Abstract

Introduction

Burn injuries are among the most prevalent health conditions worldwide that happen mainly in children, military, and victims of fire accidents. The previous literature had general limitations in that it focused on the retrospective study design, which can be prone to incomplete data or lack the full evidence of the problem, however, this study is a prospective study that gives a clue to the possible determinant factors of burn injury in pediatrics.

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to assess the clinical pattern and outcome of burn injury in children at the AaBet trauma center in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, between July 2016 and July 2020.

Methods

An institutional-based prospective study was conducted in an AaBet trauma center. The study participants were chosen using a systematic random sampling method and followed for 4 years to determine their clinical outcomes after burn injury. A pretested observational check list was used to collect the data. The collected data were coded, entered Epi-data version 4.6, and exported to SPSS version 26 for descriptive and inferential analysis. A binary logistic regression model was used to identify factors associated with burn injury on the adjusted odd ratio with a 95% confidence interval at a p-value of < .05.

Results

A total of 256 patients were recruited for this study. Scald burns accounted for 50.8% of the injury mechanisms, with 93.8% of the incidents occurring in private residences. Second-degree burns were the most common presentation of the victims (83%). Lower limbs were the most frequently burned body part (47%). Over 70% of the victims had 20% of their body surface area burned. Intentional burns accounted for 1.2% of all burn victims. The length of the hospital stay ranged from 1 day to 164 days with a mean stay of 24.73 days. Eight patients (3.1%) died during the study period.

Conclusion and recommendation

Pediatric burn incidences showed no significant discrepancies between males and females. Scald and open flame are the common causes of burn injury. Most incidents occurred in indoor settings, and most of the victims had not received first aid at home. Most patients left the hospital with no or minimal complications. Only 3.1% of the patients died. Patients who had burn-associated injuries were 98.8% less likely to be alive than those who had no associated injuries at all. For all governmental and non-governmental bodies, it is highly recommended to give priority to preventive measures and education on the need for appropriate prehospital care.

Keywords: burn, pediatrics, pattern, the clinical outcome

Introduction

A burn is defined as an injury to the skin or other tissue caused by thermal trauma. It occurs when some or all of the cells in the skin or other tissues are destroyed by hot liquids (scalds), hot solids (contact burns), flames (flame burns), radiation, radioactivity, electricity, friction, or contact with chemicals (Peck, 2011). Burn injuries are among the most prevalent health conditions worldwide that happen mainly in children, military, and victims of fire accidents. It is one of the significant causes of momentary as well as lasting disabilities in patients (Long et al., 2022). Based on the depth of the burn injury, it is also categorized as first degree, which involves only the epidermis, for example, sunburn. Second-degree burn involves the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue. It is usually highly painful. Third-degree burns, which involve muscle and bone, are usually painless (Patterson et al., 2023).

Globally, 3.9 pediatric deaths per 100,000 people were recorded, putting infants at the greatest risk of death from burn injury (Farzan et al., 2023). The World Health Organization estimates that over 310,000 people die each year because of burns in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), accounting for approximately 95% of all annual burn deaths (Toolaroud et al., 2023). Of all unintentional injury deaths, 10% are due to fire-related burns. The death rate from burns was 11 times higher in LMICs than in high-income countries (McLoughlin & McGuire, 1990).

Around 90% of burn cases happens in Africa and South-East Asia (Lagziel et al., 2023). According to these statistics, 80% of burn injuries occurs in children under the age of ten. Pediatric burns are fatal, even with a small total body surface area (TBSA) burn. In LMICs, even 20% of the TBSA can be fatal (Tiruneh et al., 2022). In high-income countries, a pediatric patient with a 60% TBSA burn survives (Al-Naimat & Abdel Razeq, 2023).

A Review of Literature

The previous studies (literatures) in Ethiopia agree with global figures, revealing that children under the age of ten account for nearly half of all burn victims (Adane et al., 2023). However, there are still significant gaps in understanding the factors that contribute to burn incidents as well as gaps in showing the actual figures of morbidity and mortality burden in Ethiopia (Tiruneh et al., 2022). A community-based study in northern Ethiopia's Mekelle Town showed the highest incidence of burns among children. Similarly, a retrospective study performed at Ayder Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Mekelle, Ethiopia, shows that the most commonly affected age group was children under 10 years of age. Both studies found that scald burns and domestic settings are the most common causes and settings for burns in the pediatric population (Biru & Mekonnen, 2020).

