Abstract

We encountered a 78-year-old Japanese man with IgG4-related sialoadenitis complicated with marked eosinophilia. We diagnosed him with IgG4-RD (related disease) with a submandibular gland tumor, serum IgG4 elevation, IgG4-positive plasma cell infiltration, and storiform fibrosis. During follow-up after total incision of the submandibular gland, the peripheral eosinophil count was markedly elevated to 29,480 /μL. The differential diagnosis of severe eosinophilia without IgG4-RD was excluded. The patient exhibited a prompt response to corticosteroid therapy. His peripheral blood eosinophil count was the highest ever reported among similar cases. We also review previous cases of IgG4-RD with severe eosinophilia.

Keywords: IgG4-related disease, eosinophilia, hypereosinophilic syndrome

Introduction

Immunoglobulin G4-related disease (IgG4-RD) is an immune-mediated condition associated with fibroinflammatory lesions that can occur at nearly any anatomic site (1). It often presents as a multiorgan disease and may be confused with malignancy, infection, hematological disorder, or another immune-mediated condition, such as Sjögren's syndrome or vasculitis, associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs). A 2020 case-control study revealed that among patients with IgG4-RD, allergy was present in 71%, and peripheral blood eosinophilia was detected in 40% (2). However, eosinophilia is usually mild to moderate, with a few cases showing severe eosinophilia (peripheral blood eosinophil count 5,000 /μL) (3-5). Peripheral eosinophilia at 3,000 μL is part of the 2019 American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) classification criteria for IgG4-related disease (1).

We herein report the clinical details of a 78-year-old man with IgG4-RD who presented with marked eosinophilia (29,480 /μL). Our literature search identified six previous cases of IgG4-RD complicated with eosinophilia (4-8). Our patient's peripheral blood eosinophil count was the highest among all reported IgG4-RD patients. We describe this case of IgG4-RD with marked eosinophilia and review the literature.

Case Report

The patient was a 78-year-old Japanese man with a history of bronchial asthma, prostate carcinoma treated by gamma-knife therapy, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, mild renal dysfunction, and mitral valve regurgitation. He had taken the same medications (including antihypertensive and antidiabetic medicines) for many years, with no changes. Eleven years before his referral to our hospital, he had noticed swelling of his submandibular gland; a submandibular gland tumor was then excised at Hospital A. He was told that it was a benign tumor.

