Abstract

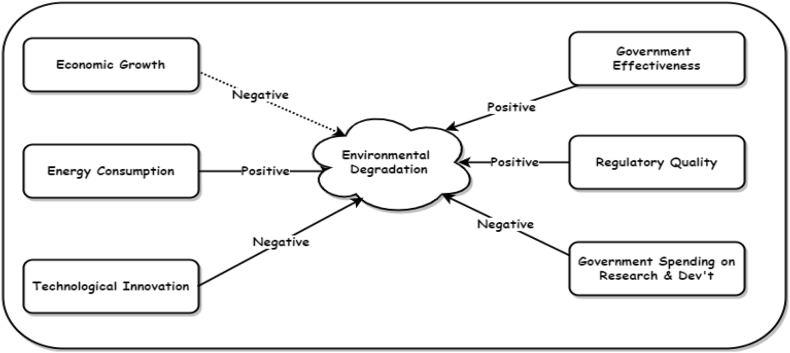

The study explores the interaction between regulatory quality, economic growth, technological innovation, energy consumption, government spending on research and development, and environmental degradation (EVD) in the Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa (CEMAC) region. The study applied the econometric approach CS-ARDL to estimate the short and long-term interaction between the regressors and the explanatory variable. The study period covers from 1990 to 2020. To summarize the findings of this research, (1) the study discovered a positive relationship between energy consumption, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, and environmental degradation. (2) Economic growth, government spending on research and development, and technological innovation, on the other hand, extensively dissipates EVD in the CEMAC economies. (3) The causality analysis espoused a bidirectional connection between energy consumption, technological innovation, and EVD. (4) Lastly, a unidirectional interplay exists between economic growth, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, and EVD. This study also serves as a reference point for policymakers and governmental institutions to invest in cleaner technologies and increase government research and development spending to mitigate environmental degradation in these areas.

Keywords: Economic growth, Technological innovation, Regulatory quality, Government effectiveness, Energy consumption

1. Introduction

Macroeconomic factors and environmental degradation (EVD) have been widely debated over two decades. Meanwhile, emerging and developed economies have experienced global warming [1]. The emerging nations of the Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa (CEMAC) are expanding in their economic growth. Substantial global economic and political adjustments have occurred in the CEMAC nations during the past decade [2]. The CEMAC comprises six economies: Equatoria Guinea, Chad, Central Africa Republic, Cameroon, Gabon, and the Republic of Congo [3]. stipulated that these countries rely heavily on livestock, agriculture, and fossil fuel as their main source of economic expansion. The dependence on these resources has led to an increase in EVD. For example, Equatorial Guinea emitted more than 15 million tonnes of carbon emission, constituting almost 0.03% of worldwide emissions in 2019 [4]. Chad also emitted more than 105 million, equivalent to 0.21 of global pollution. The Central Africa Republic produced more than 46 million tonnes of emission. Cameroon had the highest rate of emission among the CEMAC region with the country emitting approximately 0.25% (more than 124 million of tonnes) of global pollution. Gabon produced more than 19 million tonnes and the Republic of Congo emitted more than 30 million tonnes of CO2 [4]. This trend analysis indicates that the level of EVD in these countries are upsurging and it require proper mechanism to neutralize this menace.

From a pragmatic perspective, the CEMAC states represent a particularly intriguing area of inquiry since the economic growth (EGC) and energy consumption (ENC) of these countries have increased exponentially, which has led to a higher level of ecological challenges [5]. Moreover, despite the numerous empirical analyses conducted from different economic blocks [[6], [7], [8]] a literature gap on factors that affect environmental pollution in the CEMAC regions. Therefore, it is critical to fill this literature gap and find a solution to this menace to help the CEMAC economies reach environmental targets stipulated by the United Nations and the Paris agreement [2,9].

This study is crucial because it provides recommendations for policymakers and other stakeholders in the CEMAC economies on how to promote and carry out ecological stability policies that will lessen EVD in these regions. The current research extended the Stochastic Impacts by Regression on Population, Affluence, and Technology (STIRPAT) and Environment Kuznets Curve (EKC) by evaluating the effect of economic growth, energy consumption, and technological innovation on EVD in the CEMAC countries. In addition, the study explores the influence of government effectiveness (GE), regulatory quality (RQ), and government spending on research and development (GSRD) on the level of EVD in these regions.

EGC and EVD reduction are mutually reinforcing objectives for national and international low-carbon pathways [10]. Because greenhouse gas emissions contribute to global climate change, ENC and carbon dioxide emissions are a seriously concerned, especially in the CEMAC region [3,11]. Similarly, in most of these CEMAC countries, non-renewable sources of energy are the main mechanism for promoting the manufacturing of goods and services. In addition [12], asserted that CO2 emissions are the major byproduct of burning coal, contributing to about 42% of global emissions. The CEMAC states need to reduce their reliance on ENC, such as coal, invest in renewable ENC, and strengthen their environmental policies. Extant studies have also proven that over-reliance on non-renewable ENC can lead to the deterioration of the environment [[13], [14], [15]].

Moreover, the effect of TI on EVD has garnered considerable interest from environmental experts [16]. believe that one common trait of emerging economies is the reliance on outdated technology, which causes a rise in global warming and EVD, for which the CEMAC nations have been affected by this trend. It has been discovered by extant studies that the effective use of TI is critical for the expansion of green economies and also serves as a mitigating tool for EVD [[17], [18], [19]]. Therefore, it is essential to evaluate the impact of TI on EVD from the CEMAC economies. Regulatory quality (RQ) and government effectiveness (GE) are critical for conserving environmental quality and the efficient utilization of available natural resources needed for sustainable development [[20], [21], [22]]. The sustainability of natural resources and the conservation of the environment are linked to the RQ and GE [23]. As enunciated by Ref. [5], the assertion that the CEMAC states have to practice political pluralism to promote their governance system indicates a bright spot for these nations. Thus, the shift away from one party state has necessitated financial and economic reforms to strengthen RQ and GE, which should encourage greater environmental conservation policies and programs [5]. Hence, this research evaluates the influence of GE and RQ on EVD in the CEMAC states.

Government spending on research and development (GSRD) is another essential factor influencing environmental stability. The current EVD levels call for governments to provide financial assistance for research into new EVD transition channels and mechanisms to suggest plans and policies to mitigate the negative impact of climate change in the CEMAC countries. Hence previous studies have established that higher investment in GSRD promotes environmental stability [[24], [25], [26], [27]]. Consequently, this study also evaluated the influence of GSRD on EVD in the CEMAC nations. Hence, this research seeks to answer the following questions: (1) Does EGC, TI, and GSRD dispel EVD in the CEMAC region? (2) Does RQ, GE and ENC cause environmental havoc in these emerging economies? (3) What is the causality association among these variables, and what measures should stakeholders take to abate EVD issues in the CEMAC countries?

The present study contributes to extant literary works in four stringent ways: First, by providing an empirical analysis of the effect of TI, ENC, and EGC on EVD, this research expands the environment and energy research in the CEMAC region. Second, this analysis adds to erstwhile studies [2,3,16] by incorporating new variables such as RQ, GE, and GSRD as triggers of EVD for the CEMAC nations from 1990 to 2020. Third, the research provides practical recommendations based on the study's findings. The research recommendations offer practical strategies that governments, policy planners, environmental scientists, and scholars can utilize to help curb and mitigate the high level of ecological destruction in these countries. Lastly, this study used the latest and modern econometric approach to estimate the long-term interplay among the series under consideration. Thus, the empirical approach factored in significant steps, which include; (i) cross-sectional dependency test (CSD), (ii) slope heterogeneity test, (iii) cointegration analysis and cross-sectional autoregressive distributed lag (CS-ARDL) estimation approach the long and short run integration between the independent parameter and the explanatory parameter. (iv) The analysis further used the fully modified ordinary least square (FMOLS) and dynamic ordinary least square (DOLS) as the robustness evaluation of the CS-ARDL approach. (v) The [28] (D-H) causality test was applied to assess the causality connection among the study parameters.

The research is organized as follows in its entirety. Section 2 of this study contains a review of recent literary works. The theoretical context, data, and econometric strategy used in this study are described in Section 3. The empirical findings and discussion are covered in Section 4 of this study. The summary in Section 5 summarizes the study's findings as well as its theoretical and applied implications.

