Abstract

Objectives:

Despite the significant mental health challenges and unique treatment needs of transgender and gender diverse (TGD) youth, research on the acceptability of evidence-based treatments for these youth is limited. To address this gap, the current study explored the perceived relevance of Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) for high-risk TGD youth.

Methods:

Qualitative data was collected from six focus group discussions with a purposive sample of 21 TGD youth aged 18 – 25 years old who endorsed a history of depression, suicidality, or self-harm and individual interviews with 10 mental health providers with prior DBT and TGD client experience. The data were analyzed inductively using thematic content analysis.

Results:

The results highlighted the perceived relevance of DBT in targeting chronic and acute stressors, some of which are unique to TGD youth such as issues related to gender dysphoria, hormone-related treatment, and gender identity. Possible areas for treatment modifications including the adaptation of body awareness exercises and physiological-related coping techniques for youth experiencing gender dysphoria and the reinforcement of self-care skills were identified. While interpersonal effectiveness skills were acknowledged as important, providers highlighted a need to prioritize safety over the practice of these skills. This is because TGD youth often experience more hostile and prejudiced interpersonal experiences than their cisgender peers.

Conclusion:

The study’s findings shed light on previously unexplored perspectives of TGD youth and providers on the perceived relevance of DBT and provide DBT treatment providers and implementation researchers with some critical issues to consider when working with high-risk TGD youth.

Keywords: transgender youth, gender diverse, dialectical behavior therapy, mental health intervention, qualitative

Background

Transgender and gender diverse (TGD) youth face significant and unique challenges that place them at an increased risk for depression, self-harm, and suicidality (Connolly et al., 2016; Taliaferro et al., 2019; Veale et al., 2017). Rates of depression are more than twice as high for TGD compared to cisgender youth (Reisner et al., 2015). TGD youth are more likely to endorse suicidal ideation and attempts (Greytak, 2009; Liu & Mustanski, 2012) and are almost twice as likely to have self-harmed compared to their cisgender peers (McDermott et al., 2018). Yet research on the effectiveness and acceptability of evidence-based mental health treatments for TGD youth remains limited (Budge et al., 2021; Pachankis, 2018).

Although most well-known for its application to the treatment of borderline personality disorder (BPD; Bloom et al., 2012; Kliem et al., 2010; Lynch et al., 2007), dialectical behavior therapy (DBT; Linehan, 1993) has also been proposed as a potentially appropriate treatment for TGD individuals struggling to cope with distress related to pervasive invalidation and discrimination of their gender diversity (Sloan et al., 2017). DBT conceptualizes emotion dysregulation, suicide risk, and self-harm as problems related to skills deficits arising from exposure to invalidating environments and underlying biological vulnerabilities (Linehan & Wilks, 2015). It is thought to be particularly relevant for TGD youth at risk for depression, suicidality, and self-harm because it explicitly addresses distress arising from chronic environmental and self-invalidation (Sloan et al., 2017). Many TGD youth are exposed to a sociocultural context that presumes sex and gender to be indistinguishable and binary (male/female). This can be invalidating for TGD youth as it marginalizes and negates diverse gender identity and expression (Oransky et al., 2019; Sloan et al., 2017). Experiences of invalidation and related distress, especially during critical developmental years, can lead to considerable emotional and behavioral dysregulation in TGD youth (Fraser et al., 2018; Villarreal et al., 2021).

One way that DBT may address problems faced by TGD youth is through the development of skills in the domains of mindfulness, distress tolerance, emotion regulation, and interpersonal effectiveness, which emphasize the dialectic between acceptance and change (Skerven et al., 2019; Sloan et al., 2017). For example, interpersonal skills can help TGD youth effectively respond to invalidating situations, such as being misgendered at school, work, or home, while maintaining self-respect. Distress tolerance can help reduce suicidal and self-harm behaviors arising from crisis situations. Mindfulness and emotion regulation skills can help TGD youth identify, understand, and balance emotions in the context of chronic marginalization, such as living with nonaccepting family members. These skills can be used to directly target structural, enacted, and manifested stigma and allow TGD youth to develop and maintain an affirming identity, even within an invalidating environment (Skerven et al., 2019).

Although DBT appears to be a promising treatment for high-risk TGD youth in theory, empirical evidence for its acceptability is lacking. Understanding DBT’s perceived relevance for the needs of TGD youth is important because interventions that are tailored and consider a client’s specific beliefs, values, and life experiences can increase treatment engagement and produce better client outcomes (Berger & Mooney-Somers, 2016; Budge et al., 2017; Desrosiers et al., 2015; Little et al., 2018; Pachankis & Safren, 2019). To address this gap, the current study explored the perceived relevance of DBT from the perspectives of both high-risk TGD youth and mental health treatment providers, with the goal of identifying areas for modification that could enhance DBT’s uptake and effectiveness for TGD youth.

