | 14 (30%) | 22 (48%) | ||

| Household income | 138 | ||||

| <$50,000 | 19 (41%) | 15 (33%) | 11 (24%) | ||

| $50,000 - $100,000 | 17 (37%) | 19 (41%) | 25 (54%) | ||

| >$100,000 | 8 (17%) | 10 (22%) | 6 (13%) | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 2 (4%) | 2 (4%) | 4 (9%) | ||

p<.05 chi-square or anova comparison across groups; g/d = grams per day; CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations of Stress Variables

| Placebo | 1.25 g/d | 2.5 g/d | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| n | M(SD) | n | M(SD) | n | M(SD) | |

|

| ||||||

| Hostile interactions (TENSE) | 45 | .78(.93) | 46 | .96(.86) | 44 | .85(.79) |

| Ridicule interactions (TENSE) | 45 | .31(.68) | 46 | .28(.48) | 44 | .27(.50) |

| Insensitive interactions (TENSE) | 45 | .84(.99) | 46 | .75(.78) | 44 | .77(.77) |

| Interfering interactions (TENSE) | 45 | .61(.88) | 46 | .48(.54) | 44 | .45(.44) |

| Social overload (TICS) | 44 | 9.50(4.70) | 44 | 9.84(4.40) | 43 | 9.65(5.18) |

| Social tension (TICS) | 44 | 4.77(3.48) | 44 | 5.34 (3.37) | 43 | 5.51(3.22) |

| Social isolation (TICS)* | 44 | 7.48(4.67) | 44 | 5.52(3.83) | 43 | 7.95(4.48) |

| Lack of social recognition (TICS) | 44 | 4.80(3.22) | 44 | 4.71(3.18) | 43 | 5.02(2.83) |

| Work overload (TICS) | 44 | 11.93(7.29) | 44 | 12.07(6.55) | 43 | 12.74(6.04) |

| Work discontent (TICS) | 44 | 9.77(5.11) | 44 | 8.80(4.87) | 43 | 9.95(4.64) |

| Performance pressure (TICS) | 44 | 13.48(6.63) | 44 | 15.02(6.28) | 43 | 15.81(6.30) |

| Overextended at work (TICS) | 44 | 5.89(3.87) | 44 | 4.93(3.93) | 43 | 5.58(2.81) |

g/d = grams per day; TENSE = Test of Negative Social Exchange, measured at Visit 3; TICS = Trier Inventory of Chronic Stressors, measured at Visit 2;

p<.05 mean difference across groups

Descriptive Statistics

Participants were middle-aged (M=51.04, SD=7.75), overweight and obese (BMI M=30.69, SD=4.33), and physically healthy, given the strict exclusionary criteria. Most were female (n=93, 67%), White (n=109, 79%), not Hispanic or Latino (n=132, 96%), and married (n=92, 67%). In terms of socioeconomic status, most participants had earned a college degree (72%) and reported a household annual income above $50,000 (62%). At the screening visit, 38% had a history of a mood disorder or adjustment disorder with depressive features, and 12% had clinically significant depressive symptoms as indexed by the CES-D cut score.

Covariates

Those who had more depressive symptoms at baseline also had more depressive symptoms during the intervention (B=0.51, SE=0.11, χ2 (1)=14.31, p=.0002). Sagittal abdominal diameter (p=.24), age (p=.64), and sex (p=.09) were unrelated to depressive symptoms.

