Abstract

Purpose

This study was conducted to examine differences in Spiritual Interests Related to Illness Tool (SpIRIT) scores and the degree of spiritual needs (SNs) between patients with terminal cancer and their primary family caregivers and to compare spiritual needs between them.

Methods

The study participants were inpatients with terminal cancer and their primary family caregivers at 40 national hospice centers. The final analysis included 120 SpIRIT surveys from patients and 115 from family members, and 99 SNs questionnaires from patients and 111 from family members. Data analysis was conducted using descriptive statistics, the t-test, one-way analysis of variance, and Pearson correlation coefficients.

Results

There were no significant between-group differences in SpIRIT scores or SNs. The SpIRIT sub-dimensions that ranked high for both patients and primary family caregivers were “maintaining positive perspective”, “loving others”, and “finding meaning”. The SNs sub-dimensions were ranked identically in both groups, in the order of “love and connection”, “hope and peace”, “meaning and purpose”, respectively. In both groups, the recognition of the importance of spiritual matters and religion were major factors influencing SpIRIT scores and SNs.

Conclusion

The SpIRIT scores and degree of SNs of patients with terminal cancer and their primary family caregivers were found to be very closely related, and the needs for coherence and meaning were greater than religious needs. When providing spiritual care for patients with terminal illness, family members should also be considered, and their prioritization of spiritual needs and the importance of spiritual matters and religion shall be taken into account.

Keywords: Terminal care, Patient, Family, Spirituality, Needs assessment

INTRODUCTION

1. Background

Spiritual well-being is an important component of health care for patients with terminal cancer and their family members, with impacts on outcomes including quality of life, positive coping, care satisfaction, and decision-making in the last days of life [1,2]. Spiritual needs increase when people face life-threatening conditions such as terminal cancer, and the spiritual dimension provides important resources when people face physical, psychological, and social pain and struggles that they cannot avoid [2,3].

Human beings are holistic in that their physical, psychological, and spiritual aspects are organically connected [4] and form an open system that continuously interacts with the environment. Therefore, the spiritual needs of terminal cancer patients are closely tied to those of their family members. To provide more effective spiritual care, the spiritual needs of patients and their family members should be considered simultaneously. Family members provide important resources for patient care by directly influencing recovery, coping with the disease, and facilitating difficult therapeutic processes [5].

In order to understand the spiritual needs of participants in a more realistic manner, the spiritual interests related to illness of both care receivers and care providers should be evaluated [6]. Taylor [7] recommended using the term “interest” when discussing the spiritual needs of patients with terminal cancer and their family members from the perspective of care recipients’, since the term “need” implies a lack and could be interpreted negatively. She also suggested that since the spiritual interests of terminal patients and their family members are interconnected, when assessing the spiritual needs of terminal patients, it is important to assess the requirements of patients and family members simultaneously. Versions of the Spiritual Interests Related to Illness Tool (SpIRIT) for patients and family caregivers have been developed to measure their needs simultaneously [7].

At the same time, the spiritual dimension, unique to human beings, influences the condition of the body and mind [8]. With the progression of the disease, the interests of patients with terminal illness move from pain and suffering to the meaning of suffering, the meaning of life, and the meaning of death [9]. Extant measurement tools for spiritual needs are based on spiritual characteristics of the general population; therefore, they are limited in assessing the specific needs of patients with terminal illness [10]. Moreover, these tools are usually developed in Western countries, and considering that spiritual matters are influenced by family, environment, and culture, a tool that is appropriate in the Korean cultural context is needed to assess participants’ spiritual needs adequately [11].

Previous research has employed diverse measurement tools to assess spiritual needs. However, since the spiritual dimension is a core health resource for providing spiritual well-being to terminal patients near death and their family members, the lack of research simultaneously measuring SpIRIT scores in patients with terminal cancer and their family members and comparing their spiritual needs (SNs) with a tool developed based on the Korean cultural context is a major lacuna. In order to provide patient-centered spiritual care, it is also necessary to understand and compare the priorities of patients’ and families’ needs in terms of the sub-dimensions of SpIRIT and SNs.

2. Purpose

The aim of this study was to compare the SpIRIT scores and the degree of SNs of patients with terminal cancer and their family members in order to understand their needs for spiritual needs and to provide foundational information for patient-centered spiritual care. The specific study aims were as follows:

1) To identify the sociodemographic and disease- and spiritual needs-related characteristics of patients with terminal cancer and their family members;

2) To identify differences in SpIRIT scores and the degree of SNs according to the sociodemographic and disease- and spiritual needs-related characteristics of patients with terminal cancer and their family members;

3) To identify differences in sub-dimensions of SpIRIT scores, their relative ranking, and the degree of SNs between patients with terminal cancer and their family members;

4) To identify the correlations between the sub-dimensions of SpIRIT and SNs among patients with terminal cancer and their family members.

5) To identify the factors that influence SpIRIT scores and SNs among patients with terminal cancer and their family members.

METHODS

1. Study design

This comparative study was conducted to shed light on differences between Spiritual Interests Related to Illness (SpIRIT) scores and the degree of spiritual needs (SNs) in order to understand the spiritual needs of patients with terminal cancer and their family members.

2. Subjects

The study population comprised inpatients with terminal cancer at 40 national hospice centers who gave permission for data collection, as well as their family members. The inclusion criteria were: 1) patients who had been admitted to a national hospice center after being diagnosed with terminal cancer and their family members (primary caregivers), 2) those who provided written consent to participate in the study, and 3) those who could understand and respond to the survey. Sample size calculation using G*Power version 3.1 for the 2-sided t-test with significance level of 0.05, power of 0.95, and effect size of 0.80 [10,11] resulted in a sample size of 42 per group. Thus, the sample size of this study was regarded as adequate.

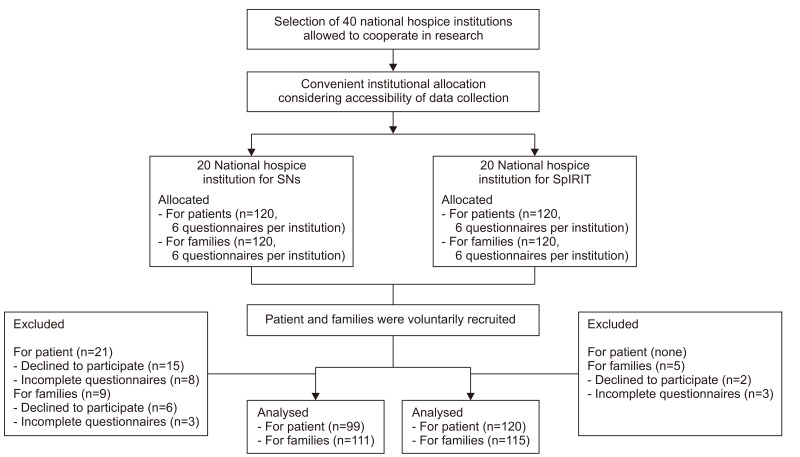

Patients with terminal cancer and their family members may not be physically and psychologically vigorous enough to complete long surveys. Therefore, to reduce the dropout rate and to improve the accuracy of survey responses, the centers were divided into 2 groups (20 centers in each group) by convenience sampling, which took into consideration the convenience of data collection regarding the number of items on the survey and the circumstances at each center. At the first 20 centers, 120 SpIRIT surveys each were distributed to patients and families (6 patients and 6 family members at each center), and at the remaining 20 centers, SNs surveys were distributed in the same manner. At the 20 centers where SpIRIT surveys were distributed, 120 surveys were completed by patients and 118 surveys were completed by family members, of which 120 surveys from patients and 115 surveys from family members were included in the final analysis. At the 20 centers where SNs surveys were distributed, 105 surveys were completed by patients and 114 surveys were completed by family members, of which 99 surveys from patients and 111 surveys of family members were included in the final analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The sampling schema of the present study.

