Abstract

There is conflicting evidence regarding whether females are more adversely affected after concussion than males. Further, recent research suggests that hormonal contraceptive (HC) use may affect symptom severity and duration post-concussion. The objective of this study was to examine the effects of sex and HC use on outcomes following concussion among collegiate varsity athletes. We hypothesized that females would have longer length of recovery (LOR), and that peak symptom severity would be associated with longer LOR in both males and females. Among females, we hypothesized that non-HC users would have longer LOR and higher peak symptom severity than HC users. Ninety collegiate student-athletes were included in this study (40 males, 50 females; 24 HC users, 25 non-HC users). Demographic, injury, and recovery information was abstracted via retrospective record review. LOR was defined as days between injury and clearance for full return to play by team physician. Peak symptom severity score (Sport Concussion Assessment Tool [SCAT] 2 or 3) was used in analyses. Study results revealed that males had shorter LOR than females (F[1, 86] = 5.021, p < 0.05, d = 0.49), but had comparable symptom severity scores. Symptom severity was strongly related to LOR for males (r = 0.513, p < 0.01) but not females (r = −0.003, p > 0.05). Among females, non-HC users demonstrated higher symptom severity than HC users (F[1,47] = 5.142, p < 0.05, d = 0.70). No significant differences between female HC users and non-HC users on LOR were observed. This study provides evidence for differential concussion outcomes between male and female collegiate athletes and between HC users and nonusers among females.

Keywords: : concussion, HC, mild traumatic brain injury, sex differences

Introduction

A concussion is a brain injury induced by a blow to the head or body that initiates a cascade of pathophysiological processes, resulting in clinical symptoms such as acute altered consciousness, headache, fatigue, slowed processing, and emotional lability.1 Approximately 1,600,000–3,800,000 concussions occur in sports and recreational activities each year in the United States.2 Among varsity collegiate student-athletes, ∼10,500 concussions occur annually, with incidence rates steadily increasing over the past several decades.3–6 Student athletes who sustain a concussion often experience disruptive academic, emotional, cognitive, and physical difficulties. 1,7–9 Although a majority of student athletes recover within 1–2 weeks after injury, many continue to experience symptoms outside of this time frame.1,10 Multiple factors are associated with poorer outcomes (e.g., longer symptom duration) following concussion, including age,11 pre-existing depression,12–14 and loss of consciousness from injury.1 The effect of sex on outcomes following concussion, however, remains controversial. Several major studies have highlighted the need to further understand whether females are at risk for greater impairment following concussion.15,16

Studies examining sex differences in outcomes following concussion yield conflicting evidence. Some studies report that females experience greater symptom burden17–20 and greater cognitive deficits in certain domains17,18,21,22 than males post-concussion. Other studies, however, do not find any significant sex differences in symptoms 21–24 or cognitive performance 25 post-concussion. Ambiguity regarding sex differences in post-concussion symptom levels may stem, in part, from a reporting bias, as females may be more likely than males to be forthcoming when reporting concussion symptoms.4,16

There is limited research regarding sex differences in length of recovery (LOR) following concussion. Three prior studies have examined sex differences in recovery time. Frommer and colleagues did not detect sex differences in symptom resolution time in high school athletes.23 However, the data were collected across 100 high schools with inconsistent operationalization of outcomes across sites. Baker and colleagues found that adolescent females had a significantly greater number of days between injury and symptom resolution than did adolescent males following sports-related concussion.7 Stone and colleagues found that females took ∼6 days longer than males to begin their return-to-play progression in a combined middle school, high school, and collegiate athlete sample.26 To our knowledge, sex differences in LOR following sports-related concussion have not been studied specifically among college athletes. With >460,000 collegiate student-athletes competing at the varsity level alone in the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) and with concussion incidence at this level on the rise, study of this population is critical.27

Another area warranting further study is the hormonal influence on concussion outcomes among females. Preliminary evidence suggests that hormonal contraception (HC) may moderate outcomes in female athletes following concussion. In the single human study to date examining this topic, concussed women taking oral contraceptive pills (OCP) had significantly lower total symptom severity and fewer number of symptoms than concussed women not using OCP.28 In the rodent model, higher estrogen levels exacerbated brain injury effects in female rats.29 OCP regulate, and generally lower, estrogen and other female reproductive hormone levels in the body.30,31 Therefore, the decrease in circulating hormone levels found in HC users may be a protective factor following concussive injuries. To our knowledge, there are no studies to date examining the relationship between hormonal contraception and LOR following concussion in collegiate female athletes.

