Abstract

Objectives

With increasing evidence for the clinical utility of pharmacogenomic (PGx) testing for depression, there is a growing need to consider issues related to the clinical implementation of this testing. The perspectives of key stakeholders (both people with lived experience [PWLE] and providers) are critical, but not frequently explored. The purpose of this study was to understand how PWLE and healthcare providers/policy experts (P/HCPs) perceive PGx testing for depression, to inform the consideration of clinical implementation within the healthcare system in British Columbia (BC), Canada.

Methods

We recruited two cohorts of participants to complete individual 1-h, semi-structured interviews: (a) PWLE, recruited from patient and research engagement networks and organizations and (b) P/HCPs, recruited via targeted invitation. Interviews were audiotaped, transcribed verbatim, de-identified, and analysed using interpretive description.

Results

Seventeen interviews were completed with PWLE (7 with experience of PGx testing for depression; 10 without); 15 interviews were completed with P/HCPs (family physicians, psychiatrists, nurses, pharmacists, genetic counsellors, medical geneticists, lab technologists, program directors, and insurers). Visual models of PWLE's and P/HCP's perceptions of and attitudes towards PGx testing were developed separately, but both were heavily influenced by participants’ prior professional and/or personal experiences with depression and/or PGx testing. Both groups expressed a need for evidence and numerous considerations for the implementation of PGx testing in BC, including the requirement for conclusive economic analyses, patient and provider education, technological and clinical support, local testing facilities, and measures to ensure equitable access to testing.

Conclusions

While hopeful about the potential for therapeutic benefit from PGx testing, PWLE and P/HCPs see the need for robust evidence of utility, and BC-wide infrastructure and policies to ensure equitable and effective access to PGx testing. Further research into the accessibility, effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness of various implementation strategies is needed to inform PGx testing use in BC.

Keywords: pharmacogenomics, depression, patient preferences, provider preferences, qualitative research, implementation, pharmacogenetics

Résumé

Objectifs

Avec l’accumulation des données probantes sur l’utilité clinique des tests pharmacogénomiques (PGx) pour la dépression, il y a un besoin croissant d’examiner les questions liées à la mise en œuvre clinique de ces tests. Les perspectives des principaux intervenants (tant les personnes ayant une expérience vécue [PAEV] que les prestataires) sont essentielles, mais pas souvent explorées. La présente étude visait à comprendre comment les PAEV et les prestataires de soins de santé/experts en politique (PSSEP) perçoivent les tests PGx pour la dépression, pour informer l’éventualité d’une mise en œuvre clinique au sein du système de santé de la Colombie-Britannique (C.-B.), Canada.

Méthodes

Nous avons recruté deux cohortes de participants pour mener les entrevues individuelles, d’une heure, semi-structurées : 1) PAEV, recrutées chez des réseaux et des organisations d’engagement de patients et de recherche, et 2) PSSEP, recrutés sur invitation ciblée. Les entrevues étaient enregistrées sur bande audio, transcrites textuellement, dépersonnalisées, et analysées à l’aide d’une description interprétative.

Résultats

Dix-sept entrevues ont été menées avec des PAEV (7 ayant l’expérience des tests PGx pour la dépression; 10 sans); quinze entrevues ont été menées avec des PSSEP (médecins de famille, spsychiatres, infirmières, pharmaciens, conseillers en génétique, généticiens médicaux, technologistes de laboratoire, directeurs de programme et assureurs). Les modèles visuels des perceptions et attitudes des PAEV et des PSSEP à l’égard des tests PGx ont été développés séparément, mais les deux étaient profondément influencés par les expériences antérieures professionnelles et personnelles des participants avec la dépression et/ou les tests PGx. Les deux groupes ont exprimé le besoin de données probantes et de nombreuses considérations pour la mise en œuvre des tests PGx en C.-B., notamment l’exigence d’analyses économiques concluantes, l’éducation des patients et des prestataires, le soutien technologique et clinique, des installations locales pour les tests, et des mesures en vue d’assurer un accès équitable aux tests.

Conclusions

Bien qu’optimistes quant au potentiel d’avantages thérapeutiques des tests PGx, les PAEV et les PSSEP voient le besoin de données probantes robustes de l’utilité, et d’une vaste infrastructure à l’échelle de la C.-B., et des politiques pour assurer un accès équitable et efficace aux tests PGx. Il faut plus de recherche nécessaire sur l’accessibilité, l’efficacité et la rentabilité de diverses stratégies de mise en œuvre pour éclairer l’utilisation des tests PGx en C.-B.

Introduction

For people with depression and their healthcare providers, the process of finding a medication that works in relieving symptoms, while minimizing adverse drug reactions, can be a difficult process of trial-and-error.1,2 This may contribute to medication nonconcordance and, subsequently, to poorer health and long-term prognosis 3 and increased costs to the healthcare system.3,4 Pharmacogenomic (PGx) testing is therefore of great relevance in psychiatry, as it aims to use genetic information (about variations that influence the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of a medication) to aid in finding an antidepressant that works best for each individual patient. PGx tests typically assess multiple genomic variants across multiple genes (“combinatorial PGx testing”) in order to predict gene–drug interactions that can be used to adjust medication choice or dosage.

People with a history of depression have expressed interest in PGx testing, 5 and in Canada, patients who wish/are able to self-pay for PGx tests can access them independently, 6 or with the help of an ordering clinician. There are, however, barriers to the clinical implementation of PGx testing,7,8 and it is not yet clinically routine 9 or – to our knowledge – funded in the vast majority of publicly funded healthcare systems, largely due to the current lack of robust evidence for cost-effectiveness. 10 Evidence for the clinical utility of PGx testing for depression is accumulating,2,7,11–14 including preliminary evidence for improved response and remission rates with PGx-guided antidepressant treatment compared to treatment-as-usual.11–13 And, as evidence for the clinical utility and cost-effectiveness of PGx testing accumulates, it is critical that stakeholders’ interests and concerns – including those of clinicians, administrators, and patients – are also explored and considered in the adoption of PGx testing 15 to help ensure its acceptability and effectiveness within the healthcare system.

Perspectives of people with lived experience (PWLE) and healthcare providers may differ in important ways, and so both are important to explore. With regard to providers’ perspectives, studies to date on PGx testing in psychiatry have largely been based on quantitative survey-based studies and are not specific to depression.16–19 We are aware of only two qualitative studies about PGx for depression specifically.20,21 These data indicate general optimism for the future use of PGx testing and highlight a need for educational and logistical support for prescribing providers, but broader, more conceptual issues related to the implementation of PGx testing in a psychiatric context were lacking.

With regard to the perspectives of PWLE on PGx testing for depression, there have been several qualitative studies exploring why people got testing and their reactions to results, 22 and attitudes towards PGx testing for depression23–25 (among other indications24,25). These studies describe both hopes and concerns for PGx testing. Again, there is little published research concerning perspectives of PWLE on broader, more conceptual issues related to the implementation of PGx testing in a psychiatric context.

Furthermore, no qualitative studies of either PWLE or provider views about PGx testing have been conducted in a Canadian setting. Thus, the particularities of providing PGx testing within the context of the Canadian public healthcare system have not been explored. In order to ensure the effective, equitable, and meaningful provision of PGx testing, we sought to address these gaps. We specifically aimed to explore the perceptions of PGx testing among PWLE and healthcare providers/other professional stakeholders, to inform the process of considering the clinical implementation of PGx testing for depression within the healthcare system in British Columbia (BC), Canada.

Methods

Procedures

As a part of a large, multi-faceted study evaluating the potential effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of introducing PGx testing for depression in BC as a routine part of clinical practice, we conducted a qualitative (interpretive description) semi-structured interview-based study with two groups of stakeholders: (a) PWLE and (b) professional stakeholders (P/HCPs; healthcare providers, policy makers, health insurers, laboratory experts). The Research Ethics Board at the University of British Columbia approved this study (H20-01648).