Primary Results

Social Stress and Supplementation Group

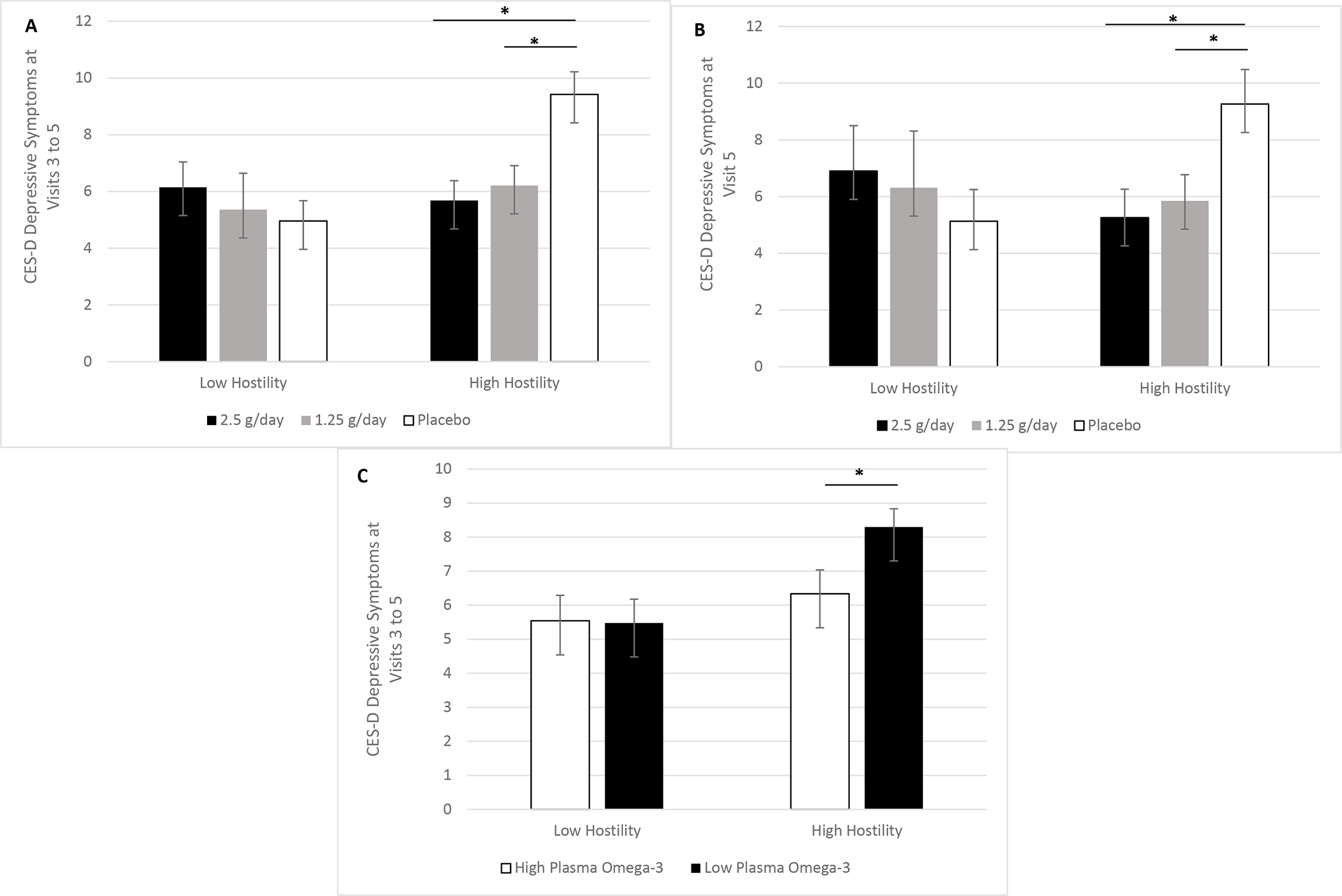

The pattern of results from the whole sample is captured Supplemental Table 1. No social stress measure moderated omega-3 fatty acids’ antidepressant effect differentially across visits (three-way interactions: ps>.10). After removing the non-significant three-way interaction term, omega-3 fatty acids’ antidepressant effect averaged across Visits 3 through 5 depended on frequency of hostile interactions (two-way interaction: χ2 (2)=7.08, p=.029). Specifically, among those at the 75th percentile of hostile interactions, both the 2.5 g/d (χ2 (1)=6.43, p=.011) and the 1.25 g/d (χ2 (1)=6.20, p=.013) omega-3 fatty acid supplementation groups had lower depressive symptoms than the placebo group; however, these between-group differences in depressive symptoms did not exist among those at the 25th percentile of hostile interactions (ps>.09). All two-way interactions with other social stress measures were non-significant (ps>.12).

Pre-planned contrasts showed that there were significant group differences at Visit 5 following the expected dose-response pattern: Among those at the 75th percentile of hostile interactions, the 2.5 g/d omega-3 supplementation tracked with lower depressive symptoms at Visit 5, compared to the placebo group (χ2 (1)=4.21, p=.040), and the 1.25 g/d supplementation group had marginally lower depressive symptoms than the placebo group (χ2 (1)=3.60, p=.058), but the two omega-3 fatty acid supplementation groups did not differ (p=.73). In contrast, there were no between-group differences in depressive symptoms at Visit 5 for those at the 25th percentile of hostile interactions (ps>.24) (Figure 1B). All other pre-planned contrasts for hostility as well as other social stress measures were non-significant (ps>.08).

Figure 1.

A-C. Omega-3 fatty acids’ relationship with depressive symptoms depended on frequency of hostile interactions. Among the overweight and obese subsample, frequency of hostile interactions moderated omega-3 fatty acid supplementation’s effect on depressive symptoms pooled across Visits 3 to 5 (p=.034). Both the 2.5 grams per day (g/d) (p=.007) and 1.25 g/d (p=.011) doses lowed depressive symptoms compared to placebo across visits among those with more frequent hostile interactions (1A). Pre-planned contrasts showed that after four months of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation, the 2.5 g/d (p=.030) and 1.25 g/d (p=.043) doses lowed depressive symptoms, compared to placebo, among those with more frequent hostile interactions (1B). Plasma omega-3 fatty acid levels corroborated these findings, in that among those with more frequent hostile interactions, higher levels of plasma omega-3 fatty acid were associated with lower depressive symptoms across visits (p=.049) (1C).

Some social stress measures were directly related to depressive symptoms. Specifically, those who reported more hostile interactions (B=1.68, SE=0.68, χ2 (1)=4.26, p=.039), insensitive interactions (B=2.14, SE=0.69, χ2 (1)=6.90, p=.009), interfering interactions (B=2.84, SE=0.95, χ2 (1)=4.37, p=.037), social tension (B=0.40, SE=0.15, χ2 (1)=6.24, p=.013), social isolation (B=0.36, SE=0.12, χ2 (1)=7.31, p=.007), and performance pressure (B=0.19, SE=0.06, χ2 (1)=7.84, p=.005) had more depressive symptoms.