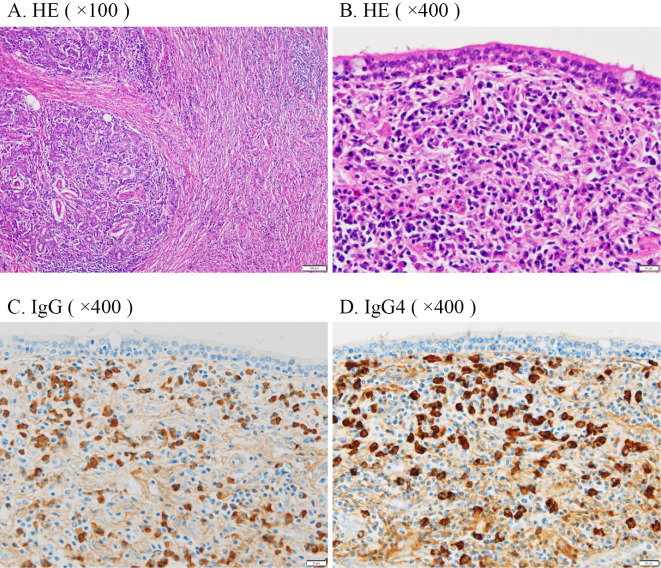

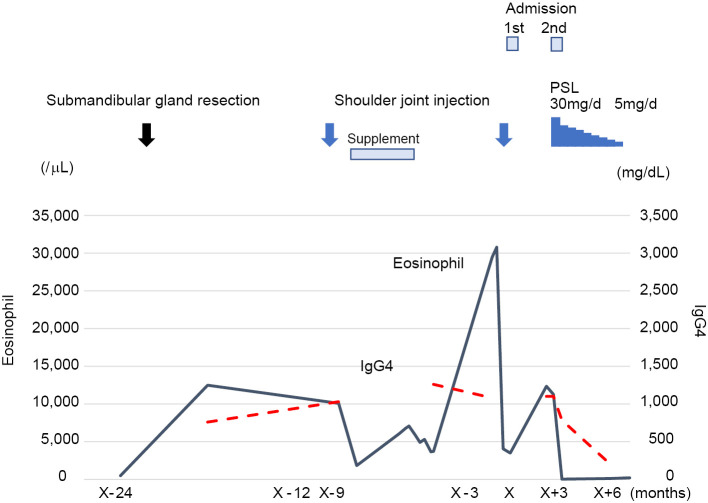

Two years prior to his referral to us, he visited Hospital A again because of swelling of a left submandibular gland. His serum IgG4 concentration was 457 mg/dL. The peripheral eosinophil count was 490 /μL. IgG4-RD was suspected, and he was referred to our hospital. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) revealed a high accumulation in his left submandibular gland (Fig. 1). His left submandibular gland was excised because the tumor could not be completely differentiated from malignancy. The pathological findings showed dense IgG4-positive plasma cell infiltration and storiform fibrosis with 100 IgG4-positive plasma cells/high-power field (HPF) and a 90% IgG4/IgG ratio (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

PET-CT findings. PET/CT showed a high accumulation of FDG in his left submandibular gland.

Figure 2.

Histopathological images of the submandibular gland tumor. The submandibular gland tumor specimen showed (A) infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells and storiform fibrosis [Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining ×100, LPF]; (B) infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells (H&E staining ×400, HPPF); (C) dense infiltration of IgG-positive plasma cells (IgG immune staining ×400, HPF); (D) 100 IgG4-positive plasma cells/HPF and a 90% IgG4/IgG ratio (IgG4 immune staining ×400, HPF). LPF: low-power field, HPF: high-power field

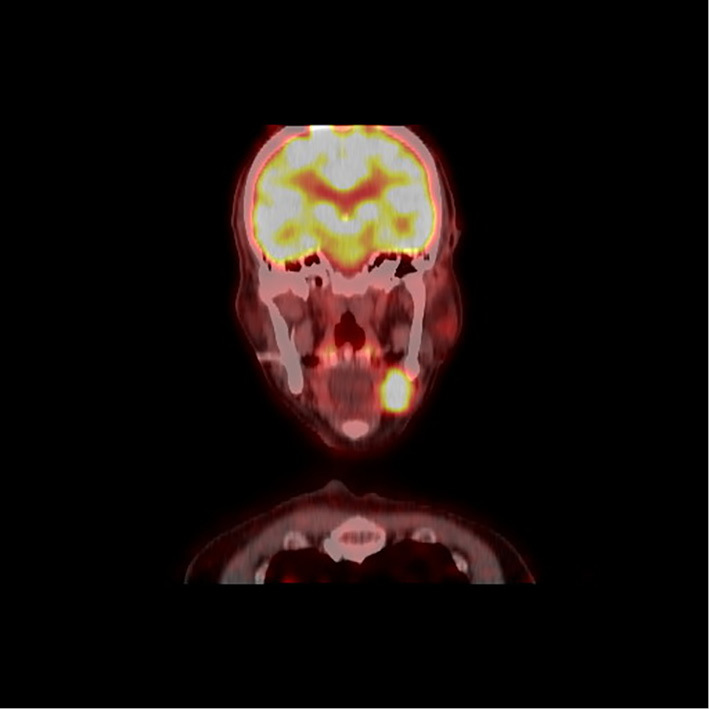

The patient was followed up without any treatment following the gland's excision for approximately one year (Fig. 3). Nine months before his first admission, the patient received an injection of triamcinolone acetonide and lidocaine for a frozen left shoulder at Orthopedic Clinic B. The peripheral eosinophil count decreased from 10,080 /μL to 1,824 /μL. The serum interleukin (IL)-5 concentration was 10 pg/mL (normal range: <4 pg/mL). He also had taken a supplement that included glucosamine, chondroitin, anserine, and quercetin-plus for 5 months; some time after he stopped taking the supplement, his eosinophil count increased to 30,780 /μL.

Figure 3.