Data Collection

A semi-structured interview guide was developed for each group with the input of authors CS, EM, LE, AMH, GL, LR, LR, and JA based on their experience with genetics/genetic counselling, PGx research, qualitative research, and/or lived experience with depression (see supplemental information).

Participants for the PWLE group were recruited using a combination of convenience and purposive approaches. Specifically, study advertisements were shared via social media and amplified by mental health networks in BC. A study page was also created on REACH BC (www.reachbc.ca), a provincial initiative connecting BC residents to health researchers. As data collection progressed, in order to target recruitment of people representing groups whom we had not yet captured, we (a) connected with a local men's mental health group who shared our study advertisement with their members/social media followers and (b) connected with the authors of the IMPACT study, 26 who shared our study information with their research participants who had formerly received PGx testing for depression. Interested individuals contacted the study team, were screened for eligibility (i.e., were a resident of BC, fluent in English, and had a self-reported history of depression and antidepressant use), and provided written informed consent prior to the study interview.

For interviews with P/HCPs, targeted recruitment was used to ensure a range of perspectives and professional backgrounds were captured (family physicians, psychiatrists, nurses, pharmacists, genetic counsellors, medical geneticists, lab technologists, private insurers, BC Ministry of Health personnel, and program directors within BC health authorities). Relevant positions and/or specific individuals were identified by the study team and potential participants were contacted individually via email or telephone and invited to participate. Participants provided written informed consent prior to the study interview.

Participants completed one-on-one semi-structured interviews from their workplaces or homes via BlueJeans videoconference software, with a research genetic counsellor; no other observers were present. PWLE were interviewed by CS; P/HCPs were interviewed by EM (both MSc, female; trained in qualitative and quantitative methods with 5 + years of professional research experience). CS had no prior relationships with PWLE participants; EM was a colleague of one P/HCP participant and had interacted in a professional capacity with two others (clinicians and program directors) through her experience working as a genetic counsellor in BC. Participants were informed of the purpose of the research and of the interviewers’ roles as research genetic counsellors. Interviews comprised open-ended questions exploring participants’ perceptions of, experiences with, and opinions and attitudes around PGx testing for depression and its potential use in BC. As data collection and analysis progressed, interview guides were refined (with the input of CS, EM, LE, AMH, GL, LR, LR, and JA) to ensure emerging areas were captured in subsequent interviews. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and checked for accuracy before being analysed. NVivo 12 was used to store, organize, and manage data. 27

Analysis

Interview data were analysed concurrently with data collection using interpretive description,28,29 an inductive qualitative approach that aims to understand the range of subjective human experiences to develop clinical understanding in an applied healthcare setting. The two groups of interviews were largely analysed separately by CS and EM (as described below), but salient themes and similarities/contrasts between the two groups were discussed by CS, EM, and JA on a biweekly basis. The frame of reference for this study was the Sustainability of Innovation model, which considers five domains that influence health innovation sustainability (political, organizational, financial, workforce, and innovation-specific factors). 30 This framework was used to “orient [our] inquiry” 28 by informing the development of our interview guide (i.e., raising factors to explore with participants regarding the implementation of PGx), but was not used as a strict analytical structure (as is typical in interpretive description 28 ).

For each group of interviews, analysis began with inductive line by line coding of basic conceptual units and to delineate the properties that characterize them. 29 CS and EM each independently developed and applied a coding framework for each group of interviews. These were iteratively revised based on findings from new transcripts and applied to earlier interviews when relevant. Axial coding was then used to identify the main concepts from the coding framework, the conditions that give rise to them and the relationships between them. These concepts were used to inductively develop visual models of how PWLE and P/HCPs think about PGx testing and its possible use in BC – CS, EM, and JA met twice a month for 6 months to modify and verify the main concepts and to discuss the theoretical linkages between concepts. The authors – including patient partners – met on several occasions to review linkages and discuss the connections and relationships between relevant concepts for each group of interviews until the major concepts formed a cohesive theoretical model. Throughout the analytical process, written memos were used to capture decisions regarding the data and to record salient themes. Transcripts, codes and memos were iteratively reviewed to discuss and resolve discrepancies. Rather than aiming for “saturation” as a recruitment end point (which has been criticized as a concept in qualitative research for a variety of reasons), 31 we employed the concept of theoretical sufficiency, which asks whether the model constructed is adequate in terms of the use for which it was envisioned. 32 Member checking was conducted with two participants from each cohort. Small adjustments were made to the PWLE model; no changes were made to the P/HCP model after member checking.

Results

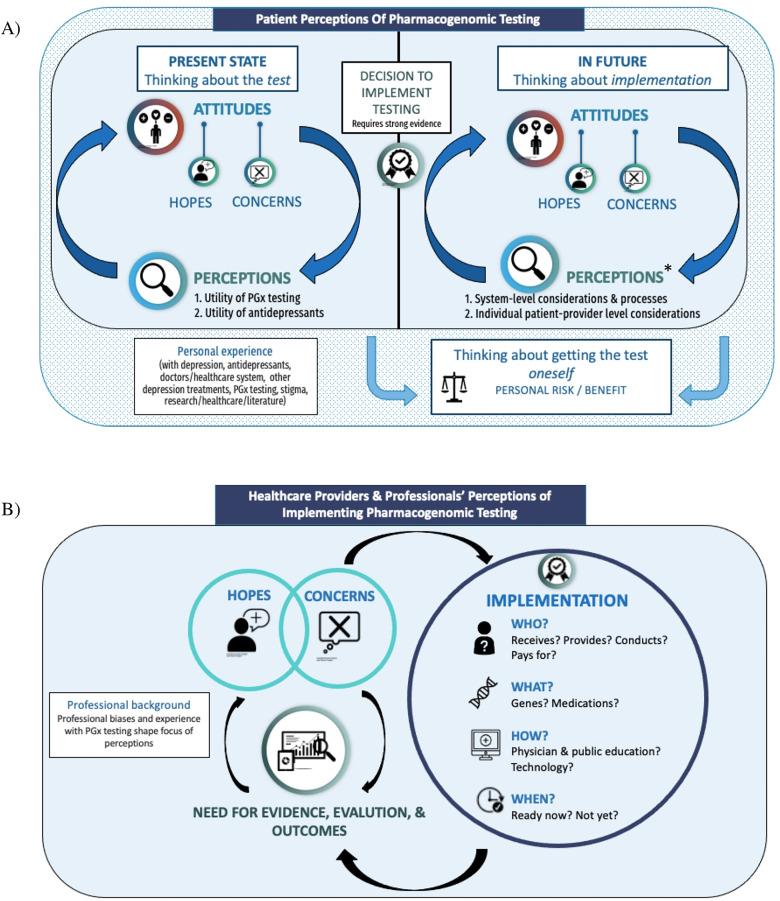

Visual models representing how PWLE and P/HCPs perceive PGx testing for depression were developed; see Figure 1 and descriptions below.

Figure 1.

Depiction of study purpose: to describe how the attitudes and perspectives of PWLE and P/HCPs shape the move towards the clinical implementation of PGx to maximize benefits/mitigate harms within the realities of a publicly funded healthcare system.

PGx = pharmacogenomic; PWLE = people with lived experience; P/HCP = healthcare providers and policy experts.

PWLE

Participants

Seventeen interviews were conducted (Feb–Jun 2021) – with 7 individuals who had previous PGx testing for antidepressant response and 10 without PGx testing experience (see Table 1). Participants were between 21 and 77 years of age, and most identified as women (N = 11) and as White (N = 12). Four of the five regional health authorities in BC were represented across participants. Interviews averaged 62 min in length (range: 38–103 min).

Table 1.

