Abstract

AIM

To determine the incidence and predictive factors for epiretinal membrane (ERM) formation in eyes with complicated primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD) tamponaded with silicone oil (SO).

METHODS

This retrospective case-control study included 141 consecutive patients with (51 eyes) and without (90 eyes) ERM formation after primary pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) and SO tamponade for complicated RRD. The risk factors for ERM were assessed using logistic regression analysis.

RESULTS

The prevalence of postoperative ERM was 36.2% (51/141). Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that the risk factors for ERM in SO-tamponaded eyes included preoperative proliferative vitreoretinopathy [PVR; odds ratio (OR), 2.578; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.580–4.205, P<0.001], preoperative choroidal detachment (OR, 4.454; 95%CI 1.369–14.498, P=0.013), and photocoagulation energy (OR, 2.700; 95%CI 1.047–6.962, P=0.040). The duration of the preoperative symptoms, intraocular SO tamponade time, giant retinal tear, preoperative vitreous hemorrhage, preoperative best-corrected visual acuity, number of breaks, quadrants of RRD, axial length, and photocoagulation points were not predictive factors for ERM formation.

CONCLUSION

Preoperative PVR, choroidal detachment, and photocoagulation energy are risk factors of ERM formation after complicated RRD repair. Better ophthalmic care as well as patient education are necessary for such patients with risk factors.

Keywords: epiretinal membrane, rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, silicone oil, proliferative vitreoretinopathy

INTRODUCTION

Epiretinal membrane (ERM), also known as macular pucker, is a fibrous non-vascular cellular membrane proliferating over the macula region, which can cause decreased visual acuity and metamorphopsia[1]–[2]. In general, ERM includes two types: idiopathic ERMs without a clearly identified cause and secondary ERMs. Among multiple aetiologies associated with secondary ERM, retinal detachment (RD) is a relative common cause. Although recent advances in pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) have led to improved functional and anatomical outcomes of RD, late postoperative complications, such as ERMs, may still develop[3]. ERM formation following rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD) surgery refers to an anomalous scarring process that occurs as a result of inflammation and cellular proliferation. The incidence of ERM formation after RRD surgery is reported to be ranging from 4.6% to 70%[4]–[5], showing higher incidence among cases diagnosed as complex RD. Complicated RD can be considered inclusive of proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR), traction RD, giant retinal tear (GRT), and RD combined with choroidal detachment etc. Due to the inflammation and cellular proliferation, the risk of postoperative PVR was much higher in complicated RD, resulting in poor reattachment rate. Since 1962's, silicone oil (SO) has been widely used for the treatment of complicated RD, greatly improving the anatomical reattachment rate of the retina[6]. Even tamponaded with SO, experimental study showed that postoperative cell proliferation cannot be completely prevented[7]. Furthermore, there have been concerns about the negative effect of SO, including retinal toxicity, stimulation of the mitogenic factors release, as well as concentrating active factors into a smaller volume near the retina[8]. All these factors may accelerate the postoperative ERM development, causing vision loss due to anatomic disturbance of macular. However, until now, there have been few studies evaluating the factors that predict postoperative ERM formation due to complicated RRD tampnaded by SO.

In this study, to understand the pathogenic mechanisms of ERM formation postoperatively, the incidence rate and predictive factors was evaluated in patients with complicated RRD tampnaded by SO.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Ethical Approval

This retrospective study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee and Institutional Review Board of Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center in Sun Yat-sen University (No. 2022KYPJ144). Informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

In the present study, we retrospectively reviewed the electronic medical records of 141 consecutive patients with RRD (141 eyes) treated in Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center between September 2016 and January 2022 by two experienced vitreoretinal surgeons. The definition of “complicated” was determined by reviewing the literature. Complicated RRDs included recurrent detachments, those secondary to trauma, GRTs, rolled edges of retinal breaks, posterior staphyloma, choroidal detachment, and PVR[9]–[10]. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) patients who underwent 25-gauge, three-port PPV combined with SO tamponade for complicated RRD; 2) stable retinal reattachment before SO removal; 3) accurate preoperative description of RRD in clinical charts. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) history of severe ocular trauma; 2) history of severe eye infections or any other disease that could cause changes in the macula; 3) incomplete patient information.

