Abstract

High school students in the United States are being educated during an unprecedented time of social unrest, public health concerns, and gun violence. High school student athletes can be further challenged by sports-related stressors that may lead to anxiety, burnout, depression, disordered eating, sleep difficulty, performance-based identity concerns, and substance use. High school football players, in particular, are at higher risk of concussion, musculoskeletal injury, and may feel excess pressure to compete from coaches, parents, and peers. One way to address these stressors among high school student athletes is to increase athletic department staff members’ awareness of the symptoms of mental health disorders. Increased awareness helps staff members recognize when an athlete is in crisis, as well as respond with an established mental health emergency action plan as needed. In this review article, the authors provide a blueprint by which high school personnel can more readily identify and respond to mental health emergencies among student athletes.

Keywords: crisis, emergency, high school, student athlete, football, sports, mental health

Introduction

High school students in the United States are being educated during an unprecedented time of social unrest, public health concerns, and increased gun violence within their communities and schools [1,7,9,12,17]. Students are being impacted individually and collectively by these concerning realities. Consequently, in 2021, the US Surgeon General, Vivek Murthy, issued an Advisory on Protecting Youth Mental Health, stating,

Mental health challenges in children, adolescents, and young adults are real and widespread. Even before the pandemic, an alarming number of young people struggled with feelings of helplessness, depression, and thoughts of suicide—and rates have increased over the past decade . . . the effect on their mental health has been devastating. [18]

A 2019 study found that more than 13% of children (ages 5–17 years) in the United States have been treated for a mental health–related symptom [26]. In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated mental health issues for high school students with 18% of adolescents reporting that the pandemic had a significant negative impact on their mental health [20]. After 2 years of isolation and virtual learning, 1 in 6 US adolescents (ages 12–17 years) experienced a major depressive episode, 3 million reported increased suicidal thoughts, and there was a 31% increase of mental health–related emergency room visits [22,25]. While random acts of violence, political theater, social injustices, and the impact of the ongoing global pandemic remain, adolescents are often ill equipped to deal with these intense external challenges and manage their internal experiences and feelings of stress. Unfortunately, across the United States, secondary schools lack adequate mental health resources.

According to the American School Counselor Association (ASCA), 47 states remain above their recommended ratio of counselors per student (250:1), with only New Hampshire (208:1) and Vermont (186:1) reporting ratios within the recommendation [3]. In addition, data show that students of color and students from low-income families typically have less access to school counselors, despite being more likely to name their school counselor as helpful with future planning [6]. High school student athletes are represented in the statistics; however, they are further challenged by having to manage different external stressors than their nonsport peers.

Just less than 1 million high school boys play 11-player football, with girls increasingly participating [14]. High school football, in particular, poses risk of concussion, musculoskeletal injury, and excess pressures to compete from coaches, parents, and peers [4,10,24]. Sport-related stressors can result in increased mental health–related symptoms such as anxiety, burnout, depression, disordered eating, difficulty with sleep, performance-based identity concerns, managing injury, substance use, and more. While physical activity has repeatedly demonstrated benefits in protecting against mental illness [20], some norms in athletic culture can discourage help-seeking behavior, increase mental health stigma, and limit opportunities to address mental health issues [24].

The combination of high external stressors, high internal pressure to perform, mixed with limited mental health resources, and a culture that devalues help-seeking behavior, can increase a teenager’s risk of a mental health crisis. Many articles have proposed the benefits of medical emergency action plans in secondary education; however, little research has been conducted on the development and execution of such action plans in high school athletic departments. Increasing athletic department staff members’ ability to understand the symptoms of mental health disorders, to recognize when an athlete is in crisis, and to develop a mental health emergency action plan are ways to address mental health issues among high school student athletes.

This article aims to provide high school personnel a blueprint by which to identify and respond to student athlete mental health emergencies.