Demographic Information for PWLE and P/HCP Participants.

| PWLE (N = 17) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Women | 11 |

| Men | 6 |

| Age range | 21–77 years |

| Race a | |

| White | 12 |

| South Asian | 3 |

| Mixed | 2 |

| Had PGx testing? | |

| Yes | 7 |

| No | 10 |

| Health authority | |

| Vancouver Coastal | 6 |

| Fraser | 7 |

| Interior | 3 |

| Island | 1 |

| Northern | 0 |

| Education level | |

| High school | 2 |

| Attending university | 2 |

| Diploma/Associate degree | 4 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 7 |

| Graduate degree | 2 |

| P/HCP (N = 15) b | |

| Gender | |

| Women | 9 |

| Men | 6 |

| Race | |

| White | 10 |

| Southeast Asian | 2 |

| East Asian | 1 |

| Middle Eastern | 1 |

| Mixed | 1 |

| Professional role | |

| Clinical c | 9 |

| Psychiatrist | 3 |

| Pharmacist | 2 |

| Family Physician | 2 |

| Genetic Counsellor | 1 |

| Nurse | 1 |

| Lab (public and private) | 2 |

| Policy/Leadership | 2 |

| Private Insurance | 2 |

Note. PGx = pharmacogenomics; PWLE = people with lived experience; P/HCP = healthcare providers and policy experts.

Participants were asked about their ethnic background; data are presented as race categories to match how participants self-described.

The interviewer EM had previously met several of the P/HCP participants but did not know them well (with one exception). This degree of familiarity could have influenced the interviews, but we suggest that this influence would be positive, in that the acquaintance might have allowed more candid conversation.

7 out of 9 participants in clinical roles had experience with discussing PGx testing with patients in some capacity; 2/9 had no experience discussing PGx testing.

PWLE model

Participants discussed the present state of PGx testing, its potential use in BC, and their personal process of evaluating PGx testing for themselves (see Figure 2(a)). Illustrative quotes are included within Table 2. Though PWLE's perspectives were influenced by their past experiences, the themes presented were expressed by both those with and without PGx testing experience. Hopes, concerns, and perspectives that were expressed by people without testing experience were also expressed (based on experience, or theoretically) by people with testing experience. Participants in each group had a range of attitudes and perspectives regarding the use of this testing.

Figure 2.

Visual models of participants’ perceptions of PGx testing for depression and its implementation in the BC healthcare system. (a) PWLE model. Participants expressed numerous hopes and concerns related to PGx testing for depression, with a distinction between participants’ thoughts about the present state of PGx testing (and whether or not the test itself was useful), and thoughts about the possible future implementation of PGx testing in BC – at which point significantly more hopes, concerns, and needs for effective implementation arose. In each stage (present and future), there was a cyclical relationship between participants’ perceptions (of the utility of PGx testing and/or antidepressants [present] or of the considerations needed for effective implementation [future]) and their attitudes towards testing. Participants also discussed considering having PGx testing themselves, which was distinct from their discussion about PGx testing in general and was not necessarily tied to whether or not PGx testing was implemented in BC. All aspects of the model were heavily influenced by participants’ past experiences with depression, antidepressants and other depression treatments, the healthcare system, PGx testing, and/or experience with research/academic literature or provision of mental healthcare themselves. See Table 2. (b) P/HCP model. Participants described a number of hopes and concerns for PGx testing, which drove the need for robust evidence of clinical utility of PGx testing and further evaluation and outcomes studies. P/HCP participants did not view implementation as a certain point in time (or an endpoint); rather, the need for evaluation was perceived to be ongoing throughout and beyond the implementation process to monitor its effectiveness. The way that PGx testing is implemented – for whom, by whom, which genes/medications, when and how – and the outcomes that result from that implementation would continue to influence P/HCPs’ hopes and concerns around its use. Participant discussions were strongly influenced by their unique perspectives/professional biases; though most participants discussed each aspect of the model, some components were viewed as more important than others depending on participant background (e.g., psychiatrists focused heavily on the clinical criteria that would warrant PGx testing; insurers and policy makers focused heavily on the need for evidence and cost–benefit analyses). See Table 3.

*The numerous considerations for implementation discussed by PWLE participants were directly influenced by their hopes and concerns, and would either mitigate concerns/ensure hopes were realized, or fail to mitigate – or even contribute to – potential concerns. Participants felt that should PGx not be implemented well (i.e., with considerations listed in Table 2), potential harms could include over-reliance on medication, failure to take patient concerns seriously, inadequate exploration or support for other mental health management strategies, and inequitable PGx access and treatment for people in BC. PGx = pharmacogenomic; PWLE = people with lived experience; P/HCP = healthcare providers and policy experts.

Table 2.

Elements, Descriptions, and Illustrative Quotes of the Model of How PWLE Perceive PGx Testing and its Implementation Within the BC Healthcare System.

| Personal experience | ||

|---|---|---|

|

“For myself for example, I had to go through a few – quite a few – different medications to find what was the best for me and even at one point they had me like on a cocktail of things which didn’t work well at all. So these things they could kind of prevent and reduce that by knowing – well you can cross that [medication] off [the list] because that's not going to work.” – Participant 11, woman, has not had PGx testing | |

| Present: thinking about the test | ||

| Hopes |

|

“There's something that can tell me that I can take medication X and it won’t have significant side effects and actually be more effective in terms of things like mood stabilization, I mean, I’m all for it, it's exciting, the prospect.” – Participant 5, woman, has not had PGx |

| Concerns |

|

“It depends on the reliability of the results. So, if you know, this has been out and practiced for five years and we can prove that it's, like, 95 to 98 percent it gives accurate results, then that's going to make it a better thing to do. But it gives you, like, 50 percent, it might be better, it might be worse, then that's more of a risk.” – Participant 10, man, has not had PGx |

| Perceptions |

|

“My understanding is that there aren’t like a lot of studies yet that prove that it's an effective intervention. Like studies with like lots of people and stuff. I think it seems like a fairly new field and I hope that it could be something that would help people.” – Participant 2, woman, has not had PGx “I think that if the medication, if antidepressants were as safe as we’re led to believe, then I would say yes get the testing done to make sure you find the one that works proper for you, because the trial-and-error process is just, it's rough. But until any anti-depressants are proven to be 100% safe and effective, I wouldn’t recommend it no.” – Participant 1, man, had PGx testing |

| Decision to implement testing | ||

| Need for strong evidence |

|

“I think if, you know, if they’re coming to me in the setting of a care provider or, like, a consultation, I’m assuming that it's been tested already and looked at and we have adequate research to support its use at the point of care.” – Participant 5, woman, has not had PGx “I have to be able to look it up somewhere and see that multiple people have looked into it, it wasn’t just like one study with like 52 participants or something. I want to know that multiple people, multiple nationalities, like all over the place.” – Participant 11, woman, has not had PGx “The [studies] that seem the most robust are the ones done by some other impartial party that is not for or against it but give a really kind of abstract view on it. They tend to be the most – best thing. [Not done by someone who's developed the test.] And equally not by someone who feels angsty against it and they're trying to prove it in some way. If it's a very impartial review.” – Participant 10, man, has not had PGx |