Summary of the clinical course of this patient. The serum IgG4 level and peripheral blood eosinophil count were high at resection of the submandibular gland. Although eosinophilia temporarily decreased after the first shoulder joint injection of corticosteroid, the IgG4 level was unchanged. The peripheral blood eosinophil count then increased to 29,400/mL. Although the eosinophil count temporarily decreased after the second shoulder joint injection, it increased again afterward. Finally, oral 30 mg/day PSL resulted in the significant improvement of eosinophilia and IgG4 elevation. PSL: prednisolone, IgG4: immunoglobulin G4, PSL: prednisolone

Three months before his first admission, the patient came to our hospital again for marked eosinophilia and systemic multiple lymph nodes on CT and was admitted to our hospital. At this admission to our hospital, he was 160.0 cm tall and weighed 56.2 kg. His blood pressure was 130/80 mmHg, his pulse was 84 beats/min, his body temperature was 36.7°C. The physical findings revealed no abnormalities other than axillar painless lymphadenopathy. The laboratory data obtained at this admission are shown in Table 1. The white blood cell count in the peripheral blood was 35,100 /μL (eosinophil 29,480 /μL, 84%). The hemoglobin value was 11.2 g/dL, and the platelet count was 326×103/μL. The serum IgG and IgG4 levels were 3,694 mg/dL and 1,080 mg/dL, respectively. The serum IgE level was <25.0 IU/mL. The antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer was ×10,240 and showed a homogenous pattern, but disease-specific antibodies were all negative. The results of tests for human T-cell lymphotropic virus type I (HTLV-I) antibody and anti-parasite antibodies were all negative. The serum level of C-reactive protein (CRP) was 0.28 mg/dL. The values of CH50, C3, and C4 were 39.0 U/mL, 49.6 mg/dL, and 19.7 mg/dL, respectively. Soluble interleukin-2 receptor (IL-2R) was 3,809 U/mL.

Table 1.

Laboratory Data on the First Admission.