Social Stress and Plasma Levels of Omega-3 Fatty Acids

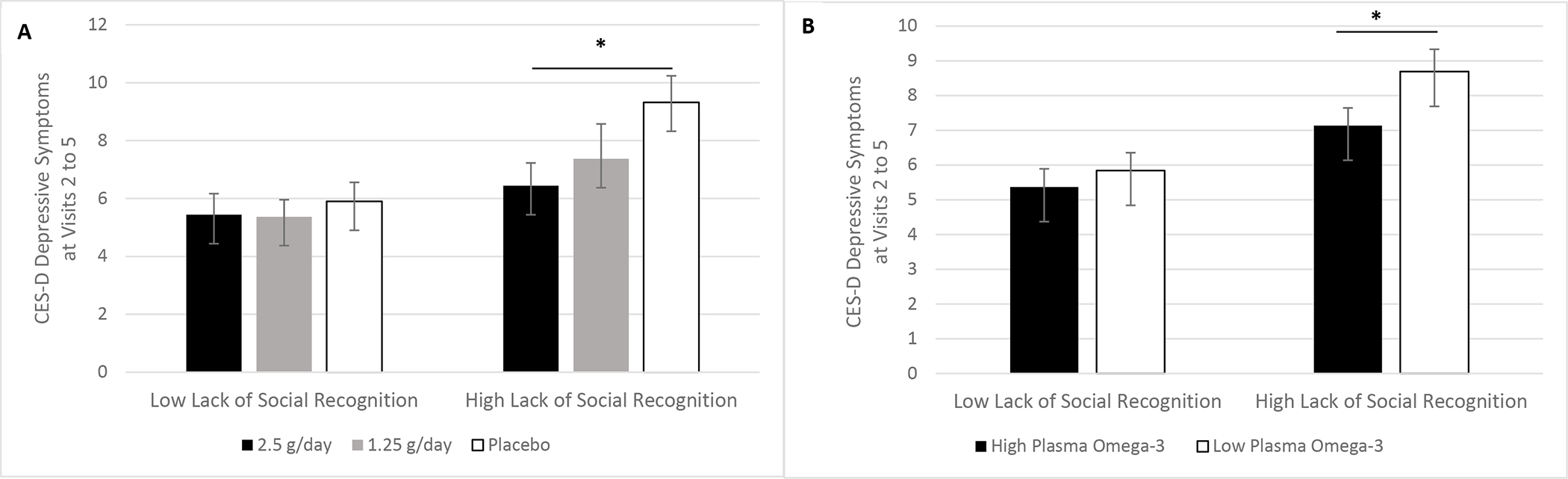

Hostility interacted with total plasma level of omega-3 fatty acids to predict depressive symptoms (χ2 (1)=4.23, p=.040), in that higher levels of plasma omega-3 fatty acids only had an antidepressant effect among those at the 75th percentile of hostile interactions (B=−0.53, SE=0.21, χ2 (1)=6.32, p=.012) but not among those at the 25th percentile of hostile interactions (p=.63). The antidepressant effect of plasma omega-3 fatty acids was not dependent on frequency of interactions characterized by insensitivity (p=.58), ridicule (p=.16), or interference (p=.58), nor by feelings of social overload (p=.38), social tension (p=.13), social isolation (p=.51), or performance pressure (p=.13). However, plasma omega-3 fatty acids’ relationship with depressive symptoms depended on lack of social recognition (χ2 (1)=5.11, p=.024). That is, higher levels of plasma omega-3 fatty acids predicted lower depressive symptoms only among those at the 75th percentile of lacking social recognition (B=−0.42, SE=0.19, χ2 (1)=5.06, p=.025) but not among those at the 25th percentile of lacking social recognition (p=.99).

Work Stress and Omega-3 Fatty Acids

The work stress subscales did not moderate omega-3 fatty acids’ antidepressant effect differentially across visits (three-way interactions: ps>.36), or pooled across visits (two-way interactions: ps>.39). All pre-planned contrasts were non-significant (ps>.08). Those who reported feeling more overloaded at work (main effect: B=0.24, SE=0.08, χ2 (1)=6.68, p=.010), more discontent with work (main effect: B=0.35, SE=0.10, χ2 (1)=9.52, p=.002), and more overextended at work (main effect: B=0.64, SE=0.15, χ2 (1)=8.91, p=.003) had more depressive symptoms. Plasma omega-3 fatty acids’ association with depressive symptoms did not depend on feelings of work discontent (p=.79), feeling overextended at work (p=.52), or feeling overloaded at work (p=.99).