| Future: thinking about implementation | ||

| Hopes |

|

“If I find out that certain chemicals work better with my body versus other things, that cuts out – I mean […] what an amazing opportunity for someone [to] know exactly what it is that they can use rather than going through the trial and error and have it affect, you know, home life, job, socioeconomic factors, relationships, all of it.”- Participant 3, woman, has not had PGx “There's a huge array of different types of antidepressants and that was quite overwhelming to start with, to work out. And trying to research that yourself when you're in this horrible state of depression is very difficult to do. So if someone could take a test and go, OK, this one will be best for you, then yeah, that would be absolutely fantastic. It would be very, very beneficial.” – Participant 10, man, has not had PGx “I think that testing would really contribute to alleviating what stigma is left or, you know, I do think that would help for people to see it through a more medical light, which it is a medical illness, you know.” – Participant 9, man, has not had PGx “[The PGx result] makes me feel a little bit better that I should be on medication and I am. Yes, it was [validating]… I thought well what is it about me and my case that they’re using [a given medication] and, yeah, so I felt better about that.” – Participant 12, woman, had PGx testing “I think making it more clinical… rather than psychologically based. If they're like, look, you have blood values or a genetic test that tells us that you could benefit from this medication, people might be more willing to consider it.” – Participant 4, woman, has not had PGx “The government is covering [my medications] through Plan G anyway and - I think the case around this is the health economics that would you rather cover me for 20 years and I’m on all these different psychiatric drugs or find out exactly what it is I need. And I think it can also cut down on mental health crises as well, that takes the burden off people being hospitalized.” – Participant 3, woman, has not had PGx “It just I think will allow physicians to be more directive and clear about what they're offering to patients. I think it will save time for physicians. They aren’t going to be mucking around, trying to find the right match for the patient right. At least it's a guide, it might not be fool proof, but at least at it'll tell physicians what to completely stay away from.” – Participant 15, woman, had PGx testing “When you're testing for mental health issues I think that there's also a better chance you can find out whether it is a depression related to, you know, a chemical imbalance in the brain or is this something related to something else going on in the body.” – Participant 9, man, has not had PGx “I also thought, some of the pharmacogenetic testing would revolve around sort of finding your genetic markers, other than metabolism, in terms of a predisposition sort of thing. What genes are responsible for what.” – Participant 14, woman, had PGx testing |

| Concerns |

|

“I wouldn't want to see it become something for the privileged, you know, because that's just depressing in itself… just another thing inaccessible to people with disabilities, people living in poverty.” -Participant 9, man, has not had PGx “It would have to be more validated to be helpful for everybody, especially because Vancouver is so diverse with people from all over the world, not just white people. Because equity wise -I just know how much these things don’t translate to people of African descent or even East Asian, South Asian, so many things just don’t cross over. So I'm worried about that.” – Participant 4, woman, has not had PGx “I think one negative consequence is that a lot of people, including myself are worried about is that our genetic information getting to the wrong hands and being used to increase our [insurance] premiums and whatever. So I personally don’t feel secure with going to Ancestry or 23andMe.” – Participant 4, woman, has not had PGx “What happens if my genetic make-up happens to be like the one that doesn’t agree with [multiple] medication[s]… then all of a sudden like my options have just narrowed so much or maybe they’ve completely disappeared – who knows? So yeah, it could definitely be a scary thing.” – Participant 11, woman, has not had PGx “There's a lack of psychiatrists. Very difficult to find a psychiatrist and, you know, I think we just need more resources available to more people in general. And I think that the sooner that can get in place, the easier it’ll be for things like say pharmacogenetic testing to be used because the infrastructure will be in place. But it's not really in place now, it's really inadequate now.” – Participant 2, woman, has not had PGx testing “My fear is [that] somebody who's becoming someone's physician might, or working locum for the physician, might see [PGx testing results] on a file and, you know, not take other health issues seriously. You know, that would also be my fear for people because there are a lot of doctors who just won't take you seriously when they find out you have a mental illness, you know.” – Participant 9, man, has not had PGx “Yes, there is room for that testing, [but] it's not here when they walk in. That means that we are already pre determining that medication is the solution. And maybe there are other alternatives that we go through. But I don't think that the doctors have that path. It should be mapped out for them… there's a checklist. You're not going to get this done in 12 min, yet, the decision is being made in 12 min whether to put the person on a medication or not.” – Participant 13, man, had PGx “I guess on the terms of eugenics – if you’re able to trace a certain type of depression to a certain gene, then people might worry, well, then, are we going to be trying to modify, like, embryos? And doing something with that specific gene and something like that, along those lines.” – Participant 7, woman, has not had PGx “I'm worried that hypothetically if down the road … [if] the data is in a database, like PopData or something, that anyone can have access to, I'm worried that people might draw conclusions about certain – like the different genders, different identities, different races about like oh well, this group of people are way more likely to have anxiety or these people are genetically predisposed to have depression -and make these broad sweeping statements and generalizations… Stuff like that, it would kind of further entrench maybe some fears that people have about different populations.” – Participant 4, woman, has not had PGx |

| Perceptions |

|

“I think the greatest benefit might be for people who have treatment resistant depression, or maybe there's too many comorbidities to manage that it becomes really hard, then go for it. Or if the clinical picture is very, very complex, then testing is great, I think.” – Participant 5, woman, has not had PGx “Definitely for someone who's just starting [antidepressants]. I think that's a definite. But then the people that are on, it's the risk versus reward thing.” – Participant 10, man, has not had PGx “I feel like it could be beneficial to everybody who struggles with their depression or anxiety even… and then, especially for people who have maybe tried one or two different medications and they’re not really having any luck. I think they could benefit from it the most.” – Participant 7, woman, has not had PGx “Who's liable? I mean, you know, if it goes to the States [for the testing], I would hope that [the BC health authority would] take some level of responsibility for the safety of this information. I mean, it would be ideal if we could establish that infrastructure within the province, or even Canada… Because then you know that it's being governed by Canadian laws. Because it's not going outside the country.” – Participant 5, woman, has not had PGx “I think it should be covered, given that we know the burden of disease when it comes to things like depression. Many people are going to need it, and if they want to make it accessible, we need to cover it 100% by MSP.” – Participant 5, woman, has not had PGx “There's people who don’t have that trust, right? There's communities that that trust hasn’t been established. So, there, you need to do a lot more work, you know, things like cultural safety… [and] I think it might be worth it to make the point that big pharma isn’t a player in this.” – Participant 5, woman, has not had PGx “I don’t believe that drugs in and of themselves are a sufficient remedy for mental illness. You know, there's a lot more to it, there has to be some therapeutic intervention, [… you] can’t just rely on drugs. It's insufficient really.” – Participant 6, woman, has not had PGx “If the results came back and it was just a lot of technical information about this level of my, you know, blood whatever is this number I wouldn’t know all of that – but if the result came back and it said, you know, this brand is the best for you and then these ones might be the next ones, then yeah, that's – that would be understandable information.” – Participant 10, man, has not had PGx “Trying to explain it in ways that I would understand, would be great. Because if you're with your GP and they explain something… [I’m] going in my head, what the hell does she mean by that? And then I would get home and I’d go on my phone, and then I figured out. Maybe even have a discussion prior to the test, to explain what all of these things mean, before you do the test. And then when you do it, you still have something sitting in your head and residual of what you learned. And going to the test results, you have some idea what the doctors talking about.” – Participant 17, woman, had PGx testing “I think that there would have to be some really good education around it – because we’re always excited when something new and shiny comes out, you know, it doesn’t matter what it is. But giving it that – like meeting the expectations. Like really, you know, explaining it really well to people and really making sure that they have an understanding of what it can do, what the limitations are and what's the reality.” – Participant 3, woman, has not had PGx “It would be really great if whoever you have already on your team is involved, like for me my psychiatrist would be involved. But I also think that, you know, I’m taking [other] medication that some of the side effects is depression and sleeplessness and all that kind of stuff, so I think it would be really important to involve [that specialist]. So I would say like whoever is on your care team needs to know that this is happening. …[But]I had a GP probably about 10 years ago who was very judgmental and put up a lot of barriers for me. So, yeah, it's going to depend, right, and it's do people feel safe enough to involve their care team, do they want their care team to know. I think this has to be a psychiatrist thing or a GP thing to start off with and then if I want my care team to know, I think I have to have a choice if I want to expand it out. Some flexibility and choice.” – Participant 3, woman, has not had PGx |

| Thinking about getting the test oneself | ||

| Personal risk/benefit analysis |

|

“If there was, like, strong evidence for it I might consider it. But then, I need, like, six months of good mental health before I try changing anything else, you know. So, maybe I would, if it said this other med would be way better for you, then I could see potentially waiting to a stable time and then trying to switch over to it. But if it's, like, this one might be better, or this one might be 10% better, 30% better, I don’t know. Or, I don’t know, I guess 30% would be a big difference. But you know what I mean, I’d have to think about it. But it could be useful.” – Participant 8, man, has not had PGx “I think for me, for me I would want to do it because I would want to make sure that I’m doing the right thing and not going to have this huge whole long process that was coming down off this one and then increasing this one and then coming down off that and then increasing a new one. Yeah, I would definitely just do it to help save some time and just protect your body.” – Participant 11, woman, has not had PGx |

Note. MH = mental health; MoH = Ministry of Health; PGx = pharmacogenomic; PWLE = people with lived experience.

