Abstract

The gut microbiota is known to have significant involvement in the regulation of lipogenesis and adipogenesis, yet the mechanisms responsible for this relationship remain poorly understood. The current study aims to provide insight into the potential mechanisms by which the gut microbiota modulates lipogenesis in chickens. Using chickens fed with a normal-fat diet (NFD, n = 5) and high-fat diet (HFD, n = 5), we analyzed the correlation between gut microbiota, cecal metabolomics, and lipogenesis by 16s rRNA sequencing, miRNA and mRNA sequencing as well as targeted metabolomics analysis. The potential metabolite/miRNA/mRNA axis regulated by gut microbiota was identified using chickens treated with antibiotics (ABX, n = 5). The possible mechanism of gut microbiota regulating chicken lipogenesis was confirmed by fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) from chickens fed with NFD to chickens fed with HFD (n = 5). The results showed that HFD significantly altered gut microbiota composition and enhanced chicken lipogenesis, with a significant correlation between 3. Furthermore, HFD significantly altered the hepatic miRNA expression profiles and reduced the abundance of hepatic butyric acid. Procrustes analysis indicated that the HFD-induced dysbiosis of the gut microbiota might affect the expression profiles of hepatic miRNA. Specifically, HFD-induced gut microbiota dysbiosis may reduce the abundance of butyric acid and downregulate the expression of miR-204 in the liver. Multiomics analysis identified ACSS2 as a target gene of miR-204. Gut microbiota depletion by an antibiotic cocktail (ABX) showed a gut microbiota-dependent manner in the abundance of butyric acid and the expression of miR-204/ACSS2, which have been observed to be significantly correlated. Fecal microbiota transplantation from NFD chickens into HFD chickens effectively attenuated the HFD-induced excessive lipogenesis, elevated the abundance of butyric acid and the relative expression of miR-204, and reduced the expression of ACSS2 in the liver. Mechanistically, our results showed that the gut microbiota plays an antiobesity role by regulating the butyric acid/miR-204/ACSS2 axis in chickens. This work contributed to a better understanding of the functions of gut microbiota in regulating chicken lipogenesis.

Key words: gut microbiota, lipogenesis, hepatic miRNA expression, butyric acid, ACSS2

INTRODUCTION

Over the past few decades, the growth rate of chickens has experienced a noteworthy improvement due to the continuous advancements made in breeding, nutrition, immunity, and environmental management. Nevertheless, this progress has been accompanied by an excessive accumulation of body fat, particularly abdominal fat (Tian et al., 2022). Excessive fat deposition is deemed undesirable in the poultry industry as it adversely affects feed efficiency, meat production, reproductive performance, and disease resistance ability (Nematbakhsh et al., 2021). Numerous endeavors have been undertaken to reduce abdominal fat accumulation via diverse approaches, including genetic selection, nutritional strategies, and environmental management. Furthermore, chicken has been employed as a suitable animal model to investigate the fundamental mechanisms of lipogenesis, owing to the high degree of genomic sequence homology with humans. Hence, unraveling the mechanisms of lipogenesis and fat deposition could provide valuable information for studying human obesity or obesity-related disease while also contributing to the control of abdominal fat deposition in chickens.

Abdominal fat deposition is a complex biological process regulated by multiple genetic, nutritional, and environmental factors. Gut microbiota, also considered the second genome, is a complex community of hundreds of microorganisms. The performance of host traits is not only regulated by its own genes but also affected by the gut microbiota. Recently, growing attention has been paid to investigating the association between gut microbiota and fat deposition due to their strong interplay indicated by recent studies in mice (Zhang et al., 2022b), humans (Wei et al., 2023), and livestock (Wen et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2021). For example, Chen et al. found that Prevotella copri in the gut microbial communities of pigs increases host fat deposition significantly by activating host chronic inflammatory responses through the TLR4 and mTOR signaling pathways (Chen et al., 2021). Wen et al. conducted an investigation into the potential role of duodenal and cecal microbiota in the regulation of chicken fat deposition. The study identified 2 cecal microbial taxa, Methanobrevibacter and Mucispirillum schaedleri, which exhibited a significant correlation with fat deposition (Wen et al., 2019). Although growing evidence has confirmed gut microbiota's effect on fat deposition, the specific mechanism by which gut microbiota regulates fat deposition remains inadequately understood, particularly in the context of chicken.

MicroRNAs (miRNA), a class of noncoding RNA, have been extensively researched and confirmed to play crucial roles in regulating lipogenesis and fat deposition. In chicken, many miRNAs, such as miR-128-3p, miR-27b-3p (Zhang et al., 2019b), miR-429-3p (Chao et al., 2020), miR-223 (Wang et al., 2021), and gga-miRNA-18b-3p (Sun et al., 2019), have been identified as critical factors involved in the regulation of preadipocyte differentiation and lipogenesis. Recent studies have revealed that the gut microbiota can influence obesity development by regulating the function of miRNA (Virtue et al., 2019; Du et al., 2021), suggesting the important role of gut microbiota-miRNA crosstalk in host lipogenesis and lipid metabolism. Numerous studies have confirmed the impact of gut microbiota on chicken lipogenesis; however, the potential of gut microbiota to act as an upstream regulatory factor to modulate miRNA function and subsequently impact chicken lipogenesis remains unclear. In the present study, we induced excessive hepatic lipogenesis and fat deposition in chickens through a high-fat diet (HFD). Subsequently, we analyzed alterations in gut microbiota and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) in the cecum, as well as the SCFAs, miRNA expression profiles, and transcriptome of the liver. Finally, we investigated the possible mechanisms that underlie the roles of gut microbiota in chicken lipogenesis by a joint analysis of multiomics data and fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). We hope that the present study could provide new insights into the understanding of the mechanism underlying the effect of gut microbiota on the regulation of chicken lipogenesis and fat deposition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All animal experiments were performed following the approval of the Animal Welfare Committee of Yangzhou University (permit number SYXK [Su] 2016-0020). A total of sixty 4-wk-old Heying black chickens were selected and randomly assigned to 4 groups: normal-fat diet (NFD, n = 10), HFD (n = 30), high-fat diet with fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT, n = 10), and antibiotic cocktail-treated (ABX, n = 10), respectively. There was no significant difference in mean body weight among the groups (P > 0.05).

Animal Treatments

The HFD group of chickens was subjected to a diet comprising basal feed and soybean oil (20%) for a duration of 4 wk, with the aim of inducing excessive lipogenesis and fat deposition. On the other hand, the ABX group of chickens was administered a mixture of 4 antibiotics via oral gavage for a period of 21 d, with the objective of depleting the gut microbiota. Each chicken was housed in an individual cage and provided with ad libitum access to food and water. The antibiotic mix consists of vancomycin (Macklin, Shanghai, China, 0.5 μg/mL), Ampicillin (Macklin, Shanghai, China, 1 μg/mL), Neomycin sulfate (Macklin, Shanghai, China, 1 μg/mL), and Metronidazole (Macklin, Shanghai, China, 1 μg/mL). Chickens in the ABX group were provided with ad libitum access to the water with 4 antibiotics.