The purpose of this study was to examine sex and female-specific differences in clinical outcomes following concussion in collegiate varsity athletes. First, we examined sex differences in clinical outcomes following concussion in collegiate varsity athletes, including LOR and peak symptom severity. We hypothesized that females would have longer LOR and that peak symptom severity would be predictive of longer LOR in both males and females, controlling for premorbid and injury characteristics. Second, we examined differences in clinical outcomes following concussion among female athletes using HC (i.e., oral contraceptive pills and NuvaRing) versus females not using HC (non-HC) at the time of injury. We hypothesized that non-HC females would have longer LOR and higher peak symptom severity scores than HC females, controlling for premorbid and injury characteristics.

Methods

Participants and recruitment

All varsity athletes at a single Division I university who sustained one or more concussions during their collegiate athletic careers between January 2011 and December 2016 were recruited for this study via email to provide electronic consent for review of their student treatment record. Diagnosis of concussion was made by a team physician according to the criteria put forth by the International Conference on Concussion in Sport (3rd and 4th).1,32 Of the 238 individuals who sustained a concussion during this period, 121 provided consent, 6 actively declined consent, and 111 did not respond. Records were reviewed for compliance with the following inclusion criteria: no history of a neurological disorder (e.g., epilepsy) other than migraines; no psychiatric disorder other than anxiety and depression; specific dates of injury and clearance to return to full contact participation; recovery period uninterrupted by an extended school holiday break such as spring break, winter holidays, or summer; and having been assessed in the clinic within 3 days of injury (although within 24 h is standard practice and was true for the majority of cases). Of the 121 cases, 92 met inclusion criteria. Two additional cases were excluded because recovery from concussion was complicated by a simultaneous illness (i.e., viral illness and a sinus infection); clinician notes indicated ambiguity regarding whether persisting symptoms (e.g., headaches, fatigue, nausea) were caused by post-concussive effects or the unrelated illness. Approval for this study was granted from the Northwestern University's Institutional Review Board.

Procedure

Athletes' electronic treatment records were retrospectively reviewed. Demographic and medical history information, including history of concussion prior to college, was abstracted from the health documentation completed by medical staff upon a student's entrance to the university. Records were reviewed for concussions sustained during the athlete's collegiate athletic career. If an athlete sustained multiple concussions during his or her collegiate career, data from the first injury only were included in this study. In eight cases, the athlete's first injury did not meet study criteria (e.g., recovery was interrupted by a school break or there was missing recovery information), so data from the athlete's second concussion were used for this study.

Determining sex and HC-group classification

Sex was determined based on sex assigned at birth recorded in health documents completed upon entrance to the university. Females were divided into hormonal contraception users (HC) and non-hormonal contraception users (non-HC) based on (1) the medications recorded at the time of injury, which was individually confirmed and recorded by the treating clinician in the injury notes, and (2) review of the female health questionnaire completed prior to each academic year. Women taking OCP (n = 23) or using the NuvaRing (n = 1), which releases similar hormone levels as OCP into the bloodstream, were assigned to the HC group. Women not using oral contraceptive pills, NuvaRing, or any other hormonal contraception method (n = 25) were assigned to the non-HC group. The single female in this study using an intrauterine device (IUD) (Mirena®) was excluded from HC vs. non-HC analyses because of the unique nature of the Mirena IUD. The Mirena IUD releases hormones that primarily remain concentrated in the uterus. However, a minimal amount of hormones, relative to OCP-users, circulates through the bloodstream.33 Because of the variation in plasma hormone levels in Mirena IUD users compared with OCP/NuvaRing users, the Mirena IUD user was excluded from the HC vs. non-HC analyses, but was included in the male vs. female analyses.

