Abstract

Objective:

In March 2020, restrictions on in-person gatherings were introduced due to the COVID-19 pandemic, requiring alcohol use disorder (AUD) recovery resources to migrate to virtual platforms. This study investigated how these restrictions impacted recovery attempts and explored participant experiences with virtual resources using a qualitative approach.

Methods:

Participants attempting recovery from AUD (N=62; M age = 48.2; %F=53.2; 71% White) completed virtual semi-structured interviews from July 2020 to August 2020 on their experience during the COVID-19 lockdown, impacts on recovery, and experiences with online resources. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using a thematic coding process.

Results:

Three overarching themes were identified: Effect on Recovery, Virtual Recovery Resources, and Effect on General Life. Within each overarching theme, lower-order parent themes and subthemes reflected varied participant experiences. Specifically, one group of participants cited negative impacts due to COVID-19, a second group reported positive impacts, and a third group reported experiencing both positive and negative impacts. Participants reported both positive and negative experiences with virtual resources, identifying suggestions for improvement and other resources.

Conclusions:

Findings suggest that while individuals in AUD recovery experienced significant hardships, a proportion experienced positive impacts as well, and the positive and negative consequences were not mutually exclusive. Additionally, the results highlight limitations of existing virtual resources.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, qualitative methods, alcohol use disorder, recovery, virtual resources

Introduction

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, public health restrictions related to social distancing were introduced in an attempt to reduce rates of COVID-19 contraction and transmission (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020; Polisena et al., 2021). As a result, highly utilized mutual help organizations (MHOs) such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), Self Management and Recovery Training (SMART), and other alcohol use disorder (AUD) recovery resources prohibited in-person meetings and migrated to an online setting. A key aspect central to many of these recovery services is offering an opportunity for change in social support networks (Ashford et al., 2021; Kelly et al., 2012; Moos & Moos, 2006; Pierce et al., 1996). For many, these recovery support resources and the social connections they facilitate are crucial to recovery. With the cancellation of in-person services came a cancellation of small, informal social interactions that help foster connection and social support, which may be integral to recovery maintenance. Therefore, on top of the stress of living through a global pandemic, those recovering from an AUD were hit with additional stressors related to maintaining recovery through the pandemic, all while much relied upon services remained unavailable in an in-person format.

Several studies have examined changes in alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., Alpers et al., 2021; Callinan et al., 2020; Kilian et al., in press; Schmits & Glowacz, 2020). Additionally, literature suggests that virtual AUD recovery resources can be effective (e.g., Elison et al., 2017; Campbell et al., 2016), and recent articles have addressed the importance of offering virtual recovery resources during the COVID-19 pandemic (Bergman & Kelly, 2021; Bergman et al., 2021; Krentzman, 2021). Further, a number of articles have highlighted the struggles that those with an AUD or those attempting recovery from an AUD may face during COVID-19 (Jemberie et al., 2020; Sugarman & Greenfield, 2021; Volkow, 2020). However, to date, there is limited research that has actually engaged with these populations to explore and report participant-driven perspectives on how COVID-19 has impacted them.

Two studies have used qualitative methods to investigate how COVID-19 has broadly impacted those with a substance use disorder or AUD (DeJong et al., 2020; Seddon et al., 2021). However, neither of these studies examined the impacts of COVID-19 on recovery, specifically. Additionally, while Seddon and colleagues examined participant experiences with virtual resources and found generally negative feedback, this study was conducted with a sample of older adults (aged 55 and older). It is likely that younger samples may have differing perspectives and experiences with online resources (Seddon et al., 2021). The limited research available leaves participant-driven perspectives on the impact of COVID-19 on recovery, and experiences with virtual resources an important and scantly addressed area of work.

The purpose of the study was two-fold. First, in a sample of individuals participating in ongoing studies of AUD recovery mechanisms, this study sought to examine patterns in how restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic have impacted individuals’ attempting recovery from an AUD. Secondly, the study sought to examine patterns in the perceived utility, user experience, and benefits of virtual resources. Collectively, the study sought to understand the various impacts of the pandemic on AUD recovery directly as described by individuals who recently made a recovery attempt. Given the exploratory nature of this study, limited previous research on this topic, and interest in understanding the participant experiences as relayed by themselves, qualitative methods were employed to understand experiences across participants more deeply.

Methods

Participants

Participants (N=62) in this qualitative study were recruited from a quantitative study investigating the impact of COVID-19 on recovery from alcohol use disorder (AUD) that was added to two ongoing research projects in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada and Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America, both of which focused on understanding the mechanisms underlying change in AUD recovery. Nineteen participants in this study were from Hamilton, and the remainder (43) were from Boston. Results from the quantitative study are in a separate report. This study was not pre-registered and thus findings should be considered exploratory. All participants were at least 18 years old, met DSM-5 criteria for an AUD, and were actively engaged in a recovery attempt (either formally or informally). The majority of participants (75.8%) in the present study were at least three months into their recovery attempt and had spent on average about 269 days in recovery. Interviews took place between July and August of 2020. Participant characteristics were similar across sites in many key demographic and substance use variables. However, there were site differences in participant ethnicity, median income, and average percent drinking days. See Table 1 for more detailed participant characteristics and Table 1 in Supplemental Materials for more information on site differences.

Table 1:

Participant Characteristics (N=62)

| Mean (SD)/Median/% | |

|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | |

| Sex (%F) | 53.2 |

| Age | 48.2 (12.1) |

| Years of Education | 14.7 (2.5) |

| Income (Median) | 15k-<30k |

| Race (%) | |

| White or Caucasian | 71 |

| Black or African American | 21 |

| Other | 8 |

| Drinking and Substance Use Characteristics | |

| AUD symptoms | 6.4 (3.7) |

| Days in recovery | 268.7 (120.4) |

| % abstinent in last 90 days | 32.3 |

| Average % days drinking pre-COVID (%) | 29.9 (31.3) |

| Average % days drinking during COVID (%) | 28.2 (32.2) |

| % with at least 1 heavy drinking day in last 90 days | 63 |

| Other substance use (% yes) | 56.5 |

| Cannabis | 32.3 |

| Sedatives, hypnotics, or anxiolytics | 3 |

| Opioids | 3 |

| Stimulants | 11 |

| Cigarettes | 44 |

Procedures and Assessments

Participants from the quantitative COVID-19 study who indicated interest in a follow-up qualitative interview were contacted to take part in the semi-structured virtual interview with a trained research assistant (interview included in Supplemental Materials). Interviews were conducted via Zoom or phone and were audio recorded. The interviews focused on four major topics: 1) personal experience during the COVID-19 lockdown period (defined as beginning on March 24th 2020, the date that all non-essential businesses closed in the Boston and Hamilton areas); 2) impact of restrictions on general life, recovery attempts, and relationships; 3) any coping mechanisms utilized to support recovery and cope with the pandemic; and 4) experiences using virtual recovery resources (i.e., comparisons to in-person resources, barriers to accessing these resources, and whether they had any recommendations for how available resources could be improved). When warranted, individualized follow-up questions were asked to further explore themes that emerged throughout the interviews. The average interview length was 36 minutes (SD = 14 minutes, minimum = 15 minutes, maximum = 74 minutes). All participants provided informed consent, and all procedures were approved by both the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board and the Partners HealthCare Institutional Review Board at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, USA. Interviews may be made available to qualified investigators upon request.

Data Analysis

First, interviews were transcribed verbatim using the TranscribeMe transcription service and were individually reviewed by research staff to ensure accuracy. Then, Dedoose software was used for coding and data analysis. Each transcript underwent an iterative, thematic coding process completed by trained researchers. Seven researchers were paired in groups of two or three, where each transcript was first coded independently. Then, researchers reviewed the coded transcripts in their groups. In the event that codes did not match, the researchers discussed until they reached agreement. If agreement was not met, the researchers would bring the issue forward to the entire coding group, where it was then discussed until agreement was met. During the code development process, interview questions were used as a guide to develop overarching themes (highest level), parent themes, and sub-themes (most granular) following existing practices (Cope, 2016; Saldana, 2009). Throughout data analysis, the coding scheme developed and expanded until no further themes or subthemes were identified. In total, there were three iterations of code development. Finally, transcripts were reviewed to ensure all excerpts were coded according to the final coding scheme. The coding process resulted in 101 codes, total. Following a visual review of code frequency, researchers decided that to be considered a theme, codes were required to meet an application frequency threshold of at least 75 applications, or address an integral research question. This cut-off resulted in the identification of three overarching themes (most broad), seven parent themes, and 16 subthemes (most granular). The final step was to conduct a theme co-occurrence analysis. This analysis examined the number of times that themes were coded together in the same excerpts. This provided a deeper understanding of how themes related to one another and naturally co-occurred while participants spoke. Two co-occurrence analyses were conducted: one among parent themes, and one among subthemes.

