Abstract

This systematic review and meta-analysis investigated the impact of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) treatment in management of eyes with non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR) without centre involving diabetic macular oedema (CI-DMO). We searched multiple databases for all randomised clinical trials (RCTs) that evaluated anti-VEGF treatment versus observation in eyes with NPDR without CI-DMO. Data was collected for six outcomes (best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) improvement, diabetic retinopathy severity score (DRSS), central subfield thickness, progression to vision threatening complications (VTCs), ocular adverse events and quality of life measures). Risk of bias was assessed using Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomised trials (RoB 2) and certainty of evidence was assessed using Grade of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE). We identified a total of 2 unique RCTs that compared aflibercept and sham to treat a total of 811 eyes. For BCVA change, there was a small, clinically insignificant benefit for aflibercept treatment at year 2 (MD 0.70, 95% CI 0.02–1.38, GRADE rating: MODERATE). DRSS demonstrated a statistically significant improvement with aflibercept use at year 2 (RR 3.76, 95% CI 2.75–5.13, GRADE rating: MODERATE). VTCs were significantly less in aflibercept arm at year 2 (RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.23–0.40, GRADE rating: MODERATE). In conclusion, aflibercept treatment versus observation in eyes with NPDR without CI-DMO can result in reduced risk of development of VTCs and regression of DRSS score over 2 years. Future trials are needed to increase the precision of the treatment effect and to provide data on quality-of-life metrics.

PROSPERO Registration: CRD42021288608.

Subject terms: Retinal diseases, Oedema

Introduction

Landmark clinical trials in ophthalmology have established the significant benefit for treatment of diabetic macular oedema (DMO) and proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) [1–7]. These studies have informed guidelines and clinical practise globally [8–10]. However, to date, the focus for ocular treatment has been reactive in nature, where patients are treated when they develop vision threatening complications (VTC) including centre-involving DMO (CI-DMO), and PDR.

There is robust evidence that non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR) without CI-DMO is a progressive disease that can lead to meaningful morbidity and is a risk factor for the development of VTC [11]. Independent of VTC development, multiple studies have reported associations between NPDR and reduced visual function, reduced quality of life and higher risk of falls [11–15].

NPDR progression has also been associated with development of PDR and subsequent vision loss [16]. Despite the significant burden of NPDR without CI-DMO, current standard of care involves monitoring patients with this level of retinopathy and intervening with intraocular treatment or scattered laser photocoagulation is only indicated when patients develop DMO/PDR or in some cases of severe NPDR where patient compliance to follow-up maybe a concern [17, 18]. The primary rationale for monitoring and not intervening with treatment at this earlier stage has been the lack of robust evidence to suggest that early intervention can modify the natural course of disease and improve longer term patient outcomes.

Over the past decade, a growing body of evidence has demonstrated a positive effect of intraocular anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) treatment on disease modification of diabetic retinopathy (DR). Post-hoc analyses of intervention trials have demonstrated anti-VEGF treatment can improve DR severity score (DRSS) levels [19–24]. There is also some evidence that anti-VEGF treatment reduces progression of retinal non-perfusion [25]. These surrogate biomarkers of disease pathology provide a pathophysiologic rationale for considering treatment earlier in the course of the disease, especially among eyes with NPDR without CI-DMO.

Despite the clinical need and the biological plausibility rationale, evidence syntheses evaluating potential benefits and risks for anti-VEGF treatments in with NPDR without CI-DMO are lacking. The recent publication of two large randomised clinical trials (RCTs) further supports a timely meta-analysis [26, 27]. As such, we performed a meta-analysis to assess clinical trial data and estimate the treatment effect for anti-VEGF treatment in patients with NPDR without CI-DMO.

Methods

Eligibility criteria for considering studies for this review

This meta-analysis is reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (http://www.prisma-statement.org; accessed Oct 19th, 2021) (Fig. S1). We prospectively registered the study protocol PROSPERO (CRD42021288608). This study was exempt from ethics approval as all synthesis were performed using already published data.

All references underwent a two-stage screening process first assessing titles and abstracts, followed by full papers. Inclusion criteria were as follows: The criteria for inclusion included: (1) randomised controlled trials (RCTs), (2) studies with eyes with NPDR without CI-DMO, (3) studies using any anti-VEGF modalities compared with placebo. Two reviewers evaluated the studies separately for inclusion and exclusion criteria and discrepancies were resolved by a third arbitrator.

The following outcome measures were identified as clinically important for NPDR treatment:

Change in best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) reported at 52 weeks and 100–104 weeks.

Change in diabetic retinopathy severity score (DRSS) levels at 52 weeks and 100–104 weeks [28].

Change in central subfield thickness (CST) at 52 weeks and 100–104 weeks.

Frequency of progression to VTCs (defined as development of PDR or CI-DMO) at 100–104 weeks.

Ocular adverse events (endophthalmitis, retinal detachment, intraocular pressure elevation, iris neovascularization, vitreous haemorrhage) at 100–104 weeks.

