Abstract

Background:

Limited research captures the intersectional and nuanced experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, two-spirit, and other sexual and gender-minoritized (LGBTQ2S+) people when accessing perinatal care services, including care for pregnancy, birth, abortion, and/or pregnancy loss.

Methods:

We describe the participatory research methods used to develop the Birth Includes Us survey, an online survey study to capture experiences of respectful perinatal care for LGBTQ2S+ individuals. From 2019 to 2021, our research team in collaboration with a multi-stakeholder Community Steering Council identified, adapted, and/or designed survey items which were reviewed and then content validated by community members with lived experience.

Results:

The final survey instrument spans the perinatal care experience, from preconception to early parenthood, and includes items to capture experiences of care across different pregnancy roles (eg, pregnant person, partner/co-parent, intended parent using surrogacy) and pregnancy outcomes (eg, live birth, stillbirth, miscarriage, and abortion). Three validated measures of respectful perinatal care are included, as well as measures to assess experiences of racism, discrimination, and bias across intersections of identity.

Discussion and Conclusions:

By centering diverse perspectives in the review process, the Birth Includes Us instrument is the first survey to assess the range of experiences within LGBTQ2S+ communities. This instrument is ready for implementation in studies that seek to examine geographic and identity-based perinatal health outcomes and care experiences among LGBTQ2S+ people.

Keywords: community-based participatory research, LGBTQ persons, pregnancy, respectful care

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Limited research exists describing how lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, two-spirit, and other sexual and gender-minoritized (LGBTQ2S+) communities experience perinatal health care and pregnancy-related outcomes. From what is known, cisgender sexual minority women experience higher rates of miscarriage, stillbirth, low-birthweight infants, preterm birth, and other adverse birth outcomes compared with cisgender heterosexual women.1,2 Pregnancy and birth outcomes research on transgender and gender nonconforming individuals, including two-spirit and intersex people, are largely absent from the literature, with the existing evidence limited in scope and power to detect differences in groups.2 Qualitative evidence on pregnancy care experiences is more available, mainly among cisgender lesbian women,3–5 bisexual women,6,7 and transgender and gender nonconforming individuals8; all reporting experiences rooted in sexual and gender identity-related stigma and discrimination including bias, disrespect, and mistreatment. In addition, very little is known about nongestational LGBTQ2S+ parents’ experiences, with the evidence available showing that nongestational parents experience stress, uncertainty, and a lack of social support when their parental role is not socially or legally validated.9,10 There is a significant need to explore both pregnancy-related outcomes and experiences of respectful perinatal care for all identities within the LGBTQ2S+ continuum.

Respectful maternity (perinatal) care, defined as care that maintains dignity, privacy, confidentiality, and prioritizes freedom from harm and mistreatment, informed choice, and continuous support during pregnancy and childbirth,11 has been a focus within the global health literature as a mitigator of maternal mortality and morbidity disparities.12 Several studies have developed measures to quantify respectful or person-centered care,13–17 with many finding that experiences of disrespect, lack of autonomy and decision-making power, and mistreatment occur most frequently among racially marginalized communities.14,15,18 Experiences of stigma and discrimination have been documented for LGBTQ2S+ families seeking perinatal care in qualitative research,3,4,5,19 but larger scale measurement of respectful perinatal care have been largely absent for this population. Given the well-documented intersectional effects of racism and other sources of stigma and oppression on health outcomes,20–22 LGBTQ2S+ communities and particularly LGBTQ2S+ communities of color are likely to experience the greatest risk of adverse perinatal outcomes.

To our knowledge, no studies have explored how experiences with preconception, pregnancy, birth, and postpartum care differ for LGBTQ2S+ communities, in particular LGBTQ2S+ communities of color. This failure to examine LGBTQ2S+ experiences of respectful perinatal care represents a profound gap in perinatal health research, given the known disparities in perinatal outcomes1,2 and the established relationships between respectful care and improved outcomes for other groups.15,23 To improve perinatal outcomes for LGBTQ2S+ people, we need to understand their lived experiences of perinatal care, including what they identify as respectful care.

The Birth Place Lab at the University of British Columbia spearheaded the Giving Voice to Mothers (GVTM) survey in 2016 to capture respectful maternity care in the United States.15 During the course of the GVTM study, the GVTM Community Steering Council identified a need for a survey that specifically addressed experiences of care for LGBTQ2S+ populations, which sparked the Birth Includes Us survey development process. Beginning in 2018, a team of LGBTQ2S+ researchers, in collaboration with the Birth Place Lab researchers, convened a Community Steering Council and the Birth Includes Us study was initiated with the intention to center the lived experience of LGBTQ2S+ populations. In this article, we describe the community-based participatory methods used to develop the Birth Includes Us survey.

