Abstract

Studies have identified sex and/or gender differences in Alzheimer’s disease, but few have examined other dementias. We highlight sex and gender differences in other dementias, discuss sociocultural factors and provide a framework for future global studies.

Several studies from Europe and Asia have suggested that women have a higher incidence of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) than men, according to a recent perspective1. By contrast, studies conducted in North and South America have not typically reported sex or gender differences in the incidence of AD. These globally disparate results suggest relevant social, cultural, demographic and historical factors that vary by sex or gender and contribute to AD risk. Indeed, sex and gender differences in AD risk factors have been identified, and include depression, diet, physical activity, cardiometabolic factors and sleep disorders1. Sex-specific conditions also affect AD risk, including hypertensive disorders of pregnancy or early menopause and menopausal hormonal therapy for female individuals, and prostate cancer or androgen deprivation therapy for male individuals2. Notably, the prevalence of these risk factors varies across races and ethnicities, cultures, and global regions. Sociocultural aspects that lead to gender inequities (for example, access to education, employment or occupation characteristics, healthcare access and discrimination) also increase the risk of AD. There is a critical need to understand the intersection of sex-related factors, sociocultural gender roles and race and ethnicity for risk of AD globally, particularly in low- and middle-income countries.

Despite growing evidence of sex and gender differences in AD, considerably less is known for non-AD dementias, including Lewy body dementias (LBDs), frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia (VCID). In this Comment, we provide an overview of sex and gender differences in the incidence, risk factors and clinical presentations of non-AD dementias. We also discuss research guidelines for future studies of non-AD dementias that consider sex and gender differences in the context of geographical regions, sociocultural factors and the intersection with race and ethnicity.

Sex and gender differences in non-AD dementias

LBDs.

LBDs include dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease dementia. LBDs are progressive diseases that are characterized by fluctuating cognition, visual hallucinations, mood disorders and autonomic dysfunction caused by abnormal deposits of α-synuclein in the brain3. The prevalence of LBDs is higher for men than women, at a 4:1 ratio3. Hormonal mechanisms may account for some of this difference; animal studies suggest that estrogen protects dopaminergic neurons from susceptibility to α-synuclein aggregation4. Several environmental risk factors have been identified, including exposure to pesticides, water pollutants and lifestyle factors (for example, smoking, sedentarism and head trauma). However, little is known about how sex and gender affect exposure to environmental risk factors and subsequent LBD risk – particularly in low- and middle-income countries, where (for example) there are higher levels of ambient and indoor air pollution. Future studies should assess the intersection of sex and gender with social, cultural and environmental factors for the risk of LBDs, which varies globally.

FTD.

FTD encompasses clinical syndromes that are characterized by changes in behavior, personality or language. Clinical phenotypes include behavioral-variant FTD, semantic-variant primary progressive aphasia (PPA), non-fluent variant PPA and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) associated with FTD (ALS–FTD). Behavioral-variant FTD is more common in male individuals than female individuals, but sex differences in PPA subtypes are inconclusive. Studies of sex or gender differences in clinical presentations have yielded mixed findings. Some studies (for example, ref. 5) have reported worse cognitive performance in female individuals with behavioral-variant FTD or PPA, whereas another study has suggested women demonstrate greater cognitive resilience to FTD pathology6. Sex-specific genetic risk factors may exist. A meta-analysis found a higher female prevalence of C9orf72 mutations, the most common known genetic cause of both ALS and FTD7. Sex differences in the prevalence of sporadic versus genetic behavioral-variant FTD have also been reported8. It is vital for future research to examine the influence of gender on the risk and presentation of FTD, especially from a global perspective, because social acceptance of the behavioral symptoms due to FTD varies.

VCID.

The term VCID broadly refers to cognitive dysfunction caused by cerebrovascular disease, including stroke, subclinical vascular brain injury and silent brain infarction. The clinical presentation is heterogeneous and depends on the etiology and location of the injury. Although some VCID studies have reported a higher prevalence in men, others have not reported a sex difference. Discrepancies are probably due to cohort-specific characteristics9.