Sensitivity Analyses among Overweight and Obese Participants

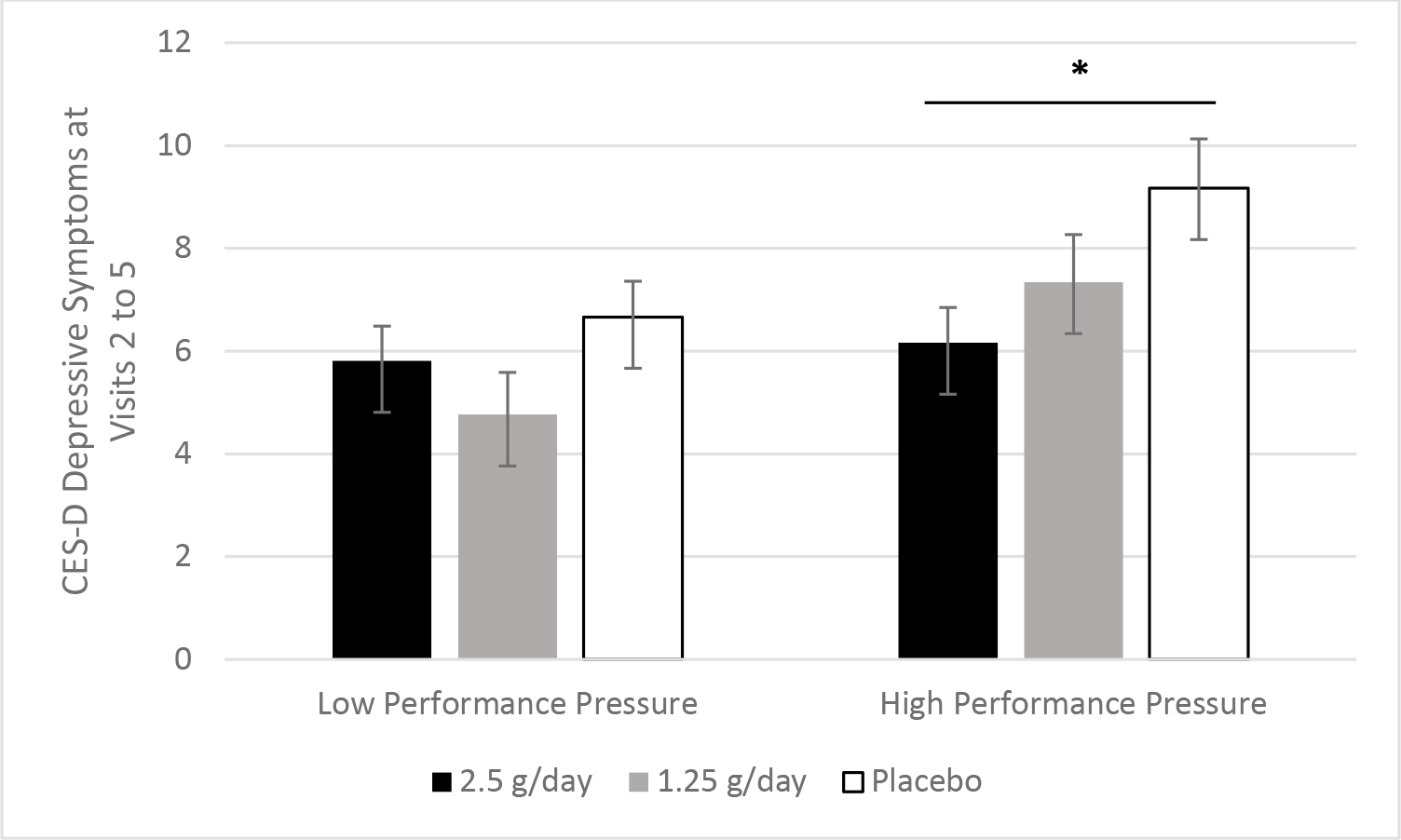

The pattern of results from the overweight subsample is depicted in Supplemental Table 2. After excluding normal weight individuals (BMI < 25 kg/m2), a similar pattern of results emerged with a few notable exceptions that tended to better support original hypotheses. The effect of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation group on depressive symptoms did not vary by any social stress measure differentially across visits (three-way interactions: ps>.06). After removing the non-significant three-way interaction term, the association between omega-3 fatty acid supplementation group and depressive symptoms depended on frequency of hostile interactions (two-way interaction: χ2 (2)=6.74, p=.034). The 2.5 g/d (χ2 (1)=7.33, p=.007) and 1.25 g/d (χ2 (1)=6.43, p=.011) doses of omega-3 fatty acids lowered depressive symptoms compared to placebo across visits among those at the 75th percentile of hostile interactions, but depressive symptoms did not differ across the two omega-3 fatty acid supplementation groups (p=.60), nor among those with less frequent hostility (ps>.25) (Figure 1A). Also, a novel finding emerged in this subsample: The association between omega-3 fatty acid supplementation group and depressive symptoms depended on performance pressure (two-way interaction: χ2 (2)=6.54, p=.038). Among those at the 75th percentile of performance pressure, the 2.5 g/d group had lower depressive symptoms across visits than the placebo group (χ2 (1)=4.83, p=.028) (Figure 2), but no other between-group contrast was significant (ps>.05). In this subsample, omega-3 fatty acid supplementation’s relationship with depressive symptoms did not depend on social isolation (p=.35), social tension (p=.08), lack of social recognition (p=.13), social overload (p=.17), nor interactions that involved interference (p=.51), ridicule (p=.63), or insensitivity (p=.15).

Figure 2.

Performance pressure moderated omega-3 fatty acid supplementation’s effect on depressive symptoms. The association between omega-3 fatty acid supplementation group and depressive symptoms depended on performance pressure among the overweight and obese subsample (p=.038). Among those who reported more frequent performance pressure, those in the 2.5 g/d group had lower depressive symptoms across visits than those in the placebo group (p=.028).