2 |. METHODS

The Birth Includes Us survey instrument was co-created with community partners to ensure that the survey not only captured relevant information on the entire perinatal care journey of LGBTQ2S+ populations (eg, preconception and family building, loss experiences, nongestational parent roles, and experiences), but also to ensure that people across multiple sexual, gender, and racial identities can see themselves represented in the survey. Utilizing established methods used to guide community participatory survey development,13–15 the following steps were undertaken: convening the Community Steering Council, item generation and survey construction including adaptation and/or design of new items, expert review of the draft survey, content validation with prospective participants, and revisions leading to the final instrument. The study was reviewed and approved by the University of Washignton Institutional Review Board.

2.1 |. Convening the Community Steering Council

The Birth Includes Us Community Steering Council consists of stakeholders within LGBTQ2S+ communities who experienced and/or engaged in perinatal health services as a patient, clinician, researcher, and/or community member (Table 1). To identify individuals with a representative variety of experiences and expertise, the PI and co-investigators nominated and selected members through an intentional networking process. Ultimately, the Community Steering Council included 13 members, representing both the United States and Canada, all of whom identity within one or more of the LGBTQ2S+ communities (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Demographics of Steering Council (N = 13)

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Black | 2 (15) |

| Black/Hispanic | 1 (8) |

| Black/Jamaican | 1 (8) |

| Latinx | 1 (8) |

| White | 7 (54) |

| White/Jewish | 1 (8) |

| Gender identity | |

| Cisgender woman | 6 (46) |

| Cisgender man | 1 (8) |

| Nonbinary | 3 (23) |

| Gender nonconforming/Nonbinary | 1 (8) |

| Queer/Nonbinary | 1 (8) |

| Genderqueer | 1 (8) |

| Sexual identity | |

| Bisexual | 1 (8) |

| Gay | 1 (8) |

| Lesbian | 1 (8) |

| Pansexual | 1 (8) |

| Queer | 8 (62) |

| Queer/Demisexual | 1 (8) |

| Professional/personal role | |

| Health care practitioner | 6 (46) |

| Personal lived experience | 9 (69) |

| Policy/advocacy | 3 (23) |

| Research/education | 9 (69) |

| Country of Residence | |

| Canada | 4 (31) |

| United States | 9 (69) |

Totals do not add to 100% because of the ability to identify with multiple options.

Inaugural members of the Community Steering Council met with the research team in January 2019 to identify priority topics, domains, and the baseline structure for an online survey. During the survey creation period (2019–2022), the Community Steering Council met approximately four times per year. The Community Steering Council functions as the decision-making body for the study and therefore has been involved in all steps of the research process. Given the power hierarchies that exist between the research team and Community Steering Council, decisions were made by consensus among the Community Steering Council members, with input from the research team as needed to facilitate any disputes. Upon completion of data collection with this instrument, the Community Steering Council will guide analyses, advise on interpretation and on ways to reduce potential harm, and direct dissemination efforts to ensure that all findings from the study are communicated to the community in equitable and respectful ways.

2.2 |. Item generation and survey construction

With guidance from the Community Steering Council, the initial survey instrument was developed over a 2-year period (1/2019–12/2020). We began by adapting the wording of survey items from the Giving Voice to Mothers (GVTM) survey15 and the subsequent version applied to Canada, the Research Examining the Stories of Pregnancy and Childbearing in Canada Today (RESPCCT) survey24 to resonate with LGBTQ2S+ individuals who may be in monogamous, polyamorous, and multiple co-parent family structures. Items retained from the previous instruments assess sociodemographic, clinical, and experiential factors across 12 domains of respectful care.25

The Community Steering Council applied theoretical and practical understandings of LGBTQ2S+ pregnancy experiences to ensure all appropriate constructs and domains were included. For example, based on feedback from the Community Steering Council, the Birth Includes Us survey was expanded to consider or include the following: (a) extended time frame, including all pregnancy experiences within a 10-year period; (b) expansive view on family building process, including diverse conception modalities like assisted reproduction; (c) multiplicity of pregnancy roles a person may experience, as a pregnant person, as partner/co-parent to a pregnant person, or as an intended parent using surrogacy; (d) expansive pregnancy experiences, including live birth, stillbirth, miscarriage, abortion; and (e) intersectional framing, to better capture the multifaceted impact of racism and other forms of oppression on gendered experiences of pregnancy care for LGBTQ2S+ people of color. All substantive decisions were reviewed and discussed with the Community Steering Council throughout the iterative development process.

2.3 |. Expert review

In November 2020, members of the Community Steering Council were invited to conduct a comprehensive expert review of the entire survey before content validation by prospective participants. Five expert reviewers provided input through narrative comments on an e-review form. Suggested changes were collated by the research team, and minor changes (such as word changes or additional response options) were implemented immediately. Substantive changes requiring discussion were brought forward to the Community Steering Council for discussion and approval before revising the survey.