Statement of the Problem

The inadequacy of information on the incidence is holding back the responsible bodies in legislation and policy formulation toward preventive measures, in-hospital care, and post-discharge care (Banga et al., 2023). The previous literature (studies) had a general limitation in that the study design was retrospective and only focused on prevalence, so important data was missing or incomplete; thus, it could not provide in-depth details on the problems. In addition, a previous study (literature) did not provide enough information about the overall patterns of burn injury (Killey et al., 2023). This study could be a prospective approach focused on the cause, clinical pattern, and outcomes of burn injury in children. In addition, this study provides basic information on the risk, prevalence, and determinants of burn injury in children that is valuable for the academic community, service providers, and health care professionals. The purpose of this study was to assess the causes, mechanisms, clinical manifestations, types, and outcomes of burn injury in children.

Aims

This study aimed to assess the clinical pattern and the outcome of burn injuries among children at the AaBet trauma center in Addis Ababa between July 2016 and July 2020.

Methods

Period, Design, and Area

From July 2016 to July 2020, an institutional-based prospective (follow-up) study was conducted at the AaBet burn center in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. AaBet Hospital was opened with the mission of providing burn, emergency, and trauma care. It is the only major trauma center in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The hospital serves over 7,000 patients annually, with 250 beds. It started working on July 2016 to provide tertiary level referral and treatment. This burn unit has 29 beds, of which 12 are reserved for pediatric burn victims, 31 trained nurses, 7 plastic surgeons, 6 general practitioners, and rotating residents with an operation room (Adal & Emishaw, 2023; Adal, Abebe et al., 2023; Adal, Hiamanot et al., 2023).

Research Questions

What is the clinical pattern of burn injuries in children?

What are the possible long-term clinical outcomes for these burn-injured children?

What are the associated factors in the clinical outcomes for children with burn injuries?

Sample

The actual sample size for the study was determined using a single population proportion formula:{n = [(zα/2)2p (1 − p)]/d2}, n = sample size, zα/2 = 95% confidence level, d = margin of error, and P = the proportion (38.5%) (11). Since the number of burn injury patients was less than 10,000, a correction formula was applied: nf = {(n*N)/N + n}, nf = final sample size, n = sample size, N = total study population. The final corrected sample size was 273. Systematic random sampling was used to select the respected patient for a 4-month duration and follow them for 4 years to determine the final clinical outcome of the injury (died or alive).

Inclusion Criteria

All patients with a burn injury who were 14 years old or younger were included.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients or their family not willingness to participate in the study were excluded.

Data Collection Tools

Data collection was performed using a pretested observational checklist format developed from reviewing different kinds of literature (Biru & Mekonnen, 2020). The checklist contains sociodemographic and clinical presentation, management profiles, and treatment outcome questions for burn injury in children.

Clinical pattern of burn injury: Characteristics of burns during the acute presentation. These include age distribution, the mechanism of injury, types, clinical features, severity, and the length of the hospital stay (Enkhtuvshin et al., 2023).

Outcome of burn injury: The outcome of burn injury refers to improved/live or died/death. Improved might be without complication or with complication such as scare, disability, or disfiguring (Tiruneh et al., 2022).

Data Quality Control

Before the actual data collection date, data collectors (two BSC nurses) and a supervisor (one MSc, nurse) were trained for two days concerning the overall issue of data collection format. A pretest was performed on 5% of the total sample to ensure the agreement of the data abstraction format with the aim of the study. For 4 years, the outcomes of injured children were monitored with monthly visits to an AaBet burn center hospital. Any errors found in the data abstraction format (checklist) were corrected and modified. Every month during the follow-up, close supervision was carried out with the supervisor and principal investigator. In this study, data were collected using checklists.