SNs: spiritual needs, SpIRIT: spiritual interests related to illness tool.

3. Study tools

1) Sociodemographic and disease- and spiritual needs-related characteristics

The same sociodemographic and disease- and spiritual needs-related characteristics were measured in participants who completed the SpIRIT survey and those who completed the SNs survey. Information was gathered on the general characteristics of the patients with terminal cancer and their family members, including age, gender, marital status, relationship to the patient (only for family members), education level, religion, and average monthly income. The disease-related characteristics measured were diagnosis, time since diagnosis, and physical, psychological, and economic suffering due to the disease (using a 5-point Likert scale). The spiritual needs-related characteristics measured were importance of spiritual matters and religion (5-point Likert scale) and spiritual support (multiple choice).

2) Spiritual Interests Related to Illness

The Spiritual Interests Related to Illness Tool (SpIRIT) questionnaire was developed by Taylor [7] to measure the spiritual interests of patients with terminal cancer and their family members The translated tool with the permission of the developer was tested content validity. This tool was developed to simultaneously measure the needs of patients and family members, and it measures “interests” rather than “needs” to prevent unintentional negative judgements of the participants. The tool is structured in 8 sub-dimensions (relating to God, loving others, receiving love and spiritual support, finding meaning, maintaining positive perspective, preparing for death, reevaluating beliefs and life, and asking “why?”) and contains 42 items that are answered using a 5-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater spiritual interest related to illness. The Cronbach’s alpha of this tool was 0.95 in Taylor’s original study [7], and the Cronbach’s alpha in this study was 0.95.

3) Spiritual needs

In order to measure the spiritual needs (SNs) of patients with terminal illness, the SNs tool developed by Yong et al. [11] for adult patients with cancer was used with the permission of the developer. The tool is structured in 5 sub-dimensions (relationship with God, meaning and purpose, acceptance of dying, hope and peace, and love and connection) and contains 26 items that are answered using a 5-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater SNs. The Cronbach’s alpha of this tool in the study of Yong et al. [8] was 0.92, and the Cronbach’s alpha of this tool in this study was 0.93.

In order to measure the SNs of family members, the SNs measurement tool developed by Yong et al. [11] was revised and adapted to adequately measure the SNs of family members of cancer patients. The validity and reliability of the revised tool were assessed before administering it [12]. Its content validity was assessed by 4 hospice and palliative care nurses, 1 nursing professor, and 1 hospice doctor, and the content validity index coefficients of each item were greater than or equal to 80%. The tool comprises 26 items scored on a 5-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater SNs. The Cronbach’s alpha of this tool in the study by Kang et al. [12] was 0.94, and the Cronbach’s alpha of this tool in this study was 0.95.

4. Data collection

This study was approved by the ethical review board of S university (IRB-2017040HR) and was conducted from November 5 to December 28, 2017 at 40 national hospice centers, which gave permission for data collection. The researcher visited the National Council of Hospice Centers and explained the purpose of the research. With the support from the president of the council, the consent and cooperation of hospice centers were obtained. The aim and purpose of the study were explained to the hospice team leaders at the participating centers, and the surveys were mailed to the participating centers with a small gift. The hospice team leader or the hospice nurse of each center evaluated the physical condition of their patients and explained the research aims, data collection method, and data confidentiality to eligible participants. Written consent was obtained from patients who volunteered to participate in the research, and the participants completed the surveys. It was explained to the participants that they could withdraw from the study at any point. The completed surveys were mailed back to the researcher.

5. Data analysis

The collected data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

1. Descriptive statistics such as percentiles, means, and standard deviations were calculated for the participants’ sociodemographic and disease- and spiritual needs-related characteristics and other study variables.

2. Differences in study variables according to the sociodemographic and disease- and spiritual needs-related characteristics of study participants were analyzed through the t-test and one-way analysis of variance.

3. Differences in study variables between patients with terminal cancer and their family members were analyzed using the t-test.

4. Correlations between the sub-dimensions of study variables in patients with terminal cancer and in their family members were analyzed using Pearson correlation coefficients.

5. Factors that influenced study variables in patients with terminal cancer and their family members were analyzed using multiple regression.

RESULTS

1. Sociodemographic and disease- and spiritual needs-related characteristics of the study participants

The sociodemographic characteristics demonstrated significant differences between patients and family members were age (P<0.001), gender (P<0.001), marital status (P<0.001), education level (P<0.001), average monthly income (P=0.014) (Table 1). Patients’ average age was around 12 years older than that of their family members, and 53.2% of the patients were male and 46% were female, while 75.6% of the caregivers were female and 24.0% were male. The percentage of married participants was high in both groups (75.2% of patients and 79.3% of family members). In the patients group, 46.8% had graduated from high school, 27.8% had graduated from middle school, and 23.9% had graduated from university. In contrast, 43.4% of family members had graduated from high school, 37.4% had graduated from university, and 13.2% had graduated from middle school. There was no significant difference in religious affiliations between the 2 groups, and there was a high proportion of Protestants in the sample, with 32.4% and 30.8% of patients and family members identifying as Protestants, respectively. In terms of average monthly income, 43.0% of patients reported an average monthly income of less than 2,000,000 won, and 40.0% of patients reported an income between 2,000,000 and 3,000,000 won. Among family members, 41.7% reported an income between 2,000,000 and 3,000,000 won, and 30.0% reported an income of less than 2,000,000 won.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic, Disease, and Spiritual-Related Characteristics of the Study Participants.

| Characteristics | Categories | Patients (N=226) | Primary family caregivers (N=219) | t/x 2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| N (%) or Mean±SD | N (%) or Mean±SD | ||||