2.4 |. Content validation

Given the highly marginalized experiences of many members of the LGBTQ2S+ community, we chose to use a method for content validation that did not require cognitive interviews where there could be a noticeable power differential between researcher and participant.26–28 Instead, we used a modality to allow confidential review and feedback from validators.27,28 Between December 2020 and May 2021, the study team recruited 30 content validators. Inclusion criteria for content validators were (a) self-identified as LGBTQ2S+; (b) experienced pregnancy care in the United States or Canada; (c) experienced a pregnancy as either a pregnant person, a partner/co-parent of a pregnant person, or as an intended parent using surrogacy; and (c) had at least one pregnancy experience in the last 10 years. Efforts were made to have as representative a sample of content validators across all pathways and types of experiences by using targeted recruitment strategies including social media avenues, respondent-driven sampling, and through connections with the Community Steering Council.

Content validators who consented to participate received a link to the online Birth Includes Us survey draft, in which each question was numbered and correlated to specific questions on a feedback tracking form for ease of reporting, and a list of questions to consider while reviewing the survey (Appendix S1). Participants assessed the inclusivity of language and accessibility of the survey and commented on the importance, relevance, and clarity of each question to their own individual context and to their community.26 Given the complexity and length of the survey, and that the majority of questions were extensively content validated as part of the GVTM and RESPCCT survey development,15,24 we did not require validators to evaluate each question but rather to highlight only those items that needed changes or were not relevant or important to their communities. In an effort to minimize harm, content validators were invited to improve or edit questions that may involve recalling difficult, sad, or uncomfortable memories. In addition to providing feedback specific to survey items, they completed a short online survey (Appendix S2) on clarity of the introduction and consent form, whether online survey tool was easy to navigate and to identify any missing items or domains. Their contributions were acknowledged with a $100 gift card.

The research team then reviewed feedback, made changes that were straightforward to the survey, and brought remaining questions that required further consideration to a workgroup of Community Steering Council members. Feedback was used to fine-tune the language used and to modify the internal logic of the survey.

2.5 |. Final survey revisions

Following content validation, the full Community Steering Council reviewed the edits. The Council’s most significant recommendation for this phase was to shorten the survey to facilitate participant completion. The research team conducted one final review to remove or consolidate questions. To mitigate the potential loss of specificity, we added new open-text questions for participants to describe experiences in greater detail. Finally, the Birth Place Lab reviewed the survey before launching the pilot study to ensure that the final wording would be valid and acceptable throughout both the United States and Canada.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Expert reviews

Five Community Steering Council members independently completed the expert review. The expert reviewers consisted of two researchers in LGBTQ2S+ health, two health care practitioner, and a community member with lived experience. Feedback predominantly focused on the use of inclusive and consistent terminology (ie, using LGBTQ2S+ for community designation, branching logic to ensure correct terms were used for United States versus Canada), ensuring representation of as many LGBTQ2S+ identities and experiences as possible, specific feedback based on reviewer’s expertise (ie, abortion questions, surrogacy questions), and grammar/syntax/punctuation issues. Three topic areas were brought back to the Community Steering Council for review: (a) whether to include the intended parents through surrogacy pathways, (b) whether to include questions asking for body organs to determine capacity for pregnancy, and (c) whether to include attempts for pregnancy that are not successful (ie, infertility). The Community Steering Council recommended deferring final decisions on these topics until after the content validation phase.

3.2 |. Content validation

The research team recruited 30 individuals who met study criteria (ie, LGBTQ2S+, pregnancy experience in past 10 years, living in United States or Canada) to an expert content validation panel28 (Table 2). The content validators provided descriptive feedback on survey format, individual items, and groups of items. Table 3 provides an account of the types of changes made to the survey from this phase.

TABLE 2.

Self-identified demographics of content validators (n = 30)

| Number (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Race | |

| Asian | 1 (3) |

| Black | 2 (7) |

| Black/Latinx | 1 (3) |

| Indigenous | 3 (10) |

| Latinx | 1 (3) |

| Latinx/Indigenous | 1 (3) |

| Middle Eastern | 1 (3) |

| Romani/Mizrahi | 1 (3) |

| White | 19 (63) |

| Gender identity | |

| Cisgender woman | 10 (33) |

| Cisgender man | 3 (10) |

| Nonbinary | 3 (10) |

| Gender nonconforming | 2 (7) |

| Gender nonconforming/Nonbinary | 1 (3) |

| Trans/Nonbinary | 2 (7) |

| Trans-masculine | 5 (17) |

| Two-Spirit | 1 (3) |

| Pangender | 1 (3) |

| Agender | 1 (3) |

| Anti-gender | 1 (3) |

| Sexual identity | |

| Bisexual | 1 (3) |

| Gay | 5 (17) |

| Lesbian/queer | 3 (10) |

| Pansexual | 1 (3) |

| Queer | 20 (67) |

| Country of Residence | |

| Canada | 11 (37) |

| United States | 19 (63) |

Totals do not equal 100% because of the ability to identify with multiple options.

TABLE 3.