Institutional Review Board Approval and Informed Consent

The ethical review board of the College of Health Sciences at Addis Ababa University approved this study (No. 2139 edu.net for ethical approval). It is certified that the study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Statistical Analysis

The data were cleaned, verified for completeness, coded, and entered EPI-Data version 4.6.0.4, and then exported to SPSS version 26 for further analysis. The results are presented in narrations, graphs, and tabulations. The outcome of this study was generally dichotomy (two outcomes), therefore, a binary logistic regression analysis model was used to identify factors that determine child burn injury. The model fitness of the variable was tested using Hosmer and Lemon's method, which yielded a p-value of 0.76. All independent variables with a p-value of < .25 from a bivariate logistic regression analysis were fitted into a multivariate logistic regression analysis to control for the possible effect of confounders. Finally, using an adjusted odd ratio with a 95% confidence interval (CI) and a p-value of < .05, the variables that were independently associated with outcomes of child in burn injury were identified.

Results

In the 4 years of the prospective study from July 2016 to July 2020, 273 sample-size burn victims under the age of 14 were admitted and treated in an AaBet burn center hospital, but 17 injured children were lost to follow-up, so data collection and analysis were performed on 256 patients.

Sample/Sociodemographic Characteristics

Both male and female burn victims were distributed almost equally in the current study. From the total number of burn victims, male patients accounted for 130 (50.8%). The average age of all burn patients was 4.5 years ± 3.94 standard deviation, with patients ranging in age from 6 months to 14 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Distribution of Pediatric Burn Patients at AaBet Hospital From July 2016 to January 2020 (n = 256).

| Characteristics | Frequency (n) | Percentages (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 130 | 50.8% |

| Female | 126 | 49.2% | |

| Age (months) | 0–24 | 97 | 37.9% |

| 25–72 | 97 | 37.9% | |

| 73–168 | 61 | 23.8% | |

| Regions | Addis Ababa | 133 | 52.0% |

| Afar | 1 | 0.4% | |

| Amhara | 9 | 3.5% | |

| Dire Dawa | 1 | 0.4% | |

| Gambelia | 3 | 1.2% | |

| Harari | 1 | 0.4% | |

| Oromia | 98 | 38.3% | |

| Southern Ethiopia | 6 | 2.3% | |

| Somalia | 2 | 0.8% | |

| Tigray | 2 | 0.8% |

Research Question Results

Clinical Pattern of Burn Patients

Scald was the most common cause, affecting 130 (50.8%) of all burn injuries, followed by open flame at 104 (40.6%) and electrical burn at 12 (4.7%), while thermal contact and chemical burn accounted for 7 (2.7%) and 3 (1.2%), respectively. On the other hand, contact burns are seen mostly in early childhood (4.1%), whereas flame and electrical burns are mostly seen among children in their late childhood. Most patients, 239 (93.4%), sought medical attention in the first 24 h of the burn incident. While 11 (4.3%) children presented for medical care between 24 and 48 h. The rest (2.3%) presented after 72 h of the incident. Only 6 (2.3%) reported receiving prehospital care, two reported using cold water, and the rest applied Vaseline, dough, and ground coffee to the burned body site. The majority of burn incidents occurred in domestic settings: 240 (93.8%) occurred at home, 15 (4.9%) occurred in the street, and one flame burn occurred at school. The majority of electrical burns (53.3%) happened outside on the street. The most frequently involved body part was the lower extremity in 136 (53.1%) patients. The upper extremity was involved in 130 (50.8%) patients; and the trunk covered 112 (43.8%) patients. The face/neck and buttocks/genitalia were involved in 72 (28.1%) and 43 (16.8%) patients, respectively. Second-degree burns contributed to the majority of burns 214 (83.6%). The percentage of TBSA burned ranged from 1% to 92%, with a median of 14% (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical Pattern of Burn Injury at AaBet Hospital During Data Collection Period (4 Months), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. n = 256.