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||||

| Age (yr) | 64.06±12.43 | 52.17±15.29 | 8.93 | <0.001 | |

| <50 | 26 (12.1) | 86 (38.6) | 58.88 | <0.001 | |

| 50~59 | 56 (26.2) | 64 (28.7) | |||

| 60~69 | 56 (26.2) | 48 (21.5) | |||

| ≥70 | 76 (35.5) | 25 (11.2) | |||

| Gender | Female | 102 (46.8) | 170 (75.6) | 40.51 | <0.001 |

| Male | 116 (53.2) | 54 (24.0) | |||

| Marital status | Never married | 12 (5.5) | 34 (15.3) | 27.99 | <0.001 |

| Married | 164 (75.2) | 176 (79.3) | |||

| Separated/Divorced | 18 (8.2) | 5 (2.3) | |||

| Widowed/Bereaved | 24 (11.0) | 7 (3.2) | |||

| Relationship with patients | Spouse | - | 91 (40.4) | - | - |

| Child | - | 66 (29.3) | - | - | |

| Parent | - | 33 (14.7) | - | - | |

| Other family | - | 35 (15.6) | - | - | |

| Education level | Middle school | 57 (27.8) | 29 (13.2) | 23.25 | <0.001 |

| High school | 96 (46.8) | 95 (43.4) | |||

| Bachelor’s degree | 49 (23.9) | 82 (37.4) | |||

| Graduate | 3 (1.5) | 13 (5.9) | |||

| Religion | Protestant | 70 (32.4) | 69 (30.8) | 0.30 | 0.990 |

| Catholic | 35 (16.2) | 37 (16.5) | |||

| Buddhist | 40 (18.5) | 44 (19.6) | |||

| Other/None | 71 (32.9) | 74 (33.0) | |||

| Average monthly income (chon won) | <1,999 | 86 (43.0) | 66 (30.3) | 10.66 | 0.014 |

| 2,000~3,999 | 80 (40.0) | 91 (41.7) | |||

| 4,000~5,999 | 24 (12.0) | 39 (17.3) | |||

| >6,000 | 10 (5.0) | 22 (10.1) | |||

| Disease-related characteristics | |||||

| Patient’s diagnosis based on site of the primary cancer | Biliary and pancreatic cancer | 33 (17.4) | 35 (17.6) | - | |

| Small and large intestine cancer | 29 (15.3) | 26 (13.1) | - | ||

| Lung cancer | 25 (13.2) | 39 (19.6) | - | ||

| Urogenital cancer | 21 (11.1) | 26 (13.1) | - | ||

| Liver cancer | 19 (10.0) | 27 (13.6) | - | ||

| Stomach cancer | 19 (10.0) | 17 (8.5) | |||

| Breast cancer | 13 (6.8) | 10 (5.0) | |||

| Blood and lymphatic cancer | 5 (2.6) | 5 (2.5) | |||

| Brain and spinal cancer | 2 (1.1) | 5 (2.5) | - | ||

| Others | 24 (12.5) | 14 (7.0) | - | ||

| Time since diagnosis (mo) | 38.79±48.09 | 28.86±32.72 | 0.013 | ||

| Degree of suffering due to illness (or patient’s illness) (5-point scale*) | Physical suffering | 3.98±1.14 | 3.38±1.08 | <0.001 | |

| Psychological suffering | 3.80±0.92 | 3.77±0.90 | 0.746 | ||

| Economic suffering | 3.24±1.01 | 2.97±0.94 | 0.004 | ||

| Spiritual needs-related characteristics | |||||

| How important are spiritual matters to you now? (5-point scale†) | 3.57±1.10 | 3.50±1.19 | 0.486 | ||

| How important is religion to you now? (5-point scale†) | 3.56±1.03 | 3.47±1.26 | 0.458 | ||

| Spiritual caregiver (multiple choice) | Spouse | 110 (50.7) | 78 (34.8) | ||

| Parents | 16 (7.4) | 71 (31.7) | |||

| Children | 101 (46.5) | 63 (28.1) | |||

| Physicians | 50 (23.0) | 44 (19.6) | |||

| Nurses | 55 (25.3) | 40 (17.9) | |||

| Religious leaders | 99 (45.6) | 68 (30.4) | |||

| Others | 23 (10.6) | 42 (18.8) |

1=not at all; 2=mild; 3=moderate; 4=severe; 5=very severe, †1=not at all; 2=a little bit; 3=some; 4=quite a bit; 5=a great deal.

Biliary and pancreatic cancer was the most prevalent diagnosis of the patients. There was a significant difference in the reported duration since the cancer diagnosis between the patients and the family members (P=0.013). Regarding the levels of physical, psychological, and economic suffering due to the illness, which were measured on a 5-point Likert scale, significant differences were found in physical suffering (P<0.001) and economic suffering (P=0.004) between the patients and the family members.

Regarding the spiritual needs-related characteristics, no significant difference was found in the answer to the question “How important are spiritual matters to you now?” (5-point Likert scale) (P=0.486), and the average score was greater than 3.5 out of 5 in both groups. There also was no significant difference in responses to the question “How important is religion to you now?” (5-point Likert scale) (P=0.458), and the average score was greater than 3.47 in both groups. For the multiple-choice question about spiritual caregivers, the patients reported that their spouses (50.7%), children (46.5%), religious leaders (45.6%), nurses (25.3%), and doctors (23.0%) were their spiritual caregivers, while the family members reported that their spouses (34.8%), parents (31.7%), religious leaders (30.4%), children (28.1%), doctors (19.6%) and nurses (17.9%) were their spiritual caregivers.

2. Differences in SpIRIT items and SNs by sociodemographic, disease-, and spiritual needs-related characteristics of the participants

The SpIRIT items and SNs that demonstrated significant differences according to the participants’ sociodemographic, disease-, and spiritual needs-related characteristics were religion (P<0.001), the importance of spiritual matters (P<0.001), and the importance of religion (P<0.001) (Table 2). The post-hoc analysis results indicated that SNs were significantly higher among Protestants and Catholics than among Buddhists and participants with no religion. For both the SpIRIT items and SNs, participants who recognized spiritual matters or religion as important had higher spiritual interests related to illness and spiritual needs than those who reported a lower level of recognition.

Table 2.

Differences in SpIRIT and SNs by Participants’ Sociodemographic, Disease, and Spiritual Needs-Related Characteristics.

| Characteristics | SpIRIT (5-point scale) | SNs (5-point scale) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Patients (N=120) | Primary family caregivers (N=115) | Patients (N=99) | Primary family caregivers (N=111) | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Mean±SD | t/F(P) (Scheffe) | Mean±SD | t/F(P) (Scheffe) | Mean±SD | t/F(P) (Scheffe) | Mean±SD | t/F(P) (Scheffe) | ||

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||||||||

| Age (yr) | <50 | 3.99±0.39 | 1.37 (0.257) | 3.91±0.49 | 0.34 (0.807) | 3.87±0.53 | 0.65 (0.583) | 3.99±0.50 | 0.36 (0.783) |

| 50~59 | 3.75±0.41 | 3.88±0.44 | 3.71±0.59 | 4.10±0.53 | |||||

| 60~69 | 3.70±0.52 | 3.95±0.61 | 3.89±0.58 | 4.06±0.71 | |||||

| ≥70 | 3.89±0.69 | 4.06±0.52 | 3.94±0.55 | 3.91±0.81 | |||||

| Gender | Female | 3.81±0.57 | 0.13 (0.901) | 3.71±0.52 | -2.71 (0.008) | 3.92±0.57 | 0.91 (0.364) | 3.97±0.44 | -0.46 (0.650) |

| Male | 3.83±0.52 | 4.00±0.47 | 3.82±0.56 | 4.03±0.66 | |||||

| Marital status | Never marrieda | 3.61±0.54 | 0.10 (0.982) | 3.72±0.45 | 4.69 (0.004) | 3.76±0.66 | 2.93 (0.025) | 3.86±0.56 | 0.47 (0.702) |

