Version Changes

Revised. Amendments from Version 1

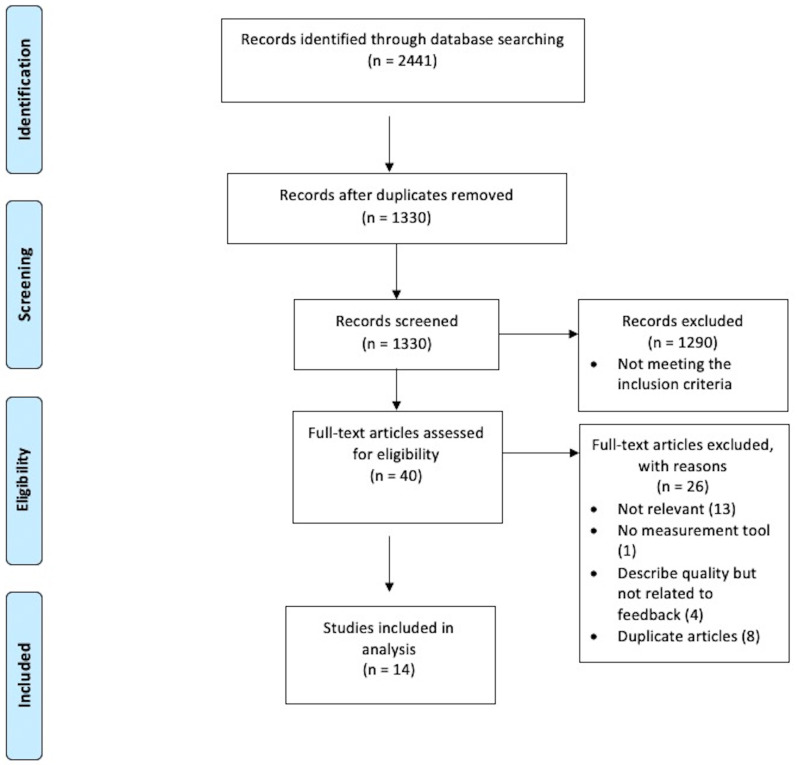

In this updated version of the manuscript "A Systematic Review of Effective Quality Feedback Measurement Tools Used in Clinical Skills Assessment", we have made several revisions to address the reviewers' feedback. Firstly, we have clarified our study scoring methodology in the paper. The process involves a panel of four reviewers independently evaluating each study. If a determinant was explicitly addressed within the study, a plus score (+) was assigned, with multiple plus scores (++ or +++) indicating a stronger presence of a determinant. Conversely, an unaddressed or absent determinant was assigned a minus score (-), with multiple minus scores (-- or ---) indicating a noteworthy absence. Each study received an aggregate score based on these evaluations. This revised description enhances the transparency of our scoring methodology. Secondly, we improved the clarity of the caption for Figure 1. The revised caption now reads: "Flow diagram illustrating the study selection process employed in this systematic review, guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines 27." This change provides a clearer explanation of the figure's content and its relation to the PRISMA guidelines. Lastly, we added a summarizing statement about what the study brings to the field. We underscored the importance of the quality of written feedback in clinical skills assessments, highlighting its distinctive value as an independent instructional tool. Even though written feedback does not involve direct conversations with learners, it still requires specificity, constructiveness, and actionability to guide learners' self-improvement effectively. This statement illuminates the importance of ensuring these parameters in written feedback, reinforcing its role in the holistic educational experience of learners in the medical field. These updates have strengthened our manuscript and clarified previously ambiguous points or lacking detail.

Abstract

Background:

Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) is a valid tool to assess the clinical skills of medical students. Feedback after OSCE is essential for student improvement and safe clinical practice. Many examiners do not provide helpful or insightful feedback in the text space provided after OSCE stations, which may adversely affect learning outcomes. The aim of this systematic review was to identify the best determinants for quality written feedback in the field of medicine.

Methods:

PubMed, Medline, Embase, CINHAL, Scopus, and Web of Science were searched for relevant literature up to February 2021. We included studies that described the quality of good/effective feedback in clinical skills assessment in the field of medicine. Four independent reviewers extracted determinants used to assess the quality of written feedback. The percentage agreement and kappa coefficients were calculated for each determinant. The ROBINS-I (Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions) tool was used to assess the risk of bias.

Results:

14 studies were included in this systematic review. 10 determinants were identified for assessing feedback. The determinants with the highest agreement among reviewers were specific, described gap, balanced, constructive and behavioural; with kappa values of 0.79, 0.45, 0.33, 0.33 and 0.26 respectively. All other determinants had low agreement (kappa values below 0.22) indicating that even though they have been used in the literature, they might not be applicable for good quality feedback. The risk of bias was low or moderate overall.

Conclusions:

This work suggests that good quality written feedback should be specific, balanced, and constructive in nature, and should describe the gap in student learning as well as observed behavioural actions in the exams. Integrating these determinants in OSCE assessment will help guide and support educators for providing effective feedback for the learner.

Keywords: Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE), effective feedback, measurement, quality, determinant, Kappa.

Introduction

During their undergraduate education, medical and health sciences students are subjected to numerous clinical practical assessments in order to evaluate their performance 1 . Feedback is a fundamental and important learning tool in medical education 2 . Good and effective feedback assists students in accomplishing both learning and professional development, enhancing student motivation and satisfaction 3– 5 . The Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) is a commonly utilized clinical skills assessment in medical and health sciences that has a positive impact on medical education 6 . OSCE is useful in the field of medicine for evaluating student performance for a variety of reasons; the OSCE will simulate the realities of clinical practice, enhancing students' confidence and ensuring safe clinical practice, with assessment based on objective determinants 7– 10 . The OSCE is a valid and reliable assessment tool in a variety of fields, including medicine 9, 11– 15

During the OSCE, examiners are requested to input the students' observed marks on score sheets (without knowing total marks) and can also provide their professional opinion on students’ performance using the Global Rating Scale (GRS) (Fail, Borderline, Pass, Good, Excellent) based on experience 16, 17 . Previous research has shown a mismatch between observed Marks and GRS 18 . For example, the student may score a high result in the observation section, but receive a ‘fail’ for their Global Rating Score and potentially vice versa.

However, written feedback for OSCE is optional, despite previous research showing it to have a significant positive impact on student's learning outcomes 19, 20 . It is argued that many examiners may find it difficult to offer detailed or useful written feedback during OSCE evaluation 21, 22 due to time constraints as well as a ‘judgement dilemma’ of not knowing how much feedback or the type of feedback to give 23 .

Even if written feedback is provided, to date there is no recognised objective measurement scoring tool that measures the quality of written feedback from the OSCE. Measuring the quality of written feedback will help examiners to improve their skills in feedback delivery, as well as encourage students to understand the OCSE marks they received and where they can improve in the future. In other fields of education, feedback quality measurement tools are used effectively to improve the quality of written feedback for students 24– 26 . In order to develop such a tool, it is necessary to identify the determinants that result in effective written feedback. The main objectives of this systematic review are to identify and evaluate studies that have measured written feedback quality.

Methods

Study design

This a comprehensive systematic review to identify the most relevant determinants that describe good and effective written feedback in the field of medicine. Measurement tools that measure feedback quality both quantitatively and qualitatively will be included.

Search strategy and publication sources

CINHAL, PubMed, Medline, Embase, Scopus and Web of Science were searched for relevant studies published from January 2010 until February 2021. We used the following keywords: “OSCE “, “objective structured clinical examination*”, “medical student*”, “medical education”, “clinical skill*”, “clinical setting.” AND “formative feedback “, “constructive feedback”, “effective feedback”, “qualitative feedback”, AND “quality “, “scoring”, “measurement*/ measuring”, “assessment*/ assessing”.

We sought assistance from a university librarian to enhance our search strategy. The reference section of initially selected studies was also searched thoroughly for any additional relevant publications. A bibliographical database was created to store and manage the references.

Selection of articles

Each author independently screened retrieved articles against inclusion and exclusion criteria, and as a team agreed on the included studies. Following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines 27 , only studies written in the English language, published in the last 10 years in the field of medicine were included. Both quantitative and qualitative studies were included. Studies were included if they described the quality of good/effective feedback in clinical skills assessment, or attempted to evaluate the quality of feedback in clinical skills assessment (e.g., OSCE), or described the quality of written feedback by enumerating determinants of effective feedback involving undergraduate students and postgraduate trainees. Exclusion criteria included papers not written in English language, case reports, ‘grey literature’ (which includes conference proceeding studies) and commentaries. Due to different cognitive demands and scopes of practice, publications relating to nursing, paramedical disciplines, pharmacy, and veterinary education were excluded ( Figure 1). Reference lists of included studies were also explored to identify any additional studies.

Figure 1. Flow diagram showing study selection process based on Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis guidelines 27 .

Data extraction

Four independent reviewers (A.A, D.L, M.N and T.K) identified and extracted the determinants used to evaluate written feedback from the included studies ( Table 1). An accumulated list of identified determinants and their respective definitions was compiled. Each reviewer then scored each of the included studies against the accumulated list of determinants. The approach involved a panel of four reviewers who independently evaluated each study. A determinant was assigned a plus score (+) if it was explicitly addressed within the study, with multiple plus scores (++ or +++) for a stronger presence of a determinant. Conversely, an unaddressed or absent determinant was assigned a minus score (-), with multiple minus scores (-- or ---) if the absence was particularly noteworthy. This led to each study receiving an aggregate score.

Table 1. The 10 determinants of feedback quality measurement identified.

| Determinant of

feedback measurement |

General description | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Specific | Detailed information of what was done well or poorly. |

| 2 | Balanced | Contains both positive and negative comments. |

| 3 | Behavioural | Observed action in exam (not personal). |

| 4 | Timely | Given immediately after assessment is completed. |

| 5 | Constructive | Supportive feedback identifying a solution to area of weakness they may have. |

| 6 | Quantifiable | Feedback that can be used to develop detailed statistical data. |

| 7 | Focused | Feedback that is given around key results. |

| 8 | Described task | Focuses the knowledge and skills associated with a task: sufficient or insufficient. |

| 9 | Described gap | Detailed about what is missing in the task. |

| 10 | Described action plan | Detailed plan of action needed to reach one or more goals. |

Statistical analysis

Level of agreement scores (%) and Kappa coefficients between the reviewers were calculated for each determinant included. Both level of agreement and kappa were measured using an online calculator ( http://justusrandolph.net/kappa/) 28 . Percentage agreement calculates agreement by chance which is corrected for by calculating kappa. The average Kappa coefficients were interpreted as follows: <0 indicates no agreement, 0.01–0.20 indicates slight or poor agreement, 0.21–0.40 indicates fair agreement, 0.41–0.60 indicates moderate agreement, 0.61–0.80 indicates substantial agreement, and 0.81–1.00 indicates almost perfect agreement 29 . Determinants with the highest Kappa were identified as being most useful for providing written feedback for OSCE. In addition, included studies were assessed to identify which studies were best for measuring the quality of feedback.

Risk of bias and certainty assessment

Two independent reviewers used the ROBINS-I (Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions) tool to assess the risk of bias of each included study ( Table 3). Confounding, selection, classification, intervention, missing data, measurement, and reporting were all checked for bias. The ROBINS-I was used to assess the certainty in the body of evidence in the context of GRADE's (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations) approach 30, 31 .

When there were any conflicts, the entire review team was consulted, and the disagreements were then addressed by consensus.

Results

Search results

The initial search yielded 2441 studies ( Figure 1). After the duplicates were removed, 1330 studies remained. 1290 studies were found to be irrelevant to the main topic after scanning the title and abstract. The 40 remaining articles were thoroughly evaluated by reading the full text. A further 26 articles 2, 7, 21– 23, 32– 44 were removed leaving 14 studies for inclusion in this systematic review ( Figure 1).

Content analysis

Of the 14 studies included, 7 were conducted in the United States 23, 45– 50 , 2 each in the United Kingdom 51, 52 , and Canada 53, 54 , and 1 each in the Netherlands 55 , Switzerland 56 , and South Africa 19 respectively. Half of the studies involved medical students (undergraduate setting) 46, 48, 49, 51, 53– 55 , and the other half involved medical residents (postgraduate setting) 19, 45, 47, 50, 52, 56, 57 . 10 of the 14 studies used a scoring system or systematic framework for evaluating the quality of written feedback 19, 45, 48– 54, 57 , while the other 4 studies had no scoring system 46, 47, 55, 56 . Only 2 studies were conducted in multiple institution contexts 48, 50 , while 12 were conducted in a single institution 19, 45– 47, 49, 51– 57 setting.

Determinants identified

A total of 10 determinants to assess the quality of written feedback were identified from the combined 14 studies ( Table 1).

Each reviewer then scored each of the 14 included studies against the accumulated list of determinants ( Table 2).

Table 2. Scoring by reviewers for determinants of quality of written feedback.

| Year | Specific | Balanced | Behavioral | Timely | constructive | Quantifiable | Focused | Describe

Task |

Describe

gap |

Describe

Action plan |

Overall

agreement % (Studies) |

Kappa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camarata, T.

et al. 45 |

2020 | + + + + | + + + + | - + + - | - + + + | + + + + | + +

+ + |

- - + - | - - - + | - - - + | - + + - | 66.7 | 0.33 |

| Tekian, A.

et al. 46 |

2019 | + + + + | - + + + | - + + + | - - - - | - + + + | + - + + | - - + - | - - + + | - - - - | - - - - | 68.3 | 0.37 |

| Tomiak. A

et al. 53 |

2019 | + + + + | - - - - | + + + + | + + + + | + + + + | - + + - | + + + + | - + + + | - + - + | + + - + | 78.3 | 0.57 |

| Page, M.

et al. 51 |

2019 | + + + + | - - + + | - + + + | - - + + | + + + + | + +

+ + |

- - + + | - + + - | - - - - | - + - - | 63.3 | 0.27 |

| Abraham, R.

et al. 19 |

2019 | + + + + | - - + - | - + + + | - - + + | - + + - | + +

+ + |

- - + - | + + + + | + + + + | + + + + | 71.7 | 0.43 |

| Dallaghan, G.

et al. 47 |

2018 | + + + + | - - + - | + + + + | - - + + | - - + + | - - + - | - - + - | - + - + | - - - - | + + - - | 58.3 | 0.17 |

| Karim, A.

et al. 48 |

2017 | + + + + | - + + + | - + + + | - - + + | - + + + | - - + + | + - + - | - + + + | - - - - | + + - - | 53.3 | 0.07 |

| Gullbas, L.

et al. 57 |

2016 | + - + + | - + + + | + + + + | - - + - | + - + + | - - - + | - - + - | - - - - | - - - - | + - - - | 65.0 | 0.30 |

| Junod, N.

et al. 56 |

2016 | + + + - | + + + + | + + + + | - - + + | - + + + | - + + + | - - + + | - - - + | - + + - | - + + - | 53.3 | 0.07 |

| Nesbitt, A.

et al. 52 |

2014 | - + + + | - + - - | - - + + | - - + - | - - + + | - - - - | - + + - | + - - + | + + + + | + - + - | 51.7 | 0.03 |

| Jackson, J.

et al. 49 |

2014 | + + + + | + + + + | + + + + | - - + - | + + + + | + + - + | - + + + | - - - + | + - + - | + + - + | 68.3 | 0.37 |

| Gauthier, S.

et al. 54 |

2014 | + + + + | - - - - | - - + + | - - - - | - - - - | + +

+ + |

- - + - | + + + + | + + + + | + + + + | 88.3 | 0.77 |

| Pelgrim, E.

et al. 55 |

2012 | + + + + | - + - - | - - + + | - - + + | - - + + | - + + - | - + + - | - + + + | - + + - | + + + + | 50.0 | 0.00 |

| Canavan, C.

et al. 50 |

2010 | + + + + | - + + + | + + + + | - - + - | - - + + | - - + - | + + + - | - + + + | - + + - | - + - - | 56.7 | 0.13 |

| Overall

agreement % (determinants) |

89.3 | 66.7 | 66.7 | 53.6 | 61.9 | 64.3 | 47.6 | 56 | 72.6 | 58.3 | |||

| Kappa | 0.79 | 0.33 | 0.26 | 0.07 | 0.33 | 0.20 | - 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.45 | 0.17 | -------- | ------ |

The number of determinants identified in the individual studies ranged from 7 to 10 respectively. The determinants with the highest agreement (kappa values) among reviewers were Specific (0.79 - substantial agreement), Described gap (0.45 moderate agreement), Balanced (0.33 - fair agreement), Constructive (0.33 - fair agreement), and Behavioural (0.26 - fair agreement) respectively. All other determinants had low agreement (kappa values below 0.21 - slight or poor agreement) indicating that even though they have been used in the literature, they might not be applicable for good quality feedback. The identified determinants with highest level of agreement among reviewers were included in seven of the ten studies of which the study by Abraham et al. 19 had the highest level of agreement 19, 28, 32, 33, 35, 38, 39 . ( Table 2).

Risk of bias

We utilized the ROBINS-I score method to analyse bias across confounding bias, selection bias, classifications bias, intervention bias, bias due to missing data, measurement bias, and reporting bias to assess the possible risk of bias ( Table 3). Almost all the studies included had low confounding, selection, and measurement biases. The overall risk of bias was low to moderate for the included studies, which is understandable considering the nonrandomized character of the research and dependence on self-reporting measures. The remaining post-intervention biases were variable, ranging from mild to moderate.

Table 3. Results risk of bias assessment for individual studies using ROBINS-I methods.

| Study | Pre-intervention | At-

intervention |

Post-intervention | Overall

risk of bias |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First author | Year | Bias due to

confounding |

Bias in

selection of participants into the study |

Bias in

classification of interventions |

Bias due to

deviations from intended Interventions |

Bias

due to missing data |

Bias in

measurement of outcomes |

Bias in

selection of the reported result |

low/

moderate/ serious/ critical |

| Camarata 45 | 2020 | low | low | low | moderate | low | low | low | moderate |

| Tekian 46 | 2019 | low | low | low | low | low | low | low | low |

| Tomiak 53 | 2019 | low | low | low | moderate | low | moderate | moderate | moderate |

| Page 51 | 2019 | low | low | low | low | low | low | low | low |

| Abraham 19 | 2019 | low | low | low | low | low | low | low | low |

| Dallaghan 47 | 2018 | Low | moderate | Low | low | moderate | low | moderate | moderate |

| Karim 48 | 2017 | Low | low | Low | low | low | low | low | low |

| Gullbas 57 | 2016 | Low | low | Low | low | low | low | low | low |

| Junod 56 | 2016 | moderate | low | Low | moderate | low | low | low | moderate |

| Nesbitt 52 | 2014 | low | low | Low | moderate | low | moderate | moderate | moderate |

| Jackson 49 | 2014 | low | low | Low | low | low | Low | Low | Low |

| Gauthier 54 | 2014 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Pelgrim 55 | 2012 | Low | Low | Low | Low | moderate | Low | moderate | moderate |

| Canavan 50 | 2010 | Low | Low | Low | moderate | moderate | moderate | moderate | moderate |

Certainty in body of evidence

In systematic reviews, the GRADE working group has created a widely-accepted approach to evaluate the certainty of a body of evidence-based on a four-level system: high, moderate, low and very low. The current GRADE strategy for a body of evidence linked to interventions starts by categorizing studies into one of two groups: randomized controlled trials (RCT) or observational studies (also non-randomized studies, or NRS). The body of evidence begins with high certainty if the relevant research is randomized trials. The body of evidence begins with a low level of certainty if the relevant study is observational 31, 58 .

Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was to evaluate studies that have measured the quality of written feedback for clinical exams and identify which determinants should be used to provide quality written feedback. Improving the quality of written feedback for students in the field of medicine will improve student performance.

Four independent researchers critically appraised 14 studies using 10 identified determinants. The five determinants with the highest Kappa values were: (1) Specific: tutors should include details in the comment section about what the student has done in the clinical exam (Kappa 0.79); (2) Described gap: the comment should include points about what was missing in the task (Kappa 0.45) 59 ; Balanced: the comment should include both positive and negative statements about the student's performance (Kappa 0.33); (4) Constructive feedback: the comment should identify an area of improvement and give a solution to the student (Kappa 0.33); and (5) Behavioural: the comment should include observed (not personal) action in the exam (Kappa 0.26). The other five determinants were conversely deemed to be lacking in agreement, showing some form of confusion and complexity amongst the reviewers in its ascertainment. Hence, these determinants may not be considered to be a good qualitative measurement element of feedback quality.

The number of determinants in each individual study ranged from seven to ten respectively. The five key determinants appeared in seven of the ten studies in this systematic review. It may be worthwhile to consider including these five key determinants in feedback and performance assessments.

Feedback delivery is influenced by a number of factors. One of them, according to research, is that the examiner lacks the ability to translate his observation into detailed, non-judgmental, and constructive feedback 3, 60 . Therefore, feedback will ultimately be ambiguous and meaningless to students seeking to improve their performance 60 .

Effective feedback tools, from the perspective of educators, should include determinants that aid in the learning process, such as helping students comprehend their subject area and providing clear guidance on how to enhance their learning. Structuring feedback by using the five identified determinants will improve alignment between GRS and observed marks. That will lead to a better understanding GRS in observed marks.

Developing a digital tool to evaluate written feedback from OSCE will help in cases where there is a discrepancy between observed marks and the Global Rating Scale result. In these cases, written feedback can be utilized in case of a pass/fail decision. This could demonstrate the significance of feedback in decision-making, as well as how written feedback is viewed as a learning tool that leads to improvements in student performance. The five identified determinants with the highest kappa values could be used as a method to quantify written feedback. Tutors and educators should be made aware of these determinants prior to the OSCE so that they provide beneficial feedback to students. Having a structured comments section could also help overcome the writing challenges tutors currently face when marking the OSCE.

Further study is needed to categorize determinants and sub classify them as part of a quantification approach. This digital measurement tool in medical education will help improve students' performance and knowledge acquisition.

This systematic review had some limitations. For example, grey literature was not included in the study and we reviewed only English studies which may mean results are not generalizable. Another limitation is the focus on written feedback in one type of clinical skills assessment (OSCE). Future research should also consider other training feedback in postgraduate training as well as undergraduate training.

Conclusion

This work suggests that good quality written feedback should be specific, balanced, and constructive in nature, and should describe the gap in student learning as well as observed behavioural actions in the exams. Integrating these five core determinants in OSCE assessment will help guide and support educators in providing effective and actionable feedback for the learner. Lastly, This study underscores the importance of the quality of written feedback in clinical skills assessments, highlighting its distinctive value as an independent instructional tool. While many studies have evaluated verbal feedback, this research brings to the fore that written feedback exists. However, not being part of direct conversations with learners still demands specificity, constructiveness, and actionability that effectively guides learners' self-improvement. Our work illuminates the criticality of ensuring these parameters in written feedback, reinforcing its role in the holistic educational experience of learners in the medical field.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Rosie Dunne for her assistance in performing this systematic review by explaining how to conduct a scientific search strategy using key relevant words.

The authors acknowledge Moher et al., (2009) for the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) Statement.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declared that no grants were involved in supporting this work.

[version 2; peer review: 2 approved]

Data availability

All data underlying the results are available as part of the article and no additional source data are required.

Reporting guidelines

Zenodo: PRISMA checklist and flow diagram for ‘A systematic review of effective quality feedback measurement tools used in clinical skills assessment. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6003404 61

Data are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC-BY 4.0).

Authors' contributions

AA: took the lead in writing the manuscript and played a key role in systematic literature review. DL: was involved in editing the figures and tables as well as was one of the reviewers in marking the studies. MN: provided a significant input in interpretation of the result as well as manuscript editing. TK: was involved in reviewing, editing and supervising the work. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Notes on contributors

AA, (MBBS, MSc), is a PhD student at the School of Medicine, National University of Ireland, Galway. His research interest is with assessment in medical education. He is a teaching assistant in medical education department, in the college of medicine, of Taif University at Saudi Arabia as well. ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0965-5834

DL, is a Bachelor student at the School of Medicine, National University of Ireland, Galway. Her research interest is with assessment in medical education.

MN, (BA, HDip, MSc, PhD), is the academic director of innovative postgraduate programme in Medical Science and Surgery at National University of Ireland, Galway. His research interests include: exercise rehabilitation for cancer, physiological performance and assessment in sports and exercise, and lifestyle medicine. ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7920-0811

TK, (BSc PT, PPT, MA, MSc, PhD), is a Senior Lecturer in Medical Informatics and Medical Education at the National University of Ireland, Galway. His research interests include postgraduate medical education and continuing professional development. ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7071-3266

References

- 1. Wallace J, Rao R, Haslam R: Simulated patients and objective structured clinical examinations: Review of their use in medical education. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2002;8(5):342–348. 10.1192/apt.8.5.342 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carr S: The Foundation Programme assessment tools: An opportunity to enhance feedback to trainees? Postgrad Med J. 2006;82(971):576–579. 10.1136/pgmj.2005.042366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cantillon P, Sargeant J: Giving feedback in clinical settings. BMJ. 2008;337(7681):a1961. 10.1136/bmj.a1961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rowe A: The personal dimension in teaching: why students value feedback. Int J Educ Manag. 2011;25(4):343–360. 10.1108/09513541111136630 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schartel SA: Giving feedback - an integral part of education. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2012;26(1):77–87. 10.1016/j.bpa.2012.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Patrício MF, Julião M, Fareleira F, et al. : Is the OSCE a feasible tool to assess competencies in undergraduate medical education? Med Teach. 2013;35(6):503–514. 10.3109/0142159X.2013.774330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rush S, Ooms A, Marks-Maran D, et al. : Students' perceptions of practice assessment in the skills laboratory: An evaluation study of OSCAs with immediate feedback. Nurse Educ Pract. 2014;14(6):627–634. 10.1016/j.nepr.2014.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bouchoucha S, Wikander L, Wilkin C: Nurse academics perceptions of the efficacy of the OSCA tool. Collegian. 2013;20(2):95–100. 10.1016/j.colegn.2012.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Selim AA, Ramadan FH, El-Gueneidy MM, et al. : Using Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) in undergraduate psychiatric nursing education: Is it reliable and valid? Nurse Educ Today. 2012;32(3):283–288. 10.1016/j.nedt.2011.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McWilliam PL, Botwinski CA: Identifying strengths and weaknesses in the utilization of objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) in a nursing program. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2012;33(1):35–39. 10.5480/1536-5026-33.1.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gledhill RF, Capatos D: Factors affecting the reliability of an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) test in neurology. S Afr Med J. 1985;67(12):463–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cunnington JP, Neville AJ, Norman GR: The risks of thoroughness: Reliability and validity of global ratings and checklists in an OSCE. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 1996;1(3):227–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brown G, Manogue M, Martin M: The validity and reliability of an OSCE in dentistry. Eur J Dent Educ. 1999;3(3):117–125. 10.1111/j.1600-0579.1999.tb00077.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hodges B: Validity and the OSCE. Med Teach. 2003;25(3):250–254. 10.1080/01421590310001002836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Setyonugroho W, Kennedy KM, Kropmans TJ: Reliability and validity of OSCE checklists used to assess the communication skills of undergraduate medical students: A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(12):1482–1491. 10.1016/j.pec.2015.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Regehr G, MacRae H, Reznick RK, et al. : Comparing the psychometric properties of checklists and global rating scales for assessing performance on an OSCE-format examination. Acad Med. 1998;73(9):993–997. 10.1097/00001888-199809000-00020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rajiah K, Veettil SK, Kumar S: Standard setting in OSCEs: A borderline approach. Clin Teach. 2014;11(7):551–556. 10.1111/tct.12213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pell G, Homer M, Fuller R: Investigating disparity between global grades and checklist scores in OSCEs. Med Teach. 2015;37(12):1106–1113. 10.3109/0142159X.2015.1009425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Abraham RM, Singaram VS: Using deliberate practice framework to assess the quality of feedback in undergraduate clinical skills training. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):105. 10.1186/s12909-019-1547-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ryan T, Henderson M, Ryan K, et al. : Designing learner-centred text-based feedback: a rapid review and qualitative synthesis. Assess Eval High Educ. 2021;46(6):894–912. 10.1080/02602938.2020.1828819 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Archer JC: State of the science in health professional education: Effective feedback. Med Educ. 2010;44(1):101–108. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03546.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Al-Mously N, Nabil NM, Al-Babtain SA, et al. : Undergraduate medical students' perceptions on the quality of feedback received during clinical rotations. Med Teach. 2014;36 Suppl 1:S17–S23. 10.3109/0142159X.2014.886009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wardman MJ, Yorke VC, Hallam JL: Evaluation of a multi-methods approach to the collection and dissemination of feedback on OSCE performance in dental education. Eur J Dent Educ. 2018;22(2):e203–e211. 10.1111/eje.12273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Griffiths JM, Luhanga U, McEwen LA, et al. : Promoting high-quality feedback: Tool for reviewing feedback given to learners by teachers. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62(7):600–602 and e419–e421. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McMahon-Parkes K, Chapman L, James J: The views of patients, mentors and adult field nursing students on patients' participation in student nurse assessment in practice. Nurse Educ Pract. 2016;16(1):202–208. 10.1016/j.nepr.2015.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chapman CL, Burlingame GM, Gleave R, et al. : Clinical prediction in group psychotherapy. Psychother Res. 2012;22(6):673–681. 10.1080/10503307.2012.702512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. : Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339(7716):b2535. 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wray CD, McDaniel SS, Saneto RP, et al. : Is postresective intraoperative electrocorticography predictive of seizure outcomes in children? J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2012;9(5):546–551. 10.3171/2012.1.PEDS11441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McHugh ML: Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2012;22(3):276–282. 10.11613/BM.2012.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. : ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. 10.1136/bmj.i4919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schünemann HJ, Cuello C, Akl EA, et al. : GRADE guidelines: 18. How ROBINS-I and other tools to assess risk of bias in nonrandomized studies should be used to rate the certainty of a body of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;111:105–114. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang S, Soreide KK, Kelling SE, et al. : Quality assurance processes for standardized patient programs. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2018;10(4):523–528. 10.1016/j.cptl.2017.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schartel SA: Giving feedback - An integral part of education. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2012;26(1):77–87. 10.1016/j.bpa.2012.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Norcini J, Burch V: Workplace-based assessment as an educational tool: AMEE Guide No. 31. Med Teach. 2007;29(9):855–871. 10.1080/01421590701775453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Aeder L, Altshuler L, Kachur E, et al. : The "Culture OSCE"--introducing a formative assessment into a postgraduate program. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2007;20(1):11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Burgess A, Mellis C: Receiving feedback from peers: Medical students' perceptions. Clin Teach. 2015;12(3):203–207. 10.1111/tct.12260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bienstock JL, Katz NT, Cox SM, et al. : To the point: medical education reviews--providing feedback. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(6):508–513. 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bing-You R, Hayes V, Varaklis K, et al. : Feedback for Learners in Medical Education: What is Known? A Scoping Review. Acad Med. 2017;92(9):1346–1354. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Busari JO, Weggelaar NM, Knottnerus AC, et al. : How medical residents perceive the quality of supervision provided by attending doctors in the clinical setting. Med Educ. 2005;39(7):696–703. 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02190.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Halman S, Dudek N, Wood T, et al. : Direct Observation of Clinical Skills Feedback Scale: Development and Validity Evidence. Teach Learn Med. 2016;28(4):385–394. 10.1080/10401334.2016.1186552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Solheim E, Plathe HS, Eide H: Nursing students' evaluation of a new feedback and reflection tool for use in high-fidelity simulation - Formative assessment of clinical skills. A descriptive quantitative research design. Nurse Educ Pract. 2017;27:114–120. 10.1016/j.nepr.2017.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ingram JR, Anderson EJ, Pugsley L: Difficulty giving feedback on underperformance undermines the educational value of multi-source feedback. Med Teach. 2013;35(10):838–846. 10.3109/0142159X.2013.804910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schlair S, Dyche L, Milan F, et al. : A faculty development program to prepare instructors to observe and provide effective feedback on clinical skills to internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:S577. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mitchell JD, Ku C, Diachun CAB, et al. : Enhancing Feedback on Professionalism and Communication Skills in Anesthesia Residency Programs. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(2):620–631. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Camarata T, Slieman TA: Improving Student Feedback Quality: A Simple Model Using Peer Review and Feedback Rubrics. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020;7:2382120520936604. 10.1177/2382120520936604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tekian A, Borhani M, Tilton S, et al. : What do quantitative ratings and qualitative comments tell us about general surgery residents' progress toward independent practice? Evidence from a 5-year longitudinal cohort. Am J Surg. 2019;217(2):288–295. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.09.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Beck Dallaghan GL, Higgins J, Reinhardt A: Feedback Quality Using an Observation Form. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2018;5:2382120518777768. 10.1177/2382120518777768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Karim AS, Sternbach JM, Bender EM, et al. : Quality of Operative Performance Feedback Given to Thoracic Surgery Residents Using an App-Based System. J Surg Educ. 2017;74(6):e81–e87. 10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jackson JL, Kay C, Jackson WC, et al. : The Quality of Written Feedback by Attendings of Internal Medicine Residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(7):973–978. 10.1007/s11606-015-3237-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Canavan C, Holtman MC, Richmond M, et al. : The quality of written comments on professional behaviors in a developmental multisource feedback program. Acad Med. 2010;85(10 SUPPL):S106–S109. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ed4cdb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Page M, Gardner J, Booth J: Validating written feedback in clinical formative assessment. Assess Eval High Educ. 2020;45(5):697–713. 10.1080/02602938.2019.1691974 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Nesbitt A, Pitcher A, James L, et al. : Written feedback on supervised learning events. Clin Teach. 2014;11(4):279–283. 10.1111/tct.12145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tomiak A, Braund H, Egan R, et al. : Exploring How the New Entrustable Professional Activity Assessment Tools Affect the Quality of Feedback Given to Medical Oncology Residents. J Cancer Educ. 2020;35(1):165–177. 10.1007/s13187-018-1456-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gauthier S, Cavalcanti R, Goguen J, et al. : Deliberate practice as a framework for evaluating feedback in residency training. Med Teach. 2015;37(6):551–557. 10.3109/0142159X.2014.956059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pelgrim EA, Kramer AW, Mokkink HG, et al. : Quality of written narrative feedback and reflection in a modified mini-clinical evaluation exercise: An observational study. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12(1):97. 10.1186/1472-6920-12-97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Perron NJ, Louis-Simonet M, Cerutti B, et al. : The quality of feedback during formative OSCEs depends on the tutors' profile. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):293. 10.1186/s12909-016-0815-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gulbas L, Guerin W, Ryder HF: Does what we write matter? Determining the features of high- and low-quality summative written comments of students on the internal medicine clerkship using pile-sort and consensus analysis: A mixed-methods study. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:145. 10.1186/s12909-016-0660-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Morgan RL, Thayer KA, Santesso N, et al. : A risk of bias instrument for non-randomized studies of exposures: A users’ guide to its application in the context of GRADE. Environ Int. 2019;122:168–184. 10.1016/j.envint.2018.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Spickard A 3rd, Corbett EC Jr, Schorling JB: Improving residents' teaching skills and attitudes toward teaching. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11(8):475–480. 10.1007/BF02599042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Brukner H, Altkorn DL, Cook S, et al. : Giving effective feedback to medical students: A workshop for faculty and house staff. Med Teach. 1999;21(2):161–165. 10.1080/01421599979798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Akram A, Xin LDL, Micheál N, et al. : A systematic review of effective quality feedback measurement tools used in clinical skills assessment.2022. 10.5281/zenodo.6003404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]