Genetic discrimination was not a large source of concern for the majority of participants, with some expressing that they were already discriminated against because of their depression diagnosis. Concern about genetic discrimination was sometimes based on a perception that PGx testing might reveal risk factors for other disorders (e.g., “one of the breast cancer genes”).

Participants discussed existing challenges accessing appropriate mental health care in BC and how those challenges may present during, or be exacerbated by, the pursuit of PGx testing. While some participants described feeling sufficiently supported to access and make decisions about PGx testing, they acknowledged that many other BC residents did not have those same resources; other participants discussed their own personal challenges accessing care and how they imagined that might impact PGx testing access or the application of PGx test results.

Concerns about genetic discrimination and/or secondary uses of genetic information would be somewhat mitigated if data were to remain in BC/Canada.

The majority of participants – even if they were willing or able to pay for PGx testing out-of-pocket – wanted the BC Medical Services Plan (MSP) to cover the cost of testing for eligible patients in order to ensure equal access to testing and appropriate follow-up care.

Participants varied in the type and source of desired support for PGx testing: many participants wanted to access testing through their GP, either due to ease of access or because of existing trust and familiarity. Others acknowledged that accessing testing through a GP would be difficult because “there are so many people in BC that don’t have GPs,” or thought that PGx testing required more psychopharmacological expertise and should be facilitated by a psychiatrist. Still others wanted every member of their care team (e.g., clinical counsellors or other medical specialists) kept informed of their PGx test results; or wanted minimal support from healthcare providers, with an option to consult one's GP or an “expert” (like a pharmacist, genetic counsellor) if needed.

Present: thinking about the test

Participants described a cyclical relationship between their hopes and concerns about PGx testing, and their perceptions of utility of both PGx testing and antidepressants. Perceived lack of utility of PGx testing, and/or the perception that antidepressants should not be routinely used seemed to reduce hopes or increase concerns about the testing. Perceived utility of PGx testing and/or antidepressants bolstered hopes and reduced – but often did not eliminate – concerns. Many participants had mixed views.

Decision to implement testing in BC

Participants expressed the need for an authority – such as the BC Ministry of Health, doctors, and/or scientists – to evaluate the literature and decide that there was enough evidence to support the implementation of PGx testing. Despite a general trust and reliance on professionals to make this decision, participants wanted the research evidence to meet standards of rigor and to be available to the public, to potentially aid in personal decision-making.

Thinking about future implementation

As compared to thinking about the test itself, thinking about implementation evoked a greater number of hopes and concerns for participants (see Table 2), which were described with greater emphasis. There was a general feeling that “the testing itself is one thing, and the use of results is entirely different.” Participants discussed both individual-level benefits and risks, such as a person experiencing therapeutic benefit or emotional distress (e.g., from a disappointing result), as well as broader considerations like benefits to the healthcare system and concerns about unequal access to testing (see Table 2).

Thinking about getting the test oneself

Participants also discussed their own decision-making around PGx testing as a risk/benefit assessment of the relative importance of their concerns, hopes, and the current state of their mental health (Table 2).

P/HCPs

Participants

Fifteen interviews were conducted (Oct 2020–Jul 2021) with professional stakeholders in various clinical (N = 9), laboratory (N = 2), policy (N = 2), or health insurance (N = 2) roles (see Table 1). Most participants were White (N = 10); 9 participants identified as women, 6 as men. Interviews averaged 43 min in length (range: 24–59 min).

P/HCP model

Participants discussed their hopes and concerns for PGx testing, the need for outcomes data and evaluation, and considerations for implementation (see Figure 2(b)). Illustrative quotes are included within Table 3. Details about participants’ professional roles are omitted from quotes to protect participant anonymity.

Table 3.

Elements, Descriptions, and Illustrative Quotes of the Model of How P/HCPs Perceive PGx Testing and its Implementation Within the BC Healthcare System.

| Hopes and concerns | ||

|---|---|---|

| Hopes |

|

“I'm hugely, hugely supportive of it because it [could be] life changing for patients in terms of them avoiding all of the trial and error and all of the adverse effects that they often experience with these drugs because they have a lot of adverse effects….. And so you get them on the right drug and the right dose, you avoid the adverse effects and they're likely to be a lot more adherent to the therapy as well. So you get kind of a double win.” – Participant 6 “People that have refractory depression, you know, they have to stay in tertiary environment, very costly. They’ve had multiple medication trials without a lot of success. And I think there might be some utility there as well… preventing hospitalization, duration of hospitalization, decreased experience of side effects… I'm very optimistic that it will show utility.” – Participant 1 “The nice thing about pharmacogenomics, or any genomic testing, is it's a lifetime thing. Your DNA doesn't change, right, so you don't need to do it again. And so, in the future, if you ever prescribe something new, we could fall back on the test and relook at it and say, "Well what about this? What if we did this?" … We've always got that information available to us. It's now a new tool that's always in our toolbox, never going to go bad.” – Participant 6 “Maybe just the sensitivities around mental health and unfortunately it's still a little bit taboo, which amazes me that it is this day and age… I’d hope it would make it better. I’m just thinking for an individual patient, no I think it would make it better, because it's an understanding a bit more of their makeup their genetics.” – Participant 11 “It offers some opportunity, I think, in those few cases to – you know, if I was going to recommend sertraline or fluoxetine and they had testing results suggesting there's a higher level of confidence for them in sertraline…, there's some added benefit in supporting that. Just in terms of their psychological state of mind around this. That you know the potential success of that – that trial and their willingness to pursue it.” – Participant 8 “I think the more information the patient receives about their medication the more likely they will be compliant to it.” – Participant 1 “I would say making a difference, in terms of informing the treatment directly, I would say 50% [of the time PGx testing resulted in a change in the medications prescribed]. The other 50, it did not lead directly to make any changes right away, but it did inform our discussion. So, the information was helpful in the clinical process and deciding. And so, it did add some certainty about those factors not being the cause. And that sometimes is also helpful.” – Participant 5 “Well, so the first value is that they are seeing that the doctors are trying, or the pharmacists, actually, are trying to find more information that will help them. And that, in itself, is a positive message that they can see [that the physician is] going that extra mile.” – Participant 3 “I really believe in the non-drug measures first. And so, you know, medications aren’t without adverse effects. Even Tylenol has side-effects, right… But these antidepressants come with some pretty significant side-effects. And so it would be really nice to be able to utilise non-drug measures to be able to try and figure out, well, who would benefit from CBT versus other modes of therapy, perhaps, before going on the drugs. If pharmacogenetic testing can help out with that, that's basically what I’m trying to say is, anything that we can do from a non-drug perspective.” – Participant 14 |