Results

Overarching Themes

Figure 1 provides a visual of the resulting thematic structure. The three overarching themes revealed in data analysis were: Effect on Recovery, Recovery Resources, and Effect on General Life. Effect on Recovery captured how participants’ recovery attempts were impacted by COVID-19 and the related restrictions. It included three parent themes and no subthemes. The second overarching theme, Recovery Resources captured participants’ experiences with virtual recovery resources. It included two parent themes with three subthemes each. The third overarching theme, Effect on General Life, captured how participants’ lives were impacted by COVID-19 in a wider variety of domains. This theme included two parent themes and 10 subthemes. The following results characterize the parent themes and subthemes, including information on theme presence (percent of transcripts to which the theme was applied) and theme frequency (number of applications across transcripts). For additional quotes in each subtheme, see Tables 2, 3 and 5. For more information on application frequency among parent themes and sub-themes, see Figures 2 and 3, respectively.

Figure 1:

Overall Thematic Structure

Note: Ovals reflect overarching themes (highest order theme), circles represent parent themes, and rectangles represent subthemes (most granular themes)

Table 2:

Presence of Parent Themes Nested Within the Overarching Effect on Recovery Theme

| Parent Themes | % | Example Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Negative Effect on Recovery | 77.4 |

P13-061: “ … we get released and obviously we have to isolate, right, quarantine. So my mind was going crazy and I went back to drinking. I went two months without drinking and then went right back to drinking, very depressed, very down. I actually got my first charge ever in my life. I got a DUI with that accident. So yeah, it has not been good at all.” P158 SM 368: “It was affecting me a lot. Just drink, drink, drink. You’re home, you’re by yourself, there’s nothing else to do, nobody’s out there.” |

| Changes to Recovery Strategies | 61.3 |

P11-027: “I normally drive women from Womankind [treatment service] to AA meetings in the evenings and then drive them back, and I haven’t been able to do that either, so. …it was a huge part of my recovery because I knew I had to be sober, and I knew I was helping other people by taking them to a meeting… so that was a huge toll on me, to be honest.” P158 (SM 368): “It tried to kill me from staying in recovery because when it hit, it shut everything down. And so three weeks later, I got hooked up with the Zoom so I could get my meetings. And that helped a lot.” |

| Positive Effect on Recovery | 51.6 |

P72 (AA 2074): “I think it made it easier to recover because it was like living a normal life but with some kind of training wheels because you go out, you can go places but all the places with alcohol are shut down… So it was like living in a dry society for a little bit. And made building sobriety easier I think cause it was like less temptation around it.” P13-030: “In terms of drinking, like I said, it was kind of a blessing because there weren’t the social events I had to worry about. And at the time, patios at bars weren’t even open. I mean, it sucked a little. …But social wise, like I said, it’s been kind of beneficial from the temptation, you know?” |

Note: %= the percentage of total transcripts that the theme was applied at least once.

Table 3:

Presence of Parent and Subthemes Nested Within the Overarching Recovery Resources Theme

| Parent Theme and Subthemes | % | Example Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Experiences with Virtual Resources | 93.5 | |

| Comparison to In-Person Resources | 77.4 |

P11-006: “How is that even going to work if I can’t physically see and talk to other people who are going through something similar to myself? I mean, going online and stuff like that is great on video, but it’s not the same as seeing somebody in person. I get a lot from the actual face to face interaction as opposed to just something online. I think everybody probably does but it’s a whole different thing and, if, when you get to hear it, some of these stories, for example, in person, as opposed to online where you can just kind of turn it off or pause it. In-person, you can obviously not do that. So it’s just more real to me when it’s in-person.” P13-044: “And I feel like because it’s online, yeah, you don’t have to give away two or more hours of your time to drive to and from the meeting. Basically, you have more time in the day to do what you got to do, and then you can do more meetings that way as well. You can kind of-- in the conference ones, you can just kind of put it on and listen to it like a podcast, some of that stuff” |

| Positive Experiences with Virtual Resources | 67.7 |

P71 (AA 2073): “I actually find the benefit of being able to be on more-- I’m not waiting for a 6:00 PM Wednesday meeting. I can be online on Zoom anytime, or I actually have more access to people, because people aren’t either working or they’re at home or they’re not as busy. So I actually find that I can have more meetings, more access to people than I did before social isolation.” P13-063: “Yes. Because people from different places in the world have different cultural experience and different ways of thinking. And it’s amazing to see that AA is all over the world and people are benefiting from something that started from one alcoholic helping another. There’s millions of people in AA in the world. So that’s been helpful. I like international because I get a different perspective-- like if you’re in small town you’re listening to the same people, you’re going to get the same perspective. But people from say New Zealand or people in Holland or France, or Australia, they have a different take on life. So it’s nice to have that. Its refreshing. Different cultural beliefs and ways of being so. I’ve been learning from that too which is great” |

| Negative Experiences with Virtual Resources | 43.5 |

P13-077: “I tried a few times. I obviously didn’t try very hard but I just couldn’t find meetings that I felt involved in, I guess… I found it very hard and I just didn’t try very hard to find the meetings because I really dislike virtual meetings, especially with something awkward.” P12-009: “Well, I found they were not as much sharing. Because I like meetings where I felt more intimate. …I’m more of a face-to-face guy. I like to read someone’s face and look in their eyes and hear their voice and man your-- and in these Zoom meetings, one person does a lot of talking, and some people are just, “Hi.” “Hi.” “Bye.” “Bye.” …I find everyone is kind of hesitant to talk on the phone, you don’t really see them on Zoom. And I just didn’t like it.” |

| Suggestions and Barriers | 95.2 | |

| Recommended Improvements | 72.6 |

P12-009: “I think if they have fewer people. I mean, in some meetings there are like 50 people, and it just becomes-- it was too big…online meetings should be small amount of people to make sure everybody shares. They should have more rotating-- people involved. Some people we were trying to-- taking over and it was kind of so-and-so’s and so-an-so’s meeting, you know what I mean?” P12-009: “Well, yeah, maybe they could have opened of a library with cubicles where they are six feet apart. And some people calling like, “I don’t know how to do online meetings on my phone, and I don’t have the capabilities, I have an old phone, I don’t have Wifi.” …So I think just maybe-- I mean, some government buildings that were separated, but doesn’t allow--a lot of people don’t have wi-fi, and they don’t have data. And then can’t get on a meeting. Everybody presumes the whole world is-- I mean, kids have more access these days than some people that are addicts, they don’t have the money, right?” |

| Requested Resources | 58.1 |

P97 (SM 95): “Like I said, I know a few people who have passed since this all happened, and I mean, it’s their fault that they chose to relapse and use. I’m just saying that not having access to in-person stuff or the certain services. There are certain things that should continue on like recovery centers, recovery meetings. They should have continued on. None of them should have stopped, none of them should stop meeting in person because that trumps quite frankly, anything else going on right now.” P67 AA 2069: “I just make it more inclusive for new beginners and making it very clear on how there’s ways right? Like I just mentioned, either put like an email or a phone number at the end of the meeting like say, “Okay this is the end of the meeting. I’m gonna share my screen right now. It’s going to have my phone number and my email if anybody needs anything and they feel too scared to talk, reach out here.” Right? Just something so then that person can be like, “Okay.” They’re going to write down their phone number/email and reach out. I think would be the biggest help.” |

| Barriers to Access | 54.8 |

P13-044: “…more to the other people. If they like the library or the hospital could open up a computer lab or they could have people come in and allow them to do AA meetings that way. Making them accessible to people who don’t have access to any sort of screen time, screens.” P61 AA 2063: “I’m really lucky because I have high-speed Wi-Fi and I have a phone and I have a laptop. And I know how to use the technology because I’ve worked remotely before. I mean, that’s the other thing about these Zoom calls with people who are just not very tech-savvy, I feel terrible for them. They just can’t get it and it’s really hard for them to participate too” |

Note: %= the percentage of total transcripts that the theme was applied at least once.