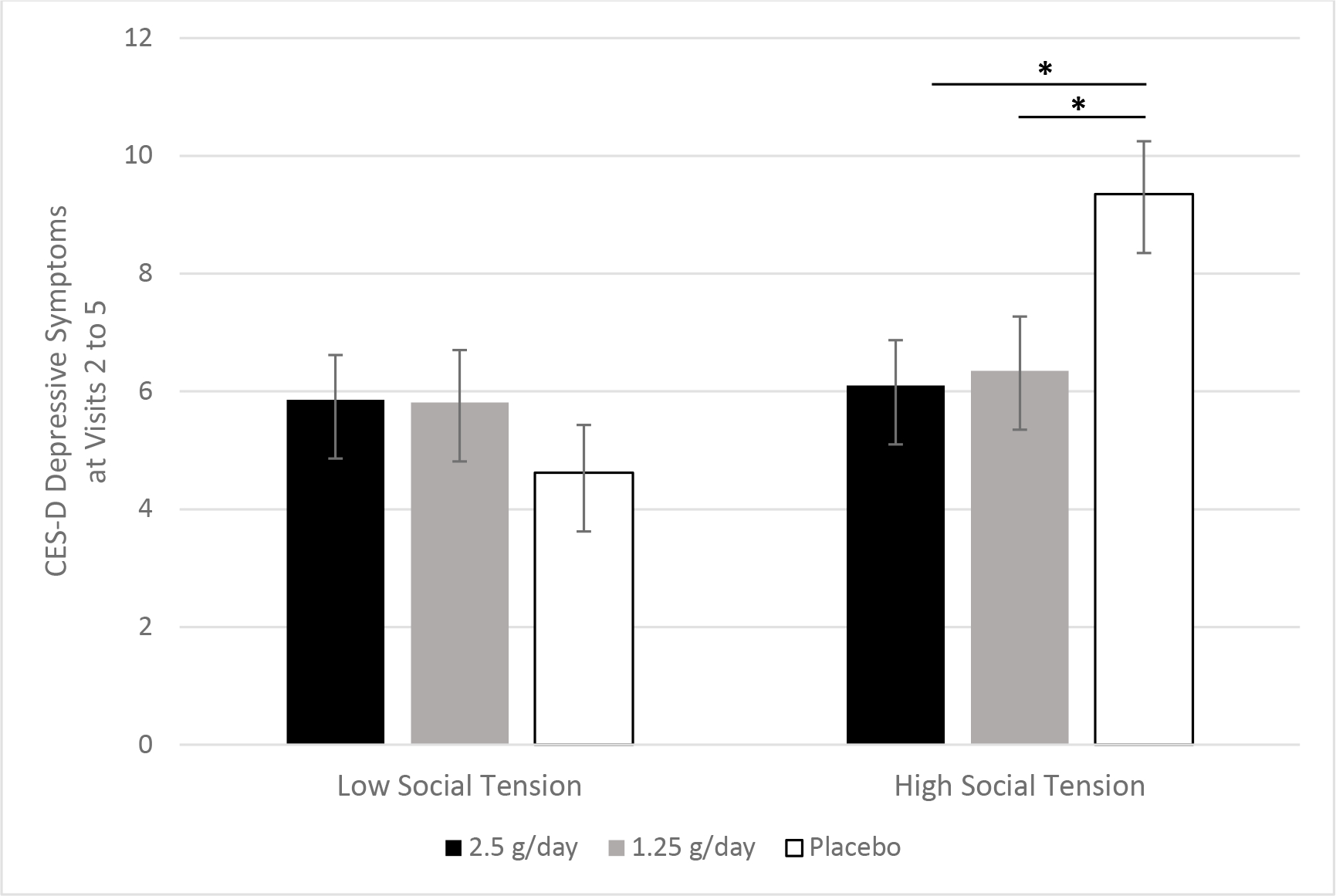

Similar to the analyses that included healthy weight individuals, pre-planned contrasts revealed that at Visit 5, the 2.5 g/d (χ2 (1)=4.74, p=.030) and 1.25 g/d (χ2 (1)=4.10, p=.043) groups had lower depressive symptoms compared to the placebo group only among those at the 75th percentile of hostile interactions (Figure 1B). The pre-planned contrasts revealed two additional unique findings in this subsample: Among overweight and obese individuals with more frequent social tension, the 2.5 g/d (χ2 (1)=5.07, p=.024) and 1.25 g/d (χ2 (1)=3.95, p=.047) doses of omega-3 fatty acid lowered depressive symptoms across visits, compared to the placebo group, but there was no difference between omega-3 fatty acid supplementation groups (p=.85), and this dose-response relationship was not evident among overweight individuals with less frequent social tension (ps>.19) (Figure 3A). Similarly, among overweight individuals at the 75th percentile of lacking social recognition, the 2.5 g/d omega-3 fatty acid group had lower depressive symptoms across visits than the placebo group (χ2 (1)=4.32, p=.038) (Figure 4A), but none of the other between-group contrasts were significant (ps>.21). Also, no other pre-planned contrasts with other stress subscales were significant (ps>.05).

Figure 3.

Omega-3 fatty acids’ association with depressive symptoms depended on social tension. Among the overweight and obese subsample, pre-planned contrasts revealed that the 2.5 g/d (p=.024) and 1.25 g/d (p=.047) doses of omega-3 fatty acids lowered depressive symptoms across visits, but only among those with more frequent social tension.

Figure 4.

A-B. Lack of social recognition moderated omega-3 fatty acids’ effect on depressive symptoms. Pre-planned contrasts among the overweight and obese subsample revealed that the 2.5 g/d omega-3 fatty acid group had lower depressive symptoms across visits than the placebo group, but only among those who more frequently lacked social recognition (p=.038) (4A). Also, the relationship between plasma omega-3 fatty acids and depressive symptoms depended on lack of social recognition (p=.019). Specifically, among those who frequently lacked social recognition, higher levels of plasma omega-3 fatty acids tracked with lower depressive symptoms (p=.016) (4B).

When looking only at overweight and obese participants, plasma omega-3 fatty acids’ relationship with depressive symptoms did not depend on social tension (p=.054), performance pressure (p=.13), social isolation (p=.36), social overload (p=.27), nor frequency of interactions involving ridicule (p=.16), interference (p=.87), or insensitivity (p=.55). However, this relationship significantly dependent on lack of social recognition (χ2 (1)=5.51, p=.019) (Figure 4B) and frequency of hostile interactions (χ2 (1)=3.87, p=.049) (Figure 1C). Among overweight individuals at the 75th percentile of lacking social recognition, higher levels of plasma omega-3 fatty acids predicted lower depressive symptoms (B=−0.50, SE=0.21, χ2 (1)=5.77, p=.016), yet this relationship was non-significant among overweight individuals at the 25th percentile of lacking social recognition (p=.81). A similar pattern emerged for frequency of hostile interactions: Only among overweight individuals at the 75th percentile of hostile interactions did higher levels of plasma omega-3 fatty acids predict lower depressive symptoms (B=−0.63, SE=0.24, χ2 (1)=6.71, p=.010), but this relationship was non-significant among overweight individuals at the 25th percentile of hostile interactions (p=.92).

Among overweight and obese participants, omega-3 fatty acid supplementation’s relationship with depressive symptoms did not depend on any work stress subscale differentially across time (three-way interactions: ps>.51) or pooled across visits (two-way interactions: ps>.18). Also, the relationship between plasma omega-3 fatty acids and depressive symptoms was not moderated by any work stress subscale (ps>.35).

Discussion

In these secondary analyses of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation among overweight and obese, sedentary, and physically healthy middle-aged adults, omega-3 fatty acids’ effect on depressive symptoms depended on participants’ levels of social stress. In line with hypotheses, this effect was unique to social stress; there was no evidence that work stress moderated the relationship between omega-3 fatty acids and depressive symptoms. Among the social stress measures, hostile interactions with close others over the past month most consistently made a difference – even among the full sample that included the healthy weight individuals. This result aligns with our prior finding that those with frequent conflict-related social stress and heightened inflammatory responsivity to a lab-based social stressor had the greatest increases in depressive symptoms over time (Madison, Andridge, et al., 2021); conversely, the current study showed that those with frequent conflict benefited the most from omega-3 fatty acids’ antidepressant effect. The observed relationships were dose-dependent, as expected, suggesting a causal relationship between omega-3 fatty acid supplementation and lower depressive symptoms, dependent on social stress levels. Notably, the findings for the supplementation groups were replicated when using plasma levels of omega-3 fatty acids. In fact, another social stress variable – lack of social recognition – moderated plasma omega-3 fatty acids’ relationship with depressive symptoms, in that higher levels of plasma omega-3 fatty acids tracked with lower depressive symptoms only among those at the 75th percentile of lacking social recognition. Results were even more pronounced when examining the overweight and obese subsample. In this subsample, there was evidence that hostile interactions, social tension, performance pressure, and lack of social recognition all moderated omega-3 fatty acids’ relationship with depressive symptoms.

