Abstract

In the present study, the absorption and desorption kinetics of hydrogen and the isotherm (P–C-T)) of the LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloy were measured at values of 283 K, 303 K, and 313 K. The morphological states of this sample were examined using characterization techniques, including X-ray diffraction and scanning electron microscopy. The thermodynamic functions for the absorption-desorption of hydrogen by hydrides, such as enthalpy (H) and entropy (S), were calculated from the experimental data or by using a model that exists in the literature and is premised on the adjustment of isotherm curves at various temperatures. This model is based on an integrated form of the Van't Hoff equation and a simultaneous examination of the isotherms. According to the experimental results, the amount of hydrogen absorbed or desorbed by the sample is significantly affected by the partial substitution of the nickel atom by the elements Mn and Co. However, this substitution increased the absorption or de-sorption plateau pressure.

Keywords: Hydrogen storage, Isotherm, Enthalpy (ΔH), Entropy (ΔS), Kinetics, LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloy

1. Introduction

At present, hydrogen is viewed in the literature as a crucial component of a sustainable energy system that can deliver affordable and non-polluting energy in the quest for obtaining renewable energy alternatives. As a result, energy experts recommend hydrogen as a practical substitute fuel for several uses [[1], [2], [3], [4]]. In the same way, these types of renewable energy depend on the time factor and the situation. Therefore, it is very important to improve their storage techniques and also the means of transport. Since, these two factors are very expensive and environmentally friendly [[5], [6], [7]]. Hydrogen is the most abundant element in the environment and has a good energy density (147 MJ/kg). Consequently, it is considered one of the ideal energy carriers and used in various applications [8].

Currently, several countries have launched national strategies and studies to develop hydrogen energy. In parallel, research is focused on solving problems related to production techniques, storage, and transport of hydrogen. Hydrogen storage technology is still the major problem in this cycle. Generally, hydrogen can be stored in gas, liquid, and solid forms. Each storage technique has advantages and disadvantages. Hydrogen storage by metal alloys has several advantages over traditional storage techniques (hydrogen gas or liquid).

Since they have a high storage density and favorable kinetics reaction, metals, and intermetallic alloys are metals that can store hydrogen in a reversible manner at temperatures and pressures close to ambient [[9], [10], [11], [12]]. AB5-type alloys have been the subject of various investigations published in the literature in recent years [[13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21]]. For LaNi5-based alloys, some studies assert that a partial element substitution of either La or Ni by other elements can enhance their hydrogen storage capacity.

Nitin and all [22] performed a novel method developed to estimate the gravimetric density or weight percentage of hydrogen. Zhu al [23]. was studied the hydrogen storage performance of LaNi5-xCox alloys (x = 0, 0.25, 0.50, and 0.75). Smith and Goudy [24]. examined the impact of composition substitution in the LaNi5-xCox–H system (x = 0, 1, 2, and 3) on the thermodynamic and kinetic properties. the results obtained reported that the rate of dehydration is inversely corresponding to the hydride stability. They demonstrate that the volume of the cell increases with the increase in the content of the element Co, which results in a reduction of the equilibrium pressure of absorption/desorption of hydrogen and makes the hydride phase more stable. Asano and associates [[25], [26], [27], [28]] studied the stability of the hydride phase as well as the impact of substitutional Cr, Fe, Al, and M elements on the phenomena of hydrogen atom diffusion in the compound VH. They concluded that the stability of the hydride phase as well as the hydrogen atom diffusion occurring at interstitial sites were significantly affected by the concentration of these components.

LaNi5-type alloys are observed to be the most promising H2 storage materials when compared to other materials because of their large volumetric capacity, pleasant cycling behavior, and reaction kinetics. In this regard, it should be noted that the low thermal conductivity of these alloys presents a major challenge to the requirements for hydrogen storage [20]. Numerous studies have determined the production of alloys by replacing Ni with other elements in the combination of LaNi5 (Fe, Co, Al, Mn, etc.) Simultaneously, alloys based on LaNi5 can improve their overall performance regarding the H2 storage technique by the inclusion of metals or transition elements [21,25], and [26]. Similarly, the hydrogenation or dehydrogenation cycles' stability and storage capacity is balanced by the substitution principle of hydrides. Despite this, elemental substitution continues to be a significant issue in research that requires further attention from academics [[21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28]].