| Marriedb | 3.82±0.51 | 3.92±0.47 | a,b<c | 3.88±0.51 | 4.05±0.64 | ||||

| Separated/Divorcedc | 3.86±0.65 | 5.00±0.00 | 3.65±0.57 | 4.12±0.43 | |||||

| Widowed/Bereavedd | 3.84±0.68 | 4.11±0.02 | 4.24±0.59 | 4.08±0.47 | |||||

| Relationship with patients | Spouse | - | - | 3.95±0.57 | 0.67 (0.578) | - | - | 4.02±0.66 | 0.03 (0.993) |

| Child | - | - | 3.84±0.44 | - | - | 3.99±0.64 | |||

| Parent | - | - | 3.99±0.39 | - | - | 4.04±0.55 | |||

| Other family | - | - | 4.01±0.48 | - | - | 4.03±0.57 | |||

| Education level | Middle school | 3.89±0.46 | 1.49 (0.221) | 3.66±0.61 | 2.20 (0.092) | 3.84±0.57 | 0.25 (0.863) | 3.85±0.95 | 1.56 (0.205) |

| High school | 3.74±0.56 | 3.90±0.50 | 3.92±0.61 | 4.01±0.51 | |||||

| Bachelor’s degree | 3.88±0.49 | 3.95±0.48 | 3.83±0.45 | 4.02±0.51 | |||||

| Graduate | 4.40±0.20 | 4.27±0.28 | 3.65±0.00 | 4.46±0.41 | |||||

| Religion | Protestant | 4.05±0.53 | 5.86 (<0.001) | 4.18±0.44 | 9.33 (<0.001) | 4.15±0.41 | 10.58 (<0.001) | 4.36±0.39 | 6.44 (<0.001) |

| Catholic | 4.00±0.45 | 4.10±0.44 | 4.31±0.51 | a,b>d | 4.14±0.57 | a>c,d | |||

| Buddhist | 3.60±0.47 | 3.89±0.32 | 3.59±0.53 | a,b>c | 3.87±0.57 | ||||

| Other/ None | 3.58±0.52 | 3.58±0.45 | 3.57±0.53 | 3.72±0.69 | |||||

| Average monthly income (chon won) | <1,999a | 3.81±0.55 | 0.59 (0.623) | 3.91±0.51 | 3.60 (0.016) | 3.87±0.64 | 0.19 (0.902) | 4.06±0.69 | 0.14 (0.939) |

| 2,000~3,999b | 3.84±0.57 | 3.80±0.49 | b<d | 3.84±0.49 | 4.02±0.61 | ||||

| 4,000~5,999c | 3.63±0.36 | 4.01±0.49 | 4.00±0.49 | 3.96±0.56 | |||||

| >6,000d | 3.79±0.41 | 4.25±0.29 | 3.90±0.65 | 4.07±0.35 | |||||

| Disease-related characteristics Physical suffering | Not at all | 3.04±0.00 | 0.49 (0.782) | 4.04±0.55 | 0.96 (0.449) | 3.79±0.48 | 0.83 (0.481) | 4.02±0.21 | 1.39 (0.241) |

| Mild | 3.86±0.55 | 3.83±0.41 | 3.82±0.71 | 4.01±0.66 | |||||

| Moderate | 3.83±0.52 | 3.83±0.46 | 3.81±0.51 | 4.00±0.53 | |||||

| Severe | 3.79±0.59 | 4.03±0.56 | 4.02±0.53 | 3.89±0.74 | |||||

| Very severe | 3.85±0.48 | 4.00±0.46 | 3.87±0.57 | 4.33±0.52 | |||||

| Psychological suffering | Not at all | 3.77±1.03 | 1.12 (0.356) | 4.28±0.53 | 2.17 (0.096) | - | 1.15 (0.334) | 3.98±0.03 | 0.97 (0.427) |

| Mild | 4.09±0.51 | 3.87±0.52 | 4.12±0.60 | 3.59±1.64 | |||||

| Moderate | 3.69±0.50 | 3.93±0.42 | 3.76±0.70 | 4.03±0.49 | |||||

| Severe | 3.84±0.53 | 3.84±0.48 | 3.84±0.48 | 3.97±0.52 | |||||

| Very severe | 3.82±0.54 | 3.92±0.49 | 3.40±0.51 | 4.17±0.69 | |||||

| Economic suffering | Not at all | 3.49±0.54 | 2.04 (0.094) | 3.78±0.44 | 1.51 (0.203) | 3.82±0.86 | 0.74 (0.587) | 3.96±0.23 | 0.23 (0.924) |

| Mild | 3.94±0.40 | 3.89±0.56 | 3.97±0.47 | 4.10±0.62 | |||||

| Moderate | 3.88±0.57 | 3.98±0.47 | 3.79±0.66 | 3.98±0.69 | |||||

| Severe | 3.64±0.53 | 3.97±0.36 | 3.85±0.43 | 4.11±0.59 | |||||

| Very severe | 3.82±0.54 | 3.42±0.76 | 4.09±0.59 | 3.99±0.45 | |||||

| Spiritual needs-related characteristics | |||||||||

| How important are spiritual matters to you now? | Not at alla | 3.02±0.31 | 19.51(<0.001) | 3.31±0.46 | 21.34(<0.001) | 2.98±0.50 | 15.45 (<0.001) | 2.88±1.22 | 19.91 (<0.001) |

| A little bitb | 3.38±0.51 | a,b,c,d<e | 3.58±0.25 | a,b,c,d<e | 3.38±0.43 | a,b,c<e | 3.57±0.46 | a,b,c<e | |

| Somec | 3.63±0.46 | a,b<d | 3.81±0.40 | a,b<d | 3.69±0.52 | a,b<d | 3.87±0.38 | a,b<d | |

| Quite a bitd | 3.92±0.39 | 3.99±0.37 | a<c | 4.01±0.39 | a<c | 4.12±0.40 | a<c | ||

| A great deale | 4.34±0.35 | 4.44±0.33 | 4.30±0.41 | 4.46±0.39 | |||||

| How important is religion to you now? | Not at alla | 3.31±0.76 | 18.66(<0.001) | 3.40±0.55 | 14.61 (<0.001) | 3.06±0.58 | 15.74 (<0.001) | 3.08±1.11 | 19.51 (<0.001) |

| A little bitb | 3.40±0.48 | a,b,c,d<e | 3.65±0.48 | a,b,c<e | 3.35±0.44 | a,b,c<e | 3.80±0.43 | a,b,c<e | |

| Somec | 3.59±0.37 | b<d | 3.76±0.36 | a<d | 3.68±0.51 | a,b<d | 3.81±0.43 | a<b,c,d | |

| Quite a bitd | 3.87±0.44 | 4.00±0.33 | 4.02±0.36 | 4.10±0.36 | |||||

| A great deale | 4.37±0.30 | 4.31±0.40 | 4.31±0.43 | 4.50±0.35 | |||||

SNs: spiritual needs, SpIRIT: spiritual interests related to illness tool.

For the SpIRIT items completed by the family members, significant differences were found by gender (P=0.008), marital status (P=0.004), and monthly family income (P=0.016), and post-hoc analysis demonstrated that spiritual interests were higher among those who were separated or divorced than among those who were single or married, and among those who reported a monthly income greater than 6,000,000 won than among those who reported an income between 2,000,000 to 3,990,000 won.

