Daratumumab is an anti-CD38–targeting antibody that depletes plasma cells. This study shows that daratumumab also disturbs humoral immune responses beyond depletion only and may be used as therapeutic in B cell–mediated autoimmune diseases.

Abstract

B cell–targeted therapies, such as CD20-targeting mAbs, deplete B cells but do not target the autoantibody-producing plasma cells (PCs). PC-targeting therapies such as daratumumab (anti-CD38) form an attractive approach to treat PC-mediated diseases. CD38 possesses enzymatic and receptor capabilities, which may impact a range of cellular processes including proliferation and differentiation. However, very little is known whether and how CD38 targeting affects B-cell differentiation, in particular for humans beyond cancer settings. Using in-depth in vitro B-cell differentiation assays and signaling pathway analysis, we show that CD38 targeting with daratumumab demonstrated a significant decrease in proliferation, differentiation, and IgG production upon T cell–dependent B-cell stimulation. We found no effect on T-cell activation or proliferation. Furthermore, we demonstrate that daratumumab attenuated the activation of NF-κB in B cells and the transcription of NF-κB–targeted genes. When culturing sorted B-cell subsets with daratumumab, the switched memory B-cell subset was primarily affected. Overall, these in vitro data elucidate novel non-depleting mechanisms by which daratumumab can disturb humoral immune responses. Affecting memory B cells, daratumumab may be used as a therapeutic approach in B cell–mediated diseases other than the currently targeted malignancies.

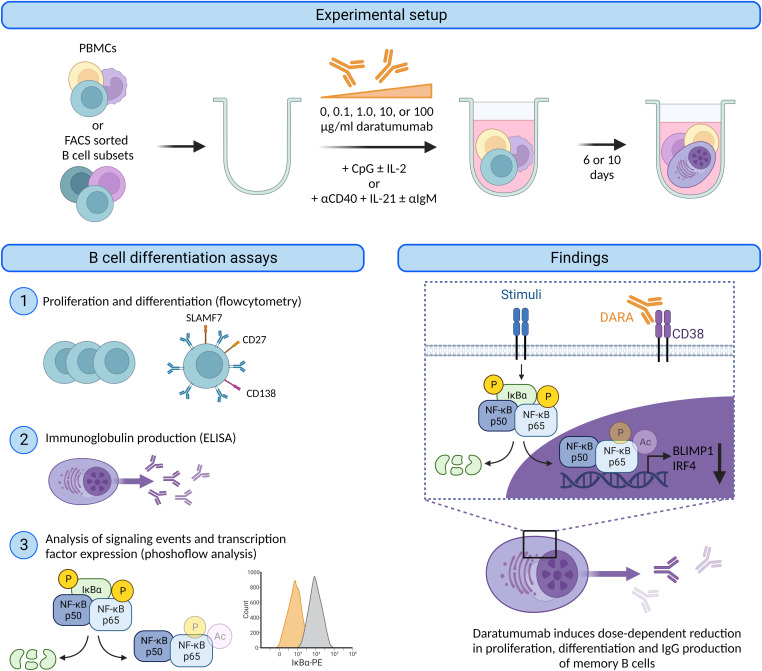

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

An essential process of humoral immunity is B-cell differentiation into antibody-producing plasma cells (PCs) (1). B cells can be activated through T cell–dependent (TD) activation, provided as help from T-follicular helper cells via CD40–CD40 ligand (CD40L) engagement, or through T cell–independent (TI) manners via TLR9 stimulation (1, 2). After activation, B cells are able to proliferate and differentiate into plasmablasts (PBs). Dependent on the activating conditions, B cells differentiate further into immunoglobulin-producing PCs or become memory B cells, which can respond rapidly upon subsequent encounter of cognate antigen (3). The cell surface molecules IgD, CD19, CD20, CD27, CD38, and CD138 are frequently used to identify the main B-cell populations in peripheral blood (4). The role of paired box 5 (PAX5), NF-κB, B lymphocyte–induced maturation protein-1 (BLIMP1), and interferon regulatory factor 4 (IRF4) as major drivers of B-cell identity and PC differentiation has been well established (1, 4, 5). In contrast, the mechanisms restricting PC differentiation remain incompletely understood.

Derailed B-cell function and PC generation is believed to play a key role in the pathogenesis of autoimmune disorders, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (6). A small fraction of autoimmune patients remains unresponsive to conventional B cell–depleting mAbs directed against CD20, where it is hypothesized that autoreactive PBs (CD20−CD38+) or PCs (CD20−CD38+CD138+) differentiate into long-lived PCs and reside in the bone marrow or inflamed tissues, where they are not depleted by these therapies. CD38-expressing malignant B cells and long-lived PCs can be targeted by novel B cell–targeted therapies such as the anti-CD38 mAbs daratumumab (DARA, trade name Darzalex) or isatuximab (trade name Sarclisa), which are currently approved for treatment of multiple myeloma (MM) (7, 8, 9, 10). These antibodies are highly efficacious and safe in MM patients. In MM patients, anti-CD38 therapy is associated with decreased immunoglobulin levels in serum, reduced autoantibody levels, increased frequency of infections, and reduced vaccination responses (to SARS-CoV-2) (8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15). However, it should be noted that these patients have altered function of the immune system induced by the disease itself and are heavily pretreated with other immunomodulatory drugs too (16). The mechanisms underpinning how anti-CD38 therapy influences normal PCs or PC differentiation beyond cancer settings have remained virtually unexplored.

CD38 has extensively been used to classify various lymphocyte subsets in humans and mice, as an activation marker or biomarker associated with poor prognosis in MM (17). CD38 is a multifunctional transmembrane glycoprotein possessing both enzymatic and receptor functions. Topologically, CD38 can behave as a type II or type III membrane protein depending on the orientation of the catalytic domain (18, 19, 20). Most commonly, the catalytic domain is situated in the extracellular compartment (type II). Given CD38’s multiple possible orientations and enzymatic functions, its substrate and products would be consumed or produced in the extracellular or intracellular compartment. The enzymatic functions of CD38 include the conversion of NAD+ into ADP-ribose (ADPR) and nicotinamide (NAM). Secondarily, it degrades NAD+ via cyclase activity resulting in cyclic ADPR (cADPR), which results in increased Ca2+ mobilization, shown by enzymatic assays of human CD38 (20, 21). Also, CD38 can metabolize NAD precursors and therefore regulates extracellular NAD+ availability, as shown in CD38 knockout mice (22, 23). Hereby, CD38 may influence activation of NAD+-dependent enzymes known to be involved in the canonical NF-κB pathway activation (24, 25). Besides this, CD38 is able to interact with CD31 to induce adhesion to endothelial cells (26). In B cells, activating CD38 mAbs have been shown to lower the threshold for B-cell receptor (BCR)–mediated B-cell activation (27). Furthermore, it has been shown in vitro that targeting CD38 with daratumumab, or removing CD38 with CRISPR/Cas9, inhibits the association of CD19 with the BCR, impairing BCR signaling in normal and malignant human B-cell lines (28).

Because daratumumab is known to interfere with B-cell activation in cell lines in vitro and because MM patients on daratumumab treatment show reduced immunoglobulin production in vivo, the effect of daratumumab may be beyond B-cell depletion only. Therefore, we focused in this study on the effects of daratumumab on the functional characteristics of B cells using in-depth in vitro B-cell differentiation assays and signaling pathway analysis.

Results

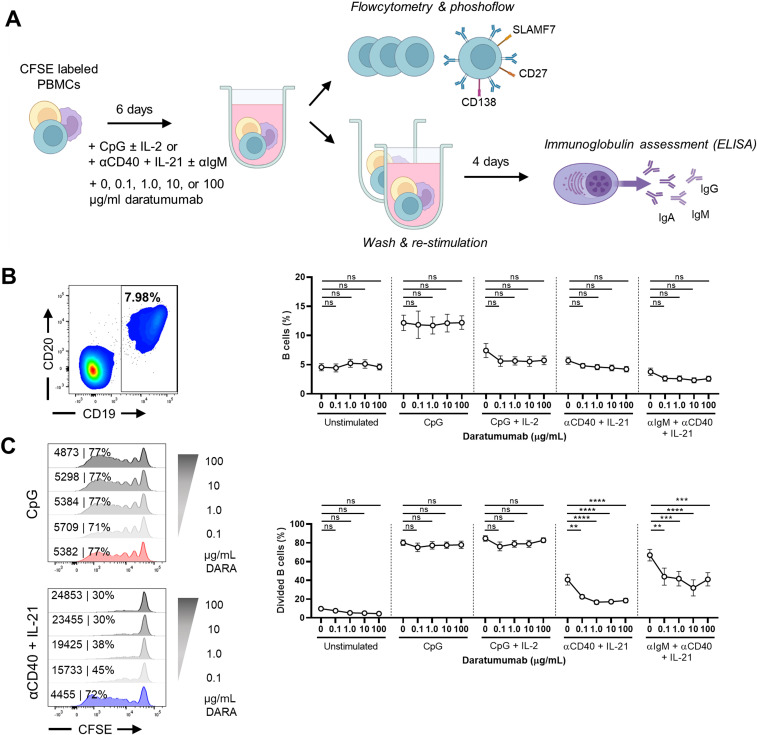

B-cell stimulation in the presence of daratumumab results in decreased B-cell proliferation upon TD stimulation

To mimic the in vivo situation in lymphoid organs where B and T cells are exposed to daratumumab (hereafter referred to as DARA), we used a previously established B-cell differentiation assay and added different concentrations of DARA (29, 30). In short, CFSE-labeled PBMCs were corrected for 25,000 B cells per well and subsequently cultured for 6 d in the presence of TI (CpG ± IL-2) or TD (αCD40 + IL-21 ± αIgM) stimuli (Fig 1A). Different concentrations DARA, for example, 0, 0.1, 1.0, 10, or 100 μg/ml, were added at the start of culture based on pharmacological in vivo studies (31). The addition of DARA did not change the percentages of B cells in the unstimulated and stimulated conditions (Figs 1B and S1A). A small decrease in total lymphocyte percentages was observed only in the conditions with 10 and 100 μg/ml DARA in the CpG + IL-2–stimulated conditions (Fig S1B). After stimulation with αCD40 + IL-21 (with and without αIgM), B cells displayed a dose-dependent decrease in proliferation in the presence of DARA (Fig 1C). Characteristically, the activation of B cells with these stimuli for 6 d results in consecutive cycles of cell division accompanied by the loss of IgD and the up-regulation of PB markers CD27 and CD38. The decrease in proliferation in the TD-stimulated conditions resulted in a significant increase in percentages of double-negative (IgD−CD27−) B cells with increasing concentrations of DARA (Fig S1C). Upon the addition of an IgG1 control antibody (anti-IgE, referred to as omalizumab [OMA]), we found no effect on B-cell proliferation after activation with TI or TD stimuli compared with the conditions where no mAb was added (Fig S2A and B). Thus, targeting CD38 with DARA reduced B-cell proliferation upon TD stimulation.

Figure 1. Characterization of an in vitro system to establish the effects of daratumumab on B-cell proliferation.

(A) Schematic overview of the experimental setup (created with BioRender.com). In short, CFSE-labeled PBMCs were cultured for 6 d without or with various concentrations of daratumumab and stimulated with CpG ± IL-2 or αCD40 + IL-21 ± αIgM. For some experiments, cells were washed at day 6 and restimulated until day 10. (B) Representative CD19/CD20 FACS plot (left) after 6 d of culture with CpG showing the gating of CD19+ B cells. Quantification (right) of the percentages CD19+ B cells (of lymphocytes) for the different conditions tested. n = 6–8. (C) Amount of proliferation by CFSE dilution. Representative histogram overlays of CD19+ B cells (left) for CpG and αCD40 + IL-21 stimulation at day 6. Values depicted next to the histograms represent the corresponding geometric MFI and the percentages of divided B cells. Quantification (right) of the percentages of divided CD19+ B cells for the different conditions tested. n = 6–8. P-values were calculated using a one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test for each condition. ns, not significant, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, and ****P ≤ 0.0001. Means ± SEM are displayed.

Figure S1. Phenotypic characterization of B-cell subsets.

(A) Gating strategy for lymphocyte and different B-cell populations. (B) Quantification of the percentages of lymphocytes for the different conditions tested. n = 6–8. (C) Quantification of the naïve (IgD+CD27−), non-switched (IgD+CD27+), switched memory (IgD−CD27+), and double-negative (IgD−CD27−) B-cell subsets in the different conditions tested. n = 6–8. P-values were calculated using a one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test for each condition. ns, not significant, *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, and ***P ≤ 0.001. Means ± SEM are displayed.

