Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Severe inflammation and oxidative stress seen in COVID-19 patients cause cumulative antiviral effects, and serious inflammation increases tissue, oxidative damage, and DNA damage. Therefore, in this study, oxidative stress, DNA damage, and inflammation biomarkers were investigated in patients diagnosed with COVID-19.

METHODS

In this study, blood samples were obtained from 150 Covid-19 patients diagnosed by polymerase chain reaction and 150 healthy volunteers with the same demographic characteristics. Total oxidant status (TOS), total antioxidant status (TAS), total thiol (TT), native thiol, and myeloperoxidase (MPO) activities were measured by photometric methods. The levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β), and interleukin 6 (IL-6), which are inflammation markers, were measured by the ELISA method using commercial kits. The genotoxic effect was evaluated by Comet Assay.

RESULTS

The oxidative stress biomarkers; Disulfide, TOS, MPO, oxidative stress index, and IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α levels of inflammation biomarkers and the DNA damage in COVID-19 patients were increased (p<0.001), and the levels of TAS, TT, and NT In COVID-19 patients were decreased (p<0.001).

CONCLUSION

In COVID-19 patients, induced DNA damage, inflammation, and oxidative stress can guide the prognosis and treatment strategies of the disease.

Keywords: COVID-19, genotoxicity, oxidative stress

Highlight key points

Severe inflammation and oxidative stress seen in patients cumulatively cause an antiviral effect, as well as an extreme increase in tissue inflammation, oxidative damage, and DNA damage.

Total thiol and native thiol values were statistically significantly lower in COVID-19 patients, and disulfide values were significantly higher.

While oxidative stress and inflammation are induced in COVID-19 patients, antioxidant defenses decrease.

Increased inflammatory markers IL1β, IL6, and TNFα are associated with COVID-19 disease severity.

Coronaviruses (CoV) are single-stranded, positive polarity enveloped RNA viruses that cause a variety of illnesses as middle eastern respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV). New mutated version of the virus has been accepted as SARS-CoV-2. The virus is in the Sarbecovirus subgenus within the beta coronavirus genus, including SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, and was named COVID-19 by the World Health Organization [1]. The mechanism of infection is that the virus binds to Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2). This complex is taken up and replicated by the host cell [2]. The onset of symptoms (incubation period) from exposure to COVID-19 is 2–14 days. Many people with confirmed COVID-19 infection cause severe acute respiratory disease with fever, cough, and shortness of breath [3]. The virus is mortal in the elderly and people with chronic diseases namely hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes, with a mortality rate of about 3%. Severe cases are hospitalized and receive “supportive treatment.” The organ in which the COVID-19 virus is most effective is the lungs. The virus travels through the airways to the lungs, binds to the receptors of ACE2 on the cell surface of the alveoli. After this, the virus enters the cell, multiplies inside, and damages the cells [2, 4]. Acute inflammation that caused by the virus is a severe syndrome of acute respiratory failure syndrome, which can be fatal.

Although it has been a year since the virus appeared in the World, the long-term effects of the virus are still a matter of curiosity. Severe inflammation and oxidative stress seen in patients cumulatively cause an antiviral effect, as well as an extreme increase in tissue inflammation, oxidative damage, and DNA damage [5, 6]. In this study, oxidative stress, DNA damage, and inflammation biomarkers were investigated in patients diagnosed with COVID-19.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Study Design

The study was performed between April and June. One hundred and fifty patients (120 men + 30 women) who were applied and diagnosed by polymerase chain reaction for COVID-19 at the Emergency Medicine Department of X. After 150 patients signed, the informed consent form and routinely requested blood samples were studied, the remaining inert blood was investigated. The healthy people with the same demographic characteristics without any chronic diseases were included as the control group. Our article has been prepared in conformity with the Declaration of Helsinki. The ethics were approved by University of Health Sciences Turkiye, Hamidiye Scientific Research Ethics Committee with decision number 21–267.