Methods

Design and Sample

Data was obtained from 21 TGD youth (53.6% identified as transgender male, 10.7% transgender female, and 32.1% gender non-binary; 75% identified as White, 5.0% Black/African-American, and 15% bi-racial) aged between 18 – 25 years old (Mage = 20.5) and 10 mental health treatment providers (90% female; Mage = 40.7; clinical experience range = 1 – 23 years). A convenience sample of TGD youth were recruited using TGD-relevant social media groups and targeted online advertising. They were included if they self-identified as TGD and had endorsed a history of depression, suicidal ideation, self-harm, or suicide intent. Providers were recruited via a DBT listserv and were included in the study if they had obtained at least a master’s degree and had experience providing mental health services in the community. All providers endorsed experience with DBT and working with TGD individuals. TGD youth received $30 for their participation; providers did not receive any compensation. Of the 27 TGD youth who expressed interest in the study and met study criteria during the screening process, six dropped out prior to participating in the focus group due to scheduling issues; there was no attrition among the providers. No repeat interviews were conducted. None of the participants had an established relationship with the researchers prior to study commencement. Research procedures were approved by the Stony Brook University Institutional Review Board. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist was used to guide the reporting of the study (see supporting material) (Tong et al., 2007).

Procedures

Data analyzed for this study was part of a broader project on mental health barriers to care for TGD youth. TGD youth were enrolled in one of six focus groups (3 – 5 participants) from June 2020 to July 2020. The discussions were facilitated online by authors 1 or 2 and co-facilitated by another research team member. The youth were introduced to the topic and the goals of the research project at the start of the focus group; this was followed by some general questions about personal challenges that may have influenced their mental health and help-seeking experiences. For the purposes of the current study, the youth were then presented with an overview of DBT and an explanation of each module and the related skills. After each module was explained, they were prompted to discuss their overall impressions of the relevance of each module and how useful the specific skills were for the challenges they experienced. On average, the focus groups were held for 90 minutes each and the provider interviews took no longer than 60 minutes. Providers were interviewed online by author 1 and/or author 2 using a semi-structured protocol from July 2020 to October 2020. They were asked about their experiences with treating TGD clients in general and with specific reference to DBT and how each DBT module could be modified to be more relevant to them. The interview guides were pilot tested with the first couple of focus groups and providers, but as no modifications were made, the data collected in the pilot process were included in the data analysis. No systematic fieldnotes were made by the research team. The focus groups and interviews were audio recorded, transcribed, and reviewed for accuracy prior to analysis.