Concussion outcomes

Primary concussion outcome variables were abstracted from the athlete's clinic notes, which are composed of assessments completed by team physicians and athletic trainers. Per the university's athletics' recommended protocol, athletes completed the Sport Concussion Assessment Tool, 2nd ed. (SCAT-232) or 3rd ed. (SCAT-31) with an athletic trainer immediately after the concussion was suspected or reported. The SCAT-2 and −3 contain an identical symptom rating scale, composed of 22 total symptoms rated on a seven point Likert scale of severity from 0 (none) to 6 (severe). Therefore, the symptom evaluation yields two scores: (1) total symptom number (range: 0–22), and 2) symptom severity score (range: 0–132). In accordance with university recommendations, athletes diagnosed with concussion completed a symptom inventory at least every 24 h following the suspicion or reporting of a concussion until clearance for full return to play. The athlete's peak symptom severity score was used in analyses as the indicator of peak symptom burden. For all athletes in this study, the peak symptom burden ratings occurred within 5 days of injury.

The university's athletic protocol requires concussed athletes to refrain from all physical activity, including athletic participation, until symptoms have returned to baseline levels for at least 24 h. At this time, athletes begin the return-to-play protocol, which, at the time of study, consisted of gradual, stepwise increase in physical exertion, starting with light aerobic activity (e.g., stationary biking) and progressing to noncontact athletic participation. After progressing to noncontact participation, athletes complete computerized cognitive testing (Immediate Post-Concussion Assessment and Cognitive Test [ImPACT®]) and are evaluated by an external independent neurology consultant. The team physician then makes final clearance for full-contact athletic participation. The return to play protocol takes a minimum of 5 days. LOR was calculated by subtracting the number of days between final clearance by the team physician and the date of injury. The physician clearance date was used instead of the symptom resolution date, because some athletes experience a return of symptoms once they begin the gradual return to play protocol, indicating that the injury has likely not resolved.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive analyses were conducted to evaluate group differences in demographic and injury characteristics (males vs. females and HC vs. non-HC females); one way analyses of variance (ANOVA) was used for continuous data and χ2 tests were used for categorical data (α = 0.05). Because of non-normal distributions, LOR and peak symptom severity were log-transformed for main hypotheses testing.

To evaluate sex differences in symptom burden and LOR, we conducted a regression analysis predicting LOR by sex and the sex-by-symptom severity interaction. To evaluate the effect of hormonal contraception on symptom severity and LOR outcomes in female athletes, we conducted two separate ANOVA tests evaluating group differences on LOR and symptom severity. Post-hoc testing was conducted based on main omnibus test results. Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen's d formula34 on non-log transformed values.

Results

Demographic and injury characteristics

See Table 1 for group demographic information. The racial composition of the current sample was similar to that of all Division I, II, and III athletes combined for the 2012–2013 academic year.35 In the total sample, ∼50% of concussions occurred during practice, 40% occurred during competition, and 10% were non-athletic but occurred during the competitive season. The majority of injuries analyzed took place during freshman (26%) or sophomore (38%) years of college, which is not unexpected given that an athlete's first concussion was typically used in analyses if multiple concussions occurred over the course of that person's collegiate athletic careers. A diverse number of athletic teams were represented in this sample, but the majority of individuals were members of the football (26%), soccer (20%), basketball (14%), or swim and dive (10%) teams. Although athletic protocol mandates that athletes report concussion symptoms immediately and abstain from play until further evaluation, ∼46% of men and 44% of women reported returning to play during the same game or practice after an initial blow to the head that was later determined to be the causal impact of concussion symptoms (Table 2). Reasons for athletes returning to play, abstracted from clinic notes, included symptoms not commencing until several hours after the hit or the athlete failing to recognize symptoms as being reflective of a concussive injury. Although not reported in clinic notes, it is also possible that athletes returned to play in the same game or practice because of a desire to remain in competition or a desire not to let teammates down.36

Table 1.

Sample Demographic Information

| Males (n = 40) | Females (n = 50) | p | Non-hormonal contraceptive users (n = 24) | Hormonal contraceptive users (n = 25) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (M[SD]) | 19.8 (1.2) | 19.6 (1.1) | ns | 19.2 (1.0) | 20.1 (1.1) | 0.001 |

| Race | ||||||

| % Caucasian | 26 (65%) | 41 (82%) | ns | 18 (75%) | 22 (88%) | ns |

| % African American | 13 (33%) | 5 (10%) | ns | 3 (13%) | 2 (8%) | ns |

| Hx of ≥1 concussion | 22 (55%) | 12 (24%) | 0.003 | 4 (17%) | 7 (28%) | ns |

| Hx of depression | 0 (0%) | 4 (8%) | ns | 0 (0%) | 4 (16%) | ns |

| Hx of anxiety | 2 (5%) | 1 (2%) | ns | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | ns |

| Hx of ADHD | 1 (2%) | 2 (4%) | ns | 1 (4%) | 1 (4%) | ns |

| Hx of headaches | 3 (7%) | 6 (15%) | ns | 4 (17%) | 2 (8%) | ns |

All data are represented by group count (percentage of group) unless otherwise noted. One female with an intrauterine device was excluded from the hormonal contraceptive (HC) vs. non-HC group analyses.

