ABSTRACT

Zoonotic coronaviruses (CoVs) caused major human outbreaks in the last two decades. One of the biggest challenges during future CoV disease is ensuring rapid detection and diagnosis at the early phase of a zoonotic event, and active surveillance to the zoonotic high-risk CoVs appears the best way at the present time to provide early warnings. However, there is neither an evaluation of spillover potential nor diagnosis tools for the majority of CoVs. Here, we analyzed the viral traits, including population, genetic diversity, receptor and host species for all 40 alpha- and beta-CoV species, where the human-infecting CoVs are from. Our analysis proposed 20 high-risk CoV species, including 6 of which jumped to human, 3 with evidence of spillover but not to human and 11 without evidence of spillover yet, which prediction were further supported by an analysis of the history of CoV zoonosis. We also found three major zoonotic sources: multiple bat-origin CoV species, the rodent-origin sub-genus Embecovirus and the CoV species AlphaCoV1. Moreover, the Rhinolophidae and Hipposideridae bats harbour a significantly higher proportion of human-threatening CoV species, whereas camel, civet, swine and pangolin could be important intermediate hosts during CoV zoonotic transmission. Finally, we established quick and sensitive serologic tools for a list of proposed high-risk CoVs and validated the methods in serum cross-reaction assays using hyper-immune rabbit sera or clinical samples. By comprehensive risk assessment of the potential human-infecting CoVs, our work provides a theoretical or practical basis for future CoV disease preparedness.

KEYWORDS: Coronavirus, spillover, zoonosis, risk assessment, bats, serology

Introduction

Emerging infectious diseases caused by coronaviruses (CoVs) pose great threats to the public health. It is almost certain that there will be future disease emergence and it is highly likely a CoV disease again [1]. Thus, the early preparation for the animal CoVs with risk of spillover is important for future disease preparedness, regarding the likely animal origin of SARS, MERS and COVID-19 [2–4]. However, there have been two major hurdles.

First, it is not known which CoV poses a higher risk of spillover. There are four CoV genus, including alpha (α), beta (β), gamma (γ) and delta (δ), and all CoVs causing human pandemics are from alpha- or beta-CoVs. According to the latest ICTV classification, there are 40 CoV species in the alpha- and beta-CoV genus, and 27/40 of the CoV species (67.5%) can be found or exclusively be found in bats (Figure 1A) [5]. Compared to the extensive study on the bat Sarbecoviruses viral species, or SARS-related CoV (SARSr-CoV), there is little knowledge on the majority of other CoVs species, which were discovered but without spillover risk analysis. Previous studies are mainly based on ecological models to predict the zoonotic hotspot viruses [6–9]. Thus, an evaluation of the spillover risk of CoVs, particularly on alpha- and beta-CoVs is urgently needed.

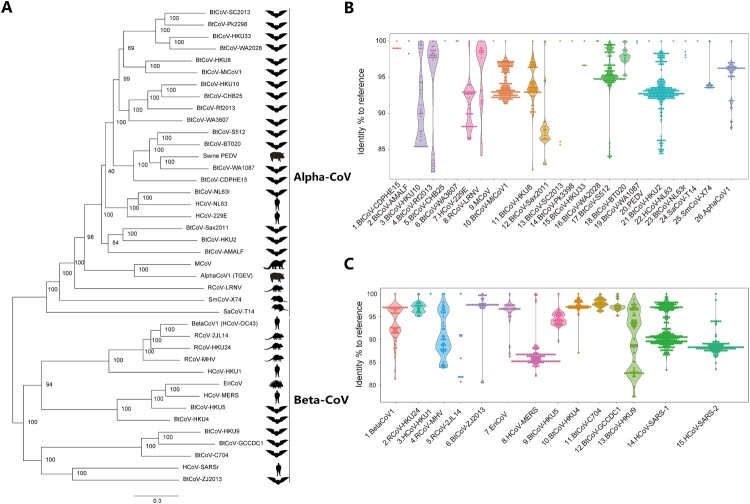

Figure 1.

Genetic diversity of alpha- and beta-CoVs. (A) A phylogeny of alpha- and beta-CoV species according to the latest ICTV classification. We uniformly named the CoVs with host species (e.g. BtCoV) plus their unique identity (e.g. SC2013). Abbreviations: BtCoV, Bat CoV; HCoV, Human CoV; RCoV, Rodent CoV; MCoV, Mink CoV; EriCoV, Erinaceus CoV (hedgehog). Notably, a human representative was used for some zoonotic viral species, includes SARS-related, MERS-related, 229E-related and OC43-related, albeit viruses can also be found in bats (SARSr, MERSr and 229Er) or other mammals (OC43). (B-C) Violin plots show the genetic diversity of each alpha (B) or beta (C) CoV species. A 440 bp RdRp sequence was collected from public database and blasted to the reference CoV sequences (Supplementary table 1). Data shown as percentage to reference, each plot represents a virus species. We matched the sequences to HCoV-SARS-1 and HCoV-SARS-2, respectively, without repeated sequence counting.

Second, it is difficult to spot the CoV emergence at an early stage. In one way, an animal CoV would likely require further adaptation to efficiently replicate in humans, and it is expected that only mild or asymptomatic signs of disease shown up in humans during early stage of zoonosis [10]. Therefore, active surveillance of spillover high-risk CoVs appears the only way to spot CoV emergence at an early stage [3]. In another way, nucleotide-based surveillance tools, such as PCR and NGS would likely be ineffective due to the narrow detection window upon disease onset. In contrast, retrospective sero-surveillance entitles a long detection window. Thus, a combination of the two methods appears suitable for this purpose.

In this study, we argue that by analyzing the viral traits, including population, genetic diversity, receptor, host species and the history of zoonosis for alpha- and beta-CoVs, we would be able to evaluate the risk of human spillover for CoVs. Correspondingly, we established quick and sensitive serologic tools for a list of high-risk CoVs. Our study provided important information and tools for future CoV diseases, which could be important candidates for Disease X that may be caused by a pathogen currently not recognized to cause human disease or a known pathogen with changed epidemiological characteristics [11].

Materials and methods

CoV phylogenetic and partial RdRp analysis

The representative Alpha and Beta coronavirus genomes were selected according to ICTV species classification and downloaded from NCBI database, and accession numbers can be found in Supplementary Table 1. All RdRp sequences under the taxonomy Coronaviridae (Taxonomy ID: txid11118) were downloaded from NCBI. The genome or RdRp were analyzed (SI Methods).

CoV zoonosis risk and zoonotic source analysis

The zoonosis risk analysis of CoVs was conducted using these standards: (1) Those have a large population and high genetic diversity. (2) By literature searching, that already infected human or those may use human receptors. These viral species may have a higher chance of generating human-infecting viruses. (3) The virus in certain viral species (e.g. alphaCoV1) or having certain characters (e.g. APN using) that enables (easier) host jumping. The host information for each virus was obtained from NCBI database. The geographical ranges of these species were according to IUCN redlist (www.iucnredlist.org).

Protein expression, antibody production and serology

In total, 14 of 16 selected CoV NP and corresponding rabbit polyclonal antibody were prepared in this study. The details of protein expression or antibody production can be found in SI Methods. The 16 selected NP were inserted into the LIPS pREN2 vector respectively. The validation of LIPS serology using either hyper-immune rabbit serum or clinical samples was conducted. A series of in-house anti-NP IgG ELISA kits were developed to validate the cross-reaction assay results obtained by LIPS (SI Methods).

Results

Population and genetic diversity of alpha- and beta-CoVs

We first did phylogenetic analysis of alpha- and beta-CoVs, as well as a host phylogeny to show the relationship between bats and non-bats (Figure 1A, Supplementary Figure 1 and Table 1). According to the latest ICTV classification [5], there are 26 alpha-CoV and 14 beta-CoVs, although the number is still expanding rapidly. It can be observed that the majority of CoV species, including 19 alpha-CoV (19/26, including HCoV-229E) and 8 beta-CoV (8/14, including HCoV-MERS and HCoV-SARSr), were found in bats or naturally harboured by bats, suggesting bats are the most important natural hosts of CoVs. Moreover, rodent, shrew, hedgehog, camel, pig or human may also harbour at least one CoV species (Figure 1A).

Next, we ought to understand the zoonotic risk of CoVs. We believe the CoV species that have a large population are more likely carried by the natural hosts for long time (which is also prone to generating genetic diversity), and the viral species that have a high genetic diversity in the natural hosts are more easily to form a quasi-species pool of viruses that capable of infecting human or other mammals. Thus, the CoV species that have a large population and high genetic diversity appears to have higher zoonotic risk. To this end, we analyzed the viral population and genetic diversity of each CoV species based on a short 440-bp conserved RdRp sequences collected from public database.

In alpha-CoVs, a prominent large population (>20) and high genetic diversity (>10%) was mainly found to bat viruses, including BtCoV-HKU10, BtCoV-Rf2013, HCoV-229E-related, BtCoV-MiCoV1, BtCoV-HKU8, BtCoV-Sax2011, BtCoV-S512 and BtCoV-HKU2 (Figure 1B and Supplementary Table 2). The only two from other species are rodent RCoV-LRNV and alphaCoV1, the latter of which was widely harboured by non-bat/rodent mammals and may cause disease to domestic animals (porcine TGEV) or humans (CCoV-huPn-2018) [12]. The rest of alpha-CoVs were either occasionally found in natural hosts or only found in dead-end host. The Pig PEDV and HCoV-NL63 were highly prevalent in their respective dead-end host but with little genetic diversity (<1%) [13]. In beta-CoVs, both bats and rodents may carry high-risk CoV species, including bat SARS-related CoV, BtCoV-HKU9, BtCoV-HKU4, BtCoV-HKU5, MERSr-CoV, BtCoV-ZJ2013 and RCoV-MHV (Figure 1C and Supplementary Table 3). Moreover, the likely rodent-origin BetaCoV1 was widely carried by a list of mammalian species (e.g. human OC43) [14]. The hedgehog EriCoV that related to MERS-CoV is the only non-bat and non-rodent viral species that should be emphasized (Figure 1A and 1C). In contrast, other beta-CoV species have shown small population or lack genetic diversity. Collectively, we believe some of the wildlife CoVs are more prone to cause future zoonosis than the others, irrespective of the sampling bias.

The zoonotic probability of alpha- and beta-CoVs

Next, by analyzing the past CoV zoonotic events, we ought to determine whether the high-risk viruses defined above are related to a higher chance of causing zoonosis. We also want to understand the virological characters, evolutionary history or natural hosts of the previous CoV disease agents, aiming to find common characters that may determine a zoonosis.

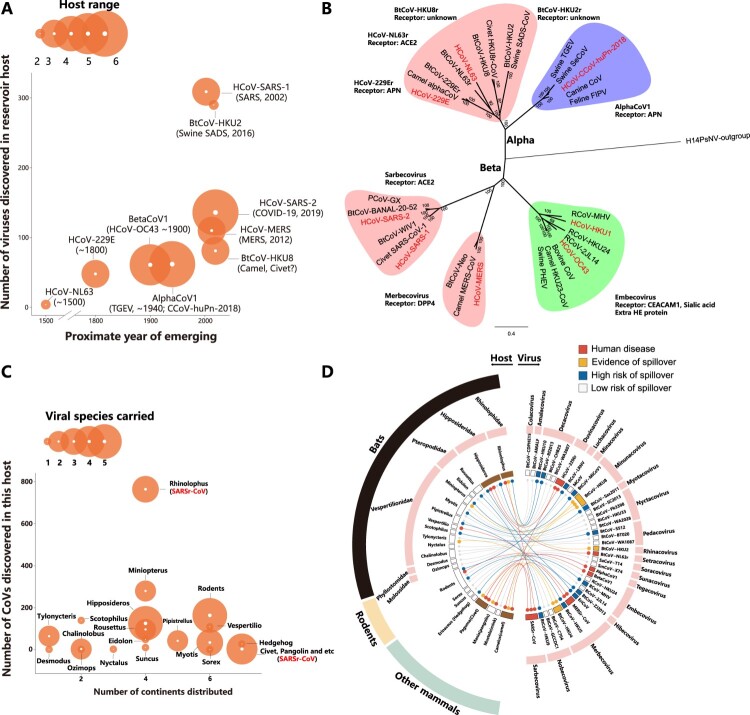

It is well known that there were eight humans CoV diseases [2,12]. In an analysis of the host range, number of virus and year of emerging, we found six of them are in our high-risk viral lists, includes HCoV-SARS-1, HCoV-SARS -2, HCoV- MERS, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-229E, CCoV-huPn-2018. In the six species, SARS-related CoVs poses a high probability of spillover by showing a large number in the natural hosts bats, and a wide species range in a list of secondary hosts (Figure 2A) [15,16]. A particular attention should be paid to alphaCoV1 and betaCoV1. Both viral species were widely carried by domestic animals or pet animals, which have a higher chance of human contact than wild animals. Indeed, in a phylogenetic analysis of the alpha- and beta-CoVs that caused diseases in humans or other domestic animals, we identified three major sources (Figure 2B and Supplementary Table 4). (1) AlphaCoV1, CoVs from this viral species caused diseases to swine, cat, dog, human and many other domestic or wild mammals, showing a wide species tropism. (2) The sub-genus Embecovirus, which were believed to have a rodent-origin [14]. It includes human OC43-CoV (betaCoV1), human HKU1-CoV, and a few other CoVs found in rodents or other mammals. Notably, Embecoviruses are the only CoVs that encode a Hemagglutinin-esterases protein, which may be derived from ancestral host lectin protein and may entitle Embecovirus a wide infection spectrum [17]. (3) A list of bat-origin CoV species, includes Sarbecovirus, Merbecovirus, 229E-, NL63-, HKU2- and HKU8-related CoVs. A common character for these bat-origin human diseases is that an intermediate host is normally involved. Interestingly, camel appears an important alternative host during a bat-human zoonotic transmission for MERS- (camel MERS-CoV), 229E- (camel 229E-like) and potentially HKU8-CoV (sero-positive) [18–20]. Other animals like civet, pangolin or swine may also be a second host for bat CoVs [15,21–23]. Lastly, it appears viral HE protein, APN- or ACE2-usage are advantageous for CoV cross-species transmission, as viruses with these characters crossed species barriers frequently (Figure 2B). The viruses that use DPP4 (Merbecovirus) or unknown receptors (HKU2/HKU8-CoV) may also have wide host range as shown in vitro [2,20,24,25].

Figure 2.

The zoonotic probability of alpha- and beta-CoVs. (A) Proposed CoV zoonotic events, particularly in humans. The proximate year of emerging, the number of viruses in that viral species and host range for each virus were shown. The year of emerging refers to literatures, and the host range details can be found in 2D. Notably, it is widely accepted that human CoVs, such as HCoV-SARS-1 or HCoV-SARS-2, have animal origins, albeit more direct evidence is needed. (B) CoV disease phylogeny. The most important CoV disease agents, as well as the related viruses from their natural hosts or intermediate hosts were analyzed. The important viral sub-genus or species were highlighted, and the receptors were also indicated. The eight CoVs that infected humans were shown in red. (C) The wildlife hosts of CoVs. The number of continents distributed for a certain host species, the number of CoVs found in that species and the viral species carried by this species were shown. As the most important natural host of CoVs, the details of the bats in genus level were indicated, whereas the details for rodents were not shown due to limited information available. The host species that may harbour SARSr-CoVs were indicated. The details for geographical distribution of each species can be found in Redlist (www.iucnredlist.org) (D) The spillover risk of CoVs and their respective host species. Four categories of risk levels were proposed using four different colors, and each viral species was connected to their natural or intermediate host species. The viral species and the sub-genus were shown on the right, while the host species in genus level (except rodents) and the host families were shown on the left. Four important host species, including Rhinolophus bat, Hipposideros bat, civet and camel were highlighted in brown, as they showed high probability to become a zoonotic source.

Next, we also analyzed the zoonotic source, which refers to the animals that spillover the virus to humans [26]. The zoonotic source could be a natural host that harbour a high genetic diversity of CoVs for long-term (e.g. bats) or an intermediate host (e.g. civets). We then analyzed the viral species, number of viruses and geographical distribution for each host carrying CoVs, which includes mainly bats, rodents and other wild mammals (Figure 2C and 2D). We found several bat species stand out as important zoonotic sources. For example, the phylogenic related Rhinolophidae and Hipposideridae bats, which harbour 3 or 5 CoV species each, were associated with human SARS-1, SARS-2, 229E and NL63 emergence, as well as swine SADS (HKU2) disease outbreak (Figure 2C and 2D) [16,21,27,28]. The Vespertilionidea bats consist of a large list of bat genus and they may harbour a large variety of high-risk CoV species as well, including MERSr-CoV (Vespertilio bats), HKU8-CoV (Miniopterus bats) and HKU4-CoV (Tylonycteris bats) that may cross the species barriers [25,29–31]. Pteropodidae bats only harbour the sub-genus Nobecovirus, in which the Rousettus HKU9-CoV demonstrated risk of spillover [30]. As the largest mammal species in the world, rodents mainly carry the sub-genus Embecovirus, where the human OC43-CoV and HKU1-CoV may originate (Figure 2B). Furthermore, other animals (e.g. civet) appear to play important role in CoV transmission chain, conferring which as important intermediate hosts [17] (Figure 2C and 2D). It is worth noting that pangolin emerges as important reservoir or intermediate host for Sarbecovirus or Merbecovirus, thus this animal may also play a role in CoV cross-species transmission chain [22,23,32]. Finally, it should also be emphasized that the important bat species, such as Rhinolophidae and Hipposideridae bats, distributed in at least four continents in the world, whereas the rodents and other small mammals have an even wider distribution [33]. Thus, a thorough understanding of CoVs carried by these wild animals in a wider geographical range appears necessary.

Collectively, we rank the spillover risk of all animal alpha- and beta-CoVs into four categories: (1) Those caused disease in human (6 CoV species); (2) those have not caused human disease but caused disease or have evidence of spillover to another animal (3 species); (3) no evidence of spillover or disease emergence but poses high-risk of spillover (11 species); (4) low-risk of spillover (17 species). Our analysis excluded HCoV-HKU1, HCoV-NL63 and swine PEDV viral species, as they were only found in the dead-end hosts (Figure 2D).

Sero-diagnosis for high-risk CoVs

Based on these criteria, we established a panel of serological detection systems for 16 high-risk CoVs identified above, or 15 CoV species as we made both HCoV-SARS-1 and HCoV-SARS-2 for Sarbecovirus (Figure 3A and Supplementary Table 5). Notably, a few proposed high-risk viruses were not included for serological detection, as they are either not discovered yet, not been classified as an individual CoV species or not been classified as high risk (low number and diversity) during the designing of the project.

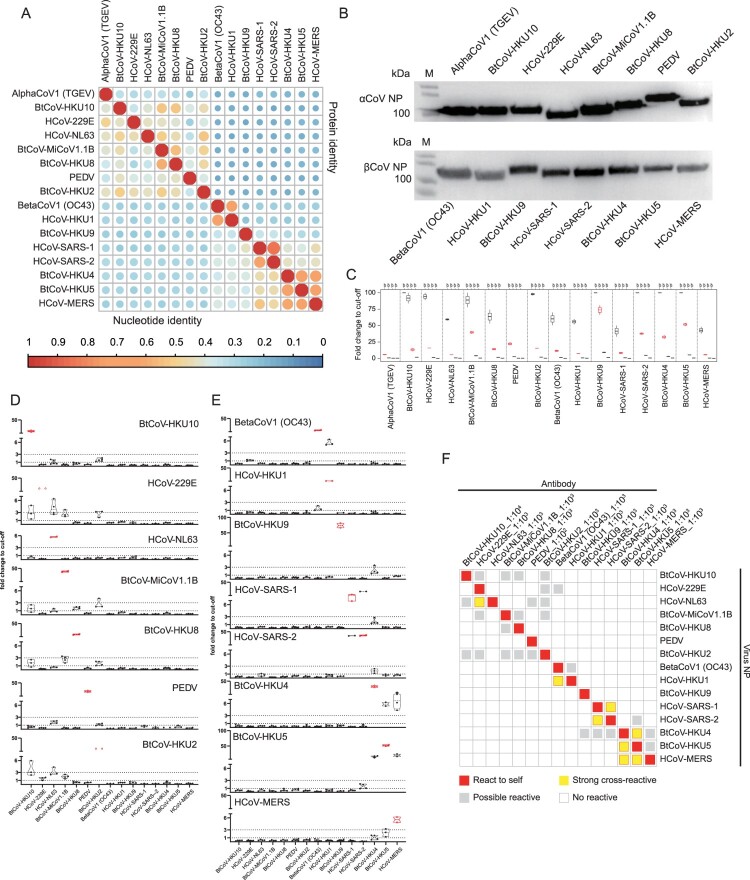

Figure 3.

Sero-diagnosis for zoonotic high-risk CoVs. (A) Sequence alignment of the selected CoV NP based on nucleic acid or amino acid. The sequence information can be found in Supplementary table 5. (B) Expression analysis of NP-based LIPS by WB using antibody against the tag in pREN2 vector. (C) LIPS performance using corresponding rabbit hyper-immune serum. For each antigen, antibody was tested at a 10-fold dilution, ranging from 10−2 to 10−5. Eight naïve rabbit serum samples were used as negative control. The highest dilution that showed up as positive (fold change to cut-off > 5 or 10) was chosen as the optimal dilution for cross-reaction with other antigens, shown as red in the figure. (D) Sero cross-reaction between a panel of rabbit sera against alpha-CoV and 15 NP in LIPS. (E) Cross-reaction between a panel of rabbit sera against beta-CoV NP and 15 NP in LIPS. For D and E, the antigen used in LIPS was shown on the x-axis, while the tested antibody was indicated on the figure. The y-axis indicated fold change to cut-off. Values between 1 and 3 were defined as “grey area” (between two dotted lines), indicating possible cross-reactive. Red dots indicate NP reaction to rabbit serum raised against self (F) Overview of the sero-cross reactivity.

As a sensitive and quick serological tool, the luciferase immunoprecipitation system (LIPS) demonstrated advantages over classical ELISA during disease emergence [34]. Based on our successful experiences on HKU2-CoV and HKU8-CoV [20,21], we established nucleocapsid protein (NP)-based LIPS assays for the 15 CoV species. We also made hyper-immune rabbit sera against purified NP for each virus as positive controls for LIPS assay, as clinical serum samples were not available for most of these CoVs.

The sequence alignment results indicated that a high intra-genus similarity for CoVs NP, while the inter-genus similarity is very low. The intra-genus protein similarity is much higher for alpha-CoVs than beta-CoVs (Figure 3A), probably due to the complexed evolutionary origin of alpha-CoVs caused by inter-family host-switching [30]. This NP similarity would possibly influence the serological detection specificity. We first tested the detection efficiency for each virus using their corresponding rabbit sera and determined an optimal dilution for each virus (Figure 3B and 3C). The data indicated that the LIPS assay successfully detected their respective rabbit serum, except TGEV. Next, we determined the detection specificity for each antigen using a list of CoV rabbit sera. Each NP was subjected to react with all 15 sera under optimal dilution. Due to the high sensitivity of LIPS, we defined the results with values (fold change to cut-off) between 1 and 3 as “grey area” (possible cross-reactive), whereas those higher than 3 or lower than 1 as absolute positive or absolute negative (Figure 3D and 3E). Our tests successfully picked up the known cross-reactions, including HCoV-HKU1 with HCoV-OC43, HCoV-SARS-1 with HCoV-SARS-2 or BtCoV-HKU4, BtCoV-HKU5 with HCoV-MERS. The results also indicated a cross-reaction between HCoV-NL63 and HCoV-229E. Moreover, a few possible cross-reaction can also be found, particularly within alpha-CoVs (Figure 3F). Some viruses appeared more easily to cross-react with others, including BtCoV-HKU2 and BtCoV-HKU10 to other alpha-CoVs, which was very much related to their NP protein similarity to other CoVs (Figure 3A).

To validate the cross-reaction results obtained by LIPS, we later developed a series in-house anti-NP IgG ELISA methods using hyper-immune rabbit sera. As shown in the figure, ELISA results matched well with the LIPS data, though LIPS appeared more sensitive (Supplementary Figure 2).

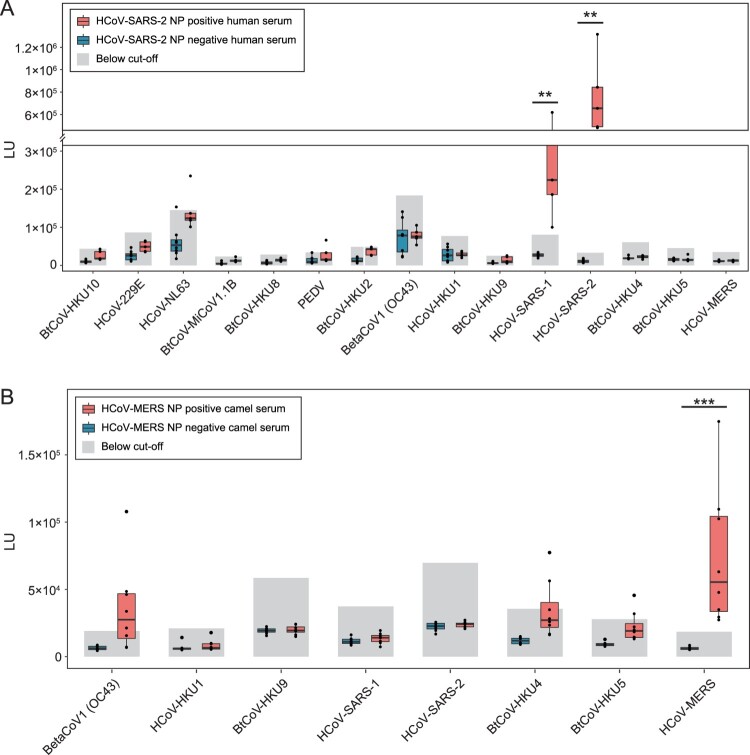

Validation of CoV serological tests using clinical serum samples

Lastly, we ought to determine if this LIPS system applied to clinical samples. For this purpose, we collected serum samples from human COVID-19 patients or from MERS-CoV sero-positive camels, as well as negative serum samples for each. Serology detection was used during the HCoV-SARS-2 origin investigation. We then detected whether HCoV-SARS-2 NP positive human serum was reactive to all other 15 viruses. Clear cross-reaction could only be determined for HCoV-SARS-1, whereas no other alpha-CoV or beta-CoV species tested here showed reaction to COVID-19 patient sera. Notably, although the common cold viruses HCoV-NL63 tested positive, they did not follow a same positive–negative pattern as HCoV-SARS-2. Thus, the positivity should be from a general common cold infection, which may also explain a high betaCoV1 (OC43) detection baseline (Figure 4A). For HCoV-MERS, the pattern is like that using rabbit sera, showing a cross-reactivity between HCoV-MERS, BtCoV-HKU4 and BtCoV-HKU5 (Figure 4B). We did not test the sero-cross reactivity against alpha-CoVs, as which showed unlikely using rabbit sera. Notably, the beta-CoV (OC43) sero-positive should reflect a high prevalence of camel HKU23-CoV, which belongs to betaCoV1 [35].

Figure 4.

Sero-cross reactivity between CoV-LIPS and SARS-CoV-2 or MERS-CoV clinical samples. (A) Reaction between 15 NP and serum samples collected from patients with COVID-19. Eight negative (blue) and 5 positive samples (red), defined using ELISA kit, were used in the LIPS. (B) Reaction between 8 beta-CoV NP and HCoV-MERS NP positive camel serum. Eight negative (blue) and 8 positive samples (red) were used for detection in LIPS. The detection cut-off was shown for each antigen.

Discussion

In this manuscript, we conducted comprehensive analysis to all known alpha and beta coronavirus species and pinpointed a list of 20 CoV species with high risk of human spillover, which could be the causative agent of a future outbreak. We also identified important zoonotic sources, including natural hosts bats (Rhinolophus and Hipposideros) and rodents, or possible intermediate hosts camel, civet, swine or pangolin. Subsequently, we established quick and sensitive serological tools that could be used for active surveillance for these high-risk CoV species. Our study provided a theoretical or practical basis for future CoV disease preparedness.

Our risk assessment is mainly focused on CoV viral traits, which is different to most previous studies that based on ecology models or expert opinions [6–9]. First, as CoV emergence was mainly from zoonotic transmission [2], our analysis is angled from natural host’s perspective. If we consider infection as a series of breaking bottlenecks, then the viral infection enters the host as diverse quasi-species to establish infection, and the virus with the best fitness was selected [36]. Thus, it is easier to understand that the viral species that have a large population and high genetic diversity (to form a pool of quasi-species) in the natural hosts would have some advantages of infecting another host over the other viral species. For example, although the ACE2-using SARSr-CoV only takes a small percentage in this viral species in bats, the overall large number and high genetic diversity enabled the possible emergence of the progenitor virus of HCoV-SARS-1, as nearly all building blocks could be found in bats [27]. Second, we also learned from past CoV zoonotic events. It is undeniable that if a CoV species caused disease emergence before, there is high chance for it to cause outbreak in future. In addition, by analyzing the viral receptor or the hosts carrying the disease-causing CoV species, we would understand the common characters of historical CoV emergence. For example, APN-usage or rodent-origin likely represents sufficient conditions for wide species range (Figure 2B). By our understanding, there is no such CoV risk assessment that focus on the majority of lesser-known CoV species yet.

Our analysis classified the risk of human spillover into four categories. The CoV species causing human disease would likely be a causative agent of a future outbreak, and the bat-carried ACE2-usage SARSr-CoV, camel MERS-CoV or domestic mammals carried alphaCoV1 and betaCoV1 would be the hotspots. What should be emphasized are the CoV species with evidence of spillover, but not yet to human, including BtCoV-HKU2 (caused swine disease), BtCoV-HKU4 (use DPP4 receptor, jumped to pangolin) and BtCoV-HKU8 (jump to camel and civet) [20,21,32]. They have jumped to species that ecologically overlapped with humans and showed characters of wide infection range in vitro or in vivo [20,24,25,31]. There is high chance for these viruses to jump over to humans following favorable ecological or virological changes in the second hosts. The third categories included a list of high-risk, but barely studied CoV species. We should not underestimate their risk of spillover, albeit neither the viral receptor nor their host ranges were known. It is also highly probable that new spillover events would be discovered following more surveillance targeting at these viruses. Finally, the presence of low-risk CoVs and a lot of unclassified CoVs that are not included in the study indicated more of a knowledge boundary of CoVs, rather than that they are not important.

Bats and rodents are arguably the most important natural hosts of alpha- and beta-CoVs. As the second largest mammal species in the world, bats carry large varieties of CoV species, indicating a unique co-existence between bats and CoVs [37]. The phylogenic related Rhinolophus and Hipposideros bats, which were classified as one genus previously, harbour more human-threatening CoV species than other bats. Rhinolophus bats may carry SARSr-CoVs, BtCoV-HKU2 and BtCoV-Rf2013, while Hipposideros bats may carry HCoV-229Er, HCoV-NL63r, BtCoV-HKU10 and BtCoV-ZJ2013, all high-risk CoVs in our analysis. Interestingly, as the first largest mammal species, rodents mainly carry the sub-genus Embecovirus. Besides these natural reservoir hosts, certain species appears as important intermediate hosts that bridge natural hosts and humans. The most important ones include camels and pigs, the two domestic mammals. Others also include games animals such as civets, pangolins and hedgehogs. Surveillance of high-risk viruses in these animals should be conducted in future.

In conclusion, we conducted comprehensive assessment and sero-diagnosis to coronaviruses with risk of human spillover. Our work serves as a theoretical or practical basis for future CoV disease preparedness.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Peter Burbelo from NIH, and Professor Lin-Fa Wang from Singapore Duke-Nus medical school for helping with the LIPS system. We thank Dr. Ning Wang, WIV graduate, for her support on protein expression and purification. We also thank Professor Gui-Qing Peng from Huazhong Agricultural University for kindly providing rabbit polyclonal antibody against TGEV and PEDV NP. We appreciate the help from the WIV animal facility for preparing rabbit hyper-immune sera.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by National Key R&D program of China: [Grant Number 2021YFC2300901]; R&D Program of Guangzhou Laboratory: [Grant Number SPRG22-001]; the Strategic Priority Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences: [Grant Number XDB29010204]; the Strategic Priority Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences: [Grant Number XDB29010101].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- 1.Tan CW, Yang X, Anderson DE, et al. Bat virome research: the past, the present and the future. Curr Opin Virol. 2021 Aug;49:68–80. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2021.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cui J, Li F, Shi ZL.. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019 Mar;17(3):181–192. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vora NM, Hannah L, Lieberman S, et al. Want to prevent pandemics? Stop spillovers. Nature. 2022 May;605(7910):419–422. doi: 10.1038/d41586-022-01312-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou P, Yang X-L, Wang X-G, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020 Mar;579(7798):270. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.taxonomy I . Available from https://ictv.global/taxonomy; 2022.

- 6.Geoghegan JL, Senior AM, Di Giallonardo F, et al. Virological factors that increase the transmissibility of emerging human viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016 Apr 12;113(15):4170–4175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521582113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olival KJ, Hosseini PR, Zambrana-Torrelio C, et al. Host and viral traits predict zoonotic spillover from mammals. Nature. 2017 Jun 29;546(7660):646–650. doi: 10.1038/nature22975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mollentze N, Streicker DG.. Viral zoonotic risk is homogenous among taxonomic orders of mammalian and avian reservoir hosts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020 Apr 28;117(17):9423–9430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1919176117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grange ZL, Goldstein T, Johnson CK, et al. Ranking the risk of animal-to-human spillover for newly discovered viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021 Apr 13;118(15). doi: 10.1073/pnas.2002324118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warren CJ, Sawyer SL.. How host genetics dictates successful viral zoonosis. PLoS Biol. 2019 Apr;17(4):e3000217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehand MS, Al-Shorbaji F, Millett P, et al. The WHO R&D blueprint: 2018 review of emerging infectious diseases requiring urgent research and development efforts. Antiviral Res. 2018 Nov;159:63–67. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vlasova AN, Diaz A, Damtie D, et al. Novel canine coronavirus isolated from a hospitalized patient with pneumonia in East Malaysia. Clin Infect Dis. 2022 Feb 11;74(3):446–454. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han Y, Du J, Su H, et al. Identification of diverse bat alphacoronaviruses and betacoronaviruses in China provides new insights into the evolution and origin of coronavirus-related diseases. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1900. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lau SK, Woo PC, Li KS, et al. Discovery of a novel coronavirus, China Rattus coronavirus HKU24, from Norway rats supports the murine origin of Betacoronavirus 1 and has implications for the ancestor of Betacoronavirus lineage A. J Virol. 2015 Mar;89(6):3076–3092. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02420-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guan Y, Zheng BJ, He YQ, et al. Isolation and characterization of viruses related to the SARS coronavirus from animals in southern China. Science. 2003 Oct 10;302(5643):276–278. doi: 10.1126/science.1087139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu B, Guo H, Zhou P, et al. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-00459-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forni D, Cagliani R, Clerici M, et al. Molecular evolution of human coronavirus genomes. Trends Microbiol. 2017 Jan;25(1):35–48. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reusken CB, Haagmans BL, Muller MA, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus neutralising serum antibodies in dromedary camels: a comparative serological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013 Oct;13(10):859–866. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70164-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corman VM, Eckerle I, Memish ZA, et al. Link of a ubiquitous human coronavirus to dromedary camels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016 Aug 30;113(35):9864–9869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1604472113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang W, Zheng X-S, Agwanda B, et al. Serological evidence of MERS-CoV and HKU8-related CoV co-infection in Kenyan camels. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2019 Jan 1;8(1):1528–1534. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2019.1679610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou P, Fan H, Lan T, et al. Fatal swine acute diarrhoea syndrome caused by an HKU2-related coronavirus of bat origin. Nature. 2018 Apr 12;556(7700):255. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0010-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lam TT, Jia N, Zhang YW, et al. Identifying SARS-CoV-2-related coronaviruses in Malayan pangolins. Nature. 2020 Jul;583(7815):282–285. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen J, Yang X, Si H, et al. A bat MERS-like coronavirus circulates in pangolins and utilizes human DPP4 and host proteases for cell entry. Cell. 2023;186(4):850–863.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.01.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luo Y, Chen Y, Geng R, et al. Broad cell tropism of SADS-CoV in vitro implies its potential cross-species infection risk. Virol Sin. 2021 Jun;36(3):559–563. doi: 10.1007/s12250-020-00321-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He WT, Hou X, Zhao J, et al. Virome characterization of game animals in China reveals a spectrum of emerging pathogens. Cell. 2022 Mar 31;185(7):1117–1129 e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.02.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corman VM, Muth D, Niemeyer D, et al. Hosts and sources of endemic human coronaviruses. Adv Virus Res. 2018;100:163–188. doi: 10.1016/bs.aivir.2018.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu B, Zeng LP, Yang XL, et al. Discovery of a rich gene pool of bat SARS-related coronaviruses provides new insights into the origin of SARS coronavirus. PLoS Pathog. 2017 Nov;13(11):e1006698. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tao Y, Shi M, Chommanard C, et al. Surveillance of bat coronaviruses in Kenya identifies relatives of human coronaviruses NL63 and 229E and their recombination history. J Virol. 2017 Mar 1;91(5). doi: 10.1128/JVI.01953-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luo CM, Wang N, Yang XL, et al. Discovery of novel bat coronaviruses in south China that use the same receptor as Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Virol. 2018 Jul 1;92(13). doi: 10.1128/jvi.00116-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Latinne A, Hu B, Olival KJ, et al. Origin and cross-species transmission of bat coronaviruses in China. Nat Commun. 2020 Aug 25;11(1):4235. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17687-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 31.Yang Y, Du L, Liu C, et al. Receptor usage and cell entry of bat coronavirus HKU4 provide insight into bat-to-human transmission of MERS coronavirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014 Aug 26;111(34):12516–12521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405889111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi W, Shi M, Que TC, et al. Trafficked Malayan pangolins contain viral pathogens of humans. Nat Microbiol. 2022 Aug;7(8):1259–1269. doi: 10.1038/s41564-022-01181-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.redlist I . Available from https://www.iucnredlist.org/en; 2022.

- 34.Burbelo PD, Hoshino Y, Leahy H, et al. Serological diagnosis of human herpes simplex virus type 1 and 2 infections by luciferase immunoprecipitation system assay. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2009 Mar;16(3):366–371. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00350-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Woo PC, Lau SK, Fan RY, et al. Isolation and characterization of dromedary camel coronavirus UAE-HKU23 from dromedaries of the Middle East: minimal serological cross-reactivity between MERS coronavirus and dromedary camel coronavirus UAE-HKU23. Int J Mol Sci. 2016 May 7;17(5). doi: 10.3390/ijms17050691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meyer B, Drosten C, Muller MA.. Serological assays for emerging coronaviruses: challenges and pitfalls. Virus Res. 2014 Dec 19;194:175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.03.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang LF, Cowled C.. Bats and viruses: a new frontier of emerging infectious diseases [Book Review]. Choice: Curr Rev Acad Lib. 2016;53(6):901–901. PubMed PMID: 112611943. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.