| Concerns |

|

“Well, kind of it's the standard risk that comes with genetic testing, with data handling and kind of all this fine balance between collecting data and storing it safely and not sharing widely or not sharing with the organizations that might be able to use it for profit and an actual benefit, like very clear and very immediate benefits to this particular person.” – Participant 7 “I think the biggest issue – and again, that the insurers have to really think about and consider – there is some federal legislation that has either already happened, or in the process of happening around genetic testing… because there is fear that if insurers know somebody's genetic makeup and test results, and sense that tendency to get disease states, or whatever, it could really change the rating and the risk profile, or even the denial of insurance altogether. And it's not a good risk.” – Participant 15 “In the mental health area, you're dealing with – I found anyway you're dealing with such a more fragile population already, they've usually been through a lot – a lot of different doctors’ visits, a lot of medications and they're just at the end of their rope. They're just like, I just want to be helped….And this [PGx testing] is kind of the last thing to tip them over the edge. Like, paying $500 and getting no additional information and no options for medications because they've tried all of them already.” – Participant 4 “I think that the struggle for a lot of people is how are they going to use this information? Because it is complex. I mean, we talked – I would say 90 percent of physicians can’t even pronounce the variance, CYP2D6, whatever. And so, if we pronounce to them a pharmacogenetic result that is CYP2D6 ultra metabolized, they’re going to go, ‘What do I do with that?’” – Participant 3 “Well the main downside is you know, it's wasting the financial resources right? So if you do the indiscreet testing for everybody that's out there and you're spending a lot of money. I mean I think the labs are charging up to $2,000 per person. That's a lot. You know, that's money that could be used for something else.” – Participant 9 “I think that would be quite confusing for the patient. And that's what I can see like maybe some non-compliance issues possibly with taking medications.” – Participant 11 “I think the worry just comes from, like, that place of not wanting to over promise things to people… that's going to be sort of the answer, but I think it would be great if it was. And so, the ideology behind it is great, but I just don’t think it's quite there.” – Participant 2 “We’re trying to hope that we get quick access. Because that's the other thing, like if somebody is not doing well, we almost don’t want to deny them medication if that's going to be an important part of their recovery… if somebody is really unwell, so I think maybe there needs to be almost a range of, like, how sick is that person and how long is it going to take to get the test results back?” – Participant 2 “I think there's always going to be problems with you know people, requesting to be tested multiple times. And I think that's – that's where we need to say like OK, like it's not going to change because this is your genetics. But then when new medications come out, then they might want to repeat the test, right… I think it should be available to everyone, but maybe on like once every five-year basis or something like that.” – Participant 10 |

| Need for evidence, evaluation, and outcomes | ||

|

“And I would think that a decision about pharmacogenomics is going to be based on the evidence that exist by drug class, by drug. And what is the business case for it… you know whether it's in quality of life years or adjusted life years or whatever, however it gets quantified… there is robust evidence that would have to exist for at least one drug ideally for a couple antidepressant drugs.” – Participant 12 “So you know, you’d have to do all of the analysis of how many types of therapies would they have started and built on prior to doing [Pharmacogenomic testing]? What would be the cost of that, versus the cost of pharmacogenetic testing.” – Participant 15 “I think there's definitely utility, but in order to quantify that utility in the whole Canadian healthcare system, basic scenario, like you mentioned, is that we are going to make major cost saving – we’re going to have major cost-saving outcomes by using these pharmacogenomics. And that actually needs to be shown because we don’t have convincing data currently showing that this can happen by doing this test.” – Participant 1 “I do worry about how these studies are going to be interpreted. And so again, that's why I want it to be at arm's length from someone who's actually going to benefit from the study. So, those are the risks that I see. It has to be regulated, there has to be oversight that is not related to the funding mechanism.” – Participant 14 “So definitely look at the evidence, consult with the experts, talk to people that would benefit from it, from family members as well. And then look to guidelines and things like that, and then follow up. Like, is it working, is it not working, and why not?” – Participant 14 |

|

| Implementation | ||

| Who |

|

“I think, if it becomes widely available, then that would be like something that I would automatically do before I start anybody on a test – on a medication. But, if it was reserved for a select few, then I would say you know basically the people who have not responded to the first or second in line medications.” – Participant 10 “But I think if we concentrate on those who would benefit most, then we could look at the coverage for something like this to be more meaningful, because there's not an infinite amount of money available.” – Participant 14 “From a physician perspective, my thought process is I think physicians are in a good position but I don't think they're in as good a position as pharmacists because they don't understand the medications and the metabolism of medications as well as pharmacists do.” – Participant 6 “So, if all the genetic testing is done in the US, first of all, we’ve got to be very – we are very conscious… our government contracts very clearly dictate that none of our data can reside in the US. So therefore, we would be not inclined to sign contracts with companies that do pharmacogenetic testing in the US, because we would be giving personal health information about Canadians to that company.” – Participant 15 “Right now, it [the cost of PGx testing] is being [born] by the patients and we are struggling with, “Are we at that tipping moment where the health service should pay for it?” We’re right in-between. We are at the place where the insurance companies are paying for it. And then it will move to the health system.” – Participant 3 |

| What |

|

“[We should list] these are all the drugs that we think are important to look at from a substrate perspective and if you're being prescribed any of these drugs, then you would qualify to get [testing]…. And that might be a really good way because not every mental health drug has enough PharmGKB level one or, two evidence to support that there are actually prescribing guidelines for that drug. It's not every antidepressant.” – Participant 6 |

| How |

|

“Because you can have a test result that shows A, B, C, but what does it mean for the patient? And I think that's the hard part, is sometimes we have to make those connections ourselves, now that we’re in practice. And I – yeah, and I think that's the hard part. Sometimes I’m like, I don't know where to go for this and I don’t know what that means. And so, I think, definitely having something you know like a – kind of like a guideline as to what to do, or at least a resource board to turn to if there was an issue, then I would feel comfortable doing it.” – Participant 10 “It is often just sort of talking about how it's another piece to the puzzle; it may or may not be helpful for them. It may recommend medications for that they’ve already tried. And so, it's just sort of expectation setting is what I feel like I end up doing around it, that it's sort of not the magical answer that it's going to tell them what medication they should take.” – Participant 2 “Well, you know I think if we’re going to do that then we have to have information and resources available for families in plain language to help them understand, you know what this is about, what the results mean. And you know what the risks and the benefits are.” – Participant 8 “I mean, you’ve got a PDF report that goes into a chart somewhere and, you know, it may change that patient's prescription then, but the likelihood that it will be used throughout is low. So, I think it really comes down to the implementation of the result into the clinical setting being the barrier, not the actual science behind pharmacogenetics or the clinical effectiveness, or even the cost effectiveness.” – Participant 3 “There's a lot of misunderstanding that's out there about its utility for day to day practice. And the reason I suggested [a specialist clinic] is so that we can offer that expert advice you know, if you have a psychiatrist in the community that has a question, that has a patient that needs testing we can do the assessment. And then you know provide information about you know what we know about it.” – Participant 9 “As we think about things like pharmacogenetics testing, or new treatments, you know thinking about those through an ethical framework lens, thinking about that through what we’ve committed to, in terms of anti-racism and anti-Indigenous racism, and structural racism within healthcare, you know… Within delivery of pharmacogenetic testing what are the structural barriers to people of colour? What are the structural barriers to Indigenous peoples and their families?” – Participant 8 “I think about the family living in Dease Lake and the nursing station there, you know. Is this going to be equitably available to them when it's necessary versus the people living across the street from Vancouver General Hospital or Children's Hospital? And you know and that's really important to me.” – Participant 8 “One thing that always kind of gets neglected is like the ethnic groups – yeah, would that be part of the testing?… Often, you know in medicine a lot of the studies are done for white Caucasian males in their 40s and 50s, and everybody else gets excluded, right… So, you know, ethnic groups, pregnant people. Yeah, I think it would be great if we were able to target – or kids, those are the people that often get left out of these studies. So would those things be considered?” – Participant 10 “First of all, there has to be a company, whether it be based in BC or in Canada – and I don’t want to say just BC, but there has to be – for the privacy aspect of it, I think we all have different laws and regulations about data, access to data and the FOIPPA and the PIPEDA legislation is very, very clear on that.” – Participant 15 |

| When |

|

“It's an evolving field. You know, things will change but you can’t wait for the perfect time to start. Because at this point in time you know, you have pharmacists that are spreading false information about it. You have patients that somehow seem to think that they had their physician offer this testing earlier on, they’d have already been you know a lot more better.” – Participant 9 |

Note. PGx = pharmacogenomic; P/HCP = healthcare providers and policy experts; TAT = turnaround time.