2. Literature review

2.1. Theoretical background

When evaluating the parameters affecting EVD, it is essential to examine the association between EGC and pollution. Hence the EKC hypothesis suggested by Ref. [29] describes the nonlinear linkage between EGC and ECD. The EKC theory asserts that growth may cause higher emissions at lower income levers and lesser pollution at higher income levels [30]. This situation can lead to a U-shaped association between income levels and EVD. Most studies have evaluated or validated whether EVD increases or declines in economies with upsurging EGC within the EKC hypothesis [23,31]. The concurrent deployment of the EKC theory in several environmental research underlines the importance of this concept in the formation of national green policies [[32], [33], [34]]. Thus, the EKC model contends that because a higher level of EGC results in the utilization of more consumption of raw materials, energy, and natural resources, they significantly contribute to ecological devastation. Contrastingly, wealth expansion surpassing a benchmark or threshold contributes to the decline in EVD as individuals and organizations become more conscious of the issues with EVD and hence establish effective pollution laws [1,23,35]. Several environmental studies have investigated the ECK model. For instance Ref. [36], for BRICS economies [37], for 54 Africa Union economies [38], for Gulf Corporation Council (GCC). In addition to the ECK theory, the research further incorporated the STIRPAT model to examine the influence of technological innovation, regulatory quality, and GSRD on EVD in the CEMAC economies. The next section of this chapter discusses empirical studies that evaluated the association between variables such as EGC, ENU, and EVD. In addition, the connection between TI-EVD, RQ-EVD, GE-EVD, and GSRD-EVD has been discussed. Some empirical studies that have evaluated the association between EGC-ENC-EVD have been summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of related studies.

| Authors | Time Frame | Indicators Used | Economy | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [39] | 1990–2013 | EVD, EGC, ENC | MINT | EGC EVD () |

| ENC EVD () | ||||

| [40] | 1971–2014 | EVD and EGC | Pakistan | EGC EVD () |

| [41] | 1984–2016 | EVD and EGC | Emerging Economies | EGC EVD () |

| [42] | 1995–2016 | EVD, EGC, ENC | ASEAN | EGC EVD () |

| ENC EVD () | ||||

| [43] | 1971–2017 | EVD, EGC and ENC | MINT | EGC EVD () |

| ENC EVD () | ||||

| [44] | 1990–2016 | EVD, EGC, and ENC | South Asian | EGC EVD () |

| ENC EVD () | ||||

| [45] | 1990–2015 | EVD, EGC, and ENC, | G7 economies | EGC EVD () |

| ENC EVD () | ||||

| [46] | 1971–2016 | EVD and ENC | China and Brazil | ENC EVD () |

| [2] | EVD, EGC and RQ | CEMAC | EGC EVD () | |

| RQ EVD () | ||||

| [15] | 1990–2018 | EVD, EGC, and ENC | BRICS-T | EGC EVD () |

| ENC EVD () | ||||

| [47] | 1983–2017 | EVD, EGC, and ENC | Brazil | EGC EVD () |

| ENC EVD () | ||||

| [3] | 1980–2018 | EVD and EGC | CEMAC | EGC EVD () |

| [48] | 1980–2017 | EVD, EGC, ENC | USA | EGC EVD () |

| ENC EVD () | ||||

| [49] | 1990–2017 | EVD, ENC and TI | China | TI EVD |

| ENC EVD () | ||||

| [16] | 1960–2014 | EVD, EGC, and ENC | CEMAC | EGC EVD () |

| ENC EVD () | ||||

| [19] | 1990–2020 | EVD, EGC, ENC | MINT | EGC EVD () |

| ENC EVD () | ||||

| [50] | 1960–2020 | EVD, EGC, and ENC | South Africa | EGC EVD () |

| ENC EVD () | ||||

| [51] | 1984–2017 | EVD, EGC, and ENC, | G11 economies | EGC EVD () |

| ENC EVD () |

Note: EVD = Environmental degradation (CO2 emission and ecological footprint) ENC= (Renewable and Non-renewable energy sources), EGC = Economic growth (GDP),TI= Technological Innovation, MINT = Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria and Turkey, Positive association, negative association.

2.2. Economic growth, energy consumption, and environmental degradation nexus

The examination of the ENC-EGC-EVD dilemma has been ramified over the last decades, dividing environmental research on this topic into two phases. The first stream of research evaluated the connection between EVD and EGC through the EKC and the STIRPAT model established by Refs. [11,29,52,53]. The underlying assumption of these theories is that while an economy first flourishes at the expense of EVD, this trade-off progressively lessens as advanced stages of industrial growth support environmental progress. Several studies in recent times have applied the STIRPAT approach and EKC in evaluating the ecological impact of technology, population, affluence, and other variables on environmental degradation from different jurisdictions [[54], [55], [56]]. The second stream of studies also has documented that higher environmental pollution results from emissions from ENC, such as coal, natural gas, and fossil fuel, for economic development [23,57]. ENC is anticipated to cause an upsurge in the activities of manufacturing industries which will accelerate EGC. Hence the increased demand for ENC could influence EVD. This is because burning coal releases greenhouse gas which is deemed to be damaging to the sustainability of the environment [50,58,59].

2.3. Technological innovation and environmental degradation nexus

The existing studies on the TI-EVD nexus have resulted in conflicting outcomes. While some authors argue that the effective use of TI reduces EVD, other schools of thought have established that TI has a detrimental influence on EVD. For instance Ref. [18], explored the connection between TI-EVD by applying a panel dataset from 1980 to 2018. The empirical findings from their research proved that environmental sustainability could be achieved by using TI for economic development in Malaysia. Likewise [60], also established in their research that the higher level of environmental destruction could be corrected with the advancement in TI in the BRICS economies. In addition [61], explored the interplay between TI-EVD and reported that TI improves ecological stability. Similarly, the study by Ref. [62] for European Union economies [19], for Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria, and Turkey (MINT) [63], for South Africa have empirically proposed that the progression of TI has helped improve ecological stability in these regions. Nevertheless, the empirical findings from Ref. [64] for BRICS [17] for Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) [49] found that TI impedes ecological stability. In conclusion, given that the literature has not yet come to a resolution, it may be analyzed the effects of TI on EVD have yielded contradictory outcomes.

2.4. Regulatory quality and environmental degradation nexus

A theory propounded by Ref. [65] pointed out that EVD may be associated with the effectiveness and efficiency of regulatory and institutions linked to legal mechanisms for supervising, evaluating, and enacting compliance requirements [66]. argued that economies that develop precise regulations and guidelines regarding permit issuance, taxation, and charges on fees could expect enterprises to follow the regulatory framework regarding production and firm waste management systems. Furthermore [66], reported that it is theoretically proven that RQ increases EXP, which is likely to impact EVD [67]. confirmed in their research that RQ and policies help improve environmental degradation. In Saudi Arabia [68], reported a significant and adverse impact of RQ on EVD. Their study recommends that it is essential to improve RQ and ensure that enterprises follow these regulations to help eradicate environmental degradation [22]. reported that RQ caused an upsurge in renewable and non-renewable energy use among the South Asia economies.

2.5. Government effectiveness and environmental degradation nexus

Government effectiveness (GE) is very vital in controlling environmental degradation. Thus GE may include bureaucratic system and inefficiencies, the perception of poor governance, mismanagement of funds within the public sector, and specifically ineffective government environmental control mechanism [22,66]. Few studies have examined the nexus between GE and EVD, especially among the CEMAC economies. However, some studies have reported on the relationship among these variables. For instance Ref. [69], examined the connection between GE and EVD among emerging and developing economies. Their outcome found that GE modifies the relationship between economic growth and environmental degradation [70]. found evidence from the Sub-Saharan countries on the impact of GE on EVD. Their outcome indicated that GE has a negative relationship with environmental degradation. This implies that GE can help dissipate EVD in the BRICS countries [71]. believes that GE supports environmentally friendly initiatives, which impact EVD.

2.6. Government spending on research and development and environmental degradation nexus

Recent literature has found conflicting results on GSRD-EVD [26]. analyzed the impact of GSRD on EVD in the G7 nations with panel data from 1870 to 2014. Their study's outcome indicated that GSRD affects the level of EVD in both positive and negative ways. Thus, GSRD affected EVD through a simultaneous effect on ENC and EGC [72]. also examined the impact of GSRD on EVD using panel data from 1990 to 2013, with the primary focus on justifying GSRD in the context of mitigating EVD. Their findings proved that GSRD contributes to the reduction of EVD. Using panel data from 1990 to 2016 [73], analyzed the nexus between GSRD among the Mediterranean economies. According to their research outcome, GSRD has an adverse and unidirectional impact on EVD. Among the OECD economies [24], findings point out a negative and long-run association between GSRD and EVD. Their research further indicated that an increase in the investment in GSRD would influence a reduction in EVD in the OECD countries. Contrary to this outcome, studies by Ref. [74] found that GSRD increases EVD.

