Summary

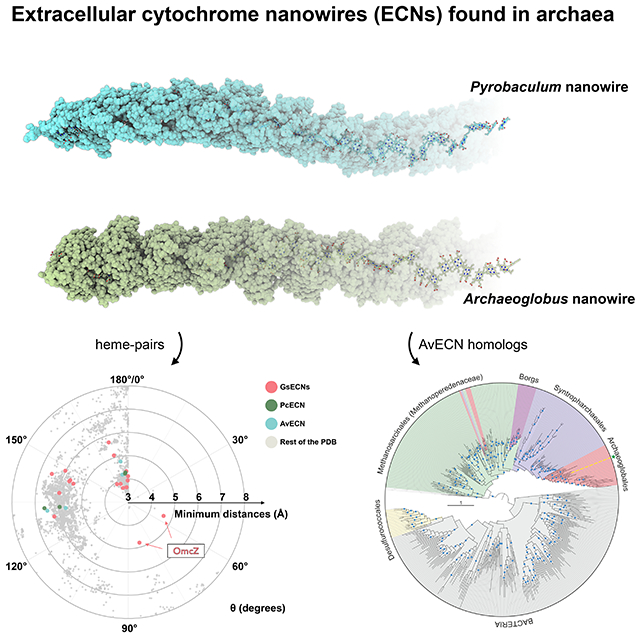

Electrically conductive appendages from the anaerobic bacterium Geobacter sulfurreducens, recently identified as extracellular cytochrome nanowires (ECNs), have received wide attention due to numerous potential applications. However, whether other organisms employ similar ECNs for electron transfer remains unknown. Here, using cryo-electron microscopy, we describe the atomic structures of two ECNs from two major phyla of hyperthermophilic archaea present in deep-sea hydrothermal vents and terrestrial hot springs. Homologs of Archaeoglobus veneficus ECN are widespread among mesophilic methane-oxidizing Methanoperedenaceae, alkane-degrading Syntrophoarchaeales archaea, and in the recently described megaplasmids called Borgs. The ECN protein subunits lack similarities in their folds; however, they share a common heme arrangement, suggesting an evolutionarily optimized heme packing for efficient electron transfer. The detection of ECNs in archaea suggests that filaments containing closely stacked hemes may be a common and widespread mechanism for long-range electron transfer in both prokaryotic domains of life.

Keywords: microbial nanowires, extracellular cytochrome nanowires, cytochrome filaments, cryo-EM

Graphical Abstract

In Brief for the manuscript

Heme organization rather than protein structure is conserved in nanowire cytochrome filaments from archaea and bacteria.

Introduction

In anoxic environments, from aquatic sediments to the human gut, respiring bacteria naturally transfer electrons across micron-scale distances beyond their outer membranes to distant and insoluble terminal electron acceptors.1–3 It is hypothesized that long-range electron transfer played an important role in microbial metabolism on the early earth, when iron as Fe(II) was the most accessible transition metal, with Fe(III) being a potential electron acceptor due to the presence of small amounts of Fe(III) at low levels of oxygen.4 Fe(III) could have been present as hematite or magnetite, necessitating the presence of extracellular nanowires so the different Fe(III) compounds could be used as terminal electron acceptors. Other processes benefitting from bacterial nanowires include direct interspecies electron transfer (DIET), which paves the way for energetic coupling between different species in diverse anaerobic microbial communities.5 For instance, recent reports indicated that nanowire-mediated DIET prevails in certain anaerobic digesters and can provide electrons for the reduction of CO2 to CH4.6 Furthermore, microbial nanowire-mediated DIET has also been reported to contribute to the key environmental processes, such as anaerobic oxidation of methane coupled to sulfate reduction,7,8 anaerobic photosynthesis,9 and anoxic, dark carbon fixation.10 However, the molecular underpinnings of long distance electron transfer have only been identified in the soil bacterium Geobacter sulfurreducens.11

G. sulfurreducens has been extensively studied as a model organism to understand the structure and function of conductive extracellular nanowires. The identity of the conductive filamentous appendages enabling extracellular electron transfer (EET) has been a topic of active debate.11 With major technological advances in cryo-EM,12,13 the microbial nanowires in G. sulfurreducens have been shown to be polymerized filamentous extracellular cytochromes, containing either OmcS,14,15 OmcE16 or OmcZ.17 On the other hand, the notion that these extracellular filaments are 3nm diameter “e-pili”, containing only the N-terminal chain of the type IV pilin, PilA-N, has now been debunked with the determination of an actual structure for the PilA filament, showing that it is composed of two chains and is incompatible with electron transport.16,18

The multi-heme c-type cytochromes OmcS, OmcE, and OmcZ have protein structures that are ~80% loops, lacking extensive secondary structure and a conserved structural fold. However, comparing the heme arrangements in the polymerized filaments, these three ECNs fall into two different categories. OmcE and OmcS have very similar heme arrangements, and their hemes are insulated from solvent by a protein shield, consistent with a model where nanowires link a cell to a nearby metal oxide particle.16 In contrast, OmcZ possesses an entirely different heme arrangement, with each subunit containing a branched solvent-exposed heme in addition to the linear chain of hemes, so that networks of OmcZ filaments may form a conductive biofilm with a multiplicity of paths for electron flow.17 With the large number of multi-heme cytochromes found in prokaryotic genomes, and the observed significant difference in heme arrangements, it is likely that conductive ECNs have arisen multiple times during evolution, and it was hypothesized that species other than Geobacter could also produce ECNs.11 Although multi-heme cytochromes encoded by methanotrophic archaea were predicted to mediate DIET 7, no evidence of ECN existence outside of G. sulfurreducens has been presented thus far.

Here, we validate the hypothesis that ECNs are not restricted to G. sulfurreducens and discover such filaments in the second prokaryotic domain of life, the Archaea. Using cryo-EM, we determined atomic structures of extracellular cytochrome filaments from two species of hyperthermophilic archaea, Pyrobaculum calidifontis and Archaeoglobus veneficus, belonging to two different phyla. Our observations suggest ECNs may be ubiquitous in both prokaryotic domains and mediate long-range extracellular electron transfer in diverse microbial communities.

Results

Multi-heme c-type cytochrome filaments exist in archaeal strains

In archaea, genes encoding multi-heme c-type cytochrome were previously predicted in two major phyla, Euryarchaeota (orders Archaeoglobales and Methanosarcinales) and Crenarchaeota (orders Thermoproteales and Desulfurococcales).19 To identify potential ECN candidates among the predicted multi-heme c-type cytochrome proteins, we applied the following filters that matched the expected features of ECN the proteins had to possess a predicted signal peptide, lack predicted transmembrane regions (outside of the signal peptide), be encoded with other multi-heme c-type cytochromes in the same strain, and lack sequence homology to an annotated enzyme fold. From a set of multi-heme c-type cytochromes that matched our criteria, for validation we selected three ECN candidates, from P. calidifontis (order Thermoproteales), A. veneficus (order Archaeoglobales), and Methanolobus tindarius (order Methanosarcinales). Cryo-EM analysis showed that P. calidifontis and A. veneficus each expressed an ECN: PcECN showed no obvious similarity to any previously determined protein fold; AvECN also presented a new protein fold, although distantly related to c552-family cytochromes (see below).

Cryo-EM of P. calidifontis ECN

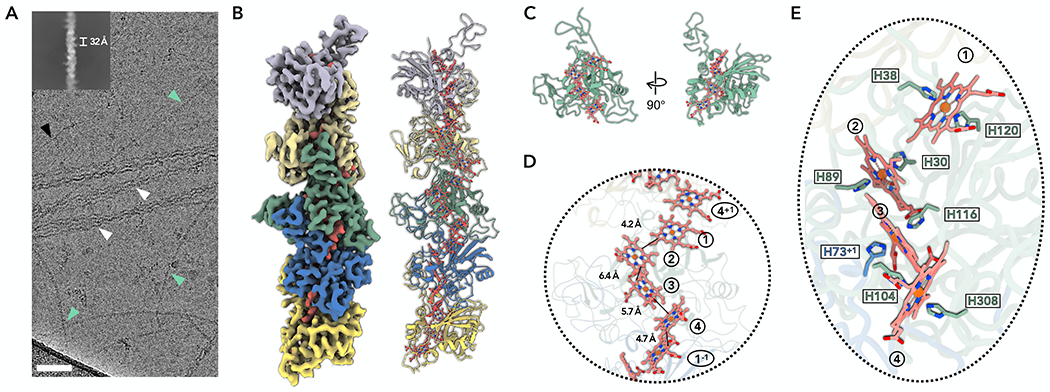

We grew WT P. calidifontis (DSM 21063)20 using sodium thiosulfate as the electron acceptor under microaerobic conditions. This environment promotes not only the production of cytochrome filaments but also other types of cell appendages, including biofilm-promoting TasA-like bundling filaments21, type IV pili, and conjugation pili (PDB 8DFT). Images of ECN segments were easily separated from other types of filaments in reference-free 2D classifications. Unlike Geobacter OmcS filaments, P. calidifontis ECN (PcECN) does not display a sinusoidal morphology (Fig. 1A). An averaged power spectrum from aligned raw particles shows a meridional layer-line at ~1/(32 Å) and a layer-line that can only be arising from a 1-start helix at ~1/(215 Å), establishing that there are ~6.6 subunits per turn of a ~215 A pitch 1-start helix (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1. Cryo-EM of P. calidifontis ECN.

(A) Cryo-EM image of cell appendages from P. calidifontis cells. Different species of filaments were observed and labeled correspondingly: PcECN (green arrowheads); Archaeal bundling pili subunit, AbpA (white arrowheads); B-form DNA (black arrowhead). Scale bar, 50 nm. The upper left is a two-dimensional class average of the PcECN, showing the rise of 32 Å between adjacent subunits.

(B) The cryo-EM reconstruction (left) with backbone trace of the PcECN subunits (right). The heme molecules and their corresponding cryo-EM densities are shown in red. Each PcECN subunit is colored differently.

(C) The atomic model of one repeating subunit of PcECN. The protein backbone trace is green, and the heme molecules are shown in ball and stick representation in red.