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation

The FMT method refers to the previous study (Siegerstetter et al., 2018), with some modifications. Briefly, chickens in the NFD group were used as microbiota donors. The feces of donor chickens (n = 10, 8-wk-old) were collected and stored on ice in a sterile centrifuge tube. Fecal samples weighing 10 g were mixed with 60 mL of 0.75% sterile physiological saline and placed on ice. After settling the precipitate, the supernatant fluid was filtered by 5-layer sterile gauze to prepare a bacterial liquid. Twenty 4-wk-old chickens were fed with HFD for 4 wk to induce obesity. At 8 wk of age, the 20 obese chickens were randomly assigned to either the HFD (n = 10) or FMT (n = 10) groups. Chickens in the FMT group were used as recipients and given intragastric bacterial liquid administration for 2 wk (1 mL/d). Chickens in control (HFD) group were given intragastric administration of physiological saline for 2 wk (1 mL/d).

Sample Collection and Study Design

Following treatment with HFD, ABX, and FMT, a cohort of 5 healthy chickens with comparable body weights was chosen from each group. The body weight data were recorded. Chickens were sacrificed by cervical dislocation under ether anesthesia. Chickens in the study of NFD vs. HFD were sacrificed at 8-wk-old, chickens in the NFD vs. ABX study were sacrificed at 7-wk-old, and chickens in the HFD vs. FMT study were sacrificed at 8-wk-old, respectively. The abdominal fat tissues were isolated and weighed, while blood samples were collected through venipuncture, and the serum was obtained through centrifugation and stored at 4°C. The liver tissues and cecal content were procured, transferred to microcentrifuge tubes, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and preserved at −80°C until further analysis. The study design is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The flowchart of the study design.

Lipogenic Indicator Detection

The hepatic triglyceride content (TG) was assessed using a TG kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China) as per the manufacturer's guidelines. The serum TG, serum total cholesterol (TC), serum high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and serum low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels were quantified using TG, TC, HDL-C, and LDL-C assay kits (Jiancheng, Nanjing, China) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

16S rRNA Sequencing

Bacterial DNA was extracted from the cecal content using the HiPure Stool DNA Kits according to the manufacturer's instructions (Magen, Guangzhou, China). The quality and concentration of the extracted bacterial DNA were evaluated using NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer and agarose gel electrophoresis. Subsequently, the extracted DNA was employed as a template for PCR amplification of the bacterial V3/V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene, utilizing 341F (CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG) and 806R (GGACTACHVGGGTATCTAAT) primers. The PCR products were purified using AMPure XP Beads (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA) and quantified using ABI StepOnePlusReal-Time PCR System (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). The purified products were sequenced using the PE250 model in the NovaSeq 6000 system.

The sequencing-derived raw reads underwent filtration to obtain clean reads by eliminating low-quality reads through the utilization of FASTP. The paired-end clean reads were merged as raw tags with FLASH. Noisy sequences of raw tags were filtered to obtain high-quality clean tags. The clean tags were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) with a minimum of 97% similarity via the UPARSE pipeline. The removal of all chimeric reads was executed using the UCHIME method to obtain effective tags. The tag sequence with the highest abundance was selected as the representative sequence within each OTU cluster. The representative OTU sequences were classified into organisms by a naïve Bayesian model using an RDP classifier based on the SILVA database. The community composition of each group was visualized by the ggplot2 R package. Alpha diversity was measured by the Sob, Chao1, ACE, Shannon, and Simpson indices. Beta diversity was examined with principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) using weighted UniFrac distances. Differentially abundant taxa were identified using the Vegan R package. The functional analysis of the OTUs was performed using Tax4Fun based on the SILVA annotation. Correlation analysis between differentially abundant taxa and lipogenic indicators was performed using the psych R package.

MiRNA Sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from the liver tissues using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was employed to enrich RNA molecules within the size range of 18 to 30 nt. Subsequently, the RNAs were ligated with 3′ and 5′ adapters. The resulting ligation products were reverse transcribed via PCR amplification, and PCR products measuring 140 to 160 bp in length were enriched to generate a cDNA library. The cDNA library was then sequenced using Illumina HiSeq X Ten by Gene Denovo Biotechnology Co. (Guangzhou, China). Raw reads from the miRNA sequencing were processed according to our previous study (Ding et al., 2022) to obtain clean tags using FastQC. MicroRNAs were identified by aligning the clean tags against the miRBase database release 22 (Kozomara and Griffiths-Jones, 2011). Novel miRNAs were predicted using mirdeep2 software. The miRNA expression level was calculated and normalized to transcripts per million (TPM). Target gene prediction of miRNA was performed using Miranda and TargetScan software. GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of target genes were performed using the ClusterProfiler package in the R project.

RNA Sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from the liver tissues using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The mRNA was enriched from total RNA using Oligo(dT) beads, broken into short fragments using fragmentation buffer, and reversely transcribed into cDNA using NEBNext Ultra RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). The resulting double-stranded cDNA was subjected to end-repair, A-tailing, and adaptor-ligation, and subsequently sequenced using Illumina NovaSeq 6000 by Gene Denovo Biotechnology Co. (Guangzhou, China). The raw reads were filtered to obtain high-quality clean reads using the fastp software. The clean reads were aligned with the ribosome RNA (rRNA) database using Bowtie2 to remove reads mapped to rRNA. Then the remaining clean reads were mapped to the chicken (Gallus gallus) reference genome (GRCg6a) using HISAT2. Fragment per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) value was calculated to quantify the relative expression of transcript using RSEM software. The RNA-seq data were validated using RT-qPCR. The primers for the RT-qPCR were designed using the online tool Primer-BLAST (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast). The primer sequences utilized in this process are provided in Table S1.

Detection of Short-Chain Fatty Acids by GC-MS

Each sample of cecal content weighing 50 ± 5 mg was individually placed into 2 mL EP tubes, followed by extraction with 1 mL of dH2O and vortexing for 10 s. The sample was then subjected to grinding for 4 min at 40 Hz and homogenization by sonication for 5 min in an ice-water bath, which was repeated 3 times. Following homogenization, the sample was centrifuged for 20 min at 5,000 rpm and 4°C. Approximately 0.8 mL of supernatant was transferred to 2 mL EP tubes containing 0.1 mL of 50% H2SO4 and 0.8 mL of internal standard. The mixture was vortexed for 10 s, shaken for 10 min, sonicated for 10 min, and centrifuged at 4°C for 15 min at 10,000 rpm. The supernatant was collected and subjected to gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy (GC-MS) analysis using the SHIMADZU GC2030-QP2020 NX gas chromatography-mass spectrometer.

Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining

The abdominal fat tissue was collected and fixed with 10% formalin for histological examination. The fixed tissue was cut into 4 to 5 μm sections and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The slides were observed under bright field microscopy (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical Analysis

Experimental data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Lipogenic indicators, metabolite abundance, and gene expression between different groups were compared using the Student t test. Alpha diversity indices between groups were compared using Welch's t test. Beta diversity distance between groups was accessed and compared using Welch's t test and ANOSIM test. Differentially abundant taxa were identified using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test with P < 0.05. Correlation analysis was performed using the Pearson method of the psych R package and visualized by the pheatmap R package. Differentially expressed miRNAs (DEmiRNAs) and mRNAs (DEmRNAs) were identified by edgeR software with fold change (FC) >2 and P < 0.05. The correlation between the cecal microbiome and hepatic miRNA-seq data was analyzed by the Procrustes analysis using the Procrustes function in the vegan R package. A P < 0.05 and P < 0.01 indicate significant differences.

RESULTS

High-Fat Diet Enhanced Lipogenesis and Fat Deposition in Chicken

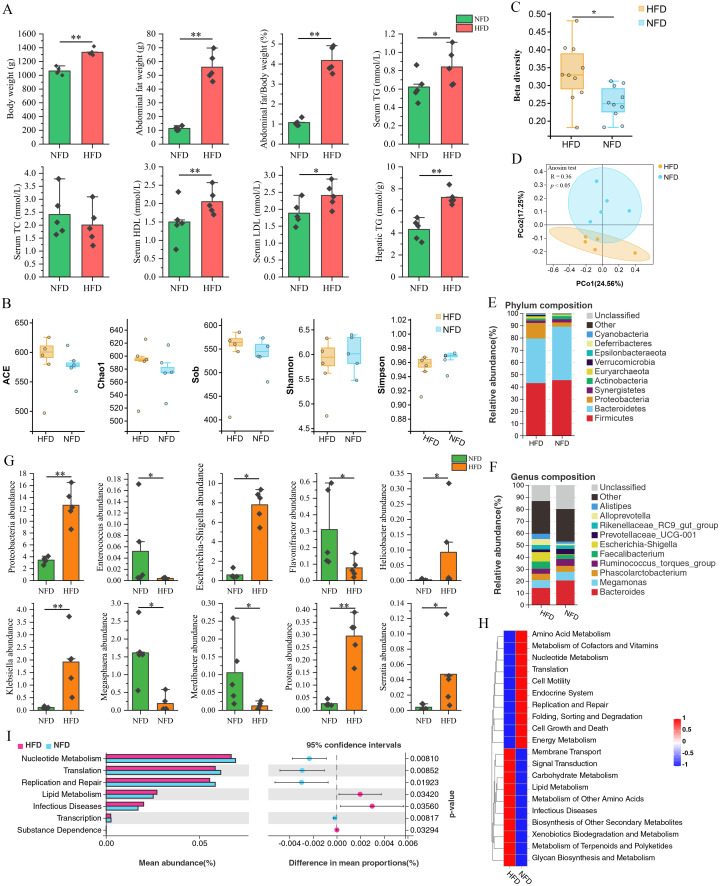

An HFD was administered to chickens as a means of inducing an obese phenotype. Following a 4-wk induction period, the chickens who received the HFD exhibited a statistically significant increase in body weight (P < 0.01), abdominal fat weight (P < 0.01), serum TG (P < 0.05), serum HDL (P < 0.01), serum LDL (P < 0.05), and hepatic TG (P < 0.01) when compared to those who received an NFD (Figure 2A). The results indicated that an HFD-induced obese chicken model with enhanced lipogenesis and fat deposition was established.

Figure 2.

Effect of HFD on lipogenesis and gut microbiota of chicken. (A) Effect of HFD on lipogenesis of chicken. HFD significantly increased body weight, abdominal fat weight, serum TG, serum HDL, serum LDL, and hepatic TG. (B) Effect of HFD on alpha diversity of cecal microbiota. (C and D) Effect of HFD on beta diversity of cecal microbiota. (E) Community composition at the phylum level. (F) Community composition at the genus level. (G) Differentially abundant taxa at the phylum and genus levels. (H) Heatmap of the gut microbiota function. (I) Functional difference analysis of cecal microbiota between NFD and HFD chickens. * indicates P < 0.05, ** indicate P < 0.01.

Effect of High-Fat Diet on Gut Microbiota

The impact of an HFD on the gut microbiota of chickens was analyzed using 16S rRNA sequencing. As indicated by Sob, Chao1, ACE, Shannon, and Simpson indices, the alpha diversity of cecal microbiota was not significantly affected by HFD (P > 0.05) (Figure 2B). However, a significant difference (P < 0.05) in the beta diversity of cecal microbiota community structures was observed between NFD and HFD groups (Figure 2C and D). At the phylum level, chickens fed with an HFD showed a significantly increased abundance of Proteobacteria (P < 0.01), an increased Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio (from 1.04 to 1.18), and decreased abundance of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes (P > 0.05). The abundance of Proteobacteria phylum increased from 3.45 to 12.67%, while the abundance of Bacteroidetes decreased from 43.40 to 34.37%, respectively (Figure 2E). At the genus level, the NFD and HFD groups exhibited differential abundance in 9 genera, namely Escherichia-Shigella, Klebsiella, Megasphaera, Flavonifractor, Proteus, Merdibacter, Helicobacter, Enterococcus, and Serratia. The HFD feeding significantly increased the abundance of Escherichia-Shigella (P < 0.01), Klebsiella (P < 0.01), Proteus (P < 0.01), Helicobacter (P < 0.05), and Serratia (P < 0.05), while significantly decreasing the abundance of Megasphaera, Flavonifractor, Merdibacter, and Enterococcus (P < 0.05) (Figure 2F and G).

Subsequently, we employed Tax4Fun to predict the function of the chicken cecal microbiota derived from the NFD and HFD cohorts. As indicated in Figure 2H, the cecal microbiota of chickens from distinct groups exhibited distinct functional profiles, suggesting that the HFD intervention had a discernible impact on the functions of the cecal microbiota. Differential analysis revealed that the HFD intervention significantly increased the abundance of microbiota implicated in lipid metabolism, infectious diseases, and substance dependence (P < 0.05). Conversely, the HFD intervention markedly diminished the abundance of microbiota associated with nucleotide metabolism (P < 0.01), translation (P < 0.01), replication and repair (P < 0.05), and transcription (P < 0.01) (Figure 2I).

Correlation Between Gut Microbiota and Lipogenesis

Studies have shown that gut microbiota dysbiosis is closely associated with the development of obesity (Liu et al., 2021). Thus, the present study investigated the potential relationship between differentially abundant microbiota and lipogenic indicators through correlation analysis. The findings, as depicted in Figure 3A, revealed a significant positive correlation between the abundance of Proteobacteria phylum and abdominal fat weight (P < 0.05), hepatic triglyceride (P < 0.05), serum triglyceride (P < 0.01), and serum LDL (P < 0.05). At the genus level, abdominal fat weight showed a significant positive correlation with the abundance of Escherichia-Shigella and significant negative correlations with the abundance of Megasphaera (P < 0.01), Enterococcus (P < 0.05), and Flavonifractor (P < 0.05). Hepatic TG showed significant positive correlations with the abundance of Escherichia-Shigella (P < 0.05), Klebsiella (P < 0.01), Proteus (P < 0.05), Helicobacter (P < 0.05), and Serratia (P < 0.01) and negative correlations with the abundance of Megasphaera (P < 0.01), Flavonifractor (P < 0.01), Merdibacter (P < 0.05), and Enterococcus (P < 0.05). The serum HDL content was significantly positively correlated to the abundance of Serratia and negatively correlated to the abundance of Merdibacter. The serum TG content was significantly positively associated with the abundance of Escherichia-Shigella (P < 0.05), Klebsiella (P < 0.01), Proteus (P < 0.05), and Helicobacter (P < 0.05). These results suggested that HFD-induced gut microbiota dysbiosis affected lipogenesis and fat deposition in chickens.

Figure 3.

Effect of HFD on hepatic miRNA expression. (A) Correlations between differential microbiota and lipogenic indicators. (B) Volcano plot of DEmiRNAs between NFD and HFD groups. (C) GO biological process enrichment analysis of target genes of DEmiRNAs. (D) KEGG pathway enrichment of target genes of DEmiRNAs. (E) Procrustes analysis of the microbiome and miRNA-seq data. (F) Relative expression of DEmiRNAs with the top expression level (TPM > 10) using RT-qPCR. (G) The relative expression levels of DEmiRNAs with the top expression level (TPM > 10) in liver samples from NFD and ABX groups.

High-Fat Diet-Induced Gut Microbiota Alteration Affected Liver miRNA Expression Profile

Through miRNA sequencing, we analyzed the miRNA expression profile in the liver of chickens from both the NFD and HFD groups. A total of 1,056 miRNAs were identified from 10 liver samples, consisting of 423 miRNAs previously known to chickens and 633 novel miRNAs. Applying a threshold of P < 0.05 and FC > 2, we detected 47 differentially expressed miRNAs between the NFD and HFD groups, comprising of 27 upregulated miRNAs and 20 downregulated miRNAs (Figure 3B, Table S2). Target prediction analysis revealed 8,306 possible target genes for the 47 differentially expressed miRNAs. Subsequently, the target genes underwent GO and KEGG enrichment analysis to elucidate the potential functions of the miRNAs that were differentially expressed. The results revealed a total of 537 significantly enriched GO terms, which comprised 423 biological process terms, 76 cellular component terms, and 38 molecular function terms (Table S3). Importantly, target genes were involved in the lipid metabolic process or lipid biosynthetic process terms (Figure 3C). Furthermore, KEGG analysis identified 36 pathways that were significantly enriched, including several pathways related to lipogenesis, such as peroxisome, fatty acid metabolism, and biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids (Figure 3D, Table S4). A Procrustes analysis was conducted utilizing microbiome and miRNA transcriptome data to examine the association between gut microbiota composition and miRNA expression. The results, as depicted in Figure 3E, revealed a noteworthy correlation between the structure of cecal microbiota and miRNA expression profile (P < 0.05, M2 = 0.42), suggesting the potential involvement of gut microbiota in the regulation of hepatic miRNA expression.

Gut Microbiota Regulated the Expression of miR-204 in the Liver

In order to identify miRNAs regulated by gut microbiota, we initially assessed the relative expression of 6 miRNAs that exhibited the highest expression levels (TPM > 10) via RT-qPCR. The results obtained from RT-qPCR were consistent with those obtained from miRNA sequencing, indicating similar trends in miRNA expression (Figure 3F). Specifically, gga-miR-6606-5p was significantly upregulated, whereas gga-miR-375, novel-m0003-5p, miR-375-y, gga-miR-204 (miR-204), and gga-miR-211 were significantly downregulated in response to high-fat diet treatment. To further identify miRNAs regulated by cecal microbiota, we implemented ABX treatment to deplete the gut microbiota and subsequently assessed the expression of the aforementioned 6 miRNAs through RT-qPCR. Our findings indicate that miR-204 exhibited the most notable alterations, thereby implying that its expression may be influenced by gut microbiota (Figure 3G).

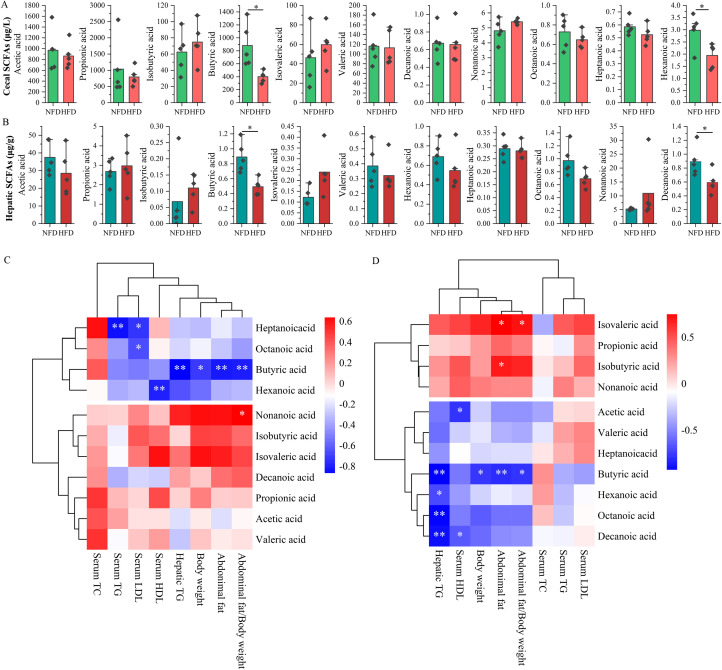

Butyric Acid Correlated With the Lipogenesis of Chicken

Studies have shown that SCFAs might act as a bridge between the gut and the liver (Liu et al., 2022b; Yin et al., 2023). Consequently, we hypothesized that alterations in gut microbiota induced by a HFD might regulate hepatic miR-204 expression by influencing the concentration of SCFAs in the liver. To test this hypothesis, we utilized GC-MS to measure the levels of cecal and hepatic SCFAs. Our findings, presented in Figure 4, demonstrate that HFD treatment significantly decreased the concentration of butyric acid in both the cecum and liver relative to the NFD chickens (P < 0.05). These results suggest that butyric acid may serve as a mediator linking gut microbiota and hepatic miRNA. Furthermore, the HFD treatment resulted in a significant reduction of hexanoic acid concentration in the cecum and decanoic acid concentration in the liver (P < 0.05). It is noteworthy that, although not statistically significant, the HFD treatment also led to a decrease in the concentrations of acetic acid and propionic acid in the cecum (Figure 4A and B).

Figure 4.

Correlations between SCFAs and lipogenesis. Effect of HFD on the concentration of cecal SCFAs (A) and hepatic SCFAs (B). Correlations between cecal SCFAs and lipogenic indicators (C) hepatic SCFAs and lipogenic indicators (D). * indicates P < 0.05, ** indicate P < 0.01.

Correlation analysis showed that the cecal butyric acid concentration was significantly negatively correlated with body weight (P < 0.05), abdominal fat weight (P < 0.01), abdominal fat/body weight (P < 0.01), and hepatic TG content (P < 0.01). Hexanoic acid showed a significantly negative correlation with serum HDL content (P < 0.01) (Figure 4C). In the liver, butyric acid indicated significant negative correlations with body weight (P < 0.05), abdominal fat weight (P < 0.01), abdominal fat/body weight (P < 0.05), and hepatic TG content (P < 0.01) (Figure 4D). The concentrations of hepatic hexanoic acid, octanoic acid, and decanoic acid also exhibited significant correlations with the hepatic TG content. These results implied that butyric acid might play an important role in regulating the lipogenesis of chicken.

Butyric Acid Inhibits Lipogenesis by Regulating the miR-204/ACSS2 Axis

Then we investigated whether the gut microbiota could regulate miR-204 expression by affecting hepatic butyric acid abundance using HFD feeding, ABX treatment, and correlation analysis. Our findings revealed a significant positive correlation between hepatic butyric acid concentration and relative miR-204 expression following HFD feeding (Figure 5A). We then depleted the gut microbiota and determined the cecal butyric acid concentration change. Like miR-204, ABX treatment significantly reduced hepatic butyric acid concentration, indicating that the gut microbiota regulates the concentration of butyric acid in the liver by the gut-liver axis (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

(A) Partial correlation between the abundance of butyric acid and the relative expression of miR-204 in the liver. (B) Effect of HFD and ABX on the abundance of hepatic butyric acid. (C) Volcano plot of DEmRNAs between NFD and HFD groups. (D) The miRNA-mRNA interaction network based on DEmiRNAs and DEmRNAs. GO (E) and KEGG pathway (F) enrichment analysis of the miRNA-mRNA interaction network. (G) Target genes of miR-204. (H) Effects of HFD and ABX on the relative expression of miR-204 and ACSS2. (I) Correlation between the abundance of butyric acid and the relative expression of ACSS2 in the liver. (J) Correlation between the relative expression of miR-204 and ACSS2 in the liver.

Studies have shown that miRNA functions mainly by binding with the 3′UTR of target mRNA to enhance its degradation or inhibit its translation (Bartel, 2004; Fabian et al., 2010). To identify target mRNA regulated by miR-204, we sequenced the hepatic transcriptome of chickens fed with HFD and NFD using RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). A total of 271 DEmRNAs were obtained between the 2 groups, with 162 genes exhibiting upregulation and 109 genes exhibiting downregulation (Figure 5C). The expression of the top 10 DEmRNAs was subsequently validated through RT-qPCR, which revealed similar expression trends as those observed in the RNA-seq data, thereby confirming the reliability and accuracy of the RNA-seq data (Figure S1). Then we constructed a miRNA-mRNA interaction network was constructed based on the DEmiRNAs and DEmRNAs identified between NFD and HFD groups. The resulting network consisted of 38 DEmiRNAs and 108 DEmRNAs, which formed 275 miRNA-mRNA interactions (Figure 5D). To investigate the potential role of the constructed network in regulating chicken lipogenesis, the DEmRNAs involved in the network were subjected to GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis. The analysis revealed that the DEmRNAs were significantly enriched in 475 GO terms, including 345 biological process terms, 104 molecular function terms, and 26 cellular component terms (Table S5). The KEGG analysis identified 15 pathways that were significantly enriched, such as steroid biosynthesis, steroid hormone biosynthesis, and retinol metabolism (Table S6). Notably, numerous biological processes and pathways related to lipid metabolism were identified, including the lipid metabolic process, lipid biosynthetic process, steroid biosynthesis pathway, and steroid hormone biosynthesis pathway (Figure 5E and F).

As shown in Figure 5G, miR-204 interacted with 22 DEmRNAs, forming a subnetwork with 22 miRNA-mRNA interactions. Our investigation revealed that ACSS2, a well-established gene involved in lipogenesis, may be a target gene of miR-204. In order to investigate the potential regulatory effects of butyric acid on lipogenesis via miR-204 and ACSS2, we conducted an assessment of the expression levels of miR-204 and ACSS2 following HFD feeding and ABX treatment. Our findings showed that, like miR-204, the expression of ACSS2 was altered in a gut microbiota-dependent manner. Specifically, both HFD and ABX treatments resulted in a significant upregulation of ACSS2 expression, which was positively correlated with butyric acid abundance and negatively correlated with miR-204 expression levels (Figure 5H–J). The results suggested that the gut microbiota might regulate the hepatic lipogenesis of chicken through the butyric acid/miR-204/ACSS2 axis.

FMT Confirmed the Role of Butyric Acid/miR-204/ACSS2 Axis in the Lipogenesis of Chicken

In order to further confirm the role of the butyric acid/miR-204/ACSS2 axis in lipogenesis and fat deposition of chicken, we employed FMT technology to transplant fecal microbiota from NFD-fed chickens into HFD-fed chickens. We subsequently assessed the lipogenic indicators, butyric acid abundance, and relative expression of miR-204/ACSS2. Our findings, as depicted in Figure 6, demonstrate a significant reduction in body weight, abdominal fat weight, abdominal fat/body weight, serum TG, serum TC, serum HDL, and hepatic TG in the FMT group after 4 wk compared to the HFD group (P < 0.01 or P < 0.05). FMT treatment also significantly downregulated the relative expression of lipogenic marker genes ACC and FASN (P < 0.05). Furthermore, FMT significantly elevated the abundance of butyric acid and relative expression of miR-204, while reduced the relative expression of ACSS2 in the liver. These findings collectively suggest that gut microbiota dysbiosis induced by HFD enhances lipogenesis and fat deposition in chickens by modulating the butyric acid/miR-204/ACSS2 axis.

Figure 6.

Effects of FMT on lipogenesis of chicken. (A) Effects of FMT on lipogenesis. (B) Effect of FMT on hepatic butyric acid abundance. (C) Effects of FMT on the relative expression of miR-204 and ACSS2 in the liver. (D) Effect of FMT on abdominal fat deposition.

DISCUSSION

Although previous studies have demonstrated the significant roles of gut microbiota in regulating animal lipogenesis and fat deposition (Zhao et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2021; Heo et al., 2023), there is a paucity of studies examining the correlations between gut microbiota and chicken lipogenesis. The HFD has been reported to contribute to the development of obesity by modulating gut microbiota composition. Hence, the HFD has been widely considered a powerful tool for investigating the gut microbiota-host interactions linked to lipogenesis and obesity development (Shi et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020b, 2022). The current investigation aimed to examine the role of gut microbiota in lipogenesis by establishing an obese chicken model induced by an HFD and evaluating the impact of HFD on cecal microbiota. Our findings revealed that HFD markedly augmented lipogenesis and modified the composition of cecal microbiota in chickens. In accordance with recent studies, HFD significantly increased the abundance of Proteobacteria and reduced the abundance of Bacteroidetes at the phylum level (Li et al., 2019; Becker et al., 2020). Additionally, we observed an elevated Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio in the HFD group, which is a critical indicator linked to obesity (Pandit et al., 2018; Becker et al., 2020; Grigor'eva, 2020). Overall, the above results indicated the successful establishment of the HFD-induced obese chicken model and further suggested the critical roles of Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes phylum in the development of obesity.

At the genus level, 9 differentially abundant genera were identified between NFD and HFD groups. Notably, 3 genera with antiobesity properties, namely Megasphaera (Gao et al., 2022), Flavonifractor (Bailén et al., 2020), and Enterococcus (Kondoh et al., 2014), exhibited a significant decrease in abundance when subjected to HFD, thus implying a correlation between their reduced abundance and the HFD-induced obesity. It is noteworthy that our findings reveal a significant increase in the prevalence of opportunistic pathogens, including Escherichia-Shigella, Klebsiella, Proteus, Helicobacter, and Serratia, in response to HFD feeding. Recent studies have also indicated that obesity and HFD were accompanied by an increased abundance of Escherichia-Shigella, Klebsiella, Serratia, and Helicobacter genera (Palmas et al., 2021), suggesting that HFD-induced obesity may lead to microbiota dysbiosis, with these genera serving as potential microbial biomarkers of obesity.

Recently, accumulating evidence has confirmed a causal relationship between gut microbiota and lipogenesis in chicken (Zhang et al., 2019a, 2021). Our findings reveal a significant correlation between differentially abundant microbiota and lipogenic indicators, suggesting that gut dysbiosis induced by a high-fat diet may contribute to fat deposition and lipogenesis in chickens. Despite the established link between gut microbiota and lipogenesis, the precise mechanisms underlying this relationship remain poorly understood, particularly in the context of chickens. Recent studies have indicated that gut microbiota may influence host lipogenesis and the development of obesity by modulating miRNA function. For example, Du et al. found that betaine can improve obesity via the gut microbiota-derived miR-378a/YY1 regulatory axis (Du et al., 2021). Virtue et al. revealed that tryptophan-derived metabolites produced by the gut microbiota regulate energy expenditure and insulin sensitivity by controlling the expression of the miR-181 family in white adipocytes in mice (Virtue et al., 2019). Therefore, we ask whether the gut microbiota exerts its effect on lipogenesis and fat deposition by regulating miRNA expression in the liver. Using miRNA-seq, we identified 47 DEmiRNAs in the liver induced by HFD. To investigate the correlation between gut microbiota and hepatic miRNA expression profiles, we employed Procrustes analysis, a widely used method for analyzing the correlation of microbiome with other omics datasets (Nguyen et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2022a). Our findings revealed a significant correlation, indicating the involvement of gut microbiota in regulating hepatic miRNA expression. Our previous study has confirmed the efficacy of ABX treatment in depleting gut microbiota (Zhang et al., 2021). Subsequently, we depleted the gut microbiota by ABX treatment to identify the specific miRNA regulated by gut microbiota. Our findings revealed that the highly expressed DEmiRNA miR-204 exhibited the most significant expression alteration subsequent to gut microbiota depletion. Previous studies have reported that miR-204 regulates the differentiation of mammalian preadipocytes, thereby influencing fat deposition (Jin et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020). These results suggest that miR-204 may be a crucial target of gut microbiota in regulating the lipogenesis of chickens.

Studies have shown that gut microbiota plays a significant role in regulating host gene expression, primarily through its metabolic products, such as secondary bile acids (Jia et al., 2018), trimethylamine (Canyelles et al., 2018), and SCFAs (Morrison and Preston, 2016). SCFAs are the primary end-products of nondigestible carbohydrates fermentation that becomes available to the gut microbiota. SCFAs have been reported to regulate lipid metabolism by acting as lipogenic substrates (den Besten et al., 2013) or as signaling molecules binding to G-protein-coupled receptors (Du et al., 2021). According to recent studies, SCFAs can serve as a mediator between gut microbiota and host miRNA expression, thereby regulating host phenotype (Wang et al., 2020a; Liu et al., 2022b). The current investigation revealed that HFD treatment resulted in a significant reduction in butyric acid concentration in both the cecum and liver compared to NFD treatment. The concentration of butyric acid was found to be negatively correlated with lipogenesis and positively correlated with miR-204 expression in the liver. Furthermore, the depletion of gut microbiota using ABX significantly reduced the abundance of butyric acid and miR-204 expression. The aforementioned findings indicate that gut microbiota dysbiosis might downregulate the expression of miR-204 by reducing its metabolic product, butyric acid.

As is well known, miRNA primarily functions by binding to the 3′UTR of target mRNA to enhance its degradation or inhibit its translation (Bartel, 2004). Consequently, we constructed a miRNA-mRNA interaction network based on DEmiRNAs and DEmRNAs between NFD and HFD chickens to identify the target genes of miR-204. Our findings showed that miR-204 interacted with 22 DEmRNAs, and ACSS2, a well-known gene involved in lipogenesis (Xu et al., 2018), is likely a significant target gene of miR-204. Like miR-204, HFD and ABX treatments altered the expression of ACSS2 in a gut microbiota-dependent manner. The expression of ACSS2 was found to be positively associated with the abundance of butyric acid, while negatively correlated with the expression of miR-204. These results indicate that the butyric acid/miR-204/ACSS2 axis may be involved in the regulation of hepatic lipogenesis by the gut microbiota.

FMT involves the transfer of fecal microbiota suspension from a donor to a recipient with the aim of restoring microbiota diversity and composition. The dysbiosis of gut microbiota has long been recognized as a potential cause of metabolic disorders, including obesity and fatty liver (Han et al., 2022). Thus, FMT is emerging as a promising strategy to treat metabolic disorders by restoring the dysbiotic gut microbiota (Leong et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020). Furthermore, FMT holds potential as a tool for investigating the causal relationship between gut microbiota and host obesity development, as well as elucidating the underlying mechanisms (Ridaura et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2019). In this study, we employed FMT to transplant fecal microbiota from NFD-fed chickens to HFD-fed chickens, with the aim of confirming the involvement of butyric acid/miR-204/ACSS2 axis in the lipogenesis of chicken. The results revealed that FMT effectively alleviated the excessive lipogenesis and fat deposition induced by HFD treatment. Additionally, FMT significantly increased the abundance of butyric acid and the relative expression of miR-204, while decreasing the relative expression of ACSS2 in the liver. Taken together, our results showed that the HFD-induced cecal microbiota dysbiosis enhanced lipogenesis and fat deposition by regulating the butyric acid/miR-204/ACSS2 axis in the chicken.

Although our study revealed the potential role of gut microbiota-mediated butyric acid/miR-204/ACSS2 axis in the regulation of chicken lipogenesis, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of our research. Specifically, we did not validate the functions of this axis through in vitro experimentation, such as utilizing chicken liver cancer cells (LMH). As such, further investigation is required to explore the interaction between miR-204 and ACSS2 at the cellular level. Therefore, future work will focus on validating the function of the butyric acid/miR-204/ACSS2 axis and elucidating their regulatory relationships at the cellular level.

In summary, our study elucidated the involvement of gut microbiota/butyric acid/miR-204/ACSS2 in regulating lipogenesis and fat deposition in chickens. Mechanistically, the HFD-induced gut microbiota dysbiosis leads to a reduction in butyric acid levels, resulting in the downregulation of miR-204 and upregulation of ACSS2, thereby promoting lipogenesis in chickens. These findings offer novel perspectives on the interplay between the gut and liver in the regulation of chicken lipogenesis.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Guangzhou Genedenovo Biotechnology Co., Ltd. for assisting in RNA-seq analysis and bioinformatics analysis. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32102532), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2022M712698), the earmarked fund for CARS (CARS-41), and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD).

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.psj.2023.102856.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

REFERENCES

- Bailén M., Bressa C., Martínez-López S., González-Soltero R., Montalvo Lominchar M.G., Juan C.S., Larrosa M. Microbiota features associated with a high-fat/low-fiber diet in healthy adults. Front. Nutr. 2020;7 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2020.583608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel D.P. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker S.L., Chiang E., Plantinga A., Carey H.V., Suen G., Swoap S.J. Effect of stevia on the gut microbiota and glucose tolerance in a murine model of diet-induced obesity. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2020;96 doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiaa079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canyelles M., Tondo M., Cedó L., Farràs M., Escolà-Gil J.C., Blanco-Vaca F. Trimethylamine N-oxide: a link among diet, gut microbiota, gene regulation of liver and intestine cholesterol homeostasis and HDL function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19 doi: 10.3390/ijms19103228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao X., Guo L., Wang Q., Huang W., Liu M., Luan K., Jiang J., Lin S., Nie Q., Luo W., Zhang X., Luo Q. miR-429-3p/LPIN1 axis promotes chicken abdominal fat deposition via PPARγ pathway. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2020;8 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.595637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Fang S., Wei H., He M., Fu H., Xiong X., Zhou Y., Wu J., Gao J., Yang H., Huang L. Prevotella copri increases fat accumulation in pigs fed with formula diets. Microbiome. 2021;9:175. doi: 10.1186/s40168-021-01110-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Besten G., Lange K., Havinga R., van Dijk T.H., Gerding A., van Eunen K., Müller M., Groen A.K., Hooiveld G.J., Bakker B.M., Reijngoud D.J. Gut-derived short-chain fatty acids are vividly assimilated into host carbohydrates and lipids. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2013;305:G900–G910. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00265.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding H., Chen C., Zhang T., Chen L., Chen W., Ling X., Zhang G., Wang J., Xie K., Dai G. Identification of miRNA-mRNA networks associated with pigeon skeletal muscle development and growth. Animals (Basel) 2022;12:2509. doi: 10.3390/ani12192509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J., Zhang P., Luo J., Shen L., Zhang S., Gu H., He J., Wang L., Zhao X., Gan M., Yang L., Niu L., Zhao Y., Tang Q., Tang G., Jiang D., Jiang Y., Li M., Jiang A., Jin L., Ma J., Shuai S., Bai L., Wang J., Zeng B., Wu D., Li X., Zhu L. Dietary betaine prevents obesity through gut microbiota-drived microRNA-378a family. Gut Microbes. 2021;13:1–19. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2020.1862612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabian M.R., Sonenberg N., Filipowicz W. Regulation of mRNA translation and stability by microRNAs. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2010;79:351–379. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060308-103103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J.M., Rao J.H., Wei Z.Y., Xia S.Y., Huang L., Tang M.T., Hide G., Zheng T.T., Li J.H., Zhao G.A., Sun Y.X., Chen J.H. Transplantation of gut microbiota from high-fat-diet-tolerant cynomolgus monkeys alleviates hyperlipidemia and hepatic steatosis in rats. Front. Microbiol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.876043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigor'eva I.N. Gallstone disease, obesity and the firmicutes/bacteroidetes ratio as a possible biomarker of gut dysbiosis. J. Pers. Med. 2020;11:13. doi: 10.3390/jpm11010013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han T.R., Yang W.J., Tan Q.H., Bai S., Zhong H., Tai Y., Tong H. Gut microbiota therapy for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: evidence from randomized clinical trials. Front. Microbiol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.1004911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo S.W., Chung K.S., Yoon Y.S., Kim S.Y., Ahn H.S., Shin Y.K., Lee S.H., Lee K.T. Standardized ethanol extract of Cassia mimosoides var. nomame makino ameliorates obesity via regulation of adipogenesis and lipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells and high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Nutrients. 2023;15:613. doi: 10.3390/nu15030613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia W., Xie G., Jia W. Bile acid-microbiota crosstalk in gastrointestinal inflammation and carcinogenesis. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018;15:111–128. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y., Wang J., Zhang M., Zhang S., Lei C., Chen H., Guo W., Lan X. Role of bta-miR-204 in the regulation of adipocyte proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019;234:11037–11046. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondoh M., Shimada T., Fukada K., Morita M., Katada K., Higashimura Y., Mizushima K., Okamori M., Naito Y., Yoshikawa T. Beneficial effects of heat-treated Enterococcus faecalis FK-23 on high-fat diet-induced hepatic steatosis in mice. Br. J. Nutr. 2014;112:868–875. doi: 10.1017/S0007114514001792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozomara A., Griffiths-Jones S. miRBase: integrating microRNA annotation and deep-sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D152–D157. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong K.S.W., Jayasinghe T.N., Wilson B.C., Derraik J.G.B., Albert B.B., Chiavaroli V., Svirskis D.M., Beck K.L., Conlon C.A., Jiang Y., Schierding W., Vatanen T., Holland D.J., O'Sullivan J.M., Cutfield W.S. Effects of fecal microbiome transfer in adolescents with obesity: the gut bugs randomized controlled trial. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.30415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Li J., Mao G., Wu T., Lin D., Hu Y., Ye X., Tian D., Chai W., Linhardt R.J., Chen S. Fucosylated chondroitin sulfate from Isostichopus badionotus alleviates metabolic syndromes and gut microbiota dysbiosis induced by high-fat and high-fructose diet. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019;124:377–388. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.11.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B.N., Liu X.T., Liang Z.H., Wang J.H. Gut microbiota in obesity. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021;27:3837–3850. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i25.3837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Peng Z., Zhou L., Peng R., Li X., Zuo W., Gou J., Zhou F., Yu S., Huang M., Liu H. Short-chain fatty acid decreases the expression of CEBPB to inhibit miR-145-mediated DUSP6 and thus further suppresses intestinal inflammation. Inflammation. 2022;45:372–386. doi: 10.1007/s10753-021-01552-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison D.J., Preston T. Formation of short chain fatty acids by the gut microbiota and their impact on human metabolism. Gut Microbes. 2016;7:189–200. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2015.1134082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nematbakhsh S., Pei Pei C., Selamat J., Nordin N., Idris L.H., Razis A.F.A. Molecular regulation of lipogenesis, adipogenesis and fat deposition in chicken. Genes (Basel) 2021;12:414. doi: 10.3390/genes12030414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen Q.P., Karagas M.R., Madan J.C., Dade E., Palys T.J., Morrison H.G., Pathmasiri W.W., McRitche S., Sumner S.J., Frost H.R., Hoen A.G. Associations between the gut microbiome and metabolome in early life. BMC Microbiol. 2021;21:238. doi: 10.1186/s12866-021-02282-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmas V., Pisanu S., Madau V., Casula E., Deledda A., Cusano R., Uva P., Vascellari S., Loviselli A., Manzin A., Velluzzi F. Gut microbiota markers associated with obesity and overweight in Italian adults. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:5532. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-84928-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandit R.J., Hinsu A.T., Patel N.V., Koringa P.G., Jakhesara S.J., Thakkar J.R., Shah T.M., Limon G., Psifidi A., Guitian J., Hume D.A., Tomley F.M., Rank D.N., Raman M., Tirumurugaan K.G., Blake D.P., Joshi C.G. Microbial diversity and community composition of caecal microbiota in commercial and indigenous Indian chickens determined using 16s rDNA amplicon sequencing. Microbiome. 2018;6:115. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0501-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridaura V.K., Faith J.J., Rey F.E., Cheng J., Duncan A.E., Kau A.L., Griffin N.W., Lombard V., Henrissat B., Bain J.R., Muehlbauer M.J., Ilkayeva O., Semenkovich C.F., Funai K., Hayashi D.K., Lyle B.J., Martini M.C., Ursell L.K., Clemente J.C., Van Treuren W., Walters W.A., Knight R., Newgard C.B., Heath A.C., Gordon J.I. Gut microbiota from twins discordant for obesity modulate metabolism in mice. Science. 2013;341 doi: 10.1126/science.1241214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X., Zhou X., Chu X., Wang J., Xie B., Ge J., Guo Y., Li X., Yang G. Allicin improves metabolism in high-fat diet-induced obese mice by modulating the gut microbiota. Nutrients. 2019;11:2909. doi: 10.3390/nu11122909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegerstetter S.C., Petri R.M., Magowan E., Lawlor P.G., Zebeli Q., O'Connell N.E., Metzler-Zebeli B.U. Fecal microbiota transplant from highly feed-efficient donors shows little effect on age-related changes in feed-efficiency-associated fecal microbiota from chickens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018;84 doi: 10.1128/AEM.02330-17. e02330-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun G., Li F., Ma X., Sun J., Jiang R., Tian Y., Han R., Li G., Wang Y., Li Z., Kang X., Li W. gga-miRNA-18b-3p inhibits intramuscular adipocytes differentiation in chicken by targeting the ACOT13 gene. Cells. 2019;8:556. doi: 10.3390/cells8060556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian W., Hao X., Nie R., Ling Y., Zhang B., Zhang H., Wu C. Integrative analysis of miRNA and mRNA profiles reveals that gga-miR-106-5p inhibits adipogenesis by targeting the KLF15 gene in chickens. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2022;13:81. doi: 10.1186/s40104-022-00727-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virtue A.T., McCright S.J., Wright J.M., Jimenez M.T., Mowel W.K., Kotzin J.J., Joannas L., Basavappa M.G., Spencer S.P., Clark M.L., Eisennagel S.H., Williams A., Levy M., Manne S., Henrickson S.E., Wherry E.J., Thaiss C.A., Elinav E., Henao-Mejia J. The gut microbiota regulates white adipose tissue inflammation and obesity via a family of microRNAs. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019;11:eaav1892. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aav1892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Gao J., Ke W., Wang J., Li D., Liu R., Jia Y., Wang X., Chen X., Chen F., Hu X. Resveratrol reduces obesity in high-fat diet-fed mice via modulating the composition and metabolic function of the gut microbiota. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020;156:83–98. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Li Y., Qu L., Guo J., Dou T., Hu Y., Ma M., Wang K. Lipolytic gene DAGLA is targeted by miR-223 in chicken hepatocytes. Gene. 2021;767 doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2020.145184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T.Y., Tao S.Y., Wu Y.X., An T., Lv B.H., Liu J.X., Liu Y.T., Jiang G.J. Quinoa reduces high-fat diet-induced obesity in mice via potential microbiota-gut-brain-liver interaction mechanisms. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022;10 doi: 10.1128/spectrum.00329-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Wu H., Fan M., Yu R., Zhang Y., Liu J., Zhou X., Cai Y., Huang S., Hu Z., Jin X. Sodium butyrate inhibits migration and induces AMPK-mTOR pathway-dependent autophagy and ROS-mediated apoptosis via the miR-139-5p/Bmi-1 axis in human bladder cancer cells. FASEB J. 2020;34:4266–4282. doi: 10.1096/fj.201902626R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J., Dai W., Pan X., Zhong Y., Xu N., Ye P., Wang J., Li J., Yang F., Luo J., Luo M. Identifying the novel gut microbial metabolite contributing to metabolic syndrome in children based on integrative analyses of microbiome-metabolome signatures. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023;11 doi: 10.1128/spectrum.03771-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen C., Yan W., Sun C., Ji C., Zhou Q., Zhang D., Zheng J., Yang N. The gut microbiota is largely independent of host genetics in regulating fat deposition in chickens. ISME J. 2019;13:1422–1436. doi: 10.1038/s41396-019-0367-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T.R., Lin C.S., Chang C.J., Lin T.L., Martel J., Ko Y.F., Ojcius D.M., Lu C.C., Young J.D., Lai H.C. Gut commensal Parabacteroides goldsteinii plays a predominant role in the anti-obesity effects of polysaccharides isolated from Hirsutella sinensis. Gut. 2019;68:248–262. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-315458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H., Luo J., Ma G., Zhang X., Yao D., Li M., Loor J.J. Acyl-CoA synthetase short-chain family member 2 (ACSS2) is regulated by SREBP-1 and plays a role in fatty acid synthesis in caprine mammary epithelial cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018;233:1005–1016. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y., Sichler A., Ecker J., Laschinger M., Liebisch G., Höring M., Basic M., Bleich A., Zhang X.J., Kübelsbeck L., Plagge J., Scherer E., Wohlleber D., Wang J., Wang Y., Steffani M., Stupakov P., Gärtner Y., Lohöfer F., Mogler C., Friess H., Hartmann D., Holzmann B., Hüser N., Janssen K.P. Gut microbiota promote liver regeneration through hepatic membrane phospholipid biosynthesis. J. Hepatol. 2023;78:820–835. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2022.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu E.W., Gao L., Stastka P., Cheney M.C., Mahabamunuge J., Soto M.Torres, Ford C.B., Bryant J.A., Henn M.R., Hohmann E.L. Fecal microbiota transplantation for the improvement of metabolism in obesity: the FMT-TRIM double-blind placebo-controlled pilot trial. PLoS Med. 2020;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., Ding H., Chen L., Lin Y., Gong Y., Pan Z., Zhang G., Xie K., Dai G., Wang J. Antibiotic-induced dysbiosis of microbiota promotes chicken lipogenesis by altering metabolomics in the cecum. Metabolites. 2021;11:487. doi: 10.3390/metabo11080487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Jia X.B., Liu Y.C., Yu W.Q., Si Y.H., Guo S.D. Fenofibrate enhances lipid deposition via modulating PPARγ, SREBP-1c, and gut microbiota in ob/ob mice fed a high-fat diet. Front. Nutr. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.971581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Li F., Sun J.W., Li D.H., Li W.T., Jiang R.R., Li Z.J., Liu X.J., Han R.L., Li G.X., Wang Y.B., Tian Y.D., Kang X.T., Sun G.R. LncRNA IMFNCR promotes intramuscular adipocyte differentiation by sponging miR-128-3p and miR-27b-3p. Front. Genet. 2019;10:42. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., Li J., Wang N., Wang H., Yu L. Metagenomic analysis reveals microbiome and resistome in the seawater and sediments of Kongsfjorden (Svalbard, High Arctic) Sci. Total Environ. 2022;809 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.M., Sun Y.S., Zhao L.Q., Chen T.T., Fan M.N., Jiao H.C., Zhao J.P., Wang X.J., Li F.C., Li H.F., Lin H. SCFAs-induced GLP-1 secretion links the regulation of gut microbiome on hepatic lipogenesis in chickens. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:2176. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Wang W., Liu J.B., Wang Y., Hao J.D., Huang Y.J., Gao Y., Jiang H., Yuan B., Zhang J.B. ssc-miR-204 regulates porcine preadipocyte differentiation and apoptosis by targeting TGFBR1 and TGFBR2. J. Cell. Biochem. 2020;121:609–620. doi: 10.1002/jcb.29306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S., Jang C., Liu J., Uehara K., Gilbert M., Izzo L., Zeng X., Trefely S., Fernandez S., Carrer A., Miller K.D., Schug Z.T., Snyder N.W., Gade T.P., Titchenell P.M., Rabinowitz J.D., Wellen K.E. Dietary fructose feeds hepatic lipogenesis via microbiota-derived acetate. Nature. 2020;579:586–591. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2101-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.