Data Analysis

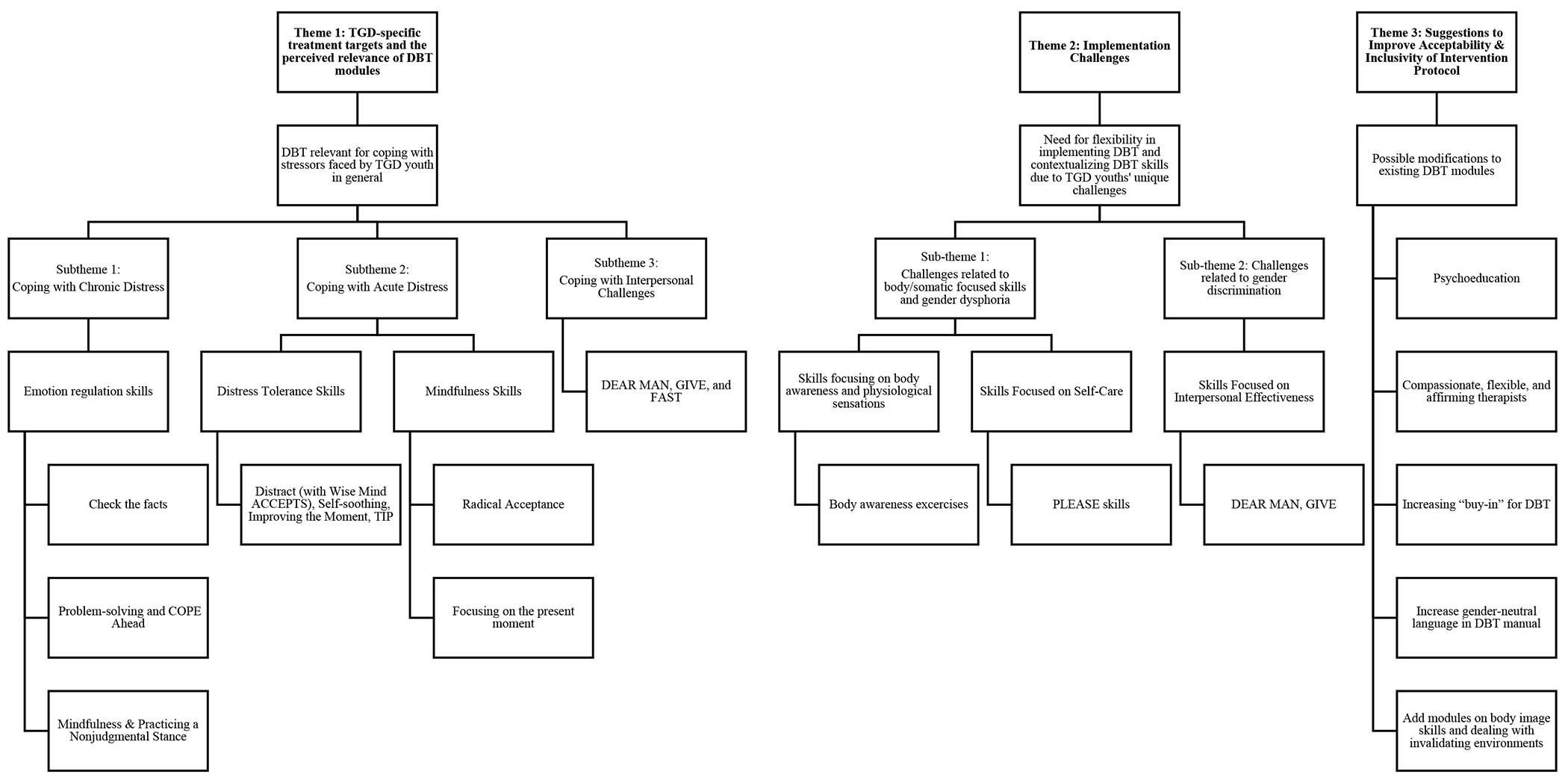

Data were inductively analyzed by three independent raters (authors 1, 2, and 4) using thematic content analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Microsoft Word and Excel programs were used to manage and code the data. All the TGD youths’ focus group transcripts were coded first before the providers’ interview data were analyzed. For both groups, the texts were thoroughly read once by authors 2 and 4 and segments of the text that were relevant to the research questions were highlighted (i.e., only responses to sections related to DBT were analyzed). Repeated ideas in the highlighted data were then systematically coded into categories that paraphrased or generalized the text (i.e., collapsed into broader themes) until thematic saturation was reached for each group. The list of categories derived for both groups were then reviewed by the authors 1 and 2 and – because the responses for both groups tended to revolve around specific DBT modules or skills – re-organized into a thematic framework focused on: (1) TGD-specific treatment needs and the applicability of DBT modules; (2) implementation challenges; and (3) suggestions to improve acceptability and inclusivity of intervention protocol. The final naming of the themes were derived in collaboration with the senior author and input the broader research team. Data collected from both groups were weighted similarly in terms of contribution to the final results. Discrepancies were resolved via discussion and transcript review until 100% agreement of the themes was reached. Figure 1 summarizes the final themes and subthemes in the form of a coding tree.

Figure 1.

Coding Tree

To reduce bias in coding, coding was completed by researchers of diverse backgrounds and experiences. Author 1 (Jacqueline Tilley) is a doctoral-level licensed clinical psychologist who, at the time of the study, was a post-doctoral fellow in an academic medical setting. She is trained in dialectical behavior therapy and has experience working with high-risk clients, with some exposure to TGD-related issues. Author 2 (Lucero Molina) has a bachelor’s degree in psychology and, at the time of the study, had been working in an academic medical setting as a research coordinator for several years. The author has broad knowledge of dialectical behavior therapy and TGD-related issues but not specific training in either topic. Both authors, who had key roles in designing the interview protocol, had an interest in improving the cultural sensitivity of mental health treatments as they both identify as belonging to marginalized groups. Author 4 (Aaradhana Natarajan) was an undergraduate student at the time of the study, with an interest in pre-medical sciences and psychiatry and, with minimal prior exposure to the research topics under investigation. Author 4 did not participate in the interview process or design of the study and therefore was relatively naive in terms of pre-conceptions about the topic and data for the purposes of analysis. The senior author (Brittain Mahaffey) who assisted with the overall framing of the data, is a licensed clinical psychologist and director of a Dialectical Behavior Therapy program at an academic medical setting. She has extensive experience treating high risk TGD individuals with CBT, DBT and mindfulness-based approaches.

The other team members who collaborated on research design and provided their insights on interpretation and writing included a licensed clinical psychologist who is an associate professor in psychiatry and behavioral health, a doctoral-level psychology research fellow, and a master’s level social work student. Across the research team, all the doctoral-level researchers had training in and experience delivering DBT to individuals who identified as LGBTQ+; and at least two had experience providing or supervising the provision of mental health treatment to TGD individuals. Two of the team members, one of whom was involved in aspects of data collection, endorsed having lived experience as an individual identifying as LGBTQ+; and at least one team member has a history of depression, suicidality or self-harm. All team members identified as cisgender and all, except one, identified as female.