Content validation of revisions and changes

| Type of change | Number of changes |

|---|---|

| Wording or grammatical changes to the response options | 27 |

| Wording or grammatical changes to the question stem | 26 |

| Changes to skip or branching logic | 26 |

| Changes to questions from GVTM or RESPCCT surveys to make more gender inclusive | 16 |

| Addition of examples or descriptors with questions for clarity | 13 |

| Addition of “N/A” or “I do not know” response options | 12 |

| Changes to acronyms or terms for consistency (eg, LGBTQ2S+) | 9 |

| Branching of questions to reflect United States and Canadian differences in context | 6 |

| Changes from single multiple choice option to “check all that apply” | 5 |

| Addition of open-response/free text questions | 5 |

| Addition of option to choose provider type before respectful perinatal care questions | 2 |

| Addition of COVID-19 impacts to experiences | 2 |

Eleven questions within four topic areas required consultation with the Steering Council over the 9-month content validation phase. One of these topics focused on increasing the specificity of the type of provider a respondent could attribute their experiences to; to do this, multiple questions were introduced with the prompt “Your answers in this section describe your conversations or experiences with a…[physician, midwife, nurse practitioner, nurse, N/A—I did not interact with a provider]”. A second topic focused on whether sex assigned at birth and/or reproductive anatomy was necessary information to gather for determining capacity for pregnancy. The Steering Council decided that including identification of reproductive anatomy was not necessary and likely would be triggering to participants, and so an alternate question was included instead: “Do you have or have you ever had the physical ability to be pregnant?” in conjunction with sex assigned at birth. Multiple questions were identified as unnecessarily triggering to participants carrying various identities; these questions were reviewed to determine if they were important to include, and if so, preparation statements or trigger warnings were added ahead of these questions. Lastly, the context of disseminating this survey across two countries during years that included significant social and political events that largely affected marginalized communities (eg, COVID-19 pandemic and anti-Black racism) became apparent during the content validation phase. Multiple questions were reviewed and revised by the Steering Council to reflect the differing experiences of discrimination between racialized participants in Canada and the United States.