All patients underwent a thorough eye examination, including slit-lamp microscope, non-contact tonometer, fundus photography (fundus camera TRC-50; Topcon, Toyko, Japan), axial length measurement (IOLmaster; Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany), and spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (Spectralis, Heidelberg Engineering GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany). SO (5000 cm; Carl Zeiss, Germany) was used for all cases of complicated RRD. The diagnosis of ERM was confirmed by fundus examination in each patient and based on a highly reflective layer over the inner retinal surface on the spectral-domain optical coherence tomography scan. The included patients were divided into the ERM (ERM formation after primary RRD surgery) and control (no ERM formation after surgery) groups.

The patient data included age of the first occurrence of RRD (in years), sex, preoperative best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), preoperative vitreous hemorrhage (VH), preoperative choroidal detachment, GRT, intraocular SO tamponade time, duration of symptoms, axial length (mm), preoperative PVR grade, number of breaks, quadrants of RRD, laser photocoagulation energy (mW), number of photocoagulation points, and quadrants of RRD. The risk factors were determined using multiple logistic regression. The BCVA was evaluated in logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR). The PVR grading was based on the International Retinal Association Classification of 1983[11].

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed by using SPSS statistical package (version 26.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and P-values less than 0.05 denoted statistical significance. The continuous data was summarized as mean±standard deviation (SD). The categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages (%). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to determine whether continuous numerical variables had normal distributions. The categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test (n<5). The continuous data of the patients with and without ERM were compared using Student's t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test. Logistic regression analysis was used to determine the risk factors for ERM formation. Only significant variables (P<0.05) in the univariate analysis were entered into the multivariate logistic regression model. The multivariate logistic regression model was used to identify the risk factors of ERM formation, and the crude odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each significant factor were obtained.

RESULTS

In total, 141 consecutive patients (141 eyes) underwent PPV with SO tamponade for complicated RRD (Figure 1). Among those patients, 51 (36.2%) developed postoperative ERM. Of 141 eyes with RRD, 86 (61%) were right eyes and 55 (39%) were left eyes. The mean age of the first occurrence of RRD was 49.6±15.1y, and 68.8% (n=97) of the patients were male. Table 1 shows the characteristics of 141 eyes with SO tamponade for RRD.

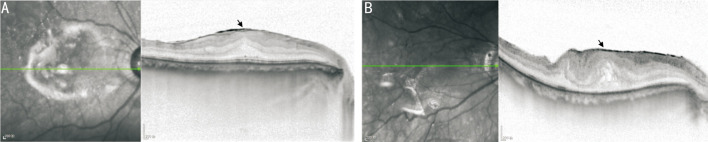

Figure 1. Representative cases with ERM.

A: A 55-year-old male patient developed ERM after RRD surgery. A well-delineated hyperreflective layer (black arrowhead) is identifiable over the retinal surface. B: A 73-year-old male patient with cellophane macular reflex. A hyperreflective layer (black arrowhead) band is on the surface of the retina and globally adherent to the retina, with foveal depression loss and increased central foveal thickness. ERM: Epiretinal membrane; RRD: Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment.