In the present study, a new LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloy is created. In-depth experimental research is also conducted on the hydrogen absorption and desorption capacities of isotherms and kinetics. Considerable focus is placed on the impact of partial Ni substitution with Co and Mn on gaseous hydrogen storage capabilities. Furthermore, an adjustment based on the Van't Hoff equation was used to calculate the enthalpy and hydride entropy values of LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5.

2. Experiment

From the raw material (99.97% purity for La, Ni, Mn, and Co), a sample of 1 g of metal powder was created in a glove box in an argon environment. An extremely fine powder was created by mechanically grinding the alloy. Using an experimental Sievert apparatus, the behavior of the alloy's H2 absorption and desorption processes was investigated. Its schematic is illustrated in Fig. 1. The activation operations of this sample were conducted across multiple cycles of cooling at Tfluid = 298 K and applying a pressure of 15 bars for the absorption state, and heating at Tfluid = 333 K and applying a pressure of 2 mbar for the desorption state of pure H2 gas (99.99%). The experimental readings were examined in a hydrogen pressure range of Pap = 8 bar to Pap = 15 bar after the sample was fully activated. The isotherms (P–C-T) were then measured at temperatures ranging from TFluid = 298 K to TFluid = 333 K.

Fig. 1.

Schematic view of experimental installation [29].

A diffractometer was used to calculate the X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements. This measurement technique determines the phase structure of the sample, the network parameters, and the volume of the phase cell. Similarly, the shape and chemical composition of the alloy can be determined using a scanning electron microscope.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Structural analysis, and morphological behavior

The XRD patterns for the LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloy are presented in Fig. 2. The curve reveals that the alloy has a single-phase structure of the CaCu5-type and a space group of the P6/mmc-type. The lattice parameter values and unit lattice volume values of a sample can be determined by analyzing its X-ray diffraction pattern through the Rietveld refinement method.

Fig. 2.

XRD patterns of the LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloy.

The lattice parameter values can be obtained from the refined atomic positions and the crystal symmetry of the sample. The results show that the mesh parameters have values a = 5.0330 Å and c = 3.9967 Å corresponding to a cell volume V = 87.678 Å3 for the LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloy.

According to the results found by Briki et all [29,30], it is clear that the partial substitution of the element Ni in the compound LaNi5 can increase both the lattice parameters (a and c) and the mesh volume of the alloy. Similarly, the LaNi5 compound has the same structure and same lattice parameters a = 5.019 Å and c = 3.982 Å corresponding to V = 86.913 Å3 [29,30] as the LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloy. Therefore, the addition of the element Cobalt (Co) and manganese (Mn) does not induce the formation of new phases but leads to an increase in the lattice parameters “a” and “c” and consequently the increase in the volume of the crystal lattice. This result is in agreement with the sequence of the atomic radii of the metals: RNi (1.24 Å) < RCo (1.25 Å) < RMn (1.37 Å) which indicates that the cell volume of the alloy would increase when Ni was partially replaced by a metal of greater atomic radius.

The LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloy has a cubic crystal structure, the (hkl) indices of its crystal planes can be determined using the Bragg equation (eq (1)):

| (1) |

where n is an integer, λ is the wavelength of the X-ray radiation used for the diffraction experiment, d is the inter-planar spacing, and θ is the angle of diffraction.

The inter-planar spacing of a crystal plane can be calculated using the following equation (eq (2)):

| (2) |

where a is the lattice parameter and h, k, and l are the Miller indices.

The (hkl) indices for LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloy are presented in Fig. 2.

Scanning electron microscopy was used to investigate the morphology of the material. The SEM images show that the alloy is formed by nanoparticles of different dimensions. Also, these photos show that the powder has irregularly shaped and sized particles as a result of high-intensity grinding (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

SEM images of the LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloy; (on top: scale 100 μm, down: scale 50 μm).

Therefore, the grain sizes of this sample vary from around 50 to 100 μm. In addition, the grain size of an alloy changes due to this scrambling before hydrogenation and also decreases with the number of cycles of hydrogen absorption/desorption and desorption then stabilizes.

