Abstract

Background

Immunotherapy is the first-line treatment in patients with advanced microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) or deficient mismatch repair (dMMR) colorectal cancer (CRC). Although immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) for locally advanced rectal cancer (LARC) are not yet a standard, the results are very encouraging and raise the question of whether patients with clinical complete response (cCR) could receive nonoperative management (NOM). However, different patterns of response have challenged management strategies.

Case Description

A 34-year-old woman diagnosed with dMMR LARC started treatment with capecitabine 2,000 mg/m2 on day 1 to 14 and oxaliplatin 130 mg/m2 on day 1 and every 21 days. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), performed three cycles later, showed local progression of the primary rectal lesion, which at that time had new peritoneal reflex involvement. A new hepatic lesion in segment V was observed. Due to disease progression, she was administered pembrolizumab 200 mg every 21 days. After three cycles, a discordant radiological response was observed on a new MRI scan that showed a complete response of the liver lesion and magnetic resonance tumor regression grade (mrTRG) 1 in the rectum. However, new involvement of the mesentery and enlargement of the regional lymph nodes (LNs) were also evident. A new colonoscopic biopsy was performed, showing no cancerous cells. She underwent surgery on the rectum and liver lesion. Pathology showed a complete response of the rectal wall and liver lesion, but 1 of 22 LNs was positive for adenocarcinoma (ypT0 N1 M0). The patient continued on pembrolizumab, and 14 months after surgery, she had not relapsed.

Conclusions

Neoadjuvant immunotherapy for rectal cancer requires new recommendations for the assessment of clinical response. Pseudoprogression should be ruled out as an atypical response before deciding on surgical treatment. We propose an algorithm to address pseudoprogression in this setting.

Keywords: Rectal cancer, case report, pseudoprogression, pembrolizumab, neoadjuvant

Highlight box.

Key findings

• Atypical response with neoadjuvant immunotherapy and lymph node remnant in rectal cancer.

What is known and what is new?

• ICIs for MSI-H/dMMR CRC are rapidly gaining ground as a neoadjuvant treatment because of high complete response rates that allow patients to avoid surgery.

• This case report and review highlight the importance of tailoring response evaluation criteria to the use of ICIs and understanding more about atypical responses such as pseudoprogression, and we propose an algorithm for treatment decisions for LARC and oligometastatic disease.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Improving current guidelines for tumor evaluation in this setting represents a new challenge. Careful evaluation by a multidisciplinary tumor board is crucial, and atypical responses should be taken into account for treatment personalization.

Introduction

Microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) or deficient mismatch repair (dMMR) is detected in approximately 10% to 15% of all sporadic colorectal cancers (CRCs) (1). Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have been established as a treatment option for patients with advanced MSI-H/dMMR CRC based on the KEYNOTE-177 Phase III randomized controlled trial. This pivotal study showed a statistically significant improvement in progression-free survival using pembrolizumab versus traditional chemotherapy (ChT) for first-line therapy in this particular patient subgroup (2).

Overall tumor response is a major efficacy outcome for most cancer types. In locally advanced rectal cancer (LARC), nonoperative management (NOM) strategies can be considered under certain conditions when a clinical complete response (cCR) is achieved. Current standard treatments include neoadjuvant radiotherapy and ChT. However, ICIs may add an intriguing benefit in patients with early and advanced MSI-H/dMMR CRC given the promising tumor response rates achieved in recent clinical trials (3). Currently, guidelines have not yet provided a recommendation regarding the use of immunotherapy for LARC. Further evidence is needed to understand the best sequence to incorporate this specific strategy in our current therapeutic algorithm.

In this context, we present a case report of a patient with dMMR LARC who developed one liver lesion. She was treated with pembrolizumab as neoadjuvant treatment with a discordant radiological response that after surgery showed a complete response in the rectal wall and only one positive lymph node (LN). To our knowledge, this is the first report of an atypical response and potential pseudoprogression in rectal cancer using this novel strategy. We present this case in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-22-1140/rc).

Case presentation

A 34-year-old Caucasian woman with suspected Lynch syndrome due to a familial history of a mother with a diagnosis of dMMR endometrial cancer presented with rectal bleeding. A diagnostic workup revealed a rectal lesion located 10 cm from the anal verge. The biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma. Further workup confirmed the presence of a Kirsten rat Sarcoma virus (KRAS G12D) mutation, and immunohistochemistry analysis showed an absence of Muts homolog (MSH)2 and MSH6 proteins. The patient underwent a germinal multigene panel analysis of 20 genes, which revealed the presence of a pathogenic variant of MSH6 (c.3720dup; p. Cys1241Metfs*34), confirming the Lynch syndrome diagnosis.

The rectal tumor was staged as cT3b N2b M0. The lesion was in contact with the circumferential margin, and no extramural vascular invasion (EMVI) was evident. A positron emission tomography (PET) scan showed increased uptake in the rectum and mesorectal and mesenteric LNs.

The patient started treatment with capecitabine 2,000 mg/m2 on days 1 to 14 and oxaliplatin 130 mg/m2 on day 1 and every 21 days. A new magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan performed three cycles later showed local progression of the rectal primary lesion, which at the time presented new peritoneal reflection involvement. Additionally, a new 7 mm liver lesion was noticed in segment V.

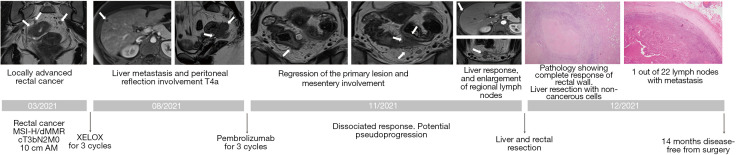

Due to progressive disease, the patient started pembrolizumab 200 mg every 21 days. After three cycles, a discordant radiological response was observed on a new MRI scan that showed a cCR of the liver lesion and magnetic resonance tumor regression grade (mrTRG) 1 in the rectum. However, new mesentery involvement and regional LN enlargement were also evident. A new colonoscopic biopsy was performed, and no cancerous cells were found. Given the discordant response, the Multidisciplinary Gastrointestinal Tumor Board of our institution recommended a surgical approach. The patient underwent an open rectosigmoid resection with total mesorectal excision and excision of the segment V liver lesion. The pathological analysis showed a complete response of the rectal wall and liver lesions, but 1 out of 22 LNs was positive for adenocarcinoma (ypT0 N1 M0). The patient continued with pembrolizumab, and after one month of treatment, she developed grade 2 hypothyroidism requiring hormone replacement. The patient is still under follow-up at our institution with good clinical conditions and without evidence of relapse from 14 months after surgery. Treatment is planned until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or completion of two years, based on the KEYNOTE-177 trial design (2). A summary of the case report is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Case report timeline. Cell images were obtained using hematoxylin-eosin as the staining method and ×10 magnification. MSI-H/dMMR, microsatellite instability-high/deficient mismatch repair; AM, anal margin; XELOX, capecitabine 2,000 mg/m2 days 1 to 14 and oxaliplatin 130 mg/m2 day 1 every 21 days.

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Discussion

Total neoadjuvant treatment based on chemoradiotherapy has the benefit of higher pathological complete response (pCR) rates in patients with LARC and potentially spares them from morbid resections and potential impairment of their quality of life (4). New approaches incorporate neoadjuvant immunotherapy for MSI-H/dMMR LARCs, and evidence for this promising strategy is beginning to emerge from the preliminary results of ongoing trials (5,6). Therefore, there are many doubts about the assessment of response to treatment and the future management of these patients. We are concerned by the atypical responses with immunotherapy, such as those we observed in our case. These are not considered in the criteria that we commonly use in imaging, such as Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST 1.1) or mrTRG (7-9).

To evaluate further evidence of this atypical response, we performed a literature review in the PubMed and Scopus databases, including articles describing case reports of patients who received neoadjuvant immunotherapy for MSI-H/dMMR LARCs from January 1, 2006, to January 1, 2022. The search strategy is detailed in the Appendix 1. Since 2006, six case reports have been reported, including 21 patients with MSI-H/dMMR LARC treated with immunotherapy in the neoadjuvant setting. Among the 21 patients included in the case reports, the therapies used included nivolumab (n=3), pembrolizumab (n=2), and ICIs combination [n=4, anti-programmed death-1 (PD-1) + anti-cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen (CTLA-4)]. Additionally, ChT and immunotherapy concurrently were administered in two cases. Of note, two of the patients had previously received ChT, and one underwent chemoradiotherapy. Overall, 17 patients (81%) presented cCR, and pCR was observed in 7 patients (33.3%) among those who underwent surgery. Of the reported cCR data, 4 patients were administered a combination of ICIs, and 12 patients received anti-PD-1 therapy. Interestingly, 14 patients out of 17 (82.4%) in whom cCR was obtained underwent a watch-and-wait strategy. Safety results were consistent with already reported experiences with immunotherapy. It is summarized in Table 1 (10-15). Importantly, none of these cases reported a response of the rectal wall and remaining LN, as in our case. On the other hand, Cercek and collaborators reported a phase II study with a higher quality of evidence for this specific population since they described the results of a prospective cohort of twelve patients with MSI-H/dMMR stage II–III rectal cancer who underwent neoadjuvant treatment with dostarlimab (anti-PD-1) for a total of 6 months. Notably, cCR was achieved in all patients, and NOM was proposed for all the participants. No recurrences were observed at a median follow-up of 12 months (6). Of interest, no cases with pseudoprogression were found. Table S1 summarizes the phase II studies conducted in a scoping search of PubMed using the terms “trials”, “rectal cancer”, “neoadjuvant”, and “immunotherapy” (6,16-18).

Table 1. Neoadjuvant therapy using immune checkpoint inhibitors for MSI-H/dMMR rectal cancer: case reports.

| Reference | n | Stage | MMR status | Previous treatment | Immunotherapy | Response | Strategy | Median follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhang J et al. (10), 2019 | 2 | III | Loss of MSH2 and MSH6 (n=2) | No (n=1); FOLFOXIRI (n=1) | Nivolumab (n=2) | cCR (n=1); cCR and pCR (n=1) |

Watch and Wait (n=1); TME (n=1) |

12 |

| Demisse R et al. (11), 2020 | 3 | II–III | Loss of MSH2 and MSH6 (n=1); loss PMS2 (n=2) |

No (n=2); FOLFOX followed by CRT with capecitabine (n=1) |

Pembrolizumab + FOLFOX (n=1); pembrolizumab (n=1); nivolumab + ipilimumab (n=1) |

pCR (n=1); cCR (n=1); cCR (n=1) |

TME (n=1); Watch and Wait (n=2) |

12 |

| Mans L et al. (12), 2020 | 1 | III | Loss of MSH2 (n=1) | No | Nivolumab + ipilimumab and then nivolumab adjuvant (n=1) | cCR and pCR (n=1) | TME (n=1) | 6 |

| Liu DX et al. (13), 2020 | 4 | III | dMMR (n=4) | No | Pembrolizumab + CAPOX (n=1); pembrolizumab + ipilimumab (n=1); nivolumab (n=1); pembrolizumab (n=1) |

cPR and pCR (n=1); cCR (n=1); cPR and pCR (n=1); cPR and pCR (n=1) |

TME (n=3); Watch and Wait (n=1) | NR |

| Trojan J et al. (14), 2021 | 1 | III | Loss of MSH2 and MSH6 (n=1) | No | Nivolumab + ipilimumab (n=1) | cCR and pCR (n=1) | TME | NR |

| Wang Q et al. (15), 2021 | 10 | I (n=1); II (n=3); III (n=6) |

dMMR (n=10) | No | Anti PD-1 (NR) | cCR (n=10) | Watch and Wait (n=10) | 11.6 |

MSI-H/dMMR, microsatellite instability-high/deficient mismatch repair; MMR, mismatch repair; FOLFOXIRI, fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin and irinotecan; cCR, clinical complete response; pCR, pathological complete response; TME, total mesorectal excision; FOLFOX, fluorouracil, oxaliplatin and leucovorin; CRT, chemoradiotherapy; CAPOX, capecitabine and oxaliplatin; PD-1, anti-programmed death-1; NR, not reported.

Considering the evidence in case reports and phase II trials of ICIs in the neoadjuvant setting, we highlight that the existence of a discordant radiologic and complete response of the rectal wall and remnant LN has not been previously reported before our case report. Regarding our case findings, we have found in the literature that rectal cancers with a pCR in the rectal wall (ypT0N0) after preoperative ChT may still present positive LNs or tumor deposits in 7–13.6% of the studied cases (19,20). However, there is limited knowledge about the heterogeneity of ICIs responses in rectal cancer. Uncommon patterns of response, such as pseudoprogression, slow tumoral response, or hyperprogression, have been reported with immunotherapy mainly in melanoma, lung, and colon cancer. Pseudoprogression has been defined as an increase in the size of the primary tumor or the appearance of a new lesion, followed by tumor regression or stabilization (21). Specifically, for ICIs, Immune-based Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (iRECIST) guidelines incorporated the category of “unconfirmed progressive disease” (iUPD) to include the radiological progression of lesions or new lesions that have not been confirmed by a new image at least four to eight weeks after the initial scan. Immunotherapy continuation is normally recommended in current guidelines until disease progression is confirmed (iCPD) in a new scan (22). In a retrospective cohort, Colle et al. reported that pseudoprogression occurs in approximately 10% of patients with MSI-H/dMMR metastatic CRCs treated with ICIs. The authors highlighted that this phenomenon was commonly observed during the first three months of treatment. In their cohort, pseudoprogression occurred more frequently in patients treated with anti-PD-1 monotherapy than in those receiving the combination of anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 agents (23). As far as our case is concerned, we asked whether the existence of pseudoprogression may be considered based on pathological findings rather than strict radiological criteria. Most likely, a new MRI performed 4–8 weeks after the initial scan would have supported the occurrence of pseudoprogression.

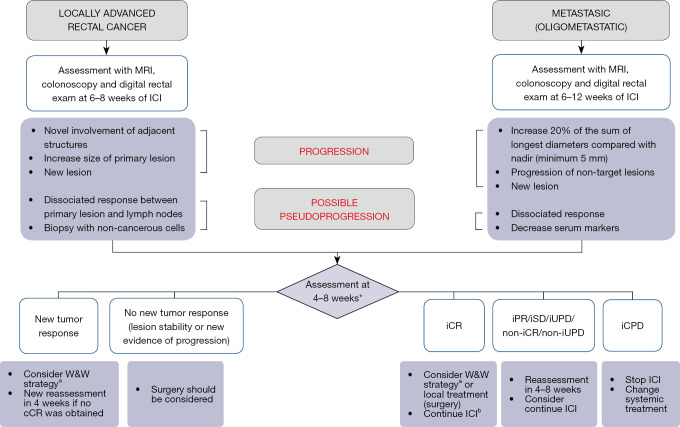

With all the above-mentioned factors, we argue that our case highlights the need to review the current workup of atypical responses in immunotherapy-treated rectal cancer and to discuss the optimal duration of treatment before deciding on a definitive treatment. Therefore, we propose a potential algorithm for tumor reassessments in this specific scenario (Figure 2). Our considerations were based on the opinion of a local multidisciplinary group and should be taken with caution due to the lack of prospective evidence.

Figure 2.

A potential algorithm for assessment of MSI-H/dMMR rectal cancer treated with immunotherapy, and the suspicion of pseudoprogression. *, assessment with MRI, colonoscopy and digital rectal exam. a, in those patients who achieve a clinical complete response with no evidence of residual disease on digital rectal examination, rectal MRI and direct endoscopic evaluation, may be considered in centers with experienced multidisciplinary teams; b, continue ICI until 2 years. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; W&W, watch-and-wait; cCR, clinical complete response; MSI-H/dMMR, microsatellite instability-high/deficient mismatch repair. Prefix “i” indicates immune response assigned using iRECIST: iCR, complete response; iPR, partial response; iSD, stable disease; iUPD, unconfirmed progressive disease; non-iCR, no complete response; non-iUPD, unconfirmed progressive disease; iCPD, confirmed progressive disease.

In LARC, we proposed an initial assessment with MRI, colonoscopy, and digital rectal exam at 6–8 weeks after ICI initiation, in agreement with current guidelines. Some characteristics, such as novel involvement of adjacent structures, increased the size of primary lesions, and the evidence of new lesions would typically be considered disease progression according to the current RECIST 1.1 Criteria. Nevertheless, we consider that certain characteristics may reflect the possibility of pseudoprogressive disease, including the existence of a dissociated response between the primary tumor and regional LN or the absence of cancerous cells in a new biopsy. As a consequence, and suspecting a pseudoprogression pattern, a new reassessment after 4–8 weeks is proposed. Watchful waiting strategies may be offered if a new tumor response is observed. On the other hand, in the case of progressive disease, surgery might be indicated. Finally, although a matter of debate, if only lesion stability is observed, surgical management should be considered on a case-by-case basis.

In the oligometastatic scenario, an initial reassessment is proposed at 6–12 weeks of ICI initiation. The suspicion of pseudoprogression is consistent with other tumor models, according to iRECIST guidelines. Specifically, the existence of dissociated responses and the decrease in serum markers may account for additional hints in this tumor model. In this case, a reassessment after 4–8 weeks should be offered. Furthermore, in the advanced scenario, we proposed that if no further disease progression is observed, treatment should be continued. Surgery might only be recommended in specific situations, such as local unequivocal radiological progression or clinical progression. Notably, for selected cases, a tumor biopsy may be offered at the moment of disease reevaluation to distinguish pseudoprogressive from true progressive disease. Additionally, novel approaches using circulating tumor DNA by analyzing minimal residual disease could be particularly useful under this circumstance.

Conclusions

Following the increasing use of ICIs for treating MSI-H/dMMR CRCs, the improvement in current guidelines for tumor assessments in this scenario represents a novel challenge. A careful evaluation by a multidisciplinary tumor board is crucial, and atypical responses should be taken into consideration for treatment personalization. The optimal strategy and sequence of therapy for dMMR/MSI-H LARC remain to be elucidated, and immunotherapy appears to be positioned as an important player in this field.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Footnotes

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-22-1140/rc

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-22-1140/coif). FE reports that he has participated in advisory boards of NUTRICIA, and received support for conferences from BMS, ROCHE, MERCK, AMGEN, PFIZER, RAFFO, and SERVIER. He also reports to have attended medical meetings supported by VARIFARMA. LB reports that she has been honoraria of Roche, Janssen Oncology, MSD Oncology, AstraZeneca, AMGEN, and Pfizer. She has been a consultant or advisor for MSD Oncology, AstraZeneca, and Merck. She has been speaker for Roche and Janssen Oncology. She also claims to have received research funding from Roche (payment to Alexander Fleming Institute), travel, accommodation and expenses from Bayer, Novartis, Ellea, and Pfizer. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Koopman M, Kortman GA, Mekenkamp L, et al. Deficient mismatch repair system in patients with sporadic advanced colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 2009;100:266-73. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.André T, Shiu KK, Kim TW, et al. Pembrolizumab in Microsatellite-Instability-High Advanced Colorectal Cancer. N Engl J Med 2020;383:2207-18. 10.1056/NEJMoa2017699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanani A, Veen T, Søreide K. Neoadjuvant immunotherapy in primary and metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 2021;108:1417-25. 10.1093/bjs/znab342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hupkens BJP, Martens MH, Stoot JH, et al. Quality of Life in Rectal Cancer Patients After Chemoradiation: Watch-and-Wait Policy Versus Standard Resection - A Matched-Controlled Study. Dis Colon Rectum 2017;60:1032-40. 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu S, Jiang T, Xiao L, et al. Total Neoadjuvant Therapy (TNT) versus Standard Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Oncologist 2021;26:e1555-66. 10.1002/onco.13824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cercek A, Lumish M, Sinopoli J, et al. PD-1 Blockade in Mismatch Repair-Deficient, Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. N Engl J Med 2022;386:2363-76. 10.1056/NEJMoa2201445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009;45:228-47. 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mandard AM, Dalibard F, Mandard JC, et al. Pathologic assessment of tumor regression after preoperative chemoradiotherapy of esophageal carcinoma. Clinicopathologic correlations. Cancer 1994;73:2680-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel UB, Taylor F, Blomqvist L, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging-detected tumor response for locally advanced rectal cancer predicts survival outcomes: MERCURY experience. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:3753-60. 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.9068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang J, Cai J, Deng Y, et al. Complete response in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer after neoadjuvant treatment with nivolumab. Oncoimmunology 2019;8:e1663108. 10.1080/2162402X.2019.1663108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demisse R, Damle N, Kim E, et al. Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy-Based Systemic Treatment in MMR-Deficient or MSI-High Rectal Cancer: Case Series. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2020;18:798-804. 10.6004/jnccn.2020.7558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mans L, Pezzullo M, D'Haene N, et al. Pathological complete response after neoadjuvant immunotherapy for a patient with microsatellite instability locally advanced rectal cancer: should we adapt our standard management for these patients? Eur J Cancer 2020;135:75-7. 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.04.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu DX, Li DD, He W, et al. PD-1 blockade in neoadjuvant setting of DNA mismatch repair-deficient/microsatellite instability-high colorectal cancer. Oncoimmunology 2020;9:1711650. 10.1080/2162402X.2020.1711650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trojan J, Stintzing S, Haase O, et al. Complete Pathological Response After Neoadjuvant Short-Course Immunotherapy with Ipilimumab and Nivolumab in Locally Advanced MSI-H/dMMR Rectal Cancer. Oncologist 2021;26:e2110-e2114. 10.1002/onco.13955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Q, Xiao B, Jiang W, et al. P-187 Watch-and-wait strategy for DNA mismatch repair-deficient/microsatellite instability-high rectal cancer with a clinical complete response after neoadjuvant immunotherapy: An observational cohort study. Ann Oncol 2021;32:S163-S164. 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.05.242 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yuki S, Bando H, Tsukada Y, et al. Short-term results of VOLTAGE-A: Nivolumab monotherapy and subsequent radical surgery following preoperative chemoradiotherapy in patients with microsatellite stable and microsatellite instability-high locally advanced rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:4100. 10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.4100 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin Z, Cai M, Zhang P, et al. Phase II, single-arm trial of preoperative short-course radiotherapy followed by chemotherapy and camrelizumab in locally advanced rectal cancer. J Immunother Cancer 2021;9:e003554. 10.1136/jitc-2021-003554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salvatore L, Bensi M, Corallo S, et al. Phase II study of preoperative (PREOP) chemoradiotherapy (CTRT) plus avelumab (AVE) in patients (PTS) with locally advanced rectal cancer (LARC): The AVANA study. J Clin Oncol 2021;39:3511. 10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.3511 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagtegaal ID, Glynne-Jones R. How to measure tumour response in rectal cancer? An explanation of discrepancies and suggestions for improvement. Cancer Treat Rev 2020;84:101964. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2020.101964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guillem JG, Chessin DB, Cohen AM, et al. Long-term oncologic outcome following preoperative combined modality therapy and total mesorectal excision of locally advanced rectal cancer. Ann Surg 2005;241:829-36; discussion 836-8. 10.1097/01.sla.0000161980.46459.96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma Y, Wang Q, Dong Q, et al. How to differentiate pseudoprogression from true progression in cancer patients treated with immunotherapy. Am J Cancer Res 2019;9:1546-53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seymour L, Bogaerts J, Perrone A, et al. iRECIST: guidelines for response criteria for use in trials testing immunotherapeutics. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:e143-52. 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30074-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colle R, Radzik A, Cohen R, et al. Pseudoprogression in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors for microsatellite instability-high/mismatch repair-deficient metastatic colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer 2021;144:9-16. 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The article’s supplementary files as