ABSTRACT

Acute methanol poisoning is first and foremost life-threatening. Otherwise, functional prognosis is mainly based on ocular impairment. In this case series we aimed to describe the ocular manifestations after acute methanol poisoning during an outbreak in Tunisia. The data from 21 patients (41 eyes) were analysed. All patients underwent a complete ophthalmological examination including visual fields, colour vision test and optical coherence tomography with evaluation of the retinal nerve fibre layer. Patients were classified into two groups. Group 1 included patients with visual symptoms and group 2 included patients with no visual symptoms. Ocular abnormalities were seen in 81.8% of patients with ocular symptoms. They included: optic neuropathy in 7 patients (63.6%); central retinal artery occlusion in 1 patient (9.1%); and central serous chorioretinopathy in 1 patient (9.1%). Mean blood methanol levels were significantly higher in patients without ocular symptoms (p = .03).

KEYWORDS: Methanol poisoning, acute poisoning, ocular findings, outbreak, case series

Introduction

Methanol or methyl alcohol is a clear, colourless, volatile and flammable liquid produced from the distillation and fermentation of sugars in wood. It is widely used as a solvent in many commercial and consumer products, notably in washer fluid, perfumes, anti-freeze and model airplane fuel. It is also increasingly being used as a renewable energy alternative. If it is sold as adulterated alcohol use, then it can be a major public health concern, as was the case during the COVID-19 pandemic when it was responsible for the deaths of 700 people in Iran.1 It can also be illegally found in alcohol-based hand rubs and cases of death have been reported after the ingestion of hand sanitiser.2

The incidence of methanol poisoning outbreaks has increased in recent years, mainly in the form of clusters.3–5 In and of itself, methanol has a relatively low intrinsic toxicity, however, it is metabolised to highly toxic compounds, particularly formaldehyde and formic acid, which can cause visual abnormalities, metabolic disturbances and neurological dysfunction that are often life-threatening.3

The impact of methanol ingestion can range from nausea, vomiting, headache, and dyspnoea to stupor, coma, convulsions, hypothermia, central nervous system damage and death. The severity of symptoms correlates with the severity of the induced acute metabolic acidosis.4 Visual disturbances due to the toxic effect of methanol can be transient or permanent.6 Ocular manifestations typically occur 12 to 24 hours following methanol ingestion,7 varying from transient blurred vision, toxic optic neuropathy to complete blindness.

The purpose of this study was to describe the ocular manifestations of acute methanol poisoning during an outbreak in Tunisia.

Methods

Study design and setting

This is a case series including patients diagnosed with acute methanol poisoning following the ingestion of cologne and adulterated alcohol from an illicit production who were hospitalised in the department of intensive care medicine and clinical toxicology (CAMU) in Tunis, Tunisia, during an outbreak in 2020. All patients underwent a complete ophthalmological examination in the ophthalmology department of Habib Thameur hospital in Tunis, Tunisia, including measurement of best-corrected Snellen visual acuity (VA), pupillary examination, Lanthony Desaturated D-15 colour vision testing, automated 24–2 visual field testing, slit-lamp examination and dilated fundus examination. Normal colour vision was defined as normal trichromacy and defective colour vision was defined as mild, moderate or severe abnormal trichromacy or dichromacy. Reliability indices (name, demographic data, fixation loss, false positive and false negative) were verified before interpretation of the automated visual fields. Mean retinal nerve fibre layer (RNFL) thickness was assessed from images acquired using the swept source optical coherence tomography (OCT) (DRI-OCT-1, Topcon, Tokyo, Japan). The study protocol followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients were classified into two groups. Group 1 included patients with ocular symptoms and group 2 included patients without ocular symptoms.

The diagnosis of toxic optic neuropathy was made on clinical grounds first based on the history (methanol poisoning confirmed by the methanol blood level in all patients) and the presence of a relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD), optic disc swelling, a visual field defect and/or a colour vision defect.

Patients’ management during their hospitalisation in the intensive care department

The protocol of treatment followed the consensus statement in patients with methanol poisoning during outbreaks.8 Patients with severe metabolic acidosis (pH <7.3) were administered intravenous sodium bicarbonate and plasma volume expansion with isotonic irrigating fluid. All patients were treated with intravenous cofactor therapy folinic acid (50 mg every 6 hours) and ethanol (loading dose: 600–700 mg/kg followed by a maintenance dose of 154 mg/kg/h). The use of dialysis was individualised on the basis of the presence of metabolic acidosis (pH <7.3), coma or seizures, acute renal failure, refractory metabolic acidosis or methanolaemia >0.09 g/l.