Factors that were perceived as both a hope and concern by different participants, or were countered by other participants’ statements. For example, while there was a general hope that PGx testing would result in reduced time to medication response/therapeutic benefit, participants also acknowledged that the turnaround time for PGx testing might actually delay treatment.

Several participants expressed a belief that PGx testing would turn out to be cost effective in terms of reducing the strain on the healthcare system, despite the current lack of evidence. One participant also discussed the societal burden of depression far outweighing the cost of any medication, and the need to include societal costs in future cost–benefit analyses.

A number of participants felt that ideally, PGx testing should be offered to any patient beginning their first antidepressant trial to potentially avoid multiple failed medication trials. From a laboratory perspective, this could also help reduce the cost of testing per patient with batching large numbers of samples for genetic analysis. Others felt strongly that PGx testing should be limited to certain subsets of patients – for example, people with treatment-resistant depression – because clinical utility or cost effectiveness may be limited to certain groups, or because population-wide testing is not feasible.

There was no consensus on which HCP would be the best provider of PGx testing. Tension arose between the need for an established relationship with the patient and knowledge of the full clinical picture in order to make “holistic” treatment decisions (such as the relationship between a patient and a GP or psychiatrist), versus having sufficient time, knowledge or accessibility to have fulsome discussions with patients. Several participants suggested that other practitioners would offer specific advantages: a genetic counsellor (genetic expertise, time), a pharmacist (pharmacological expertise, time, accessibility), or a community nurse or nurse practitioner (existing relationship with patients, time, and accessibility); however, each of these clinicians were perceived to have areas of weakness as well. Other suggestions included a small-scale introduction of PGx testing which could then be expanded with time; integration of genetic counsellors into primary care/psychiatry; or having a specialist multidisciplinary PGx clinic.

Patient access was a major concern for several participants, who discussed the need to have anti-racist structures in place to provide equitable care for Indigenous people, Black people, and people of colour – such as ensuring equal access for patients in rural/Northern BC, or cost coverage in order to avoid a “two-tiered” healthcare system.

Some participants thought testing should not proceed unless there was sufficient evidence of utility; others were confident that this was a question of when (not if) sufficient evidence would be amassed and implementation could proceed – though this notion seemed to be driven by a general sense of optimism rather than any concrete evidence. Finally, some participants felt that since PGx testing was already occurring with or without the BC healthcare system's involvement, there was an imperative to provide the testing in a safe and regulated manner within BC.

Hopes and concerns

Participants discussed their hopes and concerns for the use of PGx testing (see Table 3), the most prominent of which were hope for therapeutic benefit, concern about the cost of testing, and whether a favourable cost/benefit ratio could be achieved. Participants’ hopes and concerns were sometimes in conflict with each other. For example, some participants thought PGx testing could help, while others thought it may hinder medication concordance.

Need for evidence, evaluation, and outcomes

The need for evidence and evaluation of PGx testing was raised by most participants and was a recurring point of discussion for several participants. This included the need for evidence to support participants’ hopes and the clinical utility of PGx testing (improved patient outcomes) and validity of concerns, as well as evidence to disentangle conflicting hopes and concerns (e.g., whether PGx testing could help or hinder medication concordance). Of particular importance was the need for a conclusive economic analysis, which participants perceived to be currently lacking in the literature.

Implementation

Participants expressed numerous considerations around Who, What, How, and When PGx testing should be implemented (see Table 3), with a focus on mitigating potential harms. For example, participants expressed a need for pretest counselling due to the perception that patients with depression were a vulnerable population that needed to be protected from false hope or unrealistic expectations of PGx testing. However, the ways in which participants thought harms should be mitigated were varied and influenced heavily by professional background.

Discussion

This is the first study to explore the perspectives of both PWLE and professional stakeholders on PGx testing for depression and its potential implementation in a Canadian context. There was both overlap and differences in perspective between PWLE and P/HCPs, as represented in the models. The visual models describing how PWLE and P/HCPs think about the potential introduction of PGx testing in BC can be used to inform the development of implementation strategies that have the best chance of being acceptable and effective within the realities of a public healthcare system.

A major, recurring concern for PWLE and several P/HCP participants was that (assuming appropriate evidence for effectiveness) PGx testing should be paid for through the publicly funded healthcare system. As in a previous Canadian study about PGx that was not specific to depression, 33 many participants were concerned about the potential for inequitable access to testing. There was worry that if PGx were to be available only to those who could private pay, and/or those in urban centres, this could further contribute to inequitable healthcare access and outcomes. The cost of PGx testing – and patients’ means to pay for it – has been cited as a top barrier to implementing PGx. 14 This was also a concern for patients who had previously undergone PGx testing for depression, several of whom thought the test would only be worth taking if it was less expensive. 22

Consistent with previous reports of patient22,34 and provider20,21 perspectives, both PWLE and P/HCP participants were hopeful about the potential therapeutic benefits of PGx testing: faster recovery/symptom reduction, fewer side effects, and reduction in the current practice of trial-and-error prescribing. Both cohorts were also hopeful that PGx testing could result in cost savings for the healthcare system through reductions in mental health crises and hospitalizations. However, we also heard that there would be potential meaningful value of PGx testing even without treatment changes. For example, PWLE said PGx results could validate past experiences with antidepressants and/or current treatment approach (or already had provided validation for several participants with PGx testing experience), while P/HCPs hoped that PGx testing might increase patients’ comfort with taking a medication or their trust in the prescribing clinician.20,21 Both PWLE and P/HCPs also expressed that PGx testing could help validate depression as a legitimate medical condition and thus provide value on a societal level (in terms of decreasing stigma) regardless of its impact on individual treatment decisions.

The development of clinical practice guidelines or resources for P/HCPs to enable them to utilize PGx testing effectively for their patients was identified by both groups in our study, and in previous work14,33 as crucial. Some clinicians expressed that they/their colleagues have limited knowledge of PGx testing (consistent with previous reports16,17,21) or limited time with which to invest in significant interpretation efforts. Concern among patients about the lack of clinical guidelines is a novel finding. Our PWLE (and some P/HCP) participants were concerned that without guidelines, prescribing clinicians might over-utilize PGx testing – and therefore, antidepressants (a concern that has previously been reported 23 ). Participants wanted clinicians to work with each individual in a “holistic” manner, with consideration of patient preferences or lived expertise in their own care and other avenues for mental health management (e.g., therapy). 35

In previous Canadian research in which patients, providers, and policy-makers discussed PGx testing in primary care (not specific to depression), concerns were expressed about genetic discrimination. 33 In contrast, many PWLE participants expressed that the potential for genetic discrimination could not be worse than the discrimination they had already experienced as a result of having depression. If discrimination was raised, it was sometimes connected to misconceptions about what PGx testing would uncover – for example, risk factors for other conditions – suggesting that patients may be confusing PGx testing with predictive testing for susceptibility to illness.23,25 In both PWLE and P/HCP participants, this misconception was also sometimes perceived in a positive manner, in the hope that PGx testing will “explain” their depression. This highlights the need for provider education and pretest counselling to manage expectations and/or concerns about testing.