Table 1. Characteristics of SO-tamponaded eyes.

| Characteristic | ERM group (n=51) | Control group (n=90) | P |

| Age (y) | 49.7±17.1 | 49.5±14.0 | 0.322 |

| ≤40 | 10 (19.6) | 15 (16.7) | |

| 41-50 | 10 (19.6) | 28 (31.1) | |

| 51-60 | 17 (33.3) | 31 (34.4) | |

| 61-70 | 11 (21.6) | 14 (15.6) | |

| >70 | 3 (5.9) | 2 (2.2) | |

| Sex | 0.469 | ||

| Male | 37 (72.5) | 60 (66.7) | |

| Female | 14 (27.5) | 30 (33.3) | |

| Duration of the preop. symptoms (mo) | 2.1±2.6 | 2.3±9.0 | 0.005 |

| ≤0.5 | 13 (25.5) | 47 (52.2) | |

| 0.51-1 | 16 (31.4) | 19 (21.1) | |

| 1.1-2 | 8 (15.7) | 8 (8.9) | |

| 2.1-3 | 6 (11.8) | 6 (6.7) | |

| >3 | 8 (15.7) | 10 (11.1) | |

| Duration of SO tamponade (mo) | 8.3±5.3 | 6.8±2.4 | 0.184 |

| ≤3.1 | 1 (2) | 0 | |

| 3.1-6 | 9 (17.6) | 17 (18.9) | |

| 6.1-9 | 25 (49) | 59 (65.6) | |

| >9 | 16 (31.4) | 14 (15.6) | |

| Giant reinal tear | 0.187 | ||

| Yes | 4 (7.8) | 14 (15.6) | |

| No | 47 (92.2) | 76 (84.4) | |

| Preoperative VH | 0.97 | ||

| Yes | 5 (9.8) | 9 (10.0) | |

| No | 46 (90.2) | 81 (90.0) | |

| Preoperative CD | 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 15 (29.4) | 7 (7.8) | |

| No | 36 (70.6) | 83 (92.2) | |

| BCVA (logMAR) | 2.0±0.6 | 1.7±0.6 | 0.034 |

| ≤1 | 4 (7.8) | 2 (2.2) | |

| 1.01-1.50 | 23 (45.1) | 28 (31.1) | |

| 1.51-2.00 | 9 (17.6) | 20 (22.2) | |

| 2.01-2.50 | 10 (19.6) | 32 (35.6) | |

| >2.50 | 5 (9.8) | 8 (8.9) | |

| Number of breaks | 2.3±2.0 | 2.2±1.6 | 0.864 |

| 1 | 26 (51.0) | 44 (48.9) | |

| 2-4 | 17 (33.3) | 38 (42.2) | |

| ≥5 | 8 (15.7) | 8 (8.9) | |

| Quadrants of RRD | <0.001 | ||

| <1 | 0 | 3 (3.3) | |

| 1-<2 | 7 (13.7) | 36 (40.0) | |

| 2-<3 | 13 (25.5) | 24 (26.7) | |

| ≥3 | 31 (60.8) | 27 (30.0) | |

| Axial length (mm) | 26.0±2.5 | 25.3±2.2 | 0.043 |

| PVR grade | <0.001 | ||

| No | 2 (3.9) | 25 (27.8) | |

| A | 0 | 9 (10.0) | |

| B | 4 (7.8) | 30 (33.3) | |

| C1 | 14 (27.5) | 9 (10.0) | |

| C2 | 8 (15.7) | 8 (8.9) | |

| C3 | 8 (15.7) | 7 (7.8) | |

| D1 | 7 (13.7) | 2 (2.2) | |

| D2 | 2 (3.9) | 0 | |

| D3 | 6 (11.8) | 0 | |

| Photocoagulation energy (mW) | 218.6±54.8 | 186.4±38.4 | 0.015 |

| <200 | 35 (68.6) | 77 (85.6) | |

| 201-300 | 13 (25.5) | 12 (13.3) | |

| >300 | 3 (5.9) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Photocoagulation points | 1087.8±438.6 | 990.2±417.8 | 0.464 |

| <400 | 3 (5.9) | 7 (7.8) | |

| 401-800 | 12 (23.5) | 21 (23.3) | |

| 801-1200 | 15 (29.4) | 38 (42.2) | |

| 1201-1600 | 17 (33.3) | 19 (21.1) | |

| >1600 | 4 (7.8) | 5 (5.6) |

ERM: Epiretinal membrane; CD: Choroidal detachment; VH: Vitreous haemorrhage; RRD: Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment; PVR: Proliferative vitreoretinopathy; BCVA: Best-corrected visual acuity; SO: Silicone oil.

n (%)

Univariate analysis revealed that the risk of postoperative ERM was associated with preoperative PVR (P<0.001), preoperative choroidal detachment (P=0.001), duration of preoperative symptoms (P=0.005), initial BCVA (P=0.034), quadrants of RRD (P<0.001), axial length (P=0.043), and photocoagulation energy (P=0.015; Table 1).

