Abstract

Introduction:

SeLECTS is a transient developmental epilepsy with a seizure onset zone localized to the centrotemporal cortex that commonly impacts aspects of language function. To better understand the relationship between these anatomical findings and symptoms, we characterized the language profile and white matter microstructural and macrostructural features in a cohort of children with SeLECTS.

Methods:

Children with active SeLECTS (n=13), resolved SeLECTS (n=12), and controls (n=17) underwent high-resolution MRIs including diffusion tensor imaging sequences and multiple standardized neuropsychological measures of language function. We identified the superficial white matter abutting inferior rolandic cortex and superior temporal gyrus using a cortical parcellation atlas and derived the arcuate fasciculus connecting them using probabilistic tractography. We compared white matter microstructural characteristics (axial, radial and mean diffusivity, and fractional anisotropy) between groups in each region, and tested for linear relationships between diffusivity metrics in these regions and language scores on neuropsychological testing.

Results:

We found significant differences in several language modalities in children with SeLECTS compared to controls. Children with SeLECTS performed worse on assessments of phonological awareness (p=0.045) and verbal comprehension (p=0.050). Reduced performance was more pronounced in children with active SeLECTS compared to controls, namely, phonological awareness (p=0.028), verbal comprehension (p=0.028), and verbal category fluency (p=0.031), with trends toward worse performance also observed in verbal letter fluency (p=0.052), and the expressive one-word picture vocabulary test (p=0.068). Children with active SeLECTS perform worse than children with SeLECTS in remission on tests of verbal category fluency (p=0.009), verbal letter fluency (p=0.006), and the expressive one-word picture vocabulary test (p=0.045). We also found abnormal superficial white matter microstructure in centrotemporal ROIs in children with SeLECTS, characterized by increased diffusivity and fractional anisotropy compared to controls (AD p=0.014, RD p=0.028, MD p=0.020, and FA p=0.024). Structural connectivity of the arcuate fasciculus connecting perisylvian cortical regions was lower in children with SeLECTS (p=0.045), and in the arcuate fasciculus children with SeLECTS had increased diffusivity (AD p=0.007, RD p=0.006, MD p=0.016), with no difference in fractional anisotropy (p=0.22). However, linear tests comparing white matter microstructure in areas constituting language networks and language performance did not withstand correction for multiple comparisons in this sample, although a trend was seen between FA in the arcuate fasciculus and verbal category fluency (p=0.047) and the expressive one-word picture vocabulary test (p=0.036).

Conclusion:

We found impaired language development in children with SeLECTS, particularly in those with active SeLECTS, as well as abnormalities in the superficial centrotemporal white matter as well as the fibers connecting these regions, the arcuate fasciculus. Although relationships between language performance and white matter abnormalities did not pass correction for multiple comparisons, taken together, these results provide evidence of atypical white matter maturation in fibers involved in language processing, which may contribute to the aspects of language function that are commonly affected with the disorder.

Keywords: Rolandic epilepsy, self-limited epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes, speech, language, DTI, tractography

Introduction

Self-limited epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (SeLECTS, previously referred to as benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes, BECTS), is a common, developmental epilepsy syndrome representing 10–15% of childhood epilepsies [1–4]. The disease is characterized by self-limited focal seizures arising from the inferior rolandic cortex [5], typically consisting of unilateral facial sensorimotor symptoms, speech arrest, oropharyngolaryngeal manifestations, and hypersalivation. Concordant with epilepsy, children often exhibit neurocognitive (language, motor, and attentional) comorbidities [6–12]. The active phase of epilepsy occurs during school-age and early teenage years [13], during which time the brain undergoes a complex, nonlinear process of white matter maturation [14–18], wherein disproportionate rates of myelination across the brain change the network of structural connectivity [19].

Aberrant white matter maturation has been linked to neuropsychological impact and/or impairment in focal and generalized epilepsy [10, 20]. Children with SeLECTS have abnormalities in white matter microstructure near the rolandic cortex [10, 21, 22], where superficial white matter abnormalities abutting the rolandic cortex correlate with fine motor impairment [23]. However, as the name implies, children with SeLECTS typically exhibit abnormal electrophysiology spanning beyond the rolandic (“central”) frontal region, also involving the adjacent temporal region [24, 25]. These perisylvian frontal and temporal regions overlap with cortical nodes critical for language function.

Given the language dysfunction reported and the electrophysiologic evidence of perisylvian rolandic and temporal involvement, we hypothesized that children with SeLECTS would have: 1) microstructural differences in the superficial white matter adjacent to the inferior rolandic and superior temporal cortical regions and 2) macrostructural differences in the white matter structural connectivity between these regions.

We further characterized the language challenges classically observed in children with SeLECTS and explored whether these abnormalities correlate with white matter structural features. Identification of a relationship between structural language network anomalies and performance on standardized measures of language functioning in SeLECTS would shed light on the cause and resolution of cognitive symptoms in this common developmental epilepsy.

Methods

Subjects

Selection criteria for this study included children ages 4–16 years old who received a clinical diagnosis of SeLECTS by a child neurologist following ILAE criteria, including both a history of focal motor or generalized seizure and an EEG showing sleep-activated centrotemporal spikes [5]. Subjects with a history of only a single clinical seizure were included (n=2) if clinical and EEG features led to the diagnosis of SeLECTS [26]. Age-matched healthy control subjects without a history of seizure or known neurological or psychiatric disorder were also recruited. Exclusion criteria for both children with SeLECTS and healthy control subjects included a history of abnormal neuroimaging, autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, or other unrelated neurological disease. SeLECTS subjects with attention disorders and mild learning difficulties were included, as these profiles are consistent with known SeLECTS comorbidities [27].

26 children with SeLECTS and 21 healthy control children were recruited. Children with SeLECTS were categorized as having active epilepsy if they had had a seizure within the previous 12 months or as being in remission if they had been seizure free for at least 12 months, based on the natural history of resolution in this disease [13]. For imaging analysis, 4 subjects were unable to tolerate the MRI and all 5 left-handed subjects were excluded as a conservative measure of control for hemispheric language lateralization given an elevated possibility of mixed (or reverse) dominance, leaving 20 right-handed SeLECTS subjects (16M, mean age ± standard deviation SD 11.36 ± 1.68 years), 13 with active SeLECTS (10M, age 10.66 ± 1.46 years) and 7 in remission (6M, age 12.66 ± 1.28 years), and 18 controls (10M, age 10.76 ± 2.55 years) with MRI data. All children were fluent speakers of English who receive formal education in English; 2 children were bilingual with Portuguese as their heritage language. For language characterization, 25 children with SeLECTS (20M, age 11.51 ± 1.88 years), including 13 active (10M, age 10.85 ± 1.64 years) and 12 remission (10M, age 12.23 ± 1.92 years); and 17 controls (9M, age 11.11 ± 2.41 years) completed neuropsychological testing. For comparison between neuropsychological and MRI measures, data were collected from 19 right-handed SeLECTS subjects (15M, age 11.38 ± 1.72 years) and 14 right-handed healthy controls (7M, age 10.84 ± 2.49 years) had both MRI and neuropsychological data available. Medication status, date of first seizure and most recent seizure were recorded at the time of the study visit. Subject characteristics are listed in Table 1. Pediatric subjects and their guardians gave age-appropriate informed consent, and this study was approved by the institutional review board at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics

| ID | Group | Preferred language | Sex | Age at scan (years) | Age at diagnosis (years) | Duration seizure free (mo) | DDisease dstatus | ACDs at scan | Dominant Hand | Language evaluation and MRI | Comorbid neuropsychological ddiagnoses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| 1 | SeLECTS | English | F | 9.1 | 8.2 | 1 | Active | LEV, LTG | Right | Both | ADHD, language + auditory processing LDs |

| 2 | SeLECTS | Bilingual: English (school) and Portuguese (heritage) |

F | 10.6 | 6.5 | 5 | Active | LEV | Right | Both | Language-based LD |

| 3 | SeLECTS | Bilingual: English (school) and Portuguese (heritage) |

F | 11 | 8.7 | 2 | Active | No | Right | Both | None |

| 4 | SeLECTS | English | F | 12.9 | 7.8 | 35 | Remission | No | Right | Language | ADHD |

| 5 | SeLECTS | English | F | 13.7 | 6.7 | 51 | Remission | No | Right | MRI | ADHD |

| 6 | SeLECTS | English | M | 8 | 5.3 | 29 | Remission | No | Right | Language | None |

| 7 | SeLECTS | English | M | 9.1 | 8.3 | 0 | Active | No | Right | Both | ADHD |

| 8 | SeLECTS | English | M | 9.6 | 9 | 7 | Active | No | Right | Both | ADHD, Dyslexia |

| 9 | SeLECTS | English | M | 9.8 | 9.7 | 0 | Active | OXC | Right | Both | None |

| 10 | SeLECTS | English | M | 9.9 | 7.7 | 5 | Active | No | Right | MRI | None |

| 11 | SeLECTS | English | M | 10.1 | 9.6 | 6 | Active | No | Right | Both | ADHD |

| 12 | SeLECTS | English | M | 10.3 | 7.9 | 25 | Remission | LEV | Right | Language | LDs in speech and reading |

| 13 | SeLECTS | English | M | 10.9 | 8.3 | 10 | Active | No | Right | MRI | None |

| 14 | SeLECTS | English | M | 10.9 | 8.9 | 0 | Active | LTG, LEV | Right | MRI | None |

| 15 | SeLECTS | English | M | 11.3 | 10.8 | 1 | Active | No | Right | MRI | ADHD, LDs in written expression and mathematics |