M(SD), mean (standard deviation); ns, group comparisons are not significant at the p < 0.05 level; hx, history; ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Table 2.

Injury and Outcome Information

| Males (n = 40) | Females (n = 50) | p | Non-hormonal contraceptive users (n = 24) | Hormonal contraceptive users (n = 25) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amnesia | 8 (20%) | 2 (4%) | 0.016 | 0 (0%) | 2 (8%) | ns |

| Loss of consciousness | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | ns | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | ns |

| RTP in same day | 18 (47%) | 22 (44%) | ns | 11 (46%) | 10 (40%) | ns |

| LOR (M[SD]) | 13(9) | 22 (23) | 0.031 | 24(30) | 20(19) | ns |

| Peak Symptom Severity (M[SD]) | 26(21) | 22(14) | ns | 27(16) | 18(10) | 0.017 |

All data are represented by group count (percentage of group) unless otherwise noted. One female with an intrauterine device was excluded from the hormonal contraceptive (HC) vs. non-HC group analyses.

M(SD), mean (standard deviation); p, statistical significance value for group comparisons (either Pearson's χ2 or analyses of variance tests); ns, group comparisons are not significant at the p < 0.05 level; RTP, return to play; LOR, length of recovery; Peak Symptom Severity, the individual's highest symptom severity score from the Sport Concussion Assessment Tool (SCAT)-2 or SCAT-3 during recovery. Note that log-transformed scores were used in the main analyses.

Male and female athletes significantly differed in their history of concussion: 56% of males had experienced one or more prior documented concussions (15 with a single prior injury, 7 with two to three prior injuries) compared with 24% of females (eight with a single prior injury, four with two to three prior injuries) (Table 1). Males were also significantly more likely than females to experience either retrograde or anterograde amnesia associated with the concussive injury (Table 2). To determine whether history of previous concussion and/or amnesia should be added as covariates in the main hypotheses tests, analyses of covariance tests were conducted. Results indicated no significant relationship (p > 0.05) between either of these variables (history of previous concussion and amnesia associated with the injury) and outcome variables of interest: LOR and symptom severity. Therefore, these variables were not added to the main statistical models. HC and non-HC females significantly differed by age; however, the mean difference was only 1 year, and not of clinical significance given the outcome variables.

