Introduction: What’s Different on the Sidelines?

The sidelines during a football game can seem like a foreign place to care for injured patients. In an office or clinic, the patient has made an appointment to see you, and that patient is your sole focus. On the sidelines, though, you are secondary to the game. The primary focus is on the players’ and team’s intent to succeed, no matter the level, from high school to professional. Knowing your place, you can display a professional deference to the course of the game and train a physician’s eye on nearly every down for signs of trouble. Watch the players as they emerge from a play or as they come off the field during a change of possession. Are any of them cradling a hand or wrist, not moving an elbow? Scan the bench area, as well.

Lower-extremity injuries are generally more apparent; a limp is seen by all. Injuries to the digits, wrist, forearm, and elbow are sometimes slow to emerge or actively concealed. Some players may not want to come forward immediately; some simply chalk it up to a sprain. I have known 3 players who continued to play several downs and even cover a kickoff with a displaced fracture of the forearm.

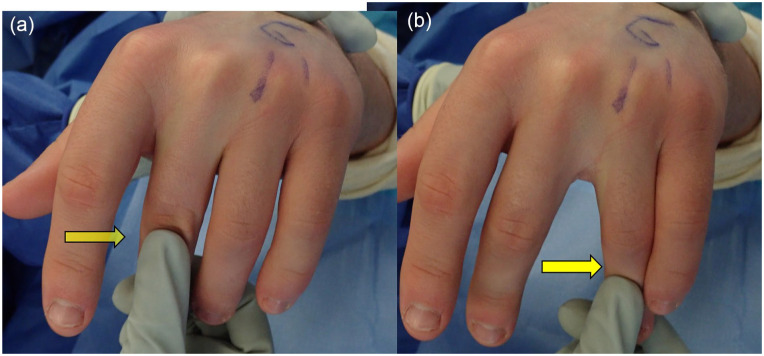

When an injured player is identified, the training staff are usually the first to assess. With years of experience, they can triage and treat many conditions. Don’t rush to “take charge.” Rather, let others examine the player, but be prepared to intervene. There is no substitute for performing your own history and examination. Be aware, too, that the player may be upset at the prospect of being taken out of the game or of a career-ending injury. An emotional flurry may temporarily interfere with initial assessment. As things calm down, triage the severity and determine whether the player can go right back in, needs to be pulled out to allow for a more complete examination with imaging, or should come out of the game based on a suspicious, and worrisome, deformity (Fig. 1a, b).

Fig. 1.

(a) Rotational deformity can be subtle but telling. This player had little pain, despite the displaced fracture ultimately seen on X-ray (b).

It is always best to err on the side of caution to protect the player’s short- and long-term interests.

Common Injuries and Trends to Consider

The upper-limb injuries seen in football players have not changed dramatically in location or severity [1,6]. Injuries to the thumb and digits are common with tackling, ball handling (both receiving and contesting the catch), digits caught in jerseys, or simply in the scrum. Many players are not certain what exactly happened because of the speed and intensity of the game.

If the general categories and locations of injury have changed little in the past 30 years, our understanding continues to improve because of better imaging and closer scrutiny during follow-up. The intensity of care has also increased, as players seek optimal care for career longevity and life after football. Subspecialization of hand injuries, once rare in acute care management, has become commonplace and with that, the body of knowledge and insight has grown.

What has also substantively changed is the quality of imaging, both computed tomography (CT) scanning and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The resolution of both modes is higher, and multiplanar reconstruction permits a 3-dimensional conceptual enhancement. With contemporary MRI, visualizing ligaments, cartilage, tendons, vessels, and nerves out to the tip of the finger is routine [3]. The evidence of acute injury as seen on short-tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequences can distinguish old injury from recent.

On the treatment side, a wider range of implants for enhancing fracture fixation and soft-tissue repair and reconstruction has improved overall care, but the number and variety of new products introduced each year can be challenging to keep up with. The field of orthobiologics is also rapidly expanding.