Quality of life measure.

Continuous variables were collected with means ± standard deviation (SD). Best corrected visual acuity was reported on a continuous scale. Categorical parameters were collected using percentages of the total sample. DRSS improvement and VTCs were reported as proportions.

Search Methods for identifying studies

On August 8, 2021, the authors conducted a systematic search to capture references on Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, and Cochrane Central published from inception. The sensitive search strategy was devised in collaboration with an academic research librarian and involved MeSH headings and text terms mapping to diabetic retinopathy and equivalents and anti-VEGF therapy and equivalents as illustrated in Table S1. The initial electronic search was supplemented by hand searching the reference lists from included studies to identify any missing studies. Captured citations were exported to Covidence (Veritas health innovation, Melbourne, Australia) for further screening.

Study selection

Two reviewers (JSX, DP) working independently and in duplicate, reviewed the titles and abstracts of search records and subsequently the full texts of records for potentially eligible articles. We resolved discrepancies between reviewers by discussion or referral with a third party (GSS).

Data collection, risk of bias assessment and grading of recommendations, assessment, development and evaluation

Two independent reviewers (JSX, DSP), working independently and in duplicate, collected data using a pilot-tested extraction sheet, designed in Microsoft Excel (Version 16.52). Discrepancies in data collection were resolved through discussion or with a third independent reviewer (GSS).

In the event of missing data, the corresponding author or sponsoring pharmaceutical company was contacted to obtain clarification [29]. In the absence of important summary data, we performed analyses based on the data as reported and assumed that the data were missing completely at random.

Two reviewers (VC, GSS) working independently and in duplicate, assessed risk of bias using version 2 of the Cochrane risk-of-bias for randomised trials (RoB 2) [30]. For each eligible outcome, we assessed the risk of bias across the following domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, masking of outcome assessors, missing outcome data, outcome measurement and selective outcome reporting. Outcomes were classified to be at ‘low’, ‘some concerns’ or ‘high’ risk of bias with the overall rating of risk of bias being the least favourable domain. Missing outcome data was not considered to be a problem if loss to follow-up was balanced between the study arms and the reason for loss to follow-up was reported to be unrelated to the outcome of the study.

We assessed the certainty of the evidence with the Grade of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) [31]. The GRADE approach involves separate grading of quality of evidence for each patient-important outcome followed by determining an overall quality of evidence across outcomes. Two reviewers (VC, GSS) rated each domain for each comparison separately and resolved discrepancies by consultation. We rated the certainty for each comparison and outcome as high, moderate, low or very low, based on considerations of risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, publication bias and imprecision. Decisions around size of effect for the GRADE outcomes were made around clinical decision-making threshold where this has been established. For BCVA, a 5 ETDRS letter change was established as the clinical threshold. For other clinically relevant biomarkers of disease severity (reduction in VTCs, change in CST, DRSS, ocular adverse events), there currently does not exist a threshold for an effect size that would indicate favouring an intraocular treatment versus observation. As such, decisions around size of effect for these outcomes were made by consensus amongst the authors.

Data synthesis and analysis

The unit of analysis used in the study was individual eyes as only one eye from each patient was enroled in the trials.

Where there were missing data due to participant dropout, the analysis was conducted based on participants with complete data.

Studies were assessed for clinical heterogeneity based on study details such as disease severity, baseline BCVA etc. Statistical heterogeneity between trial results was assessed using the chi-square test and the I2 value and reported along with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Chi-square analysis resulting in p value below 0.10 were considered an indicator of statistically significant heterogeneity. The I2 statistic was used to interpret the magnitude of heterogeneity. In accordance with Cochrane guidelines, I2 values were classified as below [32]:

-

i.

0 to 40%: might not be important.

-

ii.

30 to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity.

-

iii.

50 to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity.

-

iv.

75 to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

We performed random-effects meta-analysis for all outcomes. Mean differences were used to report continuous outcomes along with their 95% CI. Categorical outcomes are summarised as relative risks and associated 95% Cis. All analyses were performed using Review Manager (RevMan version 5.3). Identification of publication bias was carried out if more than10 studies could be identified. In that case we planned to assess the asymmetry of the funnel plot.

Results

Selection of studies

Figure S2 presents the PRISMA flow diagram. We identified a total of 9452 records through database searching, of which 6473 unique references remained after removal of duplicates. Of the 6473 records in title and abstract screening, 85 progressed to full text screening. Of these 85 reports, 65 were excluded due to incorrect study design, incorrect population, incorrect treatment or indiscernible results. Further, 8 studies did not have any available data or were still in the recruitment phase [13, 33–39]. The remaining 8 eligible reports corresponded to 2 unique trials [26, 27].

Characteristics of included studies

Table 1 presents trial characteristics. The two unique RCTs were PANORAMA and Protocol W [26, 27].

Table 1.