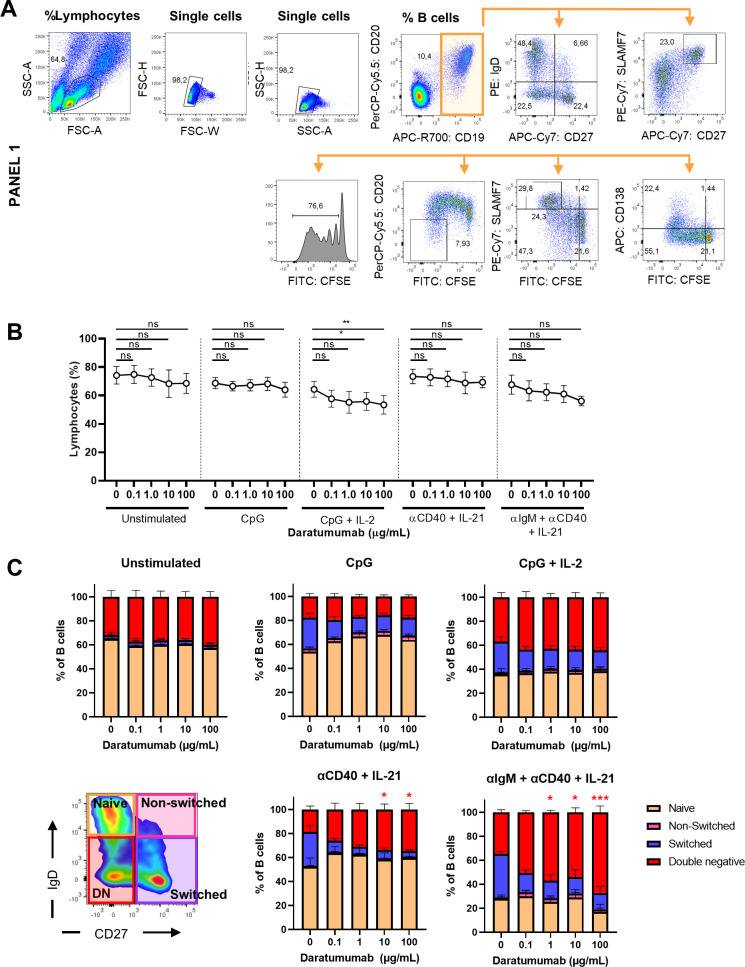

Figure S2. Effects of daratumumab and omalizumab on B-cell proliferation.

(A) Amount of proliferation by CFSE dilution. Representative histogram overlays of CD19+ B cells for CpG αIgM + αCD40 + IL-21 and αCD3 + αCD28 stimulation at day 6 with or without daratumumab (DARA; 10 μg/ml) or omalizumab (OMA; 1 and 10 μg/ml). Values depicted next to the histograms represent the corresponding geometric MFI and the percentages of divided B cells. (B) Quantification of the percentages of divided CD19+ B cells for the different conditions tested. n = 3. P-values were calculated using a two-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ns, not significant, *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, and ****P ≤ 0.0001. Means ± SEM are displayed.

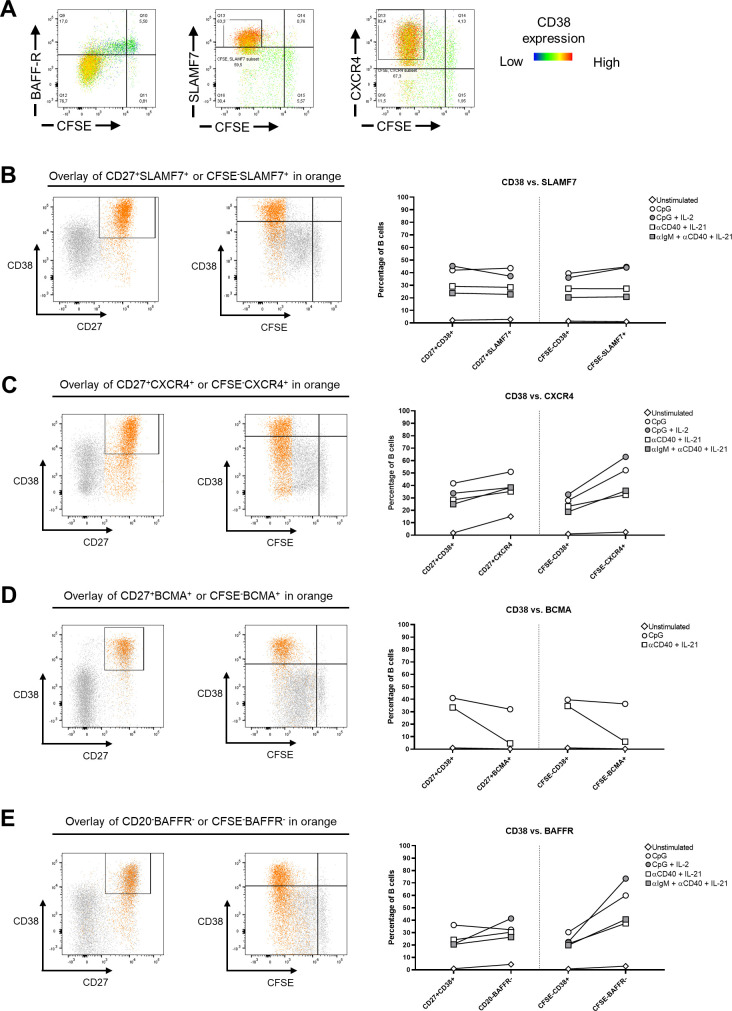

SLAMF7 suitable as a substitute for CD38 as a PB marker

Next, we studied the phenotypic and functional characteristics of B-cell differentiation. As mentioned, CD38 has extensively been used to classify PBs. Because DARA interferes with conventional fluorescently labeled anti-CD38 mAbs as a result of targeting similar epitopes, an alternative marker was required to investigate PB formation in the presence of DARA (Fig 2A) (32, 33). The up-regulation of signaling lymphocyte activation marker family member 7 (SLAMF7), C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4), and B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA), and the down-regulation of B-cell activation factor receptor (BAFFR) were identified as possible alternative extracellular markers for PB identification (34, 35, 36). Proliferating B cells (CFSElow) were BAFFR-negative, and SLAMF7- and CXCR4-positive at day 6 (Fig S3A). BCMA expression could only be detected if γ-secretase was added at the start of culture to prevent cleavage (data not shown) (37). To find a sufficient replacement for CD38 to phenotypically identify PB, the CD27+CD38+ population was compared with CD27+SLAMF7+, CD27+CXCR4+, CD27+BCMA+, and CD20−BAFFR− population after 6 d of in vitro culture. In addition, the CFSElowCD38+ population was compared with the CFSElowSLAMF7+, CFSElowCXCR4+, CFSElowBCMA+, and CFSElowBAFFR− populations (Fig S3B–E). SLAMF7 expression showed consistent similarity with CD38 expression, especially for TD stimulations (Fig S3B), whereas the other markers did not. To determine the resemblance of CD38 and SLAMF7 expression over time in the B-cell differentiation assay, the expression of CD38 and SLAMF7 was measured after 3, 4, 5, and 6 d of in vitro culture after stimulation with TD and TI stimuli. The development of PBs determined either by CD27+CD38+ or by CFSElowCD38+ compared with CD27+SLAMF7+ or CFSElowSLAMF7+ showed very similar kinetics during culture (Fig S4A and B). Thus, PBs developed over time, which is further confirmed by the gradual induction of IgG, IgA, and IgM production and release into the supernatant over time (Fig S4C). We found no up-regulation of CD38 under these stimulations in T cells (Fig S4D). In conclusion, SLAMF7 is a suitable alternative marker for CD38 in regard to B-cell differentiation. In further experiments, SLAMF7 was used to identify PBs when CD38 was insufficient to use.

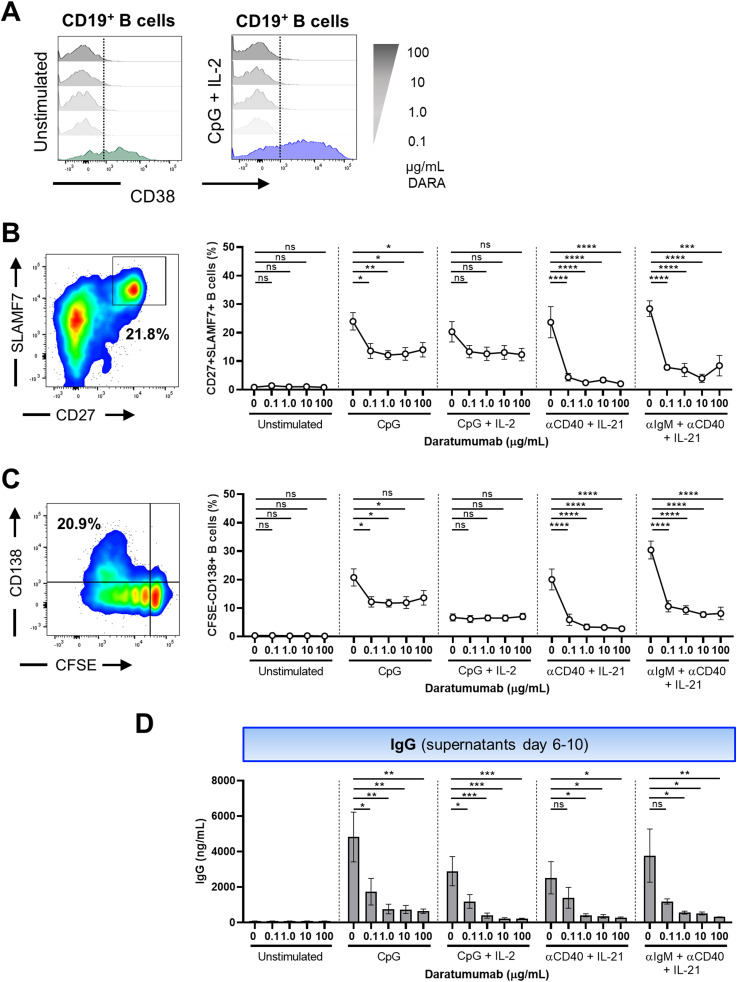

Figure 2. Effect of daratumumab on B-cell differentiation and IgG production.

(A) Representative histogram overlays of the CD38 expression of CD19+ B cells in the presence of different concentrations of daratumumab. (B, C) Representative CD27/SLAMF7 FACS plot and CFSE/CD138 FACS plot (left) showing the gating of SLAMF7+CD27+ and CFSElowCD138+ B cells within the CD19+ gate after stimulation with CpG. Quantification (right) of %SLAMF7+CD27+ and %CFSElowCD138+ B cells after 6 d of culture for the different conditions tested. n = 6–8. (D) IgG secretion measured in culture supernatants between days 6 and 10 (after washing and restimulation). n = 4. P-values were calculated using a one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test for each condition. ns, not significant, *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, and ***P ≤ 0.001. Means ± SEM are displayed.

Figure S3. SLAMF7 as an alternative for a plasmablast marker CD38.

Assessment of the expression of CD38 combined with plasmablast markers B-cell activation factor receptor (BAFFR), SLAMF7, B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA), and CXCR4 in B cells after 6 d of PBMC culture corrected for B-cell numbers with T cell–dependent (αCD40 + IL-21 and αIgM + αCD40 + IL-21) and T cell–independent (CpG and CpG + IL-2) stimulations. BCMA samples were cultured with a γ-secretase inhibitor to prevent cleavage of BCMA. (A) Representative FACS plots showing the CD38 expression overlaid on BAFFR, SLAMF7, and CXCR4 versus CFSE plots. (B, C, D, E) Representative plot overlays on the left of CpG-stimulated B cells showing (B) CD27+SLAMF7+ or CFSElowSLAMF7+, (C) CD27+CXCR4+ or CFSElowCXCR4+, (D) CD27+BCMA+ or CFSElowBCMA+, and (E) CD20−BAFFR− or CFSElowBAFFR− compared with the conventional CD27+CD38+ or CFSElowCD38+ gating strategy to identify plasmablasts and plasma cells. Plots on the right show quantification for all different stimuli tested. n = 3–4. Means are displayed.

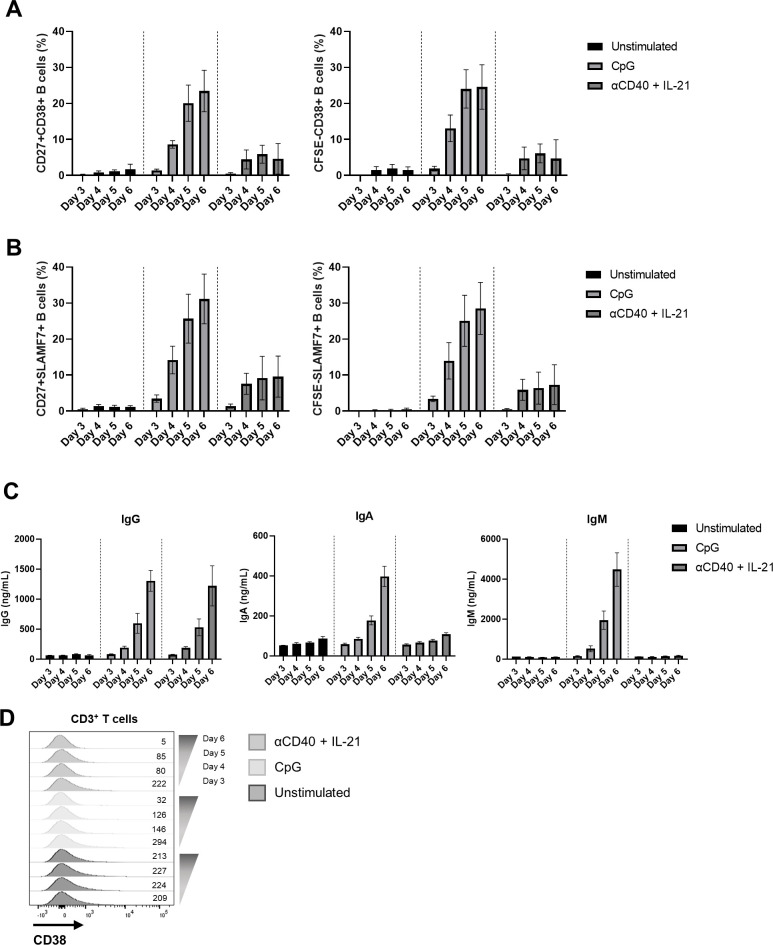

Figure S4. Timeline of CD38 and SLAMF7 up-regulation in B cells.