3. Differences in SpIRIT scores and SNs and the ranking of their sub-dimensions between patients and their family members

No significant differences were found in SpIRIT items between patients and their family members (P=0.136) (Table 3). Among the 8 sub-dimensions, those that demonstrated significant differences between patients and family members were “maintaining positive perspective” (P=0.011) and “reevaluating beliefs and life” (P=0.005). The sub-dimensions with high scores in both patients and family members were “maintaining positive perspective”, “loving others”, and “finding meaning” (in descending order), while “relating to God” showed a low score, as it was ranked seventh by both patients and family members.

Table 3.

Comparison of SpIRIT and SNs Sub-Dimensions between Patients and Their Primary Family Caregivers.

| Spiritual interests related to illness tool (5-point scale) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Sub-dimensions | Patients (N=120) | Primary family caregivers (N=115) | t | P | ||

|

|

|

|||||

| Mean±SD | Rank | Mean±SD | Rank | |||

| 1. Loving others (6 items) | 4.05 (0.54) | 1 | 4.13 (0.49) | 2 | -1.189 | 0.236 |

| 2. Maintaining positive perspective (5 items) | 4.03 (0.61) | 2 | 4.23 (0.60) | 1 | -2.549 | 0.011 |

| 3. Finding meaning (5 items) | 3.93 (0.61) | 3 | 4.04 (0.48) | 3 | -1.538 | 0.125 |

| 4. Preparing for death (4 items) | 3.76 (0.72) | 4 | 3.90 (0.55) | 5 | -1.687 | 0.093 |

| 5. Receiving love and spiritual support (6 items) | 3.75 (0.66) | 5 | 3.82 (0.62) | 6 | -0.771 | 0.441 |

| 6. Reevaluating beliefs and life (4 items) | 3.75 (0.68) | 5 | 3.49 (0.67) | 8 | -2.838 | 0.005 |

| 7. Relating to God (9 items) | 3.71 (0.86) | 7 | 3.75 (0.88) | 7 | -0.366 | 0.714 |

| 8. Asking “why?” (3 items) | 3.51 (0.77) | 8 | 3.92 (0.50) | 4 | 0.225 | 0.822 |

| Total (42 items) | 3.82 (0.54) | 3.92 (0.50) | -1.498 | 0.136 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Spiritual needs (5-point scale) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Sub-dimensions | Patients (N=99) | Primary family caregivers (N=111) | t | P | ||

|

|

|

|||||

| Mean±SD | Rank | Mean±SD | Rank | |||

|

| ||||||

| Love and connection (2 items) | 4.14 (0.70) | 1 | 4.30 (0.74) | 1 | -1.605 | 0.110 |

| Hope and peace (5 items) | 3.98 (0.64) | 2 | 4.17 (0.63) | 2 | -2.161 | 0.032 |

| Meaning and purpose (7 items) | 3.90 (0.64) | 3 | 4.16 (0.66) | 3 | -2.817 | 0.005 |

| Acceptance of dying (7 items) | 3.82 (0.63) | 4 | 3.88 (0.62) | 4 | -0.747 | 0.456 |

| Relationship with God (divine, sacred) (5 items) | 3.68 (0.96) | 5 | 3.74 (1.06) | 5 | -0.442 | 0.659 |

| Total (26 items) | 3.87 (0.57) | 4.01 (0.61) | -1.794 | 0.074 | ||

SNs: spiritual needs, SpIRIT: spiritual interests related to illness tool.

As shown in Table 4, no significant difference was found in the total average score for SNs between patients and family members (P=0.074). The sub-dimensions that were significantly different between patients and family members were “hope and peace” (P=0.032) and “meaning and purpose” (P=0.005). The order of the sub-dimensions from highest to lowest average scores were: “love and connection”, “hope and peace”, “meaning and purpose”, “acceptance of dying”, and “relationship with God (divine, sacred).” The order was identical for both patients and family members.

Table 4.

Correlations among Sub-Dimensions of the SpIRIT and SNs.

| Variables | RG | LO | RLSS | FM | MPP | PD | RBL | AW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| r(P) | r(P) | r(P) | r(P) | r(P) | r(P) | r(P) | r(P) | |

| SpIRIT in patients (n=120) | ||||||||

| RG | 1 | |||||||

| LO | 0.530* | 1 | ||||||

| RLSS | 0.822* | 0.605* | 1 | |||||

| FM | 0.339* | 0.547* | 0.447* | 1 | ||||

| MPP | 0.447* | 0.481* | 0.378* | 0.358* | 1 | |||

| PD | 0.616* | 0.615* | 0.719* | 0.628* | 0.389* | 1 | ||

| RBL | 0.652* | 0.650* | 0.729* | 0.657* | 0.381* | 0.690* | 1 | |

| AW | 0.316* | 0.419* | 0.358* | 0.615* | 0.235* * | 0.447* | 0.585* | 1 |

| SpIRIT in primary family caregivers (n=115) | ||||||||

| RG | 1 | |||||||

| LO | 0.515* | 1 | ||||||

| RLSS | 0.848* | 0.633* | 1 | |||||

| FM | 0.332* | 0.522* | 0.497* | 1 | ||||

| MPP | 0.589* | 0.626* | 0.548* | 0.511* | 1 | |||

| PD | 0.495* | 0.505* | 0.594* | 0.522* | 0.415* | 1 | ||

| RBL | 0.786* | 0.596* | 0.835* | 0.534* | 0.523* | 0.666* | 1 | |

| AW | 0.111 | 0.369* | 0.282* * | 0.430* | 0.169 | 0.419* | 0.369* | 1 |

|

| ||||||||

| Variables | RwG | MP | AD | HP | LC | |||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| r(P) | r(P) | r(P) | r(P) | r(P) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| SNs in patients (n=99) | ||||||||

| RwG | 1 | |||||||

| MP | 0.567* | 1 | ||||||

| AD | 0.488* | 0.627* | 1 | |||||

| HP | 0.383* | 0.668* | 0.640* | 1 | ||||

| LC | 0.426* | 0.499* | 0.499* | 0.507* | 1 | |||

| SNs in primary family caregivers (n=111) | ||||||||

| RwG | 1 | |||||||

| MP | 0.670* | 1 | ||||||

| AD | 0.499* | 0.686* | 1 | |||||

| HP | 0.479* | 0.746* | 0.721* | 1 | ||||

| LC | 0.524* | 0.655* | 0.644* | 0.669* | 1 | |||

AD: acceptance of dying, AW: asking “why?”, FM: finding meaning, HP: hope and peace, LC: love and connection, LO: loving others, MP: meaning and purpose, MPP: maintaining positive perspective, PD: preparing for death, RBL: reevaluating beliefs and life, RG: relating to God, RLSS: receiving love and spiritual support, RwG: relationship with God (divine, sacred), SNs: spiritual needs, SpIRIT: spiritual interests related to illness tool. *P<0.001, P<0.05.

4. Correlations among the sub-dimensions of SpIRIT and SNs in patients and family members

The correlations between the SpIRIT sub-dimensions in the patient group ranged from 0.235 to 0.822, and there was a statistically significant positive correlation (P<0.05) (Table 4). In the family members, the correlations between “relating to God” and “asking ‘why?’” and between “maintaining positive perspective” and “asking ‘why?’”. All other sub-dimensions showed significant positive correlations, with coefficients ranging from 0.332 to 0.848. The correlations between the SNs sub-dimensions ranged from 0.383 to 0.668 in the patients and from 0.479 to 0.746 in the family members, and these positive correlations were statistically significant (P<0.001).