A note on using Google image search and emerging knowledge acquisition: The value and impact of ubiquitous, immediately available cloud-based information regarding specific injuries cannot be measured. Traditional, multiedition texts, such as Green’s Operative Hand Surgery [7], continue to be a valued resource, but Google cannot be ignored. From a simple search, you can view an expanse of remarkably instructive images, conceptual drawings, and videos clips that depict clinical cases. The inevitable inaccuracy of a text-based search, without dropping into the “word-sense disambiguation” hole, is a tolerable trade-off. As an exercise, I recommend searching for the types of injuries described below and do a bit of grazing in each to familiarize yourself with the appearance of these injuries and the proffered mechanisms of injury and treatment. The acute management recommendations are usually supplemented by illustrations. Some of the visual concepts depicted, especially in surgical management, can be dated, but then so are the books on our shelves.

Having a working knowledge of the following conditions can help before you step onto the field.

Injuries to the Thumb

Injuries to the thumb at all player positions are common. Collateral ligament tears at the metacarpophalangeal (MP) joint, fractures of the metacarpal shaft, and fractures with dislocations of the carpometacarpal (CMC) joint (Bennett’s Fracture) are also common [4].

Collateral Ligament Tears of the MP Joint

The so-called gamekeeper’s or skier’s thumb is quite different in football than in other settings. In football, the impact force is greater, and up to 1/3 of injuries disrupt both the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) and radial collateral ligament (RCL) [2] (Fig. 2a-c). The dorsal capsule is also torn and this feature of the injury may be under-appreciated (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

(a) MR images demonstrate ligament disruption of both the UCL and RCL. (b) The dorsal capsule is detached with subsequent volar subluxation of proximal phalanx. (c) Dramatic instability is seen when both ligaments are completely avulsed. UCL ulnar collateral ligament, RCL radial collateral ligament.

Time of discovery

Immediate: common, but not universal

After the game, days later, or even months later: very common

History (questions to ask)

Was the thumb injured in the past? This question may elicit a response such as “I may have sprained this 2 years ago.”

Examination

- Degree of swelling

- Minimal: Suspect a previous injury if there is notable instability but little swelling.

- Moderate with ecchymosis: Suspect a combination injury, involving ligaments and fracture.

- Crepitation: Suspect fracture and ligament tear.

- Check dorsal capsule laxity by checking radial deviation with MP joint in extension then in 30° flexion.

- Check for possible RCL tenderness or laxity as well.

- Examine the other thumb (if it has not been injured)

- The degree of ligamentous laxity in human MP joints is quite variable, but if the opposite thumb is uninjured, asymmetry can be telling.

Immediate management

Safest: Remove player from the game and splint for postgame assessment and imaging.

For those with minimal swelling or tenderness and history of prior injury: Tape and return to play after sideline assessment of strength and ability to grab and catch.

In-season management of UCL and/or RCL tears

For high school players, the usual treatment is to proceed with surgery and protect the repair with a sturdy splint/cast; 6 weeks of healing time is required. Return to play before that time requires a sturdy splint/cast to protect the repair. The rules regarding playing with casts vary by region. When in doubt, keep them out.

For college-level and professional players, deferring definitive repair is an option with no discernable risk, provided that the treating physician is knowledgeable. A graft is not required with delayed repair. The presence of a Stener lesion has caused some to believe that surgery is both inevitable and urgently needed. For players who cannot play with a splint or cast, delaying surgery allows continued play without lessening the chance of success [6]. In nonathletes, especially older patients, a Stener lesion lessens the likelihood of a stable thumb without surgery and with little benefit to waiting.

The technical goal is restoration of stability and correction of the volar subluxation (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Repair of the radial and ulnar collateral ligaments, with inclusion of the dorsal capsule in the repair.

Future concerns and risks

Because the incidence of these injuries is high, repeat tears, even years after a successful repair, can happen. One player had 3 separate injuries to his thumb. By the third injury, the combination of cartilage wear at the joint and soft-tissue attenuation led to choosing an MP joint arthrodesis, which was well tolerated. He continued to play (in the starting lineup) 2 more seasons as an offensive lineman, including at the center position, without impairment.

Fracture and Dislocation at the Base of the Thumb: Bennett’s Fracture

Time of discovery

Immediate: this high-energy injury is quite painful with movement of thumb and wrist.