Summary of eligible studies for NPDR management with aflibercept.

| # | Study, author | Date | Study Location | Study Design | Interventions | Drug | Number of eyes (baseline) | Follow-up (weeks) | Baseline Age | Female (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Panorama Brown et al. [26] | 2021 | International Multicenter | RCT |

2q16 2q8/PRN Sham |

Aflibercept |

2q16 n = 135; 2q8/PRN n = 134; Sham n = 133 |

24, 52, 100 | 55.7 | 177/402 (44.0) |

| 2 | Protocol W Maturi et al. [27] | 2021 | North America | RCT | 2q16 Sham | Aflibercept | 2q16 n = 200; Sham n = 199 | 104 | 56 | 169/399 (42.4) |

NPDR non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy, RCT randomised controlled trial, PRN pro re nata, IVA 2q16 intravitreal aflibercept 2 mg every 16 weeks, IVA 2q8/PRN intravitreal aflibercept 2 mg every 8 weeks with PRN dosing after week 56.

PANORAMA included patients with DRSS level 47 or 53. PANORAMA compared 3 groups using 2 mg aflibercept—2q16 group (aflibercept injection every 16 weeks after 3 monthly doses and 1 every other month dose), aflibercept 2q8/PRN group (aflibercept every 8 weeks after 5 monthly doses with pro re nata (PRN) dosing in year 2) or sham group [26] Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of outcomes for NPDR management with aflibercept.

| # | Study | Intervention | VA change at 52 weeks (mean ± SD) | VA change at 100–104 weeks (mean ± SD) | Patients with >=2-step DRSS score improvement at 52 weeks (%) | Patients with >=2-step DRSS score improvement at 100–104 weeks (%) | CST Improvement at 52 weeks (mean ± SD) | CST Improvement at 100–104 weeks (mean ± SD) | Proportion of Eyes who have 20/20 BCVA or better at 100–104 weeks (%) | Proportion of Eyes with VA loss of 10 or more letters at 100–104 weeks (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Panorama Brown et al. | IVA 2q16 | 1.7 ± 3.5 | 1.5 ± 3.6 | 88/135 (65.2) | 84/135 (62.2) | 18.9 ± 24.9 | 18.6 ± 28.2 | 76/135 (56.3) | 6/135 (4.4) |

| IVA 2q8/PRN | 1.3 ± 3.5 | 0.8 ± 3.8 | 107/134 (79.9) | 67/134 (50.0) | 24.9 ± 22.1 | 15.2 ± 23.6 | 62/134 (46.3) | 12/134 (9.0) | ||

| Sham | 0.5 ± 3 | 0.6 ± 3.2 | 20/133 (15.0) | 17/133 (12.8) | −5.3 ± 38.3 | −10.3 ± 55.5 | 78/133 (58.6) | 8/133 (6.0) | ||

| 2 | Protocol W Maturi et al. | IVA 2q16 | −0.6 ± 6.2 | −0.9 ± 5.8 | 52/172 (30.2) | 69/154 (44.8) | 7 ± 19 | 6 ± 27 | 120/160 (75.0) | 11/160 (6.9) |

| Sham | −1.3 ± 4.9 | −2 ± 6.1 | 18/162 (11.1) | 22/161 (13.7) | −3 ± 27 | 1 ± 28 | 119/166 (71.7) | 14/166 (8.4) |

NPDR non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy, RCT randomised controlled trial, PRN pro re nata, IVA 2q16 intravitreal aflibercept 2 mg every 16 weeks, IVA 2q8/PRN intravitreal aflibercept 2 mg every 8 weeks with PRN dosing after week 56.

DRCR.net Protocol W included patients with DRSS level 43, 47 or 53. Protocol W compared 2 groups using 2 mg aflibercept—2q16 group (aflibercept injection given at baseline; 1, 2, and 4 months; and every 4 months thereafter) or sham group [27] Table 2. In total, the studies comprised a total of 811 eyes, of which 415 were treated with anti-VEGF pharmacotherapy and 396 were treated with sham. Since the goal of this review was to assess the role of anti-VEGF treatment compared to sham treatment, data from different treatment paradigms was pooled. Further, both studies used aflibercept and there were no eligible studies using any other anti-VEGF agents.