| 16 | SeLECTS | English | M | 11.5 | 9.7 | 20 | Remission | No | Right | Both | None |

| 17 | SeLECTS | English | M | 11.6 | 10.8 | 3 | Active | LEV | Right | MRI | None |

| 18 | SeLECTS | English | M | 11.6 | 10.4 | 14 | Remission | No | Right | MRI | None |

| 19 | SeLECTS | English | M | 11.8 | 10.1 | 17 | Remission | LEV | Right | Both | None |

| 20 | SeLECTS | English | M | 11.9 | 7.4 | 24 | Remission | LEV | Right | Both | None |

| 21 | SeLECTS | English | M | 12 | 6.7 | 42 | Remission | No | Right | Language | None |

| 22 | SeLECTS | English | M | 13.3 | 9 | 26 | Remission | LEV | Right | Both | None |

| 23 | SeLECTS | English | M | 13.4 | 12.5 | 0 | Active | LCS | Left | Language | None |

| 24 | SeLECTS | English | M | 14.7 | 10.4 | 1 | Active | No | Right | Both | Dyspraxia |

| 25 | SeLECTS | English | M | 14.8 | 7.9 | 40 | Remission | No | Right | Both | None |

| 26 | SeLECTS | English | M | 14.9 | 5.9 | 38 | Remission | No | Left | Language | ADHD, LD in mathematics |

| 27 | Control | English | F | 7.2 | . | . | . | . | Right | Both | None |

| 28 | Control | English | F | 9 | . | . | . | . | Right | Both | None |

| 29 | Control | English | F | 9.4 | . | . | . | . | Right | Both | None |

| 30 | Control | English | F | 9.4 | . | . | . | . | Right | MRI | None |

| 31 | Control | English | F | 12.2 | . | . | . | . | Left | Language | None |

| 32 | Control | English | F | 12.9 | . | . | . | . | Right | Both | None |

| 33 | Control | English | F | 13.4 | . | . | . | . | Right | Both | None |

| 34 | Control | English | F | 14.2 | . | . | . | . | Right | Both | None |

| 35 | Control | English | F | 14.3 | . | . | . | . | Right | Both | None |

| 36 | Control | English | M | 7.4 | . | . | . | . | Right | Both | None |

| 37 | Control | English | M | 8 | . | . | . | . | Right | MRI | None |

| 38 | Control | English | M | 8.3 | . | . | . | . | Right | Both | None |

| 39 | Control | English | M | 8.7 | . | . | . | . | Right | Both | None |

| 40 | Control | English | M | 9.4 | . | . | . | . | Right | MRI | None |

| 41 | Control | English | M | 10.7 | . | . | . | . | Left | Language | None |

| 42 | Control | English | M | 10.9 | . | . | . | . | Right | Both | None |

| 43 | Control | English | M | 11.5 | . | . | . | . | Right | Both | None |

| 44 | Control | English | M | 11.8 | . | . | . | . | Right | Both | None |

| 45 | Control | English | M | 12.7 | . | . | . | . | Right | Both | None |

| 46 | Control | English | M | 14.3 | . | . | . | . | Left | Language | None |

| 47 | Control | English | M | 15.1 | . | . | . | . | Right | MRI | None |

ACD, anticonvulsant drug; LCS, Lacosamide; LD, learning disorder; LEV, Levetiracetam; LTG, Lamotrigine; OXC, Oxcarbazepine. Duration seizure free is calculated from date of MRI unless no MRI, in which case from date of language evaluation.

Data acquisition

Magnetic resonance imaging

High-resolution MRI data were acquired on a 3T Magnetom Prisma scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) using a 64-channel head coil with the following sequences: DTI (64 diffusion-encoding directions, TE = 82 ms, TR = 8080 ms, flip angle = 90°, voxel size = 2.0 × 2.0 × 2.0 mm, diffusion sensitivity of b = 2000 s/mm2, number of slices = 74, skip 0), MPRAGE (TE = 1.74 ms, TR = 2530 ms, flip angle = 7°, voxel size = 1 × 1 × 1 mm) and multi-echo FLASH (TE = 1.85, 3.85, 5.85, 7.85, 9.85, 11.85, 13.85, 15.85 ms, TR = 2000 ms, flip angle = 5°, voxel size = 1 × 1 × 1 mm). FSL’s FMRIB software library was used to correct for eddy current distortion, field inhomogeneities, and head motion. A diffusion tensor model was computed at each voxel using FSL-DTIFIT, from which four measures, axial, radial, and mean diffusivity (AD, RD, and MD), and fractional anisotropy (FA), were computed. Multiecho Flash MPRAGE data were co-registered to the DTI data using an affine transformation matrix generated by FreeSurfer’s bbregister tool for each subject [28].

ROI Selection

To obtain subject-specific volumetric masks corresponding to superficial white matter underlying cortical language areas, regions of interest were first defined on cortical surfaces. Pre- and postcentral gyri cortical surfaces were labeled in structural MRI space using FreeSurfer’s Desikan-Killiany gyral-based atlas [29]. We used a customized MATLAB procedure to then isolate the inferior half of both rolandic gyral surfaces to isolate the perisylvian rolandic regions near the face and mouth representation areas, most involved in SeLECTS seizure semiology [30] and implicated in expressive language functions [31]. To do so, in each subject, the distance between the most superior and inferior vertices in the surfaces along the coronal plane was calculated. We then created a spherical cortical label with the center focused on the inferior vertex and the radius set to half of the calculated distance between inferior and superior maxima. The final inferior perirolandic cortical label was defined as all overlapping voxels between the constructed sphere and the extracted pre- and postcentral gyri cortical surfaces. All labels were then visually inspected to confirm the label consistently extended from sylvian fissure to the omega sign in perirolandic cortex, indicating that the entire peri-oral homunculus was included. The superior temporal gyrus cortical surface, selected due to functional relevance for receptive language functions [31], was labeled using the Destrieux cortical parcellation atlas [32].

For the perisylvian white matter label, the rolandic and superior temporal cortical labels were projected radially inward to create a volume consistently capturing the superficial white matter space extending from 1 mm radially to 1.5 mm radially, rendering a 0.5 mm thick planar volumetric mask for each subject (Figure 1). We chose this thin planar geometry for three reasons: 1) to maximize the capture of white matter immediately adjacent to our cortical structures of interest; 2) to minimize the chance of including superficial voxels overlapping with gray matter; and 3) to minimize capture of deeper voxels overlapping with white matter fibers primarily descending to the corona radiata. Volumetric masks were then transformed from structural MRI space into diffusion space using an intrasubject co-registration matrix. As the diffusion space was generated using lower resolution 2.0 × 2.0 × 2.0 mm voxels, to maintain the specificity of the label to voxels containing majority superficial white matter, we included only those voxels with greater than 70 percent overlap with the initial label in our final ROIs.

Figure 1: Centrotemporal ROI selection process.

(A) Inferior pre- and postcentral (perirolandic, purple) [superior temporal gyrus (green)] cortical surfaces were labelled in structural MRI space using FreeSurfer’s Desikan-Killiany [Destrieux] gyral-based atlas. (B) The same labels shown on the surface of the white matter (blue). (C, D) The labels (blue) are shown in coronal and sagittal views of a structural MRI. (D, E) To transform the labels to capture superficial white matter in diffusion space, the labels were first projected radially into the white matter extending from to 1 to 1.5 mm radially. After co-registration with diffusion space, voxels with ≥70% overlap with the label were included in the final ROI, shown here on fractional anisotropy maps in diffusion space.

To explore superficial white matter microstructure outside of the perisylvian language regions, we defined cortical labels of each lobe (frontal, parietal, occipital, and temporal) in structural MRI space using FreeSurfer’s Desikan-Killiany gyral-based atlas. We chose these labels to exclude gyri included in our perisylvian label, such that the precentral gyrus was not included in the frontal lobe, the postcentral gyrus was not included in the parietal lobe, and the superior temporal gyrus was not included in the temporal lobe (Figure 2). Following the same methodology as in perisylvian language regions, lobar cortical labels were projected 1 mm and 1.5 mm into white matter space and the corresponding 0.5 mm thick regions were used as planar volumetric masks. These masks were transformed into diffusion space using the intra-subject structural-to-diffusion co-registration matrix.

Figure 2: Control ROIs.

Control ROIs not involved in the centrotemporal perisylvian region are shown on this example cortical surface.

To investigate deep white matter microstructural features, as in our previous study [23], whole-brain white matter masks and lobar white matter masks were generated using FreeSurfer’s Desikan-Killiany white matter volumetric atlas [29]. The masks were transformed into diffusion space using a co-registration matrix following equivalent procedures as above.

White matter microstructure

For each superficial white matter ROI, values of the four DTI metrics, axial diffusivity (AD), radial diffusivity (RD), mean diffusivity (MD), and fractional anisotropy (FA), were extracted from each voxel using FSL-FMRIB’s Diffusion Toolbox [33], and then averaged across all voxels per ROI. To characterize white matter microstructure within our inferred white matter tracks using tractography, the four DTI metrics were extracted from each voxel through which any streamline passed, and an average was calculated for each DTI value in the tract volume weighted by the proportion of streamlines that passed through that voxel.