Defining Mental Health Disorders

The American Psychological Association (APA) defines a mental health disorder as “any condition characterized by cognitive and emotional disturbances, abnormal behaviors, impaired functioning, or the combination of these symptoms” [2]. Such disorders are affected by many factors and cannot be accounted for by solely environmental circumstances, whether physical, chemical, or social. There has been little research done on mental illness among high school football players, although numerous studies have been conducted on adult players; for example, a 2020 study found that former professional American football players who reported daily cognitive problems had increased odds of having symptoms of depression and anxiety than did players who reported no cognitive issues [19].

High school administrators, athletic trainers, school counselors, school nurses, coaches, and other personnel who have regular contact with high school student athletes should be familiar with the psychological, cultural, and environmental factors that affect adolescent mental health and the following mental health disorders affecting high school student athletes [2,13].

Anxiety is an emotion that causes both physical and cognitive disturbances. Cognitive symptoms include intrusive thoughts, rumination, and worry. Physical symptoms such as high blood pressure, trembling, rapid heartbeat, sweating, dry mouth, and dizziness can also occur.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is characterized by persistent behavioral disturbances that make daily focus challenging. Symptoms of attention deficits include difficulties in maintaining focus, organizing, and adapting to changes in routine. Symptoms of hyperactivity include being fidgety, impulsive behavior, and speaking out of turn.

Depression is a mood disorder that causes extreme sadness or despair. This emotional state interferes with the daily functioning and can cause weight loss or gain, fatigue, feelings of worthlessness, inappropriate guilt, difficulty thinking, and depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day. Diagnosis requires that these symptoms are present for at least 2 weeks.

Disordered eating involves persistent distressing thoughts and emotions that affect behavior around eating. Common eating disorders include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder. Each disorder can negatively affect daily physical, psychological, and social functioning.

Trauma is an extremely stressful event that is marked by a sense of horror, helplessness, serious injury, or the threat of serious injury or death. Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder may arise 1 month to multiple years after an event. These symptoms include intrusive memories of the event; avoidance of places, activities, or people reminiscent of the event; increased negative thinking and mood; physical or emotional changes such as insomnia, difficulty concentrating, irritability, overwhelming guilt, or being easily startled.

Substance use disorder involves excessive use of alcohol, tobacco, opioids, caffeine, cannabis, hallucinogens, inhalants, sedatives, hypnotics, anxiolytics, amphetamine, cocaine, other stimulants, and more. Disordered use can be defined as mild, moderate, or severe.

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder occurs in children ages 18 years or younger with persistent irritability and an average of at least 3 episodes per week of extreme behavioral dysregulation. It is an alternative to the diagnosis of bipolar disorder in children.

Mood disorder presents as “prolonged, pervasive emotional disturbance” [2] that can include bipolar disorder, depressive disorder, substance-induced mood disorder, and mood disorders due to a general medical condition.

Suicidal ideation involves a preoccupation with killing oneself, often as a symptom of major depression [2].

Psychosis is an abnormal mental state that disrupts perception, cognition, emotions, and affect; these impairments often manifest in delusions, hallucinations, and significantly disorganized speech.

Deliberate self-harm is the intentional, direct destruction of body tissue most commonly by cutting, burning, scratching, self-hitting, self-biting, and head banging. While intent to die is not its main motivator, it can nonetheless potentially life-threatening.

During this critical time of adolescence, student athletes are vulnerable to situations that may minimize their confidence or reinforce a negative self-image; this is also the period of development in which the onset of mental health symptoms may occur [21]. School officials and coaches should all foster an athletic environment that is safe, inclusive, and free from bullying, hazing, and overt punishment. Furthermore, administrators, teachers, staff, and coaches must prioritize environments where acceptance and respect of one another are encouraged. By creating nurturing academic and athletic spaces, stigma surrounding mental health conditions can be reduced and student athlete’s willingness to seek help can increase [11]. High school personnel also need to be mindful that stressors from athletics, academics, and family or social situations can diminish a student’s ability to cope with adversity. Preventative care, early detection, and intervention alone may not improve student athletes’ stresses, and such efforts may overwhelm staff and coaches. If this occurs, they may need to consider asking for support from the parents, health professionals, and/or local community services such as youth programs and crisis centers.