| Patient characteristics | Causes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flame frequency (%) | Scald frequency (%) | Electrical frequency (%) | Chemical frequency (%) | Contact frequency (%) | ||

| Age (in months) | 0–24 | 35(36.1) | 59(60.8) | 2(2.1) | 0(0.0) | 1(1.0) |

| 25–72 | 39(39.8) | 53(54.1) | 1(1.0) | 1(1.0) | 4(4.2) | |

| 73–168 | 30(49.2) | 18(29.5) | 9(14.8) | 2(3.3) | 2(3.3) | |

| Gender | Male | 44(33.8) | 69(53.1) | 9(6.9) | 2(1.5) | 6(4.6) |

| Female | 60(47.6) | 61(48.4) | 3(2.4) | 1(0.8) | 1(0.8) | |

| Depth | 1st degree | 10(66.7) | 4(26.7) | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | 1(6.7) |

| 2nd degree | 83(38.8) | 116(54.2) | 6(2.8) | 3(1.4) | 6(2.8) | |

| 3rd degree | 11(42.3) | 9(34.6) | 6(23.1) | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | |

| 4th degree | 0(0.0) | 1(100) | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | |

| Season | Spring | 22(32.8) | 38(56.7) | 3(4.5) | 1(1.5) | 3(4.5) |

| Summer | 33(43.4) | 36(47.4) | 4(5.3) | 1(1.3) | 2(2.6) | |

| Winter | 16(28.6) | 35(62.5) | 3(5.4) | 0(0.0) | 2(3.6) | |

| Autumn | 33(57.9) | 21(36.8) | 2(3.5) | 1(1.8) | 0(0.0) | |

| Total body surface area | <20% | 65(35.9) | 99(54.7) | 8(4.4) | 2(1.1) | 7(3.9) |

| 20–40% | 32(55.2) | 22(37.9) | 3(5.2) | 1(1.7) | 0(0.0) | |

| 40–60% | 7(46.7) | 8(53.3) | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | |

| >60% | 0(0.0) | 1(50.0) | 1(50.0) | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | |

Note. TBSA = total body surface area.

Management and Clinical Outcomes of Burn Victims

After their presentation to AaBet hospital, all patients had received wound care, 231 (90.2%) had obtained pain management, 179 (69.9%) had acquired antibiotics, 24 (9.4%) had received tetanus toxoid. Eighty-six percent of patients with a TBSA of 40% or more had received a fluid replacement.

Of the burn patients, 96 (37.5%) had undergone surgery at least once during their hospital stay. Of these, 51 (19.9%) had a skin graft, 48 (18.8%) had debridement, 22 (8.6%) had contracture release, 4 (1.6%) had undergone Escharotomies, 3 (1.2%) had undergone fasciotomies, 3 (1.2%) had undergone limb amputation, and two patients had disarticulation and digital wound repair. All three patients with chemical burns and 21 (61.5%) patients with flame burns had undergone surgery for a skin graft, and three (25%) patients with electrical burns had undergone surgery for limb amputation.

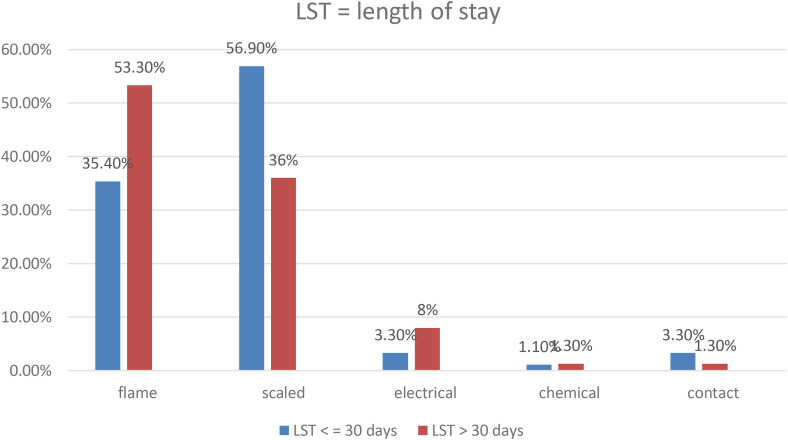

During their hospital stay, one-quarter of the patients (64) developed wound infection, while 36 (14.1%) developed contracture. The length of the hospital stay ranged from 1 to 164 days, with a mean of 24.73 days (22.42 SD). The majority of patients with first-degree burns had hospital stays of less than 30 days, while 57.7% of patients with third-degree burns had hospital stays of greater than 30 days (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Length hospital stay among burn injured children during the total study period from 2016 to 2020, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Most of the patients, 209 (81.6%), showed improvement at the time of hospital discharge with no or minor complications. While 21 (8.2%) left the hospital against medical advice. The remaining 18 (7.0%) were discharged with some form of disability or disability. Eight (3.1%) of the children died. Of these, three died within 24 h of their admission, and two of the burned children developed a wound site infection while in the hospital (Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinical Outcome of Burn Injury After 4 Years of Follow-Up in AaBet Trauma Center, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia from 2016 to 2020.