3.2. Absorption/desorption behavior of hydrogen by the LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloy

Fig. 4 depicts the LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloy's hydrogen absorption rates at temperatures ranging between TFluid = 283 K and TFluid = 313 K with an applied H2 pressure of 15 bar. These curves show that for high temperatures, the amount of hydrogen absorbed at saturation by the LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloy decreases. The compound LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 is found to reach its maximum capacity faster than the compound LaNi5. This is due to several factors including the crystal structure and electronic properties of the compounds. The crystal structure of LaNi5 represents a lower hydrogen diffusion coefficient, which limits the rate of hydrogen uptake and release. In contrast, the crystal structure of LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 can provide more open sites for hydrogen adsorption, which increases the rate of hydrogen uptake and release. for this, crystal structure, and electronic properties of compounds can also play an important role in their hydrogen storage properties. Adding the elements of Co and Mn to LaNi5 can change the electronic structure of the compound, which can affect the bond energy between hydrogen and metal atoms. This can result in a higher hydrogen uptake and release rate compared to LaNi5. These curves show that substitution on the nickel group can improve the absorption/desorption kinetic properties of hydrogen.

Fig. 4.

Hydrogen absorption characteristics of LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloy (working condition: TFluid = 283 K to TFluid = 313 K and at P0 = 15 bar).

Simultaneously, it can be observed that this behavior, in contrast to the reaction kinetics of the LaNi5 compound's hydrogen absorption capacity, is qualitatively more significant. This is demonstrated by the improvement in the kinetics behavior caused by the partial replacement of the Ni element by the Co and Mn elements. In addition, the cobalt metal presents strong catalytic activity that can aid in the migration of hydrogen atoms inside the alloy's grain boundaries. This justification is supported by the previously con-ducted research that indicates the dissociation of H2 atoms might be aided by the addition of lower-valence metals to transition metals [[30], [31], [32], [33]].

The LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloy's desorption process curve is depicted in Fig. 5 at temperatures ranging from TFluid = 283 K to TFluid = 308 K and at a hydrogen pressure of 2 mbar. It is evident that when the temperature increases, the alloy's hydrogen desorption kinetics considerably accelerate. At an increasing temperature of TFluid = 303 K, the LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloy may release approximately 10−2 g of hydrogen in approximately 20 min; however, at a warming temperature of TFluid = 283 K, the entire dehydrogenation process takes about 40 min.

Fig. 5.

Hydrogen desorption characteristics of LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloy (working condition: TFluid = 283 K, TFluid = 298 K, TFluid = 308 K and at Pap = 2 mbar).

The temperature variation that occurs during the hydrogen absorption/desorption cycle is illustrated in Fig. 6. A temperature probe was used inside the reactor to measure the temperature evolution that occurred during the absorption/desorption process of hydrogen. It can be observed that at the rate of insertion of the hydrogen atoms, the temperature inside the hydride bed increases until a saturation temperature of the order of Tsat = 319.5 K is expected, and then decreases until it reaches the operating temperature.

Fig. 6.

Evolution of the temperature of the LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloy during the absorption and de-sorption processes of hydrogen.

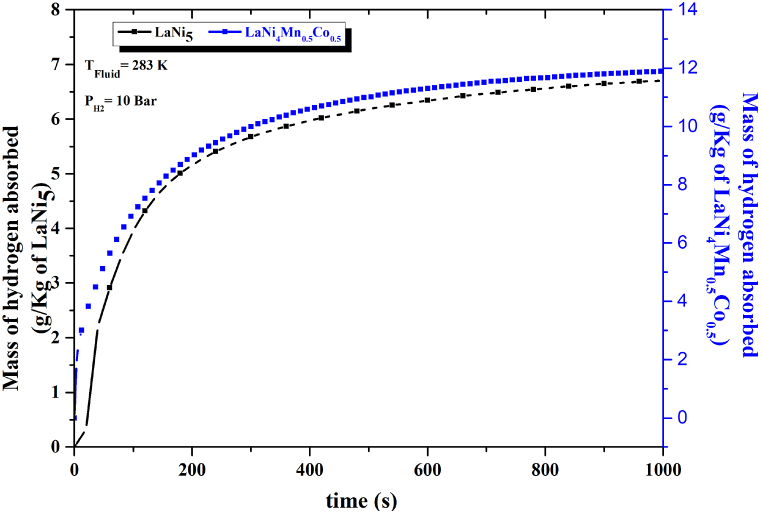

To understand the effect of substitution on the performance of LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloy reactive kinetics, The hydrogen absorption curves for the LaNi5 and LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloys under a temperature T = 283 K and a pressure P = 10 bar are shown in Fig. 7. It can be seen that the LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloy has a very fast kinetics as the LaNi5 alloy.