Tractography

To derive the arcuate fasciculus, the perirolandic (e.g. inferior rolandic and superior temporal gyri) cortical surfaces were used as seed and target regions for quantitative white matter connectivity analysis [34, 35] using ball-and-stick model based probabilistic diffusion tensor tracking (Probtrackx2 through FSL 5.0.4/FDT — FMRIB’s Diffusion Toolbox 3.0; FMRIB’s Software Library; Figure 3) [36]. BEDPOSTx (Bayesian Estimation of Diffusion Parameters Obtained using Sampling Techniques for modelling Crossing Fibres) was used to estimate the principal diffusion direction per voxel [33]. Probtrackx2 was then used to repeatedly sample from the distributions within an ROI, each time computing a streamline (inferred fiber tract) with the following specifications: 5000 streamlines per ROI voxel sampled, 0.2 cosine curvature threshold, thereby allowing an angle of curvature less than or equal to about 80 degrees between each voxel, distance correction applied to weight longer-reaching streamlines more heavily, loop checks performed to prevent streamlines from looping back on themselves, and a subsidiary fiber volume threshold of 0.01 of the parent fiber volume to exclude negligible volumes. A termination mask equal to the target ROI was applied to immediately terminate tracts that entered the target ROI, such that individual streamlines that entered, exited, and re-entered the target ROI were counted only once. To compute bidirectional connectivity between the two cortical labels, the inferior rolandic gyrus was first used as a seed and the superior temporal gyrus first used a target, and then the seed and target classifications switched, and the process repeated such that frontotemporal and temporofrontal streamlines were all captured within the same tract.

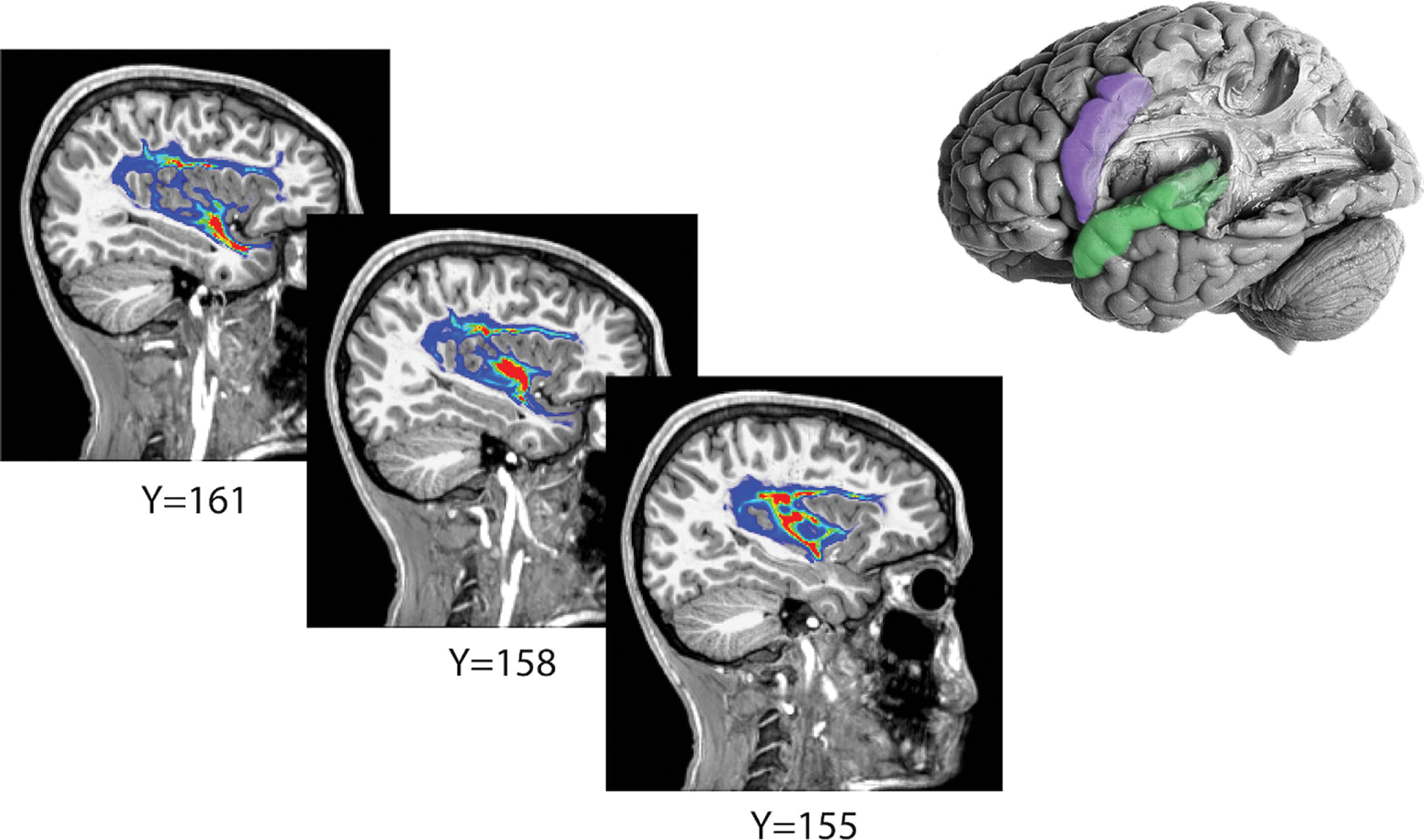

Figure 3: Probabilistic tractography.

To isolate the arcuate fasciculus, white matter tracts were derived between the cortical perisylvian labels (top right, purple and green) using probabilistic tractography, revealing a large white matter tract grossly corresponding to the arcuate fasciculus. An example of probabilistic tractography results is shown here on sagittal slices identified by y-coordinates. Fiber density is visualized with a heat map. An approximation of the cortical termini used for tractography overlaid onto a brain dissection exposing the corresponding arcuate fasciculus is shown in the upper righthand corner (adapted with permission from the Digital Anatomist Program, University of Washington, Seattle).

To explore corticocortical structural connectivity between cortical regions not expected to be involved in the disease process, lobar ROIs (e.g., frontal, parietal, temporal, occipital excluding perisylvian regions) were used as seed and target regions for comparative tractography. As before, these lobar cortices excluded any overlapping regions in the perisylvian label (Figure 2). Ball-and-stick model based probabilistic diffusion tensor tracking (Probtrackx2 through FSL 5.0.4/FDT — FMRIB’s Diffusion Toolbox 3.0; FMRIB’s Software Library) [36] was run between all possible intra- and inter-hemispheric pairs of lobar regions using the same tractography parameters as above.

Neuropsychological testing

A battery of standardized neuropsychological measures was performed by a subspecialty trained clinical neuropsychologist. Phonological awareness was assessed using the Phonological Awareness Index from the Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing, 2nd ed. (CTOPP-2) derived from three composite subscales assessing ability to isolate, blend, and otherwise manipulate and recombine phonemes to derive real words [37]. The Verbal Comprehension Index (VCI) from the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, 5th ed. (WISC-5) provided a measure of ability to formulate language to relay verbal knowledge and concept formation. [38].

The Verbal Fluency subtest from the Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) was used to assess phonemic (letter) fluency, in which the child is asked to generate words that begin with a specified letter, and semantic (category) fluency, in which the child is asked to generate words that fit within a specified category [39]. Sentence repetition was assessed by the Sentence Memory subtest of the Wide Range Assessment of Memory & Learning, 2nd ed. (WRAML-2), where the child listens to and repeats single sentences of increasing length back to the test administrator [40]. Finally, the Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test, 4th ed. (EOWPVT) was used to evaluate expressive vocabulary knowledge at the single word level [41]. All assessments were performed in English.

Statistical analyses

Structural connectivity derived from probabilistic tractography between cortical regions was estimated using a connectivity index [42, 43], defined as the ratio between the number of streamlines launched from the seed ROI and the number of streamlines that successfully terminated in the target ROI. DTI values in superficial ROIs and tract space and the connectivity index were compared between subject groups using two sample one-tailed t-test with the hypotheses that DTI values would be higher and the connectivity index would be lower in SeLECTS compared to controls. Age and sex did not predict diffusion or connectivity in logistic regressions (p>0.1), and were therefore not included as covariates in white matter analyses. Group differences in neuropsychological data between SeLECTS and controls were analyzed using two-sample one-tailed t-tests with the hypothesis that language assessment scores would be lower in children with SeLECTS. Given that abnormalities have been reported to be transient in SeLECTS [13], scores were also compared between children with active SeLECTS and controls. Two-sample t-tests found no group differences in age, and therefore non-age-corrected (raw) language assessment scores were used. Two-sample t-tests found no differences in performance based on sex. For all t-tests, Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests allowed the assumption of normal distributions. To explore the relationship between white matter structure and language function, fractional anisotropy in the perisylvian ROI and inferred arcuate fasciculus, and the connectivity index between perisylvian ROIs were each compared to the performance on each of language assessments using linear regressions. For all analyses, multiple comparisons were accounted for using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to control the false discovery rate (FDR) with q=0.05 [44].