Laboratory investigations

We analysed mean methanol blood level (g/l), arterial pH measured on admission (normal range: 7.35 to 7.45, acidaemia was defined as a pH <7.35). Blood sodium bicarbonate (HCO3−) level (normal range: 22 to 26 mEq/L), potassium (normal range: 3.5 to 5 mmol/l), and the anion gap were measured. The anion gap was calculated as follows: ([Na+] + [K+]) − ([Cl−] + [HCO3−]) (normal range: 16 ± 4 mEq/L).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software version 21 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Descriptive statistics (percentages, means and standard deviation) were computed for demographic and clinical variables. The Mann Whitney test was used to analyse differences in baseline clinical characteristics between patients in the two groups (between the worse eye of patients with ocular symptoms and the right eye of patients without ocular symptoms).

Results

The data of 41 eyes from 21 patients (one patient was one-eyed) with no previous past medical history were analysed. Twenty patients presented with intentional methanol ingestion and one patient had had accidental ingestion. The median age of the patients was 31 years (range: 16–69 years). All of the patients were male. A medical history of chronic ethanol consumption was noted in seven of the patients (33.3%). The mean time of admission into the intensive care unit following the methanol poisoning was 67 hours. Dialysis was indicated for 12 patients (57.1%). The laboratory investigations are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Laboratory markers measured on admission.

| Group 1 | Group 2 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean methanol blood level (g/l) | 0.42 ± 0.5 | 0.97 ± 0.6 | .03 |

| pH | 7.23 ± 0.2 | 7.3 ± 0.1 | .3 |

| Mean blood bicarbonate level (mEq/L) | 12.6 ± 6.9 | 12.7 ± 4.4 | .7 |

| Mean blood potassium level (mmol/l) | 3.66 ± 0.6 | 3.42 ± 0.4 | .2 |

| Anion gap (mEq/L) | 18.77 ± 6.6 | 21.1 ± 5.3 | .6 |

Mean values ± standard deviation.

Patients were examined in the ophthalmology department a mean of 4 days after the time of admission (range: 2–8 days). There were 11 (52.7%) Group 1 patients with ocular symptoms and 10 group 2 patients (47.6%) without ocular symptoms. The ocular symptoms were: blurred vision in five patients (45.4%); decreased visual acuity in five patients (45.4%) and a central scotoma in one patient (9.1%).

The baseline characteristics and ophthalmological examination findings are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics and fundus examination findings.

| Group 1 (11 patients, 22 eyes) | Group 2 (10 patients, 19 eyes) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 32 ± 14.9 | 31.6 ± 11 | .9 |

| Chronic alcohol exposure (%) | 5 (45.4%) | 2 (20%) | .2 |

| Mean best corrected Snellen visual acuity | 20/100 (range 20/4000 to 20/20) | 20/25 (range 20/32 to 20/20) | .03 |

| Number of eyes with a relative afferent pupillary defect (%) | 2 (9.1%) | - | |

| Fundus examination findings: | |||

| Optic disc swelling (%) | 3 (13.6%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Normal looking fundus (%) | 16 (72.7%) | 19 (100%) | |

| Other findings (%) | 3 (13.6%) | ||

| Posterior pole retinal whitening (2, 9.1%) | |||

| Macular subretinal fluid (1, 4.5%) | |||

| Visual field findings: | |||

| Mean deviation (db) | 1.77 ± 1.3 | 1.62 ± 0.7 | |

| Unreliable visual field (%) | 11 (50%) | 5 (26.3%) | |

| Normal visual field (%) | 7 (31.8%) | 14 (73.7%) | |

| Abnormal visual field (%) | 4 (18.2%) | - | .9 |

| Colour blindness test findings: | |||

| Unreliable colour blindness test (%) | 10 (45.5%) | 5 (26.3%) | |

| Normal colour blindness test (%) | 9 (40.9%) | 14 (73.7%) | |

| Abnormal colour blindness test (%) | 3 (13.6%) | - | |

| Mean RNFL thickness (µm) | 112.4 ± 18 | 106.8 ± 7.7 | .2 |

Mean values ± standard deviation.

RNFL = retinal nerve fibre layer.