Identifying a Mental Health Crisis

A mental health crisis involves an acute disturbance that puts the safety of the student athlete or others (eg, teammates/coaches) at risk or renders the student incapable of self-care. Mental health issues can occur anytime—during school hours, at practice or games, or while traveling. Unfortunately, due to these varied hours and locations, it can become unclear who should serve as the point person during a high school athletic mental health emergency. Most high schools do not employ a clinically trained sport psychologist and administrators (eg, athletic director, principal) do not always attend practices and games. With limited mental health resources in schools, school administrators, school nurses, cafeteria staff, school security, teachers, coaches, and athletic training, staff must understand the warning signs of a mental health crisis and what actions to take to support the student in crisis. The National Alliance on Mental Illness [14] has detailed the common signs of a mental health crisis, including the following.

Inability to perform daily tasks includes difficulty with bathing, brushing teeth, dressing, eating/preparing meals, going to school, or attending practice/other obligations.

Rapid mood swings may involve feelings of happiness and sadness, increased energy levels, inability to stay still, pacing, sudden depression, withdrawal, becoming suddenly happy or calm after a period of depression.

Increased agitation may involve disruptive or impulsive behavior, irritability, verbal threats, violently out of control, destroying property, outbursts.

Abusive behavior includes deliberate violence, which may include punching, kicking, biting, choking, burning, shaking, beating, self-harm, substance use, physical abuse, emotional abuse.

Isolation includes a voluntary lack of contact with others while at school or at home.

Being out of touch with reality involves an inability to recognize family or friends, signs of confusion, strange ideas, thinking they are someone they are not, not understanding what people are saying, hearing voices, seeing things that are not there.

Paranoia involves intense anxious or fearful feelings and thoughts often related to persecution, threat, or conspiracy, mistrust of people or their actions without evidence or justification.

Other warning signs in adolescents may include eating or sleeping too much, having low energy, complaining of unexplained stomachaches or headaches, feeling helpless or hopeless, smoking or drinking or using drugs (including prescription medications), worrying, not adjusting to home or school life [23].

Suicide warning signs can also be symptoms of depression. If a student athlete expresses thoughts of suicide, it should be taken seriously [5]. For example, saying things like “Nothing matters anymore,” “You will be better off without me,” or “Life isn’t worth living.” The following behaviors may also indicate suicidal thinking:

Talking as if they are saying goodbye or going away forever;

Taking steps to tie up loose ends, like giving away possessions;

Stockpiling pills or obtaining a weapon;

Preoccupation with death;

Sudden cheerfulness or calm after a period of despondency;

Dramatic changes in personality, mood, and/or behavior;

Increased drug or alcohol use;

Withdrawal from friends, family, and normal activities;

Failed romantic relationship;

Sense of utter hopelessness and helplessness;

History of suicide attempts or other self-harming behaviors;

History of family/friend suicide or attempts.

Other considerations for suicide warnings among youth include [5] the following:

Current mental disorder including affective disorder, mood disorder, substance abuse, personality disorder, eating disorder (eg, anorexia nervosa);

Personality characteristics that include ridged thinking, inability to problem solve, poor mood regulation, and impulsive behavior;

Family conflict;

Contagion-Imitation—the imitation of suicide behavior being evoked at both macro (eg, news media) and micro (eg, peer group) level.

Preventative measures can keep an overwhelming situation from escalating into an emergency. School personnel can help student athletes feel calm, protected, and heard and thereby stabilize the situation by engaging in techniques that reduce strong emotions until additional help arrives (Table 1) [14].

Table 1.