Results

Children with active SeLECTS have statistically worse language function

Performance on a battery of neuropsychological tests assessing language function was compared between children with SeLECTS and age- and sex-matched controls. 25 children with SeLECTS (20M, mean age ± standard deviation (SD) 11.51 ± 1.88 years) and 17 healthy controls (9M, age 11.11 ± 2.41 years) completed neuropsychological testing; there were no differences in age nor sex between the groups (p=0.87 and p=0.31, respectively). Children with SeLECTS performed worse on assessments of phonological awareness (CTOPP-2) and verbal comprehension (WISC-5, VCI) than control youth without SeLECTS (p=0.045 and p=0.050, respectively); scores shown in Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of neuropsychological performance per subject groups

| All SeLECTS subjects (regardless of disease status): | |||

| SeLECTS mean ± std | Control mean ± std | ||

| Phonological Awareness (CTOPP-2) | 26.28 ± 7.95 | 30.29 ± 5.27 | |

| Verbal comprehension (WISC-5 VCI) | 22.43 ± 6.09 | 25.29 ± 4.06 | |

| SeLECTS subjects separated by disease status: | |||

|

Active SeLECTS

mean ± std |

Remission SeLECTS

mean ± std |

Control

mean ± std |

|

| Phonological Awareness (CTOPP-2) | 24.78 ± 8.79 | 28.89 ± 5.69 | 30.29 ± 5.27 |

| Verbal comprehension (WISC-5 VCI) | 21.42 ± 6.40 | 22.40 ± 6.80 | 25.29 ± 4.06 |

| Verbal category fluency (D-KEFS) | 27.92 ± 6.57 | 36.78 ± 9.44 | 34.33 ± 9.69 |

| Verbal letter fluency (D-KEFS) | 20.08 ± 8.46 | 31.44 ± 12.33 | 25.93 ± 9.29 |

| One-Word Expressive Picture Vocab (EOWPVT-4) | 116.46 ± 24.29 | 131.89 ± 23.59 | 128.00 ± 16.95 |

Performance reported by raw score on given language assessment, not age-corrected or ranked by percentile.

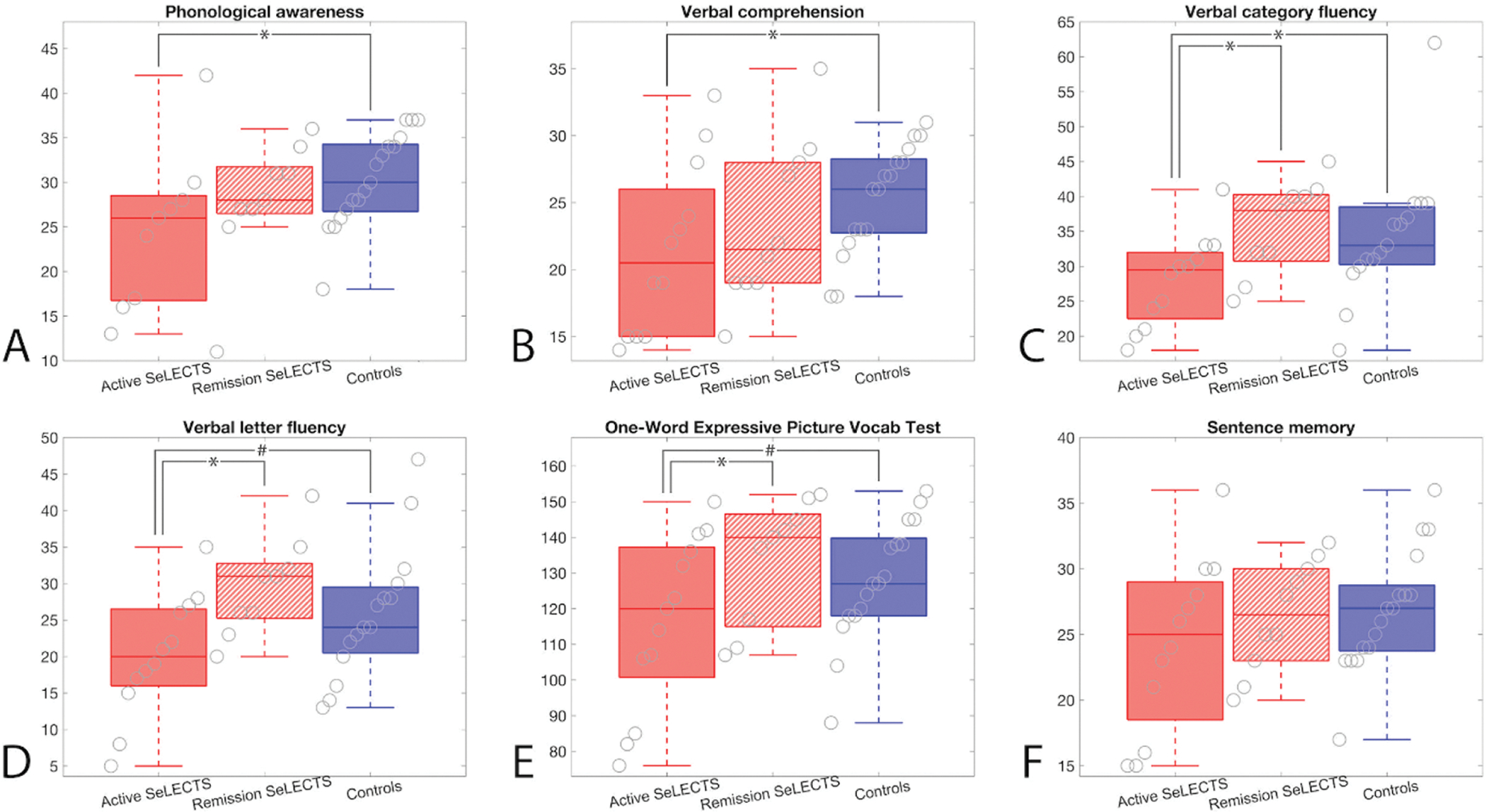

Given the transient nature of the epilepsy and prior reports suggesting transient cognitive symptoms [13,45], we evaluated language performance among SeLECTS children based on disease status, active (n=13; 10M, age 10.85 ± 1.64 years) versus resolved (n=12; 10M, age 12.23 ± 1.92 years). Children with active SeLECTS had statistically significantly reduced performance compared to controls across different language modalities, namely, phonological awareness (CTOPP-2, p=0.028), verbal comprehension (WISC-5 VCI, p=0.028), and verbal category fluency (D-KEFS, p=0.031), with similar trends in verbal letter fluency (D-KEFS, p=0.052), and expressive vocabulary (EOWPVT-4, p=0.068, Figure 4). There was no difference between active SeLECTS, remission or controls on the sentence memory tasks which assess immediate verbal working memory and repetition (WRAML-2, p>0.11). Additionally, children with active SeLECTS perform worse than children with SeLECTS in remission on tests of verbal category fluency (D-KEFS, p=0.009), verbal letter fluency (D-KEFS, p=0.006), and expressive vocabulary (EOWPVT-4, p=0.045) (Figure 4c–e). We note that results remained qualitatively consistent after excluding the two bilingual participants (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 4: Children with active SeLECTS show impaired performance on language tasks.

Children with active SeLECTS perform worse than controls on tests of (A) phonological awareness (CTOPP-2, p=0.028), (B) verbal comprehension (WISC-5 VCI, p=0.028), and (C) verbal category fluency (D-KEFS, p=0.031), with similar trends on tests of (D) verbal letter fluency (D-KEFS, p=0.052) and (E) the expressive one-word picture vocabulary test (EOWPVT-4, p=0.068). Additionally, children with active SeLECTS perform worse than children in remission on tests of (C) verbal category fluency (D-KEFS, p=0.009), (D) verbal letter fluency (D-KEFS, p=0.006), and (E) the expressive one-word picture vocabulary test (EOWPVT-4, p=0.045). (F) There were no differences between groups in performance on sentence memory (WRAML-2, p>0.11). Boxplots indicate mean and interquartile range for each measure.