Multivariate analysis showed that patients with preoperative choroidal detachment were 4.454 times (95%CI, 1.369–14.498, P=0.013) more likely to have ERM formation than those who without. Eyes with preoperative PVR (OR, 2.578; 95%CI, 1.580–4.205, P<0.001), and higher photocoagulation energy during the surgery (OR, 2.700, 95%CI, 1.047–6.962, P=0.040) also increased the risk of ERM formation after SO tamponade (Table 2).

Table 2. Multivariate analysis of factors associated with ERM formation after SO tamponade for RRD repair.

| Characteristic | OR (95%CI) | P |

| Duration of the preop. symptoms | 1.134 (0.825 to 1.558) | 0.438 |

| Preoperative CD | 4.454 (1.369 to 14.498) | 0.013 |

| BCVA | 1.259 (0.805 to 1.971) | 0.313 |

| Quadrant of RRD | 1.146 (0.647 to 2.029) | 0.641 |

| Axis | 1.401 (0.907 to 2.165) | 0.129 |

| PVR grade | 2.578 (1.580 to 4.205) | <0.001 |

| Photocoagulation energy | 2.700 (1.047 to 6.962) | 0.040 |

CD: Choroidal detachment; ERM: Epiretinal membrane; PVR: Proliferative vitreoretinopathy; RRD: Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment; BCVA: Best-corrected visual acuity; OR: Odds ratio; CI: Confidence intervals; SO: Silicone oil.

DISCUSSION

ERM formation following RRD surgery refers to an anomalous scarring process that occurs as a result of inflammation and cellular proliferation. It requires additional surgery and results in poor visual outcomes. There are inconsistent reports on the risk factors for the formation of ERM, such as GRT, preoperative choroidal detachment, and PVR. To the best of our knowledge, few studies have assessed the predictive factors for ERM formation in patients with complicated RD. In our study, we found a 36.2% incidence of ERM formation after complicated RRD repair using PPV and SO tamponade, which is higher than that reported in a previous study. Our findings indicated that preoperative PVR, preoperative choroidal detachment, and photocoagulation energy were significant and independent risk factors for the formation of postoperative ERM.

According to our analysis, patients with preoperative PVR were more likely to develop ERM after RRD surgery. Similar to our study, Pan et al[7] also reported that the risk of postoperative ERM increased with preoperative PVR[12]. Molecular experiments and animal models have demonstrated that a range of growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines play essential roles in the pathogenesis of PVR[13]–[14]. Following retinal breaks, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), glial, and bone marrow-derived cells are exposed to these factors, resulting in proinflammatory cascade signaling, which facilitates cell proliferation, migration and inflammation. Furthermore, it is unlikely that proliferated cells fail to respond to changes in the inflammatory milieu even after vitrectomy and retinal reattachment. Therefore, cell proliferation and epithelial-mesenchymal transformation of RPE cells take months after RD repair, leading to postoperative ERM formation. Research on PVR has recently focused on proinflammatory factors[15], such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and its signaling pathway, IL-6 deficiency significantly reduces the severity of PVR, which may provide insights into targeted PVR therapy and the prevention of ERM formation[16].

Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment associated with choroidal detachment (RRDCD) is considered a significant preoperative risk factor for retinal reattachment failure, which may be due to the high incidence of postoperative PVR[17]–[18]. This study showed that the incidence of ERM was significantly increased in patients with choroidal detachment, which may result from blood-retinal barrier destruction and excessive inflammatory response. Accumulating evidence from recent experimental and clinical studies on the identification of inflammatory mediators in the vitreous show that RRDCD is associated with higher expressions of plasma proteins, proinflammation cytokines, chemokines, immunoglobulin chains, and complement proteins than RRD[19]–[20]. These factors may aggravate inflammation, facilitate the proliferation and differentiation of RPE, mediate lymphocyte migration, and facilitate the accumulation of the extracellular matrix[21]. Moreover, several immunohistochemical studies have confirmed that serum components, complements, and immunoglobulins were found in ERM[22]–[23]. We presume that the presence of these factors in the vitreous induces a stronger wound-healing response, which may lead to the formation of macular ERM. These findings suggest that anti-inflammatory treatment is extremely important for patients with choroidal detachment during the perioperative period.

Reports of the association between the ERM and preoperative vitreous hemorrhage have been inconsistent. In a retrospective study, postoperative ERM was observed more frequently in patients with preoperative vitreous hemorrhage[24]. Theoretically, a large number of serum components, such as blood cells, cytokines, and various growth factors entering the vitreous cavity, may contribute to the formation of ERM[25]–[26]. Nevertheless, Duquesne et al[26] reported no significant association between vitreous hemorrhage and postoperative proliferation, regardless of the severity of vitreous hemorrhage. Similarly, no significant association was observed between them in this study. We hypothesize that most patients with vitreous hemorrhage have early clinical symptoms due to the perception of shadows and floaters. Therefore, surgical intervention can be performed promptly to remove the vitreous, as well as blood components and cytokines, to prevent postoperative ERM progression.

GRTs are full-thickness retinal breaks extending circumferentially around the retina by 90° or more[27]. In previous studies, GRT was identified as a predisposing factor for ERM formation after RRD repair[28]. Researchers have speculated that greater exposure of the RPE may cause greater release of pigments and cells into the vitreous cavity, consequently leading to a higher risk of proliferation[29]. However, GRT was not significantly correlated with postoperative ERM in our study. This may be explained by the following. First, our study focused on complex RRD characterized by an average of more than two retinal breaks and marked exposure of the RPE, which caused the release of several thousand RPE cells into the vitreous cavity. Second, this discrepancy may be due to bias related to the selection of different cases and the limitations of some retrospective studies.

Retinal laser photocoagulation is commonly used to treat RRD to allow the formation of strong adhesions between the retinal neuroepithelium and RPE around breaks[30]. However, photocoagulation can sometimes induce several complications such as ERM[7]. This is consistent with our study, which showed that photocoagulation energy, rather than the number of photocoagulation points, was a significant risk factor for ERM formation. Previous studies revealed that energy-induced damage enhances macrophage-mediated inflammation, proliferation of RPE cells, and significant Müller cell reactions that contribute to PVR[7],[31]. In addition, numerous studies have shown that cell migration and proliferation after laser photocoagulation are increased by the upregulated expression of various pro-inflammatory cytokines and immunological markers, which are reportedly involved in the proliferative changes of RPE cells[32]. In addition, high laser energy can severely damage the blood-retinal barrier, allow the active RPE cells and macrophages to enter the vitreous cavity through retinal breaks and subsequently deposit on the macular area to turn into fibrovascular tissue and form the ERM[33]. Although laser photocoagulation is an effective and necessary treatment for RRD, excessive photocoagulation should be avoided.