In this study, work stress did not moderate omega-3 fatty acids’ relationship with depressive symptoms. These null results align with prior work showing the unique biological and psychological salience of social stress, compared to other types of stress. For example, a seminal meta-analytic finding showed that the effect of a lack of strong social relationships on mortality risk was comparable to well-known risk factors including smoking and alcohol use, and exceeded the influence of other risk factors like obesity (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010). Indeed, the Social Signal Transduction Theory of Depression focuses specifically on conflict and exclusion as powerful and reliable predictors of proinflammatory signaling and ultimately depression (Slavich & Irwin, 2014). Although there are untestable evolutionary theories as to social stress’s unique biological and psychological relevance, more work is needed to elucidate whether there are distinctive neurobiological pathways mediating social stress’s effect. Another possibility is that social stress – especially repetitive conflict with a close other – hits closer to home, literally and figuratively, than other types of stress, like a nagging boss. Ideally, the home environment is a place of rest and recovery, but an individual in a conflictual relationship may lay in bed with the source of their stress – prohibiting rest and recovery. In a hostile marriage, a potential source of support morphs into major stressor. Also, the Socioemotional Selectivity Theory posits that a bad marriage would have even greater effects in middle- and older adulthood as social networks downsize and the spouse becomes the primary source of interaction (Carstensen et al., 1999). Thus, our sample’s age demographic may play a role in our results.

The pattern of results also demonstrated that only certain types of social stress mattered for omega-3 fatty acids’ relationship with depressive symptoms. Generally speaking, social stress subscales that focused on perceived quantity of social interactions – both too many (social overload) and too few (social isolation) – did not moderate omega-3 fatty acids’ anti-depressant effect. In contrast, many of the social stress subscales that indexed quality of social interactions (i.e., hostility, tension, lack of recognition, performance pressure) helped to determine omega-3 fatty acids’ association with depressive symptoms, particularly among the overweight and obese subsample. Given this pattern of results, it is unclear why ridiculing, insensitive, and interfering interactions did not moderate omega-3 fatty acids’ antidepressant effect.

Our study paradigm and findings represent a step forward in terms of personalized, preventative medicine. Firstly, these results show that it is important to consider individual difference moderators of a treatment or preventative intervention’s effect, as failing to do so may yield an overall null effect (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2011, 2012). Secondly, our study provides insight into a potential proactive depression prevention strategy that is especially relevant in societies in which chronic inflammation and subthreshold depression is prevalent. Thirdly, because this preventative strategy targets inflammation, it may also lower risk for comorbid physical disease development. Combining prevention and treatment efforts and implementing interventions that target common etiological factors in co-occurring disorders (e.g., inflammation) are two facets of the recently proposed community-embedded model, which is designed to more adequately address widespread mental health burden (Puffer & Ayuku, 2022).

From a biological perspective, it makes sense that social stress’s modulating effect was most evident among the overweight and obese subsample. Elevated systemic inflammation and depression are more common among individuals who are overweight and obese (Milaneschi et al., 2019). Specifically, meta-analytic evidence suggests that obese individuals are 32% more likely to have depression than their normal-weight peers (Pereira-Miranda et al., 2017). Adipose tissue actively secretes proinflammatory soluble mediators (Kern et al., 2001), conducive to the development of a low mood. Therefore, it makes sense that omega-3 fatty acids’ antidepressant effect would be most notable among overweight individuals who experience frequent social stress, as they have two risk factors for elevated inflammation and depression. These findings are especially relevant in the U.S. given that current projections estimate that nearly half of U.S. adults will be obese by 2030, and that a plurality of women, non-Hispanic Black adults, and low-income individuals will be severely obese (Ward et al., 2019).

A major caveat is that these results emerged among a sample with mild depressive symptoms and low levels of social stress. Our results may be even more pronounced among a sample with a wider range of stress levels. Results should be replicated among more diverse samples, which may have higher levels of stress levels (e.g., minority stress, poverty). Indeed, our sample was primarily White and well-educated, but those with minoritized identities are more likely to suffer from chronic depressive symptoms that impair daily functioning, and healthcare providers may not readily identify due to differing symptom presentations (Bailey et al., 2019). Relatedly, it was not a clinical sample of depressed patients, so our findings do not speak to the treatment of clinical depression (e.g., major depressive disorder, persistent depressive disorder). Even so, these results have implications for prevention of depression recurrence, as 38% of the sample had a mood disorder or adjustment disorder history. Our findings are also relevant for the treatment of commonly occurring subthreshold depressive symptoms in the general population. Such symptoms are clinically important, as they predict poorer physical health and less work productivity (Beck et al., 2011; Lyness et al., 2006). In essence, results from this non-clinical sample are relevant to the general population, and omega-3 fatty acid supplementation may help to reduce widespread productivity and health loss due to mild depressive symptoms.

The current work helps to explain why we and others have failed to find a direct effect of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation on depressive symptoms (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2011, 2012). That is, omega-3 fatty acid supplementation may help to prevent depressive symptoms among those who experience frequent social stress and therefore are more at risk for inflammation-related depressive symptom increases. The current work is a corollary of the Social Signal Theory of Depression, for which we have already provided empirical support (Madison, Andridge, et al., 2021). We demonstrated that individuals who have greater inflammatory reactivity to a lab-based social stressor as well as more frequent social stress, but not other kinds of stress, report greater depressive symptom increases over time (Madison et al., 2021). These findings parallel other results from our lab which showed that people who had frequent social stress, but not other types of stress, were more sensitive to the mood and pain effects of mild inflammatory increases (Madison et al., in press). We also have demonstrated that four months of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation can reduce inflammatory reactivity to acute social stress (Madison, Belury, et al., 2021). In this study, we close the loop, showing that omega-3 fatty acids’ antidepressant effect is evident among those who have more frequent social stress. In short, those who are more psychologically vulnerable to the effects of inflammation (i.e., the socially-stressed) may experience a greater anti-depressant effect of omega-3 as it mutes their inflammatory responses.

This work suggests that for those in the general population with frequent social stress, omega-3 fatty acid supplementation may help to ward off depression symptom increases, perhaps by lowering inflammatory responses to stress (Madison, Belury, et al., 2021). This focus is advantageous because stress is inevitable, and omega-3 supplementation simply targets the cellular response to stress. According to the Social Signal Transduction Theory, it may also be fruitful to target stress exposure frequency. Specifically, among those who experience frequent social stress, such as a hostile marriage, addressing the stress directly (e.g., via communication or conflict resolution skills, marriage therapy, or separation/divorce) may be a necessary step in treating or preventing depression. Indeed, from a clinical standpoint, it is unhelpful, undermining, and even negligent to recommend an anti-inflammatory dietary supplement as a depression prevention strategy for someone in an abusive relationship, for example. Nevertheless, these findings show how an anti-inflammatory dietary supplement can help to buffer the mental health impact of commonplace social stress, which at times may be unavoidable.