White matter adjacent to the perisylvian cortex is abnormal in SeLECTS

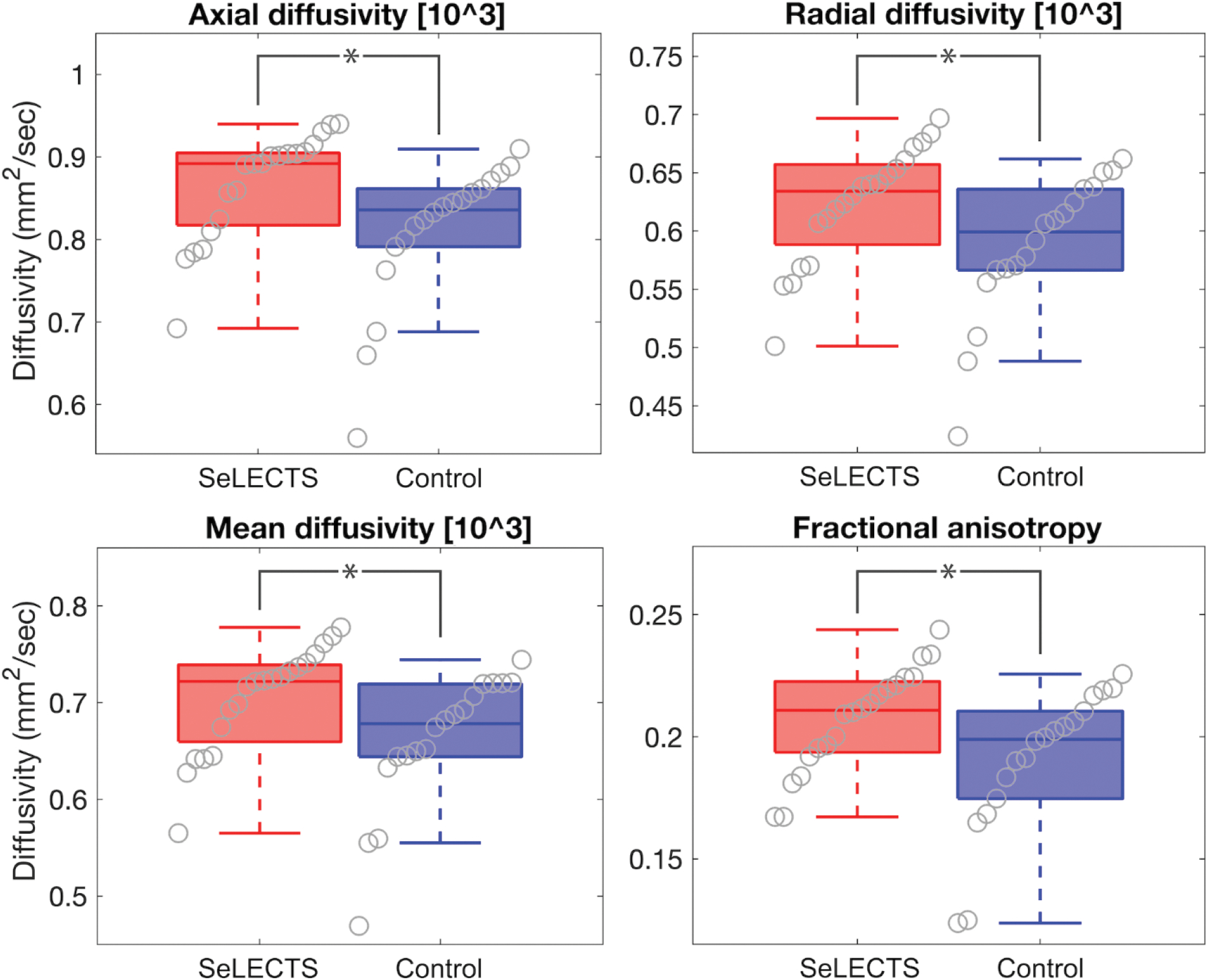

We evaluated left hemispheric white matter that is both adjacent to the perisylvian cortical regions with abnormal electrophysiology in SeLECTS and corresponds to functional cortex involved in language processing [46]. We found abnormal white matter microstructure in children with SeLECTS, characterized by increased diffusivity and fractional anisotropy compared to controls (AD p=0.014, RD p=0.028, MD p=0.020, and FA p=0.024; Figure 5). To verify the contribution of both rolandic and temporal language regions, we evaluated both regions separately and found persistent differences between groups (rolandic: AD p=0.014, RD p=0.030, MD p=0.020, FA p=0.048; superior temporal: AD p=0.037, RD p=0.059, MD p=0.048, FA p=0.037).

Figure 5: Children with SeLECTS have abnormal white matter microstructure in the arcuate fasciculus termini.

All DTI metrics – AD, RD, MD, and FA – are increased in perisylvian regions in SeLECTS compared to controls (AD p=0.014, RD p=0.028, MD p=0.020, FA p=0.024). Boxplots indicate mean and interquartile range for each measure (note that FA is unitless).

To evaluate the regional specificity of these findings, we evaluated the diffusion characteristics of the superficial white matter adjacent to the remaining cortical brain regions. There were no differences in the microstructural properties of the superficial white matter of the whole brain or in any lobe (all p>0.14). Thus, our findings are specific for the inferior rolandic and superior temporal regions, roughly corresponding to the termini of the arcuate fasciculus.

White matter in the arcuate fasciculus tract space is abnormal in SeLECTS

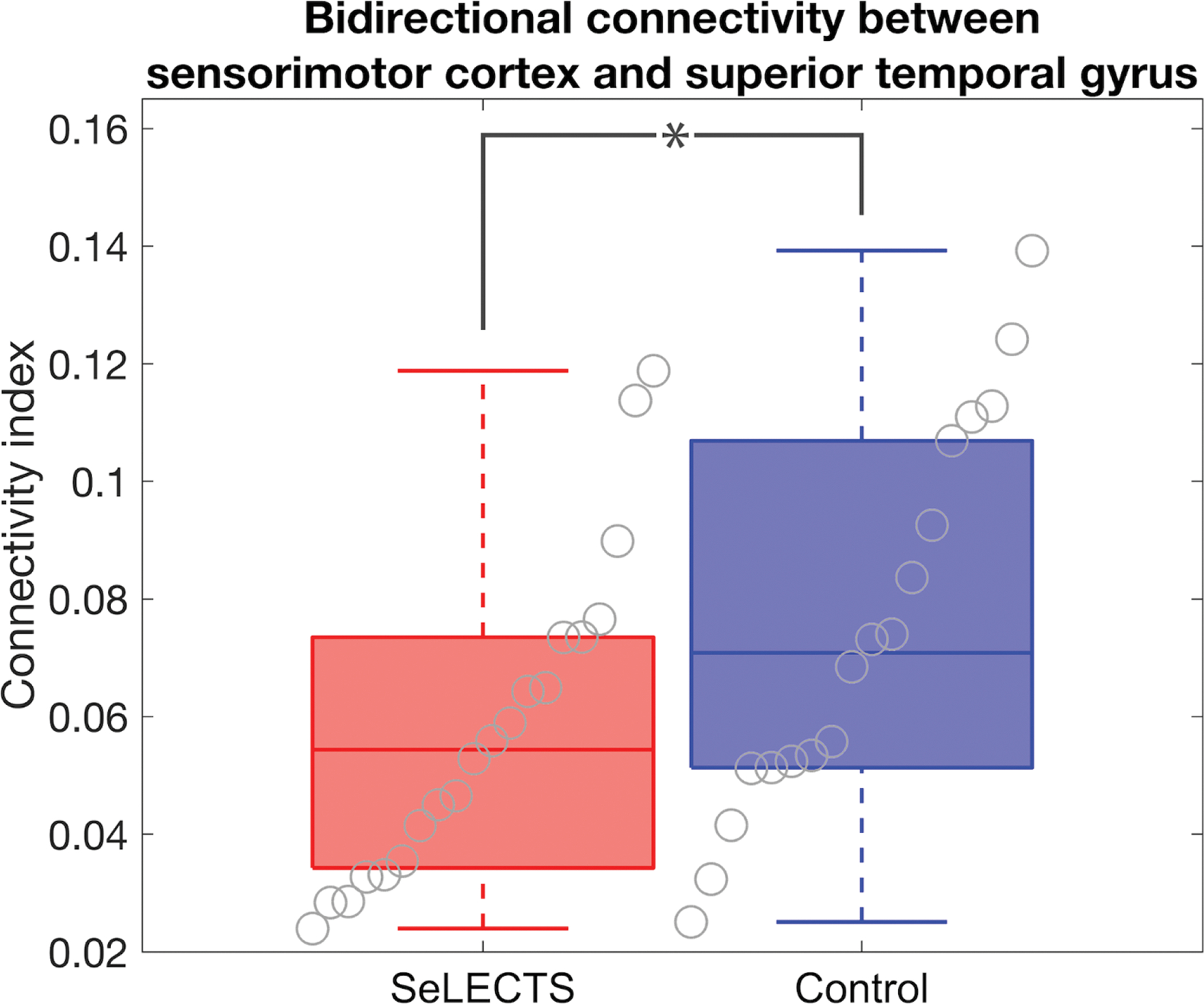

We investigated the structural connectivity and integrity of white matter fibers between perisylvian cortical regions, dominated by the arcuate fasciculus tract, using probabilistic tractography (Figure 3). Structural connectivity of this fiber tract was lower in children with SeLECTS (p=0.045, Figure 6).

Figure 6: Arcuate fasciculus structural connectivity is reduced in SeLECTS.

Structural connectivity between the inferior perirolandic and superior temporal regions was lower connectivity in children with SeLECTS compared to controls (p=0.045). Boxplots indicate mean and interquartile range.