Most postoperative ERM risk factors involve intravitreal dispersion of RPE cells, inflammation, or breakdown of the blood-ocular barrier, which are prerequisites for ERM formation. The prevention of postoperative ERM is challenging; thus, careful preoperative examination, early surgery, and regular postoperative follow-up are essential. Furthermore, there are several ways to reduce the risk of postoperative ERM formation, including reducing surgical trauma, using pharmaceutical adjuncts, and lowering SO thresholds[34]. Regarding surgical intervention for RRD, methods that induce the excessive breakdown of the blood-ocular barrier, such as excessive laser photocoagulation, should be avoided. Moreover, there is a need to improve surgical instruments and techniques to reduce surgical damage. The internal limiting membrane (ILM) plays a crucial role in cell proliferation via its scaffolding properties. Researchers have reported that concomitant ILM removal during RRD surgery can reduce the incidence of postoperative ERM[35]. Despite of this, the use of ILM peeling in ERM surgery remains controversial because there is no evidence that it improves vision, and it can damage the inner retinal layers and physiology of Müller cells. Vitreoretinal surgeons should consider the risk factors for postoperative ERM when deciding to perform PPV with or without ILM peeling in patients with RRD because of the risks associated with additional surgery. In addition, drug adjuvant therapies, including anti-inflammatory, anti-proliferative, and anti-growth factor therapies, have been shown to improve surgical outcomes[36]. Studies have shown that the concomitant use of steroids such as intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide and dexamethasone can prevent the progression of ERM, improve visual acuity, and reduce the risk of recurrence of ERM[37]; however, there has been no consensus on the benefits of intravitreal injection for ERM prevention[38]. Thus, further research is required to determine the most effective drug, dosage, and timing of administration.

Our study had several limitations. First, it was a retrospective study based on electronic and paper charts. Second, the follow-up durations were not uniform. For further analyses, extended prospective studies should be conducted to evaluate long-term outcomes.

In summary, the prevalence of ERM was 36.2% for eyes with complicated RRD treated with PPV and SO tamponade. We found that preoperative PVR, choroidal detachment, and photocoagulation energy were the main predictive factors for postoperative ERM formation. For these risk factors, both surgeons and patients should be aware of the increased likelihood of developing ERM. The findings here provide a reference for future research that aimes at the prevention and treatment of postoperative ERM.

Acknowledgments

Foundation: Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81570865).