Table 5:

Presence of Parent and Subthemes Nested Within the Overarching Effect on General Life Theme

| Parent Theme and Subthemes | % | Example Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Impact on Daily Life | 100 | |

| Adaptive Coping Mechanisms | 100 |

P169 SM 446: “In terms of missing the gym, I ended up buying some workout equipment from my house and then doing Zoom workouts with my friends or going on runs with my neighbors and everything. And in terms of just hanging out with friends, once again, doing things over Zoom, like playing games online with my friends, and just switching everything from in-person to online, making that big step.” P71 AA 2073: “…Recovery literature. I do read a lot more of the program literature than I had before. It’s sort of like the big book. There’s some Hazelton books. There’s early sobriety things. And then I started taking advantage of a lot of autobiographies of women in recovery and things like that, so I do a lot more reading of resources and stuff.” |

| Routine | 98.4 |

P132 (SM285): “What I’ve had has been either taken away or greatly limited. I go to soup kitchens all the time. Right now, we stand in line and get a meal and go. It used to be a sit-down thing in a hall. I used to go to the hospital cafeteria and get a meal. Nope. That’s still closed to the public.”

P12-009: “Before COVID you had a structure of today I’m going to do this, tomorrow I’m doing this. And you were being held accountable for that. Are there--?Right. And you have self-accountability and third-party accountability. You know what I mean? Right. And I look in the mirror and say, “I’m not going to use.” Then COVID-19 like, “Well, who cares anyways.” Right? And this sort of thing-- the world’s-- it felt like an apocalypse that one part of the year.” |

| Technology Use | 91.9 |

P133 (SM 286):

“I’m just on there 24/7 … I’m on there a lot, a lot more than when I was out doing things and I had a social life and a life outside of COVID. And I feel stuck, I feel like everything is through the phone and if I don’t have my phone, I can’t find my phone, my phone’s not charged, then my hand is freaking out” P119 SM 182: “Oh my God, I’m on the phone all the time. I’m constantly on Facebook, Instagram, constantly reading all of my emails like crazy. I have a lot of news apps on my phone too. I read the news. I read the news through Facebook too to come to find out it’s fake news. …like I said, I’m always on the phone. I’m always looking up stuff. I’m always looking what’s on sale at Zulily, what’s on sale at Walmart, what’s on clearance at Groupon. I got them all.” |

| Poor Mental Health/Mood | 85.5 |

P11-027: “COVID-19 affected my mood by-- because I have no immune system, I can’t go anywhere. So it gave me-- my anxiety levels, my depression levels, everything went skyrocketing through the roof. So I was not feeling myself or very good, at all.” P148 SM 348: “Oh, yeah. I’ve been pretty-- extremely depressed, but-- yeah. I tried reaching out and getting help a few times, but it didn’t really… Mental health resources are spread pretty thin right now, so yeah, I guess it has intensified my depression.” |

| Isolation | 74.2 |

P13–052: “I just felt more isolated, more time to think. There wasn’t really anything to do or keep me active. I walked a bit, but it still doesn’t fill my days”

P44 2045: “Well, I’ve basically been shut in. I stay in unless I have to go shopping with my wife. …And so we stay in the house. We cook. We watch movies. We watch television. We watch CNN.” |

| Employment | 56.5 |

P11-027: Work is it all. I own my own business, so all my employees were out of work because of COVID. I was getting no money coming in. It was a huge, huge toll on me.”

P95 SM84: “My work cut me from 40 hours to 20 hours during the COVID because of exposure and then the client went in the hospital and came back home on hospice. And like I said, she passed. So it was kind of very difficult financially and emotionally” |

| Negative Experiences with Societal Response to Virus | 50 |

P58 AA 2060:

“I didn’t run out and try to buy all the toilet paper and all the water out of the store, and a lot of people did that. And it was so frustrating because those people are really just looking out for themselves, and they don’t think that their neighbor needs toilet paper and water too. It was just kind of frustrating. You can see where people are really at when it comes to those kind of situations. And they’re just really only thinking about themselves.” P58 AA 2060: “Anger at people who don’t take it seriously and are having these-- they’re protesting having to wear masks. I mean, that affects my mood. That makes me both angry and sad… I wish they would regulate more, and enforce it when people aren’t wearing masks. There’s no ticket.” |

| Impact on Relationships and Social Life | 100 | |

| Friend and Family Substance Use | 93.5 |

P11-027: “I have talked to multiple of my girlfriends and people from AA that say COVID has also made them re-drink and they had two or three or four years sober. So it’s really affected the AA community for sure.” P50 AA 2051: “Most of the homeless people, they panhandle. They have to get change to get money to drink for a day. So there’s a lot of and most of my friends live in the train station. That’s where they stand and ask for some money or whatever. But people are not working, so they don’t get that money cause people don’t use transportation. So they’re drinking less I would say.” |

| Negative Impact on Relationships | 82.3 |

P11-027:

“I’m not as close with any of my friends as I was before COVID. Because of COVID, I haven’t seen my friends when I was living at my parent’s house because they don’t want me going anywhere to get something and come back here with it. And then, when I lived by myself, my parents didn’t really want me-- they didn’t want me in contact with anyone either coming back to their house too, so. Yeah. It really affected my family and friends. I felt very isolated.”

P148 SM 348: “Yeah. I kind of fell out of touch with a lot of my friends, and a lot of them just-- their moods changed too, so it’s kind of hard to talk to them after this started. And. Yeah. I know a lot of my friends ended up going sober, not that I have that many friends. I guess, some of them took it as an opportunity to stop drinking.” |

| Positive Impact on Relationships | 56.5 |

P13-044: “Like doing all my meetings. I feel really close with that group of ladies that I told you about in the morning meetings. I haven’t even met them and I feel really close with them. So yeah, it’s helped that way”

P12-062: “Yes. It’s brought our family closer, and [my wife] and myself, …my closest relationship, my dearest friend, we’ve learned a lot. Lots of times to talk and not to talk, and this has kind of forced us to really take heat of that because we wouldn’t-- we’re long married people. …So I would say it was a good thing. It’s brought us closer, my family, my sisters.” |

Note: %= percentage of total transcripts that the theme was applied in least once.