(D) A close-up view of the filament to show the heme array in PcECN, with the minimum observed edge-to-edge distances indicated between adjacent porphyrin rings. Heme molecules are labeled with numbers in circles, “+1” and “−1” indicate protein subunits above and below the central subunit, respectively.

(E) The heme array in PcECN and the histidines coordinating these hemes. The histidines are colored by protein subunits using the same color scheme as in panel B.

The final reconstruction reached 3.8 Å resolution with the application of helical symmetry. The 1-start helix was right-handed, determined by the hand of α-helices in the protein subunit, with a rise and rotation per subunit of 32.4 Å and 54.7°, respectively. The Cα tracing at such a resolution was straightforward, and afte accounting for the protein density, the map showed that each ECN subunit contains four hemes. Finding the correct protein was unambiguous as the P. calidifontis strain only encodes four proteins having more than two CxxCH heme-binding motifs: A3MW89 (four motifs), A3MW92 (three motifs), A3MW94 (eight motifs), and A3MW99 (eight motifs). Therein, A3MW94 and A3MW99 are excluded due to the much larger number of predicted heme molecules per subunit. AlphaFold222 predictions of A3MW89 and A3MW92 were compared with the cryo-EM map. All side chains of A3MW92 agreed with the cryo-EM map. The presence of four hemes per subunit in the experimental map, but only three CxxCH heme-binding motifs in A3MW92, is explained by the filament model (see below). The AlphaFold2 prediction for A3MW89, the only protein having four heme-binding motifs, on the other hand, does not have an overall protein fold matching the cryo-EM map (Supplementary Fig. 2). Thus, A3MW92 was uniquely identified as the ECN protein in P. calidifontis. The model starts at the position 24 of the predicted protein, suggesting that A3MW92 is N-terminally processed. Consistent with this observation, A3MW92 has a strongly predicted (P=0.97) signal peptide23 with a signal peptidase I cleavage site between positions Ala20 and Thr21 (Supplementary Fig. 3A–B). These results suggest that PcECN is externalized using the Sec secretion system.

Interestingly, the PcECN model has a considerably higher percentage of secondary structure content (15% α-helices, 18% β-strands; Fig. 1C) compared to G. sulfurreducens ECNs: OmcS has 13% α-helices and 6% β-strands; OmcE has 19% α-helices and 3% β-strands; OmcZ has 18% α-helices and 4% β-strands. We have previously shown that G. sulfurreducens ECNs do not have a conserved protein fold14,16,17, presumably because the key selection during evolution would be on maintaining the closely stacked heme arrangements, which would be possible without a conserved protein fold. We then asked whether PcECN has a structural fold similar to other known protein structures since its secondary structure content is ~10% higher. However, neither DALI24 nor Foldseek25 could identify a known experimentally determined structure having a similar fold, suggesting that PcECN has a fold never before seen in existing databases.

Despite having no protein fold similarity, the heme arrangements in the PcECN model are strikingly similar to those in the G. sulfurreducens OmcS and OmcE filaments. The neighboring heme porphyrin rings in the PcECN adopt either face-to-face antiparallel or T-shaped conformations, and those conformations take place alternately along the filament (Fig. 1C–D). Furthermore, the edge-to-edge distances between porphyrin rings are comparable to OmcS/E, ranging from 4.2-6.4 Å (Fig. 1D), suggesting a similar electron transfer mechanism. In addition, similar to OmcS/E, one heme (heme 3) per PcECN subunit is coordinated by H116 of the same subunit and H73 of an adjacent subunit (Fig. 1E). Notably, the optimal growth condition for P. calidifontis is 90 °C, significantly higher than G. sulfurreducens (30 °C). The required extra thermostability of PcECN may be contributed by two intra-subunit disulfide bonds that were not observed in G. sulfurreducens ECNs (Supplementary Fig. 4). Furthermore, similar to other extracellular filaments of hyperthermophilic archaea, including type IV pili26,27, bundling pili21 and flagella28, but unlike OmcS/OmcZ of G. sulfurreducens, PcECN appear to be glycosylated.

Cryo-EM of A. veneficus ECN

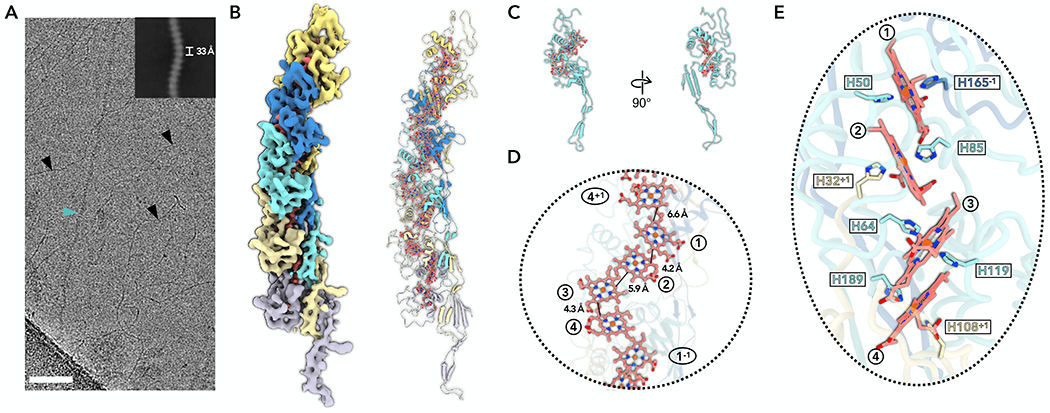

To obtain A. veneficus ECNs (AvECN), we grew wt A. veneficus cells (DSM 11195) 29 with sodium sulfite as the electron acceptor. Cryo-EM analysis of the AvECN (Fig. 2) showed that the filament has a strong sinusoidal morphology with a pitch of ~350 Å. An averaged power spectrum from aligned raw particles showed a meridional layer-line at ~1/(33 Å), establishing a helical rise of ~33 Å, and therefore a helical twist of ~34°. After refining those parameters in the helical and subsequent non-uniform refinement, a ~4.1 Å resolution reconstruction, judged by model:map Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC) (Supplementary Table 1), was generated.

Figure 2. Cryo-EM of A. veneficus ECN.

(A) Cryo-EM image of cell appendages from A. veneficus cells. Different filaments were observed and labeled correspondingly: AvECN (cyan arrowhead); B-form DNA (black arrowheads). Scale bar, 50 nm. The upper right is a two-dimensional class average of the AvECN filament, showing the rise of 33 Å between adjacent subunits.

(B) The cryo-EM reconstruction (left) with backbone trace of the AvECN subunits (right). The heme molecules and their corresponding cryo-EM densities are shown in red. Each AvECN subunit is colored differently.

(C) The atomic model of one repeating subunit of AvECN. The protein backbone trace is cyan, and the heme molecules are shown in ball and stick representation in red.

(D) A close-up view of the filament to show the heme array in AvECN, with the minimum observed edge-to-edge distances indicated between adjacent porphyrin rings. Heme molecules are labeled with numbers in circles, “+1” and “−1” indicate protein subunits above and below the central subunit, respectively.

(E) The heme array in AvECN and the histidine coordination of the hemes. The histidines are colored by protein subunits using the same color scheme as in panels B and C.

By tracing the protein chain, it was apparent that each AvECN subunit also contains four heme molecules (Fig. 2B–E), as was found for the PcECN. Interestingly, 17 proteins with three or more CxxCH motifs are present in the A. veneficus proteome. Among them, the AlphaFold predictions of only three, F2KMU7, F2KMU8, and F2KPF5, have a similar protein fold to the experimental chain trace and roughly agree with the cryo-EM map. After further investigation, F2KMU7 was excluded because it has a helix-rich region (residues 120-150) that cannot be explained by the cryo-EM map. Similarly, F2KPF5 was also excluded because it does not have enough residues to fit a loop region in the cryo-EM map (residues 131-151 in F2KPF5, while the corresponding loop in F2KMU8 contained residues 136-164). F2KMU8 can be fully built into the cryo-EM map and was therefore uniquely identified as the AvECN protein in A. veneficus (Supplementary Fig. 2). Similar to the PcECN, AvECN has a predicted N-terminal signal peptide23 with the cleavage site located between Ser26 and Leu27 and is thus also likely transported across the membrane through the Sec secretion system (Supplementary Fig. 3C–D).

The AvECN has an even higher percentage of secondary structure content than PcECN, with 29% α-helices and 15% β-strands (Fig. 2C). Strikingly, even with 44% of the residues in either α-helices or β-strands, DALI24 and Foldseek25 failed to identify a similar known experimentally determined protein fold. The AvECN fold was also unrelated to the fold of PcECN (Fig. 1C). Within a single ECN subunit, four heme molecules are surrounded by a few sparsely distributed α-helices. At the same time, the C-terminal region (residue 190-250) forms an extended “arm-like” architecture projecting out from the body of the subunit, composed of multiple antiparallel β-stands (Fig. 2C).

The stacking arrangements of heme porphyrin rings in AvECN are similar to those in PcECN and both the OmcS and OmcE filaments from G. sulfurreducens, in terms of edge-to-edge distances (Fig. 2D) and alternately antiparallel and T-shaped stacking patterns. The most striking feature in AvECN relates to how heme molecules are coordinated: three out of four hemes in every AvECN subunit are coordinated by residues from two adjacent subunits: heme 1 is coordinated by H50 of the same subunit and H165 of the subunit above; heme 2 is coordinated by H85 of the same subunit and H32 of the subunit beneath; heme 4 is coordinated by H189 of the same subunit and H108 of the subunit beneath (Fig. 2E). This extensive heme-sharing is not observed in bacterial ECNs and may be a strategy to increase filament stability and facilitate electron transport between repeating cytochrome subunits. Another factor contributing to AvECN thermal stability could be N-linked glycosylation which is even more abundant than in PcECN (Supplementary Fig. 4).