Blood Sample Collection

Approximately 3 mL of blood from the patients was taken into sterile blood tubes with EDTA. A volume of 200–400 µL was drawn and transferred to 1.5 mL centrifuge tubes from this blood. The residual EDTA blood was 10 min centrifuged at 3000xg. After centrifugation, its plasma was stored at -80°C until analysis.

Alkaline Single Cell Gel Electrophoresis

Leukocyte DNA damage was analyzed by alkaline single-cell gel electrophoresis, namely, the Comet Assay method [7]. For this purpose, 6 µL of whole blood from the thawed whole blood was mixed with low melting temperature agarose (0.7%), then embedded on slides covered with agarose gel (1%) with a normal melting temperature. The coverslip covered and permitted to solidify in a cold environment. After the gel solidified, the coverslips were removed from the slide, and cells were lysed in a lysis buffer for at least 4 h. Subsequently, they were electrophoresed (300 mA) for 20 min in an alkaline buffer (pH 13). The cells stained with Ethidium Bromide (5 mg/mL) were examined by fluorescence microscopy (Excitation DB: 546 nm, Emission DB: 20 nm) after electrophoresis. Tail density (tail %) in DNA was analyzed as a DNA damage signal. Comet analyzes were performed using Comet Assay analysis program IV (Perceptive Instruments, Suffolk, UK), counting an average of 50 cells.

Total Antioxidant Status (TAS) and Total Oxidant Status (TOS) Measurement

The total antioxidant levels of the plasma samples were studied using the method developed by Erel [8]. The test is based on the degradation of the blue-green color formed by ABTS (2,2’-azinobis-3-ethylebenzothiazoline-6-sulfonate) radical with antioxidants in the sample. ABTS is incubated with a peroxidase containing myoglobin (HX-Fe+) and H2O2 to form the ABTS+ radical. The resultant ferryl myoglobin reacts with ABTS to form the ABTS+ radical, it is blue-green in color. This formed color is inhibited according to the ratio of antioxidants in a sample and measured with a Varioskan Multimode Reader (Thermo Scientific, USA) at 600 nm. Ascorbic acid was used as a standard in the calculation of TAS.

The plasma total oxidant levels were determined using the method developed by Erel [9]. The total oxidant test is depending on the oxidation of ferric ion to ferrous ion in the availability of diverse oxidant species. To make it ironic, the oxidants oxidize the iron-a-dianisidine complex. The produced ferric ion makes a colored complex of xylenol orange-ferric ion. In a sample, the amount of oxidant will be associated with the intensity of color. This color-changing was measured with a Varioskan Multimode Reader at a wavelength of 530 nm. As a standard for TOS calculation, H2O2 was used. The oxidative stress index (OSI) was calculated as TOS/TAS.

Thiol-disulfide (DIS) Homeostasis

The “Modified Ellman method” of Erel and Neselioglu was used for total and free thiol measurement [10]. For total thiol (TT) measurement, 10 µL of R1 (reagent 1), and for free thiol measurement, 10 µL of R1’ was added to 10 µL sample. Then, by adding R2 and R3, the first absorbance (A1) reading was done spectrophotometrically at 415 nm wavelength a Multimode Reader. The second absorbance (A2) reading occurred at the same wavelength in the 10th min when the reaction plateaued. The measurement was completed by obtaining the A2-A1 absorbance difference. In calculating total and free thiol levels, 5-thio-2-nitrobenzoic acid, 14.100 mol/L-1cm-1 was used. The DIS level was calculated as µmol/L using the below formula:

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) Enzyme Activity Measurement

The plasma MPO enzyme activity of the samples was determined by the modified o-dianisidin-H2O2 method for 96-well plates. Plasma samples (20 µL) were added to 0.53 mmol/L o-dianisidin dihydrochloride and 50 mmol/L of potassium phosphate buffer with pH 6.0. Then incubated for 10 min at room temperature. After incubation, the change in absorbance (ε= 10062/M/cm) was measured. Results are expressed in U/L for 10 min.