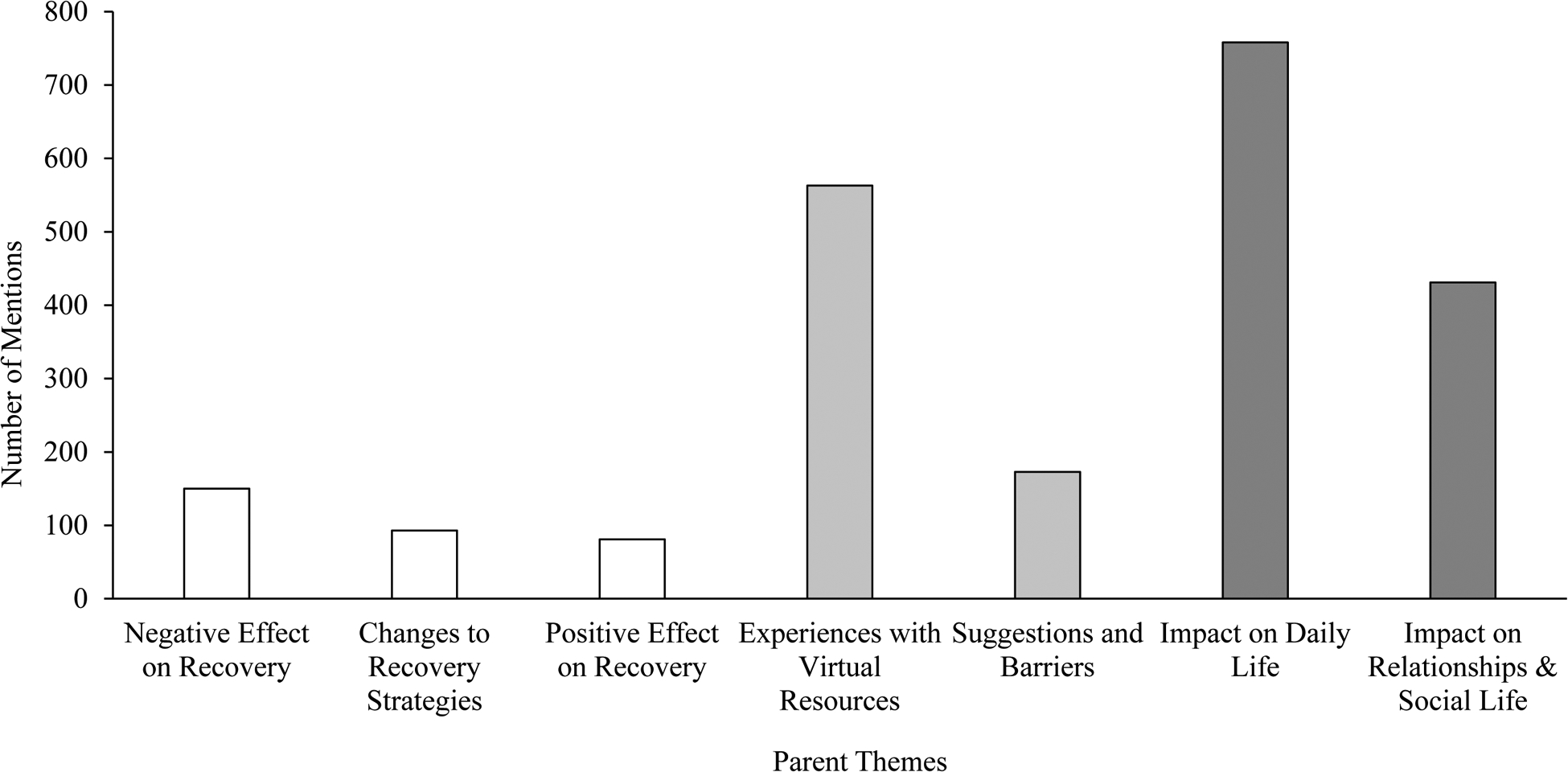

Figure 2:

Number of Times Parent Themes Were Mentioned Across All Transcripts

Note: Bars match the colour of the overarching themes that the parent themes are nested within. White = Effect on Recovery, light grey = Recovery Resources, dark grey = Impact on General Life.

Figure 3:

Number of Mentions of Subthemes Nested Within the Recovery Resources and Impact on General Life Overarching Themes

Note: Bars match the colour of the overarching themes that the subthemes are nested within. Light grey = Recovery Resources, dark grey = Impact on General Life.

Effect on Recovery

The theme Effect on Recovery was present across all transcripts and included three parent themes: Negative Effect on Recovery, Changes to Recovery Strategies, and Positive Effect on Recovery.

Negative Effect on Recovery was present among 77.4% of transcripts. This theme was applied when participants spoke about how COVID-19 negatively impacted their recovery attempt. Participants commonly expressed sentiments that isolation and an inability to develop a new social circle has negatively impacted their recovery:

“I can’t do those lifestyle changes that I needed to do in order to create a new circle or a new life or foundation. I’m just kind of stuck inside and all I have is my mind and my mental ability to stop myself from drinking”.

(P13-077)

In another example, a participant reflected upon how the combination of boredom and alcohol remaining widely available while other services and businesses remained closed would result in drinking : “Well, obviously the LCBO [Liquor Control Board of Ontario] stayed open so getting alcohol was not a problem. And I couldn’t keep myself busy because there was nothing to do. So just drinking would be, unfortunately, the only option” (P13–061). The second parent theme, Changes to Recovery Strategies was present in 61.3% of transcripts. This theme reflected how participants adapted and actively changed strategies to manage their recovery during the COVID-19 lockdown. Some participants cited making the switch to virtual recovery resources as a strategy change, while others cited an active change in mindset, whereby participants boldly decided to treat the pandemic as an opportunity to focus on and prioritize their recovery. For example, one participant said:

“I guess my mindset was like, ‘This is a pandemic. This is something we can’t control. Everything is going to change right now and I can take it as an opportunity to do something differently.’ So I’ve been telling people I almost treated it like an inpatient hospitalization, like, I can’t go anywhere. All I have is access to Zoom meetings and recovery, and I’ll take advantage of that”.

(P71 AA 2073)

The third parent theme was Positive Effect on Recovery. It was present across 51.6% of transcripts. This theme identified when a participant spoke about how COVID-19 resulted in a positive impact on their recovery attempt. Some participants stated that the move to virtual resources allowed them to attend more meetings which they have found to be helpful, or that the pandemic has allowed them the space and opportunity to slow down and focus on their recovery. For example, one participant said:

“I believe for me it slowed me down and it helped me focus on my recovery, because I was in the house. So all I had to do was read, and online meetings and stuff like that and talk on the phone. So I’ve benefited ”.

(P75 AA 2077)

Further, many participants reported that the social restrictions and lack of social events removed situations in which temptation was likely to occur, making it easier to abstain from drinking.

“I mean, it’s just-- right now it’s just still an opportunity for me to have more meetings. And I don’t feel the social pressure of getting together with friends who are still drinking to even go out to dinner and be around a bar or a potential of ordering something, which is kind of a relief in early recovery of, I don’t have to figure out and say no.”

(P75 AA 2073)

Overall, findings from this overarching theme emphasized that while a large proportion of participants experienced negative effects on their recovery (77%), in part due to isolation and boredom, positive impacts still did emerge, with just over half of participants citing a positive impact on their recovery. Participants spoke of how the opportunity to attend more meetings, focus on their recovery, and temptation reductions due to lack of social events were key factors that helped their recovery. Additionally, participants reported flexibility in actively changing strategies to manage their recovery throughout the pandemic.

Recovery Resources

The overarching theme of Recovery Resources captures when participants spoke about anything regarding virtual recovery resources. Two parent themes emerged - Experiences with Virtual Resources and Suggestions and Barriers. The Experiences with Virtual Resources parent theme included three subthemes related to participants speaking about their experience with virtual recovery resources since the COVID-19 pandemic. Subthemes that emerged in this parent theme were: Comparison to In-Person Resources, Positive Experiences with Virtual Resources, and Negative Experiences with Virtual Resources. The first subtheme, Comparison to In-Person Resources was present in 77.4% of transcripts and was applied when participants compared and contrasted their experiences with virtual resources with in-person resources. Some participants expressed that they liked that online resources were more available and not associated with logistical hassles (driving to and from meetings, availability to log into a meeting at any time of day), while others focused on differences related to the feelings of not being in a physical space:

“It’s different because you don’t have the personal contact. You don’t have the hugs, the coffee, the socializing before the meeting, after the meeting. But we find a way to do it even through Zoom. So the only difference is you just don’t-- you’re not sitting next to no one. You don’t have the physical contact. That’s it”.

(P715 AA2077)

The Positive Experiences with Virtual Resources subtheme was present among 67.7% of transcripts. This theme was applied when participants spoke about their positive experiences using virtual recovery resources. Participants reported that they felt resources were necessary for their recovery, and that they leaned on resource utilization to help them through the pandemic. They reported feeling a greater accessibility to meetings because they could find one at any time of day or night, and the benefits of being exposed to new perspectives through attending meetings from around the world. One participant said:

“It’s been really cool going to meetings all over the world. It’s almost easier to message people, ask for their numbers, for me anyway, via the chat function. It’s allowed me to build more of a fellowship in that sense since I’m really shy in-person. It’s kind of allowed me to work more on my recovery in the sense of my steps because I can just hop on a meeting, or if I’m struggling I can just hop on to a meeting at any time. I don’t kind of need to wait for the meeting to start, the drive down there. It almost gives you no excuse to not go to meeting because they’re available literally any time, 24/7.That’s great.”