5. Factors influencing SpIRIT scores and SNs of patients with terminal cancer and their family members.

Before conducting the regression analysis, the presence of autocorrelation in the dependent variables was checked using the Durbin-Watson test, and multicollinearity in the independent variables was checked with the variance inflation factor (VIF). The Durbin-Watson statistic (d) was within the range that indicates independence (dU<d<4-dU [1.867<d<2.133]) and was close to 2, suggesting the absence of autocorrelation. The VIF statistic was below 10, indicating that the data were adequate for regression analysis since there was no multicollinearity in the independent variables (Table 5).

Table 5.

Factors Influencing on SpIRIT and SNs.

| SpIRIT | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Predictors | Patients (n=120) | Primary family caregivers (n=115) | ||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||

| B | SE | β | t (P) | VIF | B | SE | β | t (P) | VIF | |

| Constant | 3.684 | 0.134 | - | 27.589 (<0.001) | - | 3.560 | 0.121 | - | 29.537 (<0.001) | - |

| Gender D1 (female) | -0.116 | 0.095 | -0.108 | -1.219 (0.226) | 1.443 | 0.164 | 0.080 | 0.145 | 2.050 (0.043) | 1.175 |

| Marital status D1 (Never married) | -0.100 | 0.308 | -0.025 | -0.325 (0.081) | 1.092 | 0.149 | 0.103 | 0.107 | 1.445 (0.152) | 1.287 |

| Marital status D2 (separated/divorced) | -0.059 | 0.163 | -0.028 | -0.361 (0.719) | 1.149 | 0.727 | 0.255 | 0.197 | 2.845 (0.005) | 1.126 |

| Marital status D3 (widowed/bereaved) | -0.031 | 0.151 | -0.019 | -0.208 (0.836) | 1.522 | 0.112 | 0.268 | 0.030 | 0.418 (0.677) | 1.237 |

| Family monthly income D1 (<1,999) | -0.136 | 0.098 | -0.124 | -1.393 (0.167) | 1.467 | 0.153 | 0.081 | 0.142 | 1.897 (0.061) | 1.310 |

| Family monthly income D2 (4,000~5,999) | -0.320 | 0.134 | -0.199 | -2.387 (0.019) | 1.289 | 0.318 | 0.103 | 0.222 | 3.095 (0.003) | 1.202 |

| Family monthly income D3 (>6,000) | 0.136 | 0.259 | 0.041 | 0.524 (0.602) | 1.149 | 0.329 | 0.116 | 0.223 | 2.824 (0.006) | 1.458 |

| Religion D1 (Buddhist) | 0.006 | 0.121 | 0.005 | 0.050 (0.960) | 1.655 | 0.004 | 0.104 | 0.003 | 0.038 (0.970) | 1.559 |

| Religion D2 (None ) | 0.174 | 0.135 | 0.148 | 1.287 (0.201) | 2.444 | -0.148 | 0.101 | -0.143 | -1.460 (0.148) | 2.249 |

| How important are spiritual matters to you now? | ||||||||||

| D1 (Not at all) | -0.963 | 0.374 | -0.337 | -2.575 (0.012) | 3.155 | -0.747 | 0.222 | -0.474 | -3.369 (0.001) | 4.625 |

| D2 (A little bit) | -0.231 | 0.145 | -0.148 | -1.594 (0.114) | 1.591 | -0.210 | 0.156 | -0.117 | -1.348 (0.181) | 1.764 |

| D3 (Quite a bit) | 0.213 | 0.160 | 0.193 | 1.333 (0.186) | 3.854 | 0.002 | 0.119 | 0.002 | 0.0018 (0.985) | 3.075 |

| D4 (A great deal) | 0.396 | 0.240 | 0.291 | 1.645 (0.103) | 5.761 | 0.419 | 0.183 | 0.335 | 2.289 (0.024) | 5.017 |

| How important is religion to you now? | ||||||||||

| D1 (Not at all) | 0.279 | 0.321 | 0.118 | 0.870 (0.387) | 3.419 | 0.354 | 0.233 | 0.216 | 1.520 (0.132) | 4.733 |

| D2 (A little bit) | -0.232 | 0.163 | -0.144 | -1.419 (0.159) | 1.907 | 0.144 | 0.137 | 0.101 | 1.054 (0.295) | 2.136 |

| D3 (Quite a bit) | 0.145 | 0.161 | 0.131 | 0.896 (0.373) | 3.944 | 0.196 | 0.118 | 0.179 | 1.657 (0.101) | 2.741 |

| D4 (A great deal) | 0.450 | 0.255 | 0.337 | 1.768 (0.080) | 6.694 | 0.131 | 0.164 | 0.115 | 0.798 (0.427) | 4.853 |

| Statistics | R2=.496, Adj R2=.404 | R2=.602, Adj R2=.529 | ||||||||

| F=5.389, P<0.001 | F=8.280, P<0.001 | |||||||||

| Durbin-Watson’ d=1.961 (1.867<d<2.133) | Durbin-Watson’ d=1.821 (1.867<d<2.133) | |||||||||

| Constant | 3.823 | 0.159 | - | 24.022 (<0.001) | - | 3.90.3 | 0.198 | - | 19.704 (<0.001) | - |

| Gender D1 (female) | -0.169 | 0.093 | -0.150 | -1.811 (0.075) | 1.242 | 0.020 | 0.119 | 0.014 | 0.168 (0.867) | 1.220 |

| Marital status D1 (Never married) | 0.059 | 0.179 | 0.027 | 0.332 (0.741) | 1.199 | -0.046 | 0.144 | -0.028 | -0.323 (0.748) | 1.273 |

| Marital status D2 (separated/divorced) | -0.038 | 0.159 | -0.021 | -0.242 (0.810) | 1.357 | 0.135 | 0.322 | 0.038 | 0.418 (0.677) | 1.375 |

| Marital status D3 (widowed/bereaved) | 0.202 | 0.174 | 0.092 | 1.161 (0.250) | 1.134 | -0.091 | 0.257 | -0.029 | -0.355 (0.724) | 1.160 |

| Family monthly income D1 (<1,999) | 0.046 | 0.102 | 0.041 | 0.455 (0.650) | 1.472 | 0.053 | 0.118 | 0.040 | 0.445 (0.657) | 1.393 |

| Family monthly income D2 (4,000~5,999) | 0.228 | 0.150 | 0.130 | 1.523 (0.133) | 1.320 | 0.119 | 0.132 | 0.081 | 0.897 (0.372) | 1.376 |

| Family monthly income D3 (>6,000) | -0.110 | 0.181 | -0.054 | -0.609 (0.545) | 1.413 | 0.054 | 0.197 | 0.024 | 0.274 (0.784) | 1.313 |

| Religion D1 (Buddhist) | -0.377 | 0.136 | -0.241 | -2.767 (0.007) | 1.369 | -0.124 | 0.176 | -0.082 | -0.704 (0.484) | 2.281 |