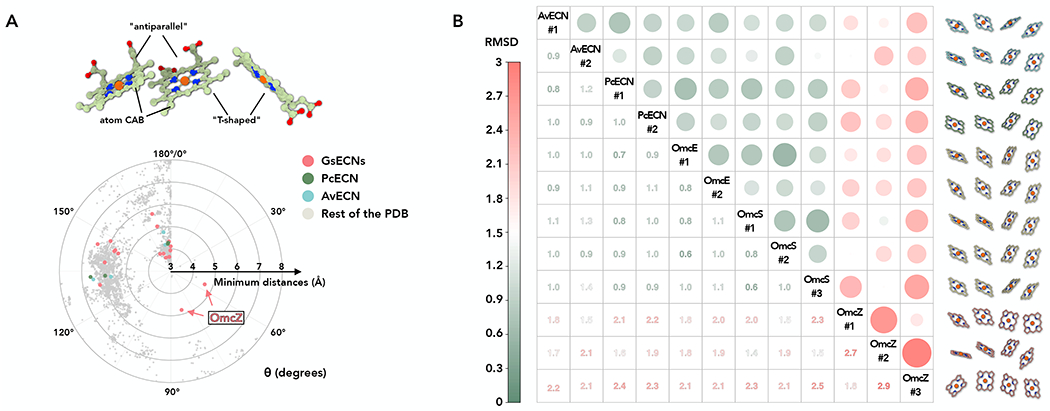

Conserved heme stacking path in ECNs

It has been shown that there are preferred heme-heme pairing motifs used in proteins capable of efficient electron transfer.16,17 Specifically, two major clusters were observed for the rotation angles and minimum edge-to-edge distances between porphyrin rings from two heme molecules: (1) ~3-5 Å distance and ~170-180° rotation, corresponding to the antiparallel heme pair; (2) ~4-6 Å distance and ~110-150° rotation, corresponding to the “T-shape” heme pair (Fig. 3A). The antiparallel heme pairs were often called “stacked” hemes in the past.20,30 Here we refer to them as antiparallel heme pairs to describe their packing nature more accurately. For instance, heme-pairs in the well-studied Shewanella small tetraheme cytochrome31 and flavocytochrome c332 all fall into the preferred clusters. All possible porphyrin pairs in AvECN and PcECN fall into those two clusters, and in addition, the two types of heme stackings always occur alternately, that is, antiparallel -> T-shape -> antiparallel -> T-shape … This observation also applies to G. sulfurreducens OmcS and OmcE filaments, but is not entirely true in the OmcZ filament as it has solvent accessible heme molecules that break this stacking pattern (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3. Conserved heme stacking in ECNs.

(A) The heme-heme orientation plot. One heme can be aligned to the adjacent heme by a rotation and a translation. Only 25 non-hydrogen atoms in the porphyrin ring are used in the alignment. The heme (ID: HEC or HEM) pairs in all PDB structures were analyzed. Example of “antiparallel” and “T-shaped” pairs are shown. The minimum distances refer to the smallest distance between two porphyrin rings, regardless of the atom type. The angle θ was determined from the alignment rotation matrix between heme pairs. For example, θ = 0° means two porphyrin rings are perfectly parallel, while θ = 180° means two porphyrin rings are perfectly antiparallel (flipped). All porphyrin ring pairs with a minimum distance less than or equal to 8 Å are shown. The porphyrin ring pairs in Geobacter, Pyrobaculum, and Archaeoglobus ECNs are shown in red, green, and cyan, respectively.

(B) All-against-all comparison of all four-heme arrays in structures of ECNs. All possible four-heme arrays with the heme arrangements of “antiparallel” -> “T-shaped” -> “antiparallel” were extracted from structures of ECNs for this comparison. Tetra-heme ECNs, such as PcECN, AvECN, and OmcE, possess two of such four-heme arrays along the filament structure. On the other hand, hexa-heme ECN OmcS has three different arrays. The Octa-heme ECN OmcZ, the only leaky ECN structure, also has three arrays due to a solvent-accessible heme adopting a quite different pose breaking the conserved heme arrangements. The matrix is based on the pairwise RMSD comparison of 20 atoms between two arrays (five atoms per heme, including the iron and four surrounding nitrogen atoms). The resulting RMSD is shown in color, as indicated in the left bar. Extreme RMSD values are highlighted by larger dot sizes to emphasize very similar and different heme arrangements.

We then asked whether ECNs have evolved an optimized heme stacking path along the filament for long-range electron transfer, despite having no protein fold similarity. We compared all possible four-heme arrays, with the first two hemes being an antiparallel pair, in AvECN, PcECN, OmcS, OmcE, and OmcZ. To mainly focus on the heme location and ignore differences introduced by heme in-plane rotation, only five atoms per heme molecule, the iron and four N- atoms surrounding it, were used for this analysis. Strikingly, all such arrays, except those in OmcZ, are remarkably similar, with an RMSD smaller than 1.1 Å (Fig. 3B). This small RMSD is almost at the level of experimental error in the determination of the atomic coordinates being used in the comparisons. These results suggest that when an ECN wraps a solvent inaccessible electron transport path, there is an optimized mode of heme stacking, with alternating antiparallel and T-shaped arrangements. In contrast, for an ECN that includes solvent-accessible hemes, OmcZ, a different pattern of hemes is present.

Evolution has optimized the four-heme array present in various protein families

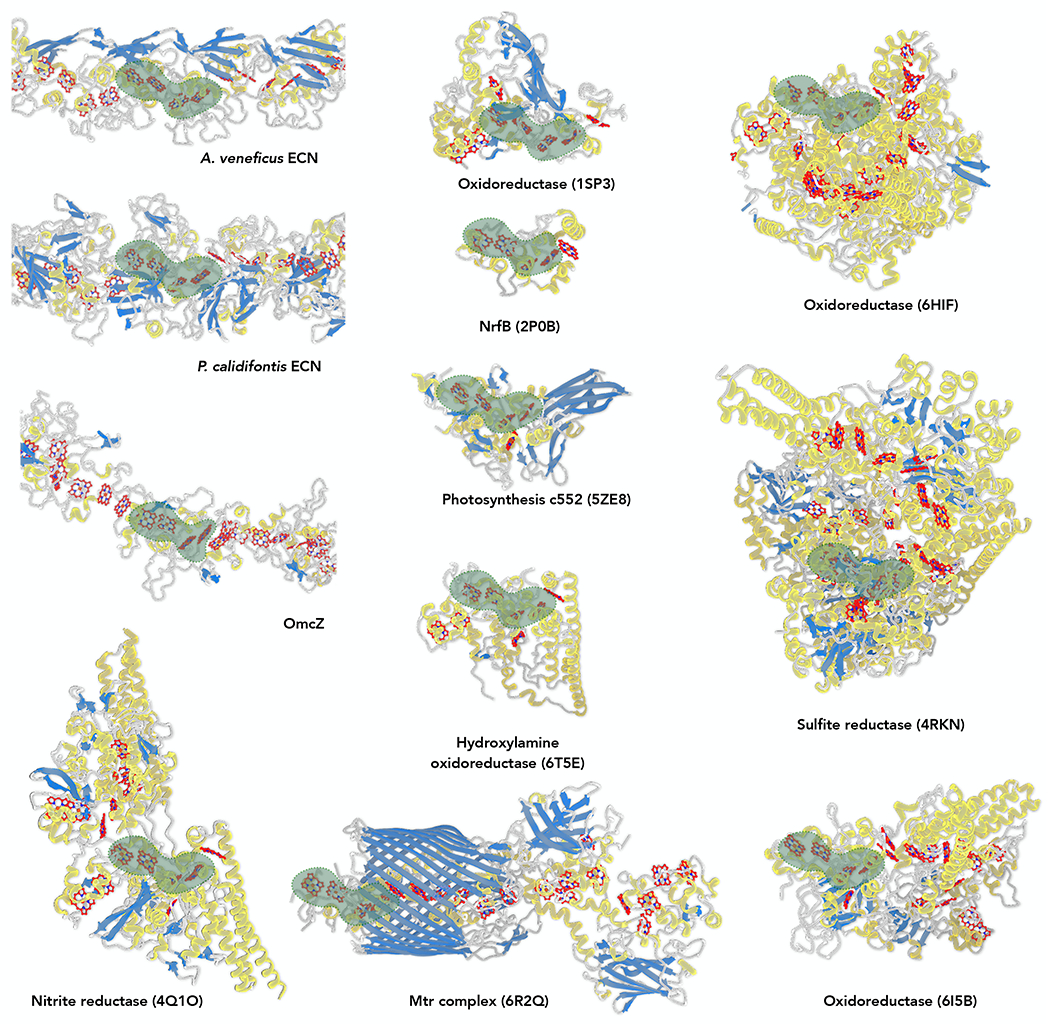

Heme stacking patterns have been suggested to be similar in diverse protein families.33 Since the four-heme arrays are conserved among fully insulated ECNs (those with a solvent-exposed heme only at filament ends) and those ECNs transfer electrons on a micron scale, we wondered whether this type of four-heme array can be found in other protein families that transfer electrons over shorter distances. Therefore, we analyzed all multi-heme (both heme and heme c) entries in the PDB, identified all four-heme arrays similar to those seen in ECNs, and searched for the four-heme array in each PDB entry with the smallest RMSD compared to the input template (AvECN). To our surprise, among all the identified four-heme arrays, OmcZ has the largest RMSD of 1.7 Å, and all other four-heme arrays have an RMSD between 0.6-1.1 Å compared with AvECN. The results are similar if different four-heme arrays found in ECNs (such as OmcE or OmcS) are used as the reference. All those cytochromes detected were then analyzed by the DALI server,24 and only one example in each protein fold is displayed in Fig. 4. Despite no recognizable fold similarity and functional divergence, including fully insulated ECNs, a leaky ECN (OmcZ), nitrite reductase, sulfite reductase, NrfB, photosynthetic cytochrome c552, hydroxylamine oxidoreductase, Mtr complex, and three types of oxidoreductases, this four-heme array pattern is ubiquitous in nature, suggesting this is an evolutionarily optimized heme-orientation for efficient electron transfer.

Figure 4. Similar four-heme array present in various protein families.

Protein structures are colored by their secondary structures: α-helices in yellow; β-strands in blue; loops in grey. Heme molecules (heme and heme c) are colored in red. The identified four-heme arrays with minimum RMSD within the structure are enveloped in green.