(P13–030)

The Negative Experiences with Virtual Resources subtheme was present in 43.5% of transcripts. Here, participants spoke about any negative experiences they had with virtual resources. Participants reported frustrations around the difficulty of making personal connections through online channels, lack of meaningful conversations online, difficulties using technology, and issues with concentrating on meetings while attending from home. One participant said: “Online stinks. And also, it’s the same. I don’t feel like it’s very real. You’re not around people. You can’t really read people-- not read them, but I mean understand 100% where they’re coming from” (P133 SM 286).

The second parent theme, Suggestions and Barriers, captured participants speaking about how resources could be improved to better suit their needs, resources they wish they had access to, and barriers they encountered to accessing or using available resources. This parent theme included three subthemes: Recommended Improvements, Requested Resources, and Barriers to Access. The first subtheme, Recommended Improvements, was present in 72.6% of transcripts and spoke mainly to participants’ suggestions on how to improve upon current resources. Five categories regarding specific improvement suggestions emerged. These categories are not considered themes as they did not meet the application frequency threshold. First, participants reported Accessibility as a category for improvement. They expressed concerns about how those without stable internet, a computer, or other devices might not have access to resources despite needing them. Second, participants reported Advertising as an area for improvement. They reported a lack of awareness about online resources and how available resources should be better advertised to increase visibility. The third category of recommended improvements was Meeting Structure, which captured participants’ reflections on how the meetings themselves could be improved. Some participants highlighted that they were uncomfortable speaking when many meeting members had their cameras off, or that there was not enough time for everyone to speak when meetings were too large. The fourth category was Technological Support, which refers to participants’ requests that there be technological support to help attendees access meetings and resources when glitches and problems with technology arise. Finally, participants expressed a request for a Central Resource, which reflects participants suggestions that there be a central hub where links to meetings, webpages related to recovery, and other recovery resources are posted.

The second subtheme, Requested Resources, spoke to participants’ requests for additional resources they would like to access. 58.1% of participants identified requested resources. Three categories regarding types of requested resources emerged. These categories and are not considered themes as they did not meet the application frequency threshold. The first category was In-Person Resources, which highlights that despite many positive experiences with virtual resources, participants still longed for some offering of in-person resources throughout the pandemic. The second category was Additional/Other Meeting Options, which refers to participants requests for a greater volume of meetings and more varied types of meetings. Finally, the One-on-One Aspect category refers to participants’ requests for a resource that incorporates a one-on-one therapeutic connection. Some participants spoke about how they missed individualized connection, and that having a one-on-one resource may help them maintain accountability in managing their substance use and recovery. For quotes related to each of these categories under the Recommended Improvements and Requested Resources subthemes, see Table 4.

Table 4:

Presence and Application Frequency of Recommended Improvements and Requested Resources Categories

| Feedback Categories | % | Frequency | Example Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recommended Improvements | 72.6 | 82 | |

| Accessibility | 30.6 | 23 |

P13-044: “I mean, I think allowing them to be more public… if they like the library or the hospital could open up a computer lab or they could have people come in and allow them to do AA meetings that way. Making them accessible to people who don’t have access to any sort of screen time, screens. Yeah. I think that would be number one” P13–028: “I think that there’s still-- I feel that there are still a lot of people out there who have not been able to access these resources because for whatever reason that they don’t have the technology or that’s a barrier for them somehow. But yeah, I think that-- I definitely feel we don’t have 100% attendance. And so I think that has a lot to do with the technology.” |

| Advertising | 21 | 13 |

P169 (SM 446): “I think now especially because a lot of people, they’re using social media and they’re spending a lot more time on social media, just targeting them through advertisements on that, maybe ad campaigns and everything on Facebook, Instagram, on websites a lot of people frequent.” P11-006: “That’s an only better advertising because I had no idea-- they were so unclear. It was all word of mouth to find one. With all word of mouth, and then you needed to get the link. And it was hard to actually do it.” |

| Meeting Structure | 17.7 | 18 |

P67 (AA 2069): “I think there needs to be more like help, inclusiveness for people that are new … in the end of a meeting put up your email across the screen or something and “hey anyone who just wants help shoot a message to this email. I know it can be timid to talk on-screen so here, private message me,” something like that. You know I mean? There’s nothing like that that I’ve seen to maybe help those people that are too scared to reach out.” P12-009: “I think if they have fewer people. I mean, in some meetings there are like 50 people, and it just becomes …too big …online meetings should be small amount of people to make sure everybody shares. They should have more people involved. Some people we were taking over and it was kind of so-and-so’s and so-an-so’s meeting, you know what I mean? …There’s some of these groups that were holding online meetings ignoring the actual group culture, You know what I mean? Yeah. So from that perspective.” |

| Tech Support | 12.9 | 12 |

P27 (AA 2026): “It took a while for me to figure out how to use the online platform, but if they have like a tutorial, instead of having it like figure it out on your own, if they had some kind of tutorial to help you just navigate the platform” P71 AA 2073: “There are a couple people I know that actually don’t like technology and they don’t have a computer and they’ve had to go and find somebody to do something. …So it seems like technology’s probably a big barrier for some people.” |

| Central Resource | 11.3 | 11 |

P13-058: “Well, I don’t know how this could happen, but it was always hard to find out what meetings were available because it’s not like there was an AA site. You know what I mean? It was always through word of mouth. So some sort of national site that had everything on it would be helpful.” P63 AA 2065: “I think just having somewhere that maybe can catalog or categorize stuff better. That’d be good. …You can search for a location, and needs, and have just everything sort of connected would be great.” |

| Requested Resources | 58.1 | 52 | |

| In-Person Resources | 32.3 | 24 |

P142 (SM 321): “Maybe organize some outdoor meetings or I know for instance, in my town we have a beach and they have picnic tables set up but the picnic tables are under a roofed structure. So I mean, you could probably do some small groups because there’s like 10 or 12 of these picnic tables with cement patios, a picnic table and then a roof over them. You could probably just go there and hold smaller meetings in smaller clusters.” P61 AA 2063: “I mean, in-person stuff …I really like group stuff. And it’s not visible to me the way it would be if I was there and seeing notices for it and talking with people as much.” |

| Additional/Other Meeting Options | 12.9 | 12 |

P77 (AA 2079): “That might’ve been a nice thing to have like a social group of like-minded people to go to on a Friday night if my friend, wasn’t available or something to do that instead.… I’m not exactly sure what kind of supportive group, but I would have had the time to try something like that, yeah… I think that a support group might be nice.” P72 AA 2074: “I mean, I’d rather see a motivational speaker than a meeting but I don’t know if they have something where they just talk to you or whatever about how-- I don’t know.” |

| One-on-One Aspect | 8.1 | 6 |

P119 (SM 182): “Well, I think maybe a personal phone call once a week would help, keep me motivated, give me a chance to get whatever’s on my chest off my chest sometimes, so it doesn’t push me towards the drink.” P4 AA 2002: “So I think one of the biggest-- so to meet my needs specifically, would probably require somebody reaching out to me to try to keep me on track, which would mean, probably, my PCP who gave me a prescription for naltrexone would have checked in on me, seeing how it went. I never took the stuff but he doesn’t know that. And so, if there had been-- I guess it’s too much to ask in today’s world. I understand that. But that’s what would have helped me is to have somebody like, “Hey, dummy. What are you doing?” |

Note: %= percentage of total transcripts that the theme was applied at least once. Frequency = number of times the theme was applied across all transcripts.

The third and final subtheme within the Suggestions and Barriers parent theme was Barriers to Access. This subtheme reflected barriers identified by participants that precluded them, or others, from accessing virtual resources. 54.8% of participants identified at least one barrier to accessing virtual resources. Participants spoke about issues with technology, internet access, and difficulties finding a quiet space in their homes to attend meetings. For example, one participant said:

“I would say having it be in my own home. Do you know what I mean? And not having—I mean I can usually find a quiet spot, but it’s much easier if I’m going out and there’s already an established place where we’re meeting. So just finding a quiet place in my own house-- that’s been the challenge. Technology so far has been okay, but I know for others it’s been challenging”.