Expression of CD38 and SLAMF7 was determined in CD19+-gated B cells after 3, 4, 5, and 6 d of culture. Furthermore, supernatants were collected to measure the immunoglobulin production. (A) Quantification of percentages of CD27+CD38+ (left) and CFSElowCD38+ (right) B cells. (B) Percentages of CD27+SLAMF7+ (left) and CFSElowSLAMF7+ (right) B cells. (C) Secreted IgG, IgA, and IgM in cultured supernatants. n = 4. Means ± SEM are displayed. (D) Representative plot overlays of CD38 expression in CD3+ T cells after 3, 4, 5, and 6 d of stimulation.

Daratumumab limits in vitro B-cell differentiation and IgG production

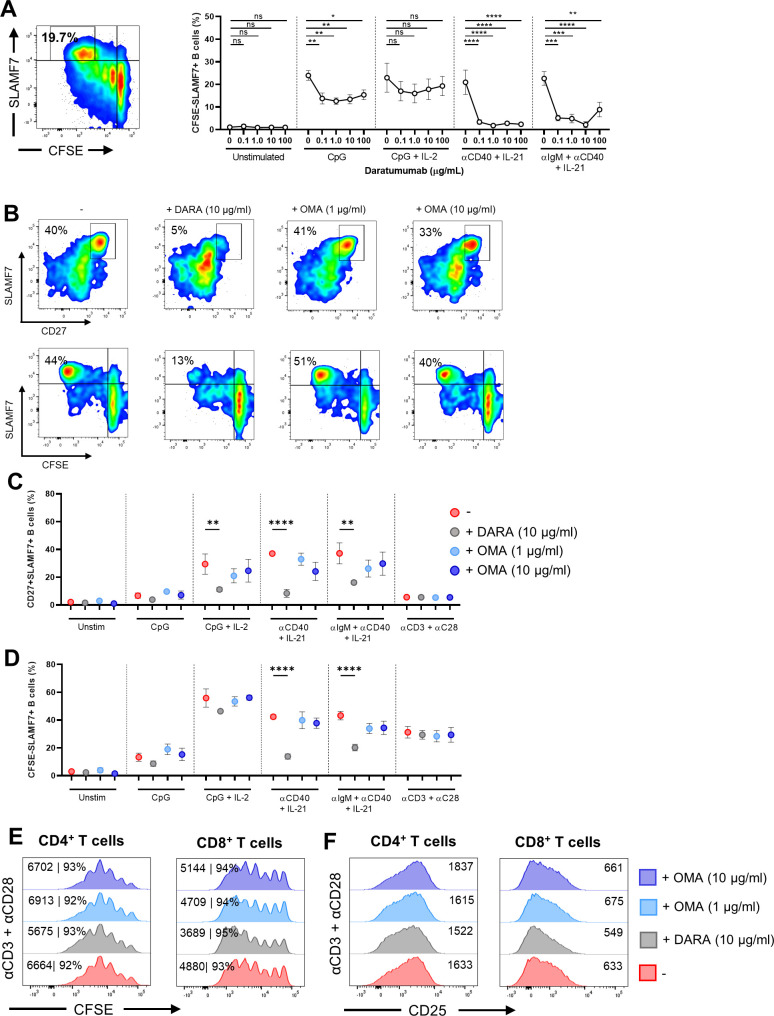

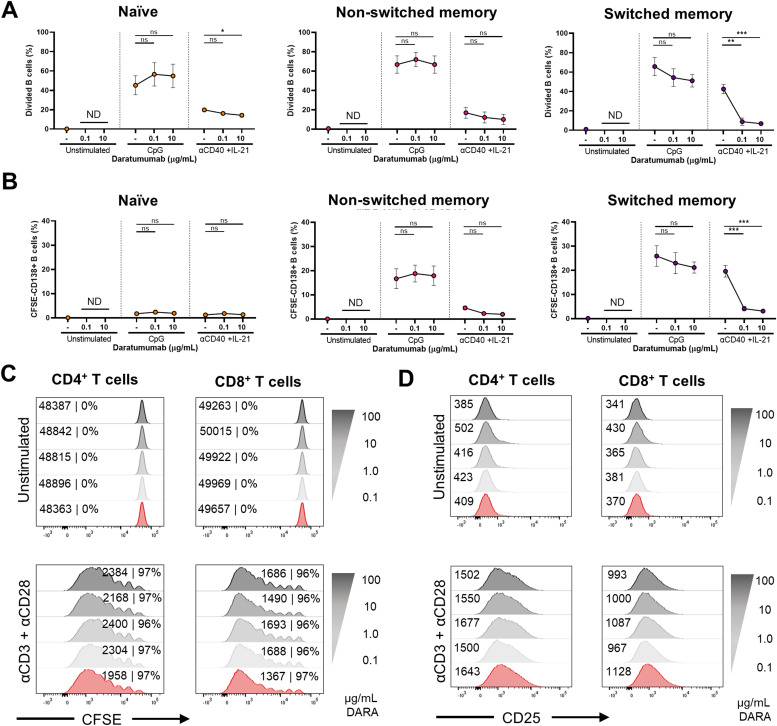

To assess the effect of DARA on B-cell differentiation, we analyzed the formation of PBs (CD27+SLAMF7+, CFSElowSLAMF7+) and PCs (CFSElowCD138+) after 6 d of culture and supernatants were collected to measure immunoglobulin production. Dose–response kinetics revealed >50% decrease in the percentages of CD27+SLAMF7+ and CFSElowSLAMF7+ PBs and CFSElowCD138+ PCs already in the presence of the lowest concentration of DARA in the cultures stimulated with CpG, αCD40 + IL-21, and αIgM + αCD40 + IL-21 (Figs 2B and C and S5A). When PBMCs were cultured in the presence of the IgG1 control antibody OMA, no significant effect was found on CD27+SLAMF7+ and CFSElowSLAMF7+ PB formation (Fig S5B and C). In addition, DARA and OMA showed no effect on the proliferation and up-regulation of the activation marker CD25 upon stimulation with αCD3 + αCD28 measured in the CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Fig S5E and F). The exact measurement of IgG secretion in these culture supernatants was challenging, because DARA is a human IgG and interferes with the IgG ELISA (data not shown) (38). Therefore, PBMCs that were cultured with DARA for 6 d were washed and then restimulated in fresh medium with the same combination of stimuli for another 4 d. Supernatants of the additional 4-d culture (days 6–10) were collected and analyzed. Interestingly, we found a significant reduction in IgG production when B cells were exposed to different concentrations of DARA in all conditions tested preceding the restimulation (Fig 2D). No significant effect of DARA on IgA and IgM secretion could be detected in the culture supernatants between days 0 and 6 and between days 6 and 10 (Fig S6A–D). Overall, these results suggest that targeting CD38 with DARA has an effect on B-cell differentiation and IgG production using TI and TD stimuli, whereas it did not affect T-cell proliferation or activation present in these cultures.

Figure S5. Effects of daratumumab and omalizumab on B-cell differentiation and T-cell activation.

(A) Representative CFSE/SLAMF7 FACS plot (left panel) showing the gating of CFSElowSLAMF7+ B cells within the CD19+ gate after stimulation with CpG. Quantification (right panel) of %CFSElowSLAMF7+ B cells after 6 d of culture. n = 6–8. P-values were calculated using a one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test for each condition. (B) Representative CD27/SLAMF7 (upper panels) and CFSE/SLAMF7 (lower panels) FACS plots (left panel) showing B-cell differentiation of CD19+ B cells after αCD40 + IL-21 stimulation after 6 d of culture with or without daratumumab (DARA; 10 μg/ml) or omalizumab (OMA; 1 and 10 μg/ml) n = 3. (C, D) Quantification of %SLAMF7+CD27+ and %CFSElowSLAMF7+ B cells after 6 d of culture for the different conditions tested. n = 3. (E, F) Representative histogram overlays of CFSE dilution and CD25 up-regulation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells at day 6 after αCD3 + αCD28 stimulation. Values depicted next to the histograms represent the corresponding percentages of divided CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and/or geometric MFI, respectively. n = 3. P-values were calculated using a two-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ns, not significant, *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, and ****P ≤ 0.0001. Means ± SEM are displayed.

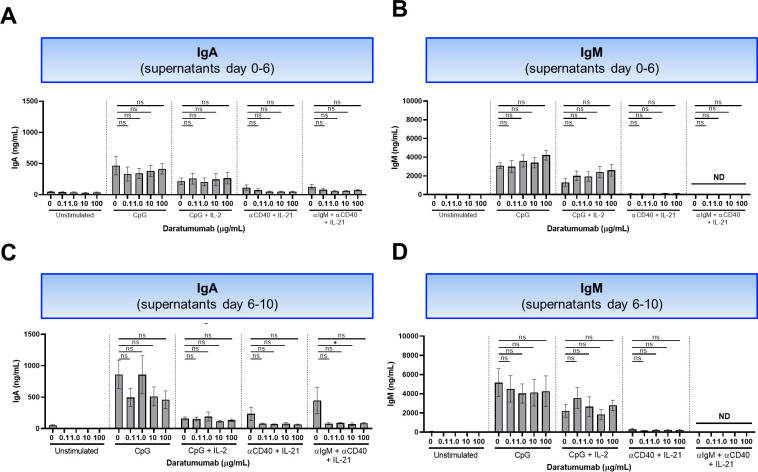

Figure S6. Effect of daratumumab on IgA and IgM production.

(A, B) Secreted IgA and IgM in culture supernatants between days 0 and 6. n = 6–8. (C, D) Secreted IgA and IgM measured in culture supernatants between days 6 and 10 (after washing and restimulation). n = 4. P-values were calculated using a one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test for each condition. ns, not significant, *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, and ****P ≤ 0.0001. Means ± SEM are displayed.

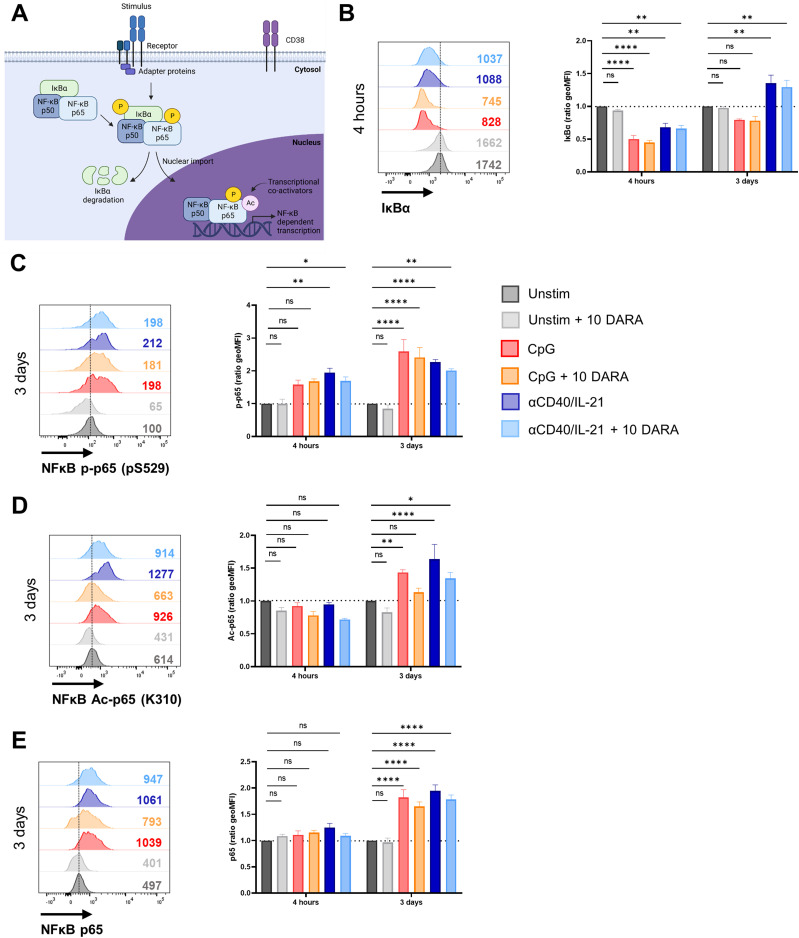

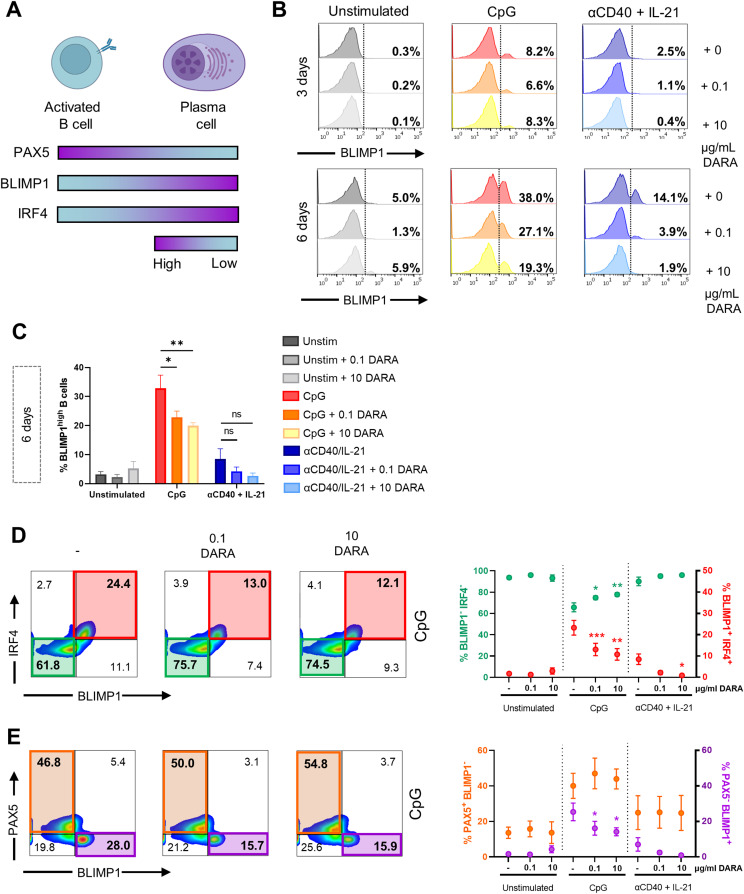

Daratumumab attenuates activation-induced phosphorylation and acetylation of NF-κB in B cells