3. Methodology

3.1. Variable definition and unit of measurement

Environmental Degradation (EVD): The explanatory parameter in this study is EVD, which is approximated by the CO2 emissions of the countries within the study period (1990–2020). The study measures CO2 in kilo tones, which has been used in several studies [[75], [76]].

Economic growth (EGC): was assessed with the annual economic performance of the CEMAC economies based on the gross domestic product (GDP). Several studies have proven the increase in EGC to positively connect with a higher level of EVD [63,77,78]. Hence in this research, we expect a positive nexus between EGC-EVD.

Energy Consumption (ENC): The estimation of ENC was based on the use of non-renewable energy in the countries under investigation in this research. Thus, ENC was measured with a kilogram of oil equivalent per capita assessed in these studies [7,[79], [80]]. As a result, this study posits a positive association between ENC-EVD.

Technological Innovation (TI): [81] argues that countries can reach carbon neutrality if they invest in technology and innovation. This research focuses on the number of patent applications authorized in a particular country as a measure for TI. Since extant studies have proved that TI can be harnessed to improve environmental sustainability [47,82], this study anticipates an inverse interplay between TI-EVD.

Regulation quality (RQ): This study measures RQ as the government's capability and capacity to initiate policies, plans, and effective regulations that promote and enhance the private sector to develop and contribute to society's advancement. We expect that if there is an effective RQ in the selected countries, it can reduce EVD. Studies by Ref. [83] employed this variable in their analysis.

Government Effectiveness (GE): estimates a country's public services quality, the degree of government independence from a civil group or political pressures, the formulation and implementation of quality plans and policies, and the government's total commitment to such policies to develop the country. Adding such an essential variable in our study is because we assume that an effective government will have a higher responsibility toward carbon neutrality.

Government spending on research and development (GSRD): is vital in the fight against climate change. In this research, GSRD is measured as a total expenditure (current and capital) on research and development carried out by enterprises, research organizations, government research groups, and various universities in a particular country at a point in time [24]. This variable is measured in research and development by %$US (constant USD 2010).

3.2. Data source

The data used to measure EVD, ENC, EGC, and GSRD was collected from World Development Indicator [84], while the dataset for TI was retrieved from Ref. [85]. The data for RQ and GE were obtained from Worldwide Governance Indicator [86]. Table 2 captures the description and unit of measurement for all the study parameters. The analysis of this study was utilized with the social science statistical tool (EVIEWS).

Table 2.

Synopsis of the variable description.

| Variable | Symbols | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Degradation | EVD | CO2 emissions in kilo ton (kt) | WDI |

| Energy Consumption | ENC | Energy Usage (kg of oil equivalent per capita | WDI |

| Economic Growth | EGC | Per Capita (constant USD $2010) | WDI |

| Technological Innovation | TI | No. Of patent applications authorized by both resident and non-resident | OECD |

| Regulatory Quality | RQ | Estimates Government effective regulations | WGI |

| Government Effectiveness | GE | Estimates on public services quality | WGI |

| Government spending on research and development | GSRD | R&D measured by %$US (constant $2010) | WDI |

Note: WDI: World Development Indicators, WGI: World Governance Indicators, OECD: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development EGC-Economic Growth, ENC-energy consumption, RQ-Regulatory quality), GE-Government effectiveness, and GSRD-Government spending on research and development.

3.3. Econometric estimation approach

The empirical and theoretical basis for choosing the explanatory parameters of this research can be aligned with the theoretical foundation, which includes the STIRPAT [52]. For the STIRPAT model, Stochastic Impacts, I denote the environmental Impacts, P indicates population, A shows a country's affluence, and T depicts environmental technology. Based on this notion, this study incorporated EGC, ENU, TI, RQ, GE, and GSRD to evaluate their impact on EVD. Similar research analyzing these variables and their effect on EVD through the STIRPAT theory includes [17,54,87]. Hence the STIPAT is mathematically expressed in equation (1) as:

| (1) |

Such that I represent EVD, which is influenced by population (P), affluence (A), and technology (T). The elasticity of the model is indicated with the terms . The error term is identified by and i symbolize the individual countries under investigation in this research and signifies the period of the study. Based on the STIRPAT model and extant studies [17,54,87], the study incorporated the parameter and proposed equation (2):

| (2) |

such that InEVD (Environmental degradation), InEGC (Economic Growth), In InENC (energy consumption), InRQ (Regulatory Quality), InGE (Government effectiveness), and InGSRD (Government spending on research and development) are represented in their natural logarithm forms. The elasticity of the model is indicated with the terms . The error term is identified by and i symbolize the individual countries under investigation in this research. signifies the period of the study (1990–2020).

3.3.1. Cross-sectional dependence test

To ascertain any cross-sectional dependency (CSD) issues in the data parameters, the study applied three estimation approaches: Breusch-Pagan LM, Pesaran scaled LM, and Pesaran CD, as suggested by Ref. [88]. Previous studies have established that the presence of CSD in the data may result in erroneous conclusions [89,90]. Equation (3) indicates the mathematical formulae for the CSD test.

| (3) |

where T symbolizes the cross-sections between the measurements, stands for correlation residuals of the calculated model, and N represents the period.

3.3.2. Slope homogeneity test

After assessing the CSD [91], added that the panel data should be devoid of heterogeneity issues since it might lead to an inaccurate outcome. Hence to account for the homogeneity, the study employed a methodology espoused by Ref. [92] to evaluate the slope homogeneity across the panel data sets, which is provided in equations (4), (5)):

| (4) |

| (5) |

where SHT identifies the delta of the SH and stands for the adjusted SH.

3.3.3. Unit root test

The second-generational panel unit root test was also used to determine the degree of stationarity among the series. The investigation used the Cross-sectional Augmented Dickey-Fuller (CADF) and the Cross-sectional I'm Pesaran and Shin models (CIPS). These two-panel data stationary tests (CADF and CIPS) have given more precise estimations than the first-generation unit root test in previous literary works [1,93]. The mathematical formulae for these tests are specified in equations (6), (7)

| (6) |

where demonstrates disparities between the variables, implies parameters analyzed in the study, and the error term of the model is indicated with .

| (7) |

where T depicts the cross-sections among the parameters and N shows the period.

3.3.4. Cointegration approach

In panel data analysis, it is imperative to evaluate the existence of cointegration among the parameters. As a result, the study employed the Johanson-Fisher [94,95] cointegration approaches to estimate the presence of long-term association among the series. The Johansen cointegration test provided two categories: Max-Eigen and Trace. The specification of the null hypothesis is the basic statistical distinction between this cointegration assessment. The Johanson-Fisher cointegration analysis has the advantage of offering alternate cointegrating among panel datasets. In addition to the Johansen Cointegration approach, the study used the [96] estimation technique. Prior studies have demonstrated that this technique resolves CSD issues and produces accurate outcomes for estimating long-term interaction among panel series [56,97]. The mathematical representation for the four tests of this [96] cointegration analysis is presented in equations (8), (11a), (11b):

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11a) |

such that and represent the panel statistics and and identify the group means statistics. The speed of movement from the long-term co-efficient is defined with .

3.3.5. Estimation of long-run elasticity

After establishing the long-term cointegration among the study's variables, the analysis employed the CS-ARDL technique to assess the long- and short-term association among the study variables. Erstwhile studies have demonstrated that this estimation method produces a dependable, accurate, and robust outcome in panel data analysis [98]. In addition, the CS-ARDL overcomes the challenges and issues of panel data, such as CSD, multicollinearity, and dynamic panel disparities [51,60,90]. The equation for this procedure is as follows:

| (11b) |

where = shows the CSD averages and denotes regressors in the research model (EGC, ENU, TI, RQ, GE, and GSRD).