(P13-028)

Overall, the themes that emerged within the overarching Recovery Resources theme revealed heterogeneity in participant experiences with virtual resources: while many expressed positive experiences, a substantial number reported negative experiences as well (43.5%). It also revealed that participants had specific ideas on suggested areas for improvement, specific requests for additional resources, and that they identified barriers to accessing resources.

Effect on General Life

The third overarching theme was Effect on General Life, which encompasses parent and subthemes that captured how COVID-19 and the related restrictions have impacted more varied aspects of participant’s lives. While this theme is not proximally related to recovery, it was included to further characterize COVID-19 impacts on the lives of those recovering from an AUD. Two parent themes were included in this overarching theme: Impact on Daily Life and Impact on Relationships and Social Life.

The parent theme Impact on Daily Life was present across all transcripts and spoke to how COVID-19 and the related restrictions impacted participants’ daily lives in varied ways, outlined in the seven subthemes: Adaptive Coping Mechanisms, Routine, Technology Use, Poor Mental Health/Mood, Isolation, Employment, and Negative Experiences with Societal Response to Virus.

Adaptive Coping Mechanisms was present in 100% of transcripts and was applied when participants talked about mechanisms they used to cope with their recovery and the pandemic during the COVID-19 lockdown aside from drinking or substance use. The three most commonly reported coping mechanisms were social interactions (65 applications), mindset and routine (63 applications), and physical activity (63 applications). Some participants spoke about how they would plan their days around their coping activity as something to look forward to, and some would use it as a reason to not drink:

“Yoga, especially, there’s been days--or working out or exercise. There have been days where I don’t decide to have a drink. So I’m like, “No, I want to work out later or do yoga later.” And I know if I have a drink, that won’t happen, or. Yeah. So that’s, definitely, a good coping mechanism”.

(P13–077)

For more information on the reported adaptive coping mechanisms, see Figure 4. The second subtheme, Routine, was present across 98.4% of transcripts. This subtheme spoke to how participants daily routines were disrupted or changed as a result of the COVID-19 restrictions. Some participants talked about how the closing of work, businesses, and schools allowed them to focus on creating healthy habits, while others talked about how everything closing disrupted their lives, and how they had to accommodate to the new virtual life.

“In terms of work and everything, I definitely notice change because it made it so that my workplace was closed. My university was closed. And everything went online, so I accommodated to that as well as everyday life, so not even just being able to go on walks and stuff or outside without having an absolute necessity”.

(P169 SM 446)

Figure 4:

Number of Mentions of The Types of Reported Adaptive Coping Mechanisms

Note: Number of mentions does not add to 290. This is because the parent theme was only applied once per excerpt, even if multiple types of adaptive coping mechanisms were endorsed. MHO = Mutual Help Organization

The third subtheme, Technology Use, was present across 91.9% of transcripts and was applied when participants referenced technology use in their life. Participants often referenced how they have increased their use of technology. They talked about being online more, and some participants cited feeling more connected to friends and family through the use of social media. Others talked about being constantly on a screen with more negative connotations. For example, one participant said: “I’ve been on social media like a crazy person… Because I have nothing better to do” (P11–051).

The fourth subtheme under Impact on Daily Life was Poor Mental Health/Mood. It was present across 85.5% of transcripts. Some participants reflected on how frustrations and difficulties with being stuck at home has impacted their mood more generally, while others expressed explicit concerns that their symptoms of depression or anxiety have increased. One participant stated: “I mean it’s been very stressful, anxiety, depression, my PTSD’s kicked in, my insomnia, it’s just been everything triple from my regular, normal, everyday challenge”. (P133 SM 286)

The fifth subtheme, Isolation, was present across 74.2% of transcripts. It was applied when participants spoke about loneliness and isolation as a result of the COVID-19 lockdown. Some participants talked about how they used virtual resources and technology to combat feelings of isolation, while others talked about frustrations about keeping oneself isolated for long periods of time. One participant stated: “I’ve been extremely Covid-careful. I haven’t had a person in my car since February with me. … I haven’t really seen my friends that much. I kept my bubble very small, and I still do”. (P77 AA 2079)

The sixth subtheme was Employment. This subtheme was present in 56.5% of transcripts. It was applied when participants talked about how their employment was impacted by COVID-19. For those that kept their job, participants expressed stress around managing COVID related stressors, and those that either lost their jobs or were attempting to look for work expressed discouragement and stress related to not having a job and difficulties searching for work. For example, one participant said:

“Before it started, I was in the process of starting employment and that kind of shut that down. I do have a phone interview and stuff and… the whole thing kind of went left and I’m thinking it’s primarily because of the coronavirus. So I have so much time on my hands, it’s just driving me crazy” (P58 AA 2060).The seventh subtheme, Negative Experiences with Societal Response to Virus, was present across 50% of transcripts. This subtheme was applied when participants spoke about negative experiences with how society has responded to the pandemic. Participants reported feeling frustration with those who did not follow COVID-19 regulations, anti-mask protests, and the underlying pressure involved with being out in public. One participant stated:

“When you do go to a store or a place, the lineups, the feeling kind of too much, too many rules. You didn’t feel comfortable and I didn’t like all those little other people’s responses back to you. If you went down the wrong aisle in the grocery store, and if you got close to someone they got all freaked out on you. People weren’t being nice anymore. It was frustrating in that context”.

(P12-009)

The second parent theme within the overarching theme Effect on General Life was Impact on Relationships and Social Life. This parent theme was present in all transcripts and spoke to how participant’s relationships and social lives were impacted by COVID-19 and the related restrictions. It included three subthemes: Friend and Family Substance Use, Negative Impact on Relationships, and Positive Impact on Relationships. The first subtheme, Friend and Family Substance Use, was present across 93.5% of transcripts. It was applied when participants spoke about their friends or family’s substance use during the COVID-19 lockdown. Some participants spoke about increases, decreases, or stability in their friends and family’s substance use more generally, while others specifically talked about how friends also in recovery have relapsed, and how friends have used COVID-19 as a justification to relapse. One participant stated:

“Not my family, that’s for sure. But some of my friends from AA, yeah. Yeah. Very few people that got out of Homewood [treatment centre] when I did, that haven’t picked up a drink. I think, maybe three or four. The rest of us have all relapsed”.

(P13-063)

The second subtheme, Negative Impact on Relationships was present in 82.3% of transcripts. This subtheme was applied when participants spoke about how COVID-19 restrictions impacted their relationships negatively. Some participants talked about how being in close quarters all day every day with family members and significant others has been difficult and stressful, while others reported feeling less connected to friends and family, falling out of touch with friends, difficulties connecting through virtual means, and how relationships suffered in the absence of in-person gatherings. One participant stated:

“I feel like it’s much harder to maintain the friendship and the communication, the physical touch stuff with hugs and with family and with others. Yeah, so and being with others when I-- the few times I am able to be with others, everybody wearing a mask is really odd. And I get a lot of communication from the body language, so that’s a big loss”.

(P108 SM 139)

The third subtheme, Positive Impact on Relationships, was applied when participants spoke of any positive impacts on their relationships or social life due to COVID-19. 56.5% of participants reported positive experiences. Participants spoke about a feeling of togetherness, a greater sense of openness because everyone was going through the same world event, and remarked on the ability to stay in touch with people they normally would not have via virtual means. Further, they reported feeling bonded and having an easier time connecting with those that were also making a recovery attempt through the pandemic, because of the common difficulties. One participant stated:

“It’s brought me and other people closer together. …Just accepting that life is short, and being away from people especially when …it’s not your choice to be away. So I find myself picking up the phone more and just interacting through Zoom or through WhatsApp or a lot of video and stuff and just I feel like I was talking to people more than I normally would because life gets busy”.

(P86 SM 23)

Overall, the themes that are included within the overarching theme Effects on General Life reflects the varied domains in which COVID-19 restrictions have impacted participants lives more broadly, whether that is their mental health, daily routine, employment situation, use of technology, or impacts on their relationships. While the tone of this overarching theme was fairly negative (e.g., reports of isolation, poor mental health and frustrations and stress regarding societal responses), participants also reported silver linings and positivities (e.g., all participants endorsing some use of an adaptive coping mechanism, positive impacts on social lives and relationships).