The extent of B-cell differentiation is regulated by a complex interplay of signaling pathways and transcription factors (TFs) (1). The canonical and non-canonical NF-κB pathway has been shown to play a critical role in B-cell development, activation, and survival (39). Classical NF-κB activation results after stimulus-coupled phosphorylation of cytoplasmic IκBα inhibitors by IκB kinases. These IκBα inhibitors are degraded by the proteasome allowing p50/p65 NF-κB complexes to enter the nucleus and stimulate target gene expression (40). For the full transcriptional activity of p65, it has been previously shown that phosphorylation at serine 529/536 and acetylation at lysine 310 of p65 are key post-translational modifications needed for the full transcriptional activity of NF-κB (Fig 3A) (41, 42, 43). The constitutive activation of p65 and the subsequent expression of target genes including BLIMP1 can drive PC formation. In an attempt to identify cellular processes affected by DARA treatment, we investigated the effect of DARA on p65 using phosphoflow cytometry (44). B cells were cultured with TI or TD stimuli in the absence or presence of DARA (10 μg/ml) and analyzed after 4 h or 3 d, as these time points were the most effective for tracking signaling events by phosphorylation and acetylation of NF-κB (44). To accommodate the differences in fluorescence intensity between donors, the ratio of unstimulated to stimulated B cells was calculated by normalizing to the expression in unstimulated (without DARA) B cells (set at a value of 1). Upon activation with TI or TD stimuli, we observed the reduced expression of IκBα in B cells already after 4 h of stimulation, but not in T cells, suggesting successful stimulus-coupled degradation of IκBα (Figs 3B and S7A and B). DARA treatment did not affect IκBα degradation or re-expression. At both time points, we also observed the increased expression of phosphorylated p-65 (p-p65), whereas after 3 d of stimulation, acetylated-p65 (Ac-p56) could be observed in B cells (Figs 3C and D and S7C and D). Interestingly, DARA treatment lowered the ratio of p-p65 induction upon TD stimulation and the ratio of Ac-p65 induction upon TI and TD stimulation after 3 d of culture. Total p65 protein levels were up-regulated after 3 d of stimulation, but remained unaffected by DARA treatment (Figs 3E and S7E). In the same experiments, DARA treatment had no effect on NF-κB protein levels and modifications in T cells (Fig S7B–E), coinciding with the lack of CD38 up-regulation observed upon these B cell–specific stimulations (Fig S4D). We found no effect of DARA on phosphorylation of ERK 1/2, downstream of the BCR and TLR9, or phosphorylated or total levels of STAT3, downstream of the IL-21 receptor (Fig S8A–C). In addition, we measured the expression of PAX5, BLIMP1, and IRF4 as indicators for their transcriptional status. Generally, strong NF-κB signaling allows up-regulation of IRF4 and the expression of BLIMP1 while down-regulating PAX5, together resulting in PC differentiation (Fig 4A) (4, 5). B cells were stimulated as above in the absence or presence of two concentrations of DARA (0.1 and 10 μg/ml). B cells were analyzed on days 3 and 6, as these time points were the most effective for tracking the induction of differentiation as we have shown that CD27+SLAMF7+ PBs can be detected from day 3 onward using these stimuli (Fig S4). BLIMP1 expression analysis showed the expected increase in the percentage of BLIMP1high B cells over time upon CpG or αCD40 + IL-21 stimulation, and there was a downward trend upon the addition of different concentrations of DARA (Figs 4B and C and S8D). To examine the TF profile at day 6, the co-expression of these TFs was analyzed. Upon DARA treatment, >50% reduction in BLIMP1+IRF4+ B cells was observed in the CpG-stimulated conditions, with an expected increase in BLIMP1−IRF4− B cells (Fig 4D). In addition, in the same conditions we found a small reduction in BLIMP1+PAX5− B cells but, surprisingly, without an increase in the PAX5+BLIMP1− B cells (Fig 4E). This indicates that DARA attenuates activation-induced phosphorylation and acetylation of NF-κB in B cells, which would normally lead to gene transcription and the up-regulation of BLIMP1.

Figure 3. Daratumumab attenuates activation-induced phosphorylation and acetylation of NF-κB in B cells.

(A) Schematic representation of phosphorylation and acetylation events of NF-κB proteins upon stimulation. (B) Representative histogram overlays (left) of the IκBα expression of CD19+ B cells after 4 h of stimulation with indicated stimuli ± 10 μg/ml daratumumab. The geometric mean (geoMFI) ratio (right) was calculated by normalizing to the expression in unstimulated CD19+ B cells (set at a value of 1) at the corresponding time point. n = 3. (C, D, E) Representative histogram overlays (left) of (C) NF-κB phospho-p65 (pS529), (D) NF-κB acetylated-p65 (K310), and (E) NF-κB total-p65 and expression of CD19+ B cells after 3 d of stimulation with indicated stimuli ± 10 μg/ml daratumumab. The geometric mean (geoMFI) ratio (right) was calculated by normalizing to the expression in unstimulated CD19+ B cells (set at a value of 1) at the corresponding time point. n = 3. P-values were calculated using a two-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ns, not significant, *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, and ****P ≤ 0.0001. Means ± SEM are displayed.

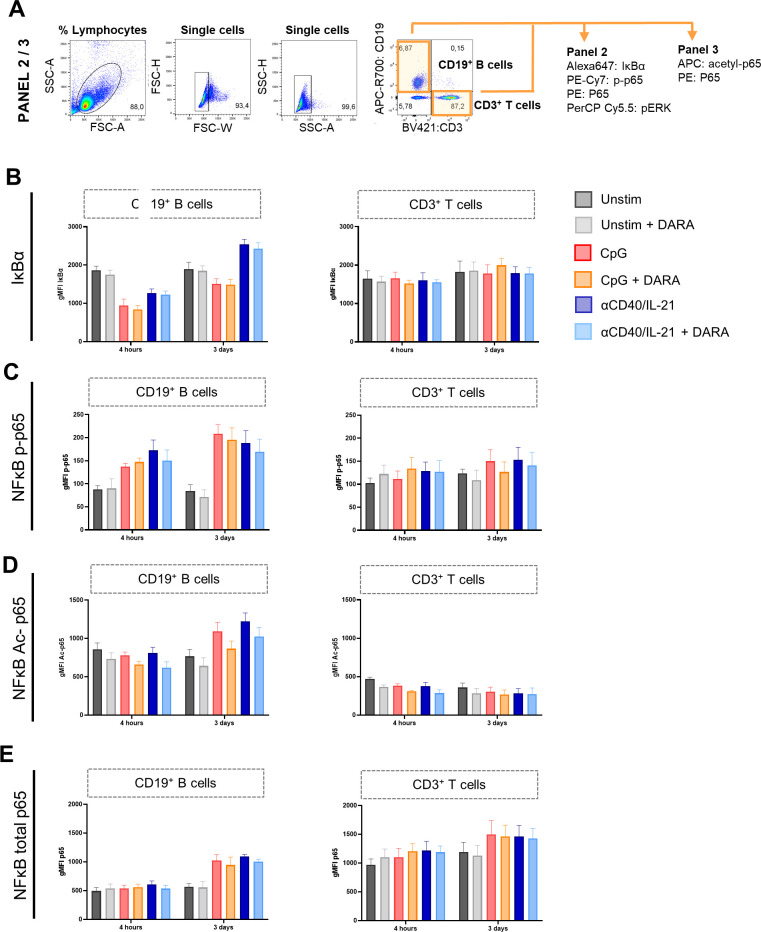

Figure S7. Effects of daratumumab on activation of canonical NF-κB proteins in B and T cells.

(A) Gating strategy for B- and T-cell populations. (B, C, D, E) Geometric MFI of CD19+ B cells (left) and CD3+ T cells (right) of (B) IκBα, (C) NF-κB phospho-p65 (pS529), (D) NF-κB acetylated-p65 (K310), and (E) NF-κB total-p65 expression after 4 h and 3 d of culture with indicated stimuli ± 10 μg/ml daratumumab. n = 3. Means ± SEM are displayed.

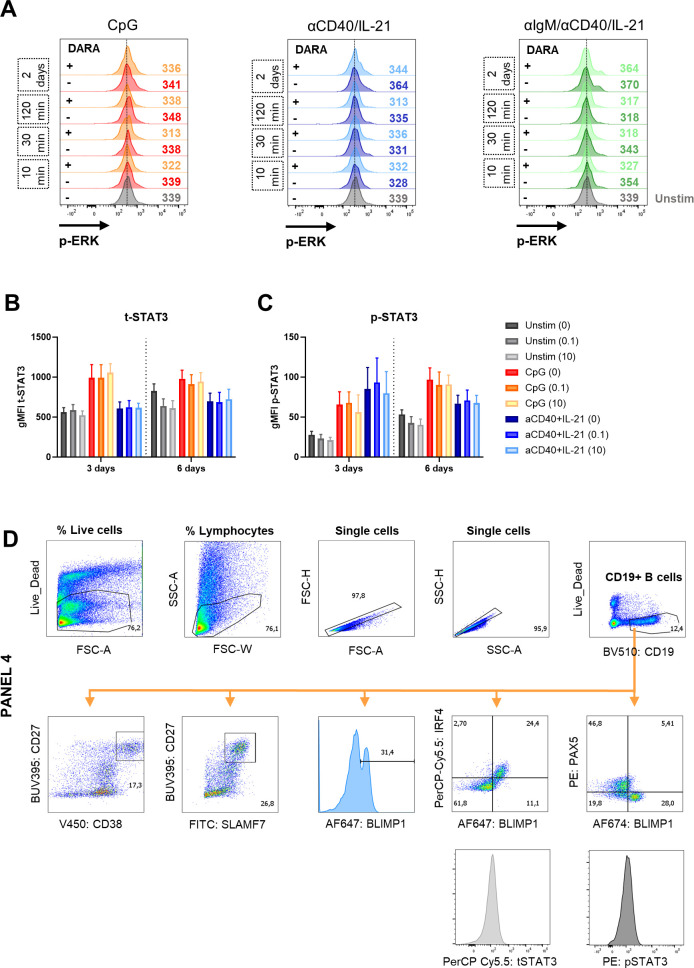

Figure S8. Effects of daratumumab on signaling molecules and transcription factors in B cells.

(A) Histogram overlays of pERK expression after 10, 30, and 120 min, and 2 d of culture without stimulation (unstim) or indicated stimuli with or without daratumumab (1.0 μg/ml). One representative donor is shown of n = 2–4. (B, C) Geometric MFI of CD19+ B cells of total-STAT3 and p-STAT3 (pY705) expression after 3 and 6 d of culture with indicated stimuli and daratumumab (0.1 or 10 μg/ml). n = 3. (D) Gating strategy for B-cell populations and transcription factor expression.

Figure 4. Effects of daratumumab on B-cell transcription factors during differentiation.

(A) Schematic representation of the expression of transcription factors PAX5, BLIMP1, and IRF4 during B-cell activation and differentiation (created with BioRender.com). (B) Representative histogram overlays of the BLIMP1 expression of CD19+ B cells after 3 and 6 d of stimulation with indicated stimuli and daratumumab (0.1 or 10 μg/ml). (C) Quantification of the percentages of BLIMP1high B cells at day 6 for the different conditions tested. n = 3. (D) Representative BLIMP1/IRF4 FACS plots (left) showing the gating of BLIMP1−IRF4− and BLIMP1+IRF4+ within the CD19+ gate after stimulation with CpG. Quantification (right) of %BLIMP1−IRF4− (green) and %BLIMP1+IRF4+ (red) B cells after 6 d of culture for the different conditions tested. n = 3. (E) Representative BLIMP1/PAX5 FACS plots (left) showing the gating of PAX5+BLIMP1− and PAX5−BLIMP1+ within the CD19+ gate after stimulation with CpG. Quantification (right) of %PAX5+BLIMP1− (orange) and %PAX5−BLIMP1+ (purple) B cells after 6 d of culture for the different conditions tested. n = 3. P-values were calculated using a two-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ns, not significant, *P ≤ 0.05, and **P ≤ 0.01. Means ± SEM are displayed.