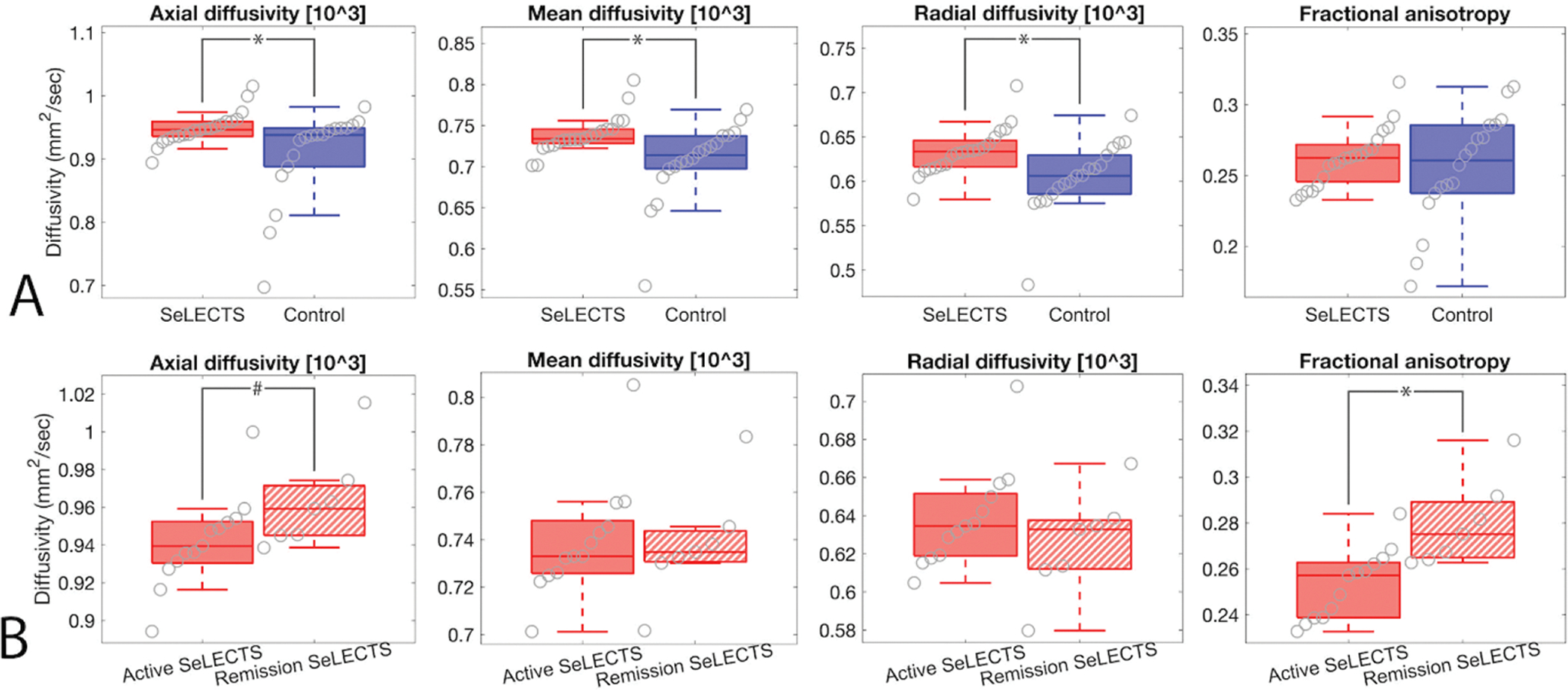

To further characterize the arcuate fasciculus between groups, we evaluated the white matter microstructural properties of the derived tract in children with SeLECTS and controls. We found that children with SeLECTS had increased diffusivity (AD p=0.007, RD p=0.006, MD p=0.016), with no difference in fractional anisotropy (p=0.22) (Figure 7a). To evaluate for changes across disease state, we compared active SeLECTS to remission. We found no difference in AD, RD, or MD in the arcuate fasciculus tract between children with active SeLECTS and in remission (p>0.088 for all tests). However, fractional anisotropy is increased in children with SeLECTS in remission compared to children with active SeLECTS (p=0.003; Figure 7b).

Figure 7: Children with SeLECTS have increased diffusivity in the arcuate fasciculus tract space.

Weighted averages for each metric for voxels within the arcuate fasciculus are shown. Boxplots indicate mean and interquartile range for each measure (note that FA is unitless). (A) Children with SeLECTS have higher diffusivity in this tract (AD p=0.007, MD p=0.016, RD p=0.006), but no difference in FA (p=0.22). (B) FA is increased in children with SeLECTS in remission compared to children with active SeLECTS (p=0.003), with a similar trend in AD (p=0.088). There is no difference in RD or MD between children with active SeLECTS compared to those in remission (p>0.3 for both).

To determine whether abnormal diffusion characteristics were specific to the arcuate fasciculus, we assessed diffusion properties of white matter in the whole brain and subdivided by lobe (frontal, parietal, occipital, temporal). There were no differences in lobar or whole-brain DTI metrics (all p>0.33). We also performed bi-directional tractography between all cortical lobes excluding the perisylvian ROIs to create a proxy index for global structural connectivity. We found no difference in global corticocortical connectivity between children with SeLECTS and controls (p=0.23). Thus, our findings of abnormal white matter microstructural features and macrostructural connectivity are specific to the arcuate fasciculus and the superficial perisylvian white matter, regions necessary for language processing.

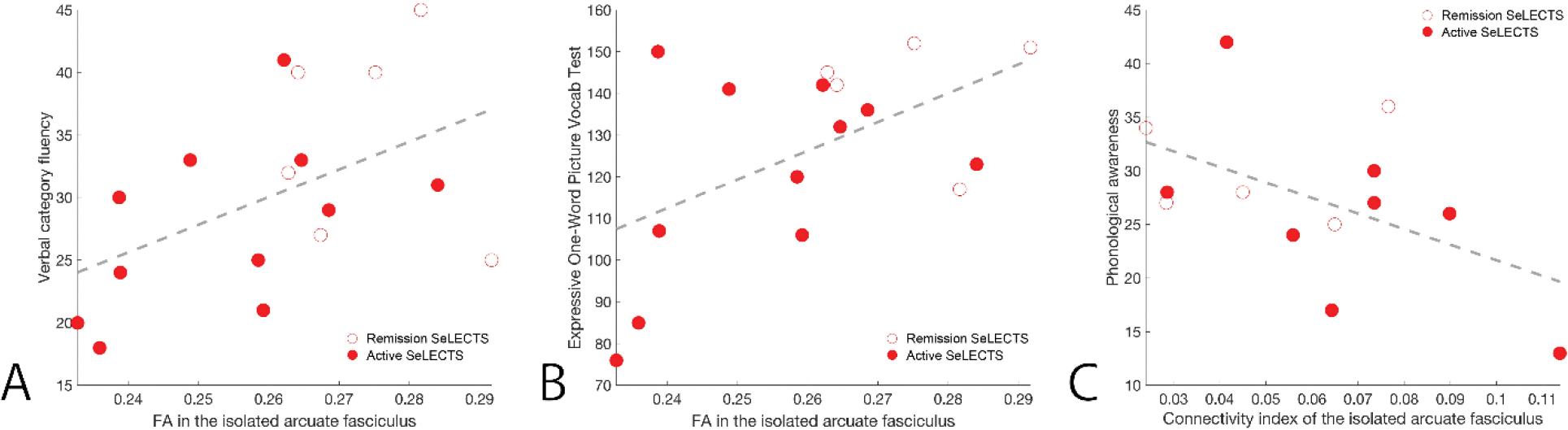

Language performance does not correlate with white matter characteristics

Given the known relationship between the perisylvian brain regions and language function, and the observed abnormalities in both in children with SeLECTS, we performed exploratory tests to identify possible relationships between white matter features and language performance. For this analysis, we tested whether language functions found to be impacted in SeLECTS (phonological awareness, verbal comprehension, verbal category and letter fluencies, and expressive vocabulary) correlated with a summary diffusion measure, fractional anisotropy (FA) in the perisylvian ROI, FA in the arcuate fasciculus, and the arcuate fasciculus connectivity index in all right-handed children with SeLECTS who received both an MRI and neuropsychological testing (n=19, 15M, age 11.38 ± 1.72 years). We found that FA in the arcuate fasciculus positively correlated with verbal category fluency (R2=0.24, p=0.047; Figure 8a) and the expressive one-word picture vocabulary test (R2=0.28, p=0.036; Figure 8b), where children with increased FA performed better on these neuropsychological tasks. We also found a negative linear trend between the connectivity index and phonological awareness (R2=0.26, p=0.074; Figure 8c), such that in children with SeLECTS, decreased structural connectivity in the arcuate fasciculus trended to correlated with better phonological awareness. We note that given the many linear regressions explored, none of these findings pass tests of multiple comparisons, and we treat them instead as exploratory findings of interest.

Figure 8: In children with SeLECTS, arcuate fasciculus microstructure may correlate with performance in some language tests.

In children with SeLECTS, FA in the isolated language tract is positively correlated with (A) verbal category fluency (D-KEFS, R2 = 0.24, p = 0.047) and (B) the expressive one-word picture vocabulary test (EOWPVT-4, R2 = 0.28, p = 0.036). (C) The connectivity index of the isolated language tract is negatively correlated with phonological awareness (CTOPP-2, R2 = 0.26, p = 0.074).

No relationships were found between other assessments of language function and perisylvian RA, arcuate fasciculus FA, or the arcuate fasciculus structural connectivity (Supplementary Figure S1).

Discussion

SeLECTS is a transient developmental epilepsy with a consistent seizure onset zone localized to the centrotemporal cortex bordering the sylvian fissure that commonly presents with language deficits. To better understand the relationship between these anatomical findings and symptoms, we characterized the language profile and white matter microstructural and macrostructural features in a cohort of English-speaking children with SeLECTS [46–50]. We found reduced language performances in this sample of children with SeLECTS, particularly in those with active SeLECTS. We also found distinct abnormalities in the superficial perisylvian white matter adjacent to the seizure onset zone as well as the fibers connecting these regions, the arcuate fasciculus. While this study did not find a relationship between the white matter abnormalities identified and reduced performance on language assessments, these results provide evidence of atypical white matter maturation specific to fibers involved in language processing, which may contribute to language deficiencies commonly comorbid with the disorder.

We characterized several areas of suppressed language development in SeLECTS during the active stage of the disease, which cross-sectionally appear to show promise of recovery throughout remission. A previous natural history study from our group using a different SeLECTS population found complete recovery of neuropsychological deficits, including language function, after disease resolution [13]. Here, we also see a resolution of neurolinguistic symptoms with disease remission, although we cannot extrapolate from the data if cognitive recovery is directly related to seizure resolution or if both stem from a shared structural or pathophysiological process. We also note that although age was not statistically different between any of the subject groups, children in remission were on average 1.38 years older than children with active SeLECTS, and this age difference may have contributed to the improved language performance of children in remission.

Of the six language tests administered to study participants, children with active SeLECTS showed statistically reduced performances on tests of phonological awareness, verbal comprehension, and verbal category fluency, with similar trends in verbal letter fluency and expressive vocabulary. Performance on tests of verbal category fluency, verbal letter fluency, and expressive vocabulary recovered with disease remission. Of note, there were no differences in phonological awareness and verbal comprehension between active and remission SeLECTS, although we note lower average scores in the group with active SeLECTS. It may be that there are some linguistic functions which recover on the same time course with epilepsy remission and some which persist several years past the final seizure. Previous studies have found that some language deficits, including articulation, expressive grammar and literacy skills, persist into remission [11, 51], as opposed to immediate recovery of language functions such as picture naming (aka expressive picture vocabulary) and verbal fluency [52] at the time of interictal epileptic discharge remission, indicating complex and nonlinear normalization of language weakness or impairment over time. In our study, only sentence memory scores were the same across subject groups. Normal sentence memory in SeLECTS has also been reported in a previous study [53]. Parsing the underlying factors for this is an area of potential further investigation given that this task requires fluid integration of multiple aspects of language including speech perception and production, vocabulary knowledge, and grammatical/syntactic processing. Grammar/syntax was not otherwise assessed in this neuropsychological battery and its contribution to this finding cannot be excluded.