Techniques that may help de-escalate a crisis.

| What to do: | ||

|---|---|---|

| Keep your voice calm | Avoid overreacting | Listen to the person |

| Express support and concern | Avoid continuous eye contact | Ask how you can help |

| Keep stimulation level low | Move slowly | Be patient and give them space |

| Offer options instead of trying to take control | Avoid touching the person unless you ask permission | Gently announce actions before initiating them |

| What not to do: | ||

| Make judgmental comments | Argue or try to reason with the person | Make them feel trapped |

Adapted from National Alliance on Mental Illness [14].

When to Activate a Mental Health Emergency Action Plan

Both internal and external stressors can lead to crises, and so understanding the student athlete’s home, school, athletic, and work environments may provide context to their experience. However, when a student athlete’s life is in immediate danger the mental health emergency action plan is initiated. Such situations include, but are not limited to, the following [15]:

Suicidal and/or homicidal ideation;

Sexual assault;

Agitation or threatening behavior;

Acute psychosis or paranoia;

Acute delirium/confused state;

Acute intoxication or drug overdoes;

Uncharacteristically aggressive behavior;

Unexplained absence/Missing from building.

A mental health emergency action plan establishes a standard response to mental health crises, which can occur in various environments and situations. When developing this plan, several steps must be taken to ensure the safety of the student athlete. A crisis team will create and execute the plan. The team should consist of key school personnel who are responsible for student athletes’ mental, physical, and emotional health. Examples of school personnel might include the school principal, athletic director or trainer, counselor, nurse, school law enforcement, or the head coach.

Because most high school student athletes are minors, activation of the plan may involve parents and/or legal guardians. Prior to developing a mental health emergency action plan for high school student athletes, federal, state, local laws, and school regulations must be considered [8]. This is to ensure the privacy laws connected to mental health information of minors are not violated, while also balancing parental rights and the proper notification of a mental health emergency to parents, guardians, or emergency contacts. In addition, identifying local resources is paramount to ensure additional support mechanisms are in place so that once the crisis has been managed, the transfer to ongoing care occurs smoothly.

According to the National Collegiate Athletic Association’s Mental Health Best Practices [15], a mental health emergency action management plan should encompass 9 major parts (Table 2). These best practices have been adapted to consider the unique aspects of working with high school populations. First, the plan should define which situations, symptoms, or behaviors that would be considered a mental health emergency. Procedures must be written on how to manage specific mental health emergencies, including a student athlete who expresses suicidal or homicidal ideation, is losing touch with reality, experiences a recent death, and/or becomes a missing person. The plan should identify the situations that could result in the immediate contact of law enforcement, emergency medical services, and school administration. Next, if there is a need for an acute crisis intervention, and a student athlete needs to be hospitalized, a predetermined list of local involuntary retention locations must be made available. During this time, it is imperative to identify a licensed mental health counselor on-school grounds, or a community-licensed mental health counselor off-school grounds. This person can provide in-person support or help intervene and stabilize the situation. In certain circumstances, the primary care physician serving as the team doctor may fulfill this role. For stakeholders (eg, coaches, athletic trainers) that are involved, a clear role in managing the mental health crisis needs to be established. This may involve creating a private environment or managing groups of people who are not involved in the event. After the crisis has resolved, specific steps can be established to provide resources to the student athlete. Emergency procedures should be reviewed and updated after the conclusions of a crisis situation. Finally, a formal policy that incorporates federal, state and local laws, and school regulations on parental and guardian involvement during a mental health emergency must be researched and reviewed by members of the crisis team. Table 2 provides a checklist to help guide the building of the Mental Health Emergency Action Plan with all necessary components.

Table 2.