3.3.6. Robustness analysis

The study applied the fully-modified ordinary least square FMOLS and DOLS to evaluate the robustness of the CS-ARDL approach [99]. The fundamental reason for selecting this econometric approach is that the FMOLS factor in the issues of slope heterogeneity across the panel data section. Moreover, this technique produces a precise and accurate outcome, as indicated by previous studies [58,100,101]. Additionally, these methods aid in eradicating serial correlation, heteroscedasticity, and endogeneity [37]. To evaluate the robustness of the FMOLS, we employed the dynamic ordinary least square (DOLS) suggested by Ref. [102]. Equations (12), (13) provide the mathematical expressions for the FMOLS and DOLS models, respectively.

| (12) |

| (13) |

3.3.7. Causality analysis

The CS-ARDL, FMOLS, and DOLS provide information explaining the long-run dynamics connection of the parameter; however, these approaches cannot disclose information on the causality between the series. Hence to verify the causality between EVD, EGC, ENC, TI, RQ, GE, and GSRD, the Dumitrescu and Hurlin (D-H) test was selected to evaluate the causality test [28]. Equation (14) analytically illustrates the D-H non-causality assessment:

| (14) |

where displays the model's autoregressive properties with specifying the lag's duration.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Descriptive statistics

The descriptive statistics and correlation matrix for the series are presented in Table 3. The mean, standard deviation, and minimum and maximum statistics have been provided for all the series. The correlation matrix shows a positive correlation between InENC, InEGC, InTI, and InGSRD. On the other hand, InRQ has an inverse association with EVD. Correlations can be used to draw certain conclusions, but not enough. More econometric analyses are performed as a result. In addition, the multicollinearity of the variables is evaluated using the variance inflation factor (VIF) approach. According to the results of the VIF test, all statistical values were below the cutoff point of 10 suggested by Refs. [103,104], demonstrating the falsity of the multicollinearity issue with the study model.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics, correlation matrix, and VIF.

| Variables | Mean | Std.Dev | Maximum | Maximum | VIF | Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| InEVD | 6.010 | 0.867 | 7.748 | 5.267 | 2.364 | |

| InEGC | 5.186 | 0.515 | 6.778 | 4.477 | 3.055 | 0.583*** |

| InENC | 7.714 | 0.856 | 5.413 | 1.880 | 2.380 | 0.198*** |

| InGE | 3.956 | 0.335 | 4.466 | 2.467 | 1.457 | 0.441*** |

| InRQ | 3.815 | 0.494 | 4.395 | 0.218 | 1.035 | −0.202*** |

| InTI | 8.958 | 0.503 | 14.147 | 4.927 | 2.032 | 0.373*** |

| InGSRD | 3.138 | 0.397 | 9.249 | 1.342 | 2.859 | 0.698*** |

Note: *** indicates a 1% significance level. EVD-Environmental degradation- EGC-Economic Growth, ENC-energy consumption, RQ-Regulatory quality), GE-Government effectiveness, and GSRD-Government spending on research and development.

4.2. Cross-sectional dependence test and slope homogeneity outcome

The outcome of all the CSD and tests of slope homogeneity are summarized in Table 4. The study's outcome unveiled that at a 1% statistical significance level, all the test statistics reject the null hypothesis of cross-sectional independence to affirm CSD among the research variables. Thus, the result proved that proof that any changes to one economy within the panel would also affect the other countries in the CEMAC block. In addition, in Table 4, and adjusted indicates the statistical test for slope homogeneity and the biased adjusted components. The outcome of the SHT analysis provides us with enough and sufficient evidence for the prevalence of economic interdependence in the study proposed model.

Table 4.

Outcome of CSD test and Test of slope homogeneity.

| Series | Bias-Corrected Scaled LM | Pesaran scaled LM | Breusch-Pagan LM |

|---|---|---|---|

| InEVD | 194.703*** | 41.300*** | 7.1472*** |

| InEGC | 172.964*** | 36.439*** | 10.071*** |

| InENC | 53.372*** | 9.698*** | 6.317*** |

| InGE | 116.433*** | 23.799*** | 9.936*** |

| InRQ | 72.991*** | 14.085*** | 2.228*** |

| InTI | 79.434*** | 15.525*** | 5.573*** |

| InGSRD | 101.034*** | 20.355*** | 9.211*** |

| Test of slope homogeneity | |||

| 14.023*** | |||

| 14.538*** | |||

Note: *** indicates a 1% significance level. EVD-Environmental degradation- EGC-Economic Growth, ENC-energy consumption, RQ-Regulatory quality), GE-Government effectiveness, and GSRD-Government spending on research and development.

4.3. Unit root test outcome

Table 5 displays the results of the second generational panel unit root test- CIPS and CADF for examining the stationarity of the series. The outcome indicated that all the study parameters (InEVD, InEGC, InENC, InTI, InRQ, InGE, and InGSRD) were non-stationary; nevertheless, after the first difference test, all the series became stationary I (1). The establishment of stationarity among the series denotes a possibility of long-term connection among the study variables.

Table 5.

Outcome of panel unit root test.

| Variables | CADF |

CIPS |

Decision | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | First difference | Level | First difference | ||

| InEVD | 1.0628 | −9.615*** | −1.181 | −8.274*** | (1) |

| InEGC | 2.0490 | −7.852*** | 1.691 | −4.338*** | (1) |

| InENC | 0.2533 | −5.972*** | 1.164 | −12.107*** | (1) |

| InGE | 0.1282 | −9.077*** | −2.169 | −13.052*** | (1) |

| InRQ | 0.9041 | −8.625**** | −0.740 | −11.342*** | (1) |

| InTI | 2.1021 | −5.309*** | 0.229 | −8.495*** | (1) |

| InGSRD | 0.9261 | −6.691*** | −0.826 | −7.998*** | (1) |

Note: *** indicates a 1% significance level. EVD-Environmental degradation- EGC-Economic Growth, ENC-energy consumption, RQ-Regulatory quality), GE-Government effectiveness, and GSRD-Government spending on research and development.

4.4. Panel cointegration test outcome

The result for the two cointegration tests is displayed in Table 6. First, the results of [94]- Johansen's cointegration test indicated that both Max-Eigen and Trace tests confirm the long-run equilibrium link between the series. Moreover, the [95] results confirm that environmental deterioration in the CEMAC nations has long-term interaction with InEVD, InEGC, InENC, InTI, InRQ, InGE, and InGSRD. The outcome of the [96] cointegration test revealed all the parameters evaluated in this study were cointegrated. Hence the study can estimate the short and long-term interaction among the study parameters.

Table 6.

Outcome of panel cointegration test.

| Cointegration Construct | Fishers Stats* (Trace Test) | Fisher Stat* (Max-Eigen Test) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Johansen Cointegration Test | ||||

| None | 674.2*** | 175.7*** | ||

| At most 1 | 275.0*** | 173.5*** | ||

| At most 2 | 212.4*** | 103.7*** | ||

| At most 3 | 130.1*** | 57.69*** | ||

| At most 4 | 85.71*** | 39.15*** | ||

| At most 5 | 55.01*** | 36.83*** | ||

| At most 6 | 28.90 | 25.69 | ||

| At most 7 | 18.20 | 17.10 | ||

| Kao, (1999) Cointegration Test | [96] | |||

| Test Stats | Z-value | P-value | ||

| ADF- test | −5.087*** | 8.314*** | 0.000 | |

| 1.026 | 0.673 | |||

| 6.074*** | 0.000 | |||

| 0.973 | 0.885 | |||

Note: Note: *** indicates a 1% significance level.

4.5. Short and long-run estimation outcome

The long and short-run estimates for both the CS-ARDL are presented in Table 7 and Fig. 1. The research applied FMOLS and DOLS as the robustness test for the CS-ARDL, and the results are shown in Table 8.

Table 7.

Outcome of Short and long-run elasticities (CS-ARDL).

| Series | Coefficient | Std. Error | T-value | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long-term elasticity | ||||

| InEGC | −0.572*** | 0.121 | −6.390 | 0.000 |

| InENC | 0.754*** | 0.017 | 8.482 | 0.000 |

| InGE | 0.327*** | 0.182 | 4.893 | 0.000 |

| InRQ | 0.215*** | 0.109 | 3.535 | 0.001 |

| InTI | −0.184*** | 0.016 | −4.835 | 0.002 |

| InGSRD | −0.452*** | 0.084 | −7.951 | 0.000 |

| Short-term elasticity | ||||

| InEGC | −0.690*** | 0.027 | −9.367 | 0.000 |

| InENC | 0.436*** | 0.194 | 6.748 | 0.000 |

| InGE | 0.830*** | 0.384 | 9.732 | 0.000 |

| InRQ | 0.270** | 0.063 | 5.736 | 0.001 |

| InTI | −0.504*** | 0.075 | −7.316 | 0.000 |

| InGSRD | −0.721*** | 0.320 | −9.002 | 0.000 |

| ECT (−1) | −0.844*** | −8.634 | ||

| R2 | 0.98 | |||

| Adj R2 | 0.96 | |||

Note: *** indicates a 1% significance level. EVD-Environmental degradation- EGC-Economic Growth, ENC-energy consumption, RQ-Regulatory quality), GE-Government effectiveness, and GSRD-Government spending on research and development.