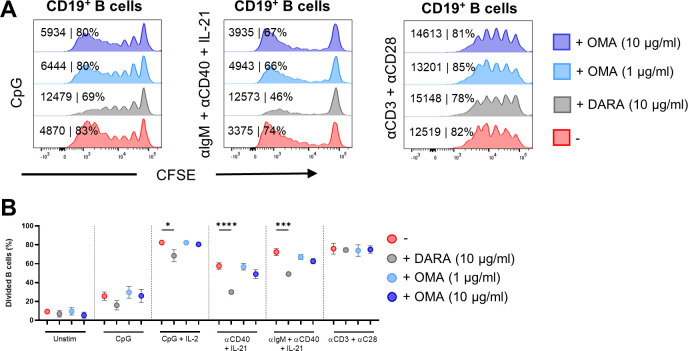

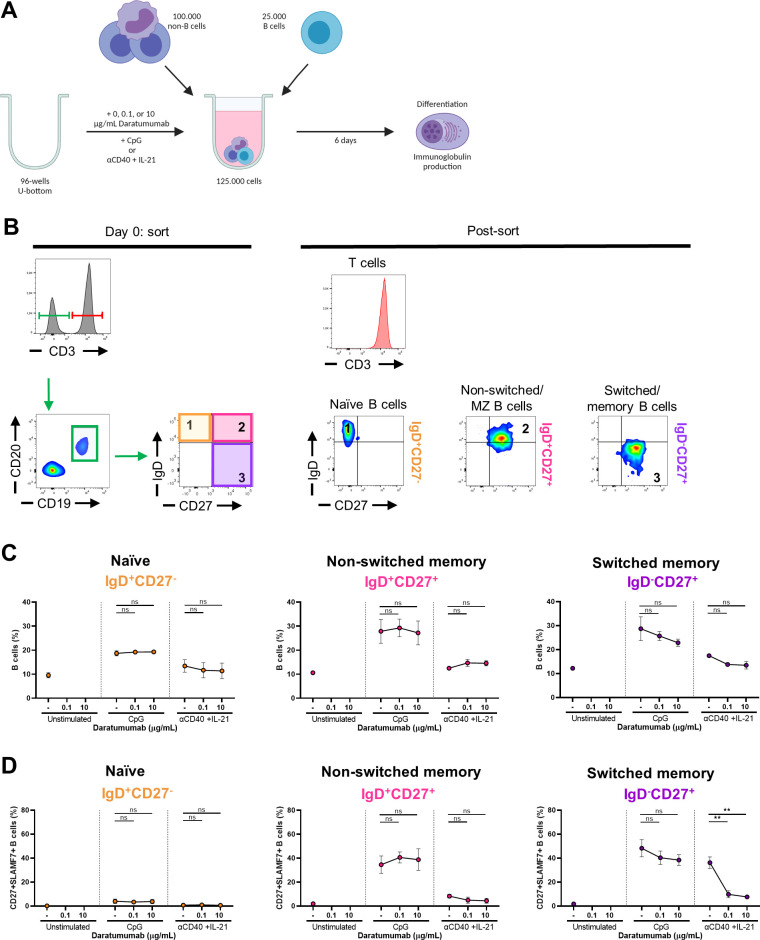

Daratumumab inhibits the proliferation and differentiation of sorted CD19+IgD−CD27+ memory B cells but not T cells

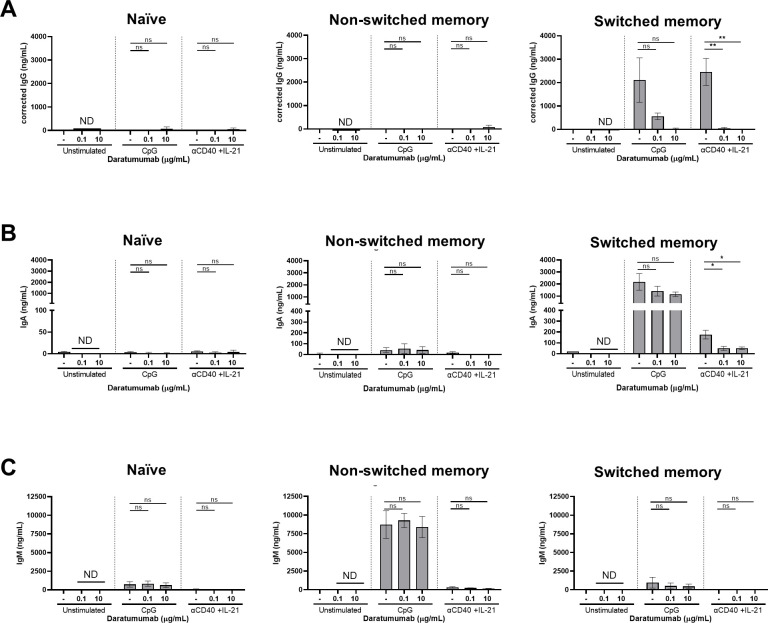

Because the starting population of B cells comprises both naïve, non-switched, and switched memory B cells, we investigated which of these subsets was most affected by DARA. FACS-sorted naïve (CD19+IgD+CD27−), non-switched memory (CD19+IgD+CD27+), and switched memory (CD19+IgD−CD27+) B-cell populations with the addition of autologous non-B cells (mostly T cells) were cultured with or without DARA and stimulated with CpG or αCD40 + IL-21 for 6 d (Fig S9A and B). In this system, sorted switched memory B cells generally differentiate stronger to TI and TD stimulation than the naïve and non-switched B cells (Fig 5B). Again, we found no effect of DARA on the B-cell percentages using the sorted B-cell fractions (Fig S9C). The addition of DARA caused significantly reduced proliferation and differentiation of memory B cells with αCD40 + IL-21 (Figs 5A and B and S9D), while only showing a non-significant trend upon CpG stimulation. Lastly, immunoglobulin production of the memory B-cell fraction stimulated with αCD40 + IL-21 showed a significant decrease in IgG and IgA, but not IgM production (being hardly detectable at all under these conditions) (Fig S10A–C). Because of the previously mentioned interference of DARA with the IgG ELISA, we report here an estimated-IgG production where the levels were corrected for DARA present in the culture supernatant. Naïve B cells produced low amounts of IgM independently of DARA treatment, whereas non-switched B cells produced large quantities of IgM and low quantities of IgA independent of treatment with DARA. Unlike B cells, activation and proliferation of sorted CD3+ T cells were not affected by DARA upon αCD3 + αCD28 stimulation determined by the CFSE dilution and an increase in the CD25 expression of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Fig 5C and D). In sum, primarily memory B cells stimulated with αCD40 + IL-21 were affected by DARA.

Figure S9. Effects of daratumumab on sorted naïve and memory B-cell subsets and T cells.

(A) Schematic overview of the experimental setup (created with BioRender.com). In short, CFSE-labeled PBMCs were sorted on day 0. 25,000 FACS-sorted naïve (CD19+IgD+CD27−), non-switched (CD19+IgD+CD27+), and memory (CD19+IgD−CD27+) B-cell populations were co-cultured with 100,000 autologous non-B cells and DARA (0.1 and 10 μg/ml) for 6 d. FACS-sorted CD3+ T cells were cultured with five different concentrations of DARA with αCD3+αCD28 for 6 d. (B) Gating strategy used for sorting on day 0 (on the left) and purity stains after sorting (on the right). (C) B-cell percentages of cultured IgD+CD27−, IgD+CD27+, and IgD−CD27+ B cells. (D) Differentiation of cultured IgD+CD27−, IgD+CD27+, and IgD−CD27+ B cells determined by CD27+SLAMF7+ B cells. n = 3. P-values were calculated using a two-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ns, not significant and **P ≤ 0.01. Means ± SEM are displayed.

Figure 5. Effects of daratumumab on sorted naïve and memory B-cell subsets and T cells.

(A, B) FACS-sorted naïve (CD19+IgD+CD27−), non-switched (CD19+IgD+CD27+), and memory (CD19+IgD−CD27+) B-cell populations were co-cultured with autologous non-B cells with CpG or αCD40 + IL-21 and daratumumab (0.1 or 10 μg/ml) for 6 d. (A, B) Quantification of the percentages of (A) divided and (B) CFSE−CD138+ B cells at day 6. n = 3. (C, D) FACS-sorted CD3+ T cells were cultured with αCD3+αCD28 and five different concentrations of daratumumab for 6 d. (C, D) Amount of proliferation by CFSE dilution and (D) amount of activation by CD25 up-regulation. Representative histogram overlays of CD4+ (left) and CD8+ (right) T cells at day 6 after no stimulation or αCD3 + αCD28. Values depicted next to the histograms represent the corresponding geometric MFI and the percentages of divided CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, respectively. n = 3. P-values were calculated using a two-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ns, not significant, *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, and ***P ≤ 0.001. Means ± SEM are displayed.

Figure S10. Effects of daratumumab on IgG, IgA, and IgM production of sorted naïve and memory B-cell subsets.

(A, B, C) Secreted (A) IgG, (B) IgA, and (C) IgM in culture supernatants between days 0 and 6 of sorted naïve (IgD+CD27−), non-switched (IgD+CD27+), and switched (IgD−CD27+) B cells. IgG concentrations were corrected for the presence of DARA in the supernatant. n = 3. P-values were calculated using a two-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ns, not significant, *P ≤ 0.05, and **P ≤ 0.01. Means ± SEM are displayed.

Discussion

CD38 is a glycoprotein found on the surface of many (activated) immune cells, including CD4+, CD8+, B lymphocytes, and natural killer cells (45). Expression is highest on PBs and PCs, and the malignant counterpart in MM (46). Apart from its approval for MM treatment, CD38-targeting mAb DARA is gaining attraction as a rescue therapy for autoimmune conditions with PC involvement (Table S1). Hitherto, the promising evidence for DARA as a therapeutic option in autoimmune diseases is based exclusively on individual case reports (47). How anti-CD38 therapy influences normal PCs or PC differentiation beyond depletion in cancer settings has remained virtually unexplored. In this study, we observed profound differences in B-cell proliferation, differentiation, and immunoglobulin production under DARA treatment in vitro at very low doses already. Mechanistically, we show that DARA influences the induction of differentiation-associated signaling and TF levels in B cells. Furthermore, our data imply that the presence of DARA most prominently leads to inhibition of the switched memory B-cell responses, which could be beneficial in an autoimmune setting but disadvantageous upon infection or in vaccination strategies.

Upon the addition of DARA, the CD38 expression on B cells was unmeasurable with fluorescently labeled mAbs, which was reported previously as well (34). The suitability of the surface expression of SLAMF7 for the identification of PBs in peripheral blood confirms previous studies for bone marrow samples (34, 48). Proliferation of B cells only showed a significant decrease in αCD40 + IL-21 (±αIgM)– and not CpG-stimulated conditions, indicating that TLR9 stimulation seems independent of any CD38 influence in B-cell activation. In a recent study, human peripheral B cells were stimulated with Fab fragments (αIgM/G/A) + CpG + IL-2 in the presence of α-CD38 mAbs (clone HB-7 and DARA) showing reduced proliferation after 5 and 7 d (28), which was suggested to be causally explained by pERK protein expression at early time points in B cells pretreated with DARA (within 1 h). We were unable to confirm the effect of DARA on early ERK phosphorylation in our cultures. Although the combination of stimuli and the setup of experiments (short and long stimulations) differ from our study (28), collectively these data suggest that DARA inhibits B-cell proliferation upon either BCR or CD40, but not TLR9 stimulation, coinciding with perturbations in protein phosphorylation and acetylation.

In our 6-d B-cell differentiation assay, we observed an effect of DARA on B-cell differentiation and IgG production irrespective of TD or TI stimulation. For elucidation of cues promoting B-cell differentiation into PCs, here it is important to highlight that naïve (IgD+CD27−), non-switched memory (IgD+CD27+), and switched memory (IgD−CD27+) B cells react differently upon TD and TI signals. When total B cells are stimulated with CpG, B cells differentiate into CD27+SLAMF7+ PBs and secrete IgG, IgA, and IgM immunoglobulins. We show that stimulation of total B cells with CpG essentially measures the function of switched memory B cells (29), as they produce the vast majority of IgG and IgA, whereas the non-switched memory B cells produce large quantities of IgM in vitro. The production of IgM was not reduced in both purified and non-purified cultures, indicating that the non-switched B-cell populations were unaffected. Upon CpG stimulation, a consistent trend was observed in reduced differentiation and IgG production upon CpG stimulation, either in the total B-cell or in the sorted B-cell subset cultures. In addition, we found reduced PCs upon stimulation both on phenotypic and on transcriptional levels. An important finding was that the proliferation, differentiation, and IgG production upon TD stimulation with αCD40 + IL-21 were strongly inhibited by DARA, coinciding with reduced activation of NF-κB and PC TF expression. Moreover, IgA and IgG production by sorted memory B cells stimulated with αCD40 + IL-21 was strongly reduced at very low concentrations. A preceding in vivo study regarding the pharmacokinetics of DARA showed a serum concentration 10- to 100-fold higher than the active concentrations used in this study for several months (49). Although T cells express CD38 upon activation (45), both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell activation and proliferation were not affected by DARA upon T-cell stimulation with αCD3/CD28.