History (questions to ask)

Are there any other areas on the same hand or wrist that are painful?

Exam

Degree of swelling is moderate if joint is minimally displaced.

With dislocation of the CMC joint, swelling is magnified (Fig. 4a).

Any passive manipulation of the joint will cause crepitation and can be quite painful.

Fig. 4.

(a, b) Bennett’s fracture in a defensive back before and after open reduction with compression screws to maintain reduction.

Immediate management

Remove player from the game for imaging and splint for comfort.

In season management of base of thumb injuries

Most of these injuries require prompt operative stabilization and protective splinting for 6 to 8 weeks (Fig. 4b).

Future concerns and risks

Achieving a stable thumb in a reduced position is crucial. The techniques for achieving this are beyond the scope of this writing, but it is worth mentioning that the joint must be secured in the reduced position during healing. The position of the fracture fragment itself is of less importance.

Injury to the Digits (Not the Thumb)

These injuries include MP joint injury and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint dislocations (dorsal and volar).

MP Joint Injury

Collateral ligament injuries at the MP level are quite common and less obvious than those of the thumb. The RCL is usually injured as the “jammed finger” is caught or loaded, and the MP joint is strained in an ulnar deviation direction. It is helpful to remember that these ligaments are lax when the joint is fully extended but tight in flexion. The injury can occur in the adjacent fingers. All digits should be examined.

Time of discovery

This injury is often discovered well after the initial contact. The player often ignores the pain, as the MP joint knuckle can be sore from the frequent collisions involved in tackling. As with the thumb, operative repair can be safely postponed.

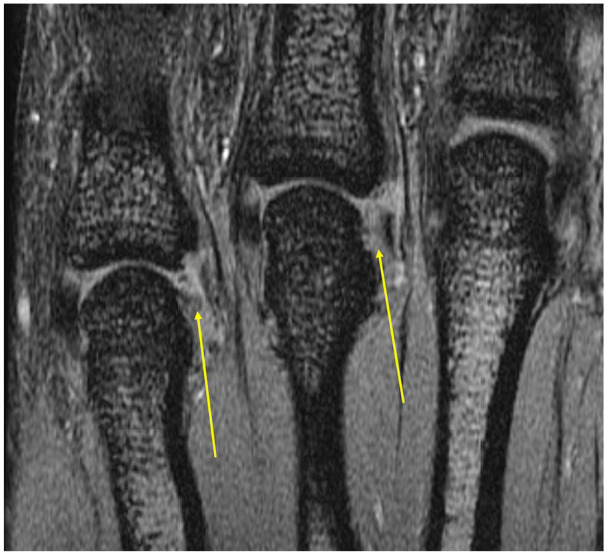

Exam

Palpate the sides of the MP joint and the dorsal surface, ruling out a possible fracture. The retracted ligament off the proximal phalanx can sometimes be palpated before swelling occurs. First, stress an uninjured adjacent digit by gently checking the resistance to ulnar–radial deviation with the joint extended and then flexed at 90° (Fig. 5a, b). Then perform the same sequence of maneuvers on the injured digit. The asymmetry is usually striking. If there is any crepitation, a fracture should be suspected. Imaging with MRI is usually diagnostic (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

(a, b) Ring finger RCL is torn, showing ulnar deviation in a flexed position. By comparison, the long finger is stable to ulnar stress. RCL radial collateral ligament.

Fig. 6.

Complete disruption of the RCL of 4th and 5th, consistent with exam. RCL radial collateral ligament.

Immediate management

If a fracture is suspected, the player should come out of the game until imaging can be obtained.

If the joint is tender but stable, continued play becomes a judgment call having to do with the age and stage of the player. If high school or younger, it is reasonable to pull the player for a complete assessment. For older players, buddy-taping may suffice and allow return to play.

If the joint is unstable and swollen, apply ice and elevate. Pain and tenderness often preclude immediate return to play, even with taping. Re-examine the player after 15 to 20 minutes of ice and elevation. If the player can make a fist, tolerate impact to the area, and perform maneuvers such as catching the football, a return to the field could be considered with buddy-taping.