| Outcome | Improved | 88(42.1) | 104(49.8) | 7(3.3) | 3(1.4) | 7(3.3) |

| Disability | 7(33.3) | 13(61.9) | 1(4.8) | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | |

| Disfigured | 6(33.3) | 9(50.0) | 3(16.7) | 0 | 0 | |

| Death | 3(37.5) | 4(50.0) | 1(12.5) | 0 | 0 |

Associated Factors for Child With Burn Injury With Their Outcomes

In a binary logistic regression analysis, patients with associated injuries were 98.8% less likely to be alive than those without associated injuries (Table 4).

Table 4.

Factors Associated With the Clinical Outcomes of Children With Burn Injuries at the AaBet Trauma Center in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, From 2016 to 2020.

| Outcome final | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death | Alive | |||||

| Gender | Male | 2 | 128 | 0.313(0.062,1.578) | 1.384(0.141,13.610) | .781 |

| Female | 6 | 120 | 1 | |||

| The face/neck | Yes | 4 | 68 | 0.38(0.02, 1.53) | 0.65(0.64, 6.11) | .710 |

| No | 4 | 180 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Buttock/genitalia | Yes | 3 | 5 | 0.31(0.04, 1.35) | 0.5(0.09, 2.9) | .196 |

| No | 5 | 208 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Associated injury | Yes | 3 | 5 | 0.03(0.06, 0.18) | 0.012(0.01,0.27) | .006* |

| No | 5 | 243 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Fluid replaced | Yes | 5 | 67 | 0.22(0.02, 0.95) | 0.16(0.011, 2.49) | .189 |

| No | 3 | 181 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Surgery | Yes | 1 | 95 | 4.3(0.26, 5.88) | 2.17(0.61, 15.8) | .189 |

| No | 7 | 153 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Comorbidity | Yes | 2 | 19 | 0.24(0.07, 1.3) | 0.082(0.004, 1.854) | .116 |

| No | 6 | 229 | 1 | 1 | ||

| The length of stay | <=30 days | 4 | 177 | 2.4(0.07, 1.22) | 3.021(0.20, 43.95) | .085 |

| >30 days | 4 | 71 | 1 | 1 | ||

Note. 1:00: reference.

COR: crude odd ratio; AOR = adjusted odd ratio; CI = confidence interval.

*Significant at p-value < .05, **significant at p-value < .005.

Discussion

This study showed that the most frequently involved body part in pediatric burn injuries was the lower extremity (53.1%), in agreement with a multicenter retrospective study of both adult and pediatric populations in China by Tian et al. that showed that lower limbs were most frequently involved in burn incidents (Tian et al., 2018). In North Western Tanzania, Outwater et al. discovered that the trunk (57.3%) was more frequently involved in pediatric burn injury, followed by the head and face (69%) (Outwater et al., 2018). The difference might be due to differences in study design since this study is prospective. In this study, second-degree burns were the most common presentation of burn victims in this study hospital, covering 83.6%. Most of first degree burn has not visited in burn center. The reason might be that the first degree burn is mostly self-limited (cured). In agreement with this, a prospective study in Tanzania by Kabanangi et al. showed that 80.5% of the victims, both adults and children, had second-degree burns (Kabanangi et al., 2021).

In this study, the mean TBSA was 17.85 ± 13.58%. The majority of patients (70.7%) sustained less than 20% of TBSA. Compared to this study, Kabanangi et al. in Tanzania found 56.1% of patients had a TBSA of 15% or less, and another study in northwest Tanzania recorded a median TBSA of 14% (Kabanangi et al., 2021). Similarly, Mobayen et al. discovered a mean pediatric TBSA of 21.18 ± 12.29% in a retrospective study in southern Iran (Mobayen et al., 2021).