Results

Theme 1: TGD-specific treatment needs and the perceived relevance of DBT modules

Overall, TGD participants and providers reported that the key DBT skills were relevant for coping with chronic and acute distress related to general stressors, such as feelings of loneliness, college-related stress, and interpersonal conflict, as well as challenges unique to TGD youth, such as gender dysphoria, invalidating contexts, and hormone-related treatment. TGD youth reported that learning these coping skills through DBT would be helpful because they often did not already possess the skills.

“Growing up with dysphoria… you spend the very early portions of your life feeling wrong and not knowing why… That’s before you even know what being trans [or gender dysphoria] is… At a very early age, you’re not focused on getting these skills, you’re focused on getting through the next day… As a teenager, if you told me all this, I would be like “what?… I could do that?” (TGD Youth #8, Transgender Male, 21 years old)

Subtheme 1: Coping with Chronic Distress

TGD youth reported that emotion regulation skills, such as check the facts, problem solving, and COPE Ahead, and mindfulness skills, such as practicing a non-judgmental stance, would be useful for managing day-to-day emotion dysregulation arising from gender dysphoria, environmental invalidation, and hormone replacement therapy.

“I already had a lot of mood swings [due to bipolar disorder]… but with adding the testosterone, that was something that needed a lot more work. I found that [working on emotion regulation skills with my therapist] to be very helpful, especially when I found myself with a lot more mood swings than normal due to HRT.” (TGD Youth, Transgender Male, 20 years old)

Check the Facts.

TGD youth reported that the ability to reframe their thoughts through skills, such as check the facts and challenging negative thoughts, was helpful, especially when they were confronted with invalidating circumstances and gender dysphoria-related ruminations.

“Because… you’re going to hate your body, it’s so easy to dig yourself into… a never ending pit of just being, ‘I’m never gonna look the way I want, people are never gonna see me the way I am, like I hate myself, why can’t I just be normal or accepted’ … you just go deeper and deeper and get stuck in that really negative thinking loop where you don’t see the positives… Learning to challenge those thoughts or having to rationalize it and say, ‘well, I’m having a better day today’ and ‘that’s not true that I’m not accepted by nobody. I have friends, I have… family’… Being able to pull up positive things, maybe ‘well I like this about myself, I like this about my physical appearance‘ or… ‘it’ll be better tomorrow, I’ll be feeling different in like, an hour‘ or… being able to like rationalize that it’s not going to be forever and you’re not always just going to constantly be feeling these bad things [is helpful].” (TGD Youth #20, Transgender Male, 22 years old)

Problem-solving and COPE Ahead.

TGD youth also highlighted that skills which help youth to problem solve around difficult situations and help then to mentally prepare them for anticipated stressful events, such as using public restrooms or interpersonal conflict, were useful for reducing persistent negative feelings.

“I’m really drawn to the coping ahead with anticipated problems piece. I feel like for me that would be one of the most important ones and… a lot of the issues that… trans people face in terms of… interpersonal conflict… can be… prepared for… like, if this is what someone says to me… this is going to be my response and … having the tools to… know how to address different scenarios that you might get as a trans person would be like, super, super helpful.” (TGD Youth #19, Gender Non-Binary, 20 years old)

Practicing a Nonjudgmental Stance.

Practicing a nonjudgmental stance was also identified as a relevant skill for TGD youth who struggle with gender dysphoria as it allowed them to reduce negative feelings about their appearance and show compassion towards themselves.

“With dysphoria I have a very warped perception of myself. I’ve gotten to the point where I can look at the situation a lot differently, less judgmentally… [and it has allowed me] to nip a few situations in the bud.” (TGD Youth #5, Transgender Female, 19 years old)

Subtheme 2: Coping with Acute Distress

Because TGD youth frequently experience invalidating environments that can lead to acute emotional distress, TGD youth and providers reported that distress tolerance and mindfulness skills can help them to cope and function better in their daily lives.

“I have really focused a lot on the distress tolerance skills for my trans clients… they are unfortunately living in a generally invalidating world… My clients have often found themselves in really distressing situations and having to use the skills from that module… to be able to still junction in their jobs or at school without completely unraveling or struggling to get out of bed in the morning.” (Provider #6, Female, 7 years of experience)

Distract (with Wise Mind ACCEPTS), Self-soothing, Improving the Moment, TIP.

TGD youth reported that engaging in activities that provide immediate relief from acute emotional pain and distress by countering adverse physiological responses and providing distraction or self-comfort could be useful.