Risk of bias and GRADE certainty of evidence

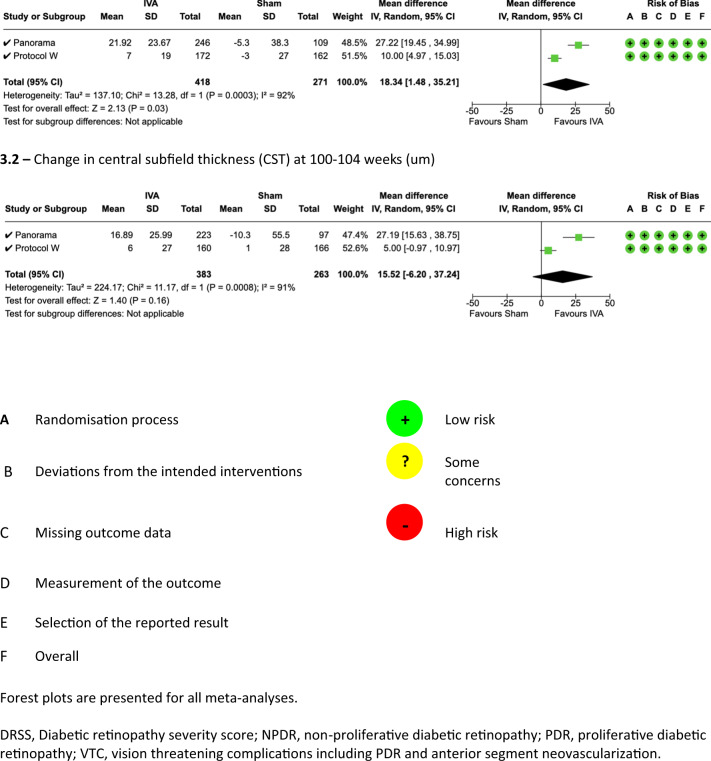

Risk of bias assessment was carried out an outcome level and the results are presented along with the Forrest Plot in Figs. 1 and S3.

Fig. 1.

Forest plots for visual, severity and anatomical outcomes compared between anti-VEGF and sham dosing regimens for NPDR.

Risk of bias was rated low for all outcomes asides from complication rate outcome. Since the investigators were not masked to the intervention and some of the complications were subjective assessments on clinical examination, this resulted is ‘some concern’ for both RCTs on this outcome.

The GRADE evaluation for all outcomes is reported in Table S2. There was MODERATE certainty of evidence for BCVA outcomes, DRSS improvement, VTCs and ocular adverse events at 2 years. There was LOW certainty of evidence CST change at 2 years.

Visual acuity

Visual acuity outcomes at 52 weeks were statistically significantly better in eyes randomised to aflibercept compared to those randomised to sham (MD 0.92 letters, 95% CI 0.31–1.53, P = 0.003, I2 = 0%, GRADE rating: MODERATE, Fig. 1.1.1 and Table S2). However, the 95% CI did not cross the widely accepted clinical decision threshold of 5 ETDRS letters.

Similarly, visual acuity outcomes at weeks 100–104 were statistically significantly better in eyes randomised to aflibercept compared to those randomised to sham (MD 0.70, 95% CI 0.02–1.38, P = 0.04, I2 = 0%, GRADE rating: MODERATE, Fig. 1.1.2 and Table S2). Again, the 95% CI did not cross the widely accepted clinical threshold of 5 ETDRS letters.

Diabetic retinopathy severity score (DRSS)

At week 52, more eyes in the aflibercept arm significantly improved DRSS levels by 2-steps or greater in the aflibercept arm versus the sham arm (RR 3.68, 95% CI 2.09–6.48, p = 0.00001, I2 = 68%, GRADE rating: LOW, Fig. 1.2.1 and Table S2).

At week 100–104, DRSS levels were statistically significantly better in eyes randomised to aflibercept compared to those randomised to sham (RR 3.76, 95% CI 2.75–5.13, P = 0.0001, I2 = 0%, GRADE rating: MODERATE, Fig. 1.2.2 and Table S2).

Central subfield thickness (CST)

CST at 52 week was statistically significantly better in eyes randomised to aflibercept compared to sham (MD 18.34, 95% CI 1.48–35.21, P = 0.03, I2 = 92%, GRADE rating: LOW, Fig. 1.3.1 and Table S2).

At weeks 100–104, there was no significant difference in terms of CST change between the aflibercept arm and the sham arm (MD 15.52, 95% CI −6.20–37.24, P = 0.16, I2 = 91%, GRADE rating: LOW, Fig. 1.3.2 and Table S2).

Progression to vision threatening complications (VTC)

VTC was defined as development of PDR and CI-DMO. At weeks 100–104, proportion of eyes developing VTCs was significantly less in the aflibercept arm compared to the sham arm (RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.23–0.40, P = 0.00001, I2 = 0%, GRADE rating: MODERATE, Fig. S3.1.1 and Table S2).

Ocular adverse events

At weeks 100–104, pooled estimate of important adverse events (endophthalmitis, retinal detachment, IOP elevation, iris neovascularization, vitreous haemorrhage) found no statistically significant difference between the aflibercept arm compared to the sham arm (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.46–0.97, P = 0.04, I2 = 0%, GRADE rating: MODERATE, Fig. S3.2.1 Tables 3 and S2).

Table 3.