Inflammation Markers

The levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) (BT Laboratory E0082Hu), IL1β (BT Laboratory E0143Hu), and IL6 (BT Laboratory E0090Hu) were measured by commercially purchased ELISA kits by the photometric method.

Statistical Analysis

Parametric data were expressed as mean±standard deviation, while non-parametric data as the interquartile range (IQR). Shapiro–Wilk test was used for normality distribution. The difference between the two parameters was calculated using the Mann–Whitney U test. To compare more than two independent parameters, Kruskal–Wallis test was used. Using the Spearman rank correlation coefficient, the correlation between two variables was evaluated. The chi-square test was used to evaluate the categorical data. Moreover, the p<0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed by the SPSS version 25.0 program (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

Considering the demographic characteristics of the study groups, no significant difference was observed between the patient and control group in terms of gender (20W;130M) and mean age (35.60±10.10; 34.31±9.35).

Oxidative Stress Biomarkers

The DIS, TOS, MPO, and OSI in which oxidative stress was indicated oxidative damage were significantly increased in the COVID-19 patients than the healthy control group (p<0.001). TAS, TT, and NT levels, which indicate antioxidant capacity, were statistically significantly decreased in COVID-19 patients (p<0.001), see Table 1.

Table 1.

Oxidative stress biomarkers in COVID-19 patients and healthy controls

| Oxidative stress biomarkers | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy control, Mean±SD | COVID-19, Mean±SD | ||

| TOS µM H2O2 Eq./L | 9.61±2.94 | 15.10±2.76 | 0.001 |

| TAS µM Ascorbic acid Eq./L | 1.12±0.19 | 0.73±0.15 | 0.001 |

| OSI AU | 9.14±3.96 | 22.16±8.89 | 0.001 |

| MPO U/L | 54.56±16.01 | 140.63±21.70 | 0.001 |

| TT µmol/L | 560.43±60.07 | 475.50±63.39 | 0.001 |

| NT µmol/L | 457.52±84.97 | 312.07±62.05 | 0.001 |

| DIS µmol/L | 51.45±33.70 | 81.72±28.19 | 0.001 |

SD: Standard deviation; TOS: Total oxidant status; TAS: Total antioxidant status; OSI: Oxidative stress index; MPO: Myeloperoxidase; TT: Total thiol; NT: Native thiol; DIS: Disulfide.

Inflammation Biomarkers

The levels of inflammation biomarkers TNF-α, interleukin 1 beta, and interleukin 6 (IL-6) were shown in COVID-19 patients. As seen in Table 2, the data increased statistically significantly compared to the healthy control group (p<0.001).

Table 2.

Inflammatory biomarkers in COVID-19 patients and healthy controls

| Inflammatory biomarkers | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy control Mean±SD | COVID-19 Mean±SD | ||

| IL-1β pg/L | 103.35±18.24 | 363.30±124.36 | 0.001 |

| IL-6 ng/L | 64.85±36.25 | 326.08±84.47 | 0.001 |

| TNF-α ng/L | 81.70±37.04 | 219.43±49.90 | 0.001 |

SD: Standard deviation; IL-1β: Interleukin 1βeta; IL-6: Interleukin 6, TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor α.