Checklist for mental health emergency action management plan (MHEAMP).

| ▭ | Situations, symptoms, or behaviors that are considered mental health emergencies. |

| ▭ | Written procedures for management of the following mental health emergencies: • Suicidal and/or homicidal ideation • Sexual assault • Highly agitated or threatening behavior, acute psychosis, or paranoia • Acute delirium/confused state • Acute intoxication or drug overdose • Missing from building/Unexplained absence |

| ▭ | Situations in which the individual responding to the crisis should immediately contact emergency medical services (EMS), school administration, and law enforcement. |

| ▭ | Individuals responding to the acute crisis should be familiar with the local municipality protocol for involuntary retention, eg, if the student athlete is at risk of self-harm or harm to others. |

| ▭ | Situations in which the individual responding to the crisis should contact a trained on-call counselor who will be able to provide direct and consultative crisis intervention to the student athlete in need. In addition, help stabilize the situation and recommend next steps for action. May need to consider community personnel, including a crisis center designated to address sexual assault. |

| ▭ | The management expectations of each stakeholder within athletics during a crisis (eg, coach, sports medicine personnel). |

| ▭ | Specific steps to be taken after an emergency have resolved to support the student athlete who has experienced the mental health emergency by providing appropriate resources and follow-up care through school counselor. |

| ▭ | A procedure for reviewing preventative and emergency procedures after the resolution of the emergency. |

| ▭ | A formal policy for when family members will be contacted in the event of a mental health emergency (in accordance with federal, state, local laws, and school regulations). |

Adapted from National Collegiate Athletic Association Mental Health Best Practices [15].

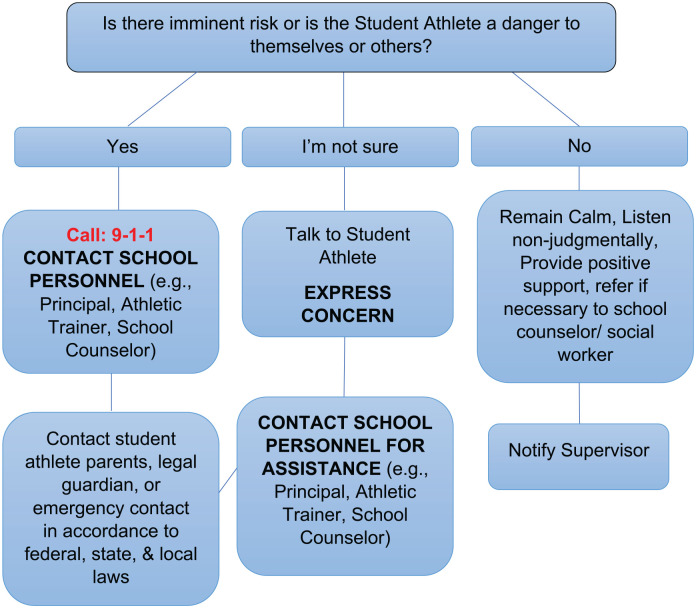

The example flow chart in Fig. 1 could be included in the written procedures for how to manage specific mental health emergencies. It is intended to assist principals, athletic directors, athletic trainers, school counselors, and other school employees when responding to a student athlete in distress. It is important to understand if the student athlete is in imminent danger to themselves or others, the steps the crisis team would follow is different than if the situation is less severe. High school athletic departments should defer to their licensed mental health personnel or medical provider to determine best course of action. When possible, student athletes who are experiencing a mental health emergency should be referred to local resources that have an established relationship with their school. In the event, that the student athlete experiences a mental health emergency while traveling with their team, the school should coordinate with the visiting team on local area resources.

Fig. 1.

Mental health emergency flow chart (example).

Once all the elements of the checklist have been decided and documented, it is critical that the crisis team reviews and rehearses the execution of the plan for a variety of scenarios. It is also recommended that the plan is reviewed once or twice a year to ensure that any updates from previous crises or personnel changes have been made.