SeLECTS presents during a developmental period in which neural network maturation is driven by increased fiber densities between cortical nodes [19], including the corticocortical fiber space of the arcuate fasciculus [54]. Abnormal white matter microstructure in the arcuate fasciculus, the dominant language tract connecting the frontal and temporal language nodes [54] has been previously demonstrated in SeLECTS [10, 55]. Further, impairments or developmental aberrations in language ability have been linked to atypical activation patterns and connectivity on fMRI in frontal and temporal regions in children with SeLECTS [56–58]. In this study, we find spatially specific abnormalities in both superficial and deep white matter and impairment in structural connectivity. As in our prior work [23], we found distinct abnormalities in superficial fibers captured in near-cortical ROIs. We also found increased diffusivity in long-range corticocortical fibers constituting the arcuate fasciculus and impaired structural connectivity, quantified by the connectivity index, between the termini of the arcuate fasciculus. Within the arcuate fasciculus, fractional anisotropy is increased in children with SeLECTS in remission as compared to children with active SeLECTS, coinciding with improved verbal category fluency and picture naming ability, indicating a potential mechanism of recovery.

In order to investigate the connection between structural properties of white matter in SeLECTS and language function, we ran multiple linear regressions exploring the relationships between the six language modalities tested and three structural features: fractional anisotropy in superficial centrotemporal ROIs, fractional anisotropy in the arcuate fasciculus tract identified by probabilistic tractography, and the connectivity index of the tract. We note that these are exploratory analyses and encourage others to attempt to replicate these results of the relationship between language and structural white matter features in developmental epilepsy.

Although it did not withstand correction for multiple comparisons, we found a positive linear relationship between FA in the isolated language tract in SeLECTS and performance on tests of verbal category fluency and the expressive one-word picture vocabulary test. Fractional anisotropy in the arcuate fasciculus has been robustly related to language function. Dyslexia and behavioral predictors of dyslexia are worse in children and adults with lower FA in the arcuate fasciculus [59, 60] and FA in the arcuate fasciculus increases during childhood in superior readers [61]. A recent study [62] found that FA in this tract correlates with the richness of the oral language environment in young children (ages 4–6), where the metric used was the number of conversational turns between child and adult. Further analysis examining nodes along the arcuate fasciculus revealed that the correlation between conversational turns and FA was driven by white matter near the termination of the arcuate fasciculus in the left inferior frontal lobe, the same region we delineate here near sensorimotor cortex.

Of note, we find an evolution of fractional anisotropy within the tract space between children with active SeLECTS and SeLECTS in remission. FA in the arcuate fasciculus is increased between active and remission SeLECTS groups, likely reflecting increased myelination and fiber coherence within the tract space, and children with SeLECTS in remission perform significantly better on the above language function tests than children with active SeLECTS. Thus, the resolution of transient language deficits may coincide with the resolution of microstructural white matter abnormalities and interictal dysfunction in perisylvian language areas on a coordinated time course.

We find a negative linear trend between the connectivity index of the arcuate fasciculus and phonological awareness. The relationship between phonological awareness and structural features of this tract is complex and previous studies have found conflicting results. While some studies have found increased directional coherence within the tract positively relates to phonological awareness [59, 63], other studies have found reduced FA in the left arcuate fasciculus relates to superior phonological processing ability [64], including in professional translators [65] and expert phoneticians [66]. Similarly, professional musicians have been found to have reduced FA in the corticospinal tract [67]. Given that endpoints of the arcuate fasciculus are diffuse and variable, and often contain incoherently oriented axons, this inverse relationship may be explained by greater branching of arcuate fasciculus axons, particularly near cortical termini, or experience-dependent pruning of axons within the fiber bundle [64]. In this case, the negative trend between phonological awareness and the connectivity index may be driven by crossing fibers with greater integration from various cortical regions, yielding greater functional performance. We also note that epileptic processes may drive language reorganization in the affected epileptic brain [57, 68, 69], such that the brain regions driving phonological awareness and complex language integration in SeLECTS have spatially shifted from classical language ROIs, or shifted to involved more bilateral language representation [56, 57].

These findings provide yet further evidence that focal developmental epilepsy involves focal structural abnormalities that can be detected and quantified using modern neuroimaging techniques, and offer insight into the relationship between these structural abnormalities, cortical connectivity, and neuropsychological deficits of developmental epilepsy. Further studies are needed to better illuminate the relationship between language and structural white matter features in epilepsy, as well as the relationship between white matter integrity and the seizures and abnormal cortical physiology present in children with SeLECTS. It will be difficult to know if a direct, linear relationship links developmentally delayed language function and aberrant white matter maturation in this epilepsy disorder until more studies are undertaken. Overall, this work contributes to a greater understanding of focal microstructural alterations in focal epilepsy and indicates potential biological processes underlying comorbid language deficits in a common childhood epilepsy syndrome.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure S1: All linear regressions for analyses of white matter and language function

Children with SeLECTS show reduced performance on language assessments

Language assessment scores are worse in children with active SeLECTS than those in children in remission

White matter micro- and macrostructure are abnormal in regions constituting language networks in SeLECTS

Connectivity between language networks nodes is abnormal in SeLECTS

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Amy Morgan for her assistance in the conceptualization and planning of the neuropsychological testing battery, Emily L. Thorn, McKenna Parnes, and Amy Morgan for their assistance with data collection for this project, and the participants and their families for their support.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [NIH NINDS R01NS115868].