The strength of this study is that we have investigated both TD and TI B-cell responses in the presence of DARA with a strong impact on TD stimulation and—in this respect—a differential outcome of different B-cell subsets, demonstrating the most impact of CD38 targeting on the activation and maturation of memory B cells into PBs and PCs. Although derived from an in vitro system, our findings do suggest a possible mechanism for the additional risk of bacterial and viral infections in MM patients receiving anti-CD38–directed therapies in vivo (50, 51). Where normally the barrier of immunological memory would protect patients, reduced recall responses by memory B cells upon TI or TD stimulation leave patients who receive DARA treatment prone to infections with common pathogens (16). As mentioned previously, patients treated thus far with DARA show reduced humoral responses to anti-SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccinations (52, 53, 54, 55), although this negative impact on vaccinations was less obvious in other studies (40, 56). Although these mixed observations suggest that DARA treatment may negatively affect humoral responses in the context of vaccination, this needs further confirmation. Our data showed that T-cell activation was not affected by DARA treatment, suggesting that cellular responses by T cells would not be affected by DARA treatment after vaccination and would therefore provide additional protection.

Although the mode of action remains to be fully explained, there are several explanations possible. First, targeting CD38 with an antibody or removing this molecule with CRISPR/Cas9 has been reported to inhibit the association of CD19 with the IgM-BCR, directly impairing BCR signaling in normal and malignant B cells (28). Our data that DARA had little if any effect with naïve and non-switched memory B cells upon BCR stimulation are not easily reconciled with this explanation as the only mode of action. Alternatively, CD38 acts as a receptor and an ectoenzyme (45) and gained appreciation as an immune metabolic modulator in multiple immune cells (57, 58, 59). The enzymatic functions attributed to CD38 are primarily investigated in mouse and tumor models (16, 60). Clinical relevance is sought in the relationship between the membrane expression of CD38 and the extracellular and cytoplasmic NAD+ levels. Engagement of CD38 using mAbs such as daratumumab or isatuximab would block the enzymatic activities (61), further supported by in vitro studies with MM cell lines (62). In the extracellular compartment, it would potentially contribute to the generation of adenosine monophosphate and adenosine by the ectoenzyme CD38/CD203a/CD73 pathway, which would then suppress B and T cells (60, 63, 64). Although not excluded at the biochemical levels, in our studies DARA did not inhibit T-cell activation indicating a differential effect if present. In the intracellular compartment, increased NAD+ levels could influence the subsequent activity of several NAD+-consuming enzymes, which could play a role in orchestrating fate decisions, in particular in those cells with increased expression levels such as PCs (60). Key NAD+-consuming enzymes are poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1/2 (PARP-1/2) and the family of sirtuins (SIRTs), which play important roles in cell death, aging, and metabolic regulation of immune cell function (65, 66), including B cells (65, 67). More importantly, these proteins can modulate transcriptional co-activators and thereby influence TF activity. In knockout mice, CD38 deficiency has been associated with increased activation of the NAD-dependent deacetylating enzyme SIRT1 (24, 25), which also deacetylates acetyllysine in selected proteins involved in DNA transcription. By deacetylating NF-κB p65 at lysine 310, SIRT1 also inactivates NF-κB (25). This may correspond to the role of SIRT1 to modulate activation-induced cytidine deaminase (gene symbol AICDA, protein abbreviated AID) expression, a protein involved in class-switch recombination, and the antibody response in human B cells (68). These data would match the lack of an inhibitory effect of DARA on non-switched IgM-producing B cells shown here. Our demonstration of reduced phosphorylation and acetylation of NF-κB through direct or indirect effects of DARA on CD38 function during stimulation would outline a possible mechanism by which the full transcriptional activity of NF-κB is abolished, resulting in less PB and PC formation and IgG secretion in vitro.

In conclusion, our study has identified a mechanism to explain why MM patients receiving DARA show reduced autoantibody levels, lower vaccination responses, and increased infection risks (12, 15, 69). We showed that DARA inhibits proliferation and differentiation of B cells into PBs and PCs, although the function of CD38 needs to be elucidated to obtain further knowledge about the exact mechanism of action of DARA. With the expected increase in the use of DARA therapeutically and current knowledge, it would be reasonable to consider infectious prophylaxis in patients receiving DARA to counteract the possible increased risk of infections and/or vaccine failures.

Materials and Methods

Samples

PBMCs were derived from buffy coats from healthy donors. All the healthy donors provided written informed consent in accordance with the protocol of the local institutional review board, the Medical Ethics Committee of Sanquin Blood Supply, and the study conformed to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. PBMCs were isolated using density gradient centrifugation with Lymphoprep (Serumwerk Bernburg). After isolation, PBMCs were cryopreserved and stored in liquid nitrogen until further use.

Human B-cell cultures and proliferation assay

First, PBMCs were thawed and resuspended in PBS at a concentration of 5–10 × 106 cells/ml. Cells were labeled with 0.5 μM CFSE (FITC; Molecular Probes) for 12 min at 37°C under constant agitation. The labeled PBMCs were washed with PBS and resuspended in IMDM supplemented with 10% FCS (BioWhittaker), 0.05 mg/ml gentamicin (Gibco), and 3.6 × 10−4% v/v β-mercaptoethanol (Merck). CFSE-labeled PBMCs containing a fixed number of 2.5 × 104 B cells were cultured in 96-well U-bottom plates for 4 h, 3 d, or 6 d at 37°C and stimulated with 1 μg/ml CpG oligodeoxynucleotide 2006 (InvivoGen) ± 100 U/ml IL-2 (R&D Systems), or with 1 μg/ml αCD40 mAb (clone 14G7; Sanquin) and 20 ng/ml IL-21 (Invitrogen) ± 5 μg/ml αIgM mAb (clone MH15; Sanquin). For T-cell stimulation, cells were stimulated with saturating amounts of soluble αCD3 (clone 1xE) and αCD28 (cone 15E8). PBMCs were cultured in the presence of various concentrations of daratumumab (Darzalex; Janssen Pharmaceuticals) (0, 0.1, 1.0, 10, or 100 μg/ml). In some experiments, PBMCs were cultured with various concentrations of mAb OMA (anti-IgE, human IgG1 kappa; Novartis) (1.0 or 10 μg/ml). For specific experiments that required analysis of BCMA, samples were cultured with 100 nM γ-secretase inhibitor to prevent cleavage of BCMA. Supernatants were collected for further analysis. To obtain supernatants that did not contain daratumumab, in specific experiments, cells were washed after day 6 and restimulated for 4 d with stimuli as described above, after which supernatants were collected.

Flow cytometry

Extracellular staining of surface markers

PBMCs were resuspended in PBS supplemented with 0.5% wt/vol BSA, 2 mM EDTA, and 0.01% sodium azide and incubated with saturating concentrations of fluorescently labeled conjugated mAbs for 30 min at 4°C under constant agitation as described before (29). Cells were analyzed using a FACSCanto II flow cytometer and FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences). Using FlowJo software, proliferation of B and T cells was determined by measuring CFSE dilution, whereas activation and differentiation were assessed by the expression of CD25, CD27, CD38, CD138, and SLAMF7. The following mAbs (indicated as panel 1) were used for immunophenotyping: CD3 APC-R700 (557943; BD Biosciences), CD4 PE-Cy7 (348809; BD Biosciences), CD8 PerCP-Cy5.5 (341050; BD Biosciences), CD19 APC-R700 (564977; BD Biosciences), CD20 PerCP-Cy5.5 (332781; BD Biosciences), CD25 APC (340907; BD Biosciences), CD27 APC (337169; BD Biosciences), CD27 APC-eFluor 780 (47-0279-42; eBioscience), CD38 PE (345806; BD Biosciences), CD38 PE-Cy7 (335825; BD Biosciences), CD138 APC (347216; BD Biosciences), BAFFR APC (316916; BioLegend), BCMA PE (357504; BioLegend), CXCR4 PE-Cy7 (306514; BioLegend), IgD PE (555779; BD Biosciences), and SLAMF7 PE-Cy7 (331815; BioLegend).

Intracellular staining of signaling and TFs

Cells were harvested, pooled, and pelleted before washing twice with 10 ml of PBS/0.1% BSA. Next, cells were fixed and stained according to previously published protocols for intracellular stainings and TF-flow (44). In short, the (1) intracellular staining protocol uses the Fix/Perm kit from BD Biosciences according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Cytofix 554655; Perm. Buffer 558050) and the (2) TF staining protocol uses the Foxp3 fixation buffer (eBioscience, through Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Foxp3 permeabilization buffer (eBioscience). (1) For the intracellular staining, cells were extracellularly stained for 20 min at 4°C with saturating concentrations of CD19 APC-R700 (564977; BD Biosciences). Labeled cells were fixed and permeabilized using the Fix/Perm kit from BD Biosciences. Cell pellets were divided into two separate stainings (indicated as panels 2 and 3). Next, cells were stained intracellularly in PBA with saturating concentrations of the following fluorescently labeled mAbs: CD3 BV421 (562426; BD Biosciences), pERK 1/2 (T202/Y204) (560115; BD Phosflow), NF-κB p65 PE (653003; BioLegend), NF-κB phospho-p65 (S529) PE-Cy7 (560335; BD Biosciences), IκBα Alexa 647 (8993S; Cell Signaling), or NF-κB acetyl-p65 (k310) (ab19870; Abcam), and in combination with a secondary Ab in APC (709-136-149; Jackson ImmunoResearch) after incubation and washing. (2) For the TF staining (indicated as panel 4), cells were stained with 1:1,000 LIVE/DEAD Fixable Near-IR Dead Cell Stain Kit and CD19 BV510 (562947; BD Biosciences), SLAMF7 PE-Cy7 (331815; BioLegend), and CD38 V450 (646851; BD Biosciences) with or without CD27 BUV395 (563815; BD Biosciences) antibodies. Cells were incubated for 15 min in the fridge. Next, cells were washed and fixed using Foxp3 permeabilization buffer (eBioscience) on ice. After a washing step with this buffer, samples were stained with 25 μl of staining mix containing anti-PAX5 PE (649708; BioLegend), IRF4-PerCP-Cy5-5 (646415; BioLegend), anti-BLIMP1 AF647 (IC36081R-025; R&D Systems), pSTAT3 (612569; BD Biosciences), and tSTAT3 (564133; BD Biosciences) diluted in Foxp3 permeabilization buffer and incubated for 30 min in the fridge. The samples were washed and resuspended in a volume and measured on a BD FACSymphony A3 or A5 machine. The flow cytometer was calibrated by compensating for all conjugates using UltraComp eBeads Compensation Beads (Invitrogen). The data were analyzed using FlowJo software, v10.6.2 (Treestar).

FACS

In separate experiments, CFSE-labeled PBMCs were resuspended in a culture medium and incubated with saturating concentrations of dye-conjugated mAbs for 30 min at 4°C. Naïve (CD20+CD19+IgD+CD27−), non-switched (CD20+CD19+IgD+CD27+), and memory (CD20+CD19+IgD−CD27+) B-cell populations and non–B-cell populations (CD19−) were isolated by FACS with a FACSAria II (BD Biosciences) dependent on the experiment. In addition, from the non–B-cell fraction, total CD3+ T cells (CD3+CD19−) were isolated for specific experiments. The following mAbs were used for isolation: CD3 PE (347247; BD Biosciences), CD19 APC-R700 (564977; BD Biosciences), CD27 APC (337169; BD Biosciences), and IgD PE (555779; BD Biosciences). Different combinations, at a fixed number of cells (25,000 B cells with 125,000 non-B cells) or 100,000 T cells, were then cultured in 96-well U-bottom plates for 6 d. During culture, the cells were stimulated with CpG or αCD40 + IL-21 with or without concentrations of daratumumab as described above. T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 (αCD3) (clone 1xE; Sanquin) and 10 μg/ml anti-CD28 (αCD28) (clone 15E8; Sanquin) with or without daratumumab. After 6 d, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry as described above. Supernatants were collected for further analysis.

IgG, IgA, and IgM ELISA

The secretion of IgG, IgA, and IgM by cultured B cells was assessed with an in-house ELISA protocol using polyclonal rabbit anti-human IgG, IgA, and IgM, and a serum protein calibrator (all from Dako) as described previously (29).