“TIP [not only provides an] emotional kind of reset, but it also physically helps you reset… splashing your face with cold water kind of shocks you into, “Okay, I need to calm down.”… Going for a run, having some sort of physical exertion, using your physical sense in order to calm yourself down… I think is very helpful, especially when I start spiraling, [like] getting extra anxious about my presentation or whatever.” (TGD Youth #14, Transgender Male, 18 years old)

“If I’m just like looking around and I’m like, this is all wrong… this isn’t me… I don’t match how I see myself on the outside and how I feel on the inside… Just to kind of like, distract yourself… and… focus on something else so that way you can just… breathe for a moment and… focus for a second… It’s not gonna fix it completely but, just to [be able to]… function on a day-to-day basis without it… really impairing you is… a huge necessity.” (TGD Youth #20, Transgender Male, 22 years old)

Radical Acceptance.

Some TGD youth described how radically accepting the reality of a situation that cannot be changed can be particularly appropriate in the context of accepting the reality of being transgender and letting go of the distress related to gender dysphoria.

“When you’re talking about dysphoria… that’s not just something that goes away… With gender dysphoria, you have to talk about radical acceptance more than anything else. There are things you can do. You can cope with it. But it’s one of those things where you have to… accept it in a radical kind of way.” (TGD Youth #8, Transgender Male, 21 years old)

Focusing on Present Moment.

TGD youth noted that being able to focus on the present moment through the use of breathing and other mindfulness exercises, allowed them to center themselves and better cope with various emotional crises. These include anxiety related to their ability to successfully “pass” (i.e., being perceived as cisgender as opposed to their assigned birth sex), anticipatory concerns about being able to medically transition, and in-the-moment crises related to invalidating situations (e.g., experiencing discrimination, having unsupportive family members).

“[I] worry about how I might look in the future because of hormones or passing ability… It is something I’ve struggled with because I didn’t know if I could pass or look how I think I should look. If I could focus on the now instead of what it could be, that would be very helpful.” (TGD Youth #3, Transgender Female, 25 years old)

Subtheme 3: Coping with Interpersonal challenges

TGD youth reported that they often experience invalidation across a myriad of interpersonal relationships and many of these interactions are difficult or impossible to avoid. It is thus critical to have effective interpersonal skills that allow them to assert their gender identity while maintaining self-respect and positive relationships in the context of these challenging social interactions.

“A few weeks ago, one of my managers [who] is really bad with pronouns – she gets the name but the pronouns are off – I was nervous to talk to her about it because I have tried to before. She says, ‘Oh I have known you for a long time, I knew you before you came out, so it is hard for me to switch.’ So, I went to another manager and she talked to her and [then] we talked face-to-face. I said I really need you to use the right pronoun… We will not get the respect we need without advocating for [ourselves].” (TGD Youth #1, Transgender Male, 18 years old)

DEAR MAN, GIVE, and FAST.

Youth endorsed the relevance of the DEAR MAN, GIVE and FAST skills, which focus on advocating for one’s needs and cultivating self-respect while still maintaining positive relationships with others.

“I came out to my family in October and there was a period of about nine months where [my family] just pretended [my TGD identity] didn’t exist and I hadn’t told them anything. I was kind of hoping they would help me talk about it, try to change their behavior. But they never did and I was kind of forced to… be blunt and ask for what I wanted. [To deal with] this experience, I used a lot of [DEAR MAN] skills to try and advocate for myself.” (TGD Youth #30, Transgender Female, 20 years old)

Theme 2: Implementation Challenges

The TGD youth and providers highlighted three areas where some flexibility in the implementation of DBT or contextualizing of DBT skills may be necessary because of the unique challenges faced by TGD youth related to gender dysphoria and discrimination. These areas included skills focusing on body awareness or physiological sensations, self-care focused skills, and interpersonal effectiveness skills.

Subtheme 1: Challenges related to body/somatic focused skills and gender dysphoria

Skills Focusing on Body Awareness and Physiological Sensations.

While many TGD youth and providers found mindfulness and distress tolerance skills to be useful, some reported that body awareness exercises (e.g., body scan, progressive muscle relaxation) and other skills that focus on physiological responses can elicit negative responses and exacerbate gender dysphoria.

“A lot of trans people have… very specific feelings about their body or… physical senses and… being aware of that… being really thoughtful about… how you approach [body awareness exercises is important], [be]cause trans people can have… really negative feelings about their bodies.” (TGD Youth #19, Gender Non-Binary, 20 years old age) “I’ve had a lot of trouble selling progressive muscle relaxation… [because I’ve had client’s say] ‘No I don’t want to be tensing and relaxing my body, I do everything in my power not to feel my body.” (Provider #2, Female, 2 years of clinical experience)

[For] many clients who are who are cisgender… one of the self-soothing techniques we talk about is taking a shower. But that’s actually really anxiety-provoking for some of my trans clients. Taking a shower in general, because of their dysphoria, is just so dysregulating to them. So it’s being mindful about what coping skills or what DBT skills are going to work for that particular population, depending on what their presentation is.” (Provider #6, Female, 7 years of experience)

TGD youth and providers both suggested adapting body awareness exercises to exclude focus on certain body parts, such as chest, legs, and feet, and instead focus on more neutral body parts or external objects.