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Scheffer IE, Berkovic S, Capovilla G, Connolly MB, French J, Guilhoto L, et al. ILAE classification of the epilepsies: Position paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia 2017;58:512–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Astradsson A, Olafsson E, Ludvigsson P, Björgvinsson H, Hauser WA. Rolandic epilepsy: An incidence study in Iceland. Epilepsia 1998;39:884–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Berg AT, Shinnar S, Levy SR, Testa FM. Newly diagnosed epilepsy in children: Presentation at diagnosis. Epilepsia 1999;40:445–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Callenbach PMC, Bouma PAD, Geerts AT, Arts WFM, Stroink H, Peeters EAJ, et al. Long term outcome of benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes: Dutch study of epilepsy in childhood. Seizure 2010;19:501–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Berg AT, Berkovic SF, Brodie MJ, Buchhalter J, Cross JH, Van Emde Boas W, et al. Revised terminology and concepts for organization of seizures and epilepsies: Report of the ILAE Commission on Classification and Terminology, 2005–2009. Epilepsia 2010;51:676–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Baumer FM, Cardon AL, Porter BE. Language dysfunction in pediatric epilepsy. J Pediatr 2018;194:13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cerminara C, D’Agati E, Lange KW, Kaunzinger I, Tucha O, Parisi P, et al. Benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes and the multicomponent model of attention: A matched control study. Epilepsy Behav 2010;19:69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Garcia-Ramos C, Jackson DC, Lin JJ, Dabbs K, Jones JE, Hsu DA, et al. Cognition and brain development in children with benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes. Epilepsia 2015;56:1615–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Jurkevičiene G, Endziniene M, Laukiene I, Šaferis V, Rastenyte D, Plioplys S, et al. Association of language dysfunction and age of onset of benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes in children. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2012;16:653–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kim SE, Lee JH, Chung HK, Lim SM, Lee HW. Alterations in white matter microstructures and cognitive dysfunctions in benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes. Eur J Neurol 2014;21:708–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Monjauze C, Tuller L, Hommet C, Barthez MA, Khomsi A. Language in benign childhood epilepsy with centro-temporal spikes abbreviated form: Rolandic epilepsy and language. Brain Lang 2005;92:300–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Riva D, Vago C, Franceschetti S, Pantaleoni C, D’Arrigo S, Granata T, et al. Intellectual and language findings and their relationship to EEG characteristics in benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes. Epilepsy Behav 2007;10:278–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ross EE, Stoyell SM, Kramer MA, Berg AT, Chu CJ. The natural history of seizures and neuropsychiatric symptoms in childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (CECTS). Epilepsy Behav 2020;103(Pt A):106437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wierenga LM, van den Heuvel MP, van Dijk S, Rijks Y, de Reus MA, Durston S. The development of brain network architecture. Hum Brain Mapp 2016;37:717–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hagmann P, Sporns O, Madan N, Cammoun L, Pienaar R, Wedeen VJ, et al. White matter maturation reshapes structural connectivity in the late developing human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2010;107:19067–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Tamnes CK, Østby Y, Fjell AM, Westlye LT, Due-Tønnessen P, Walhovd KB. Brain maturation in adolescence and young adulthood: Regional age-related changes in cortical thickness and white matter volume and microstructure. Cereb Cortex 2010;20:534–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lebel C, Gee M, Camicioli R, Wieler M, Martin W, Beaulieu C. Diffusion tensor imaging of white matter tract evolution over the lifespan. Neuroimage 2012;60:340–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Huang H, Shu N, Mishra V, Jeon T, Chalak L, Wang ZJ, et al. Development of human brain structural networks through infancy and childhood. Cereb Cortex 2015;25:1389–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Dennis EL, Jahanshad N, McMahon KL, de Zubicaray GI, Martin NG, Hickie IB, et al. Development of brain structural connectivity between ages 12 and 30: A 4-Tesla diffusion imaging study in 439 adolescents and adults. Neuroimage 2013;64:671–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Widjaja E, Skocic J, Go C, Snead OC, Mabbott D, Smith ML. Abnormal white matter correlates with neuropsychological impairment in children with localization-related epilepsy. Epilepsia 2013;54:1065–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ciumas C, Saignavongs M, Ilski F, Herbillon V, Laurent A, Lothe A, et al. White matter development in children with benign childhood epilepsy with centro-temporal spikes. Brain 2014;137:1095–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Xiao F, Chen Q, Yu X, Tang Y, Luo C, Fang J, et al. Hemispheric lateralization of microstructural white matter abnormalities in children with active benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (BECTS): A preliminary DTI study. J Neurol Sci 2014;336:171–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ostrowski LM, Song DY, Thorn EL, Ross EE, Stoyell SM, Chinappen DM, et al. Dysmature superficial white matter microstructure in developmental focal epilepsy. Brain Commun 2019;1:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Jiang Y, Song L, Li X, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Jiang S, et al. Dysfunctional white-matter networks in medicated and unmedicated benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes. Hum Brain Mapp 2019;40:3113–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Spencer ER, Chinappen D, Emerton BC, Morgan AK, Hämäläinen MS, Manoach DS, et al. Source EEG reveals that Rolandic epilepsy is a regional epileptic encephalopathy. NeuroImage Clin 2022;33:102956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Fisher RS, Acevedo C, Arzimanoglou A, Bogacz A, Cross JH, Elger CE, et al. ILAE Official Report: A practical clinical definition of epilepsy. Epilepsia 2014;55:475–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wickens S, Bowden SC, D’Souza W. Cognitive functioning in children with self-limited epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Epilepsia 2017;58:1673–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Fischl B FreeSurfer. NeuroImage 2012;62:774–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Desikan RS, Ségonne F, Fischl B, Quinn BT, Dickerson BC, Blacker D, et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage 2006;31:968–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Loiseau P, Beaussart M. The seizures of benign childhood epilepsy with rolandic paroxysmal discharges. Epilepsia 1973;14:381–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Chang EF, Raygor KP, Berger MS. Contemporary model of language organization: An overview for neurosurgeons. J Neurosurg 2015;122:250–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Destrieux C, Fischl B, Dale A, Halgren E. Automatic parcellation of human cortical gyri and sulci using standard anatomical nomenclature. Neuroimage 2010;53:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Behrens TEJ, Woolrich MW, Jenkinson M, Johansen-Berg H, Nunes RG, Clare S, et al. Characterization and propagation of uncertainty in diffusion-weighted MR imaging. Magn Reson Med 2003;50:1077–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Bain JS, Yeatman JD, Schurr R, Rokem A, Mezer AA. Evaluating arcuate fasciculus laterality measurements across dataset and tractography pipelines. Hum Brain Mapp 2019;40:3695–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Rilling J, Glasser M, Jbabdi S, Andersson J, Preuss T. Continuity, divergence, and the evolution of brain language pathways. Front Evol Neurosci 2012;3:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Behrens TEJ, Berg HJ, Jbabdi S, Rushworth MFS, Woolrich MW. Probabilistic diffusion tractography with multiple fibre orientations: What can we gain? Neuroimage 2007;34:144–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Wagner RK, Torgesen JK, Rashotte CA, Pearson N: The comprehensive test of phonological processing. (CTOPP-2). 2nd ed. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Wechsler D: Wechsler intelligence scale for children. 5th ed. Bloomington, MN: Pearson; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Delis DC, Kaplan E, Kramer JH: Delis-Kaplan executive function scale. San Antonio, TX: Psychol. Corp; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Sheslow D, Adams W: Wide range assessment of memory and learning. 2nd ed. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Martin NA, Brownell R: Expressive one-word picture vocabulary test, 4th ed. Novato, CA: Academic Therapy Publications; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [42].McNab JA, Edlow BL, Witzel T, Huang SY, Bhat H, Heberlein K, et al. The human connectome project and beyond: Initial applications of 300 mT/m gradients. Neuroimage 2013;80:234–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Chu CJ, Tanaka N, Diaz J, Edlow BL, Wu O, Hämäläinen M, et al. EEG functional connectivity is partially predicted by underlying white matter connectivity. Neuroimage 2015;108:23–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Deonna T, Zesiger P, Davidoff V, Maeder M, Mayor C, Roulet E. Benign partial epilepsy of childhood: A longitudinal neuropsychological and EEG study of cognitive function. Dev Med Child Neurol 2000;42:595–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Arsenault JS, Buchsbaum BR. Distributed neural representations of phonological features during speech perception. J Neurosci 2015;35:634–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Bouchard KE, Chang EF. Control of spoken vowel acoustics and the influence of phonetic context in human speech sensorimotor cortex. J Neurosci 2014;34:12662–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Catani M, Allin MPG, Husain M, Pugliese L, Mesulam MM, Murray RM, et al. Symmetries in human brain language pathways correlate with verbal recall. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2007;104:17163–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Catani M, Jones DK, Ffytche DH. Perisylvian language networks of the human brain. Ann Neurol 2005;57:8–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Cheung C, Hamiton LS, Johnson K, Chang EF. The auditory representation of speech sounds in human motor cortex. Elife 2016;5:e12577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Törnhage M, Sandberg EN, Lundberg S. Oromotor, word retrieval, and dichotic listening performance in young adults with previous Rolandic epilepsy. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2020;25:139–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Baglietto MG, Battaglia FM, Nobili L, Tortorelli S, De Negri E, Calevo MG, et al. Neuropsychological disorders related to interictal epileptic discharges during sleep in benign epilepsy of childhood with centrotemporal or Rolandic spikes. Dev Med Child Neurol 2007;43:407–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Lillywhite LM, Saling MM, Simon HA, Abbott DF, Archer JS, Vears DF, et al. Neuropsychological and functional MRI studies provide converging evidence of anterior language dysfunction in BECTS. Epilepsia 2009;50:2276–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Ashtari M, Cervellione KL, Hasan KM, Wu J, McIlree C, Kester H, et al. White matter development during late adolescence in healthy males: A cross-sectional diffusion tensor imaging study. Neuroimage 2007;35:501–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Kim HH, Chung GH, Park SH, Kim SJ. Language-related white-matter-tract deficits in children with benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes: A retrospective study. J Clin Neurol 2019;15:502–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Besseling RMH, Jansen JFA, Overvliet GM, Van Der Kruijs SJM, Ebus SCM, De Louw A, et al. Aberrant functional connectivity between motor and language networks in rolandic epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 2013;107:253–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Datta AN, Oser N, Bauder F, Maier O, Martin F, Ramelli GP, et al. Cognitive impairment and cortical reorganization in children with benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes. Epilepsia 2013;54:487–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Wu Y, Fang F, Li K, Jin Z, Ren X, Lv J, et al. Functional connectivity differences in speech production networks in Chinese children with Rolandic epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2022;108819:ePub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Saygin ZM, Norton ES, Osher DE, Beach SD, Cyr AB, Ozernov-Palchik O, et al. Tracking the roots of reading ability: White matter volume and integrity correlate with phonological awareness in prereading and early-reading kindergarten children. J Neurosci 2013;33:13251–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Vandermosten M, Boets B, Poelmans H, Sunaert S, Wouters J, Ghesquière P. A tractography study in dyslexia: Neuroanatomic correlates of orthographic, phonological and speech processing. Brain 2012;135(Pt 3):935–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Yeatman JD, Dougherty RF, Ben-Shachar M, Wandell BA. Development of white matter and reading skills. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:E3045–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Romeo RR, Segaran J, Leonard JA, Robinson ST, West MR, Mackey AP, et al. Language exposure relates to structural neural connectivity in childhood. J Neurosci 2018;38:7870–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Frye RE, Liederman J, Hasan KM, Lincoln A, Malmberg B, McLean J, et al. Diffusion tensor quantification of the relations between microstructural and macrostructural indices of white matter and reading. Hum Brain Mapp 2011;32:1220–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Yeatman JD, Dougherty RF, Rykhlevskaia E, Anthony J, Hall J. Anatomical properties of the arcuate fasciculus predict phonological and reading skills in children. J Cogn Neurosci 2011;23:3304–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Elmer S, Hänggi J, Vaquero L, Cadena GO, François C, Rodríguez-Fornells A. Tracking the microstructural properties of the main white matter pathways underlying speech processing in simultaneous interpreters. Neuroimage 2019;191:518–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Vandermosten M, Price CJ, Golestani N. Plasticity of white matter connectivity in phonetics experts. Brain Struct Funct 2016;221:3825–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Imfeld A, Oechslin MS, Meyer M, Loenneker T, Jancke L. White matter plasticity in the corticospinal tract of musicians: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Neuroimage 2009;46:600–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Oser N, Hubacher M, Specht K, Datta AN, Weber P, Penner IK. Default mode network alterations during language task performance in children with benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (BECTS). Epilepsy Behav 2014;33:12–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Monjauze C, Broadbent H, Boyd SG, Neville BG, Baldeweg T. Language deficits and altered hemispheric lateralization in young people in remission from BECTS. Epilepsia 2011;52:e79–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure S1: All linear regressions for analyses of white matter and language function