A number of specific requirements for the effective implementation of PGx testing were expressed by both PWLE and P/HCPs. Both groups emphasized the need for physician education (to enable appropriate ordering and interpretation of PGx testing), patient education (to manage expectations and ensure informed consent/autonomy), testing facilities and infrastructure within BC or Canada (to ensure data privacy and security), and accessible test reports (for patient and clinician understanding of results). P/HCP participants also discussed the need for technological support and clinical protocols. PWLE discussed the need for emotional support for patients through the testing process (if desired), and the need for appropriate and available psychiatric care – a much larger issue in the BC healthcare system that would inevitably affect patient access to PGx testing and subsequent treatment. While PWLE generally trusted that the decision to implement PGx testing would be informed by strong evidence, P/HCP participants discussed the need for ongoing systemic evaluation and outcomes monitoring to continuously support implementation within BC and mitigate concerns about the use of PGx testing.

Opinions varied on exactly how, or through whom, patients should access PGx testing. While family physicians were discussed as a desirable option due to accessibility and an established patient–provider relationship, a number of participants (both PWLE and P/HCPs) had concerns about family physicians’ time and ability to fully educate and support patients throughout PGx testing. Some thought testing should be provided through psychiatrists, but many others thought this would create unnecessary barriers to access. Still others wanted clinical experts – such as genetic counsellors, pharmacists or psychiatrists – available as needed for consultation. Regardless of which provider PWLE wanted to facilitate testing, this was often based on the existence of a trusting relationship, echoing previous reports in the PGx for depression 24 and general PGx literature. 36

P/HCP participants repeatedly discussed the need for conclusive economic analyses – which has been called for numerous times both in the context of PGx for depression9,20 and PGx testing more generally.33,36 We agree that further investigation into the accessibility, effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness (including societal costs) of different implementation strategies for PGx testing is needed. Indeed, our findings are being used to inform the development of a simulation model of the cost-effectiveness of PGx testing for major depression in BC.

Limitations

Our cohort is not fully representative of the BC population and is limited to people who had computer access and were engaged in social media or research networks. Both cohorts were largely White, and the perspectives of Indigenous people, Black people, and people of colour are absent. Future areas of study should prioritize engagement with Indigenous communities of BC and the co-creation of PGx research priorities, protocols, and knowledge.

Our models of how PWLE and P/HCPs perceive PGx testing for depression were developed from the experiences and perspectives of residents of BC, and are thus specific to our healthcare context. However, they provide useful starting points for the consideration of clinical implementation of PGx testing for depression in public healthcare settings.

Conclusion

PWLE and P/HCPs have numerous hopes, concerns, and opinions on how PGx testing should be implemented in BC. PWLE generally trust that the decision to implement testing will be based on sound evidence, but want the evidence to be robust and made available to them for personal decision-making. PWLE also want the plan for PGx implementation to ensure low-barrier, equitable, and effective access to testing for eligible patients. P/HCPs were also hopeful about the potential for therapeutic benefit from PGx testing, but see the need for ongoing outcomes evaluation and monitoring to ensure that PGx testing is introduced in a balanced and cost-effective manner.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-cpa-10.1177_07067437221140383 for Pharmacogenomic Testing for Major Depression: A Qualitative Study of the Perceptions of People with Lived Experience and Professional Stakeholders by Caitlin Slomp, Emily Morris, Louisa Edwards, Alison M. Hoens, Ginny Landry, Linda Riches, Lisa Ridgway, Stirling Bryan and Jehannine Austin in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-cpa-10.1177_07067437221140383 for Pharmacogenomic Testing for Major Depression: A Qualitative Study of the Perceptions of People with Lived Experience and Professional Stakeholders by Caitlin Slomp, Emily Morris, Louisa Edwards, Alison M. Hoens, Ginny Landry, Linda Riches, Lisa Ridgway, Stirling Bryan and Jehannine Austin in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the study participants and offer gratitude to the Coast Salish Peoples, including the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), and Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations, on whose traditional, unceded, and ancestral territory we have the privilege of working.

Data Access: Data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by Genome BC and Genome Canada (project #B26PMH) and Michael Smith Health Research BC (award #18932). JA was supported by BC Mental Health and Substance Use Services.

ORCID iDs: Caitlin Slomp https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4063-2937

Jehannine Austin https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0338-7055

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Lam RW, Kennedy SH, Grigoriadis S, et al. Canadian Network for mood and anxiety treatments (CANMAT) clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. J Affect Disord. 2009;117:S26‐S43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeier Z, Carpenter LL, Kalin NH, et al. Clinical implementation of pharmacogenetic decision support tools for antidepressant drug prescribing. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175:873‐886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho SC, Chong HY, Chaiyakunapruk N, et al. Clinical and economic impact of non-adherence to antidepressants in major depressive disorder: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2016;193:1‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ta JT, Sullivan SD, Tung A, et al. Health care resource utilization and costs associated with nonadherence and nonpersistence to antidepressants in major depressive disorder. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2021;27:223‐239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herbild L, Gyrd-Hansen D, Bech M. Patient preferences for pharmacogenetic screening in depression. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2008;24:96‐103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maruf AA, Fan M, Arnold PD, et al. Pharmacogenetic testing options relevant to psychiatry in Canada: options de tests pharmacogénétiques pertinents en psychiatrie au Canada. Can J Psychiatry. 2020;65:521‐530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luzum JA, Petry N, Taylor AK, et al. Moving pharmacogenetics into practice: it’s all about the evidence! Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2021;110:649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohn I, Cohn RD, Ito S. Professional opportunity for pharmacists to integrate pharmacogenomics in medication therapy. Can Pharm J (Ott). 2018;151:167‐169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zanardi R, Manfredi E, Montrasio C, et al. Pharmacogenetic–guided treatment of depression: real-world clinical applications, challenges, and perspectives. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2021;110:573-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ontario Health. Multi-gene pharmacogenomic testing that includes decision-support tools to guide medication selection for major depression: recommendation. Toronto (ON): Queen's Printer for Ontario; 2021. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenblat JD, Lee Y, McIntyre RS. The effect of pharmacogenomic testing on response and remission rates in the acute treatment of major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2018; 241: 484‐491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown LC, Stanton JD, Bharthi K, et al. Pharmacogenomic testing and depressive symptom remission: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective, controlled clinical trials. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2022. doi: 10.10002/cpt.2748. Online ahead of print. Accessed Oct 18, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tiwari AK, Zai CC, Altar CA, et al. Clinical utility of combinatorial pharmacogenomic testing in depression: a Canadian patient- and rater-blinded, randomized, controlled trial. Transl Psychiatry. 2022;12:101-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown L, Eum S, Haga SB, et al. Clinical utilization of pharmacogenetics in psychiatry – perspectives of pharmacists, genetic counselors, implementation science, clinicians, and industry. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2020;53:162‐173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Volpi S, Bult CJ, Chisholm RL, et al. Research directions in the clinical implementation of pharmacogenomics: an overview of US programs and projects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;103:778‐786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shishko I, Almeida K, Silvia RJ, et al. Psychiatric pharmacists’ perception on the use of pharmacogenomic testing in the mental health population. Pharmacogenomics. 2015;16:949-958. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Chan CYW, Chua BY, Subramaniam M, et al. Clinicians’ perceptions of pharmacogenomics use in psychiatry. Pharmacogenomics. 2017;18:531‐538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson C, Hamilton SP, Hippman C. Psychiatrist attitudes towards pharmacogenetic testing, direct-to-consumer genetic testing, and integrating genetic counseling into psychiatric patient care. Psychiatry Res. 2014;226:68‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walden LM, Brandl EJ, Changasi A, et al. Physicians’ opinions following pharmacogenetic testing for psychotropic medication. Psychiatry Res. 2015;229:913‐918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunbar L, Butler R, Wheeler A, et al. Clinician experiences of employing the AmpliChip® CYP450 test in routine psychiatric practice. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26:390‐397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vest BM, Wray LO, Brady LA, et al. Primary care and mental health providers’ perceptions of implementation of pharmacogenetics testing for depression prescribing. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20:518-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liko I, Lai E, Griffin RJ, et al. Patients’ perspectives on psychiatric pharmacogenetic testing. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2020;53:256‐261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]