Summary

Background

Hearing loss (HL) is a leading cause of disability worldwide, but its clinical consequences and population burden have been incompletely studied.

Methods

We did a retrospective population-based cohort study of 4,724,646 adults residing in Alberta between April 1, 2004 and March 31, 2019, of whom 152,766 (3.2%) had HL identified using administrative health data. We used administrative data to identify comorbidity and clinical outcomes, including death, myocardial infarction, stroke/transient ischemic attack, depression, dementia, placement in long-term care (LTC), hospitalization, emergency visits, pressure ulcers, adverse drug events and falls. We used Weibull survival models (binary outcomes) and negative binomial models (rate outcomes) to compare the likelihood of outcomes in those with vs without HL. We calculated population-attributable fractions to estimate the number of binary outcomes associated with HL.

Findings

The age-sex-standardized prevalence of all 31 comorbidities at baseline was higher among participants with HL than those without. Over median follow-up of 14.4 y and after adjustment for potential confounders at baseline, participants with HL had higher rates of days in hospital (rate ratio 1.65, 95% CI 1.39, 1.97), falls (RR 1.72, 95% CI 1.59, 1.86), adverse drug events (RR 1.40, 95% CI 1.35, 1.45), and emergency visits (RR 1.21, 95% CI 1.14, 1.28) compared to those without, and higher adjusted hazards of death, myocardial infarction, stroke/transient ischemic attack, depression, heart failure, dementia, pressure ulcers and LTC placement. The estimated number of people with HL who required new LTC placement annually in Canada was 15,631, of which 1023 were attributable to HL. Corresponding estimates for new dementia among people with HL were 14,959 and 4350, and for stroke/TIA the estimates were 11,582 and 2242.

Interpretation

HL is common, is often accompanied by substantial comorbidity, and is associated with significant increases in risk for a broad range of adverse clinical outcomes, some of which are potentially preventable. This high population health burden suggests that increased and coordinated investment is needed to improve the care of people with HL.

Funding

Canadian Institutes of Health Research; David Freeze chair in health services research.

Keywords: Hearing loss, Epidemiology

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

What is the burden of comorbidity among community-dwelling people with hearing loss, and what is the excess risk of patient-important outcomes among people with this common chronic condition?

Added value of this study

This population-based study of >4 million people demonstrates that hearing loss is associated with a high burden of comorbidity as well as substantial increases in a broad range of adverse outcomes including cardiovascular events, hospitalization, placement in long-term care, emergency visits and adverse drug events.

Implications of all the available evidence

The high burden of serious illness among people with HL and the potential for early intervention to improve outcomes argue in favor of increased investment aimed at preventing HL while improving health care for those already affected.

Introduction

Hearing loss (HL) affects nearly 1.6 billion people and is the third-leading cause of disability worldwide.1, 2, 3 Since the prevalence of HL increases with age, its global impact is expected to increase in parallel with population aging.4 HL is independently associated with increased mortality and the risk of incident dementia,5, 6, 7, 8 but less is known about the association between hearing loss and other patient-important outcomes such as cardiovascular disease, hospitalization, or placement in long-term care facilities. In addition, the burden of chronic disease and other comorbidity among people with hearing loss has been incompletely studied.9 Finally, although the potential for communication barriers between people with HL and their care providers is clear, whether people with HL are at excess risk of potentially preventable outcomes such as adverse drug events, pressure ulcers, or emergency department visits is less so. This information would be potentially useful for decision-makers who seek to understand the current and projected population health burden associated with HL, and may guide the design of interventions that aim to improve care for people with this condition.

We designed this population-based study of people treated in a universal health system to investigate the association between HL and a broad range of clinical outcomes. Important secondary objectives were to describe the burden of comorbidities observed among people with HL, and to identify clinical factors that might modify any association between HL and adverse outcomes.

Methods

We reported this retrospective population-based cohort study according to the STROBE guidelines.10 The institutional review boards at the Universities of Alberta (Pro 00053469) and Calgary (REB16-1575) approved the study and waived the requirement for participants to provide consent.

Data sources and cohort

We used an existing database, which incorporates patient registry, physician claims, hospitalizations, and ambulatory care utilization data from all adults registered with the provincial health ministry in Alberta, Canada; and links them with data from provincial clinical laboratories. This database has been widely used11, 12, 13 because of its population-based coverage of a geographically defined area, including demographic characteristics, health services utilization, and clinical outcomes. Additional information on the database is available elsewhere, including the validation of selected data elements.14 All Alberta residents are eligible for insurance coverage by Alberta Health with >99% registered as participants. The database was used to assemble cohorts of adults who resided in Alberta, Canada between April 1, 2004 and March 31, 2019. The index date was April 1, 2004, the day of first contact with Alberta Health, or the participants’ 18th birthday, whichever was latest.

Hearing loss, comorbidities, and other characteristics

We created an algorithm to identify participants with HL using provider claims, at least two claims 30 days apart. This algorithm has not been validated but is based on those used in prior studies.15,16 We created a second algorithm for hearing loss using one hospitalization or two provider claims within 2 years. Eligible ICD-9, ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CA codes are found in Supplemental Table S1.

We classified each participant with respect to the presence or absence of 31 chronic conditions at baseline (lookback extended as far as April 1994 where records were available).17

We defined 26 of these morbidities using a previously published framework of validated algorithms as applied to Canadian provider claims, hospitalizations, and ambulatory care data, each of which had positive predictive values ≥70% as compared to a gold standard measure such as chart review.18 Morbidities included atrial fibrillation, alcohol misuse, asthma, cancer (lymphoma, all metastatic cancers, non-metastatic breast, cervical, colorectal, pulmonary, and prostate cancer), chronic heart failure, chronic pain, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic liver disease (viral hepatitis B, cirrhosis), severe constipation, dementia, depression, diabetes, epilepsy, hypertension, hypothyroidism, inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, multiple sclerosis, coronary artery disease (defined as myocardial infarction, coronary bypass artery graft, percutaneous coronary intervention), Parkinson's disease, peptic ulcer disease, peripheral artery disease, psoriasis, rheumatic diseases, schizophrenia and stroke or transient ischemic attack. Detailed methods for classifying comorbidity status and the specific algorithms used have been previously detailed.18 We defined gout, fragility fractures (wrist, forearm, spine, hip, humerus, and pelvis), and osteoporosis using similarly validated administrative algorithms.19,20 We defined severe obesity (body mass index [BMI] >35 kg/m2 before January 1, 2017 and BMI >40 kg/m2 after January 1, 2017) using a fee modifier as in our previous work.21 We defined severe chronic kidney disease by sustained estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 and/or registration with a provincial kidney replacement program.

As in our prior work, we used administrative data to identify age, biological sex, and rural residence location.22 We included the Pampalon index of material deprivation,23,24 which uses residential postal code to categorize participants into five categories of socioeconomic inequalities in health care services and population health with five representing the most deprived neighbourhoods.

Outcomes

We assessed all-cause mortality, and the first occurrence during follow-up of myocardial infarction,18,25 stroke or transient ischemic attack,18,26 or depression episode.18,27 Depression episodes were allowed to occur at most every 2 years. We also assessed new (not present at baseline) heart failure,18,27 dementia,18,27 and long-term care placement. We also assessed length of hospital stays, number of emergency visits, adverse drug events,28 pressure ulcers28 and falls.28 Emergency visits were also categorized as “preventable”, “low acuity” and “other” according to work by Gruneir et al.29

Statistical analyses

All analyses were done using Stata MP 17·0 (www.stata.com). We reported baseline descriptive statistics as counts and percentages, or means with standard deviations. We used time-to-event Weibull survival models to determine the hazard ratios of binary outcomes by hearing loss (HL) status (yes or no). We used negative binomial models to determine rate ratios of count outcomes by HL status, with an offset term of the natural logarithm for days of follow-up and modeled participants as a random intercept. We treated HL as a time-varying covariate, and thus events occurring any time within the study period prior to HL were included in the no-HL group and after hearing loss in the HL group. We divided participants into age-sex strata where age was grouped into 5-year intervals. In the Weibull modal, we modeled age-sex strata using shared frailty with a gamma distribution. In the negative binomial models, we estimated variances using the clustered sandwich estimator on the age-sex strata.

We adjusted for baseline or time-varying neighbourhood material deprivation quintile, rural residence and the 31 morbidities, in separate models. We determined that the proportional hazard assumption was satisfied by examining plots of the log-negative-log of within-group survivorship probabilities versus log-time for the Weibull models and we determined that the proportional rate assumption was satisfied by examining rate plots for the negative binomial models. We report the number, percentage or rate (per 100 patient-years) of events, and the age-sex adjusted, the baseline fully adjusted and time-varying fully adjusted hazard ratios (HR) or rate ratios (RR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). Additionally we report the annual number of cases, population attributable fraction,30 and the annual number of cases attributable to HL for the binary outcomes in Alberta, using data from the time-varying fully adjusted models to estimate the population attributable fraction. We also estimated the annual number of cases and the annual number of cases attributable to HL in Canada, assuming that the results from Alberta were applicable to other Canadian provinces and using 2022 population data from StatCan.31 We deemed two-sided p values <0.05 to be statistically significant.

Missing values occurred in the following variables: residence location (13.3%), material deprivation quintile (14.6%), and obesity (26.9%). For the purposes of modelling, we used indicator variables to represent missingness.

Sensitivity analyses

We explored whether certain characteristics (age categorized as 18–<50 y, 50–<70 y, and ≥70 y; biological sex; number of morbidities categorized as 0, 1–3 and ≥4) were potential modifiers of the association between hearing loss and four clinical outcomes with large effect sizes, using interaction terms. We also considered a second algorithm defining hearing loss.

Role of funding

The study was supported by MT's David Freeze Chair in Health Services Research at the University of Calgary. The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; nor in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Results

Cohort

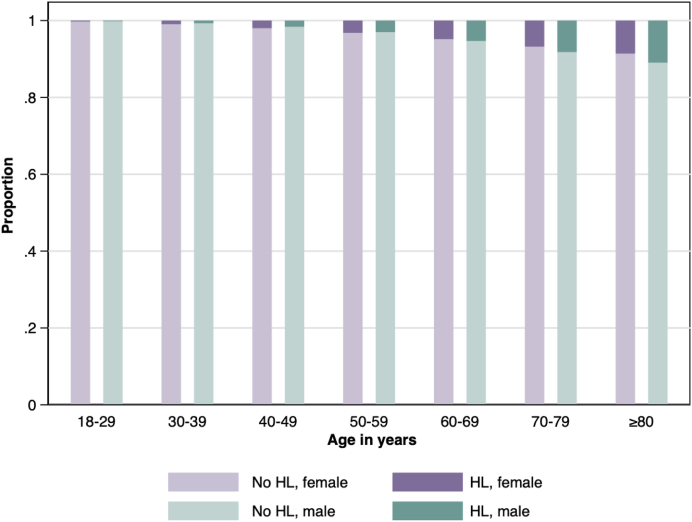

We identified 4,724,646 adult participants during the study period, of whom 94% had at least one encounter during follow-up. At baseline, 78,172 (1.7%) had HL and 74,594 (1.6%) received a new HL diagnosis during follow-up, yielding a total of 152,766 (3.2%) participants with HL. As expected, the prevalence of HL increased with age (Fig. 1) and increased over time: from 2.4% in 2004 to 2.9% in 2018.

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of hearing loss, by biological sex and age. HL, Hearing loss. Each participant's age has been classified into one of 7 categories: 18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–70, and ≥80 years. The heights of the bars depict the percentage of participants with and without hearing loss by age group and biological sex.

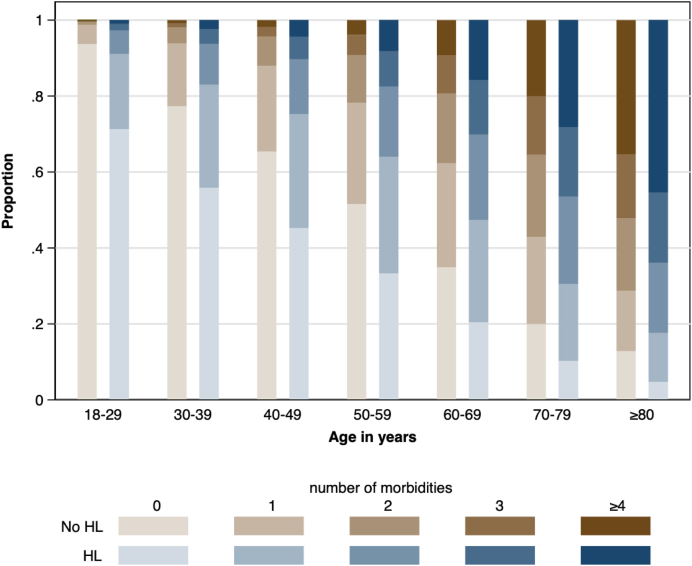

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study population at baseline. For participants with HL, the mean age was 52.4 years and 50.0% were female compared to a mean age of 36.5 and 49% female for those without HL. The total number of comorbidities (Fig. 2) and the prevalence of each comorbidity (Table 1) were higher in participants with HL than those without. All comorbidities remained more prevalent in those with HL after standardization for age and sex. The most frequent morbidities for participants with HL were hypertension (26.8%), chronic pain (19.7%), obesity (13.2%), depression (10.8), and chronic pulmonary disease (9.6%). After standardization for age and sex, participants with HL were followed by more physicians (mean 4.1 vs 2.5) and more physician types (mean 2.3] vs 1.4) than those without, and were more likely to have a mental health condition (10.0% vs 5.0%, p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline by hearing loss status.

| Characteristics |

Not standardized for age-sex strata |

Standardized for age-sex strata |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hearing loss | No hearing loss | Hearing loss | No hearing loss | |

| N | 152,766 | 4,571,880 | ||

| Age, ya | 52.4 [17.5] | 36.5 [17.1] | – | – |

| Male | 76,453 (50.0) | 2,332,302 (51.0) | – | – |

| Rural residence | 15,041 (10.1) | 413,313 (10.3) | 13,554 (9.3) | 414,005 (10.4) |

| Material deprivationa | 3.1 [1.4] | 3.2 [1.4] | 3.1 [1.5] | 3.2 [1.4] |

| Morbidities | ||||

| Obesity | 18,333 (13.2) | 338,895 (11.6) | 16,383 (12.2) | 340,470 (11.6) |

| Hypertension | 40,959 (26.8) | 408,808 (8.9) | 32,704 (21.7) | 418,317 (9.2) |

| Chronic pain | 30,143 (19.7) | 337,071 (7.4) | 24,922 (16.5) | 342,275 (7.5) |

| Depression | 16,461 (10.8) | 208,424 (4.6) | 14,052 (9.3) | 210,523 (4.6) |

| Diabetes | 11,663 (7.6) | 132,681 (2.9) | 9669 (6.4) | 135,233 (3.0) |

| Chronic pulmonary | 14,686 (9.6) | 138,431 (3.0) | 11,647 (7.7) | 141,100 (3.1) |

| Hypothyroid | 10,997 (7.2) | 113,098 (2.5) | 8762 (5.8) | 115,342 (2.5) |

| Osteoporosis | 10,604 (6.9) | 94,511 (2.1) | 8241 (5.5) | 96,571 (2.1) |

| Gout | 7142 (4.7) | 74,502 (1.6) | 5721 (3.8) | 76,221 (1.7) |

| Stroke/TIA | 7165 (4.7) | 59,398 (1.3) | 5650 (3.7) | 60,635 (1.3) |

| Fragility fracture | 3956 (2.6) | 49,223 (1.1) | 3168 (2.1) | 49,972 (1.1) |

| Cancer | 4285 (2.8) | 41,989 (0.9) | 3452 (2.3) | 42,858 (0.9) |

| Chronic heart failure | 4746 (3.1) | 46,889 (1.0) | 3871 (2.6) | 47,685 (1.0) |

| Alcohol misuse | 2396 (1.6) | 43,152 (0.9) | 2072 (1.4) | 43,573 (1.0) |

| Asthma | 3801 (2.5) | 42,472 (0.9) | 3052 (2.0) | 43,061 (0.9) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 4108 (2.7) | 35,914 (0.8) | 3261 (2.2) | 36,656 (0.8) |

| Coronary artery d. | 4343 (2.8) | 37,322 (0.8) | 3350 (2.2) | 38,337 (0.8) |

| Irritable bowel s. | 3040 (2.0) | 26,157 (0.6) | 2374 (1.6) | 26,625 (0.6) |

| Epilepsy | 1801 (1.2) | 22,860 (0.5) | 1533 (1.0) | 23,113 (0.5) |

| Rheumatic d. | 2746 (1.8) | 23,570 (0.5) | 2109 (1.4) | 24,094 (0.5) |

| Dementia | 1703 (1.1) | 19,662 (0.4) | 1484 (1.0) | 19,829 (0.4) |

| Schizophrenia | 1150 (0.8) | 18,571 (0.4) | 973 (0.6) | 18,786 (0.4) |

| Severe constipation | 1118 (0.7) | 10,310 (0.2) | 917 (0.6) | 10,456 (0.2) |

| Inflammatory bowel d. | 1200 (0.8) | 15,612 (0.3) | 987 (0.7) | 15,828 (0.3) |

| Multiple sclerosis | 758 (0.5) | 10,969 (0.2) | 606 (0.4) | 11,154 (0.2) |

| Peripheral arterial d. | 1026 (0.7) | 9240 (0.2) | 800 (0.5) | 9412 (0.2) |

| Psoriasis | 649 (0.4) | 7737 (0.2) | 523 (0.3) | 7886 (0.2) |

| Parkinson's d. | 732 (0.5) | 7812 (0.2) | 583 (0.4) | 7936 (0.2) |

| Severe CKD | 360 (0.2) | 4008 (0.1) | 316 (0.2) | 4043 (0.1) |

| Peptic ulcer d. | 341 (0.2) | 3443 (0.1) | 277 (0.2) | 3493 (0.1) |

| Liver d. | 182 (0.1) | 2995 (0.1) | 163 (0.1) | 3016 (0.1) |

| Complexity markers | ||||

| Number of morbiditiesa | 1.3 [1.6] | 0.4 [1.0] | 1.0 [1.5] | 0.5 [1.0] |

| Mental health condition | 18,486 (11.8) | 247,447 (5.3) | 15,800 (10.4) | 249,964 (5.4) |

| Number of prescriptionsa | 0.3 [3.4] | 1.0 [6.0] | 1.0 [6.1] | 1.0 [5.9] |

| Types of physiciansa | 2.3 [1.7] | 1.4 [1.3] | 2.3 [1.7] | 1.4 [1.3] |

| Number of physiciansa | 4.0 [3.7] | 2.5 [3.0] | 4.1 [3.7] | 2.5 [3.0] |

CKD, Chronic kidney disease; d, Disease; s, Syndrome; SD, Standard deviation; TIA, Transient ischemic attack.

N (%) or mean [SD] as appropriate. All characteristics were obtained at baseline. Participants in the group with hearing loss developed hearing loss at some point during follow-up. The age-sex strata are created using 5-year intervals of age. The differences between the groups were tested by regressing hearing loss onto each covariate in term, not weighted or weighted by age-sex strata, using logistic regression. All differences were significant at p < 0.001 except for the following: rural residence had a p = 0.007 for percentages that were not standardized for age-sex strata, and number of prescriptions had a p = 0.85 for means that were standardized for age-sex strata.

Mean [SD].

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of comorbidity among people with and without hearing loss, by age. HL, Hearing loss. Each participant's number of morbidities has been classified into one of 5 categories: none, 1 through 3, or 4 or more morbidities, and each participant's age has been classified into one of 7 groups: 18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–70, and ≥80 years. The heights of the bars depict the percentage of participants who fall into each morbidity category by hearing loss status and age group.

Clinical outcomes

During median follow-up of 14.4 years, 7.0% of participants (with or without hearing loss) died, 20.6% experienced an episode of depression, 4.7% experienced a stroke or a transient ischemic attack, 3.4% developed heart failure, 2.9% developed dementia, 1.4% had a myocardial infarction, and 1.3% were placed into longterm care (Table 2). Participants spent 78.9 days in hospital per 100 patient-years (100py). There were 41.9 emergency department visits per 100py, 0.37 falls per 100py, 0.33 adverse drug events per 100py, and 0.019 pressure ulcers per 100py.

Table 2.

Clinical outcomes by hearing loss status.

| Outcome | Hearing loss | No hearing loss | Age-sex adjusted (baseline) | Fully adjusted (baseline) | Fully adjusted (time-varying) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events (%) | (95% CI) | ||||

| All-cause mortality | 25,206 (16.5) | 304,391 (6.7) | 1.79 (1.76, 1.81) | 1.25 (1.23, 1.27) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.02) |

| Acute MI | 4904 (3.2) | 63,283 (1.4) | 1.42 (1.38, 1.47) | 1.10 (1.07, 1.13) | 1.03 (0.997, 1.06) |

| Stroke/TIA | 18,248 (12.2) | 201,441 (4.4) | 1.82 (1.80, 1.85) | 1.37 (1.35, 1.39) | 1.24 (1.22, 1.26) |

| Depression | 37,717 (27.6) | 935,758 (20.4) | 2.10 (1.98, 2.22) | 1.48 (1.40, 1.57) | 1.16 (1.14, 1.17) |

| New heart failure | 13,667 (9.3) | 145,881 (3.2) | 1.73 (1.70, 1.76) | 1.27 (1.25, 1.29) | 1.10 (1.08, 1.12) |

| New dementia | 15,177 (10.1) | 122,619 (2.7) | 2.16 (2.12, 2.20) | 1.61 (1.59, 1.64) | 1.41 (1.38, 1.43) |

| New LTC placement | 7204 (4.7) | 55,500 (1.2) | 1.91 (1.82, 2.00) | 1.46 (1.39, 1.53) | 1.07 (1.04, 1.10) |

| Events (rate/100py) | RR (95% CI) | ||||

| Days in hospital | 3,152,557 (204.4) | 37,802,674 (75.1) | 5.50 (3.50, 8.62) | 1.65 (1.39, 1.97) | 1.33 (1.16, 1.52) |

| Emergency visits | 1,025,983 (66.5) | 20,711,479 (41.1) | 1.65 (1.51, 1.79) | 1.21 (1.14, 1.28) | 1.14 (1.11, 1.18) |

| Potentially preventable | 236,743 (15.3) | 3,694,971 (7.3) | 2.47 (2.16, 2.81) | 1.37 (1.29, 1.47) | 1.12 (1.08, 1.17) |

| Low acuity | 66,029 (4.3) | 1,001,485 (2.0) | 2.79 (2.43, 3.19) | 1.63 (1.51, 1.75) | 1.15 (1.09, 1.22) |

| Other | 723,211 (46.9) | 16,015,023 (31.8) | 1.42 (1.33, 1.51) | 1.09 (1.05, 1.13) | 1.11 (1.08, 1.15) |

| Adverse drug events | 12,080 (0.8) | 157,941 (0.3) | 3.05 (2.52, 3.70) | 1.40 (1.35, 1.45) | 1.08 (1.04, 1.12) |

| Pressure ulcer | 716 (0.05) | 9244 (0.02) | 1.14 (0.89, 1.38) | 1.39 (1.21, 1.60) | 0.97 (0.85, 1.11) |

| Fall | 17,252 (1.1) | 173,942 (0.3) | 4.20 (3.27, 5.40) | 1.72 (1.59, 1.86) | 1.28 (1.21, 1.35) |

MI, Myocardial infarction; HR, Hazard ratio; LTC, Long-term care; PY, Patient-year; RR Rate ratio; TIA, Transient ischemic attack.

All models treat HL as a time-varying covariate, and thus events occurring any time within the study period prior to HL were included in the no-HL group and after hearing loss in the HL group.

We divided participants into age-sex strata where age was grouped into 5-year intervals. In the Weibull model, HR or RR (95% CI) are reported as appropriate. All-cause mortality, AMI, stroke/TIA, new HF (in those without heart failure), new dementia (in those without dementia) and new LTC placement (in those not in care) were regressed on time-varying hearing loss using Weibull regression with shared frailty modelled in 5-year age and sex groups. Length of hospital stays, ED visits, ADEs, pressure ulcers, and falls were regressed on time-varying hearing loss using negative binomial regression where the clustered sandwich estimator was used for variance estimation in the 5-year age and sex groups.

The other two models were further adjusted for rural residence status, material deprivation quintiles, obesity, hypertension, chronic pain, depression, chronic pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, osteoporosis, gout, stroke or TIA, fragility fractures, heart failure, cancer, asthma, alcohol misuse, coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, irritable bowel syndrome, rheumatic diseases, epilepsy, dementia, schizophrenia, inflammatory bowel disease, multiple sclerosis, severe constipation, peripheral artery disease, Parkinson's disease, psoriasis, severe chronic kidney disease, peptic ulcer disease, and chronic liver disease.

The adjusted (baseline) model used these covariates as assessed at baseline, whereas the adjusted (time-varying) model updated the covariates throughout follow-up.

Bold values indicate statistically significant at p < 0.05.

After adjustment for age and sex, participants with HL experienced substantially more adverse clinical outcomes than participants without HL (Table 2). The rate of hospitalization (total days) was 5.50 times higher (95% CI 3.50, 8.62), the rate of falls was 4.20 times higher (95% CI 3.27, 5.40), and of adverse drug events 3.05 times higher (95% CI 2.52, 3.70). Overall, the rate of emergency department visits was 1.65 times higher (95% CI 1.51, 1.79) in people with HL than without; the rates of low acuity and potentially preventable visits were both increased.

In fully adjusted models using baseline covariates, the risk of all-cause mortality, acute MI, stroke/TIA, depression, new heart failure, new dementia and new placement in LTC were all significantly more common in people with HL than those without. The magnitude of the excess risk ranged from hazard ratio (HR) 1.10 (95% CI 1.07, 1.13) for acute MI to rate ratio (RR) 1.72 (95% CI 1.59, 1.86) for falls. After adjustment for time-varying covariates, the magnitude of the excess risk or rate associated with HL was attenuated for all outcomes, and remained significant for the majority, although not for the risk of mortality, the risk of acute MI, or the rate of pressure ulcers. The second algorithm defining hearing loss had similar results (Supplemental Table S2).

Effect modification

We selected the clinical outcomes with the highest relative increases in events (risk of dementia, rate of hospital days, rate of falls, and risk of stroke or TIA) to explore age, sex, and number of morbidities as potential modifiers of the associations between HL and outcomes.

Age did not modify the association between HL and the rate of hospital days or the rate of falls, but significantly modified the associations between HL and the risk of dementia and the risk of stroke/TIA (p < 0.001), for which the magnitude of the excess risk associated with HL was greater for younger participants than older participants (Table 3). Biological sex modified the association between HL and all four outcomes: the magnitude of the excess risk associated with HL was greater in men than women for dementia, days in hospital and stroke/TIA (all p ≤ 0.002) but greater in women than men for falls (p = 0.01). The number of comorbidities also modified the association between HL and all four outcomes; the magnitude of the excess risk associated with HL was greater for participants with fewer comorbidities than those with more comorbidities (all p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Clinical outcomes by hearing loss status.

| Interaction | Stroke/TIA | New dementia | Days in hospital | Fall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | |||

| Age, y | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.98 | 0.14 |

| 18–<50 | 1.82 (1.71, 1.93) | 2.57 (2.23, 2.96) | 0.96 (0.64, 1.45) | 1.12 (0.90, 1.38) |

| 50–<70 | 1.17 (1.13, 1.20) | 1.45 (1.37, 1.52) | 1.09 (1.06, 1.12) | 1.01 (0.91, 1.12) |

| ≥70 | 1.03 (1.01, 1.05) | 1.10 (1.08, 1.12) | 0.95 (0.88, 1.04) | 1.01 (0.94, 1.08) |

| Sex | 0.002 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.01 |

| Female | 1.21 (1.19, 1.24) | 1.31 (1.28, 1.35) | 1.03 (0.88, 1.21) | 1.40 (1.29, 1.51) |

| Male | 1.27 (1.25, 1.30) | 1.54 (1.50, 1.58) | 1.87 (1.61, 2.18) | 1.16 (1.07, 1.27) |

| Number of morbidities | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 0 | 2.24 (2.12, 2.38) | 3.57 (3.23, 3.94) | 1.33 (1.02, 1.73) | 1.58 (1.33, 1.87) |

| 1–3 | 1.36 (1.33, 1.39) | 1.80 (1.75, 1.85) | 1.39 (1.21, 1.59) | 1.43 (1.33, 1.53) |

| ≥4 | 1.06 (1.04, 1.08) | 1.18 (1.15, 1.20) | 1.16 (1.09, 1.23) | 1.11 (1.06, 1.16) |

HR, Hazard ratio; RR, Rate ratio; TIA, Transient ischemic attack.

All models treat HL as a time-varying covariate, and thus events occurring any time within the study period prior to HL were included in the no-HL group and after hearing loss in the HL group.

HR or RR (95% CI) are reported as appropriate. Stroke/TIA and new dementia (in those without dementia) were regressed on time-varying hearing loss using Weibull regression and interacted with one of five potential modifiers (age categorized as 18–<50, 50–<70, and ≥70 years, sex, number of comorbidities categorized as 0, 1–3, or ≥4 morbidities) with shared frailty modelled in either 5-year age and sex groups, or simply age or sex groups, depending on the modifier. Length of hospital stays and falls were regressed on time-varying hearing loss using negative binomial regression and interacted with one of five potential modifiers where the clustered sandwich estimator was used for variance estimation in the 5-year age and sex groups, just age, or just sex groups.

The models were further adjusted for time-varying rural status, material deprivation quintiles, obesity, hypertension, chronic pain, depression, chronic pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, osteoporosis, gout, stroke or TIA, fragility fractures, heart failure, cancer, asthma, alcohol misuse, coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, irritable bowel syndrome, rheumatic diseases, epilepsy, dementia, schizophrenia, inflammatory bowel disease, multiple sclerosis, severe constipation, peripheral artery disease, Parkinson's disease, psoriasis, severe chronic kidney disease, peptic ulcer disease, and chronic liver disease.

Bold values indicate statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Population attributable risk

The population attributable risk associated with HL for the binary outcomes in our dataset ranged from 0.3% for new LTC placement to 3.8% for depression (Supplemental Table S3).

After extrapolation to the entire Canadian adult population, the estimated number of people with HL who require new LTC placement annually in Canada was 15,631, of which 1023 were attributable to HL. Corresponding estimates for new dementia were 14,959 and 4350 and for stroke/TIA the estimates were 11,582 and 2242.

Discussion

This population-based cohort study of more than 4 million adults treated in a universal health system had four key findings. First, even after adjustment for age and sex, HL is associated with a substantially increased burden of comorbidity. Second, HL is associated with excess risk for a broad range of adverse clinical outcomes, including substantial increases in the rates of potentially preventable outcomes such as hospitalization, LTC placement, emergency visits, adverse drug events and falls. Third, progressively more thorough adjustment for comorbidities at baseline and during follow-up tended to attenuate but not eliminate the excess risk associated with HL. Fourth, the magnitude of the excess risk associated with HL appeared to be higher in people who were otherwise at lower risk, such as those who were younger or had less comorbidity.

Previous work has identified HL as a strong risk factor for dementia7,32 and falls.33, 34, 35 HL has also been associated with above-average rates of all-cause mortality6,7 and hospitalization,36 an increased prevalence of comorbidity,37 and perhaps an excess risk of cardiovascular events.38,39 Prior research clearly shows that HL is common among people in LTC facilities, and one study suggests that among people receiving homecare, the presence of HL seems to hasten placement in a LTC facility.40 Studies examining the link between HL and emergency room visits,41 adverse drug reactions or pressure ulcers are less conclusive or have not been done. Although these prior studies were of high quality, they have typically included a much smaller sample size, could not adjust for comorbidity to the same extent, and were often done in populations without access to universal healthcare. Our study extends prior work by including a broad range of clinical outcomes over an extended follow-up period in a large population-based cohort, reducing the possibility of selection bias, ensuring complete capture of clinical outcomes during follow-up, and allowing us to estimate population attributable risk.

Why would HL be associated with excess risk? For outcomes such as adverse drug events, hospitalization and preventable emergency visits, we speculate that communication barriers between health professionals and patients are responsible. The independently increased risk of LTC placement warrants further investigation, since it might suggest that additional supports are required for people with HL to continue living independently despite their disability. The excess risk of falls may be due to increased cognitive load, reduced environmental awareness, or perhaps concomitant proprioceptive/vestibular dysfunction.34,42 For other outcomes such as stroke, the apparently increased risk may relate to residual confounding by comorbidities that are also associated with HL, such as hypertension or vascular disease. However, even for these outcomes it is plausible that people with HL do not always receive optimal treatment for these comorbidities due to communication challenges, provider bias,43,44 depression, or other barriers to care, which in turn warrants critical reflection about how best to improve equity and accessibility to health care services for people with HL. Even if some of the apparent excess risk is due to residual confounding by comorbidity, our data indicate that the presence of HL may be clinically useful as a marker for high risk of adverse outcomes.

The finding that the excess risk of adverse outcomes associated with HL was greater in participants who would otherwise be at lower risk due to younger age or fewer comorbidities not been previously reported to our knowledge. This effect modification was independent of multiple potential confounders, and may be due to the absence of competing risk factors in these healthier subgroups, although this explanation is speculative.

Our results together with the prior literature on this topic have two potential implications. First, research on the causes, consequences and optimal treatment of hearing loss is significantly underfunded. For example, in 2017 only 0.6% of the total National Institutes of Health budget was committed to grants on hearing loss research.45,46 This level of funding is not commensurate with the global burden of hearing loss, and additional investment is required. Second, the findings from this observational study do not demonstrate a causal link between HL and adverse outcomes. However, our results demonstrate that people with HL constitute a high-risk group that should arguably be prioritized for intervention, especially given the potentially preventable nature of many of the outcomes that we studied. The relatively large number of such outcomes that occur in people with HL (as well as the smaller but still substantial number that are attributable to HL) indicate that action is required in three broad areas: better care for people with HL who experience medical illness, including support for communication as well as management of comorbidity; better treatment and rehabilitation of HL specifically; and more effective public health actions to prevent HL.47 Our findings support the need for coordinated national strategies for ear and hearing care,48 with input from a broad range of stakeholders. Such strategies are widely available for conditions such as cancer or mental illness -- but not for ear and hearing care, which is a missed opportunity that must be addressed.

Our study has several important strengths, including the use of population-based data from a geographically defined area served by a universal health care system; large sample size and adequate follow-up time; use of validated algorithms for ascertaining the presence or absence of comorbidity; rigorous analytical methods; and inclusion of a broad range of clinically relevant and patient-important outcomes. However, our study also has limitations that should be considered when interpreting results. First, like all studies using administrative data, residual confounding is possible by unmeasured characteristics such as smoking, noise exposure, physical activity, diet, access to assistive devices such as hearing aids, or the availability of social supports. Second, although the large majority (94%) of participants had at least one encounter during follow-up, those with more encounters may have been more likely to be classified with HL and so ascertainment bias could have exaggerated the association between HL and adverse outcomes. Third, although we based our algorithm for HL on published studies using administrative data, it has not been validated against an independent standard such as audiological testing. To the extent that claims data may detect only more severe cases of HL, our findings likely underestimate the population health burden of HL. Third, the absolute effect size for some associations was statistically significant but clinically small. Finally, we studied people from a single Canadian province and our findings will require validation in other settings.

In conclusion, HL is a common condition that is associated with a high burden of comorbidity and substantial increases in a broad range of potentially preventable adverse outcomes including hospitalization, LTC placement, emergency visits, adverse drug events and falls. The high burden of serious medical illness among people with HL, the potential for early intervention to improve outcomes, and the relatively large absolute attributable burden of HL all argue in favor of increased investment aimed at preventing HL while improving health care for those already affected.

Contributions

MT conceived the study. NW did the statistical analyses. MT and NW wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the design, interpretation of results and critical revision of the article for intellectually important content. MT and NW had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Data sharing statement

We cannot make our dataset available to other researchers due to our contractual arrangements with the provincial health ministry (Alberta Health), who is the data custodian. Researchers may make requests to obtain a similar dataset at https://absporu.ca/research-services/service-application/.

Declaration of interests

TH is a (non-paid) board director for the Canadian Academy of Audiology. SWK is a director of the Real World Evidence Consortium, and the Alberta Drug and Therapeutic Evaluation Consortium (Universities of Alberta, Calgary, and Institute of Health Economics); these entities receive funding from decision makers and industry to conduct research. All research funding is made to the academic institution; investigator retains full rights of academic freedom and right to publish. This relationship is not related to the current work. Otherwise there were no potential conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

The authors of this report are grateful to Ghenette Houston for administrative support and Feng Ye for her technical review.

The study was supported by MT's David Freeze Chair in Health Services Research at the University of Calgary. The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; nor in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

This study is based in part by data provided by Alberta Health and Alberta Health Services. The interpretation and conclusions contained herein are those of the researchers and do not represent the views of the Government of Alberta or Alberta Health Services. Neither the Government of Alberta nor Alberta Health or Alberta Health Services express any opinion in relation to this study.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102068.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Mick P.T., Hamalainen A., Kolisang L., et al. The prevalence of hearing, vision, and dual sensory loss in older Canadians: an analysis of data from the Canadian longitudinal study on aging. Can J Aging. 2021;40(1):1–22. doi: 10.1017/S0714980820000070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tordrup D., Smith R., Kamenov K., et al. Global return on investment and cost-effectiveness of WHO's HEAR interventions for hearing loss: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2022;10(1):e52–e62. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00447-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . WHO; Geneva: 2021. World report on hearing. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goman A.M., Reed N.S., Lin F.R. Addressing estimated hearing loss in adults in 2060. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;143(7):733–734. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2016.4642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng X., Li W., Cheng M., et al. Association of hearing loss with total and cause-specific mortality in US adults. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2022;29(4):5032–5042. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-16038-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan B.K.J., Ng F.Y.C., Song H., Tan N.K.W., Ng L.S., Loh W.S. Associations of hearing loss and dual sensory loss with mortality: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of 26 observational studies with ,213,756 participants. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;148(3):220–234. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2021.3767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loughrey D.G., Kelly M.E., Kelley G.A., Brennan S., Lawlor B.A. Association of age-related hearing loss with cognitive function, cognitive impairment, and dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;144(2):115–126. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2017.2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Livingston G., Sommerlad A., Orgeta V., et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2673–2734. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall J.W. Promoting healthy hearing over the lifespan. Audit Vestib Res. 2021;30(2):74–94. [Google Scholar]

- 10.von Elm E., Altman D.G., Egger M., et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexander R.T., Hemmelgarn B.R., Wiebe N., et al. Kidney stones and kidney function loss: a cohort study. BMJ. 2012;345:e5287. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson S., James M., Wiebe N., et al. Cause of death in patients with reduced kidney function. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26(10):2504–2511. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014070714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tonelli M., Muntner P., Lloyd A., et al. Risk of coronary events in people with chronic kidney disease compared with those with diabetes: a population-level cohort study. Lancet. 2012;380(9844):807–814. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60572-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hemmelgarn B.R., Clement F., Manns B.J., et al. Overview of the Alberta kidney disease network. BMC Nephrol. 2009;10:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-10-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hung S.C., Liao K.F., Muo C.H., Lai S.W., Chang C.W., Hung H.C. Hearing loss is associated with risk of alzheimer's disease: a case-control study in older people. J Epidemiol. 2015;25(8):517–521. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20140147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deal J.A., Reed N.S., Kravetz A.D., et al. Incident hearing loss and comorbidity: a longitudinal administrative claims study. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(1):36–43. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2018.2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stevens P.E., Levin A. Kidney Disease: improving global outcomes chronic kidney disease guideline development work group members. Evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease: synopsis of the kidney disease: improving global outcomes 2012 clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(11):825–830. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-11-201306040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tonelli M., Wiebe N., Martin F., et al. Methods for identifying 30 chronic conditions: application to administrative data. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2015;15:31. doi: 10.1186/s12911-015-0155-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Donnell S. Use of administrative data for national surveillance of osteoporosis and related fractures in Canada: results from a feasibility study. Arch Osteoporos. 2013;8:143. doi: 10.1007/s11657-013-0143-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh J.A. Veterans affairs databases are accurate for gout-related health care utilization: a validation study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15(6):R224. doi: 10.1186/ar4425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wiebe N., Stenvinkel P., Tonelli M. Associations of chronic inflammation, insulin resistance, and severe obesity with mortality, myocardial infarction, cancer, and chronic pulmonary disease. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(8) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tonelli M., Wiebe N., Manns B.J., et al. Comparison of the complexity of patients seen by different medical subspecialists in a universal health care system. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(7) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.4852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alberta Health Services . Alberta Health Services; 2016. How to use the Pampalon deprivation index in Alberta: research and innovation. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Institut national de santé publique du Québec . 2021. Material and social deprivation index.https://www.inspq.qc.ca/en/deprivation/material-and-social-deprivation-index [Google Scholar]

- 25.Austin P.C., Daly P.A., Tu J.V. A multicenter study of the coding accuracy of hospital discharge administrative data for patients admitted to cardiac care units in Ontario. Am Heart J. 2002;144(2):290–296. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.123839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kokotailo R.A., Hill M.D. Coding of stroke and stroke risk factors using international classification of diseases, revisions 9 and 10. Stroke. 2005;36(8):1776–1781. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000174293.17959.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quan H., Li B., Saunders L.D., et al. Assessing validity of ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data in recording clinical conditions in a unique dually coded database. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(4):1424–1441. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00822.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ackroyd-Stolarz S., Bowles S.K., Giffin L. Validating administrative data for the detection of adverse events in older hospitalized patients. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2014;6:101–108. doi: 10.2147/DHPS.S64359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gruneir A., Cigsar C., Wang X., et al. Repeat emergency department visits by nursing home residents: a cohort study using health administrative data. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):157. doi: 10.1186/s12877-018-0854-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mansournia M.A., Altman D.G. Population attributable fraction. BMJ. 2018;360:k757. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Statistics Canada . 2022. Table 17-10-0005-01 Population estimates on July 1st, by age and sex.https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710000501 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Powell D.S., Oh E.S., Reed N.S., Lin F.R., Deal J.A. Hearing loss and cognition: what we know and where we need to go. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021;13 doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2021.769405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiam N.T., Li C., Agrawal Y. Hearing loss and falls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(11):2587–2596. doi: 10.1002/lary.25927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin F.R., Ferrucci L. Hearing loss and falls among older adults in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(4):369–371. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang J., Liu N., Zhao X. Assessing the relationship between hearing impairment and falls in older adults. Geriatr Nurs. 2022;47:145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2022.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Genther D.J., Betz J., Pratt S., et al. Association between hearing impairment and risk of hospitalization in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(6):1146–1152. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Genther D.J., Frick K.D., Chen D., Betz J., Lin F.R. Association of hearing loss with hospitalization and burden of disease in older adults. JAMA. 2013;309(22):2322–2324. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.5912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gates G.A., Cobb J.L., D'Agostino R.B., Wolf P.A. The relation of hearing in the elderly to the presence of cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular risk factors. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;119(2):156–161. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1993.01880140038006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Curti S.A., DeGruy J.A., Spankovich C., et al. Relationship of overall cardiovascular health and hearing loss in the Jackson heart study population. Laryngoscope. 2020;130(12):2879–2884. doi: 10.1002/lary.28469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williams N., Phillips N.A., Wittich W., et al. Hearing and cognitive impairments increase the risk of long-term care admissions. Innov Aging. 2020;4(2):igz053. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igz053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wells T.S., Wu L., Bhattarai G.R., Nickels L.D., Rush S.R., Yeh C.S. Self-reported hearing loss in older adults is associated with higher emergency department visits and medical costs. Inquiry. 2019;56 doi: 10.1177/0046958019896907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lubetzky A.V. Balance, falls, and hearing loss: is it time for a paradigm shift? JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;146(6):535–536. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.0415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thai A., Megwalu U.C. Association of self-reported hearing loss severity and healthcare utilization outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Otolaryngol. 2021;42(4) doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2021.102943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mikkola T.M., Polku H., Sainio P., Koponen P., Koskinen S., Viljanen A. Hearing loss and use of health services: a population-based cross-sectional study among Finnish older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):182. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0356-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blustein J. National Institutes of health funding for hearing loss research. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(7):687–689. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.0649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.National Institutes of Health (NIH) 2016. HHS FY 2017 budget in brief–NIH.https://www.hhs.gov/about/budget/fy2017/budget-in-brief/nih/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reed N.S., Altan A., Deal J.A., et al. Trends in health care costs and utilization associated with untreated hearing loss over 10 years. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(1):27–34. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2018.2875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tonelli M., Warick R. Focusing on the needs of people with hearing loss during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. JAMA. 2022;327(12):1129–1130. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.