3.3 |. Final survey instrument

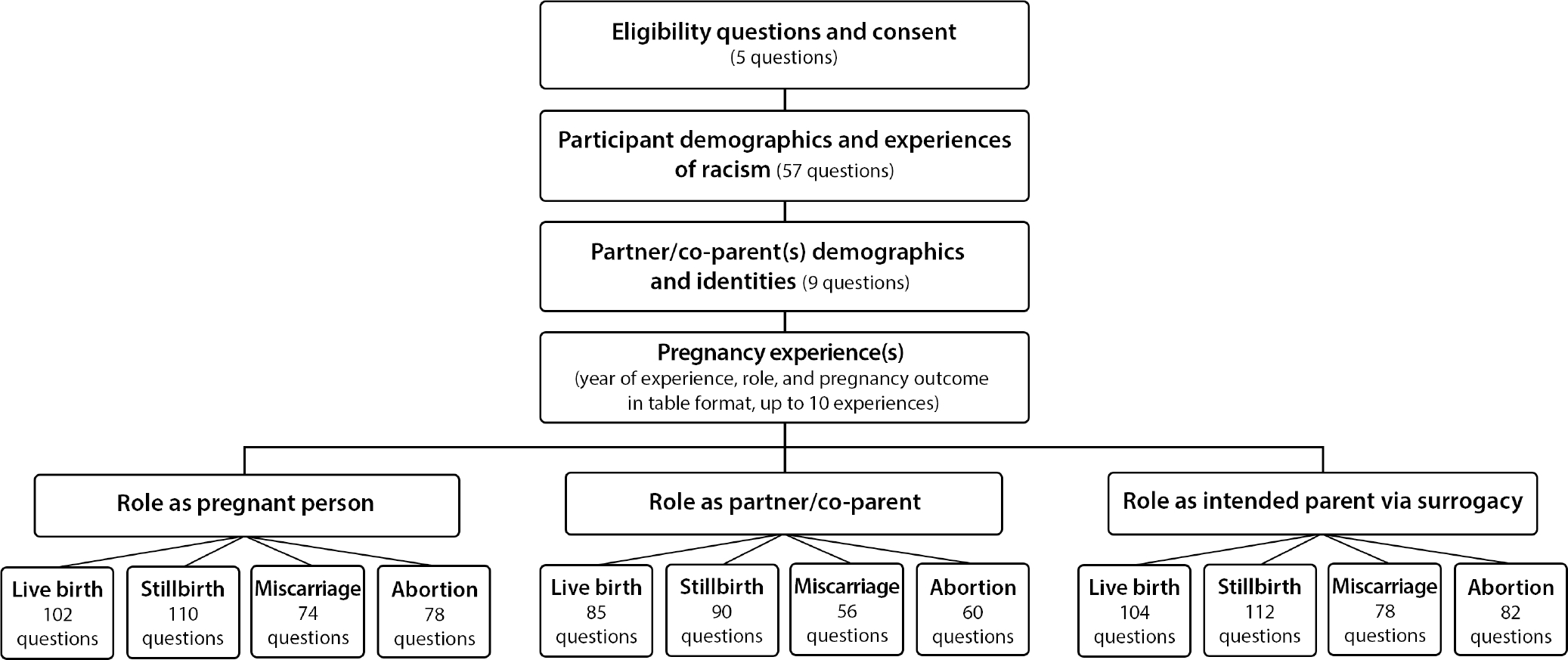

The final survey instrument consists of three main sections that all participants complete: First, determination of study eligibility and consent and capture of participant identities, demographics, and experiences with racism/discrimination; second, capture of partner/co-parent identities; and third, questions to identify year and type of experience, (live birth, miscarriage, abortion, and stillbirth), and the individual’s role in the pregnancy (pregnant person, partner/co-parent, and intended parent using surrogacy) (Figure 1). In addition, participants can link their survey responses for each listed pregnancy experience to a partner/co-parent by providing an e-mail, allowing for analysis on different perspectives of the same pregnancy experience.

FIGURE 1.

Final survey configuration

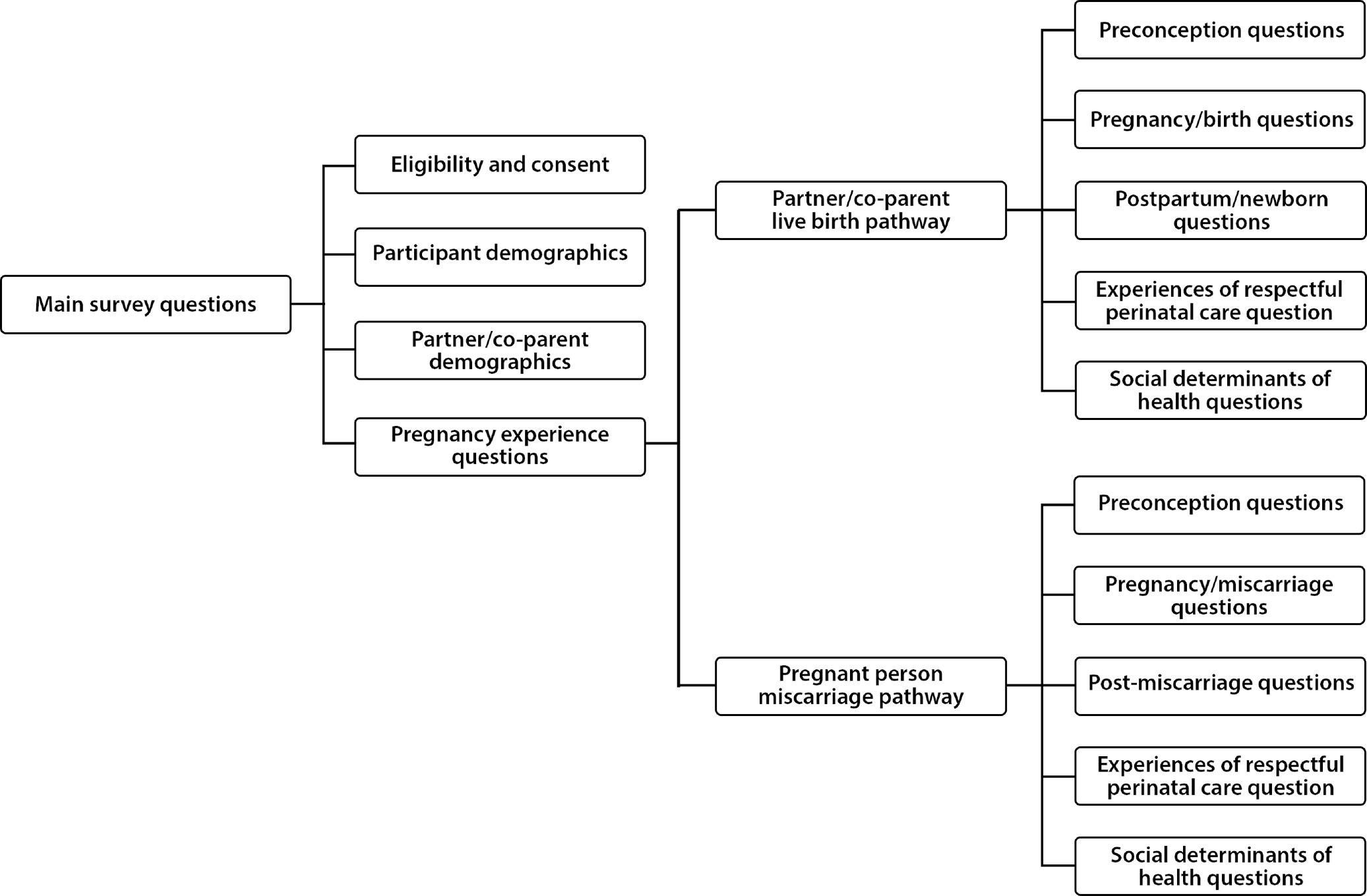

Using the information provided in the third section, the survey then branches into 12 different pathways depending on the type of, and relation to, each pregnancy experience. For example, if a person experienced a live birth as a partner/co-parent and a miscarriage as a pregnant person, they would be directed to complete two pathways that match those outcomes and roles (Figure 2). In each pathway, questions pertaining to preconception, pregnancy, birth or other outcome, and postpartum/postoutcome were included. In addition, interactions with health care practitioners regarding respect, autonomy, decision-making, and mistreatment are captured with adapted versions of the validated Mothers’ Autonomy in Decision-Making (MADM) scale,13 Mothers on Respect Index (MORi),14 and Mistreatment Index (MIST).15 Finally, questions about social determinants of health are included, including access to resources and services.