Sex differences in symptom severity and LOR

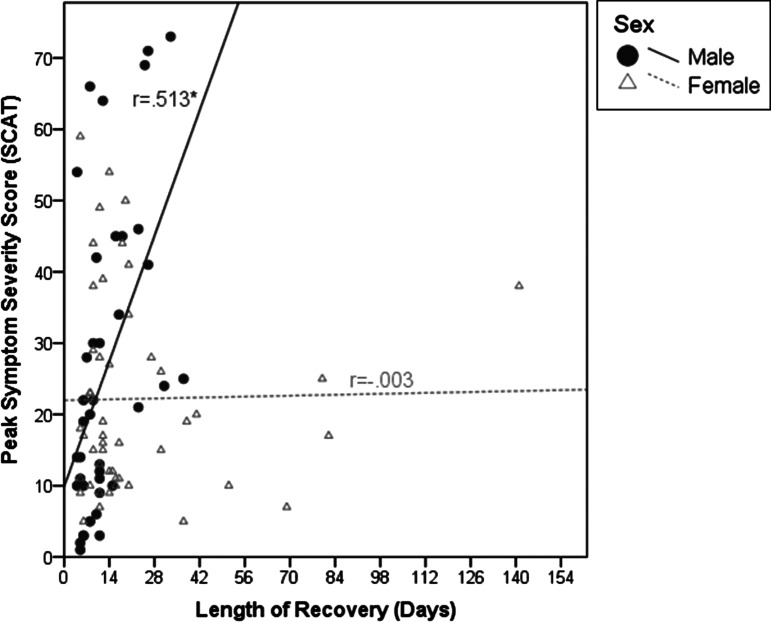

Males and females did not significantly differ on symptom severity (Table 2). Regression analysis indicated a main effect of sex (F[1, 86] = 5.021, p < 0.05, d = 0.49) on LOR, such that males on average were cleared for full return to play within 13 days and females within 22 days (Table 2). There was also a significant interaction between sex and symptom burden (F[2, 86] = 4.357, p < 0.05) such that symptom severity was strongly related to LOR for males (r = 0.513, p < 0.01) but not females (r = −0.003, p > 0.05); correlations were conducted on log-transformed LOR and symptom severity. Correlations on raw data (non-log transformed) are presented in Figure 1.

FIG. 1.

Sex differences in the relationship between symptom severity and length of recovery. R values indicate Pearson's correlation coefficient values for each sex using non-log transformed data. * indicates significance at the p < 0.01 level. Peak Symptom Severity score is the athletes' highest Symptom Severity (range 0–132) recorded on the Sports Concussion Assessment Tool, 2nd ed.32 or 3rd ed.1 during recovery. Note that for main omnibus tests, Peak Symptom Severity and Length of Recovery values were log transformed.

HC effects on symptom severity and length of recovery

Non-HC females demonstrated significantly higher symptom severity scores compared to HC-females (F[1,47] = 5.142, p < 0.05, d = 0.70). There were no significant differences between HC and non-HC females on LOR.

Discussion

This study sought to examine the effects of sex and hormonal contraception on outcomes following concussion. We found that female collegiate athletes' experienced, on average, longer LOR following concussion than male athletes. Further, symptom severity was strongly related to LOR in males but not in females. Among females, athletes using HC (e.g., OCP or NuvaRing) tended to report lower symptom severity during recovery from concussion than females not using HC. No differences in LOR were observed in female athletes using HC versus those not using HC.

To our knowledge, the current study is the first to examine sex differences in length of recovery among collegiate athletes. Prior studies of adolescent athletes have yielded inconsistent results regarding sex differences in recovery time.7,23,26 In this study, males showed comparable severity scores and shorter recovery time than females. Further, male athletes' self-reported symptom severity was highly correlated with LOR. The consensus statement from the 5th International Conference on Concussion in Sport states that “the strongest and most consistent predictor of slower recovery from [sports- related concussion] is the severity of a person's symptoms in the... initial few days, after injury.”37 Our data suggest, however, that self-reported symptom severity data may have predictive validity regarding LOR for male, but not female, athletes.

Several explanations may account for the longer LOR in female versus male athletes. Female athletes generally have decreased neck strength compared with male athletes, and females tend to have greater head-neck acceleration and displacement upon impact than males.38–40 Greater head-neck acceleration and head displacement have been associated with longer recovery time and cognitive deficits following brain injury.41 It is also possible female athletes approach return-to-play following concussion with more caution than males. Prior work suggests that females with head trauma may have greater self-awareness of their cognitive deficits than males;42 if this holds true in mild brain injuries, perhaps greater insight yields greater caution among women. Female collegiate athletes may also approach return-to-play more prudently than males because of females' greater emphasis on academic success in college43,44 and could have lower aspirations for professional athletic participation than males because of decreased professional opportunities and compensation. In addition, female athletes may be handled more cautiously by clinicians following concussion than males, which could lengthen time to clearance for full return to play.45,46 Finally, baseline differences in hormones such as progesterone and estrogen may be implicated in the differential sex outcomes between male and female concussed athletes, but this has not yet been elucidated in the literature.17