Strengths and Limitations

Besides the demographic features of our sample discussed above, other important features of our sample include that they were sedentary, overweight, and middle-aged. These factors likely accentuated our results, and our findings may not replicate among a more active, healthy weight, and younger sample. Also, our stress measures relied on self-report data – another limitation due to the biases inherent in self-report. One idea for future work would be to observe a social interaction (e.g., a marital conflict) at the screening visit, code behavior (e.g., hostility), and then engage in a stratified randomization strategy whereby participants with high and low levels of hostility are randomized to supplementation groups or placebo. It is also worth mentioning that the TICS and TENSE were administered at different visits, and this along with our limited statistical power precluded head-to-head comparison. Another limitation of this work is that, as an exploratory study, there were many statistical tests and we tested a greater number of social stress subscales than work stress subscales. Our significant results would not survive even the least conservative multiple test correction. That said, our a priori hypotheses focused on conflict-related social stress; because it was an exploratory study, we tested non-social stress as a comparison, but we did not expect to find effects. Although results need to be replicated before informing clinical practice, our pattern of results is notable given that it aligned with our theory-driven hypotheses as well as our prior results showing that conflict-related social stress can uniquely sensitize people to inflammation’s psychological effects (Madison, Andridge, et al., 2021; Madison et al., in press).

Strengths of our study include the three-arm, randomized, placebo-controlled design that tested two different doses of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation. Also, we measured plasma levels of omega-3 fatty acids to bolster evidence that increases in circulating omega-3 fatty acid levels were the mechanism of action. We largely replicated our results when substituting plasma levels of omega-3 fatty acids for supplementation group.

Supplementary Material

Significance:

Omega-3 supplementation can lower inflammation, and inflammation is implicated in the etiology of some cases of depression, so it is unclear why meta-analytic evidence does not support an anti-depressant benefit of omega-3. Here, in a non-clinical sample, we showed that omega-3 reduced depressive symptoms among people who had more frequent social stress, and especially conflict. This effect was specific to social stress, and these results show the importance of looking at how individual differences impact a treatment or preventative strategy’s effect – in line with personalized medicine.

Clinical Implications.

One-third to one-half of depressed people have elevated inflammation (Raison & Miller, 2011; Rethorst et al., 2014). The relationship is bidirectional (Mac Giollabhui et al., 2020), promoting a vicious cycle of poor mental and physical health. This phenomenon helps to explain why depression commonly co-occurs with inflammatory diseases (Marrie et al., 2017) and why one-third to one-half of depression cases are resistant to traditional antidepressant treatments, which do not specifically target inflammation (e.g., SSRIs) (Nemeroff, 2007). The current study tests a safe, low-cost anti-inflammatory dietary supplement – omega-3 fatty acids – which may help to prevent the onset of inflammation-associated, difficult-to-treat cases of depression.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by NIH grants AG029562, AG038621, and UL1RR025755. OmegaBrite (Waltham, MA) supplied the omega-3 fatty acid supplement and placebo without charge and without restrictions; OmegaBrite did not influence the design, funding, implementation, interpretation, or publication of the data.

Footnotes

All authors report no conflicts of interest.

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00385723

References

- Appleton KM, Voyias PD, Sallis HM, Dawson S, Ness AR, Churchill R, & Perry R (2021). Omega-3 fatty acids for depression in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey RK, Mokonogho J, & Kumar A (2019). Racial and ethnic differences in depression: Current perspectives. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 603–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballinger GA (2004). Using generalized estimating equations for longitudinal data analysis. Organizational Research Methods, 7(2), 127–150. [Google Scholar]