FIGURE 2.

Example of survey progression based on experience and role. Exemplar—A participant who experienced a live birth as a partner/co-parent and a miscarriage as a pregnant person

4 |. DISCUSSION

Over a 2-year period using a community-based participatory research approach, a multi-national team of LGBTQ2S+ researchers, stakeholders, and allies developed the Birth Includes Us survey. The research team collaborated with a Community Steering Council to inform major structural and content changes to the survey. An extensive, community-driven development process gave the research team the opportunity to review each pathway from multiple perspectives, making the survey inclusive of diverse gender and sexual minority populations who experience perinatal care, including polyamorous and single-by-choice parents who are often excluded in research. Ultimately, the Birth Includes Us survey instrument uniquely captures the experiences of pregnant people, their partners/co-parents, and/or intended parents using a surrogate who experiences any form of pregnancy-related outcome (live birth, abortion, miscarriage, and stillbirth).

The Birth Includes Us survey fills a significant gap within the perinatal care literature by addressing the intersectional experiences of discrimination among LGBTQ2S+ individuals and families. There is a growing body of research on the perinatal health outcomes and experiences of some sexual and gender minority identity groups, notably lesbian nongestational mothers,9,10 queer and bisexual cisgender women,29,30 and transgender men or gender-minoritized people.2,8,31,32 Limited research explores the experiences of BIPOC cisgender and transgender lesbian women33 and cisgender gay men using surrogacy.34,35 Furthermore, although recently published data address abortion care for gender-minoritized individuals,36,37 there is still a deficit of research documenting LGBTQ2S+ experiences of stillbirth or miscarriage. The RESPCCT and GVTM surveys from the Birth Place Lab address the intersections of pregnancy and/or childbearing and of having a racialized experience, yet these instruments do not sufficiently detail the experience of LGBTQ2S+ parents and intersections of oppression experienced by many within these communities. The Birth Includes Us survey builds on these existing studies by encompassing all the multifaceted ways in which LGBTQ2S+ parents create their families and experience pregnancy care. In addition, the instrument assesses the complex medical and legal steps of the preconception and birthing process that are specific to LGBTQ2S+ individuals. Notable also is that this survey captures experiences based on role and pregnancy outcome, and allows for disaggregated analysis based on gender, anatomy/capacity for pregnancy, and sexual identity, which has not been done to our knowledge in the literature. This comprehensive survey data will allow for greater specificity and flexibility in analyses to inform and support the development of interventions to improve care for the myriad forms of LGBTQ2S+ families.

Meeting the goal of building an authentically inclusive survey proved complex. Throughout the process, the research team and Community Steering Council recognized new ways that survey questions could be re-worded or the branching logic altered to represent the experiences of the LGBTQ2S+ community, which in turn led to substantial edits to the structure of the survey late into content validation phase. Prior research on pregnancy outcomes among LGBTQ2S+ people is not inclusive of all birth outcomes, often does not consider sexual orientation and gender identity as separate constructs, and does not include the experiences of all partners or intended parents. Hence, the Birth Includes Us team sought to create a survey that would give participants the option to describe nuanced experiences often excluded from prior research. The research team also accepted that no number of revisions could accurately capture the breadth of experience within the LGBTQ2S+ community, so they added open-response text options at the close of each birth phase (preconception, pregnancy, and birth/pregnancy outcome) for participants to contextualize their responses. Members of the Steering Council and Birth Place Lab provided regular insight from past surveys on how to structure response options and branching to facilitate organization and analysis of a data set of this size and complexity.

Developing a survey for two different national contexts proved challenging, both in terms of respective intersectional identities and differing political climates. It was essential to have the survey represent specific historical harms within racial and politically defined communities of both nations, as this history is intertwined with the history of LGBTQ2S+ people. Canada and the United States are at different and unique stages with respect to historical reparations for racist acts against their Indigenous, First Nations, Black, and other racialized communities, all of which needed representation within the survey.

4.1 |. Strengths/limitations

A major strength of the Birth Includes Us survey is the explicit inclusion of the unique and dynamic ways pregnancies are experienced by LGBTQ2S+ families, including different parental, partner, and gestational roles, outcomes, and intersections of identities. In addition, this survey specifies understudied aspects of the experiences of family making, including legal and social structures that affect experiences of respect and quality of care.