Summary

A recent survey estimated that a little more than 1 million US students participate in high school athletics [16]. Today’s high school student athletes experience unique external and internal pressures compared with the general student body. More needs to be done to help staff, coaches, and administrators to support the mental health of student athletes. Preventive measures must be the first line of defense. It is imperative to create a culture that encourages help-seeking behavior, does not stigmatize mental health, and encourages communication and coping skill development. In addition, it is critical to build a mental health emergency action plan that identifies problematic behavior and the steps needed to support student athletes in crisis. The Mental Health Emergency Action Plan should provide a robust list of local and community resources for both student athletes and administrators to access for support during and after emergencies. A list of national resources that provide mental health support can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Available resources.

|

NAMI (National Alliance on Mental Illness) 1-800-950-6264 https://www.nami.org |

Crisis Text Line Text MHFA to 741741 for free 24/7 crisis counseling |

|

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 1-800-662-HELP (4357) https://www.samhsa.gov |

Lifeline Crisis Chat Visit

www.crisischat.org/ |

|

National Eating Disorders Association 1-800-931-2237 https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org |

Supporting Child and Student Social, Emotional, Behavioral, and Mental Health Needs www.ed.gov (Dept. of Education) |

|

Trevor Lifeline (LGBTQ+)* 1-866-488-7386 http://www.thetrevorproject.org |

National Center for School Mental Health: Resources to promote a positive school climate

https://safesupportivelearning.ed.gov/ |

|

Samaritan Confidential Hotline 1-212-673-3000 https://samaritanshope.org/our-services/24-7-helpline/ |

Mental Health Technology Transfer Center Network: https://mhttcnetwork.org/—School mental health resources |

|

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (24/7) 9-8-8 1.800.273.TALK (8255) 1.888.628.9454 for assistance in Spanish www.suicidepreventionlifeline.org |

StopBullying.gov

https://www.stopbullying.gov/ |

Adapted from Elkins and Johnson [9].

LGBTQ+ is defined as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, or questioning and others.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-hss-10.1177_15563316221141884 for Considerations for Developing a Mental Health Emergency Action Plan for High School Football Programs and Athletic Departments by Nohelani M. Lawrence and Kensa Gunter in HSS Journal®: The Musculoskeletal Journal of Hospital for Special Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-hss-10.1177_15563316221141884 for Considerations for Developing a Mental Health Emergency Action Plan for High School Football Programs and Athletic Departments by Nohelani M. Lawrence and Kensa Gunter in HSS Journal®: The Musculoskeletal Journal of Hospital for Special Surgery

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was not required for this review article.

Required Author Forms: Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the online version of this article as supplemental material.

ORCID iD: Nohelani M. Lawrence  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1770-2298

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1770-2298

References

- 1.Abdallah HO, Zhao C, Kaufman E, et al. Increased firearm injury during the COVID-19 pandemic: a hidden urban burden. J Am Coll Surg. 2021;232(2):159–168.e3. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychological Association. APA dictionary of psychology. Date unknown. Available at: https://dictionary.apa.org. Accessed August 20, 2022.

- 3.American School Counselor Association. Student to school counselor ratio 2020-2021. Date unknown. Available at: https://schoolcounselor.org/getmedia/238f136e-ec52-4bf2-94b6-f24c39447022/Ratios-20-21-Alpha.pdf. Accessed August 20, 2022.

- 4.Baker C, Browning S, Charnigo R, et al. Factors related to return to play after knee injury in high school football athletes. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28(9):629–634.e1. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bilsen J. Suicide and youth: risk factors. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:540. 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cholewa B, Burkhardt CK, Hull MF. Are school counselors impacting underrepresented students’ thinking about postsecondary education? A nationally representative study. Prof Sch Couns. 2015;19(1):144–154. 10.5330/1096-2409-19.1.144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cimolai V, Schmitz J, Sood AB. Effects of mass shootings on the mental health of children and adolescents. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2021;23(3):12. 10.1007/s11920-021-01222-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elkins G, Johnson J. Mental health emergency action plan necessity for schools. National Federation of State High Schools. Available at: https://www.nfhs.org/articles/mental-health-emergency-action-plan-necessity-for-schools/. Published April12, 2022. Accessed August 22, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galea S, Abdalla SM. Covid-19 pandemic, unemployment, and civil unrest. JAMA. 2020;324(3):227–228. 10.1001/jama.2020.11132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gessel LM, Fields SK, Collins CL, et al. Concussions among United States high school and collegiate athletes. J Athl Train. 2007;42(4):495–503. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Christensen H. Barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking for young elite athletes: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12(1):157. 10.1186/1471-244x-12-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee J. Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(6):421. 10.1016/s2352-4642(20)30109-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mayo Clinic. Mental illness in children: know the signs. Date unknown. Available at: https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/childrens-health/in-depth/mental-illness-in-children/art-20046577. Accessed August 20, 2022.