Additional Analysis: Theme Co-occurrence

Figures 5 and 6 provide more information on parent theme and subtheme co-occurrences. The parent theme co-occurrence analysis found that the parent themes related to one another and often co-occurred. The two most commonly co-occurring pairs of parent themes both included Impact on Daily Life – first with Experiences with Virtual Resources (301 co-occurrences) and then with Impact on Relationships and Social Life (139 co-occurrences). Additionally, Impact on Daily Life was the parent theme that most frequently co-occurred with the most parent themes. This is not surprising, given that this was the most frequently applied parent theme and included the largest number and most diverse set of subthemes.

Figure 5:

Co-occurrence Among All Parent Themes Across Transcripts

Figure 6:

Co-occurrence Among All Subthemes Across Transcripts

Note: The parent themes Negative Effect on Recovery, Changes to Recovery Strategies, and Positive Effect on Recovery were included in this analysis to investigate how effects on recovery related to the diverse subthemes.

The subtheme analysis also included the Effect on Recovery parent themes: Negative Effect on Recovery, Strategy Changes, and Positive Effect on Recovery. They were included to further investigate how effects on recovery co-occurred with the more varied and specific subthemes. This analysis found that the modal co-occurrence was zero - demonstrating that the subthemes were generally independent of each other. However, some subthemes did commonly co-occur. Overall, Technology Use was the subtheme that most frequently co-occurred with the widest range of other subthemes, followed by Routine. The top three subthemes that Technology Use co-occurred with were Positive Experiences with Virtual Resources (116 co-occurrences), Adaptive Coping Mechanisms (74 co-occurrences), and Comparison to In-Person Resources (72 co-occurrences). Routine most commonly co-occurred with Poor Mental Health/Mood (45 co-occurrences), Isolation (39 co-occurrences), and Negative Effect on Recovery and Technology Use (30 co-occurrences each). The subthemes that most frequently co-occurred with Negative Effect on Recovery were Poor Mental Health/Mood (36 co-occurrences), Routine (30 co-occurrences), and Isolation (24 co-occurrences). The subthemes that most frequently co-occurred with Positive Effect on Recovery were Routine (15 co-occurrences), Technology Use (13 co-occurrences), and Positive Experiences with Virtual Resources (13 co-occurrences).

Discussion

The aims of this study were to use qualitative methods to explore, first, how COVID-19 impacted recovery attempts of those with an AUD and, second, participant experiences with virtual recovery resources. Analyses revealed three broad overarching themes: Effect on Recovery, Recovery Resources, and Effect on General Life. Within all three themes were subthemes that reflected remarkable heterogeneity in participant experiences, including both negative and positive impacts due to COVID-19 restrictions. These findings suggested that while participants faced significant hardships, there were also unexpected silver linings and positive effects due to the pandemic. For example, there were subthemes for both positive and negative effects on recovery, positive and negative experiences with virtual resources, and positive and negative impacts on relationships. Adding to this complexity, some participants reported both positive and negative effects from COVID-19 restrictions, highlighting that positive and negative impacts were not mutually exclusive – both could be experienced and recognized by the same person. While one might expect both positive and negative experiences due to the pandemic in a healthy, non-AUD sample, it was unexpected that this sample of recovering AUD participants experienced positive effects across all domains. It was particularly interesting that the overarching Effect on Recovery theme was not ubiquitously negative, with Positive Effect on Recovery emerging as a theme. Given the routine disruptions, isolation, and restrictions on social gatherings caused by COVID, one would have expected that the pandemic would have had a more ubiquitously negative impact on participants recovery than what was actually reported. This finding that participants fared generally better than expected makes sense when one considers research findings that the median number of recovery attempts for those with an AUD is only 2, suggesting that AUD is less chronic than previously thought (Kelly et al., 2019; MacKillop, 2020).

In addition, participants identified areas for improvement to existing recovery resources and provided requests for additional resources. Improvements in Accessibility was the most popular suggestion for improvement (present across the most transcripts and most frequently cited improvement category). Participants reported struggles among their peers who lacked access to technology or the internet, and therefore could not access virtual resources. It is important to note that the participants in this study had access to the phone or internet, so accessibility issues are likely more widespread than suggested by the present sample. The most popular requested resource was In-Person Resources (present across the most transcripts and most frequently cited requested resource). This finding reflected that despite the existence of virtual resources, participants still wanted some form of in-person resource. Together, these findings highlighted that while participants did report positive experiences, a switch to predominantly virtual resources for the long-term may not be preferable for many users.

Finally, the theme co-occurrence analysis revealed the subtheme that most frequently co-occurred with other subthemes was Technology Use, followed by Routine. Both subthemes co-occurred at least once with the majority of subthemes, suggesting that technology use and routine disruptions pervaded the most diverse areas of participant lives during the COVID-19 lockdown. This finding makes sense, given that the COVID-19 pandemic and related restrictions upended routines, and restrictions on in-person gatherings left technology use as the primary method of communication and connection. The co-occurrence analysis also revealed that Negative Effect on Recovery co-occurred with more negatively valenced subthemes, such as Poor Mental Health/Mood, and Isolation. On the other hand, Positive Effect on Recovery most commonly co-occurred with more positively valenced subthemes, such as Positive Experiences with Virtual Resources, and Technology Use. Additionally, it is interesting that Routine also commonly co-occurred with both Negative Effect on Recovery and Positive Effect on Recovery. It may be that routine disruptions were helpful for those that used restrictions as the impetus for a mindset change to focus on recovery, while those that experienced routine disruptions more negatively experienced a negative effect on their recovery.

These findings can be understood within the context of resilience, defined here as “positive adaptation in spite of adversity” (Luthar et al., 2000). Indeed, findings from this study demonstrated that in spite of the major adversity of COVID-19, many individuals who were particularly at-risk for increases in substance use nonetheless found ways to adapt in order to protect their recovery throughout the pandemic. Participants who employed resilience against pandemic impacts often spoke of adapting to lean on virtual recovery resources or utilizing other coping mechanisms such as physical activity or social interactions in order to maintain their recovery. The resilience demonstrated by participants in this study further highlights that those recovering from an AUD can be versatile and flexible in finding ways to engage with their recovery during the pandemic. Findings from this study are consistent with the Process Model of Addiction and Recovery outlined by Harris and colleagues (2011). This model, developed for maladaptive behaviors such as gambling and self-harm, proposes that those who continually utilize healthy coping mechanisms in response to negative emotionality/adversity build relapse resiliency, while those who respond with unhealthy behaviours (e.g., substance use) may experience short term relief, but also long-term negative effects. In this study, participants spoke about leaning on healthy coping mechanisms in response to the stresses of COVID-19 to help them maintain their recovery and solidify healthy behavioural patterns. Those who experienced more negative effects on their recovery spoke about relapsing as a result of the stresses caused or accentuated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, the co-occurrence analysis revealed that Positive Experiences with Virtual Resources was often spoken about with Positive Effect on Recovery, while Poor Mental Health/Mood and Isolation was often spoken about with Negative Effect on Recovery.

A broad implication of this study is the meaningful reminder that participant experiences are not unidimensional and may not be fully represented in forced answer surveys such as Likert or dichotomous scale formats. Participant experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic were multifaceted and dimensional, as represented by the endorsement of positive, negative, and both positive and negative effects due to the pandemic. Future COVID-19 pandemic related research should include probes for positive effects. Without these positive impact probes, researchers will miss a perspective that was endorsed by a sizeable proportion of participants.

This revelation that participants experienced positive effects on their recovery due to the pandemic opens avenues of exploration on the individual differences that predict experiencing positive effects on recovery during a global stressor such as a pandemic. While our study points towards subthemes such as Positive Experiences with Virtual Resources, Technology Use, and Routine as potential indicators, future research should also follow up to develop a more detailed and nuanced understanding. Further, while this study focused on the broader experiences of a heterogenous sample, future work should investigate whether there are nuanced differences in participant experiences based on demographic and recovery related variables such as age, gender, ethnicity, time in recovery, and use status. For example, research has found that abstinence duration is inversely related to risk of relapse, and that stress is associated with higher relapse rates (Sliedrecht et al., 2019). Thus, those earlier in their recovery or those experiencing more stress as a result of the pandemic may be at an increased risk for negative effects on their recovery and may have differing experiences during the pandemic. Additionally, research has demonstrated that younger and older populations use substances for differing reasons: older populations tend to use for coping and enhancement purposes, while younger populations tend to be more socially motivated in their substance use (Gilson et al., 2017; Shank et al., 2020). Future research should investigate how age may result in differing experiences on pandemic impacts. This is important next step to further understand how the pandemic has impacted more specific subgroups that may be more at risk for relapse.