There are three known limitations of this research: length, inclusion limitations, and language. (a) To develop an instrument in which all members of the LGBTQ2S+ community would feel included, the research team had to vary the length of each pathway resulting in a heavy survey burden for some participants. Individuals who had more interactions with health care—for example, those who used assisted reproductive care for conception—have more questions to answer. The length of the survey may also hamper robust participation and recruitment of respondents with limited resources or bandwidth. (b) We were unable to identify Indigenous/First Nations/Two-Spirit individuals for the Community Steering Council, which was a significant limitation in representation. However, the surveys that Birth Includes Us was adapted from, the GVTM and RESPCCT surveys, did extensive content validation of items within these communities, suggesting that the majority of items adapted for the Birth Includes Us survey instrument may appropriately represent the needs of these communities. Representation from the intersex community is also notably absent, for which we used the limited literature on intersex experiences to ensure as much inclusion as possible within the survey questions. In addition, the Steering Council did not have trans-feminine representation; however, there was representation within the content validation phase. (c) The research team did not have funding and resources to provide translation of the survey; therefore, the Birth Includes Us survey was not accessible to LGBTQ2S+ people who speak other languages. In future phases, the research team will have this survey translated to reflect other major languages in the United States and Canada. Pilot testing is underway and will assess the feasibility of online recruitment modalities for LGBTQ2S+ family-building communities, construct validity of three measures assessing domains of respectful perinatal care (autonomy, respect, and mistreatment), and sample size calculation for comprehensive disaggregation by sexual and gender identity. Full implementation of the survey will be conducted to capture population-level estimates, with intersectional analyses to assess relationships among racial, sexual, and gender identities as it relates to respectful perinatal care. The adapted instruments measuring autonomy, decision-making, respect, and mistreatment will be made available after validation for future research.

4.2 |. Conclusion

Birth Includes Us is the first large-scale study to explore the pregnancy, birth, and family-building experiences of the LGBTQ2S+ community in the United States and Canada. Our overarching conclusion is that a community participatory approach to survey development, with input from a heterogeneity of professions, experiences, and intersections of identity, resulted in a ground-breaking and inclusive tool to capture perinatal experiences of care. A collaboration of predominately LGBTQ2S+ researchers along with a Steering Council of community stakeholders made the completion of this survey possible, and their combined expertise and lived experiences created an instrument that intends to encompass a wide variety of experiences within pregnancy currently underrepresented in research. Full implementation of the Birth Includes Us survey will identify which identities and geographies are most under-resourced and inform directed policy action to address health disparities such as perinatal mortality and morbidity.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the time, energy, inspiration, and leadership within the Birth Includes Us Community Steering Council, for which this study would not have been possible. We would like to also thank everyone within the queer and trans communities who put time into making sure the Birth Includes Us survey was inclusive and representative of the experiences that are so often not told through research.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported, in part, by the University of Washington Research and Intramural Research Program, the University of Washington Royalty Research Fund, and the University of Washington/University of British Columbia Collaborative Research Mobility Award. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

This paper is funded by the Women’s Reproductive Health Research program by the NICHD. My grant # is: 2K12HD001262.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Everett BG, Kominiarek MA, Mollborn S, Adkins DE, Hughes TL. Sexual orientation disparities in pregnancy and infant outcomes. Matern Child Health J. 2018;23:72–81. doi: 10.1007/s10995-018-2595-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leonard SA, Berrahou I, Zhang A, Monseur B, Main EK, Obedin-Maliver J. Sexual and/or gender minority disparities in obstetrical and birth outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226(6):846.e1–846.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.02.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dahl B, Fylkesnes AM, Sørlie V, Malterud K. Lesbian women’s experiences with healthcare providers in the birthing context: a meta-ethnography. Midwifery. 2013;29(6):674–681. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2012.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gregg I The health care experiences of lesbian women be-coming mothers. Nurs Womens Health. 2018;22(1):40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.nwh.2017.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malmquist A, Nelson KZ. Efforts to maintain a ‘just great’ story: lesbian parents’ talk about encounters with professionals in fertility clinics and maternal and child healthcare services. Fem Psychol. 2014;24(1):56–73. doi: 10.1177/0959353513487532 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ross LE, Siegel A, Dobinson C, Epstein R, Steele LS. ‘I don’t want to turn totally invisible’: mental health, stressors, and supports among bisexual women during the perinatal period. J GLBT Fam Stud. 2012;8(2):137–154. doi: 10.1080/1550428X.2012.660791 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Januwalla AA, Goldberg AE, Flanders CE, Yudin MH, Ross LE. Reproductive and pregnancy experiences of diverse sexual minority women: a descriptive exploratory study. Matern Child Health J. 2019;23(8):1071–1078. doi: 10.1007/s10995-019-02741-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellis SA, Wojnar DM, Pettinato M. Conception, pregnancy, and birth experiences of male and gender variant gestational parents: it’s how we could have a family. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2015;60(1):62–6 9. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wojnar DM, Katzenmeyer A. Experiences of preconception, pregnancy, and new motherhood for lesbian nonbiological mothers. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2014;43(1):50–60. doi: 10.1111/1552-6909.12270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abelsohn KA, Epstein R, Ross LE. Celebrating the ‘other’ parent: mental health and wellness of expecting lesbian, bisexual, and queer non-birth parents. J Gay Lesbian Mental Health. 2013;17(4):387–405. doi: 10.1080/19359705.2013.771808 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bohren MA, Tunçalp Ö, Miller S. Transforming intrapartum care: respectful maternity care. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;67:113–126. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2020.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. Standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities. 2016.