Summary of adverse outcomes for NPDR management with aflibercept.

| Panorama | Protocol W | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown et al. | Maturi et al. | |||||

| 2q16 (%) (n = 135) |

2q8/PRN (%) (n = 134) |

Sham (%) (n = 133) |

2q16 (%) (n = 200) |

Sham (%) (n = 199) |

||

| Development of CI-DME | 100–104 weeks | 14 (10.4) | 18 (13.4) | 44 (33.1) | 7 (3.5) | 25 (12.6) |

| Development of PDR | 100–104 weeks | 9 (6.7) | 8 (6.0) | 33 (24.8) | 3 (1.5) | 15 (7.5) |

| Endophthalmitis | 100–104 weeks | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (1.5) | 0 (0) |

| Retinal Detachment | 100–104 weeks | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (1.0) | 2 (1.0) |

| IOP Elevation | 100–104 weeks | 2 (1.5) | 3 (2.2) | 2 (1.5) | 15 (7.5) | 17 (8.5) |

| Iris Neovascularization | 100–104 weeks | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.5) |

| Vitreous Haemorrhage | 100–104 weeks | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.5) | 12 (6.0) | 25 (12.6) |

NPDR non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy, RCT randomised controlled trial, PRN pro re nata, IVA 2q16 intravitreal aflibercept 2 mg every 16 weeks, IVA 2q8/PRN intravitreal aflibercept 2 mg every 8 weeks with PRN dosing after week 56.

Quality of life

None of the studies reported quality of life measurements.

Discussion

This review of high-quality randomised trials found that the only anti-VEGF agent assessed for NPDR without CI-DMO management was aflibercept. Our meta-analysis found that intravitreal aflibercept treatment for management of patients with NPDR without CI-DMO leads to a significant regression of DRSS score and reduces the risk of development of VTCs over 2 years.

There has been limited evidence generation that aims to address the role for anti-VEGF treatment in management of eyes with NPDR without CI-DMO. Despite the clinical need to minimise potential for disease progression and the biological plausibility that early treatment may slow the course of disease, there have been no meta-analyses addressing important patient outcomes as a result of intervention with anti-VEGF treatment at earlier stages in the disease process.

One of the strengths of this review is that the outcomes assessed for this intervention were deemed to be important from a patient care perspective. In terms of patient-important outcomes, visual acuity change was the key outcome that was assessed. This study demonstrates that intravitreal aflibercept treatment compared to sham likely results in little to no difference in terms of BCVA change at year 1 (small unimportant effect, GRADE rating: MODERATE) and year 2 (small unimportant effect, GRADE rating: MODERATE) for patients with NPDR without CI-DMO.

We report multiple clinically relevant biomarkers of disease severity in this review. As discussed in the methods, a limitation of this review is the lack of consensus around when to intervene with respect to intraocular treatment for these biomarkers. We used clinical judgement to classify effects as trivial, small important effect, moderate effect or large effect as per the GRADE guidelines for describing the results. These summary judgements are described below.

DRSS level is an important clinical biomarker of disease severity that was assessed in this review. A 2-step or greater improvement is clinically relevant and previous studies have demonstrated that DRSS level improvement is correlated with functional and anatomic improvement [40]. Although this improvement has been demonstrated in previous studies with anti-VEGF treatment in the context of DMO and/or PDR, this study provides an estimate for this outcome in patients with NPDR without CI-DMO [40]. The evidence suggests that intravitreal aflibercept treatment may result in a large increase in the proportion of eyes with a 2-step or greater DRSS improvement at year 1 (large effect, GRADE rating: LOW). At year 2, intravitreal aflibercept likely results in a large increase in the proportion of eyes with a 2-step or greater DRSS improvement (large effect, GRADE rating: MODERATE). The lower quality of evidence at year 1 stems from “substantial” heterogeneity with an I2 of 68%. This could represent clinical heterogeneity as PANORAMA included two aflibercept algorithms (2q8 and 2q16 after loading dose) compared to Protocol W which had only one active treatment arm (2q16 after loading doses). However, the heterogeneity was classified as “might not be important” due to an I2 of 0% at year 2. This could imply that despite different treatment algorithms, consistent VEGF suppression over the long-term leads to DRSS regression regardless of the precise treatment algorithm. Since the precise biological mechanisms for DRSS level improvement with anti-VEGF treatment remains to be determined, future long-term outcomes will be important to assess the durability of this anatomic improvement.

Another important clinical biomarker for disease severity assessed was the potential to avoid VTCs with anti-VEGF treatment. When patients reach this level of disease burden, they are committed to intensive long-term treatment regimens to stabilise the disease in order to prevent vision loss. This study demonstrated that intravitreal aflibercept treatment compared to observation likely reduces development of VTCs at 2 years (moderate effect, GRADE rating: MODERATE).

Lastly, the pooled estimate demonstrates that intravitreal aflibercept treatment likely does not increase risk of clinically significant ocular adverse events (endophthalmitis, retinal detachment, IOP elevation, iris neovascularization or vitreous haemorrhage) compared to observation (no effect, GRADE rating: MODERATE). However, it is important to note that the RCTs were not powered to assess for all adverse events and estimates for individual adverse events demonstrates are imprecision.