Fig. 7.

Evolution of the mass of hydrogen absorbed by the alloys LaNi5 and LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 for P = 10 bar and T = 283 K.

The substitution of the nickel atom (Ni) with manganese (Mn) and cobalt (Co) elements in the LaNi5 alloy leads to an improvement in the kinetics of hydrogen absorption Fig. 7. This is explained by changes in network parameters that cause variations in the crystalline structure. These factors influence the speed at which hydrogen atoms diffuse into the LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloy.

Furthermore, the changes occurring in the absorbed or desorbed hydrogen are affected by the increase and decrease in temperature levels (see Fig. 4, Fig. 5). It is clear that the hydride bed rapidly tends towards the maximum hydrogen capacity, causing a decrease in the rate of heat generation, and thus the rapid cooling of the hydride bed.

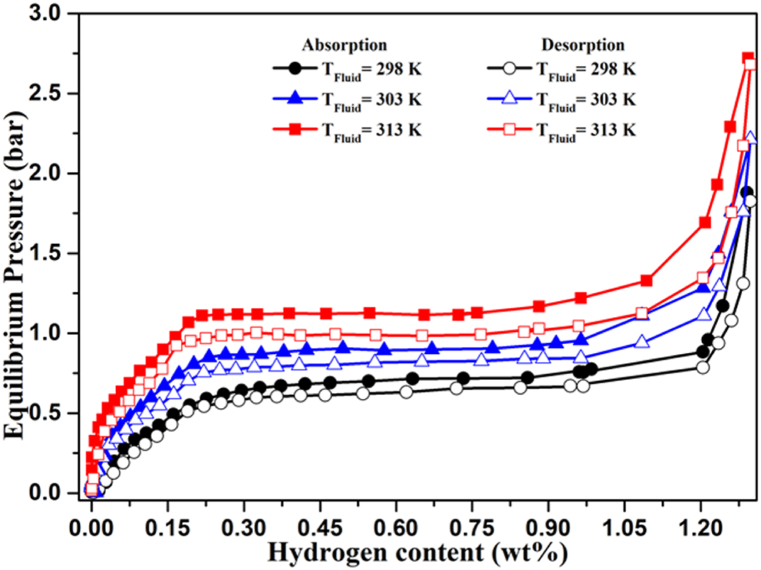

Fig. 8 depicts the pressure-concentration-temperature curves for the LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloy at values of T = 298, T = 303, and T = 313 K. The experimental values are grouped in Table 1 as [H/M]abs and [H/M]des, which demonstrate the greatest capabilities for hydrogen absorption and desorption processes, respectively; Peq is the equilibrium pressure in the center of the plateau zone; and Hys is the hysteresis factor.

Fig. 8.

Pressure-concentration-temperature curves of the LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloy at different temperatures.

Table 1.

Experimental hydrogen storage parameters of the LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloy.

| Temperature (K) | Hydrogen desorbed |

Hydrogen absorbed |

Hf(Jmol−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [H/M]des | Peq(bar) | [H/M]abs | Peq(bar) | ||

| 298 | 0.62 | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.71 | 148 |

| 303 | 0.65 | 0.81 | 0.67 | 0.9 | 132 |

| 313 | 0.64 | 0.98 | 0.66 | 1.11 | 162 |

The mechanism for assessing a metal's resistance to sputtering during hydrogenation/dehydrogenation cycles is the hysteresis phenomenon. The Van 't Hoff equation, which represents the change in pressure at the plateau's midpoint over an absorption/desorption cycle of hydrogen H2, was used to calculate the experimental values of hysteresis.

The outcomes are presented in Table 1. This table exhibits that, despite the increase in the temperature, there is a minor fluctuation occurring in the maximum quantity of hydrogen that our sample could absorb and desorb. On the other hand, it can be observed that when the temperature increases, the plateau pressure also increases. This is explained by how weakly our hydride stabilizes at higher temperatures. Therefore, it is evident that increasing temperatures hinder the phenomena of hydrogen absorption by metallic alloys, while favoring the process of H2 desorption [[33], [34], [35]].