| Serology | |||||

| Urinalysis | ESR | 18 | mm/h | ||

| Specific gravity | 1.017 | CRP | 0.28 | mg/dL | |

| pH | 6.5 | IgG | 3,694 | mg/dL | |

| Protein | (1+) | IgG4 | 1,080 | mg/dL | |

| Glucose | (-) | IgA | 59 | mg/dL | |

| Occult blood | (-) | IgM | 25.8 | mg/dL | |

| IgE | <25.0 | IU/mL | |||

| Blood cell count | RF | 5.1 | IU/mL | ||

| WBC | 35.100 | /μL | ANA | 10,240 | ×, Homo |

| Stab | 0 | % | Anti-dsDNA Ab | <10 | IU/mL |

| Seg | 9 | % | Anti-SS-A Ab | <0.5 | U/mL |

| Lymph | 7 | % | Anti-SS-B Ab | <0.5 | U/mL |

| Mono | 0 | % | MPO-ANCA | <1.0 | U/mL |

| Eosino | 84 | % (29.400/μL) | PR3-ANCA | <1.0 | U/mL |

| Baso | 0 | % | CH50 | 39.0 | U/mL |

| RBC | 333×104 | /μL | C3 | 49.6 | mg/dL |

| Hb | 11.2 | g/dL | C4 | 19.7 | mg/dL |

| Ht | 33.1 | % | sIL-2R | 3,809 | U/mL |

| Plt | 32.6×104 | /μL | NSE | 8.2 | ng/mL |

| TARC | 5,607 | pg/mL | |||

| Biochemistry | |||||

| TP | 7.2 | g/dL | Hematology | ||

| Alb | 2.4 | g/dL | BCR-ABL | (-) | |

| T-Bil | 0.3 | mg/dL | NAP score | 308 | |

| AST | 19 | U/L | Anti-HTLV-I Ab | (-) | |

| ALT | 9 | U/L | deletion on 4q12 | (-) | |

| ALP | 77 | U/L | |||

| LDH | 311 | U/L | Bone marrow | ||

| γ-GTP | 12 | U/L | Normocellular marrow | ||

| Amylase | 68 | U/L | with eosinophilia | ||

| Na | 137 | mmol/L | |||

| K | 4.2 | mmol/L | |||

| Cl | 105 | mmol/L | |||

| Ca | 8.6 | mg/dL | |||

| P | 3.1 | mg/dL | |||

| BUN | 26 | mg/dL | |||

| Cre | 1.05 | mg/dL | |||

| eGFR | 52.87 | ||||

| UA | 3.9 | mg/dL | |||

| HbA1c | 5.2 | % | |||

TP: total protein, Alb: albumin, T-Bil: total bilirubin, ALT: alanine aminotransferase, AST: aspartate aminotransferase, LDH: lactate dehydrogenase, γ-GTP: γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, BUN: blood urea nitrogen, Cre: creatinine, eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate, UA: uric acid, HbA1c: hemoglobin A1c, ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate, CRP: C-reactive protein, RF: rheumatoid factor, ANA: antinuclear antibody, Anti-ds-DNA Ab: anti-double stranded DNA antibody, Anti-SS-A Ab: anti-SS-A/Ro antibody, Anti-SS-B Ab: anti-SS-B/La antibody, MPO-ANCA: myeloperoxidase-anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, PR3-ANCA: proteinase3-anti-neutrophil antibody, sIL-2R: soluble interleukin-2 receptor, NSE: neuron specific enolase, TARC: thymus and activation-regulated chemokine, NAP score: neutrophil alkaline phosphatase score

Bone marrow aspiration demonstrated hypereosinophilia without abnormal cells or blastic proliferation. The abnormal T-cell subset was not detected in the peripheral blood on flow cytometry. The chromosomal aberration of the interstitial deletion on 4q12, which results in the fusion of FIP1-like1 (FIP1-L1) and platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha, was not observed.

Chest and abdominal CT demonstrated systemic lymphadenopathy, including supraclavicular, mediastinal, axillar, and para-aortic lymph node swelling, hypertrophy of pericardium, pleural effusion, and renal cysts. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a pituitary adenoma, but no abnormal serum pituitary hormone findings were detected. Gastroduodenal endoscopy and colonoscopy revealed no abnormal findings, including malignancies.

Histologically, the axillar lymph node biopsy specimens revealed 100 IgG4-positive plasma cells/HPF and a 90% IgG4/IgG ratio. A diagnosis of malignant lymphoma was excluded due to the lack of atypical lymphoid cells.

Based on the patient's histopathological findings, laboratory data and clinical course, we diagnosed him with secondary eosinophilia complicated with IgG4-RD. However, the patient did not wish to receive steroid therapy, and he was discharged. He later received another injection of triamcinolone acetonide and lidocaine for his frozen left shoulder at Orthopedic Clinic B. The eosinophil count temporarily decreased to a normal range but then elevated again to 12,350 /μL, and he was admitted to our department again.

He was put on corticosteroid therapy with 30 mg/day prednisolone (PSL), which resulted in an immediate reduction in the severe eosinophil count and IgG4 concentration, and clinical remission has been obtained with PSL. After the first week of 30 mg/day PSL therapy, blood tests were performed twice a week at the hospital until the patient's eosinophil count was reduced to 30 /μL. He was then discharged. Thereafter, the PSL treatment was gradually decreased, consisting of 30 mg/day for the first month, with the dose reduced to 5 mg/day by 2.5 mg/day every 2 weeks for the remainder of the treatment period. The clinical course and concomitant eosinophil count, IgG4 level, and response to prednisone therapy are depicted in Fig. 3.

Discussion

IgG4-RD is a chronic, relapsing, multisystemic immune-mediated fibroinflammatory disease (1). IgG4-RD occurs predominantly in elderly men. Our patient was definitively diagnosed with IgG4-RD based on the 2020 revised comprehensive diagnostic criteria for IgG4-RD (9), i.e. ≥1 organ showing diffuse or localized swelling or a mass or nodule characteristic of IgG4-RD, a serum IgG4 level >135 mg/dL, and pathological findings of >10 IgG4-positive plasma cells/HPF and a ratio of IgG4-/IgG-positive cells >40%. Our patient's axillar lymph node biopsy specimens revealed 100 IgG4-positive plasma cells/HPF and a 70% IgG4/IgG ratio. He was also diagnosed with IgG4-RD because his score based on the 2019 ACR/EULAR classification criteria for IgG4-RD was >20 points (1).