Sex and gender differences in cardiovascular risk factors and response to treatments exist, but the effect of these differences on incident VCID are not well understood. Although the prevalence of mid-life cardiovascular risk factors is higher in men than women, their effects on mid-life cognitive decline may be greater for women10. In addition, female-specific cardiovascular risk factors that affect cognition (for example, pregnancy-related disorders and early menopause) should be considered. Knowledge of sex or gender differences in the prevalence and risk of VCID in low- and middle-income countries is scarce. It is important to investigate cultural and social factors that contribute to differences in VCID risk worldwide, including access to treatments and psychosocial stress.

Proposed research framework

Current operationalization of sex and gender measurements in dementia research. Sex and gender are complex phenomena; their consideration in dementia research has been both inconsistent and challenging. Sex (biological, physiological and genetic differences between male and female individuals) and gender (a social construct that reflects environmental, psychosocial and cultural influences) are still often used interchangeably1. As a result, independent or synergistic determinants of sex or gender on dementia risk are not well understood. For example, the intersectionality of pathophysiological mechanisms with historical trajectories of socioeconomic determinants of AD (for example, educational attainment, occupational complexity or gender-associated roles such as caregiving) is unknown. Notably, race and ethnicity interact with sex and gender, but this intersection is not commonly considered in dementia research. Further, most studies adopt a binary approach to the measurement of sex or gender without considering the existence of nonbinary populations. Lastly, many studies still merely ‘adjust’ for sex or gender rather than assessing differences using interactions.

Framework for analysis in dementia epidemiology and related studies.

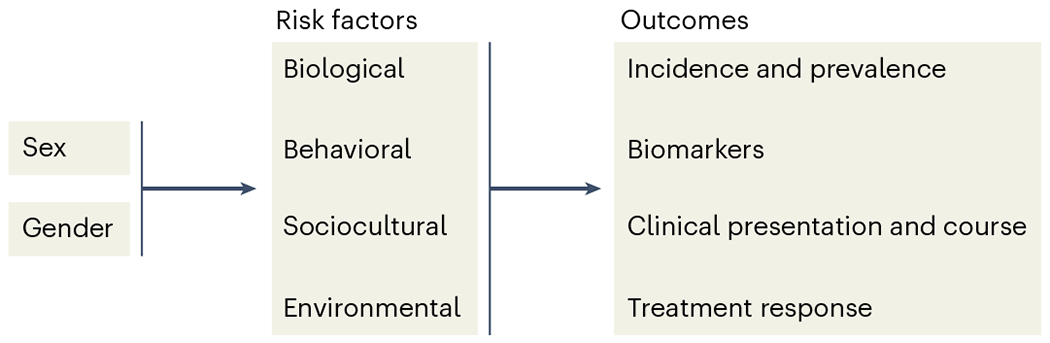

Although studies are beginning to examine sex and gender differences in risk factors for AD dementia1, and the efficacy of risk-reduction measures (Fig. 1), this work has rarely extended to other types of dementia. Future research must consider the limitations and challenges of the current operationalization of sex and gender measurements in dementia research.

Fig. 1 |. Proposed framework to investigate sex and gender differences in AD and non-AD dementias globally.

This framework will aid in the development of targeted interventions and treatments for AD and non-AD dementias.

Several factors may influence the accuracy of results for studies that examine sex and gender differences in AD and other dementias11. One issue is the misclassification of dementia subtypes, which occurs at both younger and older ages – particularly in studies with only clinical diagnoses and without in vivo biomarkers or brain autopsy. It has been estimated that over 95% of individuals with probable AD have mixed pathologies, and types of copathology may vary by sex and/or gender. For example, a neuropathological study of community-dwelling older adults reported women were significantly more likely to have combined AD and cardiovascular pathology, whereas men were more likely to have ‘pure’ LBDs12. Another study showed that men were more likely to have hippocampal sparing neurofibrillary tangle pathology, whereas women were more likely to have limbic predominant; the atypical pathological presentation in men – and corresponding atypical clinical presentation – led to an underdiagnosis of clinical AD for men13. A second issue is the identification of sex and gender differences in cognitive reserve and resilience to AD pathology14; additional research is needed to elucidate the sex-related factors (for example, sex chromosomes or hormones) and gendered experiences (for example, education, occupation or gender roles) that contribute to reserve and resilience, especially in non-AD dementias.