“A lot of mindfulness exercises might be like, ‘Ok now focus on like, your chest and your breathing.’ To me, that’s a big thing like, chest, I don’t like mine right now so then I’m thinking about it. So I think… just shifting it a little bit and… saying something like… focus on… your legs or your shape or… a different object outside of you [might be helpful].” (TGD Youth #27, Transgender Male, 22 years old)

“Scal[ing] back some of the breathing exercises or scal[ing] back some of that stuff that’s embodied practice. And… when I say scale back what I mean is, just lower the risk a little bit and… focus on more like neutral or less activating body parts.” (Provider #6, Female, 7 of years of clinical experience)

At the same time, some providers stated that there are benefits to exposing TGD youth to aspects of their body that they are uncomfortable with.

“Most of the [TGD youth] I work with, they can’t [do standard exercises]. So we’re just going to do other things. [But I also encourage] people [to get] comfortable with the uncomfortable.” (Provider #9, Female, 12 years of experience)

Skills Focused on Self-Care.

Some providers reported difficulties with encouraging TGD youth to engage in self-care skills, such as the PLEASE skills, because they require youth to focus on issues relating to their physical health. This can elicit strong feelings of gender dysphoria and produce willfulness. Nonetheless, the providers felt that it was important to encourage these self-care skills to improve their client’s overall well-being.

“I’ve heard certain people say to me, “Well, my physical illness is that I was born into the body I shouldn’t be, and nobody will help me with that… I don’t want to eat regularly and hydrate because that means I’ll have to go to the bathroom, and going into the bathroom confronts me with the body I was born in, not the body I want to be in’… [But I think] the PLEASE skills are essential… [so] I’ll connect it back to their life worth living goals and ‘Well, your life worth living goal is to eventually have a body that you feel complete and accepting of and whole of, and I can’t help you get there if you do not eat and starve yourself.’” (Provider #2, Female, 2 years of experience)

Subtheme 2: Challenges related to gender discrimination

Skills Focused on Interpersonal Effectiveness.

A minor theme arose with regards to interpersonal effectiveness skills. While providers acknowledge that interpersonal effectiveness skills are important for TGD youth to develop, they also noted that the interpersonal experiences of TGD youth may differ substantively from those of a cisgender individual. Specifically, TGD youth often encounter unsafe and prejudiced environments where ensuring their own safety and self-respect need to be prioritized to utilize skills effectively.

“I do think the interpersonal effectiveness module could use some work. I think about the conversations that trans individuals have to have with people that maybe have differing opinions or understanding of gender identity and expression, and I just feel like things like the GIVE skill, you know, being gentle and validating other people, I think that’s all well and good. But if they’re in a conversation with somebody who is really creating an unsafe and discriminatory environment, the GIVE skill only works so far. It’s almost like we need to shift and figure out how to help them have conversations that are still allowing them to hold true to who they are while maintaining their own safety. And not… compromising themselves.” (Provider #6, Female, 7 years of experience)

Theme 3: Suggestions to Improve Acceptability & Inclusivity of Intervention Protocol

TGD youth identified three possible modifications to the standard DBT protocol, provider training, and program messaging that could increase the relevance of DBT for TGD youth, including the need for (1) psychoeducation that differentiates between depression and gender dysphoria; (2) compassionate, flexible, and affirming therapists who will advocate for their clients’ needs; and (3) increasing “buy-in” for DBT among the TGD community.

“I thought my dysphoria was depression… Like I thought everyone wanted to be a girl. ‘That’s normal. This is normal.’ It wasn’t. I’ve had signs of depression since I was five and signs of dysphoria since I was five. I probably wouldn’t have realized I had dysphoria since I was five. But [if I was taught to distinguish between depression and gender dysphoria]… I would at least have been able to know for myself [that I wasn’t just depressed] and it would have been easier mentally. I feel like I would be able to practice with my voice more often instead of being stuck with this baritone… I’d be able to have more experience and preparation.” (TGD Youth #5, Transgender Female, 19 years old)

“[My DBT therapist] kind of ruled with an iron fist when I kind of need[ed] more compassion and empathy to receive the best treatment. She would get kind of defensive if she didn’t understand something. And then in group therapy, it was good to learn all the skills, like I still use them a little to this day, but… it felt very ‘you need to this, otherwise,’ ‘there is no other way, you have to do it this way,‘ ‘you need to use DEAR MAN, otherwise you’re not going to get it or it’s not going to be effective.‘” (TGD Youth #14, Transgender Male, 18 years old)

“Speaking from experience, sometimes my therapist can help hold [my parents] accountable, when they are refusing to use my name and pronouns. Sometimes I’m afraid to advocate for myself. Sometimes even when I do advocate for myself, my parents are not receptive. Having someone to back me up and help navigate that discussion would be useful.” (TGD Youth #30, Transgender Female, 20 years old)

Treatment providers also suggested some possible changes for DBT, such as (1) changing the language in the DBT manual to be more gender neutral (e.g., careful use of pronouns when referring to individuals in the DBT manual); and (2) including extra modules on body image skills and dealing with invalidating environments, with extra focus on gender identity acceptance and coping with gender affirmation treatments (e.g., medical procedures).