The current study replicates the findings of Mihalik and colleagues with regard to the effect of hormonal contraception on symptom outcomes.28 Specifically, both the Mihalik and the current studies found that women not using HC reported significantly higher peak symptom severity scores. There are several explanations for lower symptom severity ratings in women using HC. Some studies have found that higher levels of hormones, such as estrogen and progesterone, are associated with increased pain perception.47,48 Therefore, it may be that HC users and non-users have similar neurometabolic responses to concussion, but that the subjective appraisal of symptom severity is lower in females using HC. An alternate explanation is that decreased and regulated estrogen and progesterone levels provide a neuroprotective effect for HC users following head trauma.29,49 Emerson and colleagues demonstrated that female rats with acutely elevated estrogen experienced worse neurometabolic disruption and adverse functional outcomes than female rats without elevated estrogen.29 This finding suggests that decreased estrogen, observed in females using hormonal contraception, may be advantageous in concussion recovery. This finding stands in contrast to a larger body of literature demonstrating the neuroprotective effects of increased estrogen and progesterone in moderate to severe traumatic brain injury (TBI).50 It may be that women using HC are protected from a sudden drop in progesterone and estrogen that is experienced by non-HC users following concussion.49 Specifically, Wunderle and colleagues proposes that women with unregulated progesterone levels injured during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, when progesterone levels are highest, experience a sudden drop in progesterone, which adversely affects outcomes. Therefore, women using HC that regulates progesterone are not prone to the adverse consequences associated with the abrupt progesterone drop.