- 14.National Alliance on Mental Illness. Navigating a mental health crisis. Available at: https://www.nami.org/Support-Education/Publications-Reports/Guides/Navigating-a-Mental-Health-Crisis/Navigating-A-Mental-Health-Crisis. Published 2018. Accessed August 20, 2022.

- 15.National Collegiate Athletic Association Sport Science Institute. Inter-association consensus document: best practices for understanding and supporting student athlete mental wellness. Available at: https://www.ncaa.org/sports/2016/5/2/mental-health-best-practices.aspx. Published 2020. Accessed August 20, 2022.

- 16.National Federation of State High School Associations. 2018-2019 high school athletics participation survey. Available at: https://www.nfhs.org/media/1020412/2018-19_participation_survey.pdf. Published August28, 2019. Accessed August 20, 2022.

- 17.Office of the Surgeon General. Protecting youth mental health: the US Surgeon General’s advisory. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-youth-mental-health-advisory.pdf. Published 2021. Accessed August 20, 2022.

- 18.Office of the Surgeon General. U.S. Surgeon General issues advisory on youth mental health crisis further exposed by COVID-19 pandemic. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2021/12/07/us-surgeon-general-issues-advisory-on-youth-mental-health-crisis-further-exposed-by-covid-19-pandemic.html. Published December7, 2021. Accessed August 20, 2022.

- 19.Plessow F, Pascual-Leone A, McCracken CM, et al. Self-reported cognitive function and mental health diagnoses among former professional American-style football players. J Neurotrauma. 2020;37(8):1021–1028. 10.1089/neu.2019.6661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schuch FB, Vancampfort D, Firth J, et al. Physical activity and incident depression: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(7):631–648. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17111194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solmi M, Radua J, Olivola M, et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;27(1):281–295. 10.1038/s41380-021-01161-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP21-07-01-003, NSDUH Series H-56). Date unknown. Available at: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt35325/NSDUHFFRPDFWHTMLFiles2020/2020NSDUHFFR1PDFW102121.pdf. Accessed August 20, 2022.

- 23.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Warning signs and risk factors for emotional distress. Available at: https://www.samhsa.gov/find-help/disaster-distress-helpline/warning-signs-risk-factors. Published May16, 2022. Accessed August 20, 2022.

- 24.Wilkerson TA, Stokowski S, Fridley A, Dittmore SW, Bell CA. Black football student athletes’ perceived barriers to seeking mental health services. J Issues Intercoll Athl. 2020;13(2):55–81. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yard E, Radhakrishnan L, Ballesteros MF, et al. Emergency department visits for suspected suicide attempts among persons aged 12–25 years before and during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, January 2019–May 2021. MMWR. 2021;70(24):888–894. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7024e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zablotsky B, Terlizzi EP. Mental health treatment among children aged 5-17 years: United States 2019. National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief, No 381. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db381.htm?msclkid=fec679a9b2ac11eca63a247935331717. Published September2020. Accessed August 20, 2022. [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-hss-10.1177_15563316221141884 for Considerations for Developing a Mental Health Emergency Action Plan for High School Football Programs and Athletic Departments by Nohelani M. Lawrence and Kensa Gunter in HSS Journal®: The Musculoskeletal Journal of Hospital for Special Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-hss-10.1177_15563316221141884 for Considerations for Developing a Mental Health Emergency Action Plan for High School Football Programs and Athletic Departments by Nohelani M. Lawrence and Kensa Gunter in HSS Journal®: The Musculoskeletal Journal of Hospital for Special Surgery