ECN homologs are widespread in Archaea

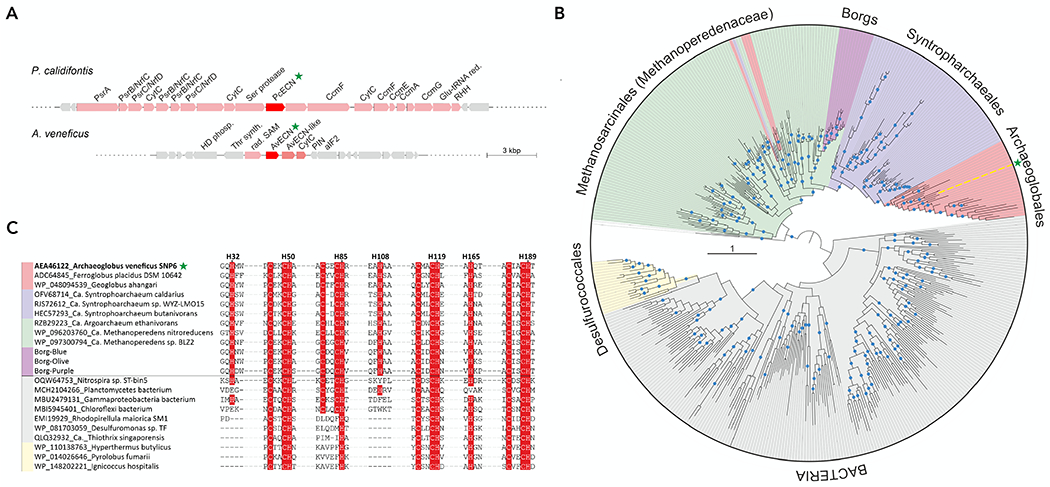

We next examined the genomic loci containing the ECN-encoding genes in P. calidifontis and A. veneficus. This analysis was particularly revealing for P. calidifontis, where the ECN gene is interspersed between apparent operons for respiratory nitrate reductase and cytochrome c biogenesis system, Ccm (Fig. 5A). The nitrate reductase is a multicomponent integral membrane protein complex responsible for reduction of nitrite to ammonia, an energy-generating process supporting the growth of many hyperthermophiles, including Pyrobaculum, in extreme volcanic or geothermically active environments, such as terrestrial hot springs and deep-sea hydrothermal vents.34,35 In contrast, the Ccm system is responsible for translocation of heme across the membrane and its covalent ligation to an apo-cytochrome c.36 Thus, based on its genomic neighborhood, it is likely that PcECN participates in nitrate reduction and that its maturation depends on the Ccm machinery. Indeed, P. calidifontis has been shown to use nitrate as a final electron acceptor.20

Figure 5. Diversity and distribution of archaeal ECN homologs.

(A) ECN-encoding genomic loci in P. calidifontis and A. veneficus. ECN genes and functionally related genes are shown as red and pink arrows respectively, whereas unrelated genes are shown in grey. Abbreviations: PrsA, Fe-S, 4Fe-4S cofactor-containing component of the polysulfide/nitrite reductase; PsrB/NrfC, 4Fe-4S cofactor-containing component of the polysulfide/nitrite reductase; PsrC/NrfD, polysulfide/nitrite reductase membrane component; CytC, cytochrome c family protein; CcmAEFG, cytochrome c biogenesis system components A, E, F and G; RHH, ribbon-helix-helix DNA-binding protein; Glu-tRNA red, glutamyl-tRNA reductase; HD phosph, HD-superfamily phosphohydrolase; Thr synth, threonine synthase; rad. SAM, radical SAM superfamily enzyme; PIN, PIN-domain nuclease; aIF2, archaeal translation initiation factor 2.

(B), Mid-point rooted maximum likelihood phylogeny of AvECN homologs. Tree branches are colored according to the organism taxonomy, with the taxon names indicated next to the corresponding clades. Note the horizontal transfers from Methanosarcinales to Archaeoglobales and Syntrophoarchaeales are shown as pink and magenta inserts within the green clade, respectively. The position of AvECN is indicated by yellow line and green star. Blue circles denote aLRT branch supports higher than 90%. The scale bar represents the number of substitutions per site.

(C) Sequence motifs conserved in AvECN homologs. Archaeal groups are represented by 3 sequences each, whereas bacterial homologs are represented by 7 sequences. The name of each sequence includes GenBank accession number followed by a species name. In the case of Borgs, the sequences were downloaded from the supplementary information of.39 Conserved His and Cys residues are highlighted on red background. The numbered His residues shown above the alignment correspond to the AvECN sequence. The horizontal line separates sequences belonging to the two major clades identified in the phylogeny shown in panel B.

Notably, PcECN has a predicted C-terminal transmembrane domain (residues 361-380), which was not present in our cryo-EM map, suggesting it has been proteolytically processed prior to ECN assembly. The protein region upstream of the transmembrane domain does not carry canonical archaeosortase or exosortase recognition motifs.37 However, immediately upstream of the PcECN gene, there is a gene encoding a putative serine protease, which is predicted to have an N-terminal Sec signal sequence and a C-terminal membrane anchor domain (Fig. 5A), suggesting that the catalytic protease domain is located on the outside of the cell. Thus, it is likely that the C-terminal transmembrane domain of PcECN is processed by the adjacently encoded serine protease, following the incorporation of the heme molecule and maturation of the PcECN subunit.

Compared to PcECN, the genomic environment of the AvECN gene was less informative (Fig. 5A). The gene is followed by a second copy of the AvECN-like gene (Arcve_0080; the corresponding proteins are 52% identical) and a gene encoding another multi-heme protein (Arcve_0079). However, the three-gene cassette is embedded among genes without apparent involvement in energy generating processes or cytochrome maturation (e.g., threonine synthase or translation initiation factor 2).

To explore the phyletic distribution of the two archaeal ECN homologs, we performed PSI-BLAST searches queried with the corresponding sequences against the non-redundant GenBank protein sequence database. Whereas the homologs of PcECN were not detected outside of the archaeal order Desulfurococcales (genera Pyrobaculum and Pyrodictium), AvECN were distributed more broadly (Fig. 5B). In particular, AvECN homologs are widespread not only among other hyperthermophilic members of order Archaeoglobales, but also among alkane degrading archaea of the order Syntrophoarchaeales and methane oxidizers of the family Methanoperedenaceae (also known as ANME-2d; order Methanosarcinales).38 Furthermore, AvECN homologs are conserved in multiple Borgs, a group of recently discovered extremely large (up to 1 Mbp) linear megaplasmids associated with methane-oxidizing Methanoperedens archaea.39 Each Borg element contained two tandemly encoded ECN copies, similar to A. veneficus (Fig. 5A). Notably, it has been suggested that Borgs provide Methanoperedens archaea access to genes encoding proteins involved in redox reactions and energy conservation and thereby assist in modulating greenhouse gas emissions.39 We hypothesize that AvECN homologs play an important role in these processes by mediating long-range electron transfers. More distant homologs of AvECN are also present in diverse bacteria and hyperthermophilic archaea of the order Desulfurococcales (Fig. 5B). In maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis, AvECN homologs split into two major clades, with one clade including the archaeal proteins from the Archaeoglobales, Syntrophoarchaeales and Methanoperedenaceae, including Borgs, and the other clade comprising bacterial and Desulfurococcales homologs. Notably, the branching pattern of the tree suggests that Archaeoglobales ECNs, including AvECN, have evolved from the Syntrophoarchaeales, which in turn have emerged from Methanoperedenaceae. Similarly, ECN homologs of Borgs have evidently been acquired from the Methanoperedenaceae host on a single occasion, followed by duplication and diversification within Borgs. Several more recent horizontal gene transfer events from Methanoperedenaceae to Archaeoglobales and Syntrophoarchaeales were also detected (Fig. 5B, Supplementary Data1). In the second clade, Desulfurococcales subclade emerges from within the diversity of bacterial homologs, suggesting a bacteria-to-archaea horizontal gene transfer.

To analyze whether AvECN homologs in other archaea and bacteria are likely to form ECNs, we assessed the conservation of the amino acid motifs involved in heme attachment and coordination (Fig. 5C). Whereas in Archaeoglobales, Syntrophoarchaeales and Methanoperedenaceae, as well as Borgs, all motifs were well conserved, in bacterial and Desulfurococcales homologs, the motifs containing AvECN heme-coordinating H32 and H108 were largely missing, suggesting functional divergence. The conservation of the heme coordinating motifs in AvECN homologs of Methanoperedens, Syntrophoarchaeales and Borgs strongly suggests that these ecologically important archaea will produce structurally similar ECNs.

Evolutionary link between AvECN-like proteins and c552-family cytochromes

Although structure-based searches queried with ECN subunits failed to identity structural homologs, sensitive profile-profile searches queried with AvECN yielded a significant, albeit partial, hit to a c552-family protein from a purple sulfur photosynthetic bacterium Thermochromatium tepidum.40 Similarly, when the AvECN homolog from a Planctomycetes bacterium was used as a query, c552 from T. tepidum was again identified as the best hit (HHsearch probability of 100%; Supplementary Fig. 5A–B). To further explore this potential relationship, we manually compared the structures of AvECN and c552 cytochrome (PDB: 5ZE8). When AvECN was aligned to c552 by four shared heme molecules, a set of α-helices in AvECN overlapped quite well with part of the N-terminal domain (Pfam-13435) of c552 (Supplementary Fig. 5C–E), further supporting an evolutionary relationship between AvECN and c552, and suggesting that the two protein families have shared a common ancestor.

Discussion

Starting from a bioinformatics approach aimed at finding potential extracellular cytochrome filaments in archaea, we identified three culturable organisms that appeared to be good candidates for having such filaments. We identified ECNs in two of these archaeal organisms, P. calidifontis and A. veneficus, and determined their atomic structures. Does this mean that ECNs are never produced by the third organism, M. tindarius? We think not, as it is quite possible that such filaments might be expressed by M. tindarius under different cultivation conditions. On the other hand, is it possible that P. calidifontis and A. veneficus are the only two archaeal species expressing such extracellular cytochrome filaments? This seems highly unlikely and our results strongly suggest that such ECNs are ubiquitous in both bacteria and archaea that rely on long-range electron transfer for metabolism. This is consistent with the identification of numerous archaeal AvECN homologs in Archaeoglobales, Syntrophoarchaeales, and Methanoperedenaceae. Our results also establish that the extracellular cytochrome filaments that have been found in G. sulfurreducens are not unique.