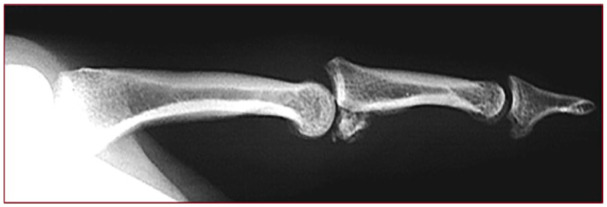

PIP Joint Dislocations (Dorsal)

Perhaps the most common hand injury in the game, especially at the college and professional level [5], PIP joint dislocations are often managed acutely by the patient, by yanking the injured digit back into place. Although training staff are usually familiar with these injuries, a complete assessment is needed to optimize outcomes. A fracture of the volar lip of the proximal phalanx may herald an unstable joint, requiring surgery (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

After dorsal PIP joint dislocation, this did not stay reduced. As suspected, a volar lip fracture was present that required surgical stabilization. PIP proximal interphalangeal.

Time of discovery

Usually immediate, especially if it is the first occurrence.

If not, the first time, the discovery may be delayed because of player reticence.

Immediate management

- If first time, an X-ray is needed to look for fracture.

- If no fracture, splint the PIP joint in extension to protect against a boutonniere-like posture.

- If stable in extension, closed treatment is adequate.

- If acute redislocation occurs, suspect volar lip fracture (see Fig. 7).

If the injury is a long-term recurrent condition and reducible, tape or splint, depending on the player and position on the team.

Surgical management may be necessary if recurrent dislocation occurs after 6 weeks of splinting; MRI can be quite helpful.

PIP Joint Dislocations (Volar)

This injury is much less common than the dorsal dislocation and can be very challenging to reduce on the sidelines. Instead of the simple distraction of the dorsal dislocation, in the volar dislocation, the MP joint and the PIP joint should flexed to reduce the tension of the lateral bands, and then gentle traction should permit dorsal translation of the middle phalanx. The central slip can be ruptured, so if the joint is stable in extension, treat as a boutonniere with the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint permitted to flex, while the PIP joint is held in extension.

Injuries to the Wrist

It is surprising how infrequently serious injuries to the wrist occur in football, given the players’ speed, size, and impact loading of the wrist at nearly every position on every play. Nonetheless, the time-honored saying, “beware of the sprained wrist” is worth retaining. All wrist “sprains,” especially those that become swollen, should be carefully examined in a setting that permits a thorough assessment. Where is the greatest tenderness? Does a certain motion or position cause pain? If the wrist is swollen with guarding to movement, X-rays are required to look for fractures or instability patterns.

The posteroanterior (PA) view of the wrist in ulnar deviation can show the scaphoid in the extended position for detecting a fracture. This position also shows a gap between the scaphoid and lunate because the scapholunate ligament is torn (Fig. 8). The lateral view is necessary, especially when dislocation is present (Fig. 9a, b), and this projection can be startling. Advanced imaging, CT or MRI or both, is often needed to complete the assessment. Before ordering those tests, the physician should communicate a preliminary diagnosis to the radiologist to ensure the optimal examination.

Fig. 8.

Posteroanterior view of the wrist in ulnar deviation shows a gap between the scaphoid and lunate.

Fig. 9.

(a, b) A trans-scaphoid perilunate injury in a middle linebacker. The player’s median nerve function was present but minimal.

The following specific injuries to the wrist may be seen.

Scaphoid Fracture

Any player with persistent acute wrist pain should be examined for a suspected fracture or ligament injury. Scaphoid fractures can be subtle with minimal swelling or pain. Tenderness in the snuff box in ulnar deviation raises the level of suspicion. These can be imperceptible with plain X-ray, depending on technique and equipment. If there is a high degree of suspicion, CT scanning is usually the next study. If ligament injuries are also of concern, MRI can be very helpful.

Time of discovery

- Variable.

- When swelling and pain is prominent, the assessment is immediate, and the fracture frequently seen.

- With less severe pain and minimal swelling, the fracture may not be discovered until a later time due to the lack of symptoms.