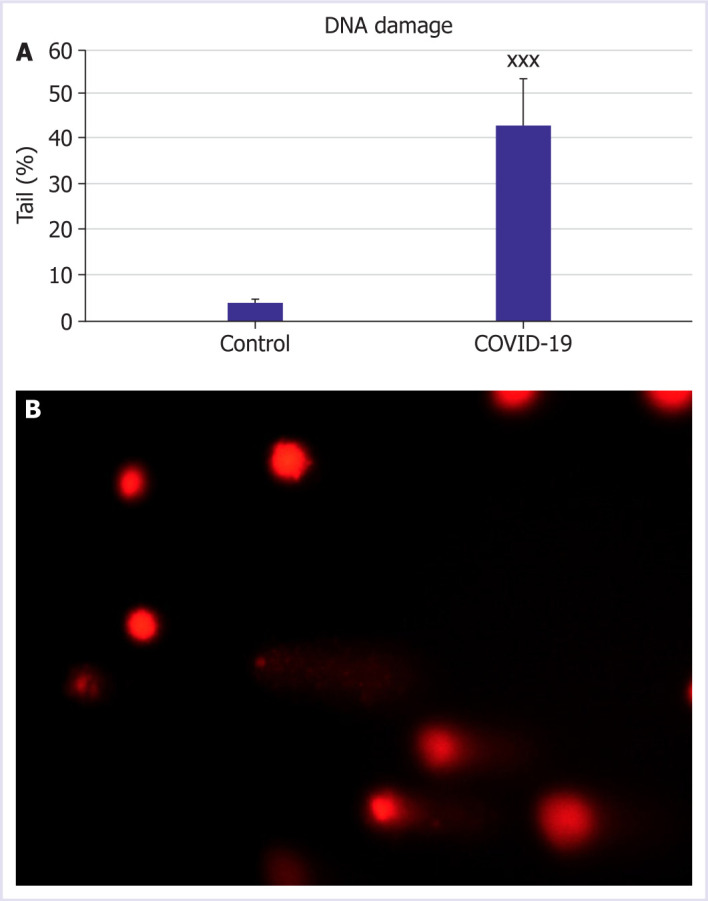

Comet Assay

To evaluate DNA damage in patients diagnosed with COVID-19, comet assay method was used. The amount of damage is given as % tail density. The mean tail percentage for COVID-19 patients was 43.10±10.17, and for the control group was 4.04±0.82. In COVID-19 patients, DNA damage increased statistically according to the healthy control group (p<0.001), Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Effect of COVID-19 patients on DNA damage. (A) Percentage DNA in tail determines in COVID-19 patients and control group. (B) Representative image of DNA damage pattern in COVID-19 patient number 34. Statistically significant differences of relative values in COVID-19 patients xp<0.05, xxp<0.01, and xxxp<0.001 was compared to control. Data are indicated as the mean±standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

In this study, oxidative stress, DNA damage, and inflammation biomarkers were investigated in patients diagnosed with COVID-19. Oxidative stress occurs due to disturbances in the stabilize of production and destruction of ROS. It is characterized by overcoming and damaging the repair capacities of cells through the oxidation of DNA, membrane lipids, and structural proteins [11]. High ROS levels due to respiratory viral infections are related with cytokine production, cellular damage, and oxidative stress or redox imbalance. Virus infection produces large amounts of free radicals, and high ROS levels with these depletion antioxidant mechanisms are crucial for virus replication [12, 13]. Current studies state that oxidative stress is a crucial factor increasing the severity of COVID-19 in patients with lung dysfunction and the cytokine storm from SARS-CoV-2 infection [5, 14, 15]. According to obtained data of our study, OSI levels were significantly increased in COVID-19 patients. These results were confirmed with the literature.

MPO is a crucial enzyme secreted mainly by activated neutrophils and is characterized by pro-inflammatory attributes. The property of COVID-19 is that infiltrating neutrophils release MPO, which activates several pathways leading to cytokine regulation and the production of ROS [16]. A study by Guéant et al. [17] observed elevated MPO-DNA blood levels in positive patients, indicating that this is a sensitive marker of the early stage of COVID-19. Our results demonstrated that the MPO levels increased in COVID-19. These results are consistent with the literature.

Thiols undergo oxidation reactions through oxidizing agents and forms DIS bonds, which can be reduced back to thiol groups, thereby maintaining thiol-DIS homeostasis [18, 19]. In this homeostasis, thiol plays a crucial role in the protection of antioxidants, protein synthesis, cellular growth and proliferation, apoptosis, and cellular signaling mechanism [20]. The previous studies have demonstrated that viral glycoprotein entry is affected by the thiol-DIS balance on the cell surface [21, 22]. According to the data, we obtained in our study, TT and NT values were statistically significantly lower in COVID-19 patients, while DIS values were significantly higher.

