Abstract

South Asian gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) in the United States are subsumed under the broad, heterogeneous category of Asian GBMSM in national surveillance systems. Disaggregated data on their rates of HIV and sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing are not publicly reported. This is problematic as the diversity of ancestries, cultures, and customs across subgroups of Asian GBMSM may contribute to differential HIV and STI testing experiences. To address this deficit in knowledge, 115 South Asian GBMSM recruited through social media advertising and peer referral were surveyed about their patterns of HIV and STI testing. In the past 6 months, almost two-thirds (n = 72, 62.61%) had two or more male sex partners, and more than a quarter (n = 33, 28.70%) had condomless anal sex with two or more male partners. In the past year, more than one in four (n = 32, 27.83%) had not been tested for HIV, and more than two in five (n = 47, 40.87%) had not been tested for STIs. The prevalence of past-year HIV and STI testing was lower among participants aged ≥35 years and those who had never used pre-exposure prophylaxis. Participants who were partnered were less likely to have been tested for HIV, and those who were born outside the United States were less likely to have been tested for STIs in the past year. Findings highlight gaps in domestic HIV- and STI-prevention efforts with respect to adequately engaging South Asian GBMSM and suggest that some segments of this subgroup may benefit from targeted outreach.

Keywords: HIV, sexually transmitted infections, South Asians, sexual and gender minorities, risk reduction

Introduction

Gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) in the United States remain disproportionately affected by HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) such as gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis (CDC, 2022a, 2022b). Regular testing is important for the timely diagnosis and management of these infections to prevent health complications and reduce the potential for onward transmission. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that all sexually active GBMSM should be tested for HIV, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis at least once a year and more frequently (e.g., every 3–6 months) based on their individual risk factors (DiNenno et al., 2017; Workowski et al., 2021). However, national surveillance data indicate that the actual rates of HIV and STI testing among GBMSM are less than optimal (DiNenno et al., 2022; Hoots et al., 2018). Commonly cited reasons to avoid or delay being tested include perceptions of low risk, concerns around privacy or confidentiality, fear of receiving a positive test result, anticipated or experienced homophobia, and limited geographic or financial access to health care (Heijman et al., 2017; Kobrak et al., 2022; McKenney et al., 2018).

Given the higher burden of HIV and STIs among African American/Black and Hispanic/Latino GBMSM relative to those of other races/ethnicities (CDC, 2022a, 2022b), federal agencies are making concerted attempts to engage these subgroups in state and local prevention programs (HHS, 2022a, 2022b). Researchers are also devoting significant attention to the development, evaluation, and implementation of culturally relevant interventions aimed at reducing sexual risk behaviors and increasing testing (Perez et al., 2018; Ramos et al., 2021; Sutton et al., 2021). One subgroup that has been overlooked in domestic HIV- and STI-prevention efforts is South Asian GBMSM. South Asian Americans trace their ethnic