Statistics

Differences between the relative expression of markers and the secretion of immunoglobulins were calculated with a one-way or two-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test where indicated. A P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Appendix: T2B Consortium Members.

| PhD/Postdocs | Clinical partners |

|---|---|

| Name, Institute | Name, Institute |

| Mrs. Annabel Ruiter, LUMC | Dr. Filip Eftimov, AMC |

| Mrs. Linda van der Weele, AMC | Dr. Casper Franssen, UMCG |

| Mrs. Karoline Kielbassa, AMC | Prof. Dr. Jaap Groothoff, AMC |

| Mrs. Mariateresa Coppola, VUMC | Prof. Dr. Bart Jacobs Erasmus, MC |

| Mrs. Dorit Verhoeven, AMC | Dr. Barbara Horvath, UMCG |

| Mrs. Jyaysi Desai, LUMC | Prof. Dr. Arnon Kater, AMC |

| Mrs. Mirjam van der Burg, LUMC | Dr. Joep Killestein, VUMC |

| Mrs. Esther Vletter, LUMC | Prof. Dr. Taco Kuijpers, AMC |

| Mrs. Maaike Braham, RIVM | Dr. Karina de Leeuw, UMCG |

| Mr. Matthias Busch, MUMC | Dr. L Oosten, LUMC |

| Mr. Carlo Bonasia, UMCG | Dr. Pieter van Paassen, UMC Maastricht |

| Mrs. Elisabeth Raveling, UMCG | Dr. Bram Rutgers, UMCG |

| Mrs. Ruth Huizinga, ErasmusMC | Dr. Uli Scherer, LUMC |

| Mr. Niels Verstegen, Sanquin | Dr. Maarten Titulaer, ErasmusMC |

| Mr. Casper Marsman, Sanquin | Prof. Dr. Jan Verschuuren, LUMC |

| Mrs. Sabrina Pollastro, Sanquin | Dr. Niek de Vries, AMC |

| Mr. Koos van Dam, AMC | Dr. Diane van der Woude, LUMC |

| Mr. Laurent Paardekooper, LUMC | Dr. Josephine Vos, AMC |

| Mrs. Renée Ysermans, MUMC | Prof. Dr. Hendrik Veelken, LUMC |

| Mrs. Odilia Corneth, ErasmusMC | |

| Mrs. Annemarie Buisman, RIVM | |

| Mr. Rob van Binnendijk, RIVM | |

| Mrs. Pauline van Schouwenburg, LUMC | |

| Mr. Marvyn Koning, LUMC | |

| Mr. Luuk Wieske, AMC | |

| Fundamental partners (group leaders/division heads) | |

| Dr. Lisa van Baarsen, AMC | |

| Prof. Dr. Nico Bos, UMCG | |

| Dr. Anja ten Brinke, Sanquin | |

| Dr. Eric Eldering, AMC | |

| Dr. Cecile van Els, RIVM | |

| Prof. Dr. Marieke van Ham, Sanquin | |

| Prof. Dr. Peter Heeringa, UMCG | |

| Prof. Dr. Rudi Hendriks, ErasmusMC | |

| Dr. Maartje Huijbers, LUMC | |

| Dr. Ruth Huizinga, ErasmusMC | |

| Prof. Dr. Reina Mebius, VUMC | |

| Dr. Theo Rispens, Sanquin | |

| Prof. Dr. Rene Toes, LUMC | |

| Dr. Jelle de Wit, RIVM | |

| Dr. Jan Damoiseaux, MUMC | |

| Dr. Wayel Abdulahad, UMCG | |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the healthy donors that donated blood. We thank the Amsterdam UMC Pharmacy for the provision of left-over Darzalex and Xolair. We acknowledge the support of patient partners, private partners, and active colleagues of the T2B consortium (see website: www.target-to-b.nl). We thank the Sanquin Central Facility and the Laboratory Medical Immunology Amsterdam UMC for the maintenance and calibration of the FACS machines. This collaboration project is financed by the PPP Allowance made available by Top Sector Life Sciences and Health to Samenwerkende Gezondheidsfondsen (SGF) under project number LSHM18055-SGF to stimulate public–private partnerships and co-financing by health foundations that are part of the SGF.

Author Contributions

D Verhoeven: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, methodology, and writing—original draft, review, and editing.

L Grinwis: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, and writing—original draft.

C Marsman: formal analysis, investigation, methodology, and writing—review and editing.

MH Jansen: data curation, formal analysis, and investigation.

EMM Van Leeuwen: conceptualization, supervision, and writing—original draft, review, and editing.