Fig. 1.

Graphical representation of empirical results.

Table 8.

Outcome of the robustness check (FMOLS and DOLS).

| Variables | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FMOLS estimates | ||||

| InEGC | −0.428*** | 0.012 | −10.802 | 0.001 |

| InENC | 0.757*** | 0.109 | 6.933 | 0.003 |

| InGE | 0.089*** | 0.039 | 12.284 | 0.000 |

| InRQ | 0.025*** | 0.020 | 8.293 | 0.001 |

| InTI | −0.502*** | 0.011 | −9.060 | 0.000 |

| InGSRD | −0.151*** | 0.038 | −7.641 | 0.001 |

| R-squared | 0.931 | |||

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.930 | |||

| SE of regression | 0.877 | |||

| Long-run variance | 0.936 | |||

| F-statistic | 110.875 | |||

| Prob (F-statistic) | 0.000*** | |||

| DOLS estimates | ||||

| InEGC | −0.619*** | 0.124 | −9.796 | 0.000 |

| InENC | 0.794*** | 0.109 | 7.283 | 0.000 |

| InGE | 0.063*** | 0.040 | 8.052 | 0.001 |

| InRQ | 0.022*** | 0.021 | 10.338 | 0.000 |

| InTI | −0.394*** | 0.011 | −9.840 | 0.002 |

| InGSRD | −0.128*** | 0.037 | −3.343 | 0.011 |

| R-squared | 0.824 | |||

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.878 | |||

| SE of regression | 0.856 | |||

| Long-run variance | 8.256 | |||

| F-statistic | 73.519 | |||

| Prob (F-statistic) | 0.000*** | |||

Note: *** indicates a 1% significance level. EVD-Environmental degradation- EGC-Economic Growth, ENC-energy consumption, RQ-Regulatory quality), GE-Government effectiveness, and GSRD-Government spending on research and development.

As proposed in this research, the results of CS-ARDL proved that economic growth has an inverse and significant connection with EVD in the CEMAC states. The implication is that ecological stability in this region is being affected significantly due to economic growth. Surprisingly, this study outcome shows that a 1% upsurge in EGC neutralizes EVD by 0.572% in the long-term and 0.690% in the short-run. This outcome supports the STIRPAT and EKC assumption that when an economy expands, EVD rises. Nevertheless, with advancements in urbanization and modernization, ecological sustainability increases [52,105,106]. This outcome is consistent with previous studies that asserted that economic growth promotes ecological stability [2,43,48,106]. The results have consequences for the decision-makers who must ensure continued economic growth, which will likely lessen environmental pollution by implementing various safety and quality control measures.

As projected in this study, the influence of ENC on EVD in the CEMAC economies is positive and significant in the long term. Thus, the outcome indicates that a 1% rise in ENU will cause an increase in EVD by 0.754% in the long run and 0.436% in the short-term. These results can be attributed to the assumption that most CEMAC nations rely on non-renewable energy sources, including oil, fossil, and natural gas, for economic expansion. Supporting existing studies [48,77,107,108] established in their papers that ENC in the form of non-renewable sources causes a major threat to ecological sustainability and accounts for an increase in EVD.

Analyzing how GE influences environmental deterioration in the CEMAC economies is equally important. The empirical results of the current study indicate that GE has a significant and positive impact on EVD in CEMAC countries. Hence, the outcome proved that a 1% rise in ineffective governance would cause an increase in EVD by 0.327% in the long term and 0.830%in the short-term. These results can be attributed to the fact that various government attitudes toward implementing and formulating proper initiatives and policies are ineffective in mitigating EVD. Again, transparency issues might also influence why GE contributes to EVD. Thus, transparency may be described as how rules and regulations are obeyed such that there is availability and direct accessibility of information. Moreover, we believe that environmental law is not adequately imposed by the government on firms to follow, which has led to a massive EVD in the CEMAC countries. Our research results contradict those [70,109]. However, our study supports this [2,69].

Moreover, the empirical findings illustrated that RQ positively correlates with EVD in the CEMAC regions. Therefore, based on the results presented in Table 7, a 1% expansion in RQ will eventually lead to an increase in EVD by 0.215% in the long term and 0.270% in the short-term. We can infer from these results that the CEMAC economies have weak institutional strategies for maintaining the environment. These findings further demonstrate the inadequacy of focusing on institutions by themselves to stop environmental deterioration. There is a need for other agents, such as individuals, households, enterprises, and stakeholders, to play an essential role in dissipating environmental EVD. For example, households can enhance clean energy in domestic activities, while enterprises can adopt modern environmental technology to utilize machinery in production. The research supports these existing studies that demonstrated a positive impact of RQ on EVD [110,111]. The study's outcome is inconsistent with those [23].

Congruent with previous studies [61,62,112], this research outcome further underlined that TI has an inverse interplay with EVD. Thus, the findings confirmed that a 1% rise in TI would mitigate EVD by 0.184% in the long term and 0.504% in the short-term. This outcome demonstrates to experience a continuous decline in EVD; the CEMAC countries may use modern technology to control EVD in these regions. Therefore, this study concludes that TI advancement supports the CEMAC economies agenda to achieve ecological stability as suggested by the STIRPAT model [17,87]. In addition [112], indicated that TI might help African countries switch from non-renewable energy sources to cleaner energy, lessening the dependence on natural gas. The usage of renewable energy, encouraged by TI, is therefore expected to lower estimates of the EVD in the CEMAC countries.

The empirical evidence is presented in Table 7, which demonstrates a negative and significant association between GSRD and EVD. If all other variables remain constant, a 1% influence on GRSRD activities decreases EVD by 0.452% in the long run and 0.721% in the short-run. Increased GSRD investment thus obviously implies reduced EVD in the CEMAC state. The scale effect of these analyses demonstrates that government support for research and development improves environmental sustainability. The results of our investigation agree with those of these studies, which reported a negative connection between GSRD and EVD [[24], [25], [26]]. However, our research is disputed by extant literature that argues that GSRD deteriorates the environmental quality and that EVD does not depend on the investment of GSRD [113,114]. The statistical value of of 0.98 demonstrates that the independent parameters have explained the shocks and variations in the explanatory variable of 98%. Moreover, Table 8 provides the robustness results from the FMOL, and DOLS approaches. The findings from the two approaches confirm the outcome of the CS-ARDL. Thus, the FMOLS and DOLS outcomes revealed that EGC, TI, and GSRD have an inverse association with EVD, while ENC, GE, and RQ contribute to a high level of EVD in the CEMAC regions.

4.6. Causality analysis

The Dumitrescu-Hurlin panel data causality test is presented in Table 9. This test provides policy directions to stakeholders and the government in promoting environmental sustainability. The D-H causality assessment outcome shows a unidirectional relationship between ENC, RQ, GE, and EVD. The implication is that every change in the economy's efficiency, government efficiency, energy regulation, and regulatory standards directly affects EVD in the CEMAC states. The outcome is in line with [47,115,116]. However, the causality assessment also showed a bi-directional relationship between EGC, TI, GSRD, and EVD. Programs and policies connected to these factors are determinants of dissipating EVD and promoting ecological sustainability in the CEMAC regions. These results concur with those [32,115,117].

Table 9.

D-H causality test outcome.

| Null Hypothesis | Prob | Decision | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| InEGC ⇎ InEVD | 6.217*** | 3.775 | 0.000 | EGC ⟷ EVD |

| InEVD ⇎ InEGC | 3.637*** | 1.361 | 0.000 | |

| InENC ⇎ InEVD | 3.983*** | 1.676 | 0.000 | ENC → EVD |

| InEVD ⇎ InENC | 1.083 | 0.094 | 0.924 | |

| InGE ⇎ InEVD | 15.603*** | 12.556 | 0.000 | GE → EVD |

| InEVD ⇎ InGE | 1.197 | −0.921 | 0.356 | |

| InRQ ⇎ InEVD | 7.640*** | 5.106 | 0.000 | RQ → EVD |

| InEVD ⇎ InRQ | 0.872 | −1.224 | 0.220 | |

| InTI ⇎ InEVD | 6.472*** | 4.248 | 0.000 | TI ⟷ EVD |

| InEVD ⇎ InTI | 4.173*** | 2.422 | 0.000 | |

| InGSRD ⇎ InEVD | 5.809*** | 3.393 | 0.000 | GSRD ⟷EVD |

Note: *** indicates 1% and 5% significance level, respectively, ⇎ does not granger cause, ⟷ bi-directional and → unidirectional.