Several limitations to the current study warrant mention. First, a selection bias may exist in which men and women who experienced more profound and lasting effects from concussion were more motivated or inspired to respond to the recruitment email to provide consent. Therefore, LOR and symptom outcomes may not be representative of all intercollegiate athletes. Similarly, athletes in this sample are from a Division I university; pressure to return to play may be greater at this competitive level compared with others, which could limit the generalizability of the LOR data. Second, symptom outcomes were not evaluated by domain, and there may be more sex-specific patterns of symptoms by domain (e.g. somatic, emotional). Finally, results should be interpreted with caution given the retrospective nature of the study. Future studies are needed to thoroughly investigate the effects of sex, hormonal contraception, and menstrual cycle on specific domains of symptoms and cognitive performance following concussion.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.McCrory P., Meeuwisse W.H., Aubry M., Cantu B., Dvořák J., Echemendia R.J., Engebretsen L., Johnston K., Kutcher J.S., Raftery M., Sills A., Benson B.W., Davis G.A., Ellenbogen R.G., Guskiewicz K., Herring S.A., Iverson G.L., Jordan B.D., Kissick J., McCrea M., McIntosh A.S., Maddocks D., Makdissi M., Purcell L., Putukian M., Schneider K., Tator C.H., and Turner M. (2013). Consensus statement on concussion in sport: the 4th International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Zurich, November 2012. Br. J. Sports Med. 47, 250–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langlois J.A., Rutland-Brown W., and Wald M.M. (2006). The epidemiology and impact of traumatic brain injury: a brief overview. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 21, 375–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Covassin T., Swanik C.B., and Sachs M.L. (2003). Epidemiological considerations of concussions among intercollegiate athletes. Appl. Neuropsychol. 10, 12–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daneshvar D.H., Nowinski C.J., McKee A.C., and Cantu R.C. (2011). The epidemiology of sport-related concussion. Clin. Sports Med. 30, 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kilcoyne K.G., Dickens J.F., Svoboda S.J., Owens B.D., Cameron K.L., Sullivan R.T., and Rue J.-P. (2014). Reported concussion rates for three Division I football programs an evaluation of the new NCAA concussion policy. Sports Health 6, 402–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zuckerman S.L., Kerr Z.Y., Yengo-Kahn A., Wasserman E., Covassin T., and Solomon G.S. (2015). Epidemiology of sports-related concussion in NCAA athletes from 2009–2010 to 2013–2014: incidence, recurrence, and mechanisms. Am. J. Sports Med. 43, 2654–2662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker J.G., Leddy J.J., Darling S.R., Shucard J., Makdissi M., and Willer B.S. (2016). Gender differences in recovery from sports-related concussion in adolescents. Clin. Pediatr. (Phila.) 55, 771–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins M.W., Grindel S.H., Lovell M.R., Dede D.E., Moser D.J., Phalin B.R., Nogle S., Wasik M., Cordry D., Daugherty M.R., and Sears S.F. (1999). Relationship between concussion and neuropsychological performance in college football players. JAMA 282, 964–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sady M., Vaughan C., and Gioia G. (2011). School and the concussed youth: recommendations for concussion education and management. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 22, 701–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McClincy M.P., Lovell M.R., Pardini J., Collins M.W., and Spore M.K. (2006). Recovery from sports concussion in high school and collegiate athletes. Brain Inj. 20, 33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams R.M., Puetz T.W., Giza C.C., and Broglio S.P. (2015). Concussion recovery time among high school and collegiate athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 45, 893–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chamelian L., and Feinstein A. (2006). The effect of major depression on subjective and objective cognitive deficits in mild to moderate traumatic brain injury. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 18, 33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iverson G.L. (2006). Misdiagnosis of the persistent postconcussion syndrome in patients with depression. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 21, 303–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mooney G., Speed J., and Sheppard S. (2005). Factors related to recovery after mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 19, 975–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCrea M., Guskiewicz K., Randolph C., Barr W.B., Hammeke T.A., Marshall S.W., Powell M.R., Woo Ahn K., Wang Y., and Kelly J.P. (2013). Incidence, clinical course, and predictors of prolonged recovery time following sport-related concussion in high school and college athletes. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 19, 22–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Makdissi M., Davis G., Jordan B., Patricios J., Purcell L., and Putukian M. (2013). Revisiting the modifiers: how should the evaluation and management of acute concussions differ in specific groups? Br. J. Sports Med. 47, 314–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Broshek D.K., Kaushik T., Freeman J.R., Erlanger D., Webbe F., and Barth J.T. (2005). Sex differences in outcome following sports-related concussion. J. Neurosurg. 102, 856–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colvin A.C., Mullen J., Lovell M.R., West R.V., Collins M.W., and Groh M. (2009). The role of concussion history and gender in recovery from soccer-related concussion. Am. J. Sports Med. 37, 1699–1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henry L.C., Elbin R.J., Collins M.W., Marchetti G., and Kontos A.P. (2016). Examining recovery trajectories after sport-related concussion with a multimodal clinical assessment approach. Neurosurgery 78, 232–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Preiss-Farzanegan S.J., Chapman B., Wong T.M., Wu J., and Bazarian J.J. (2009). The relationship between gender and postconcussion symptoms after sport-related mild traumatic brain injury. PM R 1, 245–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Covassin T., Schatz P., and Swanik C.B. (2007). Sex differences in neuropsychological function and post-concussion symptoms of concussed collegiate athletes. Neurosurgery 61, 345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kontos A.P., Covassin T., Elbin R.J., and Parker T. (2012). Depression and neurocognitive performance after concussion among male and female high school and collegiate athletes. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 93, 1751–1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frommer L.J., Gurka K.K., Cross K.M., Ingersoll C.D., Comstock R.D., and Saliba S.A. (2011). Sex differences in concussion symptoms of high school athletes. J. Athl. Train. 46, 76–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCrea M., Guskiewicz K., Randolph C., Barr W.B., Hammeke T.A., Marshall S.W., Powell M.R., Woo Ahn K., Wang Y., and Kelly J.P. (2013). Incidence, clinical course, and predictors of prolonged recovery time following sport-related concussion in high school and college athletes. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 19, 22–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henry L.C., Elbin R.J., Collins M.W., Marchetti G., and Kontos A.P. (2016). Examining recovery trajectories after sport-related concussion with a multimodal clinical assessment approach. Neurosurgery 78, 232–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stone S., Lee B., Garrison J.C., Blueitt D., and Creed K. (2017). Sex differences in time to return-to-play progression after sport-related concussion. Sports Health 9, 41–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National College Athletic Association. (2017). Sport sponsorhip participation and demographics search [student-athlete data: 2016–2017 overall figures]. http://web1.ncaa.org/rgdSearch/exec/main (last accessed March 2, 2018).