There are important limitations to consider when interpreting the findings of this meta-analysis. Panorama and Protocol W collectively included patients meeting a definition of moderate NPDR to severe NPDR. Hence, the conclusions of this review may not be applicable to patients with less than moderate NPDR. In addition, the goal of this review was to assess the effect of anti-VEGF treatment versus monitoring in terms of clinically important outcomes. However, there was clinical heterogeneity in terms of anti-VEGF treatment algorithms between the two RCTs. Further, longer prospective trials are required to provide insight into the effect size of specific treatment algorithms and patient outcomes. Additionally, capillary non-perfusion is one of the hallmarks of DR progression and neither of the trials in this review assessed the impact of anti-VEGF treatment on this important clinical biomarker of disease severity. aflibercept was the only anti-VEGF treatment that was assessed in this evidence synthesis, and it is uncertain how these results translate to other anti-VEGF agents. The literature was also lacking data on patient reported outcome measures and hence, no effect size could be estimated for this important outcome. There was also heterogeneity in terms of imaging modalities used to assess DRSS scores and retinal neovascularization and future studies should aim to standardise measurement for these outcome measures. Lastly, as noted above, many of the clinical variables synthesised in this review do not have an established clinical threshold for commencing intervention and there is also lack of cost analysis. Future work should also aim optimise potential regimens as the current ones designed for PDR and DMO may not be directly applicable to early stages of diabetic retinopathy.

Conclusion

Evidence supports the use of aflibercept treatment for management of patients with NPDR without CI-DMO. Effects include a regression of DRSS score and reduction in the risk of development of VTCs over 2 years. Future trials should assess long-term outcomes beyond year 2 as well as additional visual function outcomes and quality of life outcome measures that are lacking in this area.

Supplementary information

Author contributions

VC was responsible for study conception, design, interpretation of results and draft paper preparation. GSS was responsible for design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of results and draft paper preparation. DP, JX, MF were responsible for data collection. MRP, DZ were responsible for analysis and interpretation of results. LT, AL, FGH, SJG, PKK, MB, RHG, SFB, SS, CCW were responsible for interpretation of results, critical review and feedback on paper. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the paper.

Funding

This study represents original work never presented previously.

Competing interests

VC: Advisory board: Alcon, Roche, Bayer, Novartis; Grants: Bayer, Novartis. GSS: Nothing to disclose. MRP: Nothing to disclose. DP: Nothing to disclose. JX: Nothing to disclose. DZ: Nothing to disclose. MF: Nothing to disclose. LT: Nothing to disclose. AL: Consultant: Allergan, Bayer, BeyeOnics, ForSight Labs, NotalVision, Novartis, Roche. FGH: Research funds: Acucela, Allergan, Apellis, Bayer, Bioeq/Formycon, Roche/Genentech, Geuder, Heidelberg Engineering, IvericBio, Kanghong, Novartis, NightStarX, Zeiss; Personal fees: Boehringer-Ingelheim, Grayburg Vision, LinBioscience, Pixium Vision, Stealth BioTherapeutics, Aerie, Oxurion. SJG: Consultant: Allergan, Apellis, Bausch and Lomb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Johnson and Johnson, Kanaph; Research funds: American Academy of Ophthalmology, Apellis, Boehringer Ingelheim, NGM Bio, Regeneron. RHG: Advisory boards: Bayer, Novartis, Apellis, Roche, Genentech Inc. PKK: Consultant: Novartis, Bayer, Biogen, Regeneron, Kanghong, Allergan, RegenxBio. MB: Research funds: Pendopharm, Bioventus, Acumed. SF-B: Consultant: Allergan, Bayer, Novartis. SS: Research funds: Novartis, Bayer, Allergan, Roche, Boehringer, Ingelheim and Optos Plc; Travel grants: Novartis, Bayer; Speaker fees: Novartis, Bayer and Optos Plc.; Advisory board: Novartis, Bayer, Allergan, Roche, Boehringer, Ingelheim, Optos Plz, Oxurion, Ophthea, Apellis, Oculis, Heidelberg Engineering. CCW: Consultant: Acuela, Adverum Biotechnologies, Inc, Aerpio, Alimera Sciences, Allegro Ophthalmics, LLC, Allergan, Apellis Pharmaceuticals, Bayer AG, Chengdu Kanghong Pharmaceuticals Group Co, Ltd, Clearside Biomedical, DORC (Dutch Ophthalmic Research Centre), EyePoint Pharmaceuticals, Gentech/Roche, GyroscopeTx, IVERIC bio, Kodiak Sciences Inc, Novartis AG, ONL Therapeutics, Oxurion NV, PolyPhotonix, Recens Medical, Regeron Pharmaceuticals, Inc, REGENXBIO Inc, Santen Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd, and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited; Research funds: Adverum Biotechnologies, Inc, Aerie Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Aerpio, Alimera Sciences, Allergan, Apellis Pharmaceuticals, Chengdu Kanghong Pharmaceutical Group Co, Ltd, Clearside Biomedical, Gemini Therapeutics, Genentech/Roche, Graybug Vision, Inc, GyroscopeTx, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, IVERIC bio, Kodiak Sciences Inc, Neurotech LLC, Novartis AG, Opthea, Outlook Therapeutics, Inc, Recens Medical, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc, REGENXBIO Inc, Samsung Pharm Co, Ltd, Santen Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd, Xbrane Biopharma AB. No other acknowledgements to list.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41433-022-02269-y.