In this study, 8.2% of burn victims had co-morbidities, and more than half of them had seizure disorder before their current burn incident. At the time of their hospital presentation, 2.0% of the burn victims had an associated inhalational injury and 1.2% had a limb fracture. In line with this, F. Ready in Ethiopia found 5.7% of the burn victims had epilepsy, and in Tanzania, 2.5% of burn victims had a preexisting medical condition before their current burn incident. At the time of the hospital presentation, 1.5% of burn victims had associated inhalational injuries and 2% had fractures. 2.6% of associated inhalational burns were reported by Fellmeth et al. (2018).

Compared to other studies, in this study, patients received the least pre-hospital care, and very few of them (2.3%) had received first aid at home. In northwest Tanzania, 6.7% of patients received prehospital care (Kabanangi et al., 2021), whereas in North India, Lal & Bhatti et al. reported that 54.9% of pediatric patients received first aid before presentation to their center (Lal & Bhatti, 2017). In Beijing, Fellmeth found that 70.0% of patients had received pre-hospital care (Fellmeth et al., 2018). This may be related to the society's difference in knowledge toward first-aid practices and differences in study design since this study is prospective (Kabanangi et al., 2021).

In this study, more than 62% of the patients had received only conservative treatments; 90% of them had received analgesia, and all of them had wound care after their presentation, while 37.5% of the burn victims had undergone surgery. Similarly, a study performed in Tanzania showed that only 15% of the patients had undergone surgery, and the rest, 85%, had conservative treatments during their hospital stay. This study found that the mean hospital length of stay (LOS) was 24.73 days. In Tanzania, the mean LOS was 22.12 days (Sawe et al., 2022).

In this study, majority of the patients (81.64%) were discharged with minor or no complications. Similarly, a retrospective study at Mekele, Ethiopia, found that around 80% of the burn victims had minor or no sequelae when they were discharged from the hospital. A community-based survey by Gebreslassie & Esaias found 89.4% of the patients had no complications when they were discharged (Gebreslassie et al., 2018 ).

In this study, a mortality rate of 3.1% for pediatric burns was recorded. A retrospective cross-sectional study in Ethiopia by Gebreslassie et al. found 3.8% of pediatric deaths due to burn injury. Another community-based study in Mekele, by Ready et al. found a 1% mortality rate of burns in both the pediatric and adult populations. A cross-sectional study conducted by Peck found 6.0% mortality in both the pediatric and adult age groups (Peck, 2011; Ready et al., 2018). The difference might be due to differences in study design since this study is prospective. A study conducted by Williams et al. found a burn pediatric mortality rate of 2.8% in a 20-year review of a single pediatric burn center (Williams et al., 2009). Patients who had associated injuries were 98.8% less likely to be alive than those who had no associated injuries. A retrospective study of severe pediatric and adult burn patients by Ederer et al. (2019) showed that associated inhalational injuries were associated with increased mortality risk.

The Strength and Limitations of the Study

This study is a prospective follow-up study, thus, it could provide strong evidence for the outcomes of children with burn injury. Because this study was conducted at a pediatric age (14 years), it does not reflect the outcomes of burn injury in adults.

Implications of the Study

The study helps healthcare providers, policymakers, and programmers make interventions reduce burn injuries among children. The study was used as baseline information for researchers to conduct further action-based studies. It also provides clear evidence of the effects of burn injury and its adverse outcomes in children. Therefore, they can make an evidence-based decision for prevention and to promote recovery after injuries. In addition, it helps mobilize resources for managing burn injuries in the study area and throughout the country.