5. Conclusion and policy directions

This research investigated the effect of EGC, ENC, GE, TI, RQ, and GSRD on EVD of the CEMAC emerging economies within the EKC and STIRPAT theory by evaluating panel data from 1990 to 2020. To ascertain the long-term estimates, we explore the CSD, heterogeneity, unit root test (CADF and CIPS), and cointegration test among the variables. The modern econometric technique, thus CS-ARDL, was applied to estimate the long-term elasticity coefficient between the regressors and the dependent variable. The study's findings highlighted that economic growth, technological innovation, and government spending on research and development help eradicate environmental degradation in the CEMAC regions. However, the study's empirical outcome proved that energy consumption, government effectiveness, and regulatory quality are detrimental to ecological well-being in these economies. The causality analysis indicated a one-way causality flowing from ENC, RQ, and GE to EVD. Moreover, EGC, TI, and GSRD have a bidirectional connection with EVD. Moreover, theoretically, this study supports the STIRPAT and EKC theory in CEMAC countries. Thus, the analysis revealed that environmental degradation could be dissipated through economic growth, technological innovation, and government spending on research and development.

5.1. Policy directions

In light of the above research findings, this research makes the following policy recommendations to the government and policymakers tasked with ensuring environmental sustainability in these economies.

First, given that the study findings demonstrated that EGC has an inverse connection with EVD, the study proposes that the CEMAC states must continue to establish appropriate initiatives and policies that would be utilized to simultaneously develop their economies and preserve the environment at the same time. Hence, for these countries to achieve ecological stability, this research suggests adopting a greening policy for their economic expansion and working on sustainably modifying their current production and consumption habits. Second, since ENC was empirically established to humiliate environmental sustainability, this study suggests that the CEMAC countries diversify their energy production and usage to cleaner energy to overturn the downward trajectory of the inverse association of ENC with environmental quality.

Third, our study results demonstrated that GE causes environmental deterioration and havoc in the CEMAC economies. Therefore, this research suggests that various governments develop appropriate regulations to avoid any negative externalities leading to higher emissions and address public concerns about environmental deterioration. Government should pay critical attention to the plea of the civil group or political pressures in formulating and implementing quality plans and policies toward protecting the environment. Fourth, given the positive effect of regulatory quality on EVD, more environmental laws and regulations are required in the CEMAC economies to combat climate change. Furthermore, since RQ causes an increase in environmental pollution management, the CEMAC economies must tighten their ecological laws to reduce EVD progressively.

Fifth, the results from this analysis espoused that TI contributes enormously to the mitigation of EVD. Hence, the study outlines that stakeholders and policymakers should prioritize improving environmental-related technologies, allowing these economies to slow the rate of EVD. Moreover, industries and manufacturing firms should be encouraged to adopt environmentally friendly equipment for their production process. Last but not least, it was discovered that GSRD had an inverse impact on environmental degradation in the CEMAC nations. Therefore, we advise governments to keep funding research and development because it helps slow EVD. In addition, this outcome indicates that EVD and air quality are impacted by GSRD changes both instantly and over time. While promoting environmental innovation, governments can do so without limiting the expansion of the manufacturing industry.

5.2. Limitations and future directions

There is a certain limitation to this analysis. First, the current study findings were derived from an econometric evaluation of a few variables over a brief period (i.e., 1990–2020). Future research may examine parameters such as globalization, urbanization, the rule of law, etc., which affect EVD from different jurisdictions using the most recent dataset. Additionally, the analysis can be expanded to developing nations using other econometric approaches to examine the relationships between the variables that impact EVD. Researchers can use updated time series to explore the economic dynamics of alternative energy sources while accounting for structural discrepancies in the data. Finally, endogeneity constraints in the datasets can be rectified, and the current model can be elaborated upon using dynamic panel techniques.

Data availability

WID: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators#

OECD: https://data.oecd.org/envpolicy/patents-on-environment-technologies.htm.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Sampene A.K., Li C., Oteng-Agyeman F., Brenya R. Dissipating environmental pollution in the BRICS economies: do urbanization, globalization, energy innovation, and financial development matter? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-21508-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ngong C.A., Bih D., Onyejiaku C., Onwumere J.U.J. Urbanization and carbon dioxide (CO2) emission nexus in the CEMAC countries. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2022 doi: 10.1108/meq-04-2021-0070. ahead-of-p, no. ahead-of-print. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Djoumessi Djoukouo A.F. Relationship between methane emissions and economic growth in Central Africa countries: evidence from panel data. Glob. Transitions. 2021;3(2021):126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.glt.2022.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Climate Watch . 2022. Equatorial Guinea Climate Change Data | Emissions and Policies | Climate Watch.https://www.climatewatchdata.org/countries/GNQ?end_year=2019&start_year=1990 (accessed Nov. 10, 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sah M.R. Effects of institutional quality on environmental protection in CEMAC countries. Mod. Econ. 2021;12(5):903–918. doi: 10.4236/me.2021.125045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sinha A., Balsalobre-Lorente D., Zafar M.W., Saleem M.M. Analyzing global inequality in access to energy: developing policy framework by inequality decomposition. J. Environ. Manag. Feb. 2022;304:114299. doi: 10.1016/J.JENVMAN.2021.114299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ojekemi O.S., Rjoub H., Awosusi A.A., Agyekum E.B. Do innovation and globalization matter ? Toward a sustainable environment and economic growth in BRICS economies : do innovation and globalization matter. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022;(March) doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-19742-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li X., Ullah S. Caring for the environment: how CO2 emissions respond to human capital in BRICS economies? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022;29(12):18036–18046. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-17025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li C., Sampene A.K., Agyeman F.O., Brenya R., Wiredu J. The role of green finance and energy innovation in neutralizing environmental pollution: empirical evidence from the MINT economies. J. Environ. Manag. 2022;317 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wan Alwi S.R., Klemeš J.J., Varbanov P.S. Cleaner energy planning, management, and technologies: perspectives of supply-demand side and end-of-pipe management. J. Clean. Prod. 2016;136:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.07.181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahmood H., Tawfik T., Alkhateeb Y., Furqan M. Exports, imports, foreign direct investment and CO2 emissions in north Africa : spatial analysis. Energy Rep. 2020;6:2403–2409. doi: 10.1016/j.egyr.2020.08.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pea-Assounga J.B.B., Wu M. Impact of financial development and renewable energy consumption on environmental sustainability: a spatial analysis in CEMAC countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-19972-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bekun F.V., Alola A.A., Sarkodie S.A. Toward a sustainable environment: nexus between CO2 emissions, resource rent, renewable and non-renewable energy in 16-EU countries. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;657:1023–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.12.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sahoo M., Sethi N. The intermittent effects of renewable energy on ecological footprint: evidence from developing countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021;28(40):56401–56417. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-14600-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Usman M., Makhdum M.S.A. What abates ecological footprint in BRICS-T region? Exploring the influence of renewable energy, non-renewable energy, agriculture, forest area, and financial development. Renew. Energy. 2021;179:12–28. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2021.07.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ella P.N., Mabiala J.F., Ikinda L.B.O. Testing the environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis in CEMAC countries. Asian J. Empir. Res. 2022;12(2):82–88. doi: 10.55493/5004.v12i2.4518. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Usman M., Hammar N. Dynamic relationship between technological innovations, financial development, renewable energy, and ecological footprint : fresh insights based on the STIRPAT model for Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021:15519–15536. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-11640-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suki N.M., Suki N.M., Sharif A., Afshan S., Jermsittiparsert K. The role of technology innovation and renewable energy in reducing environmental degradation in Malaysia: a step towards sustainable environment. Renew. Energy. 2022;182:245–253. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2021.10.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li C., Kwasi A., Oteng F., Brenya R., Wiredu J. The role of green finance and energy innovation in neutralizing environmental pollution : empirical evidence from the MINT economies. J. Environ. Manag. 2022;317(June) doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ibrahim R.L., Ajide K.B. The dynamic heterogeneous impacts of non-renewable energy, trade openness, total natural resource rents, financial development and regulatory quality on environmental quality: evidence from BRICS economies. Resour. Pol. 2021;74(July) doi: 10.1016/j.resourpol.2021.102251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halkos G.E., Tzeremes N.G. Carbon dioxide emissions and governance: a nonparametric analysis for the G-20. Energy Econ. 2013;40:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2013.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahmood H., Tanveer M., Omerović E., Furqan M. Rule of law, corruption control, governance, and economic growth in managing renewable and non-renewable energy consumption in south Asia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2021;18(20) doi: 10.3390/ijerph182010637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agyeman F.O., Zhiqiang M., Li M., Sampene A.K. Probing the effect of governance of tourism development, economic growth, and foreign direct investment on carbon dioxide emissions in Africa : the african experience. Energies. 2022:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petrovic P. 2019. The Impact of R & D Expenditures on CO 2 Emissions : Evidence from Sixteen OECD Countries. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez R., Galinato G.I., Islam A. Fiscal spending and the environment: theory and empirics. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2011;62(2):180–198. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Churchill S.A., Inekwe J., Smyth R., Zhang X. R&D intensity and carbon emissions in the G7: 1870–2014. Energy Econ. 2019;80:30–37. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alvarado R., Ortiz C., Jimenez N., Ochoa-Jimenez D., Tillaguango B. Ecological footprint, air quality, and research and development: the role of agriculture and international trade. J. Clean. Prod. 2021;288 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125589. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dumitrescu E.-I., Hurlin C. Testing for Granger non-causality in heterogeneous panels. Econ. Modell. 2012;29(4):1450–1460. [Google Scholar]