Discussion

Despite the significant mental health challenges and unique treatment needs for high-risk TGD youth, little is known regarding the acceptability of evidence-based treatments for this population. Previous work has documented the theoretical considerations of DBT for the LGBTQ+ community in general (Skerven et al., 2019; Sloan et al., 2017); however, empirical evidence on its perceived relevance for TGD individuals remains limited. The current study uniquely contributes to the literature by exploring TGD youth and mental health providers’ perspectives of the perceived relevance of DBT for TGD youth with a history of depression, suicidality, and self-harm; and identifying aspects of the DBT modules that could be modified to improve its effectiveness. Overall, the results highlighted the perceived usefulness and relevance of DBT for TGD youth for acute and chronic stressors, many of which are unique to TGD youth.

Most of the perceived implementation challenges reported by TGD youth and providers centered on the influences of gender dysphoria on skill practices. Specifically, TGD youth and providers were concerned that specific skills with a focus on body awareness and acceptance, physiological sensations, and self-care for one’s physical health may increase distress related to gender dysphoria.

In light of these concerns, some treatment modifications were suggested, including (1) modifying body awareness exercises in the Mindfulness module; (2) revising physiological-related self-soothing or coping techniques in the Distress Tolerance module (e.g., taking a shower, progressive muscle relaxation), for youth experiencing significant gender dysphoria; (3) emphasizing self-care skills in the Emotion Regulation module (e.g., self-care of one’s body); and (4) discussing ways to protect one’s safety in hostile and prejudiced environments in the Interpersonal Effectiveness module. These findings highlight the importance of including gender dysphoria in our conceptualization of distress and its alleviation for TGD youth.

Other suggestions for modifications include the use of more gender-neutral language and the addition of TGD-specific psychoeducation and skills modules focused on gender dysphoria, body image issues, gender identity acceptance, and coping with treatments related to gender affirmation (e.g., medical procedures). Additional research is needed to identify more specific coping skills focused on managing gender dysphoria-related distress.

While not specific to DBT, some participants shared that therapists should be more flexible in their approach and act as active advocates for their clients. Consistent with recommended guidelines for providing mental health care to TGD individuals (American Psychological Association, 2015), TGD youth and providers emphasized the diverse experiences of TGD youth and the need for therapists to respect the unique situation of each person. Recognizing the intersectionality of race, gender, and sexual identities would facilitate an improved understanding of marginalized experiences of this group. The youth and providers also noted concerns about feeling emotional distant when using manualized treatments and worksheets in treatment.

The study’s findings shed light on previously unexplored perspectives of TGD youth and providers on the perceived relevance of DBT and provide DBT treatment providers with some critical issues to consider and potential areas for modification of the DBT modules when working with high-risk TGD youth. It also establishes the relevance and foundation for future studies that use quantitative designs to examine the acceptability and feasibility, and eventually effectiveness, of a culturally-adapted version of DBT for TGD youth.

Nonetheless, some key limitations should be noted. First, there were some variations in data collection methods across the groups (e.g., focus group for youth and individual interviews for the providers, which may have introduced some bias in the types of participants (and their perspectives) in each of the groups (e.g., motivations for participating). However, the general alignment of themes across groups in the study results suggests that the methodological differences likely did not substantially affect the findings. Second, the coded themes presented were not checked with the participants; hence it is unclear if any inadvertent bias or misinterpretation occurred in the data analysis process. Third, the study had a largely homogeneous youth sample, comprised of 75% White youth, almost half of whom identified as transgender male (47.4%). This potentially limits our understanding of the views of TGD youth across gender identities, race, and ethnicities; for example, ethnic minority youth may experience unique stressors because of their “double-marginalized” status that require specific supports that may not be included in the suggested DBT modifications. Likewise, the providers were mostly female (90%) and practiced in urban areas in the United States. Therefore, their shared perspectives may be limited to their specific experiences and client populations. In addition, although efforts were made to ensure that the research team included members from diverse backgrounds, all members identified as cisgender; this may have influenced the team’s ability to identify and interpret nuances in the data. Future studies should include a more diverse sample of youth and providers, and research team members, and systematically evaluate a modified DBT protocol based on the current study’s suggestions to verify their benefits.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Seth Burklund Memorial Scholarship from the National Behavioral Intervention Team Association. Dr. Mahaffey’s contribution was also supported by a grant for the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development K23 HD092888-01A1.