Cytokine storm is the extensive and uncontrolled release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and usually occurs as systemic inflammation and multi-organ failure [23]. The levels of IL-2, IL-7, IL-10, TNF-α, and MCP-1 were observed to be higher in severe COVID-19 patients followed in the intensive care unit compared to other patients [5, 24, 25]. In a study by Chen et al. [26], they characterized and compared the immunological features of COVID-19 cases with several disease severity. As a result, they reported that IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-α levels were increased when the serum levels of patients with a severe disease course were compared with moderate severity patients. In our results, IL1β, IL6, and TNFα levels of inflammation biomarkers were statistically significantly increased in COVID-19 patients. In light of all these findings, increased inflammatory markers are related to COVID-19 disease severity.

The comet assay is a method to evaluate DNA damage. This study demonstrated that it induces DNA damage in COVID-19 patients and observed that it is more susceptible to damage than healthy controls. Studies are showing that increased intracellular ROS in viral infection triggers DNA damage [27]. In a study by Singh et al. [28], mitochondrial disruption in SARS-CoV-2 infected lung cell lines were proven to increase inflammation and severity in COVID-19-related sepsis. The only limitation of our study was that the relationship between the radiological prevalence of errors and biomarkers could not be examined.

Conclusion

Our study concluded that while antioxidant defenses decrease in COVID-19 patients, oxidative stress and inflammation are induced. Therefore, induced oxidative stress, inflammation, and DNA damage in COVID-19 patients can guide the prognosis and treatment strategies of the disease. The effects of this increased oxidative stress and inflammation-induced DNA damage in patients diagnosed with COVID-19 should be followed for a long time.

Footnotes

Cite this article as: Bektemur G, Bozali K, Colak S, Aktas S, Eray Metin Guler. Oxidative stress, DNA damage, and inflammation in COVID-19 patients. North Clin Istanb 2023;10(3):335–340.

Ethics Committee Approval

The University of Health Sciences Turkiye, Hamidiye Faculty of Medicine Scientific Research Research Ethics Committee granted approval for this study (date: 02.04.2021, number: 21–267).

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest was declared by the authors.

Financial Disclosure

The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

Authorship Contributions

Concept – GB; Design – GB, SC; Supervision – GB, EMG; Fundings – EMG; Materials – EMG, SA; Data collection and/or processing – EMG, SA; Analysis and/or interpretation – EMG, SA, KB; Literature review – GB, SC; Writing – EMG, KB; Critical review – GB, SC, EMG.