Another challenge relates to inferential errors from epidemiological studies (for example, inadequate consideration of survival or selection bias by sex or gender) and death as a competing risk. Women live longer than men and, therefore, have a longer timeframe to accrue a dementia diagnosis. Thus, the lifetime risk of AD for women is greater than for men – a finding that is widely reported in the literature, including across diverse populations (reviewed in ref. 2) – but the age-specific prevalence may not be. It is important to explicitly account for systematic bias and error when describing sex and gender differences in dementia prevalence and risk factors.

Additional analytic methods should also be considered. First, to overcome construct-validity issues caused by the dichotomous classification of sex or gender, instruments that feature questions relating to ‘sex assigned at birth’ and ‘current gender one identifies with’ may be more accurate. Next, rather than adjusting for sex, analytical strategies should examine effect modification that includes interactions of the investigated variables with sex, as well as mediation analysis that adopts a causal framework to examine gender-related mechanisms of sex differences. Finally, for a true comprehension of sex and gender differences across dementias, further research that includes wider geographical and culturally representative sampling across global populations and alongside multinational comparisons of sociocultural influences is essential, as recently shown15.

Summary and future directions

Dementia represents a global challenge – particularly in low- and middle-income countries, where the number of older people is predicted to rise substantially owing to increases in life expectancy. Growing evidence suggests that there are sex and gender differences in AD risk, but research examining differences in non-AD dementias has been limited. In this Comment, we reviewed current evidence for sex and gender differences in LBDs, FTD and VCID; highlighted the need to examine geographical and sociocultural factors; and provided a framework of important considerations when examining sex and gender differences for dementia. Identifying global drivers of sex and gender differences in AD and other dementias is a crucial step for developing interventions that are unique to each geographical and sociocultural area, to reduce dementia disparities and inequities.

Acknowledgements

C.V.-C. receives funding from the National Institute on Aging (NIA) K99AG073452. M.M.M. receives funding from the National Institute on Aging (RF1 AG055151, U54 AG044170, RF1 AG077386; RF1 AG079397). C.U.-M. is funded by Janssen R&D, Gates Ventures, Takeda and Merck, and received project grants from the RoseTrees Foundation Trust, Alzheimer Research UK and the British Society for Neuroendocrinology.

Footnotes

Competing interests

M.M.M. has served on scientific advisory boards and/or has consulted for Biogen, LabCorp, Lilly, Merck, PeerView Institute, Siemens Healthineers, and Sunbird Bio unrelated to the current manuscript. The other authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Mielke MM et al. Alzheimers Dement. 18, 2707–2724 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Udeh-Momoh C & Watermeyer T. Ageing Res. Rev 71, 101459 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kane JPM et al. Alzheimers Res. Ther 10, 19 (2018).29448953 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jurado-Coronel JC et al. Front. Neuroendocrinol 50, 18–30 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pengo M. et al. Neurol. Sci 43, 5281–5287 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Illán-Gala I. et al. Alzheimers Dement. 17, 1329–1341 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curtis AF et al. Neurology 89, 1633–1642 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Boer SCM et al. J. Alzheimers Dis 84, 1153–1161 (2021).34633319 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gannon O, Robison L, Custozzo A & Zuloaga K Neurochem. Internatl 127, 38–55 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huo N. et al. Neurology 98, e623–e632 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mayeda ER Am. J. Epidemiol 188, 1224–1227 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barnes LL, Lamar M & Schneider JA Brain Res. 1719, 11–16 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liesinger AM et al. Acta Neuropathol. 136, 873–885 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Subramaniapillai S. et al. Front. Neuroendocrinol 60, 100879 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huque H. et al. J. Alzheimers Dis 10.3233/JAD-220724 (2022). [DOI] [Google Scholar]