Conflicts of Interest: Qian YJ, None; Xiang W, None; Sun YM, None; Mijit A, None; Jiang ZH, None; Wei YT, None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Katira RC, Zamani M, Berinstein DM, Garfinkel RA. Incidence and characteristics of macular pucker formation after primary retinal detachment repair by pars plana vitrectomy alone. Retina. 2008;28(5):744–748. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318162b031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirakata T, Hiratsuka Y, Yamamoto S, Kanbayashi K, Kobayashi H, Murakami A. Risk factors for macular pucker after rhegmatogenous retinal detachment surgery. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):18276. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-97738-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weng CY, Gregori NZ, Moysidis SN, Shi W, Smiddy WE, Flynn HW., Jr Visual and anatomical outcomes of macular epiretinal membrane peeling after previous rhegmatogenous retinal detachment repair. Retina. 2015;35(1):125–135. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matoba R, Kanzaki Y, Doi S, Kanzaki S, Kimura S, Hosokawa MM, Shiode Y, Takahashi K, Morizane Y. Assessment of epiretinal membrane formation using en face optical coherence tomography after rhegmatogenous retinal detachment repair. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2021;259(9):2503–2512. doi: 10.1007/s00417-021-05118-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishikawa K, Akiyama M, Mori K, Nakama T, Notomi S, Nakao S, Kohno RI, Takeda A, Sonoda KH. Drainage retinotomy confers risk of epiretinal membrane formation after vitrectomy for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment repair. Am J Ophthalmol. 2022;234:20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2021.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cibis PA, Becker B, Okun E, Canaan S. The use of liquid silicone in retinal detachment surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 1962;68:590–599. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1962.00960030594005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pan Q, Gao Z, Hu X, Wu Q, Zheng JW, Zhang ZD. Risk factors for epiretinal membrane in eyes with primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment that received silicone oil tamponade. Br J Ophthalmol. 2023;107(6):856–861. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2021-320121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Semeraro F, Russo A, Morescalchi F, Gambicorti E, Vezzoli S, Parmeggiani F, Romano MR, Costagliola C. Comparative assessment of intraocular inflammation following standard or heavy silicone oil tamponade: a prospective study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2019;97(1):e97–e102. doi: 10.1111/aos.13830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang JC, Ryan EH, Ryan C, Kakulavarapu S, Mardis PJ, Rodriguez M, Stefater JA, Forbes NJ, Gupta O, Capone A, Jr, Emerson GG, Joseph DP, Eliott D, Yonekawa Y, Primary Retinal Detachment Outcomes (PRO) Study Group Factors associated with the use of 360-degree laser retinopexy during primary vitrectomy with or without scleral buckle for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment and impact on surgical outcomes (pro study report number 4) Retina. 2020;40(11):2070–2076. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000002728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tosi GM, Balestrazzi A, Baiocchi S, Tarantello A, Cevenini G, Marigliani D, Simi F. Complex retinal detachment in phakic patients: previtrectomy phacoemulsification versus combined phacovitrectomy. Retina. 2017;37(4):630–636. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000001221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The classification of retinal detachment with proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Ophthalmology. 1983;90(2):121–125. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(83)34588-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Telander DG, Yu AK, Forward KI, Morales SA, Morse LS, Park SS, Gordon LK. Epithelial membrane protein-2 in human proliferative vitreoretinopathy and epiretinal membranes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57(7):3112–3117. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-17791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harada C, Mitamura Y, Harada T. The role of cytokines and trophic factors in epiretinal membranes: involvement of signal transduction in glial cells. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2006;25(2):149–164. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong CW, Cheung N, Ho C, Barathi V, Storm G, Wong TT. Characterisation of the inflammatory cytokine and growth factor profile in a rabbit model of proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):15419. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-51633-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mysore Y, Del Amo EM, Loukovaara S, Hagström M, Urtti A, Kauppinen A. Statins for the prevention of proliferative vitreoretinopathy: cellular responses in cultured cells and clinical statin concentrations in the vitreous. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):980. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-80127-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen X, Yang W, Deng X, Ye S, Xiao W. Interleukin-6 promotes proliferative vitreoretinopathy by inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition via the JAK1/STAT3 signaling pathway. Mol Vis. 2020;26:517–529. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma T, Gopal L, Badrinath SS. Primary vitrectomy for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment associated with choroidal detachment. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(12):2282–2285. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)91230-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu Y, Yue Y, Tong N, Zheng P, Liu W, An M. Anatomic outcomes and prognostic factors of vitrectomy in patients with primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment associated with choroidal detachment. Curr Eye Res. 2019;44(3):329–333. doi: 10.1080/02713683.2018.1540705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dai Y, Wu Z, Sheng H, Zhang Z, Yu M, Zhang Q. Identification of inflammatory mediators in patients with rhegmatogenous retinal detachment associated with choroidal detachment. Mol Vis. 2015;21:417–427. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo S, Chen Y, Yang L, Gong X, Wu Z. The complement system in retinal detachment with choroidal detachment. Curr Eye Res. 2022;47(5):809–812. doi: 10.1080/02713683.2022.2038634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang H, Zheng S, Mao Y, Chen Z, Zheng C, Li H, Sumners C, Li Q, Yang P, Lei B. Modulating of ocular inflammation with macrophage migration inhibitory factor is associated with Notch signalling in experimental autoimmune uveitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2016;183(2):280–293. doi: 10.1111/cei.12710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baudouin C, Fredj-Reygrobellet D, Gordon WC, Baudouin F, Peyman G, Lapalus P, Gastaud P, Bazan NG. Immunohistologic study of epiretinal membranes in proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1990;110(6):593–598. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)77054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rouberol F, Chiquet C. Proliferative vitreoretinopathy: pathophysiology and clinical diagnosis. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2014;37(7):557–565. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu KY, Chin EK, Bennett SR, Williams DF, Ryan EH, Dev S, Mittra RA, Quiram PA, Davies JB, Parke DW, 3rd, Boldt HC, Almeida DRP. Predictive factors for proliferative vitreoretinopathy formation after uncomplicated primary retinal detachment repair. Retina. 2019;39(8):1488–1495. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000002184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishida Y, Iwama Y, Nakashima H, Ikeda T, Emi K. Risk factors, onset, and progression of epiretinal membrane after 25-gauge pars Plana vitrectomy for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Ophthalmol Retina. 2020;4(3):284–288. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2019.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duquesne N, Bonnet M, Adeleine P. Preoperative vitreous hemorrhage associated with rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: a risk factor for postoperative proliferative vitreoretinopathy? Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1996;234(11):677–682. doi: 10.1007/BF00292353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gutierrez M, Rodriguez JL, Zamora-de La Cruz D, Flores Pimentel MA, Jimenez-Corona A, Novak LC, Cano Hidalgo R, Graue F. Pars Plana vitrectomy combined with scleral buckle versus pars Plana vitrectomy for giant retinal tear. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;12(12):CD012646. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012646.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heo MS, Kim HW, Lee JE, Lee SJ, Yun IH. The clinical features of macular pucker formation after pars Plana vitrectomy for primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment repair. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2012;26(5):355–361. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2012.26.5.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taleb EA, Nagpal MP, Mehrotra NS, Bhatt K, Goswami S, Noman A. Giant retinal tear retinal detachment etiologies, surgical outcome, and incidence of recurrent retinal detachment after silicone oil removal. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2020;13(3):117–122. doi: 10.4103/ojo.OJO_206_2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liao L, Zhu XH. Advances in the treatment of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Int J Ophthalmol. 2019;12(4):660–667. doi: 10.18240/ijo.2019.04.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou C, Qiu Q. 360° versus localized demarcation laser photocoagulation for macular-sparing retinal detachment in silicone oil-filled eyes with undetected breaks: a retrospective, comparative, interventional study. Lasers Surg Med. 2015;47(10):792–797. doi: 10.1002/lsm.22430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tababat-Khani P, Berglund LM, Agardh CD, Gomez MF, Agardh E. Photocoagulation of human retinal pigment epithelial cells in vitro: evaluation of necrosis, apoptosis, cell migration, cell proliferation and expression of tissue repairing and cytoprotective genes. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e70465. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tababat-Khani P, de la Torre C, Canals F, Bennet H, Simo R, Hernandez C, Fex M, Agardh CD, Hansson O, Agardh E. Photocoagulation of human retinal pigment epithelium in vitro: unravelling the effects on ARPE-19 by transcriptomics and proteomics. Acta Ophthalmol. 2015;93(4):348–354. doi: 10.1111/aos.12649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fallico M, Russo A, Longo A, Pulvirenti A, Avitabile T, Bonfiglio V, Castellino N, Cennamo G, Reibaldi M. Internal limiting membrane peeling versus no peeling during primary vitrectomy for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13(7):e0201010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mahmood SA, Rizvi SF, Khan BAM, Khan TH. Role of concomitant internal limiting membrane (ILM) peeling during rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD) surgery in preventing postoperative epiretinal membrane (ERM) formation. Pak J Med Sci. 2021;37(3):651–656. doi: 10.12669/pjms.37.3.3576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ralph A, Lemire CA, Seto B, Arroyo JG. Intravitreal methotrexate for recalcitrant epiretinal membrane reproliferation. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2022;53(1):49–51. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20211209-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fallico M, Maugeri A, Romano GL, Bucolo C, Longo A, Bonfiglio V, Russo A, Avitabile T, Barchitta M, Agodi A, Pignatelli F, Marolo P, Ventre L, Parisi G, Reibaldi M. Epiretinal membrane vitrectomy with and without intraoperative intravitreal dexamethasone implant: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:635101. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.635101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sane SS, Ali MH, Kuppermann BD, Narayanan R. Comparative study of pars plana vitrectomy with or without intravitreal dexamethasone implant for idiopathic epiretinal membrane. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68(6):1103–1107. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1045_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]