Allergic immunology triggers a T-helper 2-type immune response that induces peripheral blood and tissue eosinophilia (10). To ameliorate the Th2 response, regulatory T (Treg) cells are stimulated to secrete IL-10, which induces class switching to IgG4 along with IL-4 (10). Hypereosinophilia can be induced by various causes, such as allergic disease, parasitic disease, and hemopathy. Although the present patient suffered from bronchial asthma in his past, he had no allergy symptoms. Secondary eosinophilia caused by parasites or drugs was excluded. Although the patient was suspected of having a hematological disorder, such as eosinophilic leukemia, these disorders were excluded based on his laboratory data and pathological findings. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis was also excluded because he did not have ANCA, peripheral neuropathy, or pulmonary or renal involvement despite his history of bronchial asthma.

Hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) is a subcategory of idiopathic eosinophilia, and its diagnosis requires the presence of a peripheral blood eosinophil count of ≥1.5×109/L and eosinophil-mediated organ damage. HES should be distinguished from the term hypereosinophilia, which simply indicates an absolute eosinophil count of ≥1.5×109/L (11). Our patient did not have severe anemia or thrombocytopenia, and he had no organ involvement related to HES. His results were negative for alterations of the myeloid lineage in the bone marrow, FIP1 L1/PDGFRa gene fusion on fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), and abnormal T cells on blood flow cytometry. The lymph node biopsy did not show any infiltration of eosinophils. There was also a good response to glucocorticoids; the diagnoses HES and clonal eosinophilia were thus excluded.

Regarding our patient's history of bronchial asthma, it was reported that of 231 patients with IgG4-RD, 165 (71%) described having lifelong allergy symptoms (2). Peripheral blood eosinophilia was detected in 40% of patients with IgG4-RD. There were also associations between IgG4-RD patients with allergy symptoms who had head and neck involvement [adjusted odds ratio (ORadj) 2.02, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.12-3.62] and those who had peripheral eosinophilia (ORadj 3.27, 95% CI: 1.19-9.02) compared to those without head and neck involvement and without peripheral eosinophilia, respectively (2). Peripheral blood eosinophilia was detected in 38% of 48 patients with IgG4-RD versus 9% of healthy control subjects (p=0.004). Of patients with IgG4-RD, 63% had a history of allergy (12).

Peripheral blood eosinophilia (i.e. >3,000 /μL) is included in the exclusion criteria of the 2019 ACR/EULAR classification criteria for IgG4-RD (1). However, Table 2 summarizes our case and the five previous reports of IgG4-RD patients complicated with marked eosinophilia (4-8). The patients' ages ranged from 9 to 80 years old, and 4 of the 6 were men. Three of the patients were complicated with allergic diseases. Various organs, such as lymph nodes, the liver, gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, kidney, and salivary glands, were affected. The serum IgG4 levels ranged from 239 to 1,780 mg/dL, and the peripheral blood eosinophil counts ranged from 2,000 to 29,480 /μL. To our knowledge, our present patient's peripheral blood eosinophil count was the highest of all six cases.

Table 2.

Summary of Cases Reported in the Literature of IgG4-RD Complicated with Marked Eosinophilia.

| No. | Reference | Age, yrs | Sex | Allergy | Affected organs | Serum IgG4 value, mg/dL | Eosinophil count, /μL | Histology | Treatment | PSL effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | 9 | M | Dust mites | Lymph nodes | 1,420 | 12,600 | Lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, IgG4/IgG ratio 50%, eosinophil infiltration >80% of infiltrating cells | Prednisolone 0.6 mg/kg/d | Good response |

| 2 | 6 | 65 | M | None | Liver | 1,780 | 2,592 | Lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, IgG4/IgG ratio 40%, IgG4-positive cell 40/HPF, eosinophil infiltration>10/HPF | Prednisolone 40 mg/d | Good response |

| 3 | 7 | 30 | F | Allergic rhinitis and atopy | Gastrointestinal tract, peritoneum, pancreas | 183 | 2,020 | Eosinophil infiltration | Prednisolone 40 mg/d | Good response |

| 4 | 8 | 52 | F | None | Liver, lymph nodes | 239 | 3,872 | Lymphoid follicular hyperplasia and IgG4-positive plasma cell infiltration 50/HPF, IgG4/IgG ratio 37%, eosinophil infiltration | Prednisolone 40 mg/d | Good response |

| 5 | 4 | 80 | M | None | Kidney, lymph node, submandibular gland, lung, pancreas, coronary artery | 1,160 | 2,000 | A lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, moderate tissue eosinophilia and interstitial fibrosis and atrophy, IgG4-positive plasma cell >40/HPF, IgG4/IgG ratio>40% | Rituximab 1 g iv x2 | Good response |

| 6 | Our case | 78 | M | Bronchial asthma | Submandibular gland | 457 | 29,480 | A dense IgG4-positive plasma cell 100/HPF, IgG4/IgG ratio 70%, storiform fibrosis | Prednisolone 30 mg/d | Good response |