Conclusion

The highest proportion of burn incidents occurred in indoor settings. Scald and flame burns constituted the majority of the causes. In this study population, second-degree burns were the most common. Based on this study, the outcomes of the patients, the majority of them left of no or minor complications, and 3.1% had died. Most burned children had scald burns followed by flame burns. Patients who had burn-associated injuries were 98.8% less likely to be alive than those who had no associated injuries at all. The authors recommend that preventive measures be implemented at both the legislative and community levels. Preventive measures such as consistent community education about burns and their prevention, particularly, family members such as the mother, father, and nursery could be involved in community health education. Managing associated injuries, providing appropriate first aid in prehospital, using standard burn management protocol, and providing appropriate follow-up for the injured child might improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the data collectors, emergency coordinators, and all study participants for their contributions to the study's success.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: ST developed the proposal, analyzed the data, and wrote and interpreted the results. Professor AA drafted the manuscript, revised the proposal, checked the data, and revised the manuscript. OA and TB drafted and revised the manuscript. The authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding authors.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval and Consent to Participants: The ethical review board of the College of Health Sciences at Addis Ababa University approved this study (No. 2139 edu.net for ethical approval). It is certified that the study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Ousman Adal Tegegne https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7925-3411

References

- Adal O., Abebe A., Feleke Y. (2023). Occupational exposure to blood and body fluids among nurses in the emergency department and intensive care units of public hospitals in Addis Ababa city: Cross-sectional study. Environmental Health Insights, 17, 11786302231157223. 10.1177/11786302231157223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adal O., Emishaw S. (2023). Knowledge and attitude of healthcare workers toward advanced cardiac life support in Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia, 2022. Sage Open Medicine, 11, 20503121221150101. 10.1177/20503121221150101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adal O., Hiamanot Y., Zakir A., Regassa R., Gashaw A. (2023). Knowledge, attitude, and practice of nurses toward the initial managements of acute poisoning in public hospitals of Bahir Dar City, Northwest Ethiopia 2022: Cross-sectional study. SAGE Open Nursing, 9, 23779608231157307. 10.1177/23779608231157307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adane M. M., Admasie A., Shibabaw T. (2023). Risk factors of cooking-related burn injury among under-four children in northwest Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. Indian Pediatrics, 60(2), 119–122. 10.1007/s13312-023-2808-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Naimat I. A., Abdel Razeq N. M. (2023). Parents’ experience and healthcare needs of having a hospitalized child with burn injury in Jordanian hospitals: A phenomenological study protocol. The Open Nursing Journal, 17(1). [Google Scholar]