Unlike G. sulfurreducens cytochrome filaments that lack substantial amounts of secondary structure and contain ~80% loops, PcECN and AvECN have significantly higher percentages of secondary structures at 33% and 44%, respectively. Generally, a low percentage of secondary structure is a common feature seen in electron-transporting multi-heme cytochromes,41 mainly due to the pressure of evolutionary selection focused on closely stacked heme arrangements for efficient electron transfer, rather than on a conserved protein fold. Interestingly, despite a relatively higher percentage of secondary structure, a similar protein fold for either PcECN or AvECN cannot be identified among known protein structures using conventional methods, such as DALI, suggesting that ECN structures are still very sparsely sampled. Nevertheless, sensitive profile-profile HMM comparisons pointed towards an evolutionary relationship between AvECN and c552-family proteins, suggesting that at least some ECNs have evolved from non-filamentous multi-heme cytochrome proteins.

Despite no fold similarity among the five structurally characterized ECNs, the heme path in insulated nanowires, which includes all existing structures of ECNs except for OmcZ, share a strikingly similar pattern, with alternating antiparallel and T-shaped arrangements. While we have not been able to directly measure the conductivity of the PcECN and AvECN (see Limitations of the Study), given the quaternary structure of the ECNs and the highly conserved heme packing, it is very likely that the two archaeal ECNs function in long-distance electron transfer with a similar conductivity as the OmcS and OmcE filaments. We also think that the existence of these filaments must be due to a strong selection given the biosynthetic cost, and the extracellular bacterial flagellar filament provides a good example. In stirred liquid culture, where motility conveys no advantage, bacterial colonies lose the flagellar filament within only ten days as a result of mutations in any of the large number of flagellar genes.42 The conclusion was that mutants that fail to synthesize flagellin have a growth rate advantage of ~2% due to the high biosynthetic cost of producing flagellin when it is not needed. Similarly, we would expect that there would be a large metabolic penalty for producing extracellular cytochrome polymers that can be microns long in the absence of an important role played by these polymers in long-range electron transport.

When looking at four-heme arrays, the RMSD among all insulated ECNs is less than 1.1 Å. Similar four-heme arrays can also be identified in multi-heme enzymes, implying that this arrangement is an optimal path for efficient electron transfer. This leads to another question: do the hemes always pack in antiparallel and T-shape alternatively in insulated ECNs? Conceivably, from a protein folding perspective, having more than two antiparallel c-type hemes could be rather challenging since each heme needs to be coordinated by two histidines and two thioether linkages from two cysteines. However, nothing seems to prevent a multi-heme cytochrome from having continuous T-shape packing of hemes, and it has recently been suggested that the electron transfer rate between T-shape hemes is similar to or less than an order of magnitude faster than between antiparallel ones.43–45 The current absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, and more structures of insulated ECNs are needed to address whether cytochrome nanowires containing a continuous T-shape packing of hemes exist.

In Geobacter, expression of ECNs (OmcS/E/Z) is tightly linked to a type IV pilus made of two chains, PilA-N and PilA-C. The pilin was proposed to form a periplasmic endopilus,11 formerly called a pseudopilus, possibly functioning as a pump to aid the export of cytochrome filaments through a Type 2 Secretion System (T2SS).18 However, it is unclear in archaea how ECNs are assembled and secreted to the extracellular space. Interestingly, the presence of the N-terminal signal sequences and signal peptidase cleavage sites suggests that pre-ECN subunits are externalized through the Sec pathway to the cell exterior. In the case of PcECN, the proximity of the gene to the cytochrome c biogenesis and maturation system, Ccm, further suggests that following the externalization, the pre-ECN subunits undergo maturation and heme loading by the Ccm machinery. These observations provide testable hypotheses for future research. The genetic neighborhood analysis suggests that PcECN is involved respiratory nitrate reduction, consistent with the evidence that P. calidifontis can use nitrate as a final electron acceptor.20 The terminal acceptors of long-range electron transfer through AvECNs remain unclear. However, in the case of Methanoperedenaceae, it has been shown that for methane oxidation these archaea can transfer electrons extracellularly to a number of soluble and insoluble electron acceptors, including sulfate, nitrate, and metal oxides.46 The conservation and broad distribution of AvECN homologs in Methanoperedens, Syntrophoarchaeales and Borgs suggest that long-range electron transfer associated with methane oxidation occurs through structurally similar ECNs, contributing to modulation of greenhouse gas emissions.

Recent advances in cryo-EM have made it possible to directly and routinely determine a protein filament’s atomic structure, allowing unambiguous protein identification.11 It is thus not surprising that application of these methods to both bacteria and archaea continue to show at an increasing rate the existence of previously uncharacterized, functionally diverse extracellular filaments.21,47 We therefore expect that further studies of bacteria and archaea will reveal the existence and structure of many more ECNs. Given the enormous potential for such nanowires in applications such as biomedical devices, nanoelectronics, and bioenergy, we expect that further basic research in this area will be fruitful.

Limitations of the Study

One of the limitations of this study is the lack of conductivity measurements for the archaeal extracellular cytochrome filaments. However, there are enormous experimental challenges in this regard. Most conductivity measurements are performed on air-dried samples.48–50 The implicit assumption must be that the atomic structure of these filaments is unchanged from solution. But we know from more than 80 years of structural biology that this cannot be the case,51 and protein structure is only maintained in a fully hydrated state, which is either in solution or in a crystal in solution. There are two “competing” models for conductivity in extracellular filaments. One is that it arises from the stacking of aromatic residues in T4P, the other is that it is due to stacked hemes. In both, a particular atomic structure needs to be precisely maintained to support such conductivity. Thus, air-drying of T4P or cytochrome filaments would unavoidably lead to the loss of atomic basis for conductivity. Consequently, there is little physiological relevance to the conductivity measured from denatured air-dried filaments.

There are additional limitations with existing techniques for measuring conductivity. For all insulated ECNs, hemes are only exposed at two ends of the filaments. Therefore, for a meaningful measurement, the electrodes would need to be perfectly aligned to physically touch exposed hemes at both ends of a filament, which is nearly impossible. Recently, OmcZ filaments have been stated to be 1000x fold more conductive than OmcS,48 despite their similar heme-heme packing. We hypothesized that the branched hemes in OmcZ, with a solvent-exposed heme in each subunit, accounted for the higher measured conductivity.17 Another problem in such conductivity measurements is that one does not really know what filaments are being measured. For example, Pyrobaculum produces at least three other extracellular filaments in addition to the cytochrome polymer. The atomic structures of two of them are already known21,52 and those filaments would be indistinguishable from cytochrome filaments under AFM, a technique used for the conductivity measurements. It is also apparent that DNA can be found in extracellular preparations of cytochrome filaments.16,18 Interestingly, extracellular DNA has previously been reported to be conductive,53 so even the most careful attempts to measure conductivity of extracellular filaments may be attributed to the DNA contamination.

In summary, current technology does not exist for reliably measuring the conductivity of individual fully hydrated filaments of known composition. We believe that the development of such technology will be important.

STAR Methods

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Fengbin Wang, jerrywang@uab.edu

Materials availability

This study did not generate any new unique reagents.

Data and Code Availability

Protein models built from cryo-EM maps have been deposited at Protein Data Bank and are publicly available as of the date of publication. The corresponding cryo-EM maps have been deposited at the Electron Microscopy Data Bank. The Entry IDs are listed in the key resources table. Microscopy raw data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Tryptone | Gibco | Cat #: 211705 |

| Yeast extract | Gibco | Cat #: 212750 |

| Phosphotungstic acid (PTA) | Electron Microscopy Sciences | Cat #: 19502-1 |

| Uranyl acetate solution | Electron Microscopy Sciences | Cat #: 22400-2 |

| Sodium thiosulfate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: 217263 |

| Sodium chloride | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: S9888 |

| Potassium chloride | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: P9333 |

| Magnesium chloride | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: M8266 |

| Ammonium chloride | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: 326372 |

| Calcium chloride | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: C4901 |

| Potassium phosphate dibasic | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: P3786 |

| Ammonium iron(II) sulfate hexahydrate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: 203505 |

| Resazurin sodium salt | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: R7017 |

| Sodium bicarbonate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: S6014 |

| Sodium sulfite | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: S0505 |

| Sodium acetate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: S2886 |

| Sodium sulfide | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: 431648 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| G. sulfurreducens OmcS cryo-EM model | Wang et al.14 | PDB 6EF8 |

| G. sulfurreducens OmcE cryo-EM model | Wang et al.16 | PDB 7TFS |

| G. sulfurreducens OmcZ cryo-EM model | Wang et al.17 | PDB 8D9M |

| G. sulfurreducens type IV pilus cryo-EM model | Wang et al.16 | PDB 7TGG |

| T. tepidum c552-family protein | Chen et al.40 | PDB 5ZE8 |

| T. nitratireducens nitrite reductase | Lazarenko et al. | PDB 4Q1O |

| S. oneidensis oxidoreductase | Mowat et al.54 | PDB 1SP3 |

| E. coli NrfB | Clarke et al.55 | PDB 2P0B |

| B. fulgida hydroxylamine oxidoreductase | Akram et al.56 | PDB 6T5E |

| S. baltica Mtr complex | Edwards et al.41 | PDB 6R2Q |

| K. stuttgartiensis hydrazine dehydrogenase | Akram et al.57 | PDB 6HIF |

| W. succinogenes sulfite reductase | Hermann et al.58 | PDB 4RKN |

| T. potens oxidoreductase | Costa et al.59 | PDB 6I5B |

| P. calidifontis ECN, cryo-EM map | This paper | EMD-27911 |

| P. calidifontis ECN, atomic model | This paper | PDB 8E5F |

| A. veneficus ECN, cryo-EM map | This paper | EMD-27912 |

| A. veneficus ECN, atomic model | This paper | PDB 8E5G |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Pyrobaculum calidifontis | Amo et al.20 | DSM 21063 |

| Archaeoglobus veneficus | Huber et al.29 | DSM 11195 |

| Methanolobus tindarius | König et al.60 | DSM 2278 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| cryoSPARC | Punjani et al.61 | https://cryosparc.com |

| ChimeraX | Pettersen et al.62 | https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimerax |

| Phenix | Afonine et al.63 | https://phenix-online.org |

| Coot | Emsley et al.64 | https://www2.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/personal/pemsley/coot |

| MolProbity | Williams et al.65 | http://molprobity.biochem.duke.edu |

| AlphaFold2 | Jumper et al.22 | https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk |

| DeepTracer | Pfab et al.66 | https://deeptracer.uw.edu/ |

| DeepTracer-ID | Chang et al.67 | https://deeptracer.uw.edu/deeptracerid-new-job |

| Foldseek | van Kempen et al.25 | https://search.foldseek.com/search |

| DALI | Holm et al.24 | http://ekhidna2.biocenter.helsinki.fi/dali/ |

| IHRSR-spider | Egelman et al.68 | https://joachimfranklab.org/research/software/ |