| Religion D2 (None ) | -0.195 | 0.142 | -0.168 | -1.367 (0.176) | 2.706 | -0.136 | 0.167 | -0.107 | -0.815 (0.418) | 2.897 |

| How important are spiritual matters to you now? | ||||||||||

| D1 (Not at all) | -0.399 | 0.302 | -0.150 | -1.323 (0.190) | 2.321 | -1.282 | 0.461 | -0.501 | -2.783 (0.007) | 5.471 |

| D2 (A little bit) | -0.205 | 0.208 | -0.112 | -0.985 (0.328) | 2.330 | -0.452 | 0.223 | -0.242 | -2.029 (0.046) | 2.397 |

| D3 (Quite a bit) | 0.278 | 0.146 | 0.214 | 1.908 (0.061) | 2.254 | 0.021 | 0.196 | 0.015 | 0.106 (0.916) | 3.205 |

| D4 (A great deal) | 0.306 | 0.187 | 0.241 | 1.635 (0.107) | 3.922 | 0.093 | 0.217 | 0.070 | 0.430 (0.668) | 4.471 |

| How important is religion to you now? | ||||||||||

| D1 (Not at all) | -0.330 | 0.270 | -0.138 | -1.222 (0.226) | 2.290 | 0.281 | 0.412 | 0.126 | 0.682 (0.497) | 5.719 |

| D2 (A little bit) | -0.118 | 0.221 | -0.061 | -0.536 (0.594) | 2.366 | 0.296 | 0.205 | 0.164 | 1.443 (0.153) | 2.172 |

| D3 (Quite a bit) | 0.175 | 0.168 | 0.141 | 1.041 (0.302) | 3.326 | 0.117 | 0.218 | 0.072 | 0.538 (0.592) | 3.059 |

| D4 (A great deal) | 0.308 | 0.214 | 0.236 | 1.439 (0.155) | 4.856 | 0.491 | 0.237 | 0.371 | 2.070 (0.042) | 5.430 |

| Statistics | R2=0.628, Adj R2=0.533 | R2=0.502, Adj R2=0.401 | ||||||||

| F=6.643, P<0.001 | F=4.978, P<0.001 | |||||||||

| Durbin-Watson’ d=2.100 (1.867<d<2.133) | Durbin-Watson’ d=2.132 (1.867<d<2.133) | |||||||||

D: dummy variable (event), SE: standard error, SNs: spiritual needs, SpIRIT: spiritual interests related to illness tool, VIF: variance inflation factor.

The factors that had a negative influence on SpIRIT scores among patients were “spiritual matters are not important” (β=-0.337, P=0.012) and a household income between KRW 4,000,000 and 6,000,000 (β=-0.199, P=0.019), and these two factors explained 40.4% of the variation in SpIRIT scores. Among family members, the factors that had a positive influence on SpIRIT scores were “spiritual matters are very important” (β=0.335, P=0.024), a household income above KRW 6,000,000 (β=0.223, P=0.006), a household income between KRW 4,000,000 and 6,000,000 (β=0.222, P=0.003), being separated or divorced (β=0.197, P=0.005), and female gender (β=0.145, P=0.043). The factor that had a negative influence was “spiritual matters are not important” (β=-0.474, P=0.001), and these factors collectively explained 52.9% of the variation in SpIRIT scores among family members.

Among patients, SNs were negatively associated with Buddhist religion (β=-0.241, P=0.007), and this factor explained 53.3% of the variation. Among family members, negative influences were found between SNs and “spiritual matters are not important” (β=-2.783, P=0.007) and “spiritual matters are a little important” (β=-2.029, P=0.046), and a positive influence was found between SNs and “religion is very important” (β=2.070, P=0.042). These factors explained 40.1% of the variation.

DISCUSSION

To understand the spiritual needs of patients with terminal cancer and their family members, this study aimed to provide useful to data to inform participant needs-centered interventions and spiritual assessments based on measurements made using the SpIRIT questionnaire, which was developed for both patients with cancer and family caregivers, and the SNs tool, which was developed for cancer patients in South Korea.

No significant differences in psychological suffering, the importance of spiritual matters, and religion were found between patients and their family members, and the average score was high in both groups. These results suggest that psychological and spiritual caregiving for patients with terminal illness and their family members is equally important as physical care for patients in the context of hospice and palliative care. In a study of factors that influenced SNs in patients with different cancer stages that was conducted among 285 patients with cancer, anxiety around SNs such as existential needs, internal peace, and loving was reported to be the most significant factor [13]. Moreover, research from North America and Europe similarly reported that the suffering from incurable diseases was accompanied by emotional and spiritual suffering that surpassed physical suffering in importance [14].

Although a high percentage of patients and their family members responded that family members and religious leaders provided them with spiritual support, around 20% reported that nurses and doctors were their spiritual supporters. This result suggests that patients with terminal cancer and their family members seek spiritual support from the hospice and palliative care team (HPCT). Spiritual caregiving from the HPCT is integral for patients who are close to death [6,14], so as the first step, the HPCT should be capable of accurately assessing participants’ unsatisfied spiritual interests.

It was found that Protestants and Catholics had higher SNs than Buddhists and those without religion. Moreover, stronger recognition of the importance of spiritual matters and religion was associated with higher spiritual interests and needs. According to the regression analysis, subjective perceptions of the importance of spiritual matters and religion was a significant factor that explained variation in SpIRIT scores and SNs in both patients and their family members. Since this finding is derived from a survey of inpatients with cancer and their family members at 40 national hospice centers, whether participants are religious, their religious affiliation, and their perceptions of the importance of spiritual matters and religion may be reflected in the core criteria in spiritual assessments.

No significant differences in SpIRIT items or SNs were found between patients and their family members in terms of the total average score. However, higher levels of spiritual interest and spiritual needs were found among family members than among patients. A study from South Korea [5] that also analyzed the spiritual interests of patients with terminal cancer and their family members using the tool developed by Taylor [7] found no significant difference in the item averages of SpIRIT scores. These results imply that the spiritual interests of patients and their family members were closely related. A study by Ross and Austin [14] reported that the suffering and spiritual interests of patients and their family members were connected, and another report [15] suggested that patients facing the end of life and their family members have spiritual and existential needs and that a care guide is needed for the medical team. The findings of both of those studies correspond to the results of this study.

Spirituality is the essence of human nature and is an external expression of the human spirit that seeks transcendental values, purpose and meaning in life, and a life full of peace and hope among relationships based on forgiveness and love [16]. Based on the nature of spirituality, spiritual needs can be characterized as 1) the need for meaning (to pursue the meaning and purpose of existence), 2) the need for connections (to exchange love and forgiveness), and 3) the need for religion and transcendence (to seek hope and transcendental values) [9]. As a result of administering the SpIRIT and SNs tools to patients with terminal cancer and their family members at 20 different national hospice centers each (in total, 40 centers), both patients and their family members ranked coherence, meaning, and religious and transcendental needs as their priorities, and this result has significant implications. When the HPCT is assessing the needs for spiritual care among patients and their family members, they should consider the fulfilment of coherence (such as forgiveness, reconciliation, and giving and receiving love) before religious and transcendental needs. The finding that the need for discovering meaning was stronger than religious and transcendental needs provides evidence that discovering meaning should be an important category in spiritual assessments.

