INTRODUCTION

In the United States (US), more than 100,000 deaths annually are linked with adverse social determinants of health (SDoH), many of which are preventable with access to supportive resources.1 SDoH are the economic, political, and environmental systems that affect a person’s capacity to live a healthy life.2 Key SDoH include socioeconomic status, education, neighborhood and physical environment, employment, social support networks, and access to health care. Differences in individual, family, and neighborhood SDoH are primary drivers of health disparities among US children and are exacerbated by inequitable distribution of societal resources, and discriminatory and exclusionary public policies.3–5 Racial and ethnic minority groups have been especially affected by these inequities. Black children have higher death rates than White children across all age groups; in fact, all minority US children, including Black, Latino, Asian, Pacific Islander, American Indian, have worse health indices compared with their White peers.5–7 With racial and ethnic diversity among US children growing, identifying, understanding, and eliminating differential health outcomes becomes increasingly important.8

In the next 10 years, an estimated 1 million US children will require critical care services.9 Given the emerging evidence that SDoH negatively affect children across the continuum of critical illness, placing them at risk for higher illness severity, higher hospital utilization, and challenges in posthospital recovery, it is imperative that we understand and address the equity gaps in pediatric critical care and outcomes.10 To meet the standards of health care quality set forth by the National Academies of Medicine and adopted by the Agency for Healthcare Quality, the pediatric critical care community must ensure that care we deliver is equitable.11 In this article, we provide a rationale for universal SDoH screening and resource provision in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) as a key first step to the implementation of a clinical and research agenda to understand and mitigate health disparities affecting critically ill children. Our objectives therefore are 2-fold: (1) summarize SDoH impact on pediatric critical illness and outcomes to provide justification for routine screening and resource provision and (2) highlight important practical aspects of social screening that should be considered before implementation in the PICU setting.

IMPACT OF SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH ON PEDIATRIC CRITICAL ILLNESS

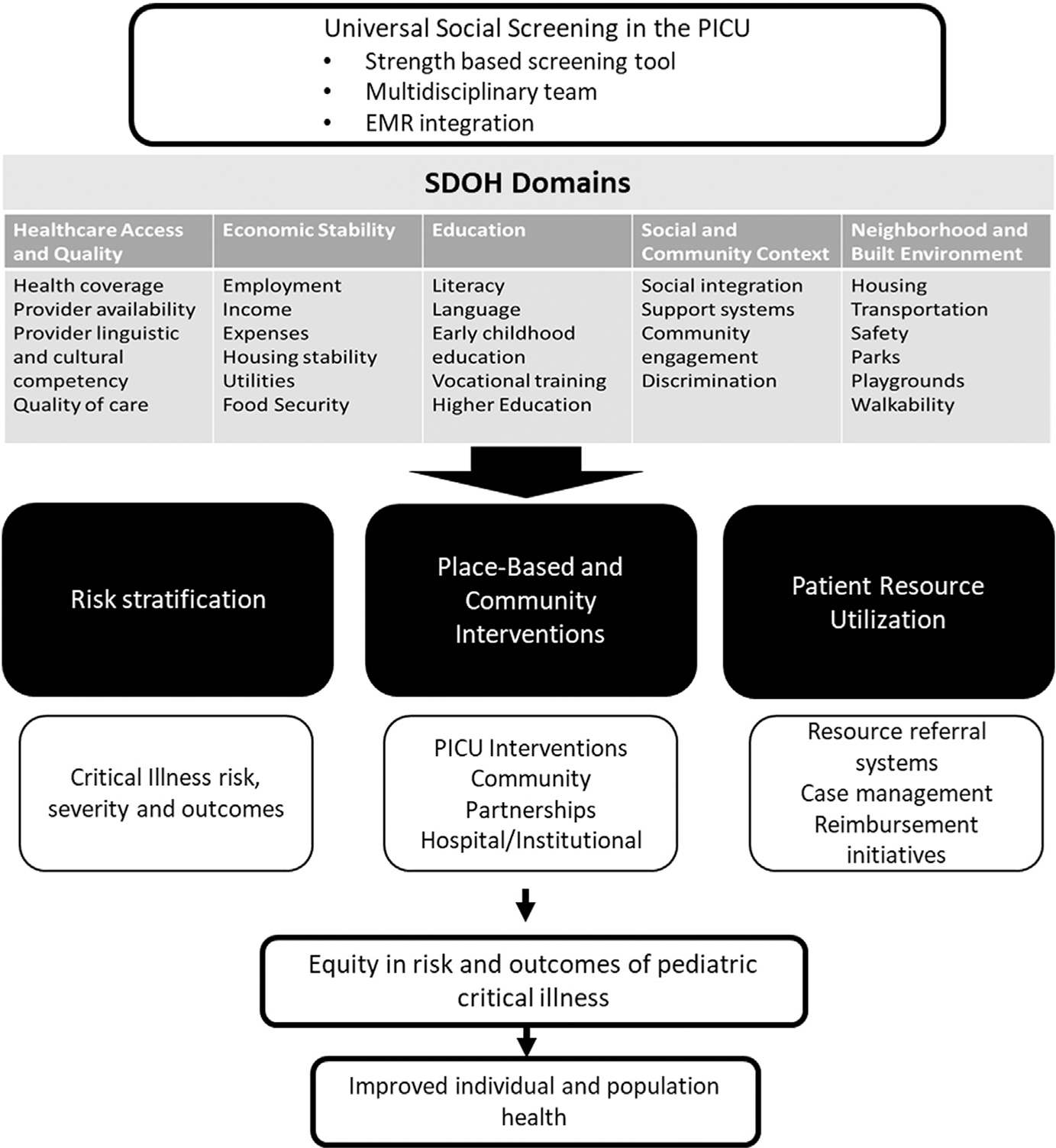

SDoH affect people throughout the life course through varied, complex, and interrelated mechanisms, and their influence on health make routine screening in both the outpatient and inpatient settings imperative. Multicenter PICU database studies show that Hispanic, Black, publicly insured, and low-income children have higher illness severity, rates of PICU admission, in-hospital mortality, readmission rates, and poorer functional outcomes than children who are White, commercially insured, or come from higher-income families.10,12–17 Routine screening and associated data collection can contribute to our mechanistic understanding of how SDoH influence pediatric critical illness. SDoH are categorized by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention into 5 domains: economic stability, community and built environment, education access and quality, health care access and quality, and social and community context (Fig. 1).18 Below is a brief summary of what is currently known about the relationship between these SDoH domains and pediatric critical illness and injury.

Fig. 1.

Impact of universal social screening on risk and outcomes of critical illness in children. (SDOH Domains adapted from Artiga S and Hinton E. Beyond Health Care: The Role of Social Determinants in Promoting Health and Health Equity. Kaiser Family Foundation via https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/beyond-health-care-the-role-of-social-determinants-in-promoting-health-and-health-equity/. Accessed November 2015; with permission.)

Health Care Access and Quality

This domain includes factors that influence a person’s access to health care, an individual’s health literacy, and existence of differential health-care quality based on social factors, including race or ethnicity. The evidence for inequality in the American healthcare system is overwhelming and sobering. Among high-income countries, the US ranks among the lowest in objective measures of health-care access.19 Low health literacy, defined as difficulties in understanding and navigating the health-care system, may affect half of all US adults.20 The National Academies of Medicine landmark publication Unequal Treatment describes pervasive differences in health-care quality between White and minority race populations.21 Socioeconomic and racial differences in rates of health insurance and access to preventive care, subspecialty care (including critical care), and pharmacy resources may place children, especially those with chronic health-care needs, at higher risk for critical illness and associated high hospital utilization.22–25 Disturbingly, race-based differences in in-hospital and surgical-related mortality exist.26–28 Single-center PICU studies suggest that publicly insured families and families of minority race or ethnicity experience differential care compared with White and privately insured families. This includes more instances of failed communication, higher rate of conflicts with the health care team, and higher rates of discrimination.29–32

Economic Stability

Economic stability has a profound influence on health due to its direct relationship with basic human needs. This domain includes poverty, employment, food security, and housing stability. Income inequality is closely linked to health inequality, and the US has one of the highest child poverty rates among all developed nations.33 Observational studies suggest low-income children are at higher risk for adverse outcomes related to critical illness including in-hospital mortality, longer hospital lengths of stay, and more frequent hospital readmissions.12,34 All poverty-related SDoH can be considered adverse childhood exposures, which predisposes a child to toxic stress. The eco-bio-developmental model of childhood health posits that repeated exposures to toxic stress can alter immune/inflammatory responses, providing a potential mechanistic explanation for the unfavorable hospital outcomes frequently observed in low-income children.35 Household poverty is also associated with substandard living conditions and lower use of preventative care, which may predispose children to higher risk of critical disease and higher severity of illness on presentation.12,14 Low-income families are also overburdened by out-of-pocket expenses related to their child’s hospitalization and required follow-up care.36 In addition, children and their families may also experience financial effects after critical illness, including inability of caregivers to return to work, which could hinder recovery and potentiate post-PICU morbidity.37

Community and Built Environment

There is increasing evidence that where one lives affects health status, quality of life, and even life expectancy.38 In addition to child-level and family-level SDoH, the neighborhood context also contributes to disparities in a child’s risk of illness, hospital course, and recovery. Availability of public transportation, pharmacies and doctors, employment and educational opportunities, healthy foods, green space, and exposure to violence, crime, and pollutants are neighborhood factors potentially placing children at risk for higher severity of illness and need for intensive care services.39,40 Disadvantaged neighborhoods may lack resources needed to make the physical and built environment conducive for optimal health. This situation leaves families underequipped to support children recovering from critical illness or children with chronic health issues, thus increasing their risk for acute exacerbations and acute care use. Furthermore, neighborhood measures of relative socioeconomic disadvantage have been linked to worse PICU outcomes, such as longer length of stay, increased need for mechanical ventilation, and increased mortality.12,34,41 Higher PICU admission rates and severity of illness scores have been observed in neighborhoods with higher rates of persons living in poverty.14 Children residing in lower socioeconomic areas seem to be at higher risk of critical illness and traumatic injury, and Black children residing in these areas have lower rates of bystander out-of-hospital resuscitation for cardiac arrests, compared with children living in more socioeconomically advantaged areas.10,42 Neighborhoods with high rates of PICU readmissions for asthma have high social vulnerability, and higher exposure to environmental toxins such as industrial pollutants, airborne microparticles, and higher ozone concentrations.43 Understanding the resources and limitations of the child’s neighborhood may inform discharge planning to reduce the risk of adverse outcomes and readmission following an episode of critical illness.

Education Access and Quality

This domain includes access to early childhood education, overall educational attainment, and literacy.18 There is strong evidence linking education and health; increasing educational attainment is associated with healthier behaviors, longer life expectancy, and overall well-being throughout the life course.44,45 In resource-limited countries, higher maternal education is linked to lower child mortality but the association between parental education and risk of severe illness and death, outside the neonatal period, among US children is not well described.46–48 Additionally, a severe illness or injury during childhood may have a profound influence on cognitive outcomes and school performance, and this relationship may be exacerbated by SDoH.49 As educational attainment is linked to long-term health outcomes, income stability, and wealth generation, preventing and responding to disparities in educational outcomes is crucially important for child survivors of critical illness.50

Social and Community Context

Studies routinely demonstrate a protective effect of social support, social cohesion, and community engagement on overall health and well-being.51,52 Accordingly, increasing community and social support is a major objective of the Healthy People 2030 initiative.53 There are limited studies on the relationship between community and social context and the risk and outcomes of critical illness in children, in part due to challenges in operationalizing the definition of “social outcome.”54

SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH SCREENING IN THE PEDIATRIC INTENSIVE CARE UNIT

To date, there are no studies directly linking routine social risk screening to improved health outcomes in hospitalized children. In the outpatient setting, 2 randomized studies conducted in primary care clinics associated implementation of social risk screening with improved child health, operationalized as a decrease in documented medical abuse and neglect in one study, and an improvement in parent-reported child health in another study.55,56 Despite lack of empiric evidence, routine screening is universally endorsed by professional societies and federal agencies, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services recently issued guidance to state Medicaid directors to encourage universal screening as part of an overall shift from fee-for-service reimbursement models to value-based care.57 These organizations recognize that investment in social health has the potential to improve individual and population-level health and lead to significant cost savings to the health care sector.58 We believe that routine, standardized screening for the SDoH is imperative for identification and mitigation of health disparities among children admitted to the PICU. We think that social screening, as part of a larger effort to achieve pediatric health equity, has the potential to improve the health of individuals and populations, and is required if we are to successfully provide just, ethical, and equitable care for critically ill children.

Screening for Social Determinants of Health May Improve the Health of Individuals

There are several potential benefits to families if routine social risk screening is implemented in an intensive care setting. First, family-centered care requires effective patient–provider communication, cultural humility and competence, acknowledgment of implicit biases, knowledge of health literacy, and an understanding of a family’s lived experiences, cultural and religious beliefs, and goals of care—all of which can be facilitated by routine screening for SDoH.59,60 Second, understanding if families struggle with food security, housing stability, adequate health-care access, and fragile support systems can allow PICU providers to contextualize a family’s ability to navigate their child’s hospitalization.61 Third, for families with identified needs, social resources that may be available within the health-care system can be mobilized.62 Fourth, the PICU encounter offers an opportunity to identify social needs in children previously not screened by their primary care providers. Although most pediatricians acknowledge its importance, few screen.63 Finally, screening can identify family and community factors that could help or hinder recovery after critical illness. Up to 70% of children develop a new morbidity following the PICU stay, and it is increasingly recognized that the development of postintensive care syndrome is related to both illness factors and the social milieu, including SDoH.64,65 In-depth assessments of family social needs during the acute phase of critical illness are necessary for provision of optimal anticipatory guidance to families in preparation for recovery after critical illness.

Screening for Social Determinants of Health May Improve the Health of Populations

Section 4302 (Understanding Health Disparities: Data Collection and Analysis) of the Affordable Care Act outlines minimum data-collection standards for race, ethnicity, sex, language, and disabilities for all Department of Health and Human Services programs and surveys.66 The Institute for Healthcare Improvement and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality have independently stated systematic collection of the aforementioned demographic data, as well as universal screening for SDoH, is necessary for identification, understanding, and elimination of the root causes of health disparities.67–69 As part of local and multicenter collaborative patient safety initiatives, PICUs routinely perform quality improvement projects that rely on accurate data collection for stratification and dissemination of quality performance. Examples of improvement targets include health-care–acquired conditions, patient handoffs, antibiotic and blood culture stewardship, and pediatric severe sepsis.70–73 To date, there are no large-scale databases with SDoH data for critically ill children, which could inform health equity projects.74 The Virtual Pediatric Systems (VPS, LLC http://www.myvps.org/) database includes more than 1 million PICU admissions from more than 130 centers and was developed to improve PICU care delivery through quality improvement and research initiatives.75 The Pediatric Health Information System (Children’s Hospital Association, Lenexa, KS) is an administrative database including resource utilization data from more than 45 tertiary centers associated with the Children’s Hospital Association. Both datasets were designed, in part, to drive health care improvement through benchmarking, quality improvement, and research initiatives, although arguably they currently lack the data necessary to fully identify inequitable health-care delivery.75,76 For example, race and ethnicity was not a “mandatory” data field in VPS until 2021, and neither registry collects data on family-level social determinants.

Collection of demographic and social determinant data should be standardized, and when possible, captured in institutional electronic health records (EHRs) and multiinstitutional research and administrative databases. This would allow PICUs to stratify outcome data, including mortality, length of stay, hospital-acquired conditions, and readmissions-a necessary first step in the effort to achieve health equity. Social screening can promote better understanding of the unique needs of the PICU patient population, and spur hospital-wide initiatives aimed to improve population health, such as financial navigation programs77 for medical-related financial stress, hospital-based food pantries,62 and housing interventions78 for food and housing insecurity. Finally, adding a social risk “score” alongside an index of mortality or illness severity score (eg, pediatric logistic organ dysfunction-2 [PELOD-2] score) could highlight those patients who may have a more difficult PICU course, or those who will be at higher risk for mortality or require intensive post-PICU follow-up to optimize chances for good health outcomes. Furthermore, there is a critical need for empirical research on SDoH screening in the PICU, and implemented interventions aimed at reducing identified inequalities or disparities. Any research program, however, must collect and report on race and ethnicity, recognizing these labels as social constructs. Data must be collected with adequate rigor to allow sufficient evaluation of race and ethnicity as contributors to the research outcomes of interest, within a racial equity framework.79

As evidence builds for place-based disparities in risk of pediatric critical illness, collecting neighborhood-level data can facilitate identification of “hot spots” amenable to public health interventions collaboratively developed by health systems, communities, and governments.80 The influence of neighborhood on child health is complex, with research revealing multiple, distinct, but overlapping relationships between a child’s environment and its health. For example, unfavorable asthma outcomes have independently been linked to poor housing quality, high levels of air pollution, challenges in access to preventative care and pharmacies, and lack of transportation.81 Identifying communities conferring high levels of risk with composite markers of neighborhood health, such as the publicly available Child Opportunity Index, could allow researchers to measure associations between multidimensional, interrelated neighborhood characteristics and health outcomes.82 The Breathe Easy at Home program in Boston and the Collaboration to Lessen Environmental Asthma Risks at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital are examples of neighborhood-based programs through which disparities in asthma outcomes were identified and mitigated through health system-community collaborations.83,84 Furthermore, incorporating composite neighborhood risk scores into the EHR could facilitate a deeper understanding of disease risk and challenges with recovery, allowing clinicians the opportunity to tailor their anticipatory guidance and therapeutic choices for individual patients, and support the development of relationships with community partnerships to affect population health outcomes.81

Screening in an Acute Care Setting

In the last decade, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has recognized the importance of poverty and related social determinants to child health and wellbeing by releasing 4 policy statements.85–88 Although most pediatricians think that routine screening for social needs is important, few think that implementation is feasible.89 In outpatient clinics, time constraints, lack of staff and referral resources, workflow disruptions, and inadequate reimbursement policies contribute to overall low rates of screening.90 Subspecialty pediatricians and hospital-based pediatricians report similar barriers to screening.90,91 Although the AAP makes no specific recommendations surrounding SDoH screening in the acute care setting, in developing an interdisciplinary approach to mitigating social risk, the Academy emphasizes the benefits of the medical home, medical-legal partnerships, health system-community partnerships, and care coordination, all of which can—and should—be facilitated by hospital-based care teams.85 A PICU admission offers a unique opportunity for SDoH screening; however, to our knowledge, no implementation framework or validated tool exists for SDoH screening in the PICU.92 High staff-to-patient ratios, parent and guardian presence, and the availability of social workers and case workers at many tertiary care PICUs make screening for SDoH and resource referral potentially feasible. When planning the implementation of SDoH screening and data collection, the following should be considered:

Educate providers on the impact of SDoH and the relevance of screening. All staff members involved in the direct care of PICU patients should be educated on influences SDoH have on the continuum of critical illness and the influence of screening, with the goal of improving their understanding of the structures, practices, policies and processes that contribute to health inequities, and the importance of addressing unmet social needs of patients and their families.

All families should undergo screening. Universal screening, as part of the intake process, will minimize a family from feeling targeted, identify needs in families who may otherwise not ask for help if not screened, allows staff members to gain expertise in screening through repetition, and provides an accurate population-based picture of the social needs of the PICU population.

Employ a strength-based approach. Each family has unique strengths, and most thrive despite adversity. These strengths should be recognized and celebrated through strength-based screening, which provides families with opportunities and experiences to build their protective factors, such as parental resilience and social support.93 This approach will improve participation and engagement of patients and families.94 Providers should avoid screening approaches that may create a sense of shame, or that place blame for structural socio-economic conditions outside of families’ control.93,94

Staff should be trained to screen. Families may be reticent to answer sensitive questions, and those who conduct social needs screening with families must be trained and/or have experience in the core competencies of trauma-informed and culturally effective care.93

SDoH needs identified from screening should be paired with appropriate referrals and resources. SDoH screening followed by linkage to appropriate resources within the hospital and/or community has been associated with improved child health outcomes.55 Hospitals have successfully partnered with community organizations to establish food pantries, offer transportation resources, and provide housing vouchers to families in need. A compendium of local and national resources, such as the United Way’s national 2–1-195 program, can be created and made readily available to share with families in need.

Build upon existing systems. To successfully implement widespread screening and intervention processes across PICUs, it will be important to leverage existing systems and ensure collaboration occur across multidisciplinary teams, both within and across institutions. Integrating SDoH screening tools into the EHR available to different care providers at transition points in a patient’s care will facilitate resource provision and rapid analysis of social risk as a factor that may directly or indirectly affect the patient’s critical care trajectory and can also prevent families from undergoing repeated screening within the same institution.95 Consideration should be made for EHR documentation of identified social needs, using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision “miscellaneous Z codes” for the purposes of case management and follow-up, risk-adjustment modeling, and for inclusion in future reimbursement initiatives.96–98

Develop valid and reliable screening tools. Few screening tools currently used in pediatric practice have undergone validity and reliability testing.99 Ensuring the tools are accurate and inform care for intended patient populations should be a priority area of research in this area.

Screening for the Social Determinants of Health is Required for Just and Equitable Health Care

As a group, critical care clinicians provide ethically sound care and are well-versed in maximizing patient good (beneficence) and minimizing patient harm (nonmaleficence). Ethical health-care delivery must also incorporate principles of justice that affect individual-level and population-level care. As a core principle of biomedical ethics, achieving justice in health care requires that (1) individuals have an equal right to basic needs and liberties and (2) when resources are limited, decisions related to resource distribution ensure those individuals with the greatest need are benefited, and all individuals have equal opportunity to obtain resources.100 Addressing health-related social risks through SDoH screening can ensure that basic health needs are met, whereas assessing for and responding to structural barriers or systemic inequities will promote justice.

Identification of structural barriers to health may uncover social needs that we are unable to provide immediate resources for thus creating moral dilemma for both health-care providers and patients. However, building a narrative for resources or policy changes to address these concerns is critical to ultimately reducing their impact. Collaborating with medical legal partnerships can be an effective mechanism both to address individual and systemic level social risks through advocacy-recent research suggests that this collaborative approach can lead to improved health outcomes.101

SUMMARY

Disparities in the risk, care, and outcomes of critical illness in children are prevalent and unacceptable. Widespread implementation of SDoH screening in our PICUs is an important first step in addressing the causes of these disparities. Beyond increasing our understanding of the mechanisms that potentiate disparities, SDoH screening will facilitate identification of vulnerable families and children likely to benefit from linkage to resources within the hospital and community. Furthermore, information gathered through screening will enable the development of effective interventions and policies aimed at ensuring distribution of resources to those with the greatest need—a core element of just and equitable health care.

KEY POINTS.

SDoH impact children along the continuum of critical illness, making screening an important first step in improving clinical care delivery through quality improvement and research initiatives.

A child’s admission to a PICU offers a unique opportunity for social screening. High staff to patient ratios, parent presence, and availability of social workers at tertiary centers can make screening feasible.

Widespread implementation of SDoH screening across PICUs has the potential to increase our understanding of mechanisms that potentiate health disparities, facilitate linkage of vulnerable families to social resources, and enable development of public health interventions.

CLINICS CARE POINTS.

Multicenter cohort studies have demonstrated the existence of disparities in illness severity, rates of PICU admission, in-hospital mortality, readmission rates, and long-term functional outcomes based on race, ethnicity, insurance status, and socioeconomic status.

Implementation of universal SDoH screening in a PICU should include appropriate staff training, employ a strengths-based approach, and be paired with appropriate hospital-based and community-based resource referral.

Development of a valid and reliable screening tools for use in the PICU setting should be a priority of future research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Dr. Talati Paquette’s work is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (1K23HD098289)

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Galea S, Tracy M, Hoggatt KJ, et al. Estimated deaths attributable to social factors in the United States. Am J Public Health 2011;101(8):1456–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Social determinants of health. 2018. Available at: http://www.who.int/social_determinants/en/. Accessed May 30, 2022.

- 3.Braveman P, Egerter S, Williams DR. The social determinants of health: coming of age. Annu Rev Public Health 2011;32:381–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health: it’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep 2014;129(Suppl 2):19–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flores G, Committee On Pediatric R. Technical report–racial and ethnic disparities in the health and health care of children. Pediatrics 2010;125(4):e979–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howell E, Decker S, Hogan S, et al. Declining child mortality and continuing racial disparities in the era of the Medicaid and SCHIP insurance coverage expansions. Am J Public Health 2010;100(12):2500–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oberg C, Colianni S, King-Schultz L. Child health disparities in the 21st century. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 2016;46(9):291–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.U.S. child population decreasing, becoming more diverse. [press release; ]. November 1, 2021. Available at: https://publications.aap.org/aapnews/news/17443. Accessed June 13th, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garber N, Watson RS, Linde-Zwirble WT. The size and scope of intensive care for children in the US. Crit Care Med 2003;31(Suppl):A78. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitchell HK, Reddy A, Perry MA, et al. Racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in paediatric critical care in the USA. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2021;5(10):739–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Records CotRSaBDaMfEH. Capturing social and behavioral domains and measures in electronic health records: phase 2. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andrist E, Riley CL, Brokamp C, et al. Neighborhood poverty and pediatric intensive care use. Pediatrics 2019;144(6):e20190748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Czaja AS, Zimmerman JJ, Nathens AB. Readmission and late mortality after pediatric severe sepsis. Pediatrics 2009;123(3):849–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Epstein D, Reibel M, Unger JB, et al. The effect of neighborhood and individual characteristics on pediatric critical illness. J Community Health 2014;39(4):753–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turner D, Simpson P, Li SH, et al. Racial disparities in pediatric intensive care unit admissions. Southampt Med J 2011;104(9):640–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lopez AM, Tilford JM, Anand KJ, et al. Variation in pediatric intensive care therapies and outcomes by race, gender, and insurance status. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2006;7(1):2–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Epstein D, Wong CF, Khemani RG, et al. Race/Ethnicity is not associated with mortality in the PICU. Pediatrics 2011;127(3):e588–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prevention CfDCa. About social determinants of health. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/socialdeterminants/about.html. Accessed June 6, 2022.

- 19.Weaver MR, Nandakumar V, Joffe J, et al. Variation in health care access and quality among US states and high-income countries with universal health insurance coverage. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4(6):e2114730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Health Literacy. Health Literacy. In: Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA, editors. A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25009856/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities. In: Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown LE, Franca UL, McManus ML. Socioeconomic disadvantage and distance to pediatric critical care. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2021;22(12):1033–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guagliardo MF, Ronzio CR, Cheung I, et al. Physician accessibility: an urban case study of pediatric providers. Health Place 2004;10(3):273–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi L, Stevens GD. Disparities in access to care and satisfaction among U.S. children: the roles of race/ethnicity and poverty status. Public Health Rep 2005;120(4):431–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flores G, Tomany-Korman SC. Racial and ethnic disparities in medical and dental health, access to care, and use of services in US children. Pediatrics 2008;121(2):e286–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Castellanos MI, Dongarwar D, Wanser R, et al. In-hospital mortality and racial disparity in children and adolescents with acute myeloid leukemia: a population-based study. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2022;44(1):e114–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitchell HK, Reddy A, Montoya-Williams D, et al. Hospital outcomes for children with severe sepsis in the USA by race or ethnicity and insurance status: a population-based, retrospective cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2021;5(2):103–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Willer BL, Mpody C, Tobias JD, et al. Association of race and family socioeconomic status with pediatric postoperative mortality. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5(3):e222989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeLemos D, Chen M, Romer A, et al. Building trust through communication in the intensive care unit: HICCC. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2010;11(3):378–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Studdert DM, Burns JP, Mello MM, et al. Nature of conflict in the care of pediatric intensive care patients with prolonged stay. Pediatrics 2003;112(3 Pt 1):553–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zurca AD, Wang J, Cheng YI, et al. Racial minority families’ preferences for communication in pediatric intensive care often overlooked. J Natl Med Assoc 2020;112(1):74–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Epstein D, Unger JB, Ornelas B, et al. Satisfaction with care and decision making among parents/caregivers in the pediatric intensive care unit: a comparison between English-speaking whites and Latinos. J Crit Care 2015;30(2):236–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bor J, Cohen GH, Galea S. Population health in an era of rising income inequality: USA, 1980–2015. Lancet 2017;389(10077):1475–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Slain KN, Shein SL, Stormorken AG, et al. Outcomes of children with critical bronchiolitis living in poor communities. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2018;57(9):1027–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shonkoff JP, Garner AS, Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of C, et al. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics 2012;129(1):e232–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clark ME, Cummings BM, Kuhlthau K, et al. Impact of pediatric intensive care unit admission on family financial status and productivity: a pilot study. J Intensive Care Med 2019;34(11–12):973–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kamdar BB, Sepulveda KA, Chong A, et al. Return to work and lost earnings after acute respiratory distress syndrome: a 5-year prospective, longitudinal study of long-term survivors. Thorax 2018;73(2):125–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prochaska JD, Jupiter DC, Horel S, et al. Rural-urban differences in estimated life expectancy associated with neighborhood-level cumulative social and environmental determinants. Prev Med 2020;139:106214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kirby JB, Kaneda T. Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and access to health care. J Health Soc Behav 2005;46(1):15–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wooldridge G, Murthy S. Pediatric critical care and the climate emergency: our responsibilities and a call for change. Front Pediatr 2020;8:472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Colvin JD, Zaniletti I, Fieldston ES, et al. Socioeconomic status and in-hospital pediatric mortality. Pediatrics 2013;131(1):e182–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Naim MY, Griffis HM, Burke RV, et al. Race/ethnicity and neighborhood characteristics are associated with bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation in pediatric out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in the United States: a study from CARES. J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8(14):e012637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grunwell JR, Opolka C, Mason C, et al. Geospatial analysis of social determinants of health identifies neighborhood hot spots associated with pediatric intensive care use for life-threatening asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2022;10(4):981–991 e981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.The Lancet Public H. Education: a neglected social determinant of health. Lancet Public Health 2020;5(7):e361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Assari S, Caldwell CH, Bazargan M. Association between parental educational attainment and youth outcomes and role of race/ethnicity. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2(11):e1916018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Makate M, Makate C. The causal effect of increased primary schooling on child mortality in Malawi: universal primary education as a natural experiment. Soc Sci Med 2016;168:72–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Andriano L, Monden CWS. The causal effect of maternal education on child mortality: evidence from a quasi-experiment in Malawi and Uganda. Demography 2019;56(5):1765–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gage TB, Fang F, O’Neill E, et al. Maternal education, birth weight, and infant mortality in the United States. Demography 2013;50(2):615–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tomaszewski W, Ablaza C, Straney L, et al. Educational outcomes of childhood survivors of critical illness-A population-based linkage study. Crit Care Med 2022;50(6):901–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hahn RA, Truman BI. Education improves public health and promotes health equity. Int J Health Serv 2015;45(4):657–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reblin M, Uchino BN. Social and emotional support and its implication for health. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2008;21(2):201–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Singh R, Javed Z, Yahya T, et al. Community and social context: an important social determinant of cardiovascular disease. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J 2021;17(4):15–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Healthy People 2030: Social Determinants of Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health. Accessed June 17th, 2022.

- 54.Daughtrey H, Slain KN, Derrington S, et al. , POST-PICU and PICU-COS Investigators of the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI) and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Networks (CPCCRN). Measuring social health following pediatric critical illness: a scoping review and conceptual framework. J Intensive Care Med 2022. 10.1177/08850666221102815. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gottlieb LM, Hessler D, Long D, et al. Effects of social needs screening and in-person service navigation on child health: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr 2016;170(11):e162521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dubowitz H, Feigelman S, Lane W, et al. Pediatric primary care to help prevent child maltreatment: the Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK) Model. Pediatrics 2009;123(3):858–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services. State Health Official # 21–001. (2021). RE: Opportunities in medicaid and CHIP to address social determinants of health (SDOH). https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/sho21001.pdf. Accessed June 12, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lipson DJ. Medicaid’s Role in improving the social determinants of health: opportunities for states, 14, 201 7. Available at: https://www.nasi.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Opportunities-for-States_web.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2022.

- 59.Perez-Stable EJ, El-Toukhy S. Communicating with diverse patients: how patient and clinician factors affect disparities. Patient Educ Couns 2018;101(12):2186–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Greene-Moton E, Minkler M. Cultural competence or cultural humility? Moving beyond the debate. Health Promot Pract 2020;21(1):142–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kangovi S, Barg FK, Carter T, et al. Challenges faced by patients with low socioeconomic status during the post-hospital transition. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29(2):283–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gany F, Lee T, Loeb R, et al. Use of hospital-based food pantries among low-income urban cancer patients. J Community Health 2015;40(6):1193–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fleegler EW, Lieu TA, Wise PH, et al. Families’ health-related social problems and missed referral opportunities. Pediatrics 2007;119(6):e1332–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Watson RS, Choong K, Colville G, et al. Life after critical illness in children-toward an understanding of pediatric post-intensive care syndrome. J Pediatr 2018;198:16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kachmar AG, Watson RS, Wypij D, et al. Randomized evaluation of sedation titration for respiratory failure investigative T. Association of socioeconomic status with postdischarge pediatric resource use and quality of life. Crit Care Med 2022;50(2):e117–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dorsey R, Graham G, Glied S, et al. Implementing health reform: improved data collection and the monitoring of health disparities. Annu Rev Public Health 2014;35:123–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wyatt RLM, Botwinick L, Mate K, et al. Achieving health equity: a guide for health care organizations. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Forum NQ. A roadmap for promoting health equity and eliminating disparities. Washington (DC): The Four I’s for Health Equity; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 69.O’Kane M ea. An equity agenda for the field of health care quality improvement. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine; 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Miller MR, Niedner MF, Huskins WC, et al. Reducing PICU central line-associated bloodstream infections: 3-year results. Pediatrics 2011;128(5):e1077–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Malenka EC, Nett ST, Fussell M, et al. Improving handoffs between operating room and pediatric intensive care teams: before and after study. Pediatr Qual Saf 2018;3(5):e101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Larsen GY, Brilli R, Macias CG, et al. Development of a quality improvement learning collaborative to improve pediatric sepsis outcomes. Pediatrics 2021;147(1):e20201434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Woods-Hill CZ, Colantuoni EA, Koontz DW, et al. Association of diagnostic stewardship for blood cultures in critically ill children with culture rates, antibiotic use, and patient outcomes: results of the bright STAR collaborative. JAMA Pediatr 2022;176(7):690–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Riley C, Maxwell A, Parsons A, et al. Disease prevention & health promotion: what’s critical care got to do with it? Transl Pediatr 2018;7(4):262–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wetzel RC. Pediatric intensive care databases for quality improvement. J Pediatr Intensive Care 2016;5(3):81–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kittle K, Currier K, Dyk L, et al. Using a pediatric database to drive quality improvement. Semin Pediatr Surg 2002;11(1):60–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Watabayashi K, Steelquist J, Overstreet KA, et al. A pilot study of a comprehensive financial navigation program in patients with cancer and caregivers. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2020;18(10):1366–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kelly A, Fazio D, Padgett D, et al. Patient views on emergency department screening and interventions related to housing. Acad Emerg Med 2022;29(5):589–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zurca AD, Suttle ML, October TW. An antiracism approach to conducting, reporting, and evaluating pediatric critical care research. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2022;23(2):129–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Beck AF, Anderson KL, Rich K, et al. Cooling the hot spots where child hospitalization rates are high: a neighborhood approach to population health. Health Aff (Millwood) 2019;38(9):1433–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Beck AF, Sandel MT, Ryan PH, et al. Mapping neighborhood health geomarkers to clinical care decisions to promote equity in child health. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36(6):999–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Krager MK, Puls HT, Bettenhausen JL, et al. The child opportunity index 2.0 and hospitalizations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions. Pediatrics 2021;148(2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Beck AF, Simmons JM, Sauers HS, et al. Connecting at-risk inpatient asthmatics to a community-based program to reduce home environmental risks: care system redesign using quality improvement methods. Hosp Pediatr 2013;3(4):326–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rosofsky A, Reid M, Sandel M, et al. Breathe easy at home: a qualitative evaluation of a pediatric asthma intervention. Glob Qual Nurs Res 2016;3. 2333393616676154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.COUNCIL ON COMMUNITY PEDIATRICS. Poverty and child health in the United States. Pediatrics 2016;137(4):e20160339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pascoe JM, Wood DL, Duffee JH, et al. , COMMITTEE ON PSYCHOSOCIAL ASPECTS OF CHILD AND FAMILY HEALTH, COUNCIL ON COMMUNITY PEDIATRICS.. Mediators and adverse effects of child poverty in the United States. Pediatrics 2016;137(4):e20160340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.COUNCIL ON COMMUNITY PEDIATRICS, COMMITTEE ON NUTRITION.. Promoting food security for all children. Pediatrics 2015;136(5):e1431–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.COUNCIL ON COMMUNITY PEDIATRICS. Providing care for children and adolescents facing homelessness and housing insecurity. Pediatrics 2013;131(6):1206–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Garg A, Cull W, Olson L, et al. Screening and referral for low-income families’ social determinants of health by US pediatricians. Acad Pediatr 2019;19(8):875–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schwartz B, Herrmann LE, Librizzi J, et al. Screening for social determinants of health in hospitalized children. Hosp Pediatr 2020;10(1):29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lax Y, Bathory E, Braganza S. Pediatric primary care and subspecialist providers’ comfort, attitudes and practices screening and referring for social determinants of health. BMC Health Serv Res 2021;21(1):956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.La Count S, McClusky C, Morrow SE, et al. Food insecurity in families with critically ill children: a single-center observational study in pittsburgh. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2021;22(4):e275–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Flacks J and Boynton-Jarrett RF, A Strengths-based Approaches to Screening Families for Health-Related Social Needs in the Healthcare Setting. The Center for the Study of Social Policy. Washington, DC, 2018. https://www.ctc-ri.org/sites/default/files/uploads/A-strengths-based-approach-to-screening.pdf. Accessed May 23, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Frankowski BL, Leader IC, Duncan PM. Strength-based interviewing. Adolesc Med State Art Rev 2009;20(1):22–40, vii-viii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lindau ST. CommunityRx, an E-prescribing system connecting people to community resources. Am J Public Health 2019;109(4):546–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Clark MA, Gurewich D. Integrating measures of social determinants of health into health care encounters: opportunities and challenges. Med Care 2017;55(9):807–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Torres JM, Lawlor J, Colvin JD, et al. ICD social codes: an underutilized resource for tracking social needs. Med Care 2017;55(9):810–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Weeks WB, Cao SY, Lester CM, et al. Use of Z-codes to record social determinants of health among fee-for-service medicare beneficiaries in 2017. J Gen Intern Med 2020;35(3):952–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sokol R, Austin A, Chandler C, et al. Screening children for social determinants of health: a systematic review. Pediatrics 2019;144(4):e20191622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Political JR. Liberalism. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Beck AF, Henize AW, Qiu T, et al. Reductions in hospitalizations among children referred to a primary care-based medical-legal partnership. Health Aff (Millwood) 2022;41(3):341–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]