References

- 1.Lov DK, Alkhovsky SV. Source of the COVID-19 pandemic: ecology and genetics of coronaviruses (Betacoronavirus: Coronaviridae) SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 (subgenus Sarbecovirus), and MERS-CoV (subgenus Merbecovirus) Vopr Virusol. 2020;65:62–70. doi: 10.36233/0507-4088-2020-65-2-62-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schönrich G, Raftery MJ, Samstag Y. Devilishly radical NETwork in COVID-19: oxidative stress, neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), and T cell suppression. Adv Biol Regul. 2020;77:100741. doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2020.100741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iddir M, Brito A, Dingeo G, Campo SSFD, Samouda H, Frano MRL, et al. Strengthening the immune system and reducing inflammation and oxidative stress through diet and nutrition: considerations during the COVID-19 crisis. Nutrients. 2020;12:1562. doi: 10.3390/nu12061562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ntyonga-Pono MP. COVID-19 infection and oxidative stress: an under-explored approach for prevention and treatment? Pan Afr Med J. 2020;35(Suppl 2):12. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2020.35.2.22877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beltrán-García J, Osca-Verdegal R, Pallardó FV, Ferreres J, Rodriguez M, Mulet S, et al. Oxidative stress and inflammation in COVID-19-associated sepsis: the potential role of antioxidant therapy in avoiding disease progression. Antioxidants. 2020;9:936. doi: 10.3390/antiox9100936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laforge M, Elbim C, Frère C, Hémadi M, Massaad C, Nuss P, et al. Tissue damage from neutrophil-induced oxidative stress in COVID-19. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;9:515–6. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0407-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh N, McCoy M, Tice R, Schneider E. A simple technique for quantitation of low levels of DNA damage in individual cells. Exp Cell Res. 1988;175:184–91. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(88)90265-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erel O. A novel automated direct measurement method for total antioxidant capacity using a new generation, more stable ABTS radical cation. Clin Biochem. 2004;37:277–85. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2003.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erel O. New automated colorimetric method for measuring total oxidant status. Clin Biochem. 2005;38:1103–11. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erel O, Neselioglu S. A novel and automated assay for thiol/disulphide homeostasis. Clin Biochem. 2014;47:326–32. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2014.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khomich OA, Kochetkov SN, Bartosch B, Ivanov AV. Redox biology of respiratory viral infections. Viruses. 2018;10:392. doi: 10.3390/v10080392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akaike T, Suga M, Maeda H. Free radicals in viral pathogenesis: molecular mechanisms involving superoxide and NO. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1998;217:64–73. doi: 10.3181/00379727-217-44206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan SMH, Selemidis S, Bozinovski S, Vlahos R. Pathobiological mechanisms underlying metabolic syndrome (MetS) in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): clinical significance and therapeutic strategies. Pharmacol Ther. 2019;198:160–88. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Derouiche S. Oxidative stress associated with SARS-Cov-2 (COVID-19) increases the severity of the lung disease-a systematic review. J Infect Dis Epidemiol. 2020;6:121. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang D, Comish P, Kang R. The hallmarks of COVID-19 disease. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16:e1008536. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guéant J, Fromonot J, Guéant-Rodriguez R, Lacolley P, Guieu R, Regnault V. Blood myeloperoxidase-DNA, a biomarker of early response to SARS-CoV-2 infection? Allergy. 2020;76:892–6. doi: 10.1111/all.14533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cremers CM, Jakob U. Oxidant sensing by reversible disulfide bond formation. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:26489–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R113.462929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones DP, Liang Y. Measuring the poise of thiol/disulfide couples in vivo. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:1329–38. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sen CK, Packer L. Thiol homeostasis and supplements in physical exercise. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:653S–69. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.2.653S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yi MC, Khosla C. Thiol-disulfide exchange reactions in the mammalian extracellular environment. Annu Rev Chem Biomol Eng. 2016;7:197–222. doi: 10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-080615-033553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mathys L, Balzarini J. The role of cellular oxidoreductases in viral entry and virus infection-associated oxidative stress: potential therapeutic applications. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2016;20:123–43. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2015.1068760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang W, Zhao Y, Zhang F, Wang Q, Li T, Liu Z, et al. The use of anti-inflammatory drugs in the treatment of people with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): the perspectives of clinical immunologists from China. Clin Immunol. 2020;214:108393. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, Jiang L, Song J. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:846–8. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen G, Wu D, Guo W, Cao Y, Huang D, Wang H, et al. Clinical and immunological features of severe and moderate coronavirus disease 2019. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:2620–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI137244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nadhan R, Patra D, Krishnan N, Rajan A, Gopala S, Ravi D, et al. Perspectives on mechanistic implications of ROS inducers for targeting viral infections. Eur J Pharmacol. 2020;890:173621. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh K, Chen YC, Hassanzadeh S, Han K, Judy JT, Seifuddin F, et al. Network analysis and transcriptome profiling identify autophagic and mitochondrial dysfunctions in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Front Genet. 2020;16:599261. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.599261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]