This paper didn’t generate any original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND STUDY PARTICIPANT DETAILS

Organism/Strain: P. calidifontis growth condition

Pyrobaculum calidifontis DSM 21063 cells were purchased from the DSMZ culture collection and grown in 1090 medium (0.1% yeast extract, 1.0% tryptone, 0.3% sodium thiosulfate, pH 7) at 90 °C without agitation. Preculture (30 mL) was started from a 200 μL cryo-stock, grown for 2 d and then diluted into 200 mL of fresh medium. When OD600 reached ~0.2, the cells were collected by centrifugation (Sorval SLA1500 rotor, 7,000 rpm, 10 min, 20 °C).

Organism/Strain: A. veneficus growth condition

Archaeoglobus veneficus DSM 11195 cells were purchased from the DSMZ culture collection. Three A. veneficus cultures (40 mL each) were grown at 75°C in 100 mL serum bottles under strict anaerobic conditions in DSMZ medium 796, as described previously.29

Organism/Strain: M. tindarius growth condition

Methanolobus tindarius DSM 2278 was purchased from the DSMZ culture collection. M. tindarius cells (40 mL) were grown at room temperature in a 100 mL serum bottle under strict anaerobic conditions in DSMZ medium 233, as described previously.60

METHOD DETAILS

P. calidifontis filament preparation

The resultant pellet was resuspended in 4 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer, and the cell suspension was vortexed for 15 min to shear off the extracellular filaments. The cells were removed by centrifugation (Eppendorf F-35-6-30 rotor, 7,830 rpm, 20 min, 20 °C). The supernatant was collected and the filaments were pelleted by ultracentrifugation (Beckman SW60Ti rotor, 38,000 rpm, 2 h, 15 °C). After the run, the supernatant was removed, and the pellet was resuspended in 200 μL of PBS.

A. veneficus filament preparation

After three days of incubation, cultures were mixed and the majority of cells were removed by centrifugation (Eppendorf F-35-6-30 rotor, 7,830 rpm, 20 min, 20 °C). The supernatant was recovered, and filaments were collected and concentrated by ultracentrifugation (158,728 × g, 3 h, 15 °C, Beckman 45 Ti rotor). After the run, the supernatant was carefully removed, and the pellet was resuspended in 300 μL of PBS.

M. tindarius filament preparation

After four days of incubation, cells were removed by centrifugation (Eppendorf F-35-6-30 rotor, 7,830 rpm, 20 min, 20 °C). The supernatant was recovered and filaments were collected and concentrated by ultracentrifugation (158,728 × g, 3 h, 15 °C, Beckman 45 Ti rotor). After the run, the supernatant was carefully removed, and the pellet was resuspended in 300 μL of PBS.

Cryo-EM conditions and image processing

The cell appendage sample (ca. 3.5-4.5 μl) was applied to glow-discharged lacey carbon grids and then plunge frozen using an EM GP Plunge Freezer (Leica). The cryo-EMs were collected on a 300 keV Titan Krios with a K3 camera (University of Virginia) at 1.08 Å/pixel and a total dose of ca. 50 e/Å2. First, patch motion corrections and CTF estimations were done in cryoSPARC.61,69,70 Next, particles were auto-picked by “Filament Tracer”. All auto-picked particles were subsequently 2D classified with multiple rounds, and all particles in bad 2D averages were removed. After this, the P. calidifontis dataset had 101,864 particles left with a shift of 36 pixels between adjacent boxes, while the A. veneficus dataset had 92,602 particles left with the same 36-pixel shift. Next, the possible helical symmetries were calculated from an averaged power spectrum for each filament species generated from the raw particles. There is only one possibility for helical symmetry for both filaments, and the volume hand was determined by the hand of α-helices in the map.68,71 After that, 3D reconstruction was performed using “Helical Refinement” first, and then using “Non-uniform Refinement”. The resolution of each reconstruction was estimated by Map:Map FSC, Model:Map FSC, and d99.72 The final volumes were then sharpened with a negative B-factor automatically estimated in cryoSPARC, and the statistics are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Model building of P. calidifontis and A. veneficus ECNs

The density corresponding to a single P. calidifontis ECN subunit was segmented from the experimental cryo-EM density using Chimera.73 Without using prior knowledge, placing heme molecules into the cryo-EM map at this resolution is challenging, especially while ligands are not included in AlphaFold predictions. Therefore, to better refine heme interacting areas at this resolution, bond/angle restraints for the heme molecule itself, His-Fe, and Cys-heme thioester bonds were restricted based on the geometries obtained in high-resolution crystal structures such as NrfB 55 (PDB 2P0B) and NrfHA 74 (PDB 2J7A). Similar refinement strategies have been used for G. sulfurreducens ECNs.14,16,17 MolProbity65 was used to evaluate the quality of the filament model. Similar to the model building of P. calidifontis cytochrome filaments, the single subunit map of A. veneficus was segmented. The subsequent 3D reconstructions and refinement are similar to the P. calidifontis case. The refinement statistics of both PcECN and AvECN are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Structural analysis of heme molecules in heme containing PDBs

All structural coordinates with heme ligand (HEC or/and HEM) were downloaded from the Protein Data Bank. All possible heme pairs were then filtered with a minimum distance less than or equal to 8 Å between two porphyrin rings, using the “contact” command in UCSF-ChimeraX.62 For each qualified pair, the rotation matrix between two hemes was generated in ChimeraX using the “align” command. The rotation angle Θ was then calculated from the rotation matrix with the following equation, where tr is the trace of the rotation matrix. For the four-heme array analysis, the RMSD value between different four-heme arrays were also generated in ChimeraX using the “align” command.

Homology searches and phylogenetic analysis

Homologs of PcECN and AvECN were collected by PSI-BLAST (5 iterations, inclusion E-value threshold of 1e-06) against non-redundant protein sequence database at NCBI. Due to large number of homologs, the highly similar bacterial sequences in the obtained dataset were then filtered to 50% identity over 80% of protein length using MMseq2.75 All sequences shorter than 200 aa and longer than 400 aa were purged to discard partial sequences and to avoid potential problems with sequence alignment. This dataset was supplemented with ECN homologs from Borgs, which were identified using AvECN as a query in BLASTP searches (default parameters) against the Borg proteomes obtained.39 Each of the following Borgs contained two AvECN homologs: Borg-Black, Borg-Blue, Borg-Brown, Borg-Olive, Borg-Orange and Borg-Purple. Multiple sequence alignment was built using MAFFT with the G-INS-1 option. The poorly conserved positions were removed using trimal with the gap threshold of 0.2.76 Maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis was performed using IQ-Tree v1.6.1277 with the best amino acid substitution model selected for the alignment being WAG+I+G4. Brach support was assessed using the nonparametric SH-aLRT test. The phylogeny was visualized using iTOL v6.78 Sensitive searches based on comparison of profile hidden Markov models (HMM) were performed using HHsearch from the HH-suite package v3.79 Signal peptides and signal peptidase I cleavage sequences were predicted using SignalP v6.23

Supplemental Figure titles and legends

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Atomic structures of extracellular cytochrome nanowires (ECNs) from archaea revealed.