- 28.Mihalik J.P., Ondrak K.S., Guskiewicz K.M., and McMurray R.G. (2009). The effects of menstrual cycle phase on clinical measures of concussion in healthy college-aged females. J. Sci. Med. Sport 12, 383–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emerson C.S., Headrick J.P., and Vink R. (1993). Estrogen improves biochemical and neurologic outcome following traumatic brain injury in male rats, but not in females. Brain Res. 608, 95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gaspard U.J., Romus M.A., Gillain D., Duvivier J., Demey-Ponsart E., and Franchimont P. (1983). Plasma hormone levels in women receiving new oral contraceptives containing ethinyl estradiol plus levonorgestrel or desogestrel. Contraception 27, 577–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mishell D.R., Thorneycroft I.H., Nakamura R.M., Nagata Y., and Stone S.C. (1972). Serum estradiol in women ingesting combination oral contraceptive steroids. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 114, 923–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCrory P., Meeuwisse W., Johnston K., Dvorak J., Aubry M., Molloy M., and Cantu R. (2009). Consensus statement on concussion in sport: The 3rd International Conference on Concussion in Sport Held in Zurich, November 2008. J. Athl. Train. 44, 434–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nilsson C.G., Lähteenmäki P., and Luukkainen T. (1980). Levonorgestrel plasma concentrations and hormone profiles after insertion and after one year of treatment with a levonorgestrel-IUD. Contraception 21, 225–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohen J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. Lawrence Earlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Collegiate Athletic Association (2017). Sport Sponsorship, Participation and Demographics Search [2012–2013] overall figures. http://web1/ncaa.org/rgdSearch/exec/main (last accessed March 2, 2018).

- 36.McCrea M., Hammeke T., Olsen G., Leo P., and Guskiewicz K. (2004). Unreported concussion in high school football players: implications for prevention. Clin. J. Sport Med. 14, 13–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCrory P., Meeuwisse W.H., Dvořák J., Echemendia R.J., Engebretsen L., Feddermann-Demont N., McCrea M., Makdissi M., Patricios J., Schneider K.J., and Sills A.K. (2017). 5th International Conference on Concussion in Sport (Berlin). Br. J. Sports Med. 51, 837–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barnes B.C., Cooper L., Kirkendall D.T., McDermott T.P., Jordan B.D., and Garrett W.E. (1998). Concussion history in elite male and female soccer players. Am. J. Sports Med. 26, 433–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Collins C.L., Fletcher E.N., Fields S.K., Kluchurosky L., Rohrkemper M.K., Comstock R.D., and Cantu R.C. (2014). Neck strength: a protective factor reducing risk for concussion in high school sports. J. Prim. Prev. 35, 309–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tierney R.T., Sitler M.R., Swanik C.B., Swanik K.A., Higgins M., and Torg J. (2005). Gender differences in head-neck segment dynamic stabilization during head acceleration. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 37, 272–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gennarelli T.A., Seggawa H., Wald U., Czernicki Z., Marsh K., and Thompson C. (1982). Physiological response to angular acceleration of the head, in: Head Injury: Basic and Clinical Aspects. Grossman, Roberg, and Gildenberg P.L., (eds). Raven Press: New York, pps. 129–140. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Niemeier J.P., Perrin P.B., Holcomb M.G., Rolston C.D., Artman L.K., Lu J., and Nersessova K.S. (2014). Gender differences in awareness and outcomes during acute traumatic brain injury recovery. J. Womens Health 23, 573–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheard M. (2009). Hardiness commitment, gender, and age differentiate university academic performance. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 79, 189–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith F. (2007). “It's not all about grades”: accounting for gendered degree results in geography at Brunel University. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 28, 167–178. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Safran D.G., Rogers W.H., Tarlov A.R., McHorney C.A., and Ware J.E. (1997). Gender differences in medical treatment: the case of physician-prescribed activity restrictions. Soc. Sci. Med. 45, 711–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yard E.E., and Comstock R.D. (2009). Compliance with return to play guidelines following concussion in US high school athletes, 2005–2008. Brain Inj. 23, 888–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Choi J.C., Park S.K., Kim Y.-H., Shin Y.-W., Kwon J.S., Kim J.S., Kim J.-W., Kim S.Y., Lee S.G., and Lee M.S. (2006). Different brain activation patterns to pain and pain-related unpleasantness during the menstrual cycle. Anesthesiol. J. Am. Soc. Anesthesiol. 105, 120–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fillingim R.B., Maixner W., Girdler S.S., Light K.C., Harris M.B., Sheps D.S., and Mason G.A. (1997). Ischemic but not thermal pain sensitivity varies across the menstrual cycle. Psychosom. Med. 59, 512–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wunderle K., Hoeger K.M., Wasserman E., and Bazarian J.J. (2014). Menstrual phase as predictor of outcome after mild traumatic brain injury in women. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 29, E1–E8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brotfain E.E., Gruenbaum S., Boyko M., Kutz R., Zlotnik A., and Klein M. (2016). Neuroprotection by estrogen and progesterone in traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 14, 641–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]