Summary

Background

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a progressive interstitial lung disease with poor prognosis and a high economic burden for individuals and healthcare resources. Studies of the costs associated with the efficiency of IPF medications are scarce. We aimed to conduct a network meta-analysis (NMA) and cost-effectiveness analysis to identify the optimum pharmacological strategy among all currently available IPF regimens.

Methods

We first performed a systematic review and network meta-analysis. We searched eight databases for eligible randomised controlled trials (RCTs) published, in any language, between January 1, 1992 and July 31, 2022, that investigated the efficacy or tolerability (or both) of drug therapies for the treatment of IPF. The search was updated on February 1, 2023. Eligible RCTs were enrolled, with no restriction on dose, duration, or length of follow-up, if they included at least one of: all-cause mortality, acute exacerbation rate, disease progression rate, serious adverse events, and any adverse events under investigation. A subsequent Bayesian NMA within random-effects models was performed, followed by a cost-effectiveness analysis using the data obtained from our NMA, by developing a Markov model from the US payer's perspective. Assumptions were checked by deterministic and probabilistic sensitivity approaches to identify sensitive factors. We prospectively registered the protocol (CRD42022340590) in PROSPERO.

Findings

51 publications comprising 12,551 participants with IPF were analysed for the NMA, and the findings indicated that pirfenidone and N-acetylcysteine (NAC) + pirfenidone were the most efficacious and tolerable. The pharmacoeconomic analysis showed that NAC + pirfenidone was associated with the highest potentiality of being cost-effective at willingness-to-pay (WTP) thresholds of US$150,000 and $200,000, on the basis of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) and mortality, with the probability ranging from 53% to 92%. NAC was the minimum cost agent. Compared with placebo, NAC + pirfenidone improved effectiveness by increasing QALYs by 7.02, and reducing DALYs by 7.10 and deaths by 8.40, whilst raising overall costs by $516,894.

Interpretation

This NMA and cost-effectiveness analysis suggests that NAC + pirfenidone is the most cost-effective option for treatment of IPF at WTP thresholds of $150,000 and $200,000. However, given that clinical practice guidelines have not addressed the application of this therapy, large well-designed and multicentre trials are warranted to provide a better picture of IPF management.

Funding

None.

Keywords: Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, Drug strategy, Bayesian network meta-analysis, Cost-effectiveness analysis, All-cause mortality, Acute exacerbation

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a progressive interstitial lung disease with poor prognosis, eventuating high economic burden for individuals and healthcare resources. However, studies in regards to the costs associated with efficiency of IPF medications are scarce, mostly focused on few specific drugs with limited trials and participants. Literature search for network meta-analysis (NMA) was performed on Medline, Embase, Web of Science, CENTRAL, CNKI, ClinicalTrials.gov, WHO ICTRP, and ISRCTN Registry, of randomised controlled trials published between January 1, 1992, and July 31, 2022 (updated search: February 1, 2023), that investigated the efficacy or tolerability of drug therapies for treatment of IPF. Broad search terms related to combinations of eligible drug interventions and IPF. Previous NMA have generally compared drug treatments for IPF, which overlooked the parameters of health utility for further economic evaluation.

Added value of this study

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first evaluation of all currently available drug strategies for treatment of IPF that has offered a rank order for options on the balance of efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness. Through comprehensive retrieval, 51 studies comprising 12,551 individuals with IPF were identified for NMA, and exhibited a moderate risk of bias. This work updated the existing evidence of NMA assessing 20 regimens for IPF and focused on health utility values. The cost-effectiveness analysis brought together evidence on clinical effectiveness and costs. The combination of N-acetylcysteine (NAC) and pirfenidone had the highest potentiality of cost-effectiveness at willingness-to-pay thresholds of US$150,000 and $200,000, on the basis of quality-adjusted life year (QALY), disability-adjusted life year (DALY), and mortality outcomes.

Implications of all the available evidence

Current evidence suggests that NAC plus pirfenidone could be considered as a cost-effective option for treatment of IPF; however, clinical practice guidelines have not addressed the application of this therapy so further work is needed, which may provide support for the development of prescribing guidelines for rational drug use. Large well-designed and multicentre trials, addressing adverse events rate and quality of life under multifarious conditions, are warranted to provide a better picture of IPF management in future studies.

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a progressive, fibrosing and ultimately fatal interstitial lung disease (ILD) of unknown aetiology, primarily occurring in older adults.1,2 It is a rare disease, still the prevalence appears to have increased over the decades.3, 4, 5 Patients undergoing IPF carry a poor prognosis, with an estimated median survival within 3–5 years upon diagnosis without treatment,6,7 and characterised by declined pulmonary function, worsening dyspnea, and impaired health-related quality of life,8, 9, 10 eventuating a high global health burden of disease.5

Few pharmacological therapies are currently available for treatment of IPF, such as antifibrotic medications pirfenidone and nintedanib, which are approved to slow the rate of decline in forced vital capacity (FVC), however the progression of disease is neither halted nor reversed.11 Besides, recent trials on several investigational drugs and combinations indicate encouraging results to some extent, nevertheless, the benefits stay inconclusive.12,13 As a chronic respiratory condition, IPF requires lifelong medication. Moreover, the costs on drug therapies for IPF are uneven, and some couple with high prices.14 Due to the irreversible nature of IPF, as well as the multitude of acute exacerbation and hospitalisation that accompany it, a substantial economic burden has been imposed on individuals and overall healthcare resources.15, 16, 17

To date, studies in regards to the costs associated with efficiency of IPF medications are scarce, and mostly focus on few specific drugs with limited trials and participants.18,19 Thus, an unmet need exists for systematic evaluation on which treatment approach is more efficacious, well-tolerated and cost-effective in patients with IPF. We integrated direct and indirect evidence and conducted a network meta-analysis (NMA) with cost-effectiveness analysis, for the first time, upon randomised controlled trials (RCTs) so as to comprehensively summarise, compare and rank the relative potentiality for treatment of IPF among all currently available drug strategies from the US payer's perspective. These health-economic information may facilitate improved access to IPF medications who may most benefit for patients and clinicians, and inform drug pricing negotiation for policymakers.

Methods

Ethics

Relevant data were retrieved from public databases, including Medline, Embase, Web of Science, CENTRAL, CNKI, ClinicalTrials.gov, WHO ICTRP, and ISRCTN Registry. Ethical approval and informed consent were covered in the original studies and was not applicable for this study.

Network meta-analysis

This systematic review and network meta-analysis complied with the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) and the PRISMA extension statement for NMA.20, 21, 22 The protocol was prospectively registered with PROSPERO (registration number CRD42022340590).

Search strategy

To identify eligible RCTs, we performed literature searches on Medline, Embase, Web of Science Core Collection, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI, academic journal database), ClinicalTrials.gov, World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP), and International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) Registry published from 1 January 1992 to 31 July 2022 (date of last search: 1 February 2023), that investigated the efficacy and/or tolerability of drug therapies for treatment of IPF. Search terms and MeSH headings related to combinations of eligible drug interventions and IPF. Details for search strategy on the retrieved databases and registers were presented in Supplementary Text S1. Citations of a recently released systematic review and NMA,23 retrieved up to April 2021, was also scanned for additional inclusion. Reference lists of eligible trials and clinical guidelines were manually screened for potential enrolment.

Selection criteria

We considered eligible trials that met the following criteria: RCTs irrespective of design, in which an identified drug treatment or combinations of interventions were compared with placebo or no treatment. Patients were individuals diagnosed with IPF, defined by individual authors in accordance with 2022 update to the American Thoracic Society (ATS)/European Respiratory Society (ERS)/Japanese Respiratory Society (JRS)/Latin American Thoracic Association (ALAT) guidelines, without restrictions on sex, age and ethnicity. Interventions were drug therapies for treatment of IPF, with no restrict on dose, duration and length of follow-up. At least one of the following patient-important outcome was adopted: all-cause mortality, acute exacerbation rate, disease progression rate, serious adverse events, and any adverse events under investigation. No language restriction was imposed. Publication date was implemented in recent three decades given the changes in differential diagnosis process.24 Studies were excluded based on these criteria: duplicated data; ineligible study design; laboratory model; prophylactic effect studies; ineligible interventions and outcomes; inappropriate comparator and lack of sufficient data. Interventions and outcome parameters of interests were presented in Supplementary Text S2.

Data abstraction, risk of bias, and certainty of evidence

Teams of two reviewers (ZCY, YY, ZCR and LZH) independently screened papers by titles and abstracts for possible inclusion. If either reviewer considered a study potentially eligible, full text were retrieved and assessed criteria in duplicate for final inclusion. After pilot testing our standardised form, two authors (ZCY and JTL) independently extracted and summarised relevant information from main reports and supplementary materials of the enrolled trials, including study characteristics (e.g. first author, year of publication, region, study design and setting, sample size), participant characteristics (e.g. sex ratio, mean age, ethnicity), and treatment characteristics (e.g. intervention and dose, comparator and dose, duration, follow up, outcome parameters reported), etc. For multi-arm trials comparing dosage differences of an identical regimen, data were only extracted from a common or recommended dosage. If necessary, we approximated statistics from graphs. When possible, results based on the intention-to-treat principle were preferentially extracted. For trials identified from previous meta-analyses, extracted data were checked with the reported data to ensure accuracy (CJY). Corresponding authors of the original records were contacted to supplement incomplete or unpublished data.

Risk of bias of randomised trials was appraised in seven specified domains by two independent investigators (ZM and ZCR) with the Cochrane Collaboration’ tool.25 Each domain was scored as high risk, some concerns or low risk. Certainty of evidence for direct and network estimates was further investigated following GRADE framework (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) by two independent reviewers (ZCR and LZH), which classified quality of evidence as high, moderate, low, or very low certainty for each comparison and outcome.26 The starting point for RCT is high, and could be downward rated based on limitations in risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency (heterogeneity), indirectness, and publication bias.

Discrepancies among authors were settled by panel discussion to achieve a consensus during retrieval, data abstraction and risk of bias assessment process, when necessary, through arbitration by a senior scholar (CJY).

Data analysis

Data for pooling were calculated as rate ratio (RR) for dichotomous outcomes (that is, all-cause mortality, acute exacerbation, disease progression, serious adverse events and any adverse events); mean difference (MD) for continuous outcomes (that is, lung functions and health-related quality of life); and hazard ratio (HR) for survival analysis indexes, with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) as summary statistics, and were converted to the same unit of measurement, if required.27,28 The NMA combined no treatment and placebo into a single control node.

For available direct associations across interventions and outcomes, conventional pairwise random-effects model was imposed. Cochran’ Q test and I2 statistic were applied to assess the heterogeneity in treatment effects among trials.29,30 T-statistic (Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method) was used for small sample analysis (n < 10).31 Heterogeneity variance was estimated based on restricted maximun likelihood (REML) approach in both direct and indirect comparisons.32 To explore the efficacy and tolerability of each intervention for IPF, we estimated absolute rates as well. A two sided P value less than 0.05 indicated as statistical difference, barring the Q test, where P value of 0.10 was set.33,34 Sensitivity analyses were planned on clinical trial phase and risk of bias.

We undertook a bayesian NMA to simultaneously compare all relevant drug therapies for each parameter, and pooled data were synthesised within random effects models. We appraised the ranking probabilities of drug therapies for treatment of IPF, and offered a relative hierarchy grounded on surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA).35 Cluster plots of SUCRA values were constructed for pairs of efficacy and safety outcomes to assess benefit and risk concurrently. Publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of comparison adjusted funnel plots asymmetry,36 and Begg's and Egger's tests, where appropriate.37 Trim-and-fill analysis was further performed to account for possible publication bias.38

Key characteristics within treatment comparisons were compared to appraise whether effect modifiers were similarly distributed across trials, to seek for potential sources of clinical and methodological heterogeneity. Node-spitting approach and Higgins model (design-by-treatment interaction model) were adopted for evaluating network consistency assumption for primary endpoints.39,40 The design-by-treatment interaction model provided a global assumption of consistency across the entire network. The node splitting method separated evidence into direct and indirect on a particular comparison (node) and then assessed their discrepancies.

Data synthesis was conducted using STATA (version 17.0, TX, USA), WinBUGS (version 1.4.3, Cambridge, UK), Review manager software (RevMan, version 5.4, Copenhagen, Danmark) and GRADEprofiler (version 3.6, Hamilton, Canada).

Pharmacoeconomic analysis

In cost-effectiveness analysis, we evaluated all currently available drug strategies for treatment of IPF using the data obtained from our NMA. Only recommended doses were considered. Pentraxin, pamrevlumab and simtuzumab were excluded from this analysis because of insufficiently evidence regarding drug price. The combination of nintedanib and pirfenidone was excluded for inadequate information on acute exacerbation. Considering that US dollar had certain advantages on data generalisability, we developed the economic model from the US payer's perspective.41 This research followed the CHEERS (Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards) reporting guideline.42

Model structure

A Markov model was developed and simulated to estimate the cost-effectiveness, in which placebo was included simultaneously with all treatment options. Each regimen has the same model structure yet with different costs, effectiveness, and event probabilities. The model was established in yearly cycles using TreeAge Pro Software (version 2020, Williamstown, Massachusetts, USA) with the following four mutually independent health states: IPF, disease progression, acute exacerbation and death. The initial model states for all participants were IPF, and transitioned to acute exacerbation, progressed disease, death or stayed in IPF state. Simulations were run over 10,000 iterations, with each iteration representing one patient. At each time point, the proportion of participants in certain Markov state was decided by our NMA estimates. Time horizon was set at 11 years, and the range was estimated from the baseline age (67 years) acquired from NMA to the life expectancy (78 years) reported by US life-tables.43

Effectiveness

We measured quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) and all-cause mortality among regimens. Mean value was adopted as the value of its state with beta distributions. For estimating QALYs, data were collected from the enrolled RCTs in our NMA, which reported utility scores of quality of life in different health states related to the economic model, comprising EuroQol Five Dimensions Questionnaire (EQ-5D) and St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) index. EQ-5D was preferentially abstracted, when reported. Conversion equation was obtained as described in the study by Starkie et al. (EQ-5D utility = 0.9617–0.0013 SGRQ Total-0.0001 SGRQ Total 2 + 0.0231 Male).44 Global DALYs were sourced from Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study 2017.45 Death was the terminal state of Markov model, and the number of death cases in each cycle was calculated by the model parameters. We merged the rates of all-cause mortality, acute exacerbation and disease progression, which were extracted from NMA by meta-analysis method, calculated the 95% CI and standard deviation, and inputted in to the pharmacoeconomic model.46

Costs inputs

The direct medical cost parameters were estimated, including drug acquisition, inspection, pulmonary function test, CT chest, oxygen therapy and acute exacerbation cost. We calculated costs and effects per simulated patient with the same discount rate 5% (0–8%) per year, represented with gamma distribution.47, 48, 49 The general disease status involved examination and testing costs related to follow-up care. With disease progressed, patients received additional oxygen support therapy. We uniformly summarised the use of equipments and drugs during first aid and hospitalisation (oxygen treatment included), as an episode expense of acute exacerbation. Drug costs were derived from the 2022 average sales price (ASP) drug pricing files of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).50 We modeled the costs of therapy administration, pulmonary function test, CT chest, and oxygen therapy based on the 2023 Medicare physician fee schedule.51 A paper published by Yu et al.52 rendered the management costs related to acute exacerbation. Inspection and pulmonary function test were set as three times per year; CT chest was set as one time per year; oxygen therapy was set as twice a week.1,53 We adopted baseline values as the mean, and plus or minus 25% from mean values as standard deviation for cost inputs. All costs were inflated to 2022 US dollars using the Consumer Price Index.

Cost-effectiveness analyses

To seek for the optimal treatment for IPF, we employed the method of extended dominance in the cost-effectiveness analysis.54 Cost-effectiveness was further assessed by calculating incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs), interpreted as the expected cost per additional unit gain in utility, using the willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold values of US$150,000 and $200,000 per utility.55,56 We measured the likelihood that an intervention being most cost-effective under a certain cost-effectiveness threshold. Net monetary benefit (NMB), defined as the monetary benefit of an agent in terms of health gained minus the costs, was also estimated for each treatment strategy.

Sensitivity analyses

To account for the uncertainty of model parameters on calculated estimates, assumptions were checked by deterministic and probabilistic sensitivity testing approaches to identify sensitive factors. One-way deterministic sensitivity analyses were conducted, exhibiting the robustness of expected ICERs to key parameters of the model, and summarised as tornado diagrams. Probabilistic sensitivity analyses were performed by drawing random samples out of their respective statistical distributions within 10,000 Monte Carlo simulations, to verify the global parameter robustness, and were depicted as cost-effectiveness scatter plots and cost-effectiveness acceptability curves.57 Table 1 summarised key parameter inputs to the economic model, including cost data and health utility estimates, evidence sources, ranges of the sensitivity analyses, and provided details on the types of distributions assigned to each.

Table 1.

Key parameter inputs to the economic model and the ranges of the sensitivity analyses.

| Baseline value | Lower limit | Upper limit | Distributiona | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug cost (per year), $b | |||||

| NAC (600 mg, tid) | 11,232 | 8,424c | 14,040c | Gamma (11,232, 2808) | CMS 202250 |

| Ambrisentan (10 mg, qd) | 110,783 | 83,087c | 138,479c | Gamma (110,783, 27,696) | CMS 202250 |

| Bosentan (125 mg, bid) | 250,200 | 187,650c | 312,750c | Gamma (250,200, 62,550) | CMS 202250 |

| Imatinib (600 mg, qd) | 570,910 | 428,182c | 713,637c | Gamma (570,910, 142,727) | CMS 202250 |

| Macitentan (10 mg, qd) | 103,820 | 77,865c | 129,776c | Gamma (103,820, 25,956) | CMS 202250 |

| Nintedanib (150 mg, bid) | 106,632 | 79,974c | 133,290c | Gamma (106,632, 26,658) | CMS 202250 |

| Pirfenidone (400 mg, tid) | 23,198 | 17,399c | 28,998c | Gamma (23,198, 5800) | CMS 202250 |

| Sildenafil (20 mg, tid) | 46,148 | 34,611c | 57,686c | Gamma (46,148, 11,538) | CMS 202250 |

| Colchicine (1 mg, qd) | 1858 | 1,393c | 2,322c | Gamma (1,858, 464) | CMS 202250 |

| Cyclophosphamide (100 mg, qd) | 44,856 | 33,642c | 56,070c | Gamma (44,856, 11,214) | CMS 202250 |

| Etanercept (2.5 mg, biw) | 767,902 | 575,926c | 959,877c | Gamma (767,902, 191,975) | CMS 202250 |

| IFN-γ (200ug, tid) | 98,606 | 73,954c | 123,257c | Gamma (98,606, 24,651) | CMS 202250 |

| Warfarin (2.5 mg, qd) | 774 | 581c | 968c | Gamma (774, 194) | CMS 202250 |

| Follow-up cost (per year), $b | |||||

| Acute exacerbation | 14,731 | 11,048c | 18,414c | Gamma (14,731, 3683) | Yu 201652 |

| Oxygen therapyd | 6978 | 5,234c | 8,723c | Gamma (6,978, 1745) | Medicare PFS51 (CPT4: 94,453) |

| Pulmonary function testd | 132 | 99c | 165c | Gamma (132, 33) | Medicare PFS51 (CPT4: 94,727) |

| CT chestd | 140 | 105c | 175c | Gamma (140, 35) | Medicare PFS51 (CPT4: 771,250) |

| Inspectiond | 107 | 81c | 134c | Gamma (107, 27) | Medicare PFS51 (CPT4: G0463) |

| Health utilitiese | |||||

| Progression-free survival (QALYs) | 0.88 | 0.75f | 0.93f | Beta (0.88, 0.09) | Mohindru 2020,58 King 2008,59 Behr 2019,60 Richeldi 201413 |

| Progressed disease (QALYs) | 0.82 | 0.74f | 0.87f | Beta (0.82, 0.06) | Mohindru 202058 |

| Acute exacerbation (QALYs) | 0.60 | 0.44f | 0.76f | Beta (0.60, 0.16) | Mohindru 202058 |

| Progression-free survival (DALYs) | 0.02 | 0.01f | 0.03f | Beta (0.02, 0.01) | GBD 201745 |

| Progressed disease (DALYs) | 0.22 | 0.15f | 0.31f | Beta (0.22, 0.08) | GBD 201745 |

| Acute exacerbation (DALYs) | 0.41 | 0.27f | 0.56f | Beta (0.41, 0.14) | GBD 201745 |

| Effectivenessg | |||||

| All-cause mortality | |||||

| Acute exacerbation | 0.62 | 0.49f | 0.83f | Beta (0.62, 0.17) | Arai 2017,61 Aso 2019,62 Hozumi 2019,63 Kawamura 201764 |

| NAC | 0.02 | 0.01f | 0.13f | Beta (0.02, 0.01) | NMA Fig. 2B |

| Ambrisentan | 0.08 | 0.07f | 0.09f | Beta (0.08, 0.02) | NMA Fig. 2B |

| Bosentan | 0.04 | 0.03f | 0.04f | Beta (0.04, 0.03) | NMA Fig. 2B |

| Imatinib | 0.04 | 0.02f | 0.11f | Beta (0.04, 0.01) | NMA Fig. 2B |

| Macitentan | 0.29 | 0.24f | 0.32f | Beta (0.29, 0.04) | NMA Fig. 2B |

| Nintedanib | 0.13 | 0.07f | 0.29f | Beta (0.05, 0.01) | NMA Fig. 2B |

| Pirfenidone | 0.13 | 0.03f | 0.41f | Beta (0.07, 0.01) | NMA Fig. 2B |

| Sildenafil | 0.08 | 0.04f | 0.11f | Beta (0.14, 0.02) | NMA Fig. 2B |

| placebo or no treatment | 0.18 | 0.01f | 0.81f | Beta (0.16, 0.01) | NMA Fig. 2B |

| NAC + Pirfenidone | 0.04 | 0.02f | 0.06f | Beta (0.04, 0.01) | NMA Fig. 2B |

| Nintedanib + sildenafil | 0.10 | 0.09f | 0.11f | Beta (0.10, 0.02) | NMA Fig. 2B |

| Colchicine | 0.41 | 0.39f | 0.43f | Beta (0.41, 0.09) | NMA Fig. 2B |

| Cyclophosphamide | 0.47 | 0.40f | 0.54f | Beta (0.48, 0.04) | NMA Fig. 2B |

| Etanercept | 0.02 | 0.01f | 0.03f | Beta (0.02, 0.02) | NMA Fig. 2B |

| IFN-γ | 0.16 | 0.15f | 0.17f | Beta (0.17, 0.02) | NMA Fig. 2B |

| Warfarin | 0.19 | 0.16f | 0.22f | Beta (0.19, 0.09) | NMA Fig. 2B |

| Pirfenidone + sildenafil | 0.17 | 0.14f | 0.20f | Beta (0.17, 0.04) | NMA Fig. 2B |

| Acute exacerbation rate | |||||

| NAC | 0.04 | 0.01f | 0.28f | Beta (0.04, 0.01) | NMA Fig. 2D |

| Ambrisentan | 0.13 | 0.11f | 0.15f | Beta (0.13, 0.02) | NMA Fig. 2D |

| Bosentan | 0.11 | 0.03f | 0.14f | Beta (0.11, 0.01) | NMA Fig. 2D |

| Imatinib | 0.09 | 0.03f | 0.14f | Beta (0.09, 0.01) | NMA Fig. 2D |

| Macitentan | 0.06 | 0.05f | 0.07f | Beta (0.06, 0.02) | NMA Fig. 2D |

| Nintedanib | 0.05 | 0.04f | 0.12f | Beta (0.05, 0.01) | NMA Fig. 2D |

| Pirfenidone | 0.11 | 0.02f | 0.42f | Beta (0.11, 0.01) | NMA Fig. 2D |

| Sildenafil | 0.06 | 0.03f | 0.31f | Beta (0.06, 0.02) | NMA Fig. 2D |

| placebo or no treatment | 0.08 | 0.02f | 0.68f | Beta (0.08, 0.01) | NMA Fig. 2D |

| NAC + Pirfenidone | 0.03 | 0.01f | 0.03f | Beta (0.03, 0.02) | NMA Fig. 2D |

| Nintedanib + sildenafil | 0.09 | 0.07f | 0.21f | Beta (0.09, 0.02) | NMA Fig. 2D |

| Colchicine | 0.25 | 0.08f | 0.14f | Beta (0.25, 0.01) | NMA Fig. 2D |

| Cyclophosphamide | 0.25 | 0.19f | 0.31f | Beta (0.25, 0.01) | NMA Fig. 2D |

| Etanercept | 0.63 | 0.51f | 0.75f | Beta (0.63, 0.07) | NMA Fig. 2D |

| IFN-γ | 0.05 | 0.05f | 0.25f | Beta (0.05, 0.01) | NMA Fig. 2D |

| Warfarin | 0.29 | 0.23f | 0.35f | Beta (0.29, 0.01) | NMA Fig. 2D |

| Pirfenidone + sildenafil | 0.11 | 0.08f | 0.14f | Beta (0.11, 0.03) | NMA Fig. 2D |

| Disease progression rate | |||||

| NAC | 0.11 | 0.02f | 0.36f | Beta (0.11, 0.01) | NMA Fig. 2F |

| Ambrisentan | 0.27 | 0.22f | 0.31f | Beta (0.27, 0.02) | NMA Fig. 2F |

| Bosentan | 0.26 | 0.16f | 0.31f | Beta (0.26, 0.02) | NMA Fig. 2F |

| Imatinib | 0.25 | 0.21f | 0.29f | Beta (0.25, 0.05) | NMA Fig. 2F |

| Macitentan | 0.21 | 0.18f | 0.25f | Beta (0.21, 0.04) | NMA Fig. 2F |

| Nintedanib | 0.49 | 0.29f | 0.71f | Beta (0.49, 0.01) | NMA Fig. 2F |

| Pirfenidone | 0.15 | 0.02f | 0.44f | Beta (0.15, 0.05) | NMA Fig. 2F |

| Sildenafil | 0.07 | 0.03f | 0.53f | Beta (0.07, 0.02) | NMA Fig. 2F |

| Placebo or no treatment | 0.29 | 0.04f | 0.72f | Beta (0.29, 0.01) | NMA Fig. 2F |

| NAC + Pirfenidone | 0.25 | 0.13f | 0.65f | Beta (0.25, 0.04) | NMA Fig. 2F |

| Nintedanib + sildenafil | 0.26 | 0.21f | 0.31f | Beta (0.26, 0.04) | NMA Fig. 2F |

| Colchicine | 0.56 | 0.30f | 0.79f | Beta (0.56, 0.11) | NMA Fig. 2F |

| Cyclophosphamide | 0.20 | 0.15f | 0.25f | Beta (0.20, 0.05) | NMA Fig. 2F |

| Etanercept | 0.07 | 0.04f | 0.08f | Beta (0.07, 0.04) | NMA Fig. 2F |

| IFN-γ | 0.09 | 0.08f | 0.25f | Beta (0.09, 0.01) | NMA Fig. 2F |

| Warfarin | 0.25 | 0.21f | 0.29f | Beta (0.25, 0.05) | NMA Fig. 2F |

| Pirfenidone + sildenafil | 0.73 | 0.66f | 0.80f | Beta (0.73, 0.05) | NMA Fig. 2F |

| Other | |||||

| Age, years | 67.30 | 66.54h | 68.04h | Normal (67.30, 0.75) | Supplemental Table S1 |

| Discount rate, % | 0.05 | 0.00f | 0.08f | Normal (0.05, 0.04) | Sanders 2016,47 Hultkrantz 202148 |

| Follow-up period, years | 12.00 | 11.00h | 17.00h | Normal (12.00, 3.21) | Supplemental Table S1 |

| Expected life, years | 78.5 | NA | NA | Uniform (78.5) | WHO 202243 |

Abbreviations: NA, Not applicable; IFN-γ, Interferon-γ; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; qd, Once daily; bid, Twice a day; tid, Three times a day; biw, twice a week; NMA, Network meta-analysis; CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; PFS, Physician fee schedule; GBD, Global Burden of Disease; WHO, World Health Organization; QALY, Quality-adjusted life year; DALY, Disability-adjusted life year.

Distributions were presented as (mean, standard deviation).

All costs estimates were inflated to 2022 US dollars using the Consumer Price Index.

Baseline values as the mean; plus or minus 25% from mean values were adopted to estimate standard deviation.

Inspection and pulmonary function test were set as three times per year; CT chest was set as one time per year; oxygen therapy was set as twice a week.

The health utilities are values that vary between 0 and 1, and have no units.

Possible maximum and minimum values.

The transition probability and absolute risk for all-cause mortality, acute exacerbation and disease progression per year, were derived from our network meta-analysis, as shown in Fig. 2B, D and F.

Values with 95% confidence intervals.

Role of the funding source

The authors received no funding for this study.

Results

Network meta-analysis

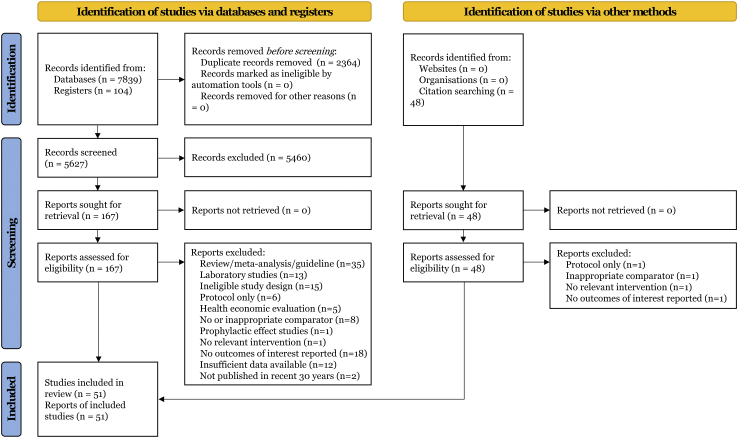

Fig. 1 presented the literature search process. From 7839 potentially relevant records, we identified 51 eligible articles (53 trials, 12,551 participants involved, listed in Supplementary Text S3) in accord with the eligibility criteria, which covered 20 unique drug therapies for treatment of IPF. A summary list of studies excluded at full-text screening stage was shown in Supplementary Text S4. In total, 6872 participants were randomly assigned to an active intervention and 5679 to controls. Descriptions of the retrieved publications were available in Supplementary Table S1. Baseline characteristics including sex, age, sample size, dosage, duration, follow-up, and comparator arms were generally balanced across studies. The medians and interquartile ranges for male ratio, age, and sample size of each comparison arm were 0.76 (0.08), 67.49 (3.69), and 119 (188), respectively. With respect to ethnicity, 38 (76.5%) of the studies provided White patients, 16 (31.4%) provided Asian patients.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart ofsearch strategy.

Supplementary Fig. S1 exhibited the overall results of risk of bias assessment for each research, that identified the main limitations as possible lack of performance bias (7/51, 13.7%) and detection bias (10/51, 19.6%) listed in Supplementary Table S2.

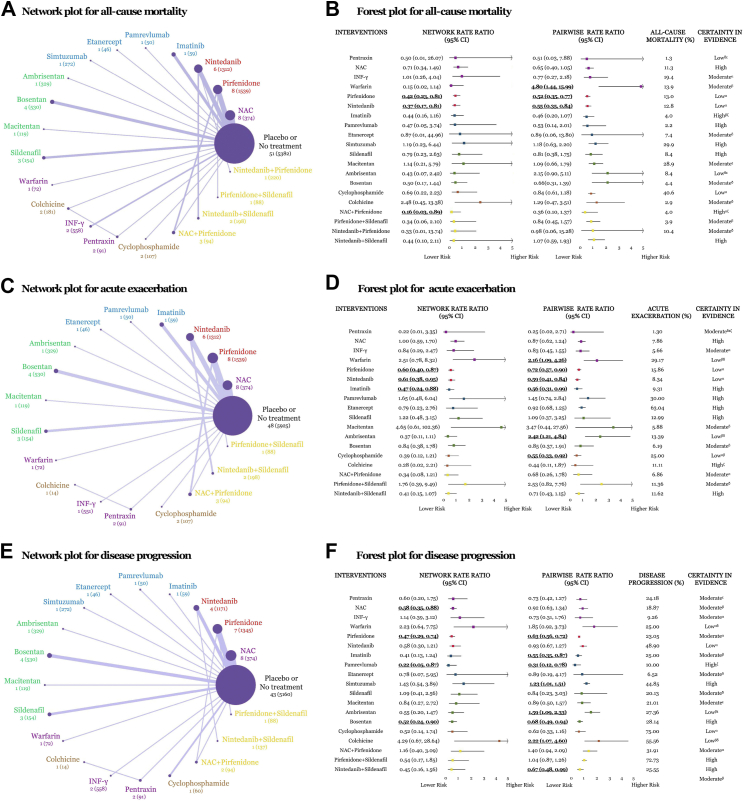

In terms of alleviating all-cause mortality, the efficacy of drug therapies for IPF was assessed for all 20 interventions, and a network of eligible comparisons was presented in Fig. 2A. NMA estimated from 53 trials with a total of 12,551 participants. Of 210 possible comparisons, 26 (12.4%) were compared in publications directly. Pirfenidone (RR [95% CI], 0.42 [0.23, 0.81]), nintedanib (0.37 [0.17, 0.81]) and N-acetylcysteine (NAC) + pirfenidone (0.16 [0.03, 0.89]), were associated with decreased all-cause mortality with statistically superiority compared with placebo or no treatment in NMA (Fig. 2B). Absolute rates ranged from 1.3% to 47.9% for all options presented respectively in Fig. 2B. Ranking on reducing all-cause mortality, pentraxin appeared to be the highest one, followed by nintedanib + pirfenidone, NAC + pirfenidone, etanercept, nintedanib, pirfenidone et al., however, data derived from pentraxin, nintedanib + pirfenidone or etanercept was provided by merely one case. GRADE summary for each comparison on all-cause mortality was summarised in Fig. 2B, and moderate certainty of evidence was noticed. Most pairwise meta-analyses (PWA) indicated outstanding consistency in both tendency and significance with respect to the corresponding NMA results, apart from interferon-γ (IFN-γ), warfarin, ambrisentan, and nintedanib + sildenafil in tendency, warfarin and NAC + pirfenidone in significance. Supplementary Fig. S2 represented all regimens suggesting the individual contributions to the holistic outcomes of all-cause mortality. Substantial between-study heterogeneity was noted in cyclophosphamide, IFN-γ, nintedanib and pirfenidone for all-cause mortality (I2 = 50.6%, 75.7%, 62.1%, 68.0%, respectively, Supplementary Table S3).

Fig. 2.

Network geometries and forest plots of drug therapies for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis on treatment efficacy. (A) Network geometry of eligible comparisons for all-cause mortality. Line width corresponds to the proportional to the number of individual trials it connects comparing each pair of interventions. Node size corresponds to the proportional to the number of randomly assigned participants contributing to particular treatment. Number of the trials (patients) were exhibited. (B) Summary plot for all-cause mortality. Pooled risk estimates represented summary rate ratio with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) compared with placebo or no treatment. Bold and underlined indicated statistically significance. (C) Network geometry for acute exacerbation. (D) Summary plot for acute exacerbation. (E) Network geometry for disease progression. (F) Summary plot for disease progression. Abbreviations: NAC, N-acetylcysteine; IFN-γ, Interferon-γ. αLimitations in study design or execution (risk of bias); βInconsistency in results; γIndirectness of evidence; δImprecision of results; εPublication bias; ζMagnitude of the effect; ηPlausible confounding.

With regard to acute exacerbation, 18 interventions (46 trials, 10,952 participants) were assessed, and network geometry was exhibited in Fig. 2C. Pirfenidone (0.60 [0.40, 0.87]), nintedanib (0.61 [0.38, 0.95]) and imatinib (0.47 [0.24, 0.88]), presented significant difference compared with placebo or no treatment in NMA (Fig. 2D). Pentraxin had the highest superiority to reduce the incidence of acute exacerbation when comparing and ranking these treatments, followed by nintedanib + sildenafil, NAC + pirfenidone, imatinib, nintedanib, pirfenidone et al., however, information on pentraxin was provided by only one study. GRADE summary indicated high to moderate certainty of evidence on acute exacerbation.

For progression of disease, 19 interventions (44 trials, 10,437 participants) were evaluated, and network geometry was showed in Fig. 2E. NAC (0.58 [0.35, 0.88]), pirfenidone (0.47 [0.29, 0.74]), pamrevlumab (0.22 [0.05, 0.87]) and bosentan (0.52 [0.24, 0.90]), revealed statistical significance compared with placebo or no treatment in NMA, based on moderate certainty (Fig. 2F). Ranking on alleviating disease progression, pamrevlumab seemed to be the first choice, followed by bosentan, pirfenidone, etanercept, pentraxin, NAC et al., however, data from pamrevlumab, etanercept or pentraxin was provided by merely one trial.

Supplementary Fig. S3 and S4 represented all regimens suggesting the individual contributions to the holistic outcomes of acute exacerbation and disease progression. Substantial between-study heterogeneity was noted in bosentan, pirfenidone in acute exacerbation (I2 = 53.8%, 55.1%), and IFN-γ, NAC, nintedanib, sildenafil in disease progression (I2 = 74.4%, 57.1%, 92.4%, 65.5%, respectively, Supplementary Table S3).

For lung function (Supplementary Fig. S5A–C), NAC (MD [95% CI], 0.08 [0.07, 0.09]) and nintedanib + sildenafi (1.40 [1.26, 1.54]) significantly reversed FVC decline; nintedanib + sildenafil (0.90 [0.73, 1.07]), NAC (0.10 [0.04.0.16]) and pirfenidone (0.13 [0.07, 0.20]) significantly reversed diffusion capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO) decline; NAC + pirfenidone (52.12 [43.71, 60.53]), simtuzumab (45.00 [41.19, 48.81]), pentraxin (24.50 [20.59, 28.41]), NAC (24.18 [21.85, 26.50]), pirfenidone (23.74 [3.99, 43.50]) and nintedanib (22.53 [4.85, 40.20]) significantly reversed 6-min walk test (6MWD) decline, compared with placebo or no treatment.

For survival analysis (Supplementary Fig. S6A and B), nintedanib (HR [95% CI], 0.61 [0.50, 0.73]), pirfenidone (0.56 [0.44, 0.67]) and bosentan (0.79 [0.59, 0.99]) significantly increased probability of survival; pirfenidone (0.63 [0.50, 0.75]), bosentan (0.79 [0.59, 0.99]), ambrisentan (0.57 [0.32, 0.82]) and nintedanib + sildenafi (0.68 [0.38, 0.99]) significantly raised probability of progression-free survival.

For health-related quality of life (Supplementary Fig. S7A–C), bosentan (MD [95% CI], −6.60 [−9.60, −3.60]) significantly decreased University of California, San Diego, Shortness of Breath Questionnaire (UCSD-SOBQ) score, and sildenafil (−4.08 [−7.30, −0.86]) significantly decreased SGRQ score.

In terms of serious adverse events, 19 interventions (45 trials, 10,174 participants) were assessed, and network geometry was exhibited in Supplementary Fig. S8A. Most drugs reported no obvious difference compared with placebo or no treatment in NMA and PMA, apart for ambrisentan (9.86 [3.80, 26.50]) in NMA (Supplementary Fig. S8B). With regard to any adverse events, 20 interventions (43 trials, 11,305 participants) were evaluated, and network geometry was showed in Supplementary Fig. S9A. Nintedanib was associated with elevated incidence of any adverse events with statistical significance compared with placebo or no treatment in both NMA (2.29 [1.20, 5.04]) and PWA (1.26 [1.07, 1.51]) listed in Supplementary Fig. S9B. Supplementary Figs. S10–S11 represented all regimens suggesting the individual contributions to the holistic outcomes of adverse reactions. Substantial between-study heterogeneity was noted in NAC, nintedanib, pirfenidone and sildenafil for any adverse event (I2 = 57.9%, 73.3%, 79.8%, 69.1%, respectively, Supplementary Table S3).

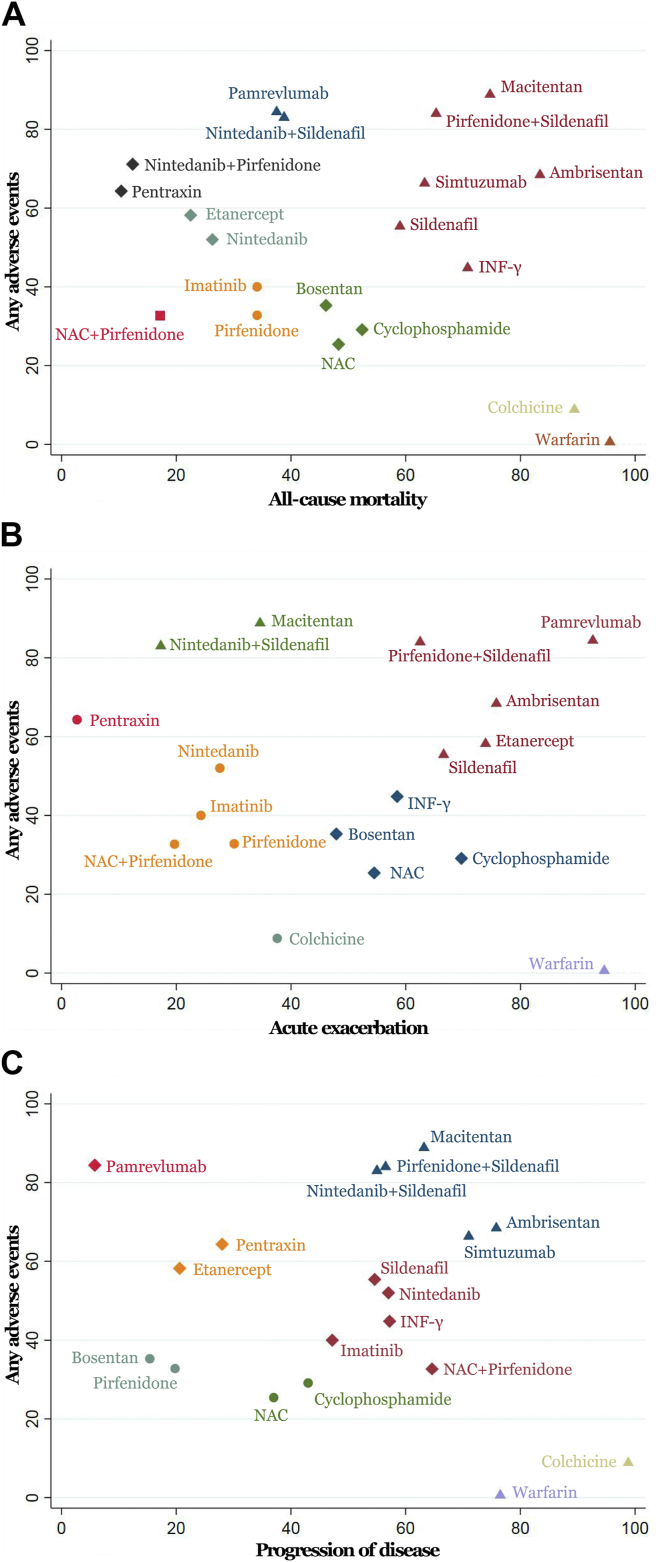

Each regimen was ranked according to both dimensions of benefits and harms summarised in Fig. 3. With regards to alleviating all-cause mortality, NAC + pirfenidone and pirfenidone were better in either efficacy or tolerability, as located in the lower left corner (Fig. 3A). In terms of reducing acute exacerbation, pirfenidone, imatinib and nintedanib showed better effectivenes and tolerance, as appeared in the lower left (Fig. 3B). For progression of disease, pirfenidone and bosentan implied better in efficacy and safety for IPF in lower left quarter (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Cluster ranking plots of surface under cumulative ranking curves for efficacy and tolerability results from network meta-analysis. (A) All-cause mortality versus serious adverse events. (B) Disease progression versus serious adverse events. (C) Acute exacerbation versus any adverse events.

No evidence for global inconsistency was reported depending on design-by-treatment interaction method. Node-splitting approach implied no major inconsistency between direct and indirect comparisons for all-cause mortality apart from warfarin and ambrisentan, vs. placebo or no treatment. No significant difference was observed in sensitivity analyses on clinical trials phases (all studies vs. without phase II or without phase II&III, Supplementary Table S4). As for sensitivity analysis on high risk of bias studies, statistical discrepancy was noticed in nintedanib for all-cause mortality and nintedanib, pirfenidone for acute exacerbation (all studies vs. studies without high risk of bias, Supplementary Table S4). Visual inspection of funnel plots (Supplementary Fig. S12A–E) and Begg's and Egger's tests (Supplementary Table S5) didn't reveal prominent asymmetry for main indicators, implying no substantial evidence of publication bias, expect for imatinib in all-cause mortality and any adverse event. Trim-and-fill analysis further indicated no significant changes on imatinib in publication bias (Supplementary Table S6).

Pharmacoeconomic analysis

Main assumptions and structure of the model were provided in Supplementary Fig. S13. Effectiveness inputs from NMA for the cost-effectiveness analysis were shown in Supplementary Fig. S14. The results of cost-effectiveness analysis on effective regimens were exhibited in Supplementary Fig. S15. NAC was the minimum cost agent. NAC and the combination of NAC and pirfenidone were recommended as the dominant strategy based on QALY, DALY or mortality, for lower cost and greater utility. Table 2 described the costs, effects and ICERs of all treatment options for IPF compared with placebo.

Table 2.

Costs, effects and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios of all treatment options for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis compared with placebo.

| Cost ($) | Quality-adjusted life year |

Disability-adjusted life year |

Mortality |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | ICER ($/QALY) | Effect | ICER ($/DALY) | Effect | ICER ($/Death) | ||

| Ambrisentan | 1,390,709 | 12.12 | 351,083 | 12.43 | 338,887 | 14.81 | 281,591 |

| Bosentan | 3,731,536 | 15.10 | 539,526 | 14.81 | 578,244 | 17.87 | 468,589 |

| Imatinib | 8,441,770 | 15.16 | 1,214,542 | 15.49 | 1,187,133 | 17.87 | 1,064,068 |

| NAC | 171,199 | 12.46 | 34,564 | 13.21 | 30,396 | 14.81 | 30,145 |

| NAC + pirfenidone | 541,889 | 15.25 | 73,632 | 15.50 | 72,802 | 18.36 | 61,535 |

| Nintedanib | 1,523,262 | 14.29 | 247,239 | 14.13 | 261,478 | 17.39 | 201,651 |

| Sildenafil + nintedanib | 1,645,400 | 10.48 | 720,180 | 10.73 | 695,453 | 12.69 | 593,555 |

| Pirfenidone | 339,890 | 12.97 | 66,434 | 13.58 | 60,791 | 15.61 | 55,734 |

| Sildenafil | 449,460 | 9.31 | 393,023 | 9.99 | 266,959 | 10.95 | 428,753 |

Abbreviations: NAC, N-acetylcysteine; ICER, Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; QALY, Quality-adjusted life year; DALY, Disability-adjusted life year.

As summarised in Supplementary Tables S7–S9, NAC yielded an additional 4.23 QALYs, 4.81 DALYs or 4.85 death compared with placebo, with a minimum cost of $171,199. NAC + pirfenidone improved effectiveness by prolonging 7.02 QALYs and reducing 7.10 DALYs and 8.40 death, and raised an overall cost by $516,894, resulting in ICERs of $73,632 per QALY, $72,802 per DALY and $61,535 per death, respectively. Expected incremental net money benefits at $100,000, $150,000 and $200,000 WTP thresholds were shown in Supplementary Tables S7–S9. Given WTP thresholds of $150,000 and $200,000 per utility, NAC + pirfenidone had the highest probability being cost-effective for patients undergoing IPF, reported as 60%–79% for QALY, 53%–72% for DALY and 83%–92% for mortality.

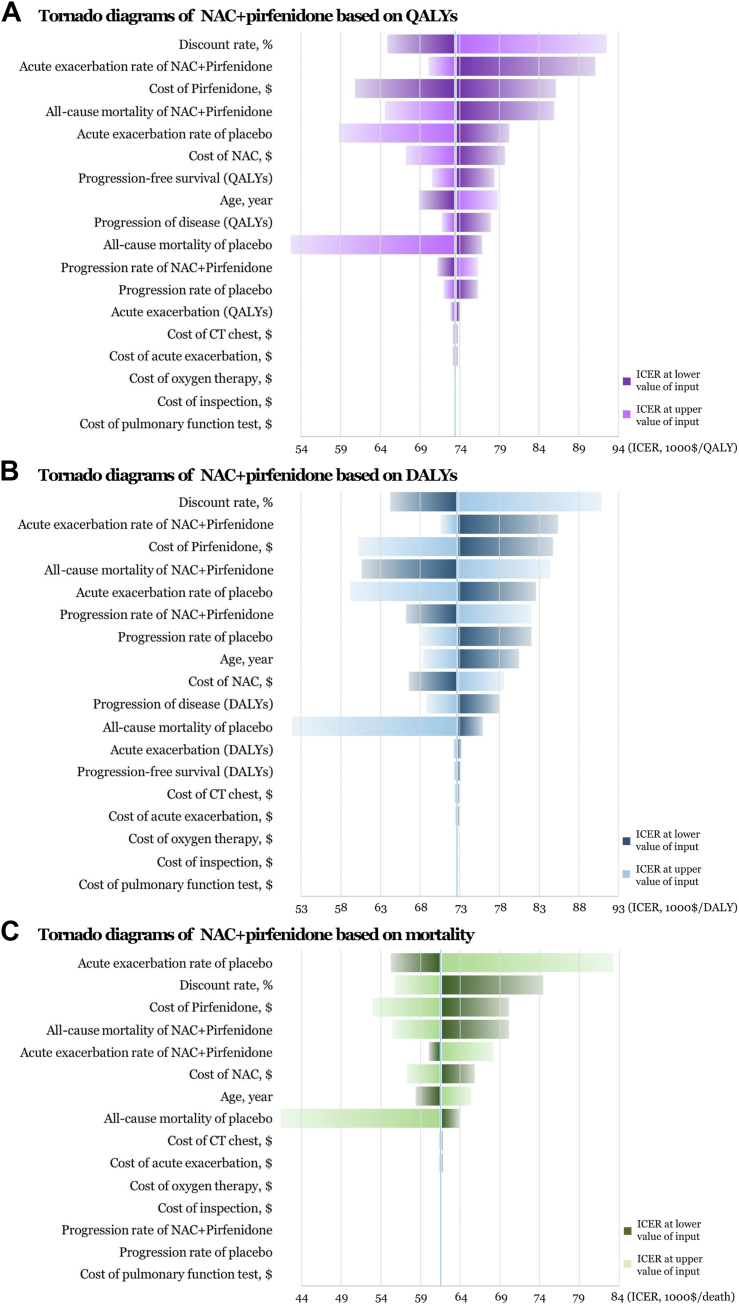

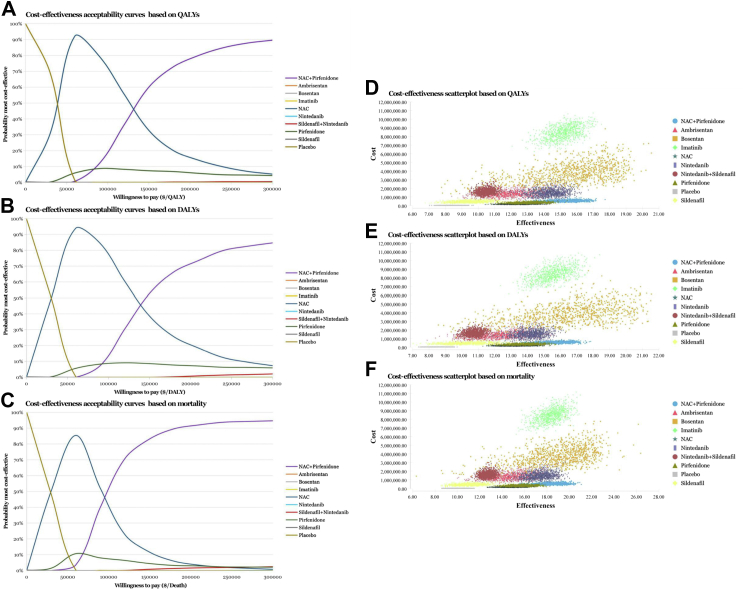

We performed several sensitivity analyses to test the stability of the model under various assumptions. Univariate deterministic sensitivity analysis of the cost-effective agents described the changes of base case values to their lower and upper values, with 23 parameters involved. Tornado diagrams of NAC + pirfenidone were provided in Fig. 4, implying that there was no susceptible factor noted within the WTP thresholds of $150,000 and $200,000. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves of probabilistic sensitivity analyses on all treatment options were exhibited in Fig. 5A–C. NAC had the highest probability being cost-effective at WTP thresholds between $40,000 and $90,000 approximately, as the threshold increased, NAC + pirfenidone had the highest probability being cost-effective when assuming WTP between $140,000 and $300,000 approximately, based on QALY, DALY and mortality. Cost-effectiveness scatter plots of all available IPF regimens were listed in Fig. 5D–F.

Fig. 4.

Tornado diagrams of deterministic sensitivity analyses exhibiting incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) at the lower and upper estimates of data inputs on the combination of N-acetylcysteine (NAC) and pirfenidone based on (A) quality-adjusted life year (QALY) (B) disability-adjusted life year (DALY) and (C) mortality. The diagram represented the association of variables with the ICERs of interventions vs. placebo. The vertical blue line in the middle represented the ICERs in the base-case analyses. Key parameters were arranged by magnitude of influence on the ICERs.

Fig. 5.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves and scatter plots of all treatment options for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves were displayed based on (A) quality-adjusted life year (QALY) (B) disability-adjusted life year (DALY) and (C) mortality. Cost-effectiveness scatter plots were displayed based on (D) QALY, (E) DALY and (F) mortality. Abbreviations: NAC, N-acetylcysteine.

Discussion

In our study, we integrated direct and indirect evidence from 51 publications, 53 trials, comprising 12,551 individuals with IPF, for evaluating the relative efficacy, tolerability and cost-effectiveness of all currently available drug strategies and offered a rank order to seek the optimum intervention through NMA and cost-effectiveness analysis. Overall, a majority of regimens presented sufficient efficiency and good tolerance compared with placebo or no treatment, however with evidently discrepant financial burden of disease.

The findings from the NMA indicated that, NAC + pirfenidone and pirfenidone appeared to be superior to alleviate all-cause mortality in both effectiveness and tolerability. In terms of decreasing acute exacerbation, NAC + pirfenidone, pirfenidone, nintedanib and imatinib were considered better efficacious and tolerable. With respect to reducing progression of disease, pirfenidone and bosentan implied better in either efficacy or tolerance. NAC, nintedanib + sildenafi and pirfenidone, might significantly reverse lung function decline. We appraised the effectiveness and safety of drug therapies for IPF through comprehensive analysis of these outcomes in NMA, and indicated that pirfenidone and NAC + pirfenidone were considered better efficacious and tolerable.

In our analysis, imatinib might show slight advantage in reducing the incidence of acute exacerbation. However, no benefits were observed in key indicators, such as mortality, disease progression and lung function (DLCO, FVC, 6MWD, etc). These results were generally consistent with current RCT and guidelines, which have proposed a strong recommendation against the use of imatinib.65,66 Similarly, the NMA presented that bosentan might alleviate disease progression, and data from BUILD-159 and BUILD-367 suggested an improvement in disease progression. However, no benefits were discovered in other major parameters, and the guidelines have proposed a conditional recommendation against the use of bosentan.65

Therapeutic effect of NAC monotherapy for IPF in our NMA was consistent with the previous RCTs,68,69 indicating a significant improved 6MWD, while no difference was found in mortality, acute exacerbation and other outcomes, and the guidelines have proposed a conditional recommendation against the use of NAC monotherapy.65 However, after integrating with the results of pharmacoeconomic analysis through Markov model (simulation with a larger sample size and longer period), NAC was suggested as a minimum cost agent owing to the relatively cheap price compared with other drugs.

The cost-effectiveness analysis attempted to bring together the evidence on clinical effectiveness and costs. Our analysis recommended NAC and NAC plus pirfenidone as the cost-effective strategy based on QALY, DALY and mortality. NAC was the minimum cost agent, with a overall cost of $171,199. Compared with placebo, NAC + pirfenidone improved effectiveness by prolonging 7.02 QALYs, and reducing 7.10 DALYs and 8.40 death; and raised a overall cost by $516,894, resulting in ICERs of $73,632 per QALY, $72,802 per DALY and $61,535 per death, respectively. NAC plus pirfenidone was associated with the highest probability being cost-effective at WTP thresholds of $150,000 and $200,000. Sensitivity analyses implied WTP threshold as an influential factor, in short, when assuming the WTP to be low ($40,000–$90,000 approximately) or high ($140,000–$300,000 approximately), the most cost-effective agent for IPF was NAC or NAC + pirfenidone.

Our findings about the overall efficacy and safety of IPF regimens are generally consistent with the NMA published by Pitre et al. (2021)23 in Thorax with 48 cohort studies and RCTs identified, and revealed that nintedanib, pirfenidone and sildenafil alleviated mortality; nintedanib, nintedanib + sildenafil, pirfenidone, pamrevlumab and pentraxin reduced decline of overall FVC. Moreover, our study paid more attention on health utility values for further economic evaluation on medical treatments of IPF. Previous evidence of pharmacoeconomic analysis on IPF medication was insufficient, with limited number of drugs and trials, and the results were greatly influenced by regional differences. Porte et al. (2018)19 reported that, nintedanib appeared to be a more cost-efficient therapeutic option than pirfenidone, however Clay et al. (2019)70 reached an opposite conclusion, both in a French setting. Rinciog et al. (2020)71 implied nintedanib to be more cost-saving than pirfenidone assuming a Belgian healthcare payer perspective. In addition, Dempsey et al. (2021)14 suggested that nintedanib and pirfenidone were not considered cost-effective compared with symptom management for IPF in the United States due to their high price.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first evaluation of all currently available drug strategies for treatment of IPF, that has offered a rank order for options on the balance of efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness, which comports better with the needs of clinical medication for policy makers, clinicians, and patients.

We performed a comprehensive retrieval to acquire universal profiles of the present research findings, and focused on health utility parameters of IPF. Network approach achieved the integration of direct and indirect evidence facilitating to raise the statistical extension of data. The certainty of evidence was appraised by GRADE approach offering an explicit level for decision makers. Large sample size, magnitude of estimate, stable sensitivity, and high consistency between direct and indirect evidence reinforced the confidence in findings. For pharmacoeconomic study, Markov model simulated the multi-states of IPF, reflecting the general process of disease. We considered DALYs from the GBD Study 2017 published by The Lancet,45 providing a basis on drug selection for medical insurance policy. Intuitive evaluation combined with objective indicators arrived at a rational conclusion.

The evaluation has several clinical implications. Our finding suggested that NAC plus pirfenidone could be considered as a cost-effective option for treatment of IPF, however, current ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guidelines1,2 have not addressed the application of this therapy, which may provide evidence for development of prescribing guidelines for rational drug use. Nintedanib has exhibited advantages in decreasing acute exacerbation and reversing lung function, and received a conditional recommendation for use in guidelines, while we do not make a priority proposition in the present investigation after comprehensive consideration of patients’ life time prognosis and its high price.

The findings of our research should be interpreted regarding the following deficiencies. First, NMA shared finiteness of the retrieved individual literature. Potential performance and detection bias within some articles, might be taken into account when understanding the results. Baseline differences undermined the comparability and transferability of data. To seek deviation, we conducted baseline analyses across trials with no statistical significance reported, indicating no major causes of concern. It might be noted that substantial between-study heterogeneity was observed in several treatments, such as NAC.

Second, clinical interpretation of this NMA was influenced by the extent of comprehension of indirect evidence. Although leading network inconsistency was not detected in most comparisons for primary endpoints, the results should be interpreted cautiously and more head-to-head evidence is required. In addition, findings of the research are limited on account of the restricted number of trials in some nodes, and the small sample size in some trials. Moreover, the ranking of potentiality for treatment of IPF might be comprehended modestly owing to a considerable number of comparisons across interventions failing to achieve statistical superiority. Sensitivity analysis on the risk of bias indicated that, nintedanib and pirfenidone may introduce significant bias in some parameters, which should be noticed.

Third, the expression of utility scores of quality of life differed among trials. EQ-5D was preferentially considered for estimating QALYs when available, otherwise, SGRQ was extracted and converted by equation. QALY data were derived from RCTs enrolled in our NMA, which might overlook information from non-pharmaceutical treatment. Furthermore, some RCTs didn't reported the progression rate of disease, we reckoned it as the absolute decline in FVC ≥5% predicted.

Fourth, our results are limited by the constraints of Markov model. The length of follow-up in the trials concerning the NMA was clustered around 12–24 months, while our cost-effectiveness analysis made a much longer projections (US life-tables) confined to the short-term trial evidence. Fortunately, the current Markov model, which informed assumptions about health state transitions and treatment pathways, seemed to be insensitive to time horizon.

Fifth, it should be noted that long-term safety of IPF regimens is complicated and unclear owing to the wide variety and great difference of adverse drug reactions involved, which may introduce considerable uncertainty in model input. Besides, in sensitivity analyses of pharmacoeconomics, for parameters missing plausible ranges of variation, a unified variance of plus or minus 25% from mean values was assumed. This range may have been inaccurate for some variables, notwithstanding, the measure is commonly applied in pharmacoeconomic evaluations.

Finally, disparities in currency form and drug pricing should be noticed for application when generalising to other geographic regions. Additionally, some novel targeting agents, for example pamrevlumab, were eliminated from economic investigation for the absence of drug price, in spite of the advantageous efficacy for IPF. Subpopulations in economic evaluation were not discussed for lack of elaborate evidence.

In conclusion, the NMA and cost-effectiveness analysis informed that the optimal drug therapies for treatment of IPF was the combination of NAC and pirfenidone at WTP thresholds of $150,000 and $200,000. Large well-designed and multi-centre trials, addressing adverse events rate and quality of life under multifarious conditions, are warranted to provide a better picture of IPF management in the further studies.

Contributors

ZCY contributed to conceptualisation, data curation, formal analysis, writing - original draft and writing - review & editing. YY contributed to data curation, formal analysis and writing - original draft. ZCR contributed to data curation, formal analysis, methodology, validation and writing - original draft. ZM contributed to data curation, formal analysis, validation and writing - original draft. JTL contributed to data curation, formal analysis, methodology, validation and writing - original draft. LZH contributed to data curation, methodology and writing - original draft. CJY contributed to conceptualisation, methodology, software, supervision and writing - review & editing. All authors accessed and verified the underlying data, reviewed and approved the final manuscript. CJY was responsible for the decision to submit the manuscript.

Data sharing statement

Data are available from the primary research papers, which are listed in the references. Extracted data are available on request to the corresponding author.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102071.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Raghu G., Remy-Jardin M., Richeldi L., et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (an update) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis in adults: an official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205(9):e18–e47. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202202-0399ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raghu G., Collard H.R., Egan J.J., et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(6):788–824. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2009-040GL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hutchinson J., Fogarty A., Hubbard R., McKeever T. Global incidence and mortality of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a systematic review. Eur Respir J. 2015;46(3):795–806. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00185114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.King C.S., Nathan S.D. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: effects and optimal management of comorbidities. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5(1):72–84. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30222-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.GBD Chronic Respiratory Disease Collaborators Prevalence and attributable health burden of chronic respiratory diseases, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(6):585–596. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30105-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raghu G., Chen S.Y., Yeh W.S., et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in US Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and older: incidence, prevalence, and survival, 2001-11. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(7):566–572. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richeldi L., Collard H.R., Jones M.G. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lancet. 2017;389(10082):1941–1952. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raghu G., Remy-Jardin M., Myers J.L., et al. Diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198(5):e44–e68. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201807-1255ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Somogyi V., Chaudhuri N., Torrisi S.E., Kahn N., Müller V., Kreuter M. The therapy of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: what is next? Eur Respir Rev. 2019;28(153) doi: 10.1183/16000617.0021-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kreuter M., Swigris J., Pittrow D., et al. Health related quality of life in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in clinical practice: insights-IPF registry. Respir Res. 2017;18(1):139. doi: 10.1186/s12931-017-0621-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richeldi L., Fernández Pérez E.R., Costabel U., et al. Pamrevlumab, an anti-connective tissue growth factor therapy, for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (PRAISE): a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(1):25–33. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30262-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.King T.E., Jr., Bradford W.Z., Castro-Bernardini S., et al. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22):2083–2092. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richeldi L., du Bois R.M., Raghu G., et al. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22):2071–2082. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dempsey T.M., Thao V., Moriarty J.P., Borah B.J., Limper A.H. Cost-effectiveness of the anti-fibrotics for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the United States. BMC Pulm Med. 2022;22(1):18. doi: 10.1186/s12890-021-01811-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collard H.R., Ward A.J., Lanes S., Cortney Hayflinger D., Rosenberg D.M., Hunsche E. Burden of illness in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Med Econ. 2012;15(5):829–835. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2012.680553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fan Y., Bender S.D., Conoscenti C.S., et al. Hospital-based resource use and costs among patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis enrolled in the idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis prospective outcomes (IPF-PRO) registry. Chest. 2020;157(6):1522–1530. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collard H.R., Chen S.Y., Yeh W.S., et al. Health care utilization and costs of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in U.S. Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and older. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(7):981–987. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201412-553OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rinciog C., Watkins M., Chang S., et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the UK. Pharmacoeconomics. 2017;35(4):479–491. doi: 10.1007/s40273-016-0480-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Porte F., Cottin V., Catella L., Luciani L., Le Lay K., Bénard S. Health economic evaluation in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in France. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(10):1731–1740. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2018.1433143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):89. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Page M.J., Moher D., Bossuyt P.M., et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n160. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hutton B., Salanti G., Caldwell D.M., et al. The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(11):777–784. doi: 10.7326/M14-2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pitre T., Mah J., Helmeczi W., et al. Medical treatments for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Thorax. 2022;77(12):1243–1250. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2021-217976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raghu G. Interstitial lung disease: a diagnostic approach. Are CT scan and lung biopsy indicated in every patient? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151(3 Pt 1):909–914. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.3.7881691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgins J.P., Altman D.G., Gøtzsche P.C., et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guyatt G., Oxman A.D., Sultan S., et al. GRADE guidelines: 11. Making an overall rating of confidence in effect estimates for a single outcome and for all outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(2):151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelly H., Cowling B.J. Case fatality: rate, ratio, or risk? Epidemiology. 2013;24(4):622–623. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318296c2b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bakbergenuly I., Hoaglin D.C., Kulinskaya E. Estimation in meta-analyses of mean difference and standardized mean difference. Stat Med. 2020;39(2):171–191. doi: 10.1002/sim.8422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rücker G., Schwarzer G., Carpenter J.R., Schumacher M. Undue reliance on I(2) in assessing heterogeneity may mislead. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Higgins J.P., Thompson S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.IntHout J., Ioannidis J.P., Borm G.F. The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method for random effects meta-analysis is straightforward and considerably outperforms the standard DerSimonian-Laird method. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Veroniki A.A., Jackson D., Viechtbauer W., et al. Methods to estimate the between-study variance and its uncertainty in meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2016;7(1):55–79. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dias S., Sutton A.J., Welton N.J., Ades A.E. Evidence synthesis for decision making 3: heterogeneity--subgroups, meta-regression, bias, and bias-adjustment. Med Decis Making. 2013;33(5):618–640. doi: 10.1177/0272989X13485157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin L. Comparison of four heterogeneity measures for meta-analysis. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020;26(1):376–384. doi: 10.1111/jep.13159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salanti G., Ades A.E., Ioannidis J.P. Graphical methods and numerical summaries for presenting results from multiple-treatment meta-analysis: an overview and tutorial. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(2):163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chaimani A., Higgins J.P., Mavridis D., Spyridonos P., Salanti G. Graphical tools for network meta-analysis in STATA. PLoS One. 2013;8(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Begg C.B., Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duval S., Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Higgins J.P., Jackson D., Barrett J.K., Lu G., Ades A.E., White I.R. Consistency and inconsistency in network meta-analysis: concepts and models for multi-arm studies. Res Synth Methods. 2012;3(2):98–110. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dias S., Welton N.J., Caldwell D.M., Ades A.E. Checking consistency in mixed treatment comparison meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2010;29(7–8):932–944. doi: 10.1002/sim.3767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turk F. Data generalizability, data transferability, and the political economy of pharmacoeconomic guidelines. Value Health. 2010;13(8):863–864. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2010.00766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Husereau D., Drummond M., Petrou S., et al. Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards (CHEERS) statement. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2013;29(2):117–122. doi: 10.1017/S0266462313000160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.World Health Organization World health statistics 2022: monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240051157 [Cited 2023 February 26]. Available from:

- 44.Starkie H.J., Briggs A.H., Chambers M.G., Jones P. Predicting EQ-5D values using the SGRQ. Value Health. 2011;14(2):354–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789–1858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Higgins J.P., Thompson S.G., Deeks J.J., Altman D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sanders G.D., Neumann P.J., Basu A., et al. Recommendations for conduct, methodological practices, and reporting of cost-effectiveness analyses: second panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. JAMA. 2016;316(10):1093–1103. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.12195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hultkrantz L. Discounting in economic evaluation of healthcare interventions: what about the risk term? Eur J Health Econ. 2021;22(3):357–363. doi: 10.1007/s10198-020-01257-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao Y., Feng H.M., Qu J., Luo X., Ma W.J., Tian J.H. A systematic review of pharmacoeconomic guidelines. J Med Econ. 2018;21(1):85–96. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2017.1387118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 2022 ASP drug pricing. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-part-b-drug-average-sales-price/2022-asp-drug-pricing-files [Cited 2023 February 26].

- 51.U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 2023 Medicare physician fee schedule-federal regulation notices CMS-1770-P. https://www.cms.gov/medicaremedicare-fee-service-paymentphysicianfeeschedpfs-federal-regulation-notices/cms-1770-p [Cited 2023 February 26].

- 52.Yu Y.F., Wu N., Chuang C.C., et al. Patterns and economic burden of hospitalizations and exacerbations among patients diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(4):414–423. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.4.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dowman L., Hill C.J., May A., Holland A.E. Pulmonary rehabilitation for interstitial lung disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;2(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006322.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cantor S.B. Cost-effectiveness analysis, extended dominance, and ethics: a quantitative assessment. Med Decis Making. 1994;14(3):259–265. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9401400308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Neumann P.J., Cohen J.T., Weinstein M.C. Updating cost-effectiveness--the curious resilience of the $50,000-per-QALY threshold. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(9):796–797. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1405158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Woods B., Revill P., Sculpher M., Claxton K. Country-level cost-effectiveness thresholds: initial estimates and the need for further research. Value Health. 2016;19(8):929–935. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hatswell A.J., Bullement A., Briggs A., Paulden M., Stevenson M.D. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis in cost-effectiveness models: determining model convergence in cohort models. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36(12):1421–1426. doi: 10.1007/s40273-018-0697-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mohindru B., Turner D., Sach T., et al. Health state utility data in cystic fibrosis: a systematic review. Pharmacoecon Open. 2020;4(1):13–25. doi: 10.1007/s41669-019-0144-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.King T.E., Jr., Behr J., Brown K.K., et al. BUILD-1: a randomized placebo-controlled trial of bosentan in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(1):75–81. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200705-732OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Behr J., Kolb M., Song J.W., et al. Nintedanib and sildenafil in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and right heart dysfunction. A prespecified subgroup analysis of a double-blind randomized clinical trial (INSTAGE) Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(12):1505–1512. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201903-0488OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arai T., Tachibana K., Sugimoto C., et al. High-dose prednisolone after intravenous methylprednisolone improves prognosis of acute exacerbation in idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Respirology. 2017;22(7):1363–1370. doi: 10.1111/resp.13065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aso S., Matsui H., Fushimi K., Yasunaga H. Systemic glucocorticoids plus cyclophosphamide for acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a retrospective nationwide study. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2019;36(2):116–123. doi: 10.36141/svdld.v36i2.7181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hozumi H., Hasegawa H., Miyashita K., et al. Efficacy of corticosteroid and intravenous cyclophosphamide in acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a propensity score-matched analysis. Respirology. 2019;24(8):792–798. doi: 10.1111/resp.13506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kawamura K., Ichikado K., Yasuda Y., Anan K., Suga M. Azithromycin for idiopathic acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a retrospective single-center study. BMC Pulm Med. 2017;17(1):94. doi: 10.1186/s12890-017-0437-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Raghu G., Rochwerg B., Zhang Y., et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline: treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An update of the 2011 clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(2):e3–e19. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201506-1063ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Daniels C.E., Lasky J.A., Limper A.H., et al. Imatinib treatment for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: randomized placebo-controlled trial results. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(6):604–610. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200906-0964OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.King T.E., Jr., Brown K.K., Raghu G., et al. BUILD-3: a randomized, controlled trial of bosentan in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(1):92–99. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201011-1874OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Homma S., Azuma A., Taniguchi H., et al. Efficacy of inhaled N-acetylcysteine monotherapy in patients with early stage idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirology. 2012;17(3):467–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2012.02132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Clinical Research Network. Martinez F.J., de Andrade J.A., Anstrom K.J., King T.E., Jr., Raghu G. Randomized trial of acetylcysteine in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22):2093–2101. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Clay E., Cristeau O., Chafaie R., Pinta A., Mazaleyrat B., Cottin V. Cost-effectiveness of pirfenidone compared to all available strategies for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in France. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2019;7(1) doi: 10.1080/20016689.2019.1626171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rinciog C., Diamantopoulos A., Gentilini A., et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of nintedanib versus pirfenidone in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in Belgium. Pharmacoecon Open. 2020;4(3):449–458. doi: 10.1007/s41669-019-00191-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.