Structurally unrelated bacterial and archaeal ECNs have the same heme stacking

ECN homologs are widespread in Archaea, including ANME-2, and Borg megaplasmids

Archaeoglobus veneficus ECN may have evolved from c552-family cytochromes

Acknowledgements

The cryo-EM imaging was done at the Molecular Electron Microscopy Core Facility at the University of Virginia, which is supported by the School of Medicine. This work was supported by NIH Grant GM122510 (E.H.E.) and GM138756 (F.W.). The work in the M.K. laboratory was supported by grants from I’Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR-20-CE20-009-02 and ANR-21-CE11-0001-01) and Ville de Paris (Emergence(s) project MEMREMA).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Reguera G (2018). Microbial nanowires and electroactive biofilms. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 94. 10.1093/femsec/fiy086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Light SH, Su L, Rivera-Lugo R, Cornejo JA, Louie A, Iavarone AT, Ajo-Franklin CM, and Portnoy DA (2018). A flavin-based extracellular electron transfer mechanism in diverse Gram-positive bacteria. Nature 562, 140–144. 10.1038/s41586-018-0498-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi L, Dong H, Reguera G, Beyenal H, Lu A, Liu J, Yu HQ, and Fredrickson JK (2016). Extracellular electron transfer mechanisms between microorganisms and minerals. Nat Rev Microbiol 14, 651–662. 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vargas M, Kashefi K, Blunt-Harris EL, and Lovley DR (1998). Microbiological evidence for Fe(III) reduction on early Earth. Nature 395, 65–67. 10.1038/25720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lovley DR (2017). Syntrophy Goes Electric: Direct Interspecies Electron Transfer. Annu Rev Microbiol 71, 643–664. 10.1146/annurev-micro-030117-020420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang W, and Lee DJ (2021). Direct interspecies electron transfer mechanism in enhanced methanogenesis: A mini-review. Bioresour Technol 330, 124980. 10.1016/j.biortech.2021.124980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGlynn SE, Chadwick GL, Kempes CP, and Orphan VJ (2015). Single cell activity reveals direct electron transfer in methanotrophic consortia. Nature 526, 531–535. 10.1038/nature15512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wegener G, Krukenberg V, Riedel D, Tegetmeyer HE, and Boetius A (2015). Intercellular wiring enables electron transfer between methanotrophic archaea and bacteria. Nature 526, 587–590. 10.1038/nature15733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ha PT, Lindemann SR, Shi L, Dohnalkova AC, Fredrickson JK, Madigan MT, and Beyenal H (2017). Syntrophic anaerobic photosynthesis via direct interspecies electron transfer. Nat Commun 8, 13924. 10.1038/ncomms13924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu X, Huang L, Rensing C, Ye J, Nealson KH, and Zhou S (2021). Syntrophic interspecies electron transfer drives carbon fixation and growth by Rhodopseudomonas palustris under dark, anoxic conditions. Sci Adv 7. 10.1126/sciadv.abh1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang F, Craig L, Liu X, Rensing C, and Egelman EH (2022). Microbial nanowires: type IV pili or cytochrome filaments? Trends in Microbiology in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Egelman EH (2016). The Current Revolution in Cryo-EM. Biophys J 110, 1008–1012. 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuhlbrandt W. (2014). Cryo-EM enters a new era. eLife 3, e03678. 10.7554/eLife.03678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang F, Gu Y, O’Brien JP, Yi SM, Yalcin SE, Srikanth V, Shen C, Vu D, Ing NL, Hochbaum AI, et al. (2019). Structure of Microbial Nanowires Reveals Stacked Hemes that Transport Electrons over Micrometers. Cell 177, 361–369 e310. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Filman DJ, Marino SF, Ward JE, Yang L, Mester Z, Bullitt E, Lovley DR, and Strauss M (2019). Cryo-EM reveals the structural basis of long-range electron transport in a cytochrome-based bacterial nanowire. Commun Biol 2, 219. 10.1038/s42003-019-0448-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang F, Mustafa K, Suciu V, Joshi K, Chan CH, Choi S, Su Z, Si D, Hochbaum AI, Egelman EH, and Bond DR (2022). Cryo-EM structure of an extracellular Geobacter OmcE cytochrome filament reveals tetrahaem packing. Nat Microbiol 7, 1291–1300. 10.1038/s41564-022-01159-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang F, Chan CH, Suciu V, Mustafa K, Ammend M, Si D, Hochbaum AI, Egelman EH, and Bond DR (2022). Structure of Geobacter OmcZ filaments suggests extracellular cytochrome polymers evolved independently multiple times. Elife 11. 10.7554/eLife.81551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gu Y, Srikanth V, Salazar-Morales AI, Jain R, O’Brien JP, Yi SM, Soni RK, Samatey FA, Yalcin SE, and Malvankar NS (2021). Structure of Geobacter pili reveals secretory rather than nanowire behaviour. Nature 597, 430–434. 10.1038/s41586-021-03857-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kletzin A, Heimerl T, Flechsler J, van Niftrik L, Rachel R, and Klingl A (2015). Cytochromes c in Archaea: distribution, maturation, cell architecture, and the special case of Ignicoccus hospitalis. Front Microbiol 6, 439. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amo T, Paje ML, Inagaki A, Ezaki S, Atomi H, and Imanaka T (2002). Pyrobaculum calidifontis sp. nov., a novel hyperthermophilic archaeon that grows in atmospheric air. Archaea 1, 113–121. 10.1155/2002/616075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang F, Cvirkaite-Krupovic V, Krupovic M, and Egelman EH (2022). Archaeal bundling pili of Pyrobaculum calidifontis reveal similarities between archaeal and bacterial biofilms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 119, e2207037119. 10.1073/pnas.2207037119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, Green T, Figurnov M, Ronneberger O, Tunyasuvunakool K, Bates R, Zidek A, Potapenko A, et al. (2021). Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589. 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teufel F, Almagro Armenteros JJ, Johansen AR, Gislason MH, Pihl SI, Tsirigos KD, Winther O, Brunak S, von Heijne G, and Nielsen H (2022). SignalP 6.0 predicts all five types of signal peptides using protein language models. Nat Biotechnol 40, 1023–1025. 10.1038/s41587-021-01156-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holm L. (2020). Using Dali for Protein Structure Comparison. Methods Mol Biol 2112, 29–42. 10.1007/978-1-0716-0270-6_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Kempen M, Kim SS, Tumescheit C, Mirdita M, Söding J, and Steinegger M (2022). Foldseek: fast and accurate protein structure search. bioRxiv, 2022.2002.2007.479398. 10.1101/2022.02.07.479398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang F, Baquero DP, Su Z, Beltran LC, Prangishvili D, Krupovic M, and Egelman EH (2020). The structures of two archaeal type IV pili illuminate evolutionary relationships. Nat Commun 11, 3424. 10.1038/s41467-020-17268-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang F, Cvirkaite-Krupovic V, Kreutzberger MAB, Su Z, de Oliveira GAP, Osinski T, Sherman N, DiMaio F, Wall JS, Prangishvili D, et al. (2019). An extensively glycosylated archaeal pilus survives extreme conditions. Nat Microbiol 4, 1401–1410. 10.1038/s41564-019-0458-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kreutzberger MAB, Sonani RR, Liu J, Chatterjee S, Wang F, Sebastian AL, Biswas P, Ewing C, Zheng W, Poly F, et al. (2022). Convergent evolution in the supercoiling of prokaryotic flagellar filaments. Cell 185, 3487–3500 e3414. 10.1016/j.cell.2022.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huber H, Jannasch H, Rachel R, Fuchs T, and Stetter KO (1997). Archaeoglobus veneficus sp. nov., a Novel Facultative Chemolithoautotrophic Hyperthermophilic Sulfite Reducer, Isolated from Abyssal Black Smokers. Systematic and Applied Microbiology 20, 374–380. 10.1016/S0723-2020(97)80005-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mowat CG, and Chapman SK (2005). Multi-heme cytochromes--new structures, new chemistry. Dalton Trans, 3381–3389. 10.1039/b505184c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leys D, Meyer TE, Tsapin AS, Nealson KH, Cusanovich MA, and Van Beeumen JJ (2002). Crystal structures at atomic resolution reveal the novel concept of “electron-harvesting” as a role for the small tetraheme cytochrome c. J Biol Chem 277, 35703–35711. 10.1074/jbc.M203866200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mowat CG, Moysey R, Miles CS, Leys D, Doherty MK, Taylor P, Walkinshaw MD, Reid GA, and Chapman SK (2001). Kinetic and crystallographic analysis of the key active site acid/base arginine in a soluble fumarate reductase. Biochemistry 40, 12292–12298. 10.1021/bi011360h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soares R, Costa NL, Paquete CM, Andreini C, and Louro RO (2022). A New Paradigm of Multiheme Cytochrome Evolution by Grafting and Pruning Protein Modules. Mol Biol Evol 39. 10.1093/molbev/msac139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jormakka M, Yokoyama K, Yano T, Tamakoshi M, Akimoto S, Shimamura T, Curmi P, and Iwata S (2008). Molecular mechanism of energy conservation in polysulfide respiration. Nat Struct Mol Biol 15, 730–737. 10.1038/nsmb.1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Afshar S, Johnson E, de Vries S, and Schroder I (2001). Properties of a thermostable nitrate reductase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrobaculum aerophilum. J Bacteriol 183, 5491–5495. 10.1128/JB.183.19.5491-5495.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanders C, Turkarslan S, Lee DW, and Daldal F (2010). Cytochrome c biogenesis: the Ccm system. Trends in Microbiology 18, 266–274. 10.1016/j.tim.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haft DH, Payne SH, and Selengut JD (2012). Archaeosortases and exosortases are widely distributed systems linking membrane transit with posttranslational modification. J Bacteriol 194, 36–48. 10.1128/JB.06026-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borrel G, Adam PS, McKay LJ, Chen LX, Sierra-Garcia IN, Sieber CMK, Letourneur Q, Ghozlane A, Andersen GL, Li WJ, et al. (2019). Wide diversity of methane and short-chain alkane metabolisms in uncultured archaea. Nat Microbiol 4, 603–613. 10.1038/s41564-019-0363-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al-Shayeb B, Schoelmerich MC, West-Roberts J, Valentin-Alvarado LE, Sachdeva R, Mullen S, Crits-Christoph A, Wilkins MJ, Williams KH, Doudna JA, and Banfield JF (2022). Borgs are giant genetic elements with potential to expand metabolic capacity. Nature 610, 731–736. 10.1038/s41586-022-05256-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen JH, Yu LJ, Boussac A, Wang-Otomo ZY, Kuang T, and Shen JR (2019). Properties and structure of a low-potential, penta-heme cytochrome c(552) from a thermophilic purple sulfur photosynthetic bacterium Thermochromatium tepidum. Photosynth Res 139, 281–293. 10.1007/s11120-018-0507-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edwards MJ, White GF, Butt JN, Richardson DJ, and Clarke TA (2020). The Crystal Structure of a Biological Insulated Transmembrane Molecular Wire. Cell 181, 665–673 e610. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Macnab RM (1992). Genetics and biogenesis of bacterial flagella. Annu Rev Genet 26, 131–158. 10.1146/annurev.ge.26.120192.001023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiang X, van Wonderen JH, Butt JN, Edwards MJ, Clarke TA, and Blumberger J (2020). Which Multi-Heme Protein Complex Transfers Electrons More Efficiently? Comparing MtrCAB from Shewanella with OmcS from Geobacter. J Phys Chem Lett 11, 9421–9425. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.0c02842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Wonderen JH, Hall CR, Jiang X, Adamczyk K, Carof A, Heisler I, Piper SEH, Clarke TA, Watmough NJ, Sazanovich IV, et al. (2019). Ultrafast Light-Driven Electron Transfer in a Ru(II)tris(bipyridine)-Labeled Multiheme Cytochrome. J Am Chem Soc 141, 15190–15200. 10.1021/jacs.9b06858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Wonderen JH, Adamczyk K, Wu X, Jiang X, Piper SEH, Hall CR, Edwards MJ, Clarke TA, Zhang H, Jeuken LJC, et al. (2021). Nanosecond heme-to-heme electron transfer rates in a multiheme cytochrome nanowire reported by a spectrally unique His/Met-ligated heme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118. 10.1073/pnas.2107939118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scheller S, Yu H, Chadwick GL, McGlynn SE, and Orphan VJ (2016). Artificial electron acceptors decouple archaeal methane oxidation from sulfate reduction. Science (New York, NY) 351, 703–707. 10.1126/science.aad7154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bohning J, Ghrayeb M, Pedebos C, Abbas DK, Khalid S, Chai L, and Bharat TAM (2022). Donor-strand exchange drives assembly of the TasA scaffold in Bacillus subtilis biofilms. Nat. Commun 13, 7082. 10.1038/s41467-022-34700-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yalcin SE, O’Brien JP, Gu Y, Reiss K, Yi SM, Jain R, Srikanth V, Dahl PJ, Huynh W, Vu D, et al. (2020). Electric field stimulates production of highly conductive microbial OmcZ nanowires. Nature Chemical Biology 16, 1136-+. 10.1038/s41589-020-0623-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dahl PJ, Yi SM, Gu Y, Acharya A, Shipps C, Neu J, O’Brien JP, Morzan UN, Chaudhuri S, Guberman-Pfeffer MJ, et al. (2022). A 300-fold conductivity increase in microbial cytochrome nanowires due to temperature-induced restructuring of hydrogen bonding networks. Sci Adv 8, eabm7193. 10.1126/sciadv.abm7193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Szmuc E, Walker DJF, Kireev D, Akinwande D, Lovley DR, Keitz B, and Ellington A (2023). Engineering Geobacter pili to produce metal:organic filaments. Biosens Bioelectron 222, 114993. 10.1016/j.bios.2022.114993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bernal J, Fankuchen I, and Perutz M (1938). An X-ray study of chymotrypsin and haemoglobin. Nature 141, 523–524. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beltran LC, Cvirkaite-Krupovic V, Miller J, Wang F, Kreutzberger MAB, Patkowski JB, Costa TRD, Schouten S, Levental I, Conticello VP, et al. (2023). Archaeal DNA-import apparatus is homologous to bacterial conjugation machinery. Nat Commun 14, 666. 10.1038/s41467-023-36349-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saunders SH, Tse ECM, Yates MD, Otero FJ, Trammell SA, Stemp EDA, Barton JK, Tender LM, and Newman DK (2020). Extracellular DNA Promotes Efficient Extracellular Electron Transfer by Pyocyanin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms. Cell 182, 919–932.e919. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mowat CG, Rothery E, Miles CS, McIver L, Doherty MK, Drewette K, Taylor P, Walkinshaw MD, Chapman SK, and Reid GA (2004). Octaheme tetrathionate reductase is a respiratory enzyme with novel heme ligation. Nat Struct Mol Biol 11, 1023–1024. 10.1038/nsmb827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clarke TA, Cole JA, Richardson DJ, and Hemmings AM (2007). The crystal structure of the pentahaem c-type cytochrome NrfB and characterization of its solution-state interaction with the pentahaem nitrite reductase NrfA. Biochem J 406, 19–30. 10.1042/BJ20070321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Akram M, Dietl A, Muller M, and Barends TRM (2021). Purification of the key enzyme complexes of the anammox pathway from DEMON sludge. Biopolymers 112, e23428. 10.1002/bip.23428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Akram M, Dietl A, Mersdorf U, Prinz S, Maalcke W, Keltjens J, Ferousi C, de Almeida NM, Reimann J, Kartal B, et al. (2019). A 192-heme electron transfer network in the hydrazine dehydrogenase complex. Sci Adv 5, eaav4310. 10.1126/sciadv.aav4310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hermann B, Kern M, La Pietra L, Simon J, and Einsle O (2015). The octahaem MccA is a haem c-copper sulfite reductase. Nature 520, 706–709. 10.1038/nature14109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Costa NL, Hermann B, Fourmond V, Faustino MM, Teixeira M, Einsle O, Paquete CM, and Louro RO (2019). How Thermophilic Gram-Positive Organisms Perform Extracellular Electron Transfer: Characterization of the Cell Surface Terminal Reductase OcwA. mBio 10. 10.1128/mBio.01210-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.König H, and Stetter KO (1982). Isolation and characterization of Methanolobus tindarius, sp. nov., a coccoid methanogen growing only on methanol and methylamines. Zentralblatt für Bakteriologie Mikrobiologie und Hygiene: I. Abt. Originale C: Allgemeine, angewandte und ökologische Mikrobiologie 3, 478–490. 10.1016/S0721-9571(82)80005-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Punjani A, Rubinstein JL, Fleet DJ, and Brubaker MA (2017). cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat Methods 14, 290–296. 10.1038/nmeth.4169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Meng EC, Couch GS, Croll TI, Morris JH, and Ferrin TE (2021). UCSF ChimeraX: Structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Sci 30, 70–82. 10.1002/pro.3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Afonine PV, Poon BK, Read RJ, Sobolev OV, Terwilliger TC, Urzhumtsev A, and Adams PD (2018). Real-space refinement in PHENIX for cryo-EM and crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 74, 531–544. 10.1107/S2059798318006551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Emsley P, and Cowtan K (2004). Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 60, 2126–2132. 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Williams CJ, Headd JJ, Moriarty NW, Prisant MG, Videau LL, Deis LN, Verma V, Keedy DA, Hintze BJ, Chen VB, et al. (2018). MolProbity: More and better reference data for improved all-atom structure validation. Protein Sci 27, 293–315. 10.1002/pro.3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pfab J, Phan NM, and Si D (2021). DeepTracer for fast de novo cryo-EM protein structure modeling and special studies on CoV-related complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118. 10.1073/pnas.2017525118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chang L, Wang F, Connolly K, Meng H, Su Z, Cvirkaite-Krupovic V, Krupovic M, Egelman EH, and Si D (2022). DeepTracer-ID: De novo protein identification from cryo-EM maps. Biophys J 121, 2840–2848. 10.1016/j.bpj.2022.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Egelman EH (2010). Reconstruction of helical filaments and tubes. Methods Enzymol 482, 167–183. 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)82006-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rohou A, and Grigorieff N (2015). CTFFIND4: Fast and accurate defocus estimation from electron micrographs. J Struct Biol 192, 216–221. 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zheng SQ, Palovcak E, Armache JP, Verba KA, Cheng Y, and Agard DA (2017). MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat Methods 14, 331–332. 10.1038/nmeth.4193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Egelman EH (2000). A robust algorithm for the reconstruction of helical filaments using single-particle methods. Ultramicroscopy 85, 225–234. 10.1016/s0304-3991(00)00062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Afonine PV, Klaholz BP, Moriarty NW, Poon BK, Sobolev OV, Terwilliger TC, Adams PD, and Urzhumtsev A (2018). New tools for the analysis and validation of cryo-EM maps and atomic models. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 74, 814–840. 10.1107/S2059798318009324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, and Ferrin TE (2004). UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem 25, 1605–1612. 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rodrigues ML, Oliveira TF, Pereira IA, and Archer M (2006). X-ray structure of the membrane-bound cytochrome c quinol dehydrogenase NrfH reveals novel haem coordination. EMBO J 25, 5951–5960. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Steinegger M, and Soding J (2017). MMseqs2 enables sensitive protein sequence searching for the analysis of massive data sets. Nat Biotechnol 35, 1026–1028. 10.1038/nbt.3988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Capella-Gutierrez S, Silla-Martinez JM, and Gabaldon T (2009). trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 25, 1972–1973. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Minh BQ, Schmidt HA, Chernomor O, Schrempf D, Woodhams MD, von Haeseler A, and Lanfear R (2020). IQ-TREE 2: New Models and Efficient Methods for Phylogenetic Inference in the Genomic Era. Mol Biol Evol 37, 1530–1534. 10.1093/molbev/msaa015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Letunic I, and Bork P (2021). Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res 49, W293–W296. 10.1093/nar/gkab301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Steinegger M, Meier M, Mirdita M, Vohringer H, Haunsberger SJ, and Soding J (2019). HH-suite3 for fast remote homology detection and deep protein annotation. BMC Bioinformatics 20, 473. 10.1186/s12859-019-3019-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Protein models built from cryo-EM maps have been deposited at Protein Data Bank and are publicly available as of the date of publication. The corresponding cryo-EM maps have been deposited at the Electron Microscopy Data Bank. The Entry IDs are listed in the key resources table. Microscopy raw data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Tryptone | Gibco | Cat #: 211705 |