- 13.Vedam S, Stoll K, Martin K, et al. The Mother’s Autonomy in Decision Making (MADM) scale: patient-led development and psychometric testing of a new instrument to evaluate experience of maternity care. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0171804. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vedam S, Stoll K, Rubashkin N, et al. The Mothers on Respect (MOR) index: measuring quality, safety, and human rights in childbirth. SSM Popul Health. 2017;3:201–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vedam S, Stoll K, Taiwo TK, et al. The Giving Voice to Mothers study: inequity and mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth in the United States. Reprod Health. 2019;16(1):77. doi: 10.1186/s12978-019-0729-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Afulani PA, Altman MR, Castillo E, et al. Development of the person-centered prenatal care scale for people of color. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:427.e1–427.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.04.216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Afulani PA, Altman MR, Castillo E, et al. Adaptation of the person-centered maternity care scale for people of color in the United States. Women’s Health Issues. 2022;32(4):352–361. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2022.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vedam S, Stoll K, McRae DN, et al. Patient-led decision making: measuring autonomy and respect in Canadian maternity care. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;102:586–594. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2018.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ross LE, Tarasoff LA, Anderson S, et al. Sexual and gender minority peoples’ recommendations for assisted human reproduction services. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2014;36(2):146–153. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(15)30661-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alhusen JL, Bower KM, Epstein E, Sharps P. Racial discrimination and adverse birth outcomes: an integrative review. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2016;61(6):707–720. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shavers VL, Fagan P, Jones D, et al. The state of research on racial/ethnic discrimination in the receipt of health care. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):953–966. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2012.300773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.White VanGompel E, Lai JS, Davis DA, et al. Psychometric validation of a patient-reported experience measure of obstetric racism© (The PREM-OB Scale™ suite). Birth. 2022;49:514–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kennedy HP, Cheyney M, Dahlen HG, et al. Asking different questions: a call to action for research to improve the quality of care for every woman, every child. Birth. 2018;45(3):222–231. doi: 10.1111/birt.12361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vedam S Research examining the stories of pregnancy and childbearing in Canada today (RESPCCT). 2022. https://www.birthplacelab.org/respcct/

- 25.Clark E, Vedam S, McLean A, Stoll K, Lo W, Hall WA. Using the Delphi method to validate indicators of respectful maternity care for high resource countries. J Nurs Meas. 2022. doi: 10.1891/jnm-2021-0030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing Research: Principles and Methods. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schilling LS, Dixon JK, Knafl KA, Grey M, Ives B, Lynn MR. Determining content validity of a self-report instrument for adolescents using a heterogeneous expert panel. Nurs Res. 2007;56(5):361–366. doi: 10.1097/01.nnr.0000289505.30037.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Polit DF, Beck CT. The content validity index: are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29(5):489–497. doi: 10.1002/nur.20147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fredericks E, Harbin A, Baker K. Being (in)visible in the clinic: a qualitative study of queer, lesbian, and bisexual women’s health care experiences in Eastern Canada. Health Care Women Int. 2017;38(4):394–408. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2016.1213264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baker K, Beagan B. Making assumptions, making space: an anthropological critique of cultural competency and its relevance to queer patients. Med Anthropol Q. 2014;28(4):578–598. doi: 10.1111/maq.12129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoffkling A, Obedin-Maliver J, Sevelius J. From erasure to opportunity: a qualitative study of the experiences of transgender men around pregnancy and recommendations for providers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(Suppl 2):332. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1491-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Obedin-Maliver J, Makadon HJ. Transgender men and pregnancy. Obstet Med. 2016;9(1):4–8. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stevens PE. The experiences of lesbians of color in health care encounters. J Lesbian Stud. 1998;2(1):77–94. doi: 10.1300/J155v02n01_06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smietana M Procreative consciousness in a global market: gay men’s paths to surrogacy in the USA. Reprod Biomed Soc Online. 2018;7:101–1 11. doi: 10.1016/j.rbms.2019.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Russell C Rights-holders or refugees? Do gay men need reproductive justice? Reprod Biomed Soc Online. 2018;7:131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.rbms.2018.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moseson H, Fix L, Ragosta S, et al. Abortion experiences and preferences of transgender, nonbinary, and genderexpansive people in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224(4):376.e1–376.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.09.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moseson H, Fix L, Gerdts C, et al. Abortion attempts without clinical supervision among transgender, nonbinary and genderexpansive people in the United States. BMJ Sex Reprod Health. 2022;48(e1):e22–e30. doi: 10.1136/bmjsrh-2020-200966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.