Not only peripheral blood but also tissue eosinophilia was observed in four patients with IgG4-RD (4-8). Three of the six patients (nos. 1, 3, and 4) were diagnosed with HES. HES can be divided into three subtypes: primary (myeloproliferative), secondary, and unknown. IgG4-RD is known to be a secondary cause of HES (13). In contrast to primary HES, eosinophilia secondary to IgG4-RD is usually mild to moderate, typically quite evanescent, and ablated by steroids or rituximab therapy (4).

Five of these patients responded well to 30-40 mg/day PSL. One patient was successfully treated with rituximab. Our patient's hypereosinophilia normalized temporarily after the injection of triamcinolone acetonide and lidocaine into his left shoulder. We were thus persuaded that his hypereosinophilia responded well to glucocorticoids and began treatment with 30 mg/day PSL.

A recent large-cohort study of IgG4-RD patients suggest that processes inherent to IgG4-RD itself rather than atopy may contribute to eosinophilia and IgE elevation (14). The authors of that study suggested that Th2 cells in IgG4-RD contributed to the eosinophilia.

It was also elucidated that various immune cells, such as B cells, Th2 cells, Treg cells, follicular helper T (Tfh) cells, peripheral helper T (Tph) cells, follicular regulatory T (Tfr) cells, and cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), were involved in IgG4-RD (15), and some studies have reported that the Th2 immune reaction is predominant in IgG4-RD patients (16,17). The Th2 immune response contributes to hypereosinophilia and an elevated IgE level, while Tregs induce the secretion of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) and IL-10, which increases the serum IgG4 concentration (18). Subsequently, serum IgG4 interferes with allergic reactions by competing with IgE in the immune response and binding to mast cells. (16,19-25) Hypereosinophilia and an elevated IgG4 concentration are thus simultaneously observed in some cases.

In allergic diseases such as atopic dermatitis and bronchial asthma, high serum concentrations of thymus and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC) are observed. TARC, also known as C-C motif chemokine ligand 17 (CCL17), has affinity as a ligand for the C-C chemokine receptors CCR4 and CCR8, which are predominantly expressed by Th2 cells, and TARC induces Th2-dominant inflammatory reactions. Our patient's serum TARC concentration was very high at 5,607 pg/mL (normal range <450 pg/mL). Umeda et al. demonstrated that the serum concentrations of TARC in IgG4-RD patients were significantly higher than those of primary Sjögren's syndrome patients and healthy controls (26). The serum TARC concentration in their IgG4-RD group was positively correlated with the IgG4-RD responder index (IgG4-RD RI) score and with the number of organs involved.

In conclusion, we encountered a patient with IgG4-RD who had marked eosinophilia and reviewed six similar previous cases. Hypereosinophilia complicates IgG4-RD, regardless of allergic diseases. HES secondary to IgG4-RD has been reported in several cases. A definitive diagnosis of HES could not be made in the present case. The hypereosinophilia that is associated with IgG4-RD is difficult to differentiate from HES. It is also important to exclude other diseases, such as HES or lymphoma. Clinicians should refrain from simply considering hypereosinophilia complicating IgG4-RD to be due to IgG4-RD and make a careful diagnosis of hypereosinophilia in such cases.