- Beck A, Crain AL, Solberg LI, Unützer J, Glasgow RE, Maciosek MV, & Whitebird R (2011). Severity of depression and magnitude of productivity loss. The Annals of Family Medicine, 9(4), 305–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belury MA, & Kempa-Steczko A (1997). Conjugated linoleic acid modulates hepatic lipid composition in mice. Lipids, 32(2), 199–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bligh EG, & Dyer WJ (1959). A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Canadian Journal of Biochemistry and Physiology, 37(8), 911–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonafede MM, Gandra SR, Watson C, Princic N, & Fox KM (2012). Cost per treated patient for etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximab across adult indications: A claims analysis. Advances in Therapy, 29(3), 234–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Isaacowitz DM, & Charles ST (1999). Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist, 54(3), Article 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cave C, Hein N, Smith LM, Anderson-Berry A, Richter CK, Bisselou KS, Appiah AK, Kris-Etherton P, Skulas-Ray AC, & Thompson M (2020). Omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids intake by ethnicity, income, and education level in the United States: NHANES 2003–2014. Nutrients, 12(7), 2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, Smit F, & Van Straten A (2007). Psychological treatments of subthreshold depression: A meta-analytic review. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 115(6), 434–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Perez MA, & Nunez-Anton V (2003). Cellwise residual analysis in two-way contingency tables. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 63(5), 825–839. [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, & Layton JB (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern PA, Ranganathan S, Li C, Wood L, & Ranganathan G (2001). Adipose tissue tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6 expression in human obesity and insulin resistance. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Belury MA, Andridge R, Malarkey WB, & Glaser R (2011). Omega-3 supplementation lowers inflammation and anxiety in medical students: A randomized controlled trial. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 25(8), Article 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Belury MA, Andridge R, Malarkey WB, Hwang BS, & Glaser R (2012). Omega-3 supplementation lowers inflammation in healthy middle-aged and older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 26(6), 988–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Epel ES, Belury MA, Andridge R, Lin J, Glaser R, Malarkey WB, Hwang BS, & Blackburn E (2013). Omega-3 fatty acids, oxidative stress, and leukocyte telomere length: A randomized controlled trial. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 28, 16–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y, Xie B, Zhang H, He Q, Guo L, Subramaniapillai M, Fan B, Lu C, & Mclntyer R (2019). Efficacy of omega-3 PUFAs in depression: A meta-analysis. Translational Psychiatry, 9(1), 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyness JM, Heo M, Datto CJ, Ten Have TR, Katz IR, Drayer R, Reynolds III CF, Alexopoulos GS, & Bruce ML. (2006). Outcomes of minor and subsyndromal depression among elderly patients in primary care settings. Annals of Internal Medicine, 144(7), 496–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mac Giollabhui N, Ng TH, Ellman LM, & Alloy LB (2020). The longitudinal associations of inflammatory biomarkers and depression revisited: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Molecular Psychiatry, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madison AA, Andridge R, Shrout MR, Renna ME, Bennett JM, Jaremka LM, Fagundes CP, Belury MA, Malarkey WB, & Kiecolt-Glaser JK (2021). Frequent interpersonal stress and inflammatory reactivity predict depressive symptom increases: Two tests of the social signal transduction theory of depression. Psychological Science, 33(1), 152–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madison AA, Belury MA, Andridge R, Renna ME, Shrout MR, Malarkey WB, Lin J, Epel ES, & Kiecolt-Glaser JK (2021). Omega-3 supplementation and stress reactivity of cellular aging biomarkers: An ancillary substudy of a randomized, controlled trial in midlife adults. Molecular Psychiatry, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madison AA, Renna ME, Andridge R, Peng J, Sheridan J, Lustberg M, Ramaswamy B, Wesolowski R, VanDeusen JB, Williams NO, Sardesai SD, Noonan A, Reinbolt RE, Stover D, Cherian M, Malarkey WB, & Kiecolt-Glaser J (in press). Conflicts hurt: Social stress predicts elevated pain and sadness following mild inflammatory increases. Pain. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrie RA, Walld R, Bolton JM, Sareen J, Walker JR, Patten SB, Singer A, Lix LM, Hitchon CA, & El-Gabalawy R (2017). Increased incidence of psychiatric disorders in immune-mediated inflammatory disease. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 101, 17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsland AL, Walsh C, Lockwood K, & John-Henderson NA (2017). The effects of acute psychological stress on circulating and stimulated inflammatory markers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 64, 208–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milaneschi Y, Simmons WK, van Rossum EF, & Penninx BW (2019). Depression and obesity: Evidence of shared biological mechanisms. Molecular Psychiatry, 24(1), 18–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mocking R, Harmsen I, Assies J, Koeter M, Ruhé H, & Schene A (2016). Meta-analysis and meta-regression of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation for major depressive disorder. Translational Psychiatry, 6(3), e756–e756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemeroff CB (2007). Prevalence and management of treatment-resistant depression. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 68(8), 17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong KL, Allison MA, Cheung BM, Wu BJ, Barter PJ, & Rye K-A (2013). Trends in C-reactive protein levels in US adults from 1999 to 2010. American Journal of Epidemiology, 177(12), 1430–1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papanikolaou Y, Brooks J, Reider C, & Fulgoni VL (2014). US adults are not meeting recommended levels for fish and omega-3 fatty acid intake: Results of an analysis using observational data from NHANES 2003–2008. Nutrition Journal, 13(1), 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pariante CM (2021). Increased Inflammation in Depression: A Little in All, or a Lot in a Few? American Journal of Psychiatry, 178(12), 1077–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira-Miranda E, Costa PR, Queiroz VA, Pereira-Santos M, & Santana ML (2017). Overweight and obesity associated with higher depression prevalence in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 36(3), 223–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puffer ES, & Ayuku D (2022). A Community-Embedded Implementation Model for Mental-Health Interventions: Reaching the Hardest to Reach. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 17456916211049362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Raison CL, & Miller AH (2011). Is depression an inflammatory disorder? Current Psychiatry Reports, 13(6), 467–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raison CL, Rutherford RE, Woolwine BJ, Shuo C, Schettler P, Drake DF, Haroon E, & Miller AH (2013). A randomized controlled trial of the tumor necrosis factor antagonist infliximab for treatment-resistant depression: The role of baseline inflammatory biomarkers. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(1), Article 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rethorst CD, Bernstein I, & Trivedi MH (2014). Inflammation, obesity and metabolic syndrome in depression: Analysis of the 2009–2010 National Health and Nutrition Survey (NHANES). The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 75(12), e1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruehlman LS, & Karoly P (1991). With a little flak from my friends: Development and preliminary validation of the Test of Negative Social Exchange (TENSE). Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 3(1), 97. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Villegas A, Martínez-González MA, Estruch R, Salas-Salvadó J, Corella D, Covas MI, Arós F, Romaguera D, Gómez-Gracia E, & Lapetra J (2013). Mediterranean dietary pattern and depression: The PREDIMED randomized trial. BMC Medicine, 11(1), 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz P, & Schlotz W (2002). Das Trierer Inventar zur Erfassung von chronischem Stress—Version 2 (TICS 2). Trierer Psychologische Berichte, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Shafiei F, Salari-Moghaddam A, Larijani B, & Esmaillzadeh A (2019). Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and risk of depression: A systematic review and updated meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutrition Reviews, 77(4), 230–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shantha NC, Decker EA, & Hennig B (1993). Comparison of methylation methods for the quantitation of conjugated linoleic acid isomers. Journal of AOAC International, 76(3), 644–649. [Google Scholar]

- Slavich GM, & Irwin MR (2014). From stress to inflammation and major depressive disorder: A social signal transduction theory of depression. Psychological Bulletin, 140(3), Article 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannice G, & Rasmussen H (2014). Position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics: Dietary fatty acids for healthy adults. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 114(1), 136–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward ZJ, Bleich SN, Cradock AL, Barrett JL, Giles CM, Flax C, Long MW, & Gortmaker SL (2019). Projected US state-level prevalence of adult obesity and severe obesity. New England Journal of Medicine, 381(25), 2440–2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Sholomskas D, Pottenger M, Prusoff BA, & Locke BZ (1977). Assessing depressive symptoms in five psychiatric populations: A validation study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 106(3), 203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeger SL, & Liang K-Y (1986). Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics, 121–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.