Fig. 9 shows a comparison of the isotherms of the LaNi5 and LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloys. It is remarkable the effect of substitution in LaNi5 of the elements Mn and Co on the equilibrium pressures of the plate also on the amount stored at saturation. Several elements can substitute the elements La or Ni giving changes in the hydrogenation properties. But unfortunately, hydrogen storage capacity can never be increased by these substitutions. It is clear that there is a decrease in the amount of hydrogen absorbed at saturation of the order of 0.1 wt%. But the most important effect of substitution on the storage properties of hydrogen is proved by the pressure of the plate, which is dominated by the half to LaNi5 alloy.

Fig. 9.

The hydrogen absorption isotherms for LaNi5 and LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloys at T = 303 K and T = 313 K.

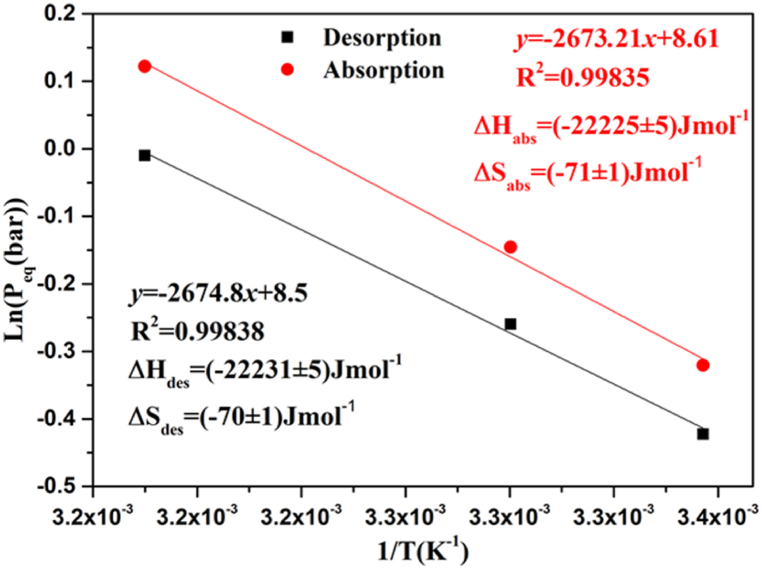

The values of reaction enthalpy “H" and entropy “S" are determined from the equation of Van't Hoff (eq (3)).

| (3) |

where T(K) is the experiment temperature, Peq (bar) is the equilibrium pressure, R = 8.314 Jmol−1K−1 is the universal gas constant, and S (Jmol−1K−1) and H (Jmol−1K−1) are the entropy and enthalpy activities of the process, respectively.

Fig. 10 depicts the development of the plateau pressure (Peq) as a function of the temperature's reciprocity (1/T). These findings demonstrate that the connection between (Peq) and (1/T) on Van't Hoff plots is linear. By adjusting the experimental data with the parameters of this equation, the ΔH and ΔS values for the absorption and desorption processes of H2 by the LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloy are: ΔH = 22225 ± 5 Jmol-1 and ΔS = ±71 ± 1 Jmol-1. The isotherms of the LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloy for different temperatures show a reversible hydrogen sorption capacity of 1.2% by weight and a pressure value of the equilibrium that does not exceed 1 bar. For this reason, the decrease in plateau pressure is mainly related to the stability of the hydride, which has an enthalpy value of 71.1 J/mol and an entropy of 22225 J/mol. It can be noted that the formation enthalpy of the LaNi5 alloy (ΔHLaNi5 = 30.1 KJmol-1 [[36], [37], [38], [39]]) is higher than the value of the H enthalpy of the alloy under study. In this case, it is clear that the partial substitution of the atom of Ni by the elements Mn and Co has a significant effect on the decrease of the plateau and reduces hysteresis.

Fig. 10.

The van't Hoff plot for the LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloy was obtained using the data from Fig. 7.

4. Conclusion

By using X-ray diffraction techniques and scanning electron microscopy, the mi-cro-structural properties and phase compositions of the LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 alloy were inves-tigated in the present study.

Similarly, the LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 hydride's' hydrogen storage capabilities were experi-mentally investigated by obtaining measurements of the reaction kinetics and from the isotherms (P–C-T).

The empirical values of the hydride's enthalpy (H) and entropy (S) values were cal-culated by fitting the experimental data to the isotherms using the Van't Hoff equation.

According to the results, the intermetallic compound LaNi4Mn0·5Co0.5 exhibits im-proved hydrogen absorption/desorption kinetics due to the partial substitution of Ni by Mn and Co elements.