Footnotes

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Disclosure of interest: The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- American Psychological Association. (2015). Guidelines for psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming people. American Psychologist, 70, 832–864. 10.1037/a0039906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger I, & Mooney-Somers J (2016). Smoking cessation programs for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex people: A content-based systematic review. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 19(12), 1408–1417. 10.1093/ntr/ntw216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom JM, Woodward EN, Susmaras T, & Pantalone DW (2012). Use of dialectical behavior therapy in inpatient treatment of borderline personality disorder: A systematic review. Psychiatric Services, 63(9), 881–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, & Clarke V (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Budge SL, Israel T, & Merrill CRS (2017). Improving the lives of sexual and gender minorities: The promise of psychotherapy research. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(4), 376–384. 10.1037/cou0000215 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Budge SL, Sinnard MT, & Hoyt WT (2021). Longitudinal effects of psychotherapy with transgender and nonbinary clients: A randomized controlled pilot trial. Psychotherapy, 55(1), 1–11. 10.1037/pst0000310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly MD, Zervos MJ, Barone CJ, Johnson CC, & Joseph CLM (2016). The Mental Health of Transgender Youth: Advances in understanding. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(5), 489–495. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desrosiers L, Saint-Jean M, & Breton J-J (2015). Treatment planning: A key milestone to prevent treatment dropout in adolescents with borderline personality disorder. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 88(2), 178–196. 10.1111/papt.12033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser G, Wilson MS, Garisch JA, Robinson K, Brocklesby M, Kingi T, O’Connell A, & Russell L (2018). Non-suicidal self-injury, sexuality concerns, and emotion regulation among sexually diverse adolescents: A multiple mediation analysis. Archives of Suicide Research, 22(3), 432–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greytak EA, Kosciw JG, & Diaz EM (2009). Harsh Realities: The Experiences of Transgender Youth in Our Nation’s Schools. GLSEN. [Google Scholar]

- Kliem S, Kröger C, & Kosfelder J (2010). Dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder: A meta-analysis using mixed-effects modeling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(6), 936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, & Wilks CR (2015). The course and evolution of dialectical behavior therapy. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 69(2), 97–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little H, Tickle A, & das Nair R (2018). Process and impact of dialectical behaviour therapy: A systematic review of perceptions of clients with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 91(3), 278–301. 10.1111/papt.12156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu RT, & Mustanski B (2012). Suicidal ideation and self-harm in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 42(3), 221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch TR, Trost WT, Salsman N, & Linehan MM (2007). Dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol, 3, 181–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott E, Hughes E, & Rawlings V (2018). The social determinants of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth suicidality in England: A mixed methods study. Journal of Public Health, 40(3), e244–e251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oransky M, Burke EZ, & Steever J (2019). An interdisciplinary model for meeting the mental health needs of transgender adolescents and young adults: The Mount Sinai Adolescent Health Center approach. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 26(4), 603–616. 10.1016/i.cbpra.2018.03.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE (2018). The scientific pursuit of sexual and gender minority mental health treatments: Toward evidence-based affirmative practice. The American Psychologist, 73(9), 1207–1219. 10.1037/amp0000357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, & Safren SA (2019). Adapting evidence-based practice for sexual and gender minorities: The current state and future promise of scientific and affirmative treatment approaches. In Handbook of evidence-based mental health practice with sexual and gender minorities. (pp. 3–22). Oxford University Press. 10.1093/med-psych/9780190669300.003.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Vetters R, Leclerc M, Zaslow S, Wolfrum S, Shumer D, & Mimiaga MJ (2015). Mental health of transgender youth in care at an adolescent urban community health center: A matched retrospective cohort study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(3), 274–279. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.10.264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skerven K, Whicker DR, & LeMaire KL (2019). Applying dialectical behaviour therapy to structural and internalized stigma with LGBTQ+ clients. The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 12, e9, Article e9. 10.1017/S1754470X18000235 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan CA, Berke DS, & Shipherd JC (2017). Utilizing a dialectical framework to inform conceptualization and treatment of clinical distress in transgender individuals. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 48(5), 301–309. 10.1037/pro0000146 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taliaferro LA, McMorris BJ, Rider GN, & Eisenberg ME (2019). Risk and protective factors for self-harm in a population-based sample of transgender youth. Arch Suicide Res, 23(2), 203–221. 10.1080/13811118.2018.1430639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, & Craig J (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veale JF, Watson RJ, Peter T, & Saewyc EM (2017). Mental health disparities among Canadian transgender youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60(1), 44–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villarreal L, Charak R, Schmitz RM, Hsieh C, & Ford JD (2021). The relationship between sexual orientation outness, heterosexism, emotion dysregulation, and alcohol use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual emerging adults. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 25(1), 94–115. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.