- Banga A. T., Westgarth-Taylor C., Grieve A. (2023). The epidemiology of paediatric burn injuries in Johannesburg, South Africa. Journal of Pediatric Surgery, 58(2), 287–292. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2022.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biru W. J., Mekonnen F. T. (2020). Epidemiology and outcome of childhood burn injury in Hawassa University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Hawassa, Southern Ethiopia. Indian Journal of Burns, 28(1), 51. 10.4103/ijb.ijb_28_19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ederer I. A., Hacker S., Sternat N., Waldmann A., Salameh O., Radtke C., Pauzenberger R. (2019). Gender has no influence on mortality after burn injuries: A 20-year single center study with 839 patients. Burns, 45(1), 205–212. 10.1016/j.burns.2018.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enkhtuvshin S., Odkhuu E., Batchuluun K., Chimeddorj B., Yadamsuren E., Lkhagvasuren N. (2023). Children's post-burn scars in Mongolia. International Wound Journal. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farzan R., Parvizi A., Takasi P., Mollaei A., Karkhah S., Firooz M., Hosseini S. J., Haddadi S., Ghorbani Vajargah P. (2023). Caregivers’ knowledge with burned children and related factors towards burn first aid: A systematic review. International Wound Journal. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Fellmeth G., Rose-Clarke K., Zhao C., Busert L. K., Zheng Y., Massazza A., Sonmez H., Eder B., Blewitt A., Lertgrai W., Orcutt M., Ricci K., Mohamed-Ahmed O., Burns R., Knipe D., Hargreaves S., Hesketh T., Opondo C., Devakumar D. (2018). Health impacts of parental migration on left-behind children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet, 392(10164), 2567–2582. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32558-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebreslassie B., Gebreselassie K., Esayas R. (2018). Patterns and causes of amputation in Ayder Referral Hospital, Mekelle, Ethiopia: A three-year experience. Ethiopian Journal of Health Sciences, 28(1), 31–36. 10.4314/ejhs.v28i1.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabanangi F., Joachim A., Nkuwi E. J., Manyahi J., Moyo S., Majigo M. (2021). High level of multidrug-resistant gram-negative pathogens causing burn wound infections in hospitalized children in Dares Salaam, Tanzania. International Journal of Microbiology, 2021, 1–8. 10.1155/2021/6644185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killey J., Simons M., Prescott S., Kimble R., Tyack Z. (2023). Becoming experts in their own treatment: Child and caregiver engagement with burn scar treatments. Qualitative Health Research, 10497323231161997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagziel T., Lopez C. D., Khoo K. H., Cox C. A., Garcia A. V., Cooney C. M., Yang R., Caffrey J. A., Hultman C. S., & Redett, R. J. (2023). Public perception of household risks for pediatric burn injuries and assessment of management readiness. Burns. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal S. T., Bhatti D. J. (2017). Burn injury in infants and toddlers: Risk factors, circumstances, and prevention. Indian Journal of Burns, 25(1), 72. 10.4103/ijb.ijb_14_17 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Long T. M., Dimanopoulos T. A., Shoesmith V. M., Fear M., Wood F. M., Martin L. (2022). Grip strength in children after non-severe burn injury. Burns, 49(4), 924–933. 10.1016/j.burns.2022.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoughlin E., McGuire A. (1990). The causes, cost, and prevention of childhood burn injuries. American Journal of Diseases of Children, 144(6), 677–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobayen M., Zarei R., Masoumi S., Shahrousvand M., Mazloum S. M. H., Ghaed Z., Rahimzadeh N. (2021). Epidemiology of childhood burn: A 5-year retrospective study in the referral burn center of Northern Iran. Caspian Journal of Health Research, 6(3), 101–108. 10.32598/CJHR.6.3.8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Outwater A. H., Thobias A., Shirima P. M., Nyamle N., Mtavangu G., Ismail M., Bujile L., Justin-Temu M. (2018). Prehospital treatment of burns in Tanzania: A mini-meta-analysis. International Journal of Burns and Trauma, 8(3), 68–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson K. N., Beyene T. J., Lehman K., Verlee S. N., Schwartz D., Fabia R., Thakkar R. K. (2023). Evaluating effects of burn injury characteristics on quality of life in pediatric burn patients and caregivers. Burns. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peck M. D. (2011). Epidemiology of burns throughout the world. Part I: Distribution and risk factors. Burns, 37(7), 1087–1100. 10.1016/j.burns.2011.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ready F. L., Gebremedhem Y. D., Worku M., Mehta K., Eshte M., GoldenMerry Y. L., Nwariaku F. E., Wolf S. E., Phelan H. A. (2018). Epidemiologic shifts for burn injury in Ethiopia from 2001 to 2016: Implications for public health measures. Burns, 44(7), 1839–1843. 10.1016/j.burns.2018.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawe H. R., Milusheva S., Croke K., Karpe S., Mfinanga J. A. (2022). Pediatric trauma burden in Tanzania: Analysis of prospective registry data from thirteen health facilities. Injury Epidemiology, 9(1), 1–11. 10.1186/s40621-021-00367-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian H., Wang L., Xie W., Shen C., Guo G., Liu J., Han C., Ren L., Liang Y., Tang Y., Wang Y., Yin M., Zhang J., Huang Y. (2018). Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of severe burn patients: Results of a retrospective multicenter study in China, 2011–2015. Burns & Trauma, 6. 10.1186/s41038-018-0118-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiruneh C. M., Belachew A., Mulatu S., Emiru T. D., Tibebu N. S., Abate M. W., Nigat A. B., Belete A., Walle B. G. (2022). Magnitude of mortality and its associated factors among burn victim children admitted to South Gondar zone government hospitals, Ethiopia, from 2015 to 2019. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 48(1), 1–8. 10.1186/s13052-022-01204-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toolaroud P. B., Nabovati E., Mobayen M., Akbari H., Feizkhah A., Farrahi R., Jeddi F. R. (2023). Design and usability evaluation of a mobile-based-self-management application for caregivers of children with severe burns. International Wound Journal. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams F. N., Herndon D. N., Hawkins H. K., Lee J. O., Cox R. A., Kulp G. A., Finnerty C. C., Chinkes D. L., Jeschke M. G. (2009). The leading causes of death after burn injury in a single pediatric burn center. Critical Care, 13(6), 1–7. 10.1186/cc8170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]