- 29.G Gm, K Ab Economic growth and the environment. Q. J. Econ. 1995;110(2):353–377. https://academic.oup.com/qje/article-abstract/110/2/353/1826336 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahmood H. Nuclear energy transition and CO2 emissions nexus in 28 nuclear electricity-producing countries with different income levels. PeerJ. 2022;10 doi: 10.7717/peerj.13780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murshed M., Rahman M.A., Alam M.S., Ahmad P., Dagar V. The nexus between environmental regulations, economic growth, and environmental sustainability: linking environmental patents to ecological footprint reduction in South Asia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021;28(36):49967–49988. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-13381-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Batool Z., Raza S.M.F., Ali S., Abidin S.Z.U. ICT, renewable energy, financial development, and CO2 emissions in developing countries of East and South Asia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2009:2022. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-18664-7. Radhi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mensah R.O., Acquah A., Frimpong A., Babah P.A. Towards improving the quality of basic education in Ghana. Teacher licensure and matters arising: challenges and the way forward. J. Educ. Soc. Policy. 2020;7 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu-Ke C., Hassan M.S., Kalim R., Mahmood H., Arshed N., Salman M. Testing asymmetric influence of clean and unclean energy for targeting environmental quality in environmentally poor economies. Renew. Energy. Sep. 2022;197:765–775. doi: 10.1016/J.RENENE.2022.07.155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Batmunkh A., Nugroho A.D., Fekete-Farkas M., Lakner Z. Global challenges and responses: agriculture, economic globalization, and environmental sustainability in central Asia. Sustain. Times. 2022;14(4) doi: 10.3390/su14042455. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Danish R. Ulucak, Khan S.U.D. Determinants of the ecological footprint: role of renewable energy, natural resources, and urbanization. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020;54(November 2019) doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2019.101996. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hussain M.N., Li Z., Sattar A. Effects of urbanization and non-renewable energy on carbon emission in Africa. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022;29(17):25078–25092. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-17738-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahmood H. The effects of natural gas and oil consumption on CO2 emissions in GCC countries: asymmetry analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022;29(38):57980–57996. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-19851-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balsalobre-Lorente D., Gokmenoglu K.K., Taspinar N., Cantos-Cantos J.M. An approach to the pollution haven and pollution halo hypotheses in MINT countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019;26(22):23010–23026. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-05446-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tauseef S., Awais M., Mahmood N., Zhang J. Linking economic growth and ecological footprint through human capital and biocapacity. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019;47(March) doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2019.101516. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ahmad M., Jiang P., Majeed A., Umar M., Khan Z., Muhammad S. The dynamic impact of natural resources, technological innovations and economic growth on ecological footprint : an advanced panel data estimation. Resour. Pol. 2020;69(July) doi: 10.1016/j.resourpol.2020.101817. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kongbuamai N., Bui Q., Yousaf H.M.A.U., Liu Y. The impact of tourism and natural resources on the ecological footprint: a case study of ASEAN countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020;27(16):19251–19264. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-08582-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Agbede E.A., Bani Y., Azman-Saini W.N.W., Naseem N.A.M. The impact of energy consumption on environmental quality: empirical evidence from the MINT countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021;28(38):54117–54136. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-14407-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nathaniel S.P., Alam M.S., Murshed M., Mahmood H., Ahmad P. The roles of nuclear energy, renewable energy, and economic growth in the abatement of carbon dioxide emissions in the G7 countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021;28(35):47957–47972. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-13728-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Özpolat A. How does internet use affect ecological footprint?: an empirical analysis for G7 countries. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10668-021-01967-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pata U.K. Linking renewable energy, globalization, agriculture, CO2 emissions and ecological footprint in BRIC countries: a sustainability perspective. Renew. Energy. 2021;173:197–208. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2021.03.125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Akinsola G.D., Awosusi A.A., Kirikkaleli D., Umarbeyli S., Adeshola I., Adebayo T.S. Ecological footprint, public-private partnership investment in energy, and financial development in Brazil: a gradual shift causality approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022;29(7):10077–10090. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-15791-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Caglar A.E., Yavuz E., Mert M., Kilic E. The ecological footprint facing asymmetric natural resources challenges: evidence from the USA. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022;29(7):10521–10534. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-16406-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu L., Wang X., Wang L., Zhang D. Does technological advancement impede ecological footprint level ? The role of natural resources prices volatility, foreign direct investment and renewable energy in China. Resour. Pol. 2021;76(December):2022. doi: 10.1016/j.resourpol.2022.102559. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Udeagha M.C., Ngepah N. Does trade openness mitigate the environmental degradation in South Africa? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022;29(13):19352–19377. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-17193-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mehmood U. Environmental degradation and financial development: do institutional quality and human capital make a difference in G11 nations? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022;29(25):38017–38025. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-18825-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.York R., Rosa E.A., Dietz T. STIRPAT, IPAT, and ImPACT: analytic tools for unpacking the driving forces of environmental impacts. Ecol. Econ. 2003;46(3):351–365. [Google Scholar]