References

- 1.Brown DM, Schmidt-Erfurth U, Do DV, Holz FG, Boyer DS, Midena E, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept for diabetic macular edema: 100-week results from the VISTA and VIVID studies. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:2044–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heier JS, Korobelnik JF, Brown DM, Schmidt-Erfurth U, Do D V, Midena E, et al. Intravitreal Aflibercept for Diabetic Macular Edema: 148-Week Results from the VISTA and VIVID Studies. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:2376–85. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/27651226/. Accessed 27 Dec 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Sivaprasad S, Prevost AT, Vasconcelos JC, Riddell A, Murphy C, Kelly J, et al. Clinical efficacy of intravitreal aflibercept versus panretinal photocoagulation for best corrected visual acuity in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy at 52 weeks (CLARITY): a multicentre, single-blinded, randomised, controlled, phase 2b, non-inferiority trial. Lancet (London, England). 2017;389:2193–203. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/28494920/. Accessed 27 Dec 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Gross JG, Glassman AR, Jampol LM, Inusah S, Aiello LP, Antoszyk AN, et al. Panretinal photocoagulation vs intravitreous ranibizumab for proliferative diabetic retinopathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314:2137. 10.1001/jama.2015.15217. Accessed 27 Dec 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Sun JK, Glassman AR, Beaulieu WT, Stockdale CR, Bressler NM, Flaxel C, et al. Rationale and application of the protocol s anti-vascular endothelial growth factor algorithm for proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2019;126:87. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.08.001. Accessed 27 Dec 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Nguyen QD, Brown DM, Marcus DM, Boyer DS, Patel S, Feiner L, et al. Ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema: results from 2 phase III randomized trials: RISE and RIDE. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:789–801. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown DM, Nguyen QD, Marcus DM, Boyer DS, Patel S, Feiner L, et al. Long-term outcomes of ranibizumab therapy for diabetic macular edema: the 36-month results from two phase III trials: RISE and RIDE. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:2013–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt-Erfurth U, Garcia-Arumi J, Bandello F, Berg K, Chakravarthy U, Gerendas BS, et al. Guidelines for the Management of Diabetic Macular Edema by the European Society of Retina Specialists (EURETINA). Ophthalmologica. 2017;237:185–222. https://www-karger-com.login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/Article/FullText/458539. Accessed 27 Dec 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Anon. Diabetic Retinopathy PPP 2019—American Academy of Ophthalmology. https://www.aao.org/preferred-practice-pattern/diabetic-retinopathy-ppp. Accessed 27 Dec 2021.

- 10.Ehlers JP, Yeh S, Maguire MG, Smith JR, Mruthyunjaya P, Jain N, et al. Intravitreal pharmacotherapies for diabetic macular edema: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2022;129:88–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazhar K, Varma R, Choudhury F, McKean-Cowdin R, Shtir CJ, Azen SP. Severity of diabetic retinopathy and health-related quality of life: the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:649–55. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/21035872/. Accessed 2 Jan 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Gupta P, Aravindhan A, Gan ATL, Man REK, Fenwick EK, Mitchell P, et al. Association between the severity of diabetic retinopathy and falls in an Asian population with diabetes: The Singapore Epidemiology of Eye Diseases Study. JAMA Ophthalmology. 2017;135:1410. 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.4983. Accessed 28 Oct 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Anon. ICTRP Search Portal. https://trialsearch.who.int/?TrialID=EUCTR2007-006795-10-GB. Accessed 19 Oct 2021.

- 14.Lim JI. Prevention of severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy progression with more at stake than visual acuity. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021;139:714–6. https://jamanetwork-com.login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/journals/jamaophthalmology/fullarticle/2778075. Accessed 27 Oct 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Tinetti ME, Powell L. Fear of falling and low self-efficacy: a case of dependence in elderly persons. Journal of gerontology. 1993;48:35–8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8409238/. Accessed 28 Oct 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Anon. Fundus photographic risk factors for progression of diabetic retinopathy: ETDRS report number 12. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:823–33. http://www.aaojournal.org/article/S0161642013380142/fulltext. Accessed 27 Oct 2021. [PubMed]