notes

Both written and verbal informed consent were obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1. Wallace ZS, Naden RP, Chari S, Choi H, Della-Torre E, Dicaire J-F, et al. The 2019 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism classification criteria for IgG4-related disease. Ann Rheum Dis 79: 77-87, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sanders S, Fu X, Zhang Y, et al. Lifetime allergy symptoms in IgG4-related disease: a case-control study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 74: 1188-1195, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carruthers MN, Park S, Slack GW, et al. IgG4-related disease and lymphocyte-variant hypereosinophilic syndrome: a comparative case series. Eur J Haematol 98: 378-387, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen LYC, Mattman A, Seidman MA, Carruthers MN. IgG4-related disease: what a hematologist needs to know. Haematologica 104: 444-455, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen C, Chen K, Huang X, Wang K, Qian S. Concurrent eosinophilia and IgG4-related disease in a child: a case report and review of the literature. Exp Ther Med 15: 2739-2748, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chang A, Charoenlap C, Akarapatima K, Rattanasupar A, Prachayakul V. Immunoglobulin G4-associated autoimmune hepatitis with peripheral blood eosinophilia: a case report. BMC Gastroenterol 20: 420-424, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pinto LS, Lamas NJ, Campar A, Ferreira A, Cruz AR. Immunoglobulin G4 related-disease: a rare presentation with secondary hypereosinophilic syndrome and eosinophilic ascites. J Med Cases 12: 107-111, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nagamura N, Ueno S, Fujishiro H, Oonuma H. Hepatitis associated with hypereosinophilia suspected to be caused by HES that also presented with the pathological features of IgG4-related disease. Intern Med 53: 145-149, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Umehara H, Okazaki K, Kawa S, et al. ; the Research Program for Intractable Disease by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (MHLW) Japan. The 2020 revised comprehensive diagnostic (RCD) criteria for IgG4-RD. Mod Rheumatol 31: 529-533, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Weindorf SC, Frederiksen JK. IgG4-related disease: a reminder for practicing pathologists. Arch Pathol Lab Med 141: 1476-1483, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tefferi A, Gotlib J, Pardanani A. Hypereosinophilic syndrome and clonal eosinophilia: point-of-care diagnostic algorithm and treatment update. Mayo Clinic Proc 85: 158-164, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Culver EL, Sadler R, Bateman AC, et al. Increases in IgE, eosinophils, and mast cells can be used in diagnosis and to predict relapse of IgG4-related disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 15: 1444-1452, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Klion AD. How I treat hypereosinophilic syndromes. Blood 126: 1069-1077, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Della Torre E, Mattoo H, Mahajan VS, Carruthers M, Pillai S, Stone JH. Prevalence of atopy, eosinophilia, and IgE elevation in IgG4-related disease. Allergy 69: 269-272, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kamekura R, Takahashi H, Ichimiya S. New insights into IgG4-related disease: emerging new CD4+ T-cell subsets. Curr Opin Rheumatol 31: 9-15, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tabata T, Kamisawa T, Takuma K, et al. Serial change of elevated serum IgG4 levels in IgG4-related systemic disease. Intern Med 50: 69-75, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Umehara H, Okazaki K, Masaki Y, et al. A novel clinical entity, IgG4-related disease (IgG4-RD): general concept and details. Mod Rheumatol 22: 1-14, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tsuboi M, Matsuo N, Iizuka M, et al. Analysis of IgG4 class switch-related molecules in IgG4-related disease. Arthritis Res Ther 14: R171, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yamamoto M, Takahashi H, Suzuki C, et al. Analysis of serum IgG subclasses in Churg-Strauss syndrome the meaning of elevated serum level of IgG4. Intern Med 49: 1365-1370, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Robinson DS, Larché M, Durham SR. Tregs and allergic disease. J Clin Invest 114: 1389-1397, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yamamoto M, Tabeya T, Naishiro Y, et al. Value of serum IgG4 in the diagnosis of IgG4-related disease and in differentiation from rheumatic diseases and other disease. Mod Rheumatol 22: 419-425, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Aalberse RC, Schuurman J. IgG4 breaking the rules. Immunology 105: 9-19, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Aalberse RC, Stapel SO, Schuurman J, Rispens T. Immunoglobulin G4: an odd antibody. Clin Exp Allergy 39: 469-477, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sato Y, Natohara K, Kojima M, Takata K, Masaki Y, Yoshino T. IgG4-related disease: historical overview and pathology of hematological disorders. Pathol Int 60: 247-258, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kawa S, Ito T, Watanabe T, et al. The utility of serum IgG4 concentrations as a biomarker. Int J Rheumatol 2012: 198314, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Umeda M, Origuchi T, Kawashiri SY, et al. Thymus and activation-regulated chemokine as a biomarker for IgG4-related disease. Sci Rep 10: 6010, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]