- 53.He K., Ramzan M., Awosusi A.A., Ahmed Z., Ahmad M., Altuntaş M. Does globalization moderate the effect of economic complexity on CO2 emissions? Evidence from the top 10 energy transition economies. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/FENVS.2021.778088/PDF. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gyamfi B.A., Onifade S.T., Nwani C., Bekun F.V. Accounting for the combined impacts of natural resources rent, income level, and energy consumption on environmental quality of G7 economies: a panel quantile regression approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022;29(2):2806–2818. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-15756-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mahmood H., Furqan M. Oil rents and greenhouse gas emissions: spatial analysis of Gulf Cooperation Council countries. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021;23(4):6215–6233. doi: 10.1007/s10668-020-00869-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mohanty S., Sethi N. The energy consumption-environmental quality nexus in BRICS countries: the role of outward foreign direct investment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-17180-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mahmood H. 2020. CO2 Emissions, Financial Development, Trade, and Income in North America : A Spatial Panel Data Approach. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rafique M.Z., Nadeem A.M., Xia W., Ikram M., Shoaib H.M., Shahzad U. Does economic complexity matter for environmental sustainability? Using ecological footprint as an indicator. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022;24(4):4623–4640. doi: 10.1007/s10668-021-01625-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fu L., et al. Environmental awareness and pro-environmental behavior within China's road freight transportation industry: moderating role of perceived policy effectiveness. J. Clean. Prod. 2020;252 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119796. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sampene A.K., Li C., Khan A., Agyeman F.O., Brenya R., Wiredu J. The dynamic nexus between biocapacity, renewable energy, green finance, and ecological footprint: evidence from South Asian economies. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s13762-022-04471-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chishti M.Z., Sinha A. Do the shocks in technological and financial innovation influence the environmental quality? Evidence from BRICS economies. Technol. Soc. 2022;68(November 2021) doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101828. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tobelmann D., Wendler T. The impact of environmental innovation on carbon dioxide emissions. undefined. Jan. 2020;244 doi: 10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2019.118787. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Udeagha M.C., Ngepah N. Does trade openness mitigate the environmental degradation in South Africa? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022;29:19352–19377. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-17193-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shahbaz M., Lahiani A., Abosedra S., Hammoudeh S. The role of globalization in energy consumption: a quantile cointegrating regression approach. Energy Econ. 2018;71:161–170. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2018.02.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dasgupta S., Laplante B., Wang H., Wheeler D. Confronting the environmental Kuznets curve. J. Econ. Perspect. 2002;16(1):147–168. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ani A.Z.G. The relationship between good governance and carbon dioxide emissions: evidence from developing economies. J. Econ. Dev. 2012;37(1):77–93. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Almeida T.A. das N., Garcia-Sanchez I.-M. Sociopolitical and economic elements to explain the environmental performance of countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. Jan. 2017;24(3):3006–3026. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-8061-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sarwar S., Alsaggaf M.I. The role of governance indicators to minimize the carbon emission. a study of Saudi Arabia. 2021;32(5):970–988. doi: 10.1108/MEQ-11-2020-0275. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wawrzyniak D., Doryń W. Does the quality of institutions modify the economic growth-carbon dioxide emissions nexus ? Evidence from a group of emerging and developing countries. Econ. Res. Istraživanja. 2020;33(1):124–144. doi: 10.1080/1331677X.2019.1708770. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Abid M. Impact of economic, financial, and institutional factors on CO 2 emissions : evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa economies. Util. Pol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jup.2016.06.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ozturk I., Al-Mulali U., Saboori B. Investigating the environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis: the role of tourism and ecological footprint. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. Jan. 2016;23(2):1916–1928. doi: 10.1007/s11356-015-5447-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fernandez Y.F., Lopez M.A.F., Blanco B.O. Innovation for sustainability: the impact of R&D spending on CO2 emissions. J. Clean. Prod. 2018;172:3459–3467. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kahouli B. The causality link between energy electricity consumption, CO2 emissions, R&D stocks and economic growth in Mediterranean countries (MCs) Energy. 2018;145:388–399. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kocak E., Ulucak Z.S. The effect of energy R&D expenditures on CO 2 emission reduction: estimation of the STIRPAT model for OECD countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019;1 doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-04712-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sampene A.K., Brenya R., Oteng F., Wiredu J. Poverty alleviation in South Africa : the role of agriculture education and mechanization. Asian Journal of Advances in Research. 2022;14(2):4–17. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Adebayo T.S., Odugbesan J.A. 2021. Modeling CO 2 Emissions in South Africa : Empirical Evidence from ARDL Based Bounds and Wavelet Coherence Techniques; pp. 9377–9389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dogan B., Chu L.K., Ghosh S., Diep Truong H.H., Balsalobre-Lorente D. How environmental taxes and carbon emissions are related in the G7 economies? Renew. Energy. Mar. 2022;187:645–656. doi: 10.1016/J.RENENE.2022.01.077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Balsalobre-lorente D., Shahbaz M., Jose C., Jabbour C., Driha O.M. 2019. The Role of Energy Innovation and Corruption in Carbon Emissions : Evidence Based on the EKC Hypothesis. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zakari A., Khan I. The introduction of green finance : a curse or a benefit to environmental sustainability ? Energy Research Letters. 2022;3(2021):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mahmood H. Consumption and territory based CO2 emissions, renewable energy consumption, exports and imports nexus in south America: spatial analyses. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2022;31(2):1183–1191. doi: 10.15244/pjoes/141298. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Raghutla C. 2020. Financial Development, Energy Consumption, Technology, Urbanization, Economic Output and Carbon Emissions Nexus in BRICS Countries : an Empirical Analysis. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rehman S.U., Kraus S., Shah S.A., Khanin D., Mahto R.V. Analyzing the relationship between green innovation and environmental performance in large manufacturing firms. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 2021;163 doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120481. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bakhsh S., Yin H., Shabir M. Foreign investment and CO2 emissions: do technological innovation and institutional quality matter? Evidence from system GMM approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. Apr. 2021;28(15):19424–19438. doi: 10.1007/S11356-020-12237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.WDI . DataBank; 2022. World development indicators.https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators# (accessed Jan. 13, 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 85.OECD . OECD; 2022. Environmental policy - patents on environment technologies.https://data.oecd.org/envpolicy/patents-on-environment-technologies.htm (accessed Jan. 13, 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 86.WGI . Worldwide Governance Indicators; 2022. WGI 2021 interactive > home.https://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/ (accessed Feb. 02, 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang H. Technology innovation, economic growth and carbon emissions in the context of carbon neutrality: evidence from BRICS. Sustain. Times. 2021;13(20) doi: 10.3390/su132011138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pesaran M.H., Schuermann T., Weiner S.M. Modeling regional interdependencies using a global error-correcting macroeconometric model. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 2004;22(2):129–162. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Xue J., Rasool Z., Nazar R., Khan A.I., Bhatti S.H., Ali S. Revisiting natural resources-globalization-environmental quality nexus: fresh insights from South Asian countries. Sustain. Times. 2021;13(8):1–19. doi: 10.3390/su13084224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Baydoun H., Aga M. The effect of energy consumption and economic growth on environmental sustainability in the GCC countries: does financial development matter? Energies. 2021;14(18) doi: 10.3390/en14185897. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Breitung J., Das S. Panel unit root tests under cross‐sectional dependence. Stat. Neerl. 2005;59(4):414–433. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pesaran M.H., Yamagata T. Testing slope homogeneity in large panels. J. Econom. 2008;142(1):50–93. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sun D., Kyere F., Sampene A.K., Asante D., Kumah N.Y.G. An investigation on the role of electric vehicles in alleviating environmental pollution: evidence from five leading economies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-23386-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Maddala G.S., Wu S. A comparative study of unit root tests with panel data and a new simple test. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 1999;61(S1):631–652. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kao C. Spurious regression and residual-based tests for cointegration in panel data. J. Econom. 1999;90(1):1–44. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Westerlund J. Testing for error correction in panel data. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 2007;69(6):709–748. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bhutta A.I., Ullah M.R., Sultan J., Riaz A., Sheikh M.F. Impact of green energy production, green innovation, financial development on environment quality: a role of country governance in Pakistan. Int. J. Energy Econ. Pol. 2022;12(1):316–326. doi: 10.32479/ijeep.11986. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mehmood U., Agyekum E.B., Uhunamure S.E., Shale K., Mariam A. Evaluating the influences of natural resources and ageing people on CO2 emissions in G-11 nations: application of CS-ARDL approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2022;19(3) doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pesaran M.H. Estimation and inference in large heterogeneous panels with a multifactor error structure. Econometrica. 2006;74(4):967–1012. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0262.2006.00692.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Balsalobre-Lorente D., Driha O.M., Bekun F.V., Osundina O.A. Do agricultural activities induce carbon emissions? The BRICS experience. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019;26(24):25218–25234. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-05737-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Muhammad Awais Baloch Y.Q., Danish, Qiu Y. Does energy innovation play a role in achieving sustainable development goals in BRICS countries? Environ. Technol. 2021:1–10. doi: 10.1080/09593330.2021.1874542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kao C., Chiang M.-H. Non-stationary Panels, Panel Cointegration, and Dynamic Panels. Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2001. On the estimation and inference of a cointegrated regression in panel data. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nathaniel S.P., Nwulu N., Bekun F. Natural resource, globalization, urbanization, human capital, and environmental degradation in Latin American and Caribbean countries. Environ. Sci. Pol. 2021;28:6207–6221. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-10850-9/Published. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cai L., Sampene A.K., Khan A., Agyeman F.O., John W., Brenya R. The dynamic nexus between biocapacity, renewable energy, green finance, and ecological footprint: evidence from South Asian economies. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s13762-022-04471-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Grossman G.M., Krueger A.B. Economic growth and the environment. Q. J. Econ. 1995;110(2):353–377. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mahmood H., Alkhateeb T.T.Y., Furqan M. Oil sector and CO2 emissions in Saudi Arabia: asymmetry analysis. Palgrave Commun. 2020;6(1):1–10. doi: 10.1057/s41599-020-0470-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ozgur O., Yilanci V., Kongkuah M. Nuclear energy consumption and CO2 emissions in India: evidence from Fourier ARDL bounds test approach. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.net.2021.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Dogan E., Taspinar N., Gokmenoglu K.K. Determinants of ecological footprint in MINT countries. Energy Environ. 2019;30(6):1065–1086. doi: 10.1177/0958305X19834279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Danish M.A., Baloch, Wang B. Analyzing the role of governance in CO2 emissions mitigation: the BRICS experience. Struct. Change Econ. Dynam. 2019;51:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.strueco.2019.08.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]