- 17.Solomon SD, Chew E, Duh EJ, Sobrin L, Sun JK, VanderBeek BL, et al. Diabetic retinopathy: a position statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:412–8. https://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/40/3/412. Accessed 27 Oct 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Wong TY, Sun J, Kawasaki R, Ruamviboonsuk P, Gupta N, Lansingh VC, et al. Guidelines on diabetic eye care the international council of ophthalmology recommendations for screening, follow-up, referral, and treatment based on resource settings. Ophthalmology. 2018;1608–22. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.04.007. Accessed 27 Oct 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Nanegrungsunk O, Bressler NM. Prevention of vision-threatening complications in diabetic retinopathy: two perspectives based on results from the DRCR Retina Network Protocol W and the Regeneron-sponsored PANORAMA. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2021;32. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34419979/. Accessed 27 Oct 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Gross JG, Glassman AR, Liu D, Sun JK, Antoszyk AN, Baker CW, et al. Five-year outcomes of panretinal photocoagulation vs intravitreous ranibizumab for proliferative diabetic retinopathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136:1138–48. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30043039/. Accessed 27 Oct 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Mitchell P, McAllister I, Larsen M, Staurenghi G, Korobelnik JF, Boyer DS, et al. Evaluating the impact of intravitreal aflibercept on diabetic retinopathy progression in the VIVID-DME and VISTA-DME studies. Ophthalmology. Retina. 2018;2:988–96. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31047501/. Accessed 27 Oct 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Wykoff CC, Eichenbaum DA, Roth DB, Hill L, Fung AE, Haskova Z. Ranibizumab induces regression of diabetic retinopathy in most patients at high risk of progression to proliferative diabetic retinopathy. ophthalmology. Retina. 2018;2:997–1009. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31047503/. Accessed 27 Oct 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Bressler SB, Liu D, Glassman AR, Blodi BA, Castellarin AA, Jampol LM, et al. Change in diabetic retinopathy through 2 years: secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial comparing aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135:558–68. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28448655/. Accessed 27 Oct 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Sivaprasad S, Prevost AT, Vasconcelos JC, Riddell A, Murphy C, Kelly J, et al. Clinical efficacy of intravitreal aflibercept versus panretinal photocoagulation for best corrected visual acuity in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy at 52 weeks (CLARITY): a multicentre, single-blinded, randomised, controlled, phase 2b, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2193–203. http://www.thelancet.com/article/S0140673617311935/fulltext. Accessed 27 Oct 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Alagorie AR, Velaga S, Nittala MG, Yu HJ, Wykoff CC, Sadda SR. Effect of aflibercept on diabetic retinopathy severity and visual function in the RECOVERY study for proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmol Retin. 2021;5:409–19. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2020.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown DM, Wykoff CC, Boyer D, Heier JS, Clark WL, Emanuelli A, et al. Evaluation of intravitreal aflibercept for the treatment of severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy: results from the PANORAMA randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021;139:946–55. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34351414/. Accessed 19 Oct 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Maturi RK, Glassman AR, Josic K, Antoszyk AN, Blodi BA, Jampol LM, et al. Effect of intravitreous anti-vascular endothelial growth factor vs sham treatment for prevention of vision-threatening complications of diabetic retinopathy: the Protocol W randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021;139:E1–2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33784735/. Accessed 19 Oct 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Anon. Grading diabetic retinopathy from stereoscopic color fundus photographs—an extension of the modified airlie house classification: ETDRS report number 10. Ophthalmology. 2020;127:S99–119. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.3 (updated September 2020). Cochrane, 2020. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

- 30.Anon. RoB 2: a revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials | Cochrane Bias. https://methods.cochrane.org/bias/resources/rob-2-revised-cochrane-risk-bias-tool-randomized-trials. Accessed 19 Oct 2021.

- 31.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Schünemann HJ, Tugwell P, Knottnerus A. GRADE guidelines: a new series of articles in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:380–2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21185693/. Accessed 19 Oct 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Anon. 9.5.2 Identifying and measuring heterogeneity. https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/chapter_9/9_5_2_identifying_and_measuring_heterogeneity.htm. Accessed 22 Dec 2021.

- 33.Anon. Long-term efficacy and safety of intravitreal aflibercept injections for the treatment of diabetic retinopathy for subjects who completed the 2-year PANORAMA trial—full text view—ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04708145. Accessed 19 Oct 2021.

- 34.Anon. Intravitreal bevacizumab for nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy—full text view—ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04511715. Accessed 19 Oct 2021.

- 35.Anon. A multicenter, randomized study in participants with diabetic retinopathy without center-involved diabetic macular edema to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics of ranibizumab delivered via the port delivery system relative to the comparator Arm—Full Text View—ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04503551. Accessed 19 Oct 2021.

- 36.Anon. China Clinical Trial Registration Center-Level 1 Registration Body of the World Health Organization International Clinical Trial Registration Platform. https://www.chictr.org.cn/showproj.aspx?proj=16494. Accessed 19 Oct 2021.

- 37.Anon. Multicenter Clinical Study of Anti-VEGF Treatment on High Risk Diabetic Retinopathy (DR)—Full Text View—ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03452657. Accessed 19 Oct 2021.

- 38.Anon. ICTRP Search Portal. https://trialsearch.who.int/?TrialID=EUCTR2011-003304-20-GB. Accessed 19 Oct 2021.

- 39.Anon. Evaluation of the retina in patients with non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy after aflibercept injection in the eye—full text view—ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04702048. Accessed 19 Oct 2021.

- 40.Ip MS, Zhang J, Ehrlich JS. The clinical importance of changes in diabetic retinopathy severity score. Ophthalmology. 2017;124:596–603. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28284785/. Accessed 14 Nov 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.