| Yeast extract | Gibco | Cat #: 212750 |

| Phosphotungstic acid (PTA) | Electron Microscopy Sciences | Cat #: 19502-1 |

| Uranyl acetate solution | Electron Microscopy Sciences | Cat #: 22400-2 |

| Sodium thiosulfate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: 217263 |

| Sodium chloride | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: S9888 |

| Potassium chloride | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: P9333 |

| Magnesium chloride | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: M8266 |

| Ammonium chloride | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: 326372 |

| Calcium chloride | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: C4901 |

| Potassium phosphate dibasic | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: P3786 |

| Ammonium iron(II) sulfate hexahydrate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: 203505 |

| Resazurin sodium salt | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: R7017 |

| Sodium bicarbonate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: S6014 |

| Sodium sulfite | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: S0505 |

| Sodium acetate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: S2886 |

| Sodium sulfide | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #: 431648 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| G. sulfurreducens OmcS cryo-EM model | Wang et al.14 | PDB 6EF8 |

| G. sulfurreducens OmcE cryo-EM model | Wang et al.16 | PDB 7TFS |

| G. sulfurreducens OmcZ cryo-EM model | Wang et al.17 | PDB 8D9M |

| G. sulfurreducens type IV pilus cryo-EM model | Wang et al.16 | PDB 7TGG |