- On occasion, a fibrous nonunion of a scaphoid may be discovered months or years after the primary injury. The player can suffer a standard impact load, have pain, but little swelling. At first glance, the X-rays show a gap but instead of jagged fracture lines, a smoother and sclerotic zone is seen between the halves of the bone.

Immediate management

Once the diagnosis is made, if there is displacement, operative fixation is usually the preferred treatment because the likelihood of fracture union within weeks is high. Nondisplaced fractures can be immobilized in a short-arm thumb spica. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS) can speed healing, with or without internal fixation, and is recommended and covered by third-party payers (Fig. 10). Play should not be permitted until union, determined by CT scan, can be confirmed.

Fig. 10.

A wideout and return specialist fractured his scaphoid mid-season. Internal fixation and ultrasound stimulation seemed to facilitate healing and permitted return to play sooner than expected—a rare but possible outcome.

Intercarpal Ligament Injuries With or Without Fracture

Scapholunate-ligament tears, perilunate dislocations, and trans-scaphoid perilunate injuries are not rare and seldom subtle. The pain, swelling, and deformity compel urgent assessment and imaging. The management choices and complexity of these injuries are beyond the scope of this article, but an assessment and documentation of median and ulnar nerve function immediately after discovery is important. These injuries can require immediate emergency transfer to a nearby inpatient facility (Fig. 9a, b).

A scapholunate ligament tear is an intercarpal ligament injury that requires a substantial impact load to the wrist in a position of extension. Unless there was a pre-existent tear, this injury is quite painful and swollen. The player usually resists moving the wrist at all due to the painful instability. Prompt surgical treatment offers the most promising outcome and return to sport. The specific procedures recommended vary; I prefer a version of a modified Brunelli procedure [2].

Summary

The care of hand and wrist injuries in football during the game and in-season requires a balance: optimizing the clinical outcome while minimizing interruption of the player’s participation. I find it best to communicate clearly with all parties on the tradeoffs regarding different care pathways. As long as the patient comes first and you treat the player as if they were your offspring, all other competing interests will be manageable. Second opinions are frequently sought, and this is an expected impulse on the part of parents, agents, and teams. I look at these as opportunities to learn. The more explicit and reasoned your plan is, including the likely timeline and return to play, the better. Proffering an expected time-in-splint or return to training is not, of course, a guarantee. But a plan provides some guideposts and defined milestones (a healed fracture, for instance) before the next phase of recovery and ultimately a return to play.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-hss-10.1177_15563316231153845 for Football Injuries of the Hand and Wrist: Acute Care and Management by Robert N. Hotchkiss in HSS Journal®: The Musculoskeletal Journal of Hospital for Special Surgery

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Human/Animal Rights: All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was not necessary for this technical article.

Required Author Forms: Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the online version of this article as supplemental material.

References

- 1.Ellsasser JC, Stein AH. Management of hand injuries in a professional football team: review of 15 years of experience with one team. Am J Sports Med. 1979;7(3):178–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia-Elias M, Lluch AL, Stanley JK. Three-ligament tenodesis for the treatment of scapholunate dissociation: indications and surgical technique. J Hand Surg. 2006;31(1):125–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayter CL, Gold SL, Potter HG. Magnetic resonance imaging of the wrist: bone and cartilage injury. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2013;37(5):1005–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mall NA, Carlisle JC, Matava MJ, Powell JW, Goldfarb CA. Upper extremity injuries in the National Football League: part I: hand and digital injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(10):1938–1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDevitt ER, Roberts WO. On-site treatment of PIP joint dislocations. Phys Sportsmed. 1998;26(8):85–86. 10.3810/psm.1998.08.1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Werner BC, Belkin NS, Kennelly S, et al. Injuries to the collateral ligaments of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb, including simultaneous combined thumb ulnar and radial collateral ligament injuries, in National Football League athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(1):195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolfe SW, Pederson WC, Kozin SH, Cohen MS. Green’s Operative Hand Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2021. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-hss-10.1177_15563316231153845 for Football Injuries of the Hand and Wrist: Acute Care and Management by Robert N. Hotchkiss in HSS Journal®: The Musculoskeletal Journal of Hospital for Special Surgery