Another implication from this study is that perhaps there may be opportunity for restructuring the way we think about spaces and platforms for treatment provision. It may be possible to adjust our perspectives so that treatment or mutual support settings need not be based on geography and physical spaces. At the same time however, this study found evidence that service providers and program managers should be wary of a complete or large-scale replacement of in-person recovery resources with virtual recovery resources, given our finding that a sizeable proportion of participants had negative experiences with virtual resources, faced barriers to utilization, and that in-person resources were the most frequently requested resource. There remains a need for in-person resources and innovative strategies to aid in maintaining social support and engagement in recovery through the pandemic for those who dislike virtual resources. In other words, the treatment landscape needs to be more multifaceted and able to offer diverse versatile options to highly varying patient preferences. Also, future research should address the both the viability of implementing the suggested improvements that were identified by participants, and more rigorously investigate the effectiveness of virtual resources.

There were limitations to this study. The foremost consideration was the atypical recruitment methods. Participants in this study were recruited from a study which further recruited its participants from two multi-site, longitudinal research studies. Because of these atypical recruitment methods, the sample was extremely heterogenous - participants were located in both Canada and the United States, engaged in formal (i.e., inpatient or outpatient facilities) and informal recovery attempts (i.e., used own methods outside professional services), and varied widely in the number of days spent in recovery. While we are unable to make distilled conclusions about a group of participants, this heterogeneity may also be thought of as a strength insofar as it may capture a broader range of experiences. Considering the exploratory nature of the study, these varying perspectives were informative. A related limitation is that while there may be differences between Canada and the USA, interviews were analyzed together, and as such this study cannot speak to between country differences. A third limitation to this study is lack of racial diversity, as 71% of the sample identified as White/Caucasian. Thus, the results of this study may not adequately represent the experiences of racial minorities. However, the study did have a low overall median income of 15–30 thousand dollars USD/CAD, capturing the experiences of those coming from lower income households, which historically tend to not be represented. Additionally, a buffering strength of this study was its particularly large sample size for a qualitative study (N = 62).

Conclusion

Recognizing these limitations, the current study elucidated perspectives and insights on the experiences of those making a recovery attempt from an AUD during the COVID-19 pandemic, and provides a window into how those recovering from an AUD responded to the pandemic at its most uncertain point. Collectively, findings suggest that participants varied greatly within themselves and between others in how COVID-19 restrictions impacted their recovery, their experiences with virtual resources, and their lives more broadly. This study provides evidence that participants experienced not only significant hardship, but also unexpected silver linings that have resulted in positive impacts on participants recoveries. Additionally, the finding that a substantial number of participants reported negative experiences with virtual resources, and suggestions for improvements signals that there is room to grow and adapt virtual resources to better suit the needs of those that use them.

Supplementary Material

Public Significance Statement:

This study found heterogenous impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on those recovering from an alcohol use disorder, with some reporting negative effects, some reporting positive effects, and some reporting both positive and negative effects. Additionally, areas for improvement in existing virtual resources were identified.

Acknowledgements and Disclosures

This study was supported by grants R01AA025849, R01 AA026288, and K24 AA022136 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and the Peter Boris Chair in Addictions Research. The funding source had no other involvement other than financial support. All authors named have significantly contributed to the authorship of this article and have read and approved the final manuscript. James MacKillop is a principal in BEAM Diagnostics, Inc. and consultant to Clairvoyant Therapeutics; no other authors have potential conflicts of interest to disclose. No material in this manuscript has been presented or reported elsewhere. The authors are grateful to the research staff who contributed to data collection, and to the participants for their time and effort. A prior pre-print version of this article may be viewed at: 10.31234/osf.io/8dk7h

References

- Alpers SE, Skogen JC, Mæland S, Pallesen S, Rabben ÅK, Lunde L & Fadnes LT (2021). Alcohol consumption during a pandemic lockdown period and change in alcohol consumption related to worries and pandemic measures. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3). doi: 10.3390/ijerph18031220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashford RD, Brown A, Canode B, Sledd A, Potter JS & Bergman BG (2021). Peer based recovery support services delivered at recovery community organizations: Predictors of improvements in individual recovery capital. Addictive Behaviours, 119 doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman BG & Kelly JF (2021). Online digital recovery support services: An overview of the science and their potential to help individuals with substance use disorder during COVID-19 and beyond. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 120. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman BG, Kelly JF, Fava M & Evins EA (2021). Online recovery support meetings can help mitigate the public health consequences of COVID-19 for individuals with substance use disorder. Addictive Behaviours, 113. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callinan S, Smit K, Mojica-Perez Y, D’Aquino S, Moore D & Kuntsche E (2020). Shifts in alcohol consumption during the COVID‐19 pandemic: early indications from Australia. Addiction, 116, 1381–1388. doi: 10.1111/add.15275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell W, Hester RK, Lenberg KL & Delaney HD (2016). Overcoming Addictions, a web-based application, and SMART Recovery, an online and in-person mutual help group for problem drinkers, Part 2: Six-month outcomes of a randomized controlled trial and qualitative feedback from participants. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(10). doi: 10.2196/jmir.5508: 10.2196/jmir.5508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2020). Implementation of mitigation strategies for communities with local COVID-19 transmission. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/downloads/community-mitigationstrategy.pdf.

- Cope M (2016). Organizing and analyzing qualitative data. In I. H, Qualitative research methods in human geography (4th ed) pp. 279–294. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- DeJong CAJ, Verhagen JGD, Pols R, Verbrugge CAG, & Baldacchino A (2020). Psychological impact of the acute COVID-19 period on patients with substance use disorders: We are all in this together. Basic and Clinical Neuroscience, 11(2), 207–216. 10.32598/bcn.11.covid19.2543.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elison S, Jones A, Ward J, Davies G & Dugdale S (2017). Examining effectiveness of tailorable computer-assisted therapy programmes for substance misuse: Programme usage and clinical outcomes data from Breaking Free Online. Addictive Behaviors, 74, 140 – 147. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KS, Smock SA, & Wilkes MT (2011). Relapse resilience: A process model of addiction and recovery. Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 22(3), 265–274. 10.1080/08975353.2011.602622 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jemberie WB, Stewart Williams J, Eriksson M, Grönlund AS, Ng N, Blom Nilsson M, Padyab M, Priest KC, Sandlund M, Snellman F, McCarty D, & Lundgren LM (2020). Substance use disorders and COVID-19: Multi-Faceted problems which require multi-pronged solutions. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 1–9. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Hoeppner B, Stout RL & Pagano M (2012). Determining the relative importance of the mechanisms of behavior change within Alcoholics Anonymous: a multiple mediator analysis. Addiction, 107, 289–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03593.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Greene MC, Bergman BG, White WL, & Hoeppner BB (2019). How many recovery attempts does it take to successfully resolve an alcohol or drug problem? Estimates and correlates from a national study of recovering U.S. adults. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 43(7), 1533–1544. 10.1111/acer.14067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilian C, Rehm J, Allebeck P, Braddick F, Gual A, Barták M, Bloomfield K, Gil A, Neufeld M, O’Donnell A, Petruželka B, Rogalewicz V, Schulte B, Manthey J (in press). Alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe: a large-scale cross-sectional study in 21 countries. Addiction. doi: 10.1111/add.15530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krentzman AR (2021). Helping clients engage with remote mutual aid for addiction recovery during COVID-19 and beyond. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 39(3), 348–365. doi: 10.1080/07347324.2021.1917324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, & Becker B (2000). The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71(3), 543–562. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1885202/pdf/nihms-21559.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]