Author contribution statement

Chaker Briki: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Sihem Belkhiria: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Maha Almoneef: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Mohamed Mbarek: Performed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Abdelmajid Jemni: Conceived and designed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2023R56), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

References

- 1.Abas N., Kalair A., Khan N. Review of fossil fuels and future energy technologies. J. Futures. 2015;69:31–49. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canan A., Ibrahim D. 1.13 hydrogen energy. J. Compr. Energy Syst. 2018;1:568–605. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hosseini S.E., Wahid M.A. Hydrogen production from renewable and sustainable energy resources: promising green energy carrier for clean development. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy Reviews. 2016;57:850–866. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sinigaglia T., Lewiski F., Santos Martins M.E., Mairesse Siluk J.C. Production, storage, fuel stations of hydrogen and its utilization in automotive applications-a review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2017;42(39):24597–24611. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bionaz D., Marocco P., Ferrero D., Sundseth K., Santarelli M. Life cycle environmental analysis of a hydrogen-based energy storage system for remote applications. Energy Rep. 2022:5080–5092. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ayodele T.R., Mosetlhe T.C., Yusuff A.A., Ogunjuyigbe A.S.O. Off-grid hybrid renewable energy system with hydrogen storage for South African rural community health clinic. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2021;46(38):19871–19885. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang J., Xu X., Wu L., Chen Z., Hu W. Risk-averse based optimal operational strategy of grid-connected photovoltaic/wind/battery/diesel hybrid energy system in the electricity/hydrogen markets. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2023;48(12):4631–4648. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rasul M.G., Hazrat M.A., Sattar M.A., Jahirul M.I., Shearer M.J. The future of hydrogen: challenges on production, storage and applications. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022;272 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakintuna B., Lamari-Darkrim F., Hirscher M. Metal hydride materials for solid hydrogen storage: a review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2007;32(9):1121–1140. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Percheron-Guégan A., Lartigue C., Achard J.C. Correlations between the structural properties, the stability and the hydrogen content of substituted LaNi5 compounds. J. Less Common Metals. 1985;109(2):287–309. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eliezer D., Eliaz N., Senkov O.N., Froes F.H. Positive effects of hydrogen in metals. J. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 2000;280(1):220–224. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bobet J.L., Akiba E., Nakamura Y., Barriet D. Study of Mg-M (M=Co, Ni and Fe) mixture elaborated by reactive mechanical alloying — hydrogen sorption properties. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2000;25(10):987–996. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang L., Young K., Meng T., Ouchi T., Yasuoka S. Partial substitution of cobalt for nickel in mixed rare earth metal based superlattice hydrogen absorbing alloy-Part 1 structural, hydrogen storage and electrochemical properties. J. Alloys Compd. 2016;660:407–415. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Łodziana Z., Dębski A., Cios G., Budziak A. Ternary LaNi4.75M0.25 hydrogen storage alloys: surface segregation, hydrogen sorption and thermodynamic stability. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2019;44(3):1760–1773. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang F.S., Chen X.Y., Wu Z., Wang S.M., Wang G.X., Zhang Z.X., Wang Y.Q. Experimental studies on the poisoning properties of a low-plateau hydrogen storage alloy LaNi4.3Al0.7 against CO impurities. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2017;42(25):16225–16234. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Mal H.H., Buschow K.H.J., Miedema A.R. Hydrogen absorption in LaNi5 and related compounds: experimental observations and their explanation. J. Less-Common Met. 1974;35:65–76. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borzone E.M., Blanco M.V., Baruj A., Meyer G.O. Stability of LaNi5-xSnx cycled in hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2014;39:8791–8796. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang J.B., Tai C.Y., Marasinghe G.K., Waddill G.D., Pringle O.A., James W.J. Electronic structures and magnetism of LaNi5-xFex compounds. J. Appl. Phys. 2001;89:7311–7313. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang C., Liu Y., Zhao X., Yan M., Gao T. First-principles study of the crystal structures and electronic properties of LaNi4.5M0.5 (M-Al, Mn, Fe, Co) Compd. Mater. Sci. 2013;69:520–526. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang R.J., Wang Y.M., Lu M.Q., Xu D.S., Yang K. First-principles study on the crystal, electronic structure and stability of LaNi5-xAlx (x=0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75 and 1) Acta Mater. 2005;53:3445–3452. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mendelsohn M.H., Gruen D.M. The Effect of group III a and IV a element substitutions (M) on the hydrogen dissociation pressures of LaNi5-xMx hydrides. Rare Earths Mod. Sci. Technol. 1980;2:593–598. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luhadiya N., Kundalwal S.I., Sahu S.K. Investigation of hydrogen adsorption behavior of graphene under varied conditions using a novel energy-centered method. Carbon Lett. 2021;31:655–666. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu Z., Zhu S., Lu H., Wu J., Yan K., Cheng H., Liu J. Stability of LaNi5-xCox alloys cycled in hydrogen — Part 1 evolution in gaseous hydrogen storage performance. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2019;44(29):15159–15172. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith G., Thermodynamics A.J. Goudy. Kinetics and modeling studies of the LaNi5−xCox hydride system. J. Alloys Compd. 2001;316(1–2):93–98. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asano K., Hayashi S., Nakamura Y. Formation of hydride phase and diffusion of hydrogen in the V-H system varied by substitutional Fe. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2016;41(15):6369–6375. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asano K., Hayashi S., Nakamura Y., Akiba E. Effect of substitutional Mo on diffusion and site occupation of hydrogen in the BCT monohydride phase of V-H system studied by 1H NMR. J. Alloys Compd. 2010;507(2):399–404. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Asano K., Hayashi S., Nakamura Y. Enhancement of hydrogen diffusion in the body-centered tetragonal monohydride phase of the V-H system by substitutional Al studied by proton nuclear magnetic resonance. Acta Mater. 2015;83:479–487. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Asano K., Hayashi S., Nakamura Y., Akiba E. Effect of substitutional Cr on hydrogen diffusion and thermal stability for the BCT monohydride phase of the V-H system studied by 1H NMR. J. Alloys Compd. 2012;524:63–68. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Briki C., de Rango P., Belkhiria S., Dhaou M.H., Jemni A. Measurements of expansion of LaNi5 compacted powder during hydrogen absorption/desorption cycles and their influences on the reactor wall. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2019;44(26):13647–13654. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Briki C., Belkhiria S., Dhaou M.H., de Rango P., Jemni A. Experimental study of the influences substitution from Ni by Co, Al and Mn on the hydrogen storage properties of LaNi3.6Mn0.3Al0.4Co0.7 alloy. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2017;42(15):10081–10088. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Briki C., Bouzid M., Dhaou M.H., Jemni A., Lamine A.B. Experimental and theoretical study of hydrogen absorption by LaNi3.6Mn0.3Al0.4Co0.7 alloy using statistical physics modeling. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2018;43(20):9722–9732. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Souza E.C., Ticianelli E.A. Effect of partial substitution of nickel by tin, aluminum, manganese and palladium on the properties of LaNi5-type metal hydride alloys. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2003;14:544–550. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang T., Yuan Z., Bu W., Jia Z., Qi Y., Zhang Y. Effect of elemental substitution on the structure and hydrogen storage properties of LaMgNi4 alloy. J. Mater. Design. 2016;93(5):46–52. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Young K., Ouchi T., Huang B. Effects of various annealing conditions on (Nd, Mg, Zr)(Ni, Al, Co)3.74 metal hydride alloys. J. Power Sour. 2014;248:147–153. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo F., Zhang T., Shi L., Song L. Hydrogen absorption/desorption cycling performance of Mg-based alloys with in-situ formed Mg2Ni and LaHx (x = 2, 3) nanocrystallines. J. Magnesium Alloys. 2023;11(4):1180–1192. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ojeda X.A., Castro F.J., Pighin S.A., Troiani H.E., Moreno M.S. Hydrogen absorption and desorption properties of Mg/MgH2 with nanometric dispersion of small amounts of Nb(V) ethoxide. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2021;46(5):4126–4136. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cardoso K.R., Roche V., Jorge A.M., Zepon G., Champion Y. Hydrogen storage in MgAlTiFeNi high entropy alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2021;858 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin Q., Zhao S., Zhu D.J., Chen N. Structure and properties of the MlNi5 system with tin substitution. Solid State Ionics. 2000;136–137:663–666. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ma X., Wei X., Dong H., Liu Y. The relationship between discharge capacity of LaNi5 type hydrogen storage alloys and formation enthalpy. J. Alloys Compd. 2010;490(1–2):548–551. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.