In a study by Hocker et al. [13] that examined SNs among patients with cancer in 4 categories (existential needs, inner peace, actively giving, and religious needs) in both religious and non-religious groups, the SNs for actively giving and inner peace were high, and religious needs ranked third among those who were religious and fourth among those who were not. Moreover, their findings—specifically, that anxiety was the most significant factor that influenced the SNs of existential, inner peace, and actively giving and that coherence was a significant factor in inner peace, religious needs, and actively giving—were similar to the results of this study. In a qualitative study by Hatamipour et al. [17] that explored the SNs of 18 patients with terminal cancer, the results were similar to this study in that content analysis revealed the 4 major themes of connection, peace, meaning and purpose, and transcendence. Based on the above results, it can be inferred that patients with terminal cancer and their family members require a care relationship with the HPCT based on sincerity and spiritual care that inspires inner peace and hope [18]. The results also suggest that the HPCT, especially nurses, play an important role as facilitators of reduced suffering from existential problems through relationships with patients with terminal illness that are founded on sincerity [19,20].

Spiritual caregiving by the HPCT in hospice and palliative care environments should fulfill needs based on human spirituality rather than a religious perspective. This study provides evidence to support needs assessments and interventions for giving and receiving love (coherence) and for existential and relational needs for discovering meaning. A comprehensive discussion of the literature on spiritual assessments [21] reported that practical and gradual spiritual assessments based on participants’ needs with the nature of spirituality, are needed. Patients and their family members express their spiritual interests and needs in various manners, including sensitivity, facial expression or gestures that suggest they would like to talk, conversations in private spaces, and requests for quiet and private spaces [18,22]. Therefore, the capacity to perform sensitive spiritual assessments that sheds light on the SNs of patients and their family members, to empathize, and to provide counseling is integral for HPCT in hospice care.

The correlation coefficients between the sub-dimensions of the SpIRIT and SNs tools in patients with terminal cancer and their family members ranged from 0.3 to 0.7. Correlations between 0.3 and 0.8 suggest internal consistency [23,24]. Therefore, the SpIRIT and SNs tools used in this have excellent internal consistency.

A limitation of this study is that it did not include all national hospice centers; instead, it included patients with terminal cancer and their family members from 40 centers. Nonetheless, this study makes a meaningful contribution to the existing literature on SNs because 1) the same measurement instruments were used to measure the SpIRIT scores and the degree of SNs of both patients and their family members, 2) SpIRIT scores were measured from the perspective of the care receivers, and 3) a measurement tool developed in South Korea was used to measure the SNs of patients and their family members. This study confirmed that the spiritual needs of patients with cancer and their family members were closely related, that the needs for coherence and meaning were higher than religious needs, and that the average score for SpIRIT and SNs were higher among family members than patients. The results of this study provide important evidence for planning spiritual caregiving, both for patients and their family members.

Supplemental Materials

Supplementary materials can be found via https://doi.org/10.14475/kjhpc.2020.23.2.55.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Borneman T, Brown-Saltzman K. Meaning in illness. In: Ferrell BR, Coyle N, Paice JA, editors. Oxford textbook of palliative nursing. 4th ed. Oxford University Press; New York:Oxford University Press;2015: 2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.PaiceMcClement SE. Spiritual issues in palliative medicine. In: Cherny NI, Fallon MT, Kaasa S, Portenoy RK, Currow DC, editors. Oxford textbook of palliative medicine. 5th ed. Oxford University Press; New York:Oxford University Press;2015: 2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CurrowFrankl VE. Man's search for meaning Man's search for meaning. Beacon Press; Boston: c2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delgado-Guay MO. Spiritual care. In: Bruera E, Higginson I, von Gunten, Morita T, editors. Textbook of palliative medicine and supportive care. 2nd ed. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 2016. pp. 1055–62. [Google Scholar]

- 5.MoritaCho JH. Yonsei Univ.; Seoul: 2008. Spiritual needs of family caregivers of patients with cancer [master's thesis] Korean. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hermann CP. The degree to which spiritual needs of patients near the end of life are met. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34:70–8. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.70-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor EJ. Prevalence and associated factors of spiritual needs among patients with the cancer and family caregivers. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33:729–35. doi: 10.1188/06.ONF.729-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cobb M, Puchalski CM, Rumbold B. Spirituality in healthcare, Korean translation Spirituality in healthcare, Korean translation. The Catholic University of Korea Press; Seoul: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kang KA, Kim DB Korean Society for Hospice and Palliative Care. Textbook of hospice & palliative care. Koonja; Paju: 2018. Spiritual care; pp. 449–67. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doyle N, Henry R. Holistic needs assessment: rationale and practical implementation. Cancer Nurs Pract. 2014;13:16–21. doi: 10.7748/cnp.13.5.16.e1099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yong J, Kim J, Han SS, Puchalski CM. Development and validation of a scale assessing spiritual needs for Korean patients with cancer. J Palliat Care. 2008;24:240–6. doi: 10.1177/082585970802400403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang KA, Choi YS, Kim YJ. Reliability and validity of an instrument assessing spiritual needs of families of terminal cancer patients. Korean J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;21:144–51. doi: 10.14475/kjhpc.2018.21.4.144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hocker A, Krull A, Koch U, Mehnert A. Exploring spiritual needs and their associated factors in an urban sample of early and advanced cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Care. 2014;23:786–94. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ross L, Austin J. Spiritual needs and spiritual support preferences of people with end-stage heart failure and their carers: implications for nurse managers. J Nurs Manag. 2015;23:87–95. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sinclair S, Chochinov HM. Communicating with patients about existential and spiritual issues: SACR-D work. Prog Palliat Care. 2012;20:72–8. doi: 10.1179/1743291X12Y.0000000015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Darby K, Nash P, Nash S. Understanding and responding to spiritual and religious needs of young people with cancer. Cancer Nurs Pract. 2014;13:32–7. doi: 10.7748/cnp2014.03.13.2.32.e1059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hatamipour K, Rassouli M, Yaghmaie F, Zendedel K, Majd HA. Spiritual needs of cancer patients: a qualitative study. Indian J Palliat Care. 2015;21:61–7. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.150190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan H, Wilson A, Olver L, Barton C. The family meeting addressing spiritual and psychosocial needs in a palliative care setting: usefulness and challenges to implementation. Prog Palliat Care. 2011;19:66–72. doi: 10.1179/1743291X11Y.0000000001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keall R, Clayton JM, Butow P. How do Australian palliative care nurses address existential and spiritual concerns? J Clin Nurs. 2014;23:3197–205. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nixon A, Narayanasamy A. The spiritual needs of neuro-oncology patients from patients' perspective. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19:2259–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Draper P. An integrative review of spiritual assessment: implications for nursing management. J Nurs Manag. 2012;20:970–80. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hodge DR. Administering a two-stage spiritual assessment in healthcare settings: a necessary component of ethical and effective care. J Nurs Manag. 2015;23:27–38. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pett MA, Lackey NR, Sullivan JJ. Making sense of factor analysis Making sense of factor analysis. Sage, cop.; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blaber M, Jone J, Willis D. Spiritual care: which is the best assessment tool for palliative settings? Int J Palliat Nurs. 2015;21:430–8. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2015.21.9.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.