TW Kuijpers: conceptualization, supervision, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, and writing—original draft, review, and editing.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Nutt SL, Hodgkin PD, Tarlinton DM, Corcoran LM (2015) The generation of antibody-secreting plasma cells. Nat Rev Immunol 15: 160–171. 10.1038/nri3795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allman D, Wilmore JR, Gaudette BT (2019) The continuing story of T-cell independent antibodies. Immunol Rev 288: 128–135. 10.1111/imr.12754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ettinger R, Sims GP, Fairhurst AM, Robbins R, da Silva YS, Spolski R, Leonard WJ, Lipsky PE (2005) IL-21 induces differentiation of human naive and memory B cells into antibody-secreting plasma cells. J Immunol 175: 7867–7879. 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.7867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tellier J, Nutt SL (2017) Standing out from the crowd: How to identify plasma cells. Eur J Immunol 47: 1276–1279. 10.1002/eji.201747168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cobaleda C, Schebesta A, Delogu A, Busslinger M (2007) Pax5: The guardian of B cell identity and function. Nat Immunol 8: 463–470. 10.1038/ni1454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisenberg R, Albert D (2006) B-cell targeted therapies in rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol 2: 20–27. 10.1038/ncprheum0042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rajkumar SV, Kumar S (2020) Multiple myeloma current treatment algorithms. Blood Cancer J 10: 94. 10.1038/s41408-020-00359-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dimopoulos MA, San-Miguel J, Belch A, White D, Benboubker L, Cook G, Leiba M, Morton J, Ho PJ, Kim K, et al. (2018) Daratumumab plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone versus lenalidomide and dexamethasone in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: Updated analysis of POLLUX. Haematologica 103: 2088–2096. 10.3324/haematol.2018.194282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moreau P, Attal M, Hulin C, Arnulf B, Belhadj K, Benboubker L, Béné MC, Broijl A, Caillon H, Caillot D, et al. (2019) Bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone with or without daratumumab before and after autologous stem-cell transplantation for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (CASSIOPEIA): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet 394: 29–38. 10.1016/s0140-6736(19)31240-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petrucci MT, Vozella F (2019) The anti-CD38 antibody therapy in multiple myeloma. Cells 8: 1629. 10.3390/cells8121629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pimpinelli F, Marchesi F, Piaggio G, Giannarelli D, Papa E, Falcucci P, Pontone M, Di Martino S, Laquintana V, La Malfa A, et al. (2021) Fifth-week immunogenicity and safety of anti-SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 vaccine in patients with multiple myeloma and myeloproliferative malignancies on active treatment: Preliminary data from a single institution. J Hematol Oncol 14: 81. 10.1186/s13045-021-01090-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Oekelen O, Gleason CR, Agte S, Srivastava K, Beach KF, Aleman A, Kappes K, Mouhieddine TH, Wang B, Chari A, et al. (2021) Highly variable SARS-CoV-2 spike antibody responses to two doses of COVID-19 RNA vaccination in patients with multiple myeloma. Cancer Cell 39: 1028–1030. 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henriquez S, Zerbit J, Bruel T, Ouedrani A, Planas D, Deschamps P, Staropoli I, Hadjadj J, Varet B, Ermak N, et al. (2022) Anti-CD38 therapy impairs SARS-CoV-2 vaccine response against alpha and delta variants in patients with multiple myeloma. Blood 139: 942–946. 10.1182/blood.2021013714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnsrud AJ, Johnsrud JJ, Susanibar SA, Kamimoto JJ, Kothari A, Burgess M, Van Rhee F, Rico JC (2019) Infectious and immunological sequelae of daratumumab in multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol 185: 187–189. 10.1111/bjh.15433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frerichs KA, Verkleij CP, Bosman PW, Zweegman S, Otten H, van de Donk NW (2019) CD38-targeted therapy with daratumumab reduces autoantibody levels in multiple myeloma patients. J Transl Autoimmun 2: 100022. 10.1016/j.jtauto.2019.100022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glaría E, Valledor AF (2020) Roles of CD38 in the immune response to infection. Cells 9: 228. 10.3390/cells9010228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szlasa W, Czarny J, Sauer N, Rakoczy K, Szymańska N, Stecko J, Kołodziej M, Kaźmierczak M, Barg E (2022) Targeting CD38 in neoplasms and non-cancer diseases. Cancers (Basel) 14: 4169. 10.3390/cancers14174169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao YJ, Lam CMC, Lee HC (2012) The membrane-bound enzyme CD38 exists in two opposing orientations. Sci Signal 5: ra67. 10.1126/scisignal.2002700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Franco L, Guida L, Bruzzone S, Zocchi E, Usai C, De Flora A (1998) The transmembrane glycoprotein CD38 is a catalytically active transporter responsible for generation and influx of the second messenger cyclic ADP-ribose across membranes. Faseb j 12: 1507–1520. 10.1096/fasebj.12.14.1507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee HC, Deng QW, Zhao YJ (2022) The calcium signaling enzyme CD38 - a paradigm for membrane topology defining distinct protein functions. Cell Calcium 101: 102514. 10.1016/j.ceca.2021.102514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aarhus R, Graeff RM, Dickey DM, Walseth TF, Hon CL (1995) ADP-ribosyl cyclase and CD38 catalyze the synthesis of a calcium-mobilizing metabolite from NADP+. J Biol Chem 270: 30327–30333. 10.1074/jbc.270.51.30327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Camacho-Pereira J, Tarragó MG, Chini CC, Nin V, Escande C, Warner GM, Puranik AS, Schoon RA, Reid JM, Galina A, et al. (2016) CD38 dictates age-related NAD decline and mitochondrial dysfunction through an SIRT3-dependent mechanism. Cell Metab 23: 1127–1139. 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chini CCS, Zeidler JD, Kashyap S, Warner G, Chini EN (2021) Evolving concepts in NAD(+) metabolism. Cell Metab 33: 1076–1087. 10.1016/j.cmet.2021.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qian Y, Chen C, Ma L, Wang Z, Wang LF, Zuo L, Yang Y, Huang X, Jiang M, Wang X, et al. (2018) CD38 deficiency promotes inflammatory response through activating Sirt1/NF-κB-Mediated inhibition of TLR2 expression in macrophages. Mediators Inflamm 2018: 8736949. 10.1155/2018/8736949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aksoy P, Escande C, White TA, Thompson M, Soares S, Benech JC, Chini EN (2006) Regulation of SIRT 1 mediated NAD dependent deacetylation: A novel role for the multifunctional enzyme CD38. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 349: 353–359. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.08.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deaglio S, Morra M, Mallone R, Ausiello CM, Prager E, Garbarino G, Dianzani U, Stockinger H, Malavasi F (1998) Human CD38 (ADP-ribosyl cyclase) is a counter-receptor of CD31, an Ig superfamily member. J Immunol 160: 395–402. 10.4049/jimmunol.160.1.395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lund FE, Yu N, Kim KM, Reth M, Howard MC (1996) Signaling through CD38 augments B cell antigen receptor (BCR) responses and is dependent on BCR expression. J Immunol 157: 1455–1467. 10.4049/jimmunol.157.4.1455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Camponeschi A, Kläsener K, Sundell T, Lundqvist C, Manna PT, Ayoubzadeh N, Sundqvist M, Thorarinsdottir K, Gatto M, Visentini M, et al. (2022) Human CD38 regulates B cell antigen receptor dynamic organization in normal and malignant B cells. J Exp Med 219: e20220201. 10.1084/jem.20220201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.aan de Kerk DJ, Jansen MH, ten Berge IJM, van Leeuwen EMM, Kuijpers TW (2013) Identification of B cell defects using age-defined reference ranges for in vivo and in vitro B cell differentiation. J Immunol 190: 5012–5019. 10.4049/jimmunol.1201807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tuijnenburg P, aan de Kerk DJ, Jansen MH, Morris B, Lieftink C, Beijersbergen RL, Leeuwen EM, Kuijpers TW (2020) High-throughput compound screen reveals mTOR inhibitors as potential therapeutics to reduce (auto)antibody production by human plasma cells. Eur J Immunol 50: 73–85. 10.1002/eji.201948241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clemens PL, Yan X, Lokhorst HM, Lonial S, Losic N, Khan I, Jansson R, Ahmadi T, Lantz K, Zhou H, et al. (2017) Pharmacokinetics of daratumumab following intravenous infusion in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma after prior proteasome inhibitor and immunomodulatory drug treatment. Clin Pharmacokinet 56: 915–924. 10.1007/s40262-016-0477-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perincheri S, Torres R, Tormey CA, Smith BR, Rinder HM, Siddon AJ (2016) Daratumumab interferes with flow cytometric evaluation of multiple myeloma. Blood 128: 5630. 10.1182/blood.v128.22.5630.5630 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oberle A, Brandt A, Alawi M, Langebrake C, Janjetovic S, Wolschke C, Schütze K, Bannas P, Kröger N, Koch-Nolte F, et al. (2017) Long-term CD38 saturation by daratumumab interferes with diagnostic myeloma cell detection. Haematologica 102: e368–e370. 10.3324/haematol.2017.169235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soh KT, Tario JD, Hahn T, Hillengass J, McCarthy PL, Wallace PK (2020) CD319 (SLAMF7) an alternative marker for detecting plasma cells in the presence of daratumumab or elotuzumab. Cytometry B Clin Cytom 100: 497–508. 10.1002/cyto.b.21961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vaisitti T, Aydin S, Rossi D, Cottino F, Bergui L, D’Arena G, Bonello L, Horenstein AL, Brennan P, Pepper C, et al. (2010) CD38 increases CXCL12-mediated signals and homing of chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Leukemia 24: 958–969. 10.1038/leu.2010.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Darce JR, Arendt BK, Wu X, Jelinek DF (2007) Regulated expression of BAFF-binding receptors during human B cell differentiation. J Immunol 179: 7276–7286. 10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martens AWJ, Rietveld JM, de Boer R, Peters FS, Ngo A, van Mil LW, de Heer K, Spaargaren M, Verkleij CP, van de Donk NW, et al. (2022) Redirecting T-cell activity with anti-BCMA/anti-CD3 bispecific antibodies in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and other B-cell lymphomas. Cancer Res Commun 2: 330–341. 10.1158/2767-9764.crc-22-0083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Weers M, Tai YT, van der Veer MS, Bakker JM, Vink T, Jacobs DCH, Oomen LA, Peipp M, Valerius T, Slootstra JW, et al. (2011) Daratumumab, a novel therapeutic human CD38 monoclonal antibody, induces killing of multiple myeloma and other hematological tumors. J Immunol 186: 1840–1848. 10.4049/jimmunol.1003032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sasaki Y, Iwai K (2016) Roles of the NF-κB pathway in B-lymphocyte biology. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 393: 177–209. 10.1007/82_2015_479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen L-F, Greene WC (2004) Shaping the nuclear action of NF-κB. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5: 392–401. 10.1038/nrm1368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen L-f, Mu Y, Greene WC (2002) Acetylation of RelA at discrete sites regulates distinct nuclear functions of NF-kappaB. EMBO J 21: 6539–6548. 10.1093/emboj/cdf660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perkins ND, Gilmore TD (2006) Good cop, bad cop: The different faces of NF-κB. Cell Death Differ 13: 759–772. 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mattioli I, Sebald A, Bucher C, Charles RP, Nakano H, Doi T, Kracht M, Schmitz ML (2004) Transient and selective NF-κB p65 serine 536 phosphorylation induced by T cell costimulation is mediated by IκB kinase β and controls the kinetics of p65 nuclear import. J Immunol 172: 6336–6344. 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marsman C, Jorritsma T, ten Brinke A, van Ham SM (2020) Flow cytometric methods for the detection of intracellular signaling proteins and transcription factors reveal heterogeneity in differentiating human B cell subsets. Cells 9: 2633. 10.3390/cells9122633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malavasi F, Deaglio S, Funaro A, Ferrero E, Horenstein AL, Ortolan E, Vaisitti T, Aydin S (2008) Evolution and function of the ADP ribosyl cyclase/CD38 gene family in physiology and pathology. Physiol Rev 88: 841–886. 10.1152/physrev.00035.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krejcik J, Casneuf T, Nijhof IS, Verbist B, Bald J, Plesner T, Syed K, Liu K, van de Donk NWCJ, Weiss BM, et al. (2016) Daratumumab depletes CD38+ immune regulatory cells, promotes T-cell expansion, and skews T-cell repertoire in multiple myeloma. Blood 128: 384–394. 10.1182/blood-2015-12-687749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ostendorf L, Burns M, Wagner DL, Enghard P, Amann K, Mei H, Eckardt KU, Seelow E, Schreiber A (2023) Daratumumab for the treatment of refractory ANCA-associated vasculitis. RMD Open 9: e002742. 10.1136/rmdopen-2022-002742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ibrahim S, El-Osh SS, El-Halim AFA, El-Rhman HAEA (2021) The importance of CD319 marker in diagnosis and prognosis of plasma cell myeloma patients. Ann Rom Soc Cell Biol 25: 15923–15932. 10.21608/EJHM.2021.184227 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu XS, Yan X, Puchalski T, Lonial S, Lokhorst H, Voorhees P, Plesner T, Liu K, Khan I, Jansson R, et al. (2017) Clinical implications of complex pharmacokinetics for daratumumab dose regimen in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Clin Pharmacol Ther 101: 721–724. 10.1002/cpt.577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Htut TW, Tun AM, Sultan A, Win MA, Swarup S, Phyu EM, Hlaing PP, Han MM, Myat YM, Hardwicke F, et al. (2019) Updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials to evaluate the incidence of infection and pneumonia in patients with multiple myeloma treated with daratumumab. Blood 134: 4771. 10.1182/blood-2019-123169 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arnall JR, Maples KT, Harvey RD, Moore DC (2021) Daratumumab for the treatment of multiple myeloma: A review of clinical applicability and operational considerations. Ann Pharmacother 56: 927–940. 10.1177/10600280211058754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Paul Y, Aguirre LE, Basher F, Miao F, Koru-Sengul T, Hoffman JE (2019) Hypogammaglobulinemia and its implications in patients treated with daratumumab: A single institution experience. Blood 134: 3131. 10.1182/blood-2019-127247 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vitkon R, Netanely D, Levi S, Ziv-Baran T, Ben-Yzak R, Katz BZ, Benyamini N, Trestman S, Mittelman M, Cohen Y, et al. (2021) Daratumumab in combination with proteasome inhibitors, rapidly decreases polyclonal immunoglobulins and increases infection risk among relapsed multiple myeloma patients: A single center retrospective study. Ther Adv Hematol 12: 204062072110352. 10.1177/20406207211035272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crickx E, Audia S, Robbins A, Boutboul D, Comont T, Cheminant M, Oksenhendler E, Godeau B, Michel M, Mahevas M (2021) Daratumumab, an original approach for treating multi-refractory autoimmune cytopenia. Haematologica 106: 3198–3201. 10.3324/haematol.2021.279232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nahi H, Chrobok M, Gran C, Lund J, Gruber A, Gahrton G, Ljungman P, Wagner AK, Alici E (2019) Infectious complications and NK cell depletion following daratumumab treatment of multiple myeloma. PLoS One 14: e0211927. 10.1371/journal.pone.0211927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bitoun S, Henry J, Vauloup-Fellous C, Dib N, Belkhir R, Mouna L, Joly C, Desjardins D, Bitu M, Le Grand R, et al. (2021) Response to COVID-19 mRNA vaccination in multiple myeloma is conserved but impaired compared to controls. J Hematol Oncol 14: 166. 10.1186/s13045-021-01183-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kar A, Mehrotra S, Chatterjee S (2020) CD38: T cell immuno-metabolic modulator. Cells 9: 1716. 10.3390/cells9071716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kennedy BE, Sadek M, Elnenaei MO, Reiman A, Gujar SA (2020) Targeting NAD+ synthesis to potentiate CD38-based immunotherapy of multiple myeloma. Trends Cancer 6: 9–12. 10.1016/j.trecan.2019.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hogan KA, Chini CCS, Chini EN (2019) The multi-faceted ecto-enzyme CD38: Roles in immunomodulation, cancer, aging, and metabolic diseases. Front Immunol 10: 1187. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chatterjee S, Daenthanasanmak A, Chakraborty P, Wyatt MW, Dhar P, Selvam SP, Fu J, Zhang J, Nguyen H, Kang I, et al. (2018) CD38-NAD+Axis regulates immunotherapeutic anti-tumor T cell response. Cell Metab 27: 85–100.e8. 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Malavasi F, Faini AC, Morandi F, Castella B, Incarnato D, Oliviero S, Horenstein AL, Massaia M, Donk NWCJ, Richardson PG (2021) Molecular dynamics of targeting CD38 in multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol 193: 581–591. 10.1111/bjh.17329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martin TG, Corzo K, Chiron M, van de Velde H, Abbadessa G, Campana F, Solanki M, Meng R, Lee H, Wiederschain D, et al. (2019) Therapeutic opportunities with pharmacological inhibition of CD38 with isatuximab. Cells 8: 1522. 10.3390/cells8121522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Morandi F, Morandi B, Horenstein AL, Chillemi A, Quarona V, Zaccarello G, Carrega P, Ferlazzo G, Mingari MC, Moretta L, et al. (2015) A non-canonical adenosinergic pathway led by CD38 in human melanoma cells induces suppression of T cell proliferation. Oncotarget 6: 25602–25618. 10.18632/oncotarget.4693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hesse J, Siekierka-Harreis M, Steckel B, Alter C, Schallehn M, Honke N, Schnieringer ML, Wippich M, Braband R, Schneider M, et al. (2021) Profound inhibition of CD73-dependent formation of anti-inflammatory adenosine in B cells of SLE patients. eBioMedicine 73: 103616. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fortuny L, Sebastián C (2021) Sirtuins as metabolic regulators of immune cells phenotype and function. Genes (Basel) 12: 1698. 10.3390/genes12111698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ma Y, Chen H, He X, Nie H, Hong Y, Sheng C, Wang Q, Xia W, Ying W (2012) NAD+ metabolism and NAD(+)-dependent enzymes: Promising therapeutic targets for neurological diseases. Curr Drug Targets 13: 222–229. 10.2174/138945012799201711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ambrose HE, Willimott S, Beswick RW, Dantzer F, de Murcia JM, Yelamos J, Wagner SD (2009) Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (Parp-1)-deficient mice demonstrate abnormal antibody responses. Immunology 127: 178–186. 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02921.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gan H, Shen T, Chupp DP, Taylor JR, Sanchez HN, Li X, Xu Z, Zan H, Casali P (2020) B cell Sirt1 deacetylates histone and non-histone proteins for epigenetic modulation of AID expression and the antibody response. Sci Adv 6: eaay2793. 10.1126/sciadv.aay2793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Frerichs KA, Bosman PW, van Velzen JF, Fraaij PL, Koopmans MP, Rimmelzwaan GF, Nijhof IS, Bloem AC, Mutis T, Zweegman S, et al. (2020) Effect of daratumumab on normal plasma cells, polyclonal immunoglobulin levels, and vaccination responses in extensively pre-treated multiple myeloma patients. Haematologica 105: e302–e306. 10.3324/haematol.2019.231860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ochoa S, Ding L, Kreuzburg S, Treat J, Holland SM, Zerbe CS (2020) Daratumumab (anti-CD38) for treatment of disseminated nontuberculous mycobacteria in a patient with anti–interferon-γ autoantibodies. Clin Infect Dis 72: 2206–2208. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pleguezuelo DE, Díaz-Simón R, Cabrera-Marante O, Lalueza A, Paz-Artal E, Lumbreras C, Serrano Hernández A (2021) Case report: Resetting the humoral immune response by targeting plasma cells with daratumumab in anti-phospholipid syndrome. Front Immunol 12: 667515. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.667515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Scheibe F, Ostendorf L, Reincke SM, Prüss H, von Brünneck AC, Köhnlein M, Alexander T, Meisel C, Meisel A (2020) Daratumumab treatment for therapy-refractory anti-CASPR2 encephalitis. J Neurol 267: 317–323. 10.1007/s00415-019-09585-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ratuszny D, Skripuletz T, Wegner F, Groß M, Falk C, Jacobs R, Ruschulte H, Stangel M, Sühs KW (2020) Case report: Daratumumab in a patient with severe refractory anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis. Front Neurol 11: 602102. 10.3389/fneur.2020.602102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tomkins O, Berentsen S, Arulogun S, Sekhar M, D’Sa S (2020) Daratumumab for disabling cold agglutinin disease refractory to B-cell directed therapy. Am J Hematol 95: E293–E295. 10.1002/ajh.25932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zaninoni A, Giannotta JA, Gallì A, Artuso R, Bianchi P, Malcovati L, Barcellini W, Fattizzo B (2021) The immunomodulatory effect and clinical efficacy of daratumumab in a patient with cold agglutinin disease. Front Immunol 12: 649441. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.649441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kastritis E, Palladini G, Minnema MC, Wechalekar AD, Jaccard A, Lee HC, Sanchorawala V, Gibbs S, Mollee P, Venner CP, et al. (2021) Daratumumab-based treatment for immunoglobulin light-chain amyloidosis. N Engl J Med 385: 46–58. 10.1056/nejmoa2028631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tiew HW, Sampath VS, Gallardo CA, Christopher D, Chan SSW, Wong SW, Tso ACY, Lee LK, Fan BE (2022) Single-agent daratumumab for refractory POEMS syndrome. Am J Hematol 97: E189–E191. 10.1002/ajh.26517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schuetz C, Hoenig M, Moshous D, Weinstock C, Castelle M, Bendavid M, Shimano K, Tolbert V, Schulz AS, Dvorak CC (2018) Daratumumab in life-threatening autoimmune hemolytic anemia following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood Adv 2: 2550–2553. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018020883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Migdady Y, Ediriwickrema A, Jackson RP, Kadi W, Gupta R, Socola F, Arai S, Martin BA (2020) Successful treatment of thrombocytopenia with daratumumab after allogeneic transplant: A case report and literature review. Blood Adv 4: 815–818. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019001215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chapuy CI, Kaufman RM, Alyea EP, Connors JM (2018) Daratumumab for delayed red-cell engraftment after allogeneic transplantation. New Engl J Med 379: 1846–1850. 10.1056/nejmoa1807438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zand L, Rajkumar SV, Leung N, Sethi S, El Ters M, Fervenza FC (2021) Safety and efficacy of daratumumab in patients with proliferative GN with monoclonal immunoglobulin deposits. J Am Soc Nephrol 32: 1163–1173. 10.1681/asn.2020101541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ostendorf L, Burns M, Durek P, Heinz GA, Heinrich F, Garantziotis P, Enghard P, Richter U, Biesen R, Schneider U, et al. (2020) Targeting CD38 with daratumumab in refractory systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med 383: 1149–1155. 10.1056/nejmoa2023325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.