The mean blood methanol level was significantly higher in patients without ocular symptoms (p = .03). We did not note any statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of age, arterial pH, or anion gap (p = .9, .3, and .6 respectively). Mean best corrected VA was significantly worse in group 1 patients (p = .03). Ocular abnormalities were seen in 81.8% of patients with ocular symptoms (Table 3). They included: optic neuropathy in seven patients (63.6%) (Figure 1); central retinal artery occlusion in one patient (9.1%); and central serous chorioretinopathy in one patient (9.1%) (Figure 2).

Table 3.

Ophthalmological examination abnormalities.

| Group 1 (11 patients) | Group 2 (10 patients) | |

|---|---|---|

| Optic neuropathy (%) | 7 (63.6%) | - |

| Unilateral involvement (%) | 2 (18.2%) | - |

| Bilateral involvement (%) | 5 (45.4%) | - |

| Oedematous optical neuropathy (%) | 2 (18.2%) | - |

| Retrobulbar optic neuropathy (%) | 5 (45.4%) | - |

| Central retinal artery occlusion (%) | 1 (9.1%) | - |

| Central serous chorioretinopathy (%) | 1 (9.1%) | - |

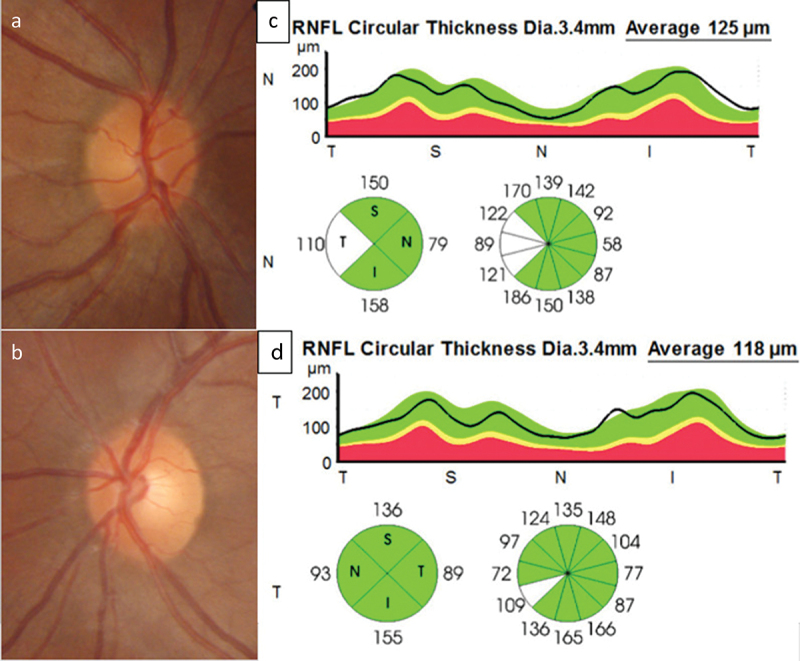

Figure 1.

A 20-year-old male was admitted 4 days following methanol ingestion complaining of abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting with acute persistent blurred vision in the right eye (OD). His pH was 7.3, anion gap was 16.34 mEq/L and his blood methanol level was 0.07 g/l. He did not receive dialysis. Ocular examination 5 days following the ingestion found his visual acuity was 20/20 in each eyes with a relative afferent pupillary defect iOD. Colour optic nerve photographs showed a swollen hyperaemic optic disc OD with filling in of the optic disc cup (a), normal appearance of the left (OS) optic disc with a cup-to-disc ratio of 0. 3 (b). Optical coherence tomography of the retinal nerve fibre layer showed temporal increased thickness in OD (c) compared with OS (d).

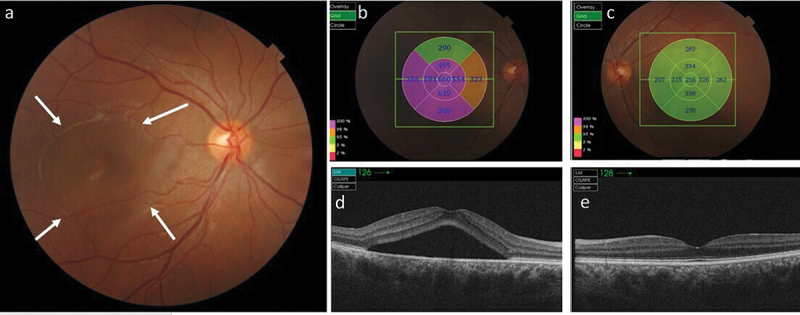

Figure 2.

A 25-year-old male was admitted 4 days following methanol ingestion complaining of acute persistent right eye (OD) blurred vision. His pH 7.37, anion gap was 22.5 mEq/L, and his blood methanol level was 0.018 g/l. He did not receive dialysis. Ocular examination was performed 5 days following the ingestion. His visual acuity was 20/25 in OD and 20/20 in the left eye (OS). (a) Colour fundus photographs of OD showed acute central serous chorioretinopathy presenting as central serous neurosensory retinal detachment (between white arrows). (b, c) representive photographic images of the fundus with grid graph of measurements indicating an increase of macular thickness in OD (b) compared with OS (c). (d, e) Swept-source optical coherence tomography indicated the presence of an optically empty space corresponding to the subretinal fluid beneath the fovea without retinal pigment epithelium detachment in OD (d) compared with OS (e). The choroid was thick in both eyes.

We tried to conduct long-term follow-up but 14 patients had economic difficulties and were lost to follow-up. Only two patients from group 1 and five patients from group 2 returned for re-examination, so we could not obtain any meaningful data.

Discussion

In this study we evaluated ocular abnormalities after severe acute methanol poisoning. We assessed ophthalmological findings of 21 patients diagnosed with acute methanol poisoning requiring medical intensive care. All of the patients were young or middle-aged males. The mean blood methanol level was significantly higher in patients without ocular symptoms (p = .03). We hypothesise that the absence of a positive correlation between mean blood methanol level and ocular symptoms may suggest that, even with very low blood levels, ocular toxicity thresholds may be reached. This can be explained by a major sensitivity of ocular structures to methanol-derived toxins. Some have studies demonstrated that the incidence of ocular abnormalities correlated with the volume of methanol consumed,9 while other authors have shown an absence of correlation.10 It is noteworthy that some factors may influence methanol toxicity and enhance its effect like the concomitant ingestion of ethanol or the treatment administered.3,11

The most frequent ocular abnormality in our study was optic neuropathy, which correlates with previous reports.1,6,10 It has been demonstrated that formic acid, the toxic metabolite of methanol, prevents mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation by inhibiting cytochrome oxidase activity in the laminar and retrolaminar regions of the optic nerve.12 Histopathological studies have documented disruption of axonal flow, mitochondrial oedema, fragmentation of neurotubules and neurofilaments, and axonal blistering. They have also described alterations in glial cells, including astrocytic oedema and oedema of the oligodendroglial cytoplasm.1,13

In our study, one patient presented with acute bilateral vision loss secondary to bilateral transient central retinal artery occlusion. Previous studies have demonstrated retinal toxicity due to methanol.3,14 Patients may present with cystoid macular oedema, pseudo-cherry red spot, retinal haemorrhages and engorgement of the retinal veins.3 The pathogenesis of vascular occlusion secondary to methanol poisoning has yet to be demonstrated.

The clinical findings in one patient were consistent with the diagnosis of central serous chorioretinopathy, which has also been previously reported in a patient with methanol-induced optic neuropathy associated with bilateral serous retinal pigment epithelial detachment.15 The presence of central serous chorioretinopathy could be explained by intensive care stay and stress but also by the direct toxicity of methanol on the retinal pigment epithelium.16,17

Our results show that ocular abnormalities were seen in 81.8% of patients with ocular symptoms. The ophthalmological examination was within normal limits in two patients with ocular symptoms. Taking a history can be difficult in intoxicated patients. We suggest that ophthalmological examination is indicated in all patients with methanol intoxication to detect ocular abnormalities.

Long-term follow-up of patients with methanol ingestion is recommended. In a case series by Zakharov et al. of 50 patients with confirmed methanol poisoning, 14% were discharged with visual sequelae and 12% with both visual and central nervous system sequelae. On follow-up 22% of patients discharged without visual sequelae had abnormal RNFL thicknesses and visual evoked potentials.18 Nurieva et al. followed 42 patients after methanol poisoning over 4 years and reported abnormal RNFL thicknesses most significant in the temporal sector and chronic axonal loss in 24% of the patients.19

Our study has several limitations including its case series design with lack of longitudinal data and the sample size. This outbreak was not the first reported incident in Tunisia,20 and will certainly not be the last, due to the trade in illegal homemade alcoholic beverages that replace ethanol with cheap methanol. The upsurge during the COVID-19 pandemic was caused by the reduction in the amount of ethanol on the market and the several lockdowns.21

Conclusion

Acute methanol poisoning is a major global health problem, especially in developing countries. It often affects young and healthy males and can cause death or severe ocular damage, particularly toxic optic neuropathy. Ophthalmological examination should be indicated in all patients with methanol intoxication. Long-term follow-up is recommended to detect ocular sequelae.

Funding Statement

The authors reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- 1.Mehrpour O, Sadeghi M.. Toll of acute methanol poisoning for preventing COVID‑19. Arch Toxicol. 2020;94(6):2259–2260. doi: 10.1007/s00204-020-02795-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alan PLC, Thomas YKC.. Methanol as an unlisted ingredient in supposedly alcohol-based hand rub can pose serious health risk. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(7):1440. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15071440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pressman P, Clemens R, Sahu S, Hayes AW. A review of methanol poisoning: a crisis beyond ocular toxicology. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2020;39(3):173‑9. doi: 10.1080/15569527.2020.1768402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paasma R, Hovda KE, Moghaddam HH, et al. Risk factors related to poor outcome after methanol poisoning and the relation between outcome and antidotes – a multicenter study. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2012;50(9):823–831. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2012.728224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desai T, Sudhalkar A, Vyas U, Khamar B. Methanol poisoning: predictors of visual outcomes. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(3):358‑64. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanaei-Zadeh H, Zamani N, Shadnia S. Outcomes of visual disturbances after methanol poisoning. Clin Toxicol Phila Pa. 2011;49:102‑7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seme MT, Summerfelt P, Neitz J, Eells JT, Henry MM. Differential recovery of retinal function after mitochondrial inhibition by methanol intoxication. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:834–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hassanian-Moghaddam H, Zamani N, Roberts DM, et al. Consensus statements on the approach to patients in a methanol poisoning outbreak. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2019;57(12):1129–1136. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2019.1636992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dethlefs R, Naraqi S. Ocular manifestations and complications of acute methanol intoxication. Med J Aust. 1978;2(10):483‑5. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1978.tb131655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma P, Sharma R. Toxic optic neuropathy. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2011;59:137–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galvez-Ruiz A, Elkhamary SM, Asghar N, Bosley TM. Visual and neurologic sequelae of methanol poisoning in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2015;36(5):568‑74. doi: 10.15537/smj.2015.5.11142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grzybowski A, Zülsdorff M, Wilhelm H, Tonagel F. Toxic optic neuropathies: an updated review. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 2015;93(5):402‑10. doi: 10.1111/aos.12515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moschos MM, Gouliopoulos NS, Rouvas A, Ladas I. Vision loss after accidental methanol intoxication: a case report. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6(1):479. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hovda K, McMartin K, Jacobsen D. Methanol and Formaldehyde Poisoning. Basel, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ranjan R, Kushwaha R, Gupta RC, Khan P. An unusual case of bilateral multifocal retinal pigment epithelial detachment with methanol-induced optic neuritis. J Med Toxicol. 2014;10(1):57–60. doi: 10.1007/s13181-013-0329-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKellar MJ, Hidajat RR, Elder MJ. Acute ocular methanol toxicity: clinical and electrophysiological features. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1997;25:225–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.1997.tb01397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Treichel JL, Henry MM, Skumatz CM, Eells JT, Burke JM. Antioxidants and ocular cell type differences in cytoprotection from formic acid toxicity in vitro. Toxicol Sci. 2004;82(1):183–192. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfh256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zakharov S, Pelclova D, Diblik P, et al. Long-term visual damage after acute methanol poisonings: longitudinal cross-sectional study in 50 patients. Clin Toxicol Phila Pa. 2015;53(9):884‑92. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2015.1086488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nurieva O, Diblik P, Kuthan P, et al. Progressive chronic retinal axonal loss following acute methanol-induced optic neuropathy: four-year prospective cohort study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;191:100‑15. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2018.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brahmi N, Blel Y, Abidi N, et al. Methanol poisoning in Tunisia: report of 16 cases. Clin Toxicol. 2007;45(6):717–720. doi: 10.1080/15563650701502600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Razieh SMR, Arzhangzadeh M, Safaei-Firouzabadi H, et al. Methanol poisoning during COVID-19 pandemic; a systematic scoping review. Am J Emerg Med. 2022;52:69–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2021.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]