Abstract

Background

Mental disorder is common among prisoners; however, little is known about how illness severity changes during incarceration, and especially to what extent there are different trajectories of change.

Aims

Our aims were to investigate trajectories of illness severity among male and female inmates with serious mental disorders, and to investigate whether clinical or demographic variables are associated with different trajectories.

Methods

We carried out a retrospective cohort study of newly remanded inmates who had three or more serial measures of illness severity as measured by psychiatrists using the Clinical Global Impression—Corrections (CGI-C), and used group-based trajectory modelling to identify trajectories. We investigated whether clinical and demographic variables were associated with different groups.

Results

We found an overall reduction in the severity of illness (mean change in CGI-C score −0.74, SD 1.5), with women showing greater improvement than men. We identified three distinct trajectories among men and three among women, all showing improvement in illness severity. Approximately 15% of the entire cohort had full resolution of symptoms, whereas the remainder showed partial improvement. Women, younger inmates, and those with substance use disorders were more likely to have full resolution of symptoms.

Conclusions

Although most prisoners showed improvement, and a small proportion had full resolution of symptoms, a significant number continued to have moderately severe symptoms. There is a need for comprehensive treatment within the detention centre, but also a need for transfer to hospital for those with severe symptoms as improvement within the correctional setting tends to be modest.

Keywords: gender, prison, longitudinal study, correctional centre, mental health services

Abrégé

Contexte

Le trouble mental est commun chez les prisonniers, cependant, on en sait peu sur la façon dont la gravité de la maladie change durant l'incarcération, et spécifiquement dans quelle mesure y a-t-il différentes trajectoires de changement.

Objectifs

Nous visions à investiguer les trajectoires de la gravité de la maladie chez les détenus masculins et féminins souffrant de sérieux troubles mentaux, et à investiguer si des variables cliniques ou démographiques sont associées à différentes trajectoires.

Méthodes

Nous avons mené une étude de cohorte rétrospective de prévenus récemment placés en détention provisoire qui avaient trois mesures séquentielles ou plus de la gravité de la maladie comme les mesurent les psychiatres à l'aide de l'Impression globale clinique — Services correctionnels (CGI-C), et nous avons utilisé une modélisation d'une trajectoire de groupe pour identifier les trajectoires. Nous avons investigué si les variables cliniques et démographiques étaient associées à différents groupes.

Résultats

Nous avons observé une réduction globale de la gravité de la maladie (changement moyen du score à la CGI-C -0,74, ET 1,5), les femmes présentant une plus grande amélioration que les hommes. Nous avons identifié trois trajectoires distinctes chez les hommes et trois chez les femmes, toutes indiquant une amélioration de la gravité de la maladie. Environ 15 % de la cohorte en entier avait une résolution complète des symptômes, alors que le reste montrait une amélioration partielle. Les femmes, les jeunes prévenus et ceux souffrant de troubles d'utilisation de substances, étaient plus susceptibles d'avoir une résolution complète des symptômes.

Conclusions

Bien que la plupart des prisonniers aient montré une amélioration, et qu'une petite proportion ait une résolution complète des symptômes, un nombre significatif continuait d'éprouver des symptômes modérément graves. Il y a un besoin de traitement complet au centre de détention, mais aussi un besoin de transférer à l'hôpital ceux dont les symptômes sont graves, car l'amélioration en milieu correctionnel tend à être modeste.

Background

A high proportion of prison inmates have mental disorders; one in seven are found to have major depression or psychosis and around half have substance use disorders. 1 Although the prevalence of mental disorders has been well documented, less is known about the severity of symptoms among inmates, and in particular, how illness severity changes during incarceration. Knowledge of the course of mental disorders in correctional centres is of considerable clinical importance to help determine the extent to which the environment may impact mental health, as well as the adequacy of mental health services within correctional centres. Most studies to date have used self-report measures of mental well-being, and have recorded high levels of psychological distress among inmates at the commencement of incarceration,2–7 generally followed by improvement overall. For example, a prospective study in the United Kingdom (UK) of 170 pre-trial male prisoners interviewed twice during the first 4 weeks of incarceration found a reduction among those considered “cases” using the Symptom Checklist 90 (SCL-90) from 72% to 50%. Similarly, a prospective study of 980 inmates in the UK during the first 2 months of incarceration found an overall reduction in the proportion considered cases using the GHQ-12 8 from 33% to 18% among men. The proportion of cases was higher among women in this study, and unlike among men, there was no overall improvement in the mental state during the study period (46% to 50%). 9

Although several studies point to an overall improvement in the mental state during early incarceration, 10 there may be significant variation in experience between inmates. In a study of 136 male inmates in the USA interviewed prior to release, one-third reported an improvement in emotional problems during incarceration, while the remainder reported no change or a deterioration

Limitations in many of the previous studies are that (a) they have included only inmates who could participate in completing structured interviews and questionnaires which would have excluded those who are most symptomatic; (b) many have reported aggregated symptom severity among participants, which may have concealed individual differences; (c), they have mainly employed only two or three serial measures of symptoms to measure the longitudinal course of symptoms, and (d) have concentrated mainly on men. To address these limitations, we have carried out a study of a complete cohort of new receptions into two detention centres, one holding men, and the other women, and used serial psychiatrists’ ratings of symptom severity until discharge, or up to 1 year, using a validated measure. Our aims were to (a) investigate trajectories of illness severity among male and female inmates who have mental disorders; (b) to investigate whether clinical or demographic variables are associated with different trajectories of symptom change; and (c) to investigate whether male and female inmates follow different courses with regard to the severity of mental disorder during their detention.

Methods

Setting and Population

We collected data from all inmates who were referred to the Forensic Early Intervention Service (FEIS) in two provincial correctional centres which detain remand inmates and those that have sentences of less than 2 years in Ontario: the Toronto South Detention Centre which is a facility that holds up to 1650 men, and the Vanier Centre for Women, which holds up to 300 women. We gathered data from all cases under care between September 2017 and November 2020.

Measures

At each of these institutions, all inmates were screened at reception by a nurse using the Brief Jail Mental Health Screen. 11 Those who screened positive were referred to FEIS and were assessed by a mental health practitioner using the Jail Screening Assessment Tool (JSAT). The JSAT is carried out using a 15–20 min structured interview to assess current functioning and need for mental health services, and comprises demographic, social, clinical and risk variables. 12 Following the assessment, inmates were then either discharged as not requiring the service, or were assessed to receive case management from a mental health practitioner and psychiatrist. At every clinical encounter with a psychiatrist, the severity of the mental disorder was rated using the Clinical Global Impression-Corrections (CGI-C). 13 The CGI-C is a seven-point symptom severity scale developed for use in prison settings, which ranges from 1, “No mental disorder,” to 7 “Among the most severely ill,” and has been shown to be valid within the correctional setting. 14 Ratings are based on a clinical interview, observation and collateral information, and represent global symptom severity over the previous 24 h. Analysis of serial CGI-C ratings can thus provide an objective measurement of change in symptom severity over time. All psychiatrists involved in the study received training in using the CGI-C and demonstrated high test-retest and inter-rater reliability. 15

The diagnosis was taken from the JSAT as recorded by the clinician. We categorised the diagnosis as either schizophrenia spectrum disorder/bipolar affective disorder, substance use disorder, mood disorder, or stress/anxiety disorders.

Gender was categorised as male or female. Those detained at VCW were categorised as female and those detained at TSDC were categorised as male.

Age was taken as the age at entry into the study. We created a binary age category (older/younger) split at the mean age.

Statistical Analysis

We analysed data from all inmates where the first CGI-C rating was obtained within 2 weeks of admission to the jail, and where there were 3 or more serial CGI-C ratings recorded during routine clinical encounters with a psychiatrist. We included only the first CGI-C rating where there was more than one rating on the same day. We included all CGI-C ratings until the inmate was discharged or released, up to a maximum length of observation of 365 days. We used descriptive methods and t-tests to evaluate the overall change in illness severity.

To identify trajectories of illness severity, we analysed the data using a longitudinal semiparametric method for estimating group-based mixture models using the Traj plugin in Stata 17 which is based on the SAS PROC TRAJ macro. 16 This fits semiparametric (discrete mixture) models for longitudinal data using the maximum likelihood method. This method is designed to identify distinct clusters of individuals who follow similar trajectories over time and is a specialised application of finite mixture modelling that fixes factor variance at zero. Unbalanced (variable time interval) data can be analysed, and all available data are included in the model; therefore, individuals with varying numbers of observations can be included. We specified a censored normal distribution, which is appropriate for repeated measures on approximately continuous scales with a minimum score of 1 and a maximum of 7. We specified the number of groups to be fitted between 1 and 6, and modelled the number of terms (e.g., intercept, linear, or quadratic) for each group, and rejected those that were non-significant. We made no a priori assumptions as to the number of trajectories and selected the model with the best fit using the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and other standard fit indices. We then plotted the observed mean CGI-C scores for each trajectory using TRAJPLOT in Stata. 17 The trajectory with the highest probability of membership was assigned to each participant. Trajectory group membership assignments were then used as dependent variables in multinomial logistic regression to identify clinical and demographic variables associated with group membership. In view of previous research indicating differences in mental health outcomes between males and females in correctional settings, we then carried out group-based trajectory modelling for males and females separately.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was granted by the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health Research Ethics Board (#018/2018) for this research. Participant consent was not required as it would have been impractical to obtain consent from all participants retrospectively, and the risk of any harm is low.

Results

We found 543 inmates who met inclusion criteria, 405 men and 137 women, which provided a total of 2,949 CGI-C observations. The mean number of observations per inmate was 4.3 (SD 3.6, range 3–25), with an average follow-up of 88.9 days (SD 89.3, range 3–365 days) (See Table 1). The mean length of follow-up was 96.8 days for men and 65.8 days for women (t(540) = 3.64, p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Age, Length of Observation, CGI-C Scores and Diagnostic Groups of All Inmates, and Comparisons Between Males and Females.

| Variable | All | Male | Female | t(df) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | |||||

| Age | 34.5 (11.2) | 34.4 (11.3) | 34.8 (11.1) | −0.31(540) | 0.756 |

| Length of observation | 88.9 (89.3) | 96.8 (93.3) | 65.8 (71.9) | 3.64(540) | <0.001 |

| Mean change in CGI-C score | −0.74 (1.51) | −0.62(1.5) | −1.09(0.12) | 3.27(540) | 0.001 |

| Mean initial CGI-C score | 4.02 (1.12) | 4.03(0.06) | 3.97 (0.09) | 0.58(540) | 0.563 |

| N (%) | |||||

| All | Male | Female | X2 | p | |

| Psychosis | 430 | 322 (79.5) | 107 (78.1) | 0.122 | 0.727 |

| Mood | 268 | 199 (49.1) | 69 (49.6) | 0.01 | 0.920 |

| Substance use | 269 | 212 (52.3) | 57 (41.6) | 4.72 | 0.030 |

| Concurrent disorders | 337 | 260 (64.2) | 76 (55.5) | 3.31 | 0.069 |

Note. CGI-C: Clinical Global Impressions Scale: Corrections; Df: Degrees of Freedom.

The mean age was 34.5 years (SD 11.2, range 18.4–80.7). Half of the sample (49.4%, n = 268) had a mood or anxiety disorder, 430 (79.2%) had a psychotic disorder, and 269 (52.3%) had a substance use disorder. Overall, 337 (62.1% of) inmates had two or more (concurrent) disorders; 260 (64.2%) among men and 76 (55.5%) among women, respectively. The mean difference between the first and last CGI-C score was −0.74 (SD 1.5), indicating a reduction in illness severity overall. We found that females had a greater reduction in CGI-C scores than men; −1.09 (SD 0.12) compared with −0.61(SD 0.07), t(540) = 3.27, p = 0.001 (see Table 1). The most common initial CGI-C ratings were scores of 3, 4 and 5, given to 21.9%, 19.7%, and 20.6% of the sample, respectively (see Table S2).

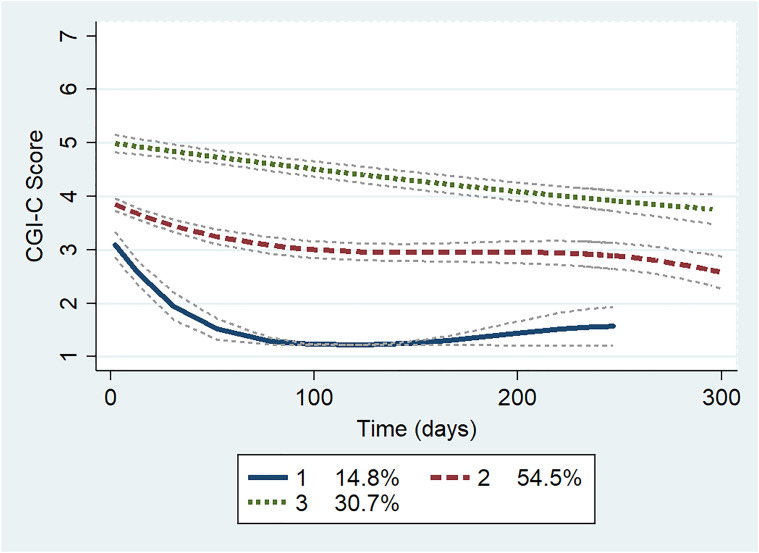

Using group-based trajectory modelling of CGI-C scores on the entire cohort, we found that 3 trajectories (2 cubic and 1 quadratic) provided the optimal solution taking into consideration parsimony and model fit indices (see Table S2). Group 1 (“Mildly ill—Resolved”) comprised 14.8% of the sample and had a mean initial CGI-C score of 3.1 (SD = 1.04), corresponding to a clinical rating of “mildly ill.” The scores in this group reduced to 1 (“no mental disorder”) over a 2–3 month period and remained between 1 and 1.5 during the remainder of follow-up. Group 2 (“Moderately ill—Improving”) was the largest group and comprised 54.5% of the sample. The mean initial CGI-C was 3.8 (SD = 0.93), and there was a gradual curvilinear decrease over the study period, ending approximately one point lower. Group 3 (“Markedly ill—Improving”) comprised 30.7% of the sample, with an initial average CGI-C score of 4.8 (SD = 0.97), and which reduced gradually in a linear trajectory, also ending one point lower (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Group-based trajectories—full cohort. CGI-C: Clinical Global Impression Scale-Corrections.

We then carried out multinomial logistic regression on the entire sample to investigate the characteristics of each group (see Table 2). We found that in comparison to the base trajectory group (Group 2: “Moderately ill—Improving”), we found that Group 1 (“Mildly ill—Resolved”) was less likely to comprise older inmates (Relative Risk Ratio (RRR) = 0.53, 95% Confidence Interval (CI) = 0.30 to 0.91) and there was weak evidence that they are more likely to have substance use disorders (RRR = 1.70, 95% CI = 0.96 to 3.04. Group 3 (“Markedly ill—Improving”) was significantly less likely to contain women (RRR = 0.39, 95% CI = 1.19 to 3.53), and this group was less likely to have substance use disorders (RRR = 0.31, 95% CI = 0.24 to 0.66).

Table 2.

Multinomial Logistic Regression Comparing Characteristics of Trajectory Groups (Groups 1 and 3 Compared with Group 2).

| Trajectory Group | Number in Group | RRR | SE | z | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 “Mildly ill—resolved” | 70 | |||||

| Female | 24 | 1.52 | 0.44 | 1.46 | 0.145 | 0.86–2.70 |

| Older | 24 | 0.53 | 0.15 | −2.29 | 0.022 | 0.30–0.91 |

| Mood | 43 | 1.46 | 0.41 | 1.37 | 0.171 | 0.84–2.54 |

| Psychosis | 49 | 0.64 | 1.97 | −1.43 | 0.152 | 0.35–1.17 |

| Substance | 47 | 1.70 | 0.50 | 1.81 | 0.070 | 0.96–3.04 |

| 2 “Moderately ill—improving” | 314 | |||||

| Female | 88 | (Base outcome) | ||||

| Older | 155 | |||||

| Mood | 155 | |||||

| Psychosis | 244 | |||||

| Substance | 314 | |||||

| 3 “Markedly ill—improving” | 159 | |||||

| Female | 25 | 0.39 | 0.07 | −5.30 | <0.001 | 0.24–0.66 |

| Older | 94 | 1.45 | 0.30 | 1.82 | 0.069 | 0.97–2.18 |

| Mood | 70 | 0.96 | 0.20 | −0.19 | 0.852 | 0.64–1.45 |

| Psychosis | 137 | 2.04 | 0.57 | 2.57 | 0.010 | 1.19–3.53 |

| Substance | 49 | 0.31 | 0.07 | −3.55 | <0.001 | 0.24–0.66 |

Note. RRR = relative risk ratio.

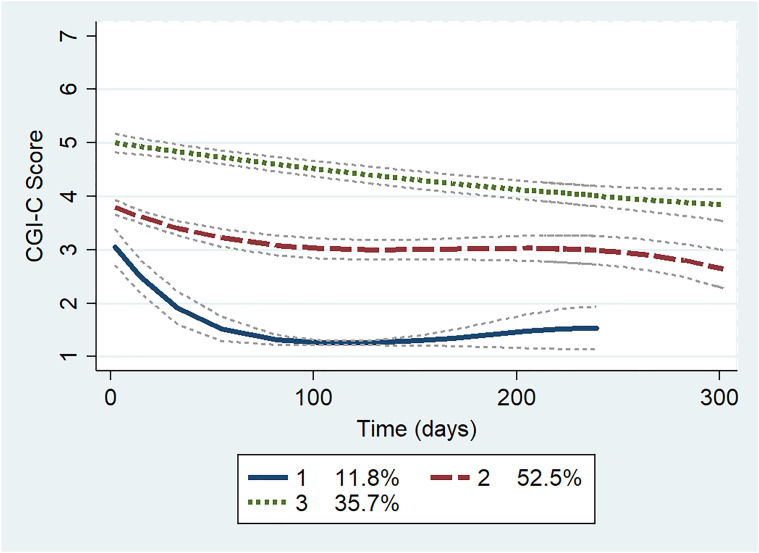

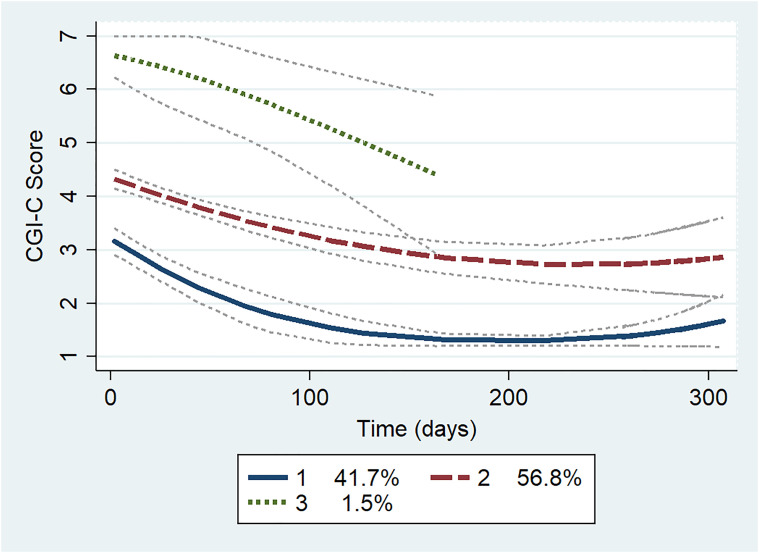

Group trajectory modelling was next carried out on males and females separately, using similar methods. The model including only males was almost identical to that which included the entire sample (see Figure 2 and Table S2) and included very similar “Markedly ill—Improving,” “Moderately ill—Improving,” and “Mildly ill—Resolved” groups. The model which included only females also yielded a three-group solution (see Figure 3 and Table S2). Group 1 comprised 41.7% of the women, and had a mean initial CGI-C score of 3.4 (SD = 1.02), which was reduced to 1–1.5 during the study period, and represents a “Mildly ill—Resolved” group. Group 2 contained 56.8% of the sample and had a mean initial CGI-C score of 4.3 (SD = 0.78) and plateaued just under 3, representing a “Moderately ill—Improving” group. Unlike in the male sample, there was a small third group comprising only 1.5% of the female sample with an initial CGI-C of 6.5 (SD = 0.71), falling to around 4.5, which we have called the “Severely ill—Improving” group.

Figure 2.

Group-based trajectories—men only. CGI-C: Clinical Global Impression Scale-Corrections.

Figure 3.

Group-based trajectories—women only. CGI-C: Clinical Global Impression Scale-Corrections.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to include all inmates with serious mental illness in a measured care pathway so as to describe the severity of illness over time. Among 543 pre-trial inmates with mental disorders with repeat measures followed for up to 1 year, we found an overall reduction in the severity of illness, with women showing slightly greater improvement than men. Approximately 15% of the entire cohort had full resolution of symptoms, whereas the remainder showed partial improvement. We identified three distinct trajectories among men and three among women, and did not identify any group that deteriorated. The largest group, comprising 54% of the sample, showed gradual improvement from a moderately to mildly ill category. Women, and those with substance use disorders, were more likely to improve and more likely to have full resolution of symptoms. When males and females were analysed separately, we found that 42% of the female group were in the “Mildly ill—Resolved” category compared with 12% of men.

Our findings are consistent with prior research findings which have shown an overall improvement in mental well-being during the initial stages of incarceration. This appears to imply that mental ill-health improves during incarceration. However, it is also possible that there is an initial deterioration in mental wellbeing at the time of incarceration due to the effects of the initial distress of incarceration, or substance use withdrawal which then improves over time. One interesting pseudo-prospective study asked inmates to rate their mental health retrospectively in the week prior to incarceration, currently, and again 5 days later, and found that inmates rated a deterioration in symptoms following incarceration that improved in as little as 5 days. 18 However, there are no prospective studies of inmates that have measured the severity of mental disorders prior to and during incarceration. True prospective studies that bridge the period of time prior to and during incarceration are very difficult to perform but are needed to investigate the impact of initial incarceration on mental health.

Although most studies have found an overall improvement, some have reported that some inmates improve and others do not. 19 For example, Baier 20 conducted a longitudinal study of Chilean prisoners who had major depressive disorder and were re-interviewed after 1 year of incarceration. They found that symptoms on average improved, but 35 out of the 79 subjects (44%) still had major depression at follow-up. 20 Inter-individual variation in prison experience as found in our study is therefore likely to be the norm, and therefore identification of sub-groups that follow similar trajectories may help in predicting outcomes and in informing treatment and service delivery.

While there may well be initial psychological distress upon entry into the detention centre, it is also likely that prison provides healthcare to the most vulnerable that was previously lacking in the community. There are high levels of homelessness, poor community healthcare, and substance use disorders among persons who become involved with the criminal justice system. 21 Once incarcerated, many inmates receive greater access to care and reduced access to street drugs, as well as more stable provision of shelter and food. All of this likely contributes to the observed improvement in symptoms during the initial stages of incarceration. It is noteworthy that all inmates in our study had a serious mental disorder, and we were therefore detecting a change in symptoms of major mental illness, rather than less severe forms of psychological distress measured in other studies.

Few studies have investigated female inmates, but there is some evidence that there may be differences in the course of symptoms between men and women. One prospective longitudinal study in the UK found that mental well-being improved among men but not in women, 9 while a study of female prisoners in Australia found high levels of psychological disturbance including anxiety and insomnia that did not decrease over time. 22

In our study, the trajectories of men and women were broadly similar and there was overall a greater reduction in symptom severity among women when compared with men. This diverges from some existing literature that showed high levels of overall symptom severity and illness comorbidities among women involved in the criminal justice system that was sustained over time.23,24 The trajectories of women with SMI in our study all showed some degree of improvement. We also identified a small group of severely ill women which represents individuals who are likely to need very intensive treatment or hospitalisation.

Although there is evidence for overall symptom improvement in both men and women, few would argue that prisons are therapeutic environments that can fully deal with the needs of inmates who are seriously unwell. The benefits of improved access to healthcare and shelter for the most vulnerable still do not represent a desirable or appropriate means of addressing the social and healthcare needs of people with SMI. In our study, less than 12% of men and 42% of women had full symptom resolution, and over one-third were still considered “Markedly ill” at the end of the study. Although all these inmates were identified as requiring treatment, some declined treatment or else did not improve with the treatments provided. In our setting, there is a limitation in access to acute inpatient treatment as often the need for acute beds outstrips the demand. 25 In addition, services aimed at promoting community reintegration are often inadequate and too often result in the gains made while in custody being lost. 21

There are a number of limitations to our study. First, we have used only a single measure for rating overall symptom severity, and would not necessarily be able to detect differences in specific forms of psychopathology. Although high test-rest and inter-rater reliability has been demonstrated among the psychiatrists who completed the ratings in this study, the possibility of errors and biases in symptom measures can not be excluded. Second, the number of groups identified was based on the best model fit, but may not represent discrete manifest entities. One of the groups in the model for female inmates was very small, and although robust to variations in specification of the model, may not be replicated in other datasets. Third, we took diagnoses from the JSAT, which is not designed to be a diagnostic tool but contains clinical diagnostic categories assigned by the clinician completing the tool. Fourth, our findings may not generalise to other settings, where prison conditions or access to healthcare are different.

Prospective measurement of symptom severity of mental disorder has rarely been carried out in remand inmates. More longitudinal studies are needed to assess changes in the severity of the mental disorder in other types of security settings and in other jurisdictions1,10 as well as changes in specific types of symptoms and disorders. Although most inmates show some improvement, and some have full resolution of symptoms, a significant number continue to have moderately severe symptoms. There is a need for adequate detection of mental disorders and appropriate treatment within the detention centre, but also the need for timely transfer to hospital for those with severe symptoms as improvement within the correctional setting tends to be modest. In addition, this study shows the advantage of building measurement into routine clinical care. This will allow objective measurement of symptom severity to inform clinical care, resource allocation, and decision-making around hospitalisation for individuals. This, in turn, can ultimately inform systems-level decision-making and policy within the correctional service with respect to treatment provision and managing inmates with significant mental health needs.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-cpa-10.1177_07067437221114095 for Change in Severity of Mental Disorder of Remand Prisoners: An Observational Group-Based Trajectory Study by Roland M. Jones, Cory Gerritsen, Margaret Maheandiran, Stephanie Penney and Alexander I.F. Simpson in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-cpa-10.1177_07067437221114095 for Change in Severity of Mental Disorder of Remand Prisoners: An Observational Group-Based Trajectory Study by Roland M. Jones, Cory Gerritsen, Margaret Maheandiran, Stephanie Penney and Alexander I.F. Simpson in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Footnotes

Authors' Contributions: RJ designed the study, carried out data analysis, and prepared the first and revised drafts of the manuscript. MM contributed to data analysis and to the preparation of the manuscript. CG, SP, and AS contributed to the design of the study and to the preparation and editing of the manuscript. All authors have read and have approved the manuscript.

Data Availability: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, RJ, upon reasonable request.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the University of Toronto (Academic Scholar Award, awarded to RJ).

ORCID iDs: Roland M. Jones https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3335-4871

Stephanie Penney https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5890-4163

Alexander I.F. Simpson https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0478-2583

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Fazel S, Hayes AJ, Bartellas K, Clerici M, Trestman R. Mental health of prisoners: prevalence, adverse outcomes, and interventions. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(9):871-881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams HK, Taylor PJ, Walker J, Plant G, Kissell A, Hammond A. Subjective experience of early imprisonment. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2013;36(3-4):241-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2015. The health of Australia's prisoners 2015. Cat. no. PHE 207. Canberra: AIHW. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baidawi S. Older prisoners: psychological distress and associations with mental health history, cognitive functioning, socio-demographic, and criminal justice factors. Int Psychogeriatr. 2016;28(3):385-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butler T, Allnutt S, Kariminia A, Cain D. Mental health status of aboriginal and non-aboriginal Australian prisoners. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;41(5):429-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edwards WT, Potter RH. Psychological distress, prisoner characteristics, and system experience in a prison population. J Correct Health Care. 2004;10(2):129-149. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Favril L, Vander Laenen F. Suicidal ideation among female inmates: a cross-sectional study. Int J Forensic Ment Health. 2019;18(2):85-98. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldberg DP. Manual of the general health questionnaire. Windsor: NFER-NELSON Publishers; 1978. p. 8-12. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hassan L, Birmingham L, Harty MA, et al. Prospective cohort study of mental health during imprisonment. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;198(1):37-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker J, Illingworth C, Canning A, et al. Changes in mental state associated with prison environments: a systematic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;129(6):427-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steadman HJ, Scott JE, Osher F, Agnese TK, Robbins PC. Validation of the brief jail mental health screen. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(7):816-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicholls TL, Roesch R, Olley MC, Ogloff JRP, Hemphill JF. Jail screening assessment tool (JSAT): Guidelines for mental health screening in jails. Burnaby, BC: Simon Fraser University, Mental Health, Law, and Policy Institute, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones RM, Moscovici M, Patel K, McMaster R, Glancy G, Simpson AIF. The Clinical Global Impression-Corrections (CGI-C). 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Jones RM, Gerritsen C, Maheandiran M, Simpson AIF. Validation of the clinical global impression-corrections scale (CGI-C) by equipercentile linking to the BPRS-E. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones RM, Patel K, Moscovici M, McMaster R, Glancy G, Simpson AIF. Adaptation of the clinical global impression for use in correctional settings: the CGI-C. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagin DS, Jones BL, Passos VL, Tremblay RE. Group-based multi-trajectory modeling. Stat Methods Med Res. 2018;27(7):2015-2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones BLN. D.S. A stata plugin for estimating group-based trajectory models. 2012. https://kilthub.cmu.edu/articles/journal_contribution/A_Stata_Plugin_for_Estimating_Group-Based_Trajectory_Models/6470963 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gibbs JJ. Symptoms of psychopathology among jail prisoners: the effects of exposure to the jail environment. Crim Justice Behav. 1987;14(3):288-310. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu SS, Sung HE, Mellow J, Koenigsmann CJ. Self-perceived health improvements among prison inmates. J Correct Health Care. 2015;21(1):59-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baier A, Fritsch R, Ignatyev Y, Priebe S, Mundt AP. The course of major depression during imprisonment - A one year cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2016;189:207-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones RM, Manetsch M, Gerritsen C, Simpson AIF. Patterns and Predictors of Reincarceration among Prisoners with Serious Mental Illness: A Cohort Study: Modèles et prédicteurs de réincarcération chez les prisonniers souffrant de maladie mentale grave : Une étude de cohorte. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2021;66(6):560-568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hurley W, Dunne MP. Psychological distress and psychiatric morbidity in women prisoners. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1991;25(4):461-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lindquist CH, Lindquist CA. Gender differences in distress: mental health consequences of environmental stress among jail inmates. Behav Sci Law. 1997;15(4):503-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown GP, Hirdes JP, Fries BE. Measuring the prevalence of current, severe symptoms of mental health problems in a Canadian correctional population: implications for delivery of mental health services for inmates. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2015;59(1):27-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones RM, Patel K, Simpson A. Assessment of need for inpatient treatment for mental disorder among female prisoners: a cross-sectional study of provincially detained women in Ontario. BMC psychiatry. 2019;19(1):98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-cpa-10.1177_07067437221114095 for Change in Severity of Mental Disorder of Remand Prisoners: An Observational Group-Based Trajectory Study by Roland M. Jones, Cory Gerritsen, Margaret Maheandiran, Stephanie Penney and Alexander I.F. Simpson in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-cpa-10.1177_07067437221114095 for Change in Severity of Mental Disorder of Remand Prisoners: An Observational Group-Based Trajectory Study by Roland M. Jones, Cory Gerritsen, Margaret Maheandiran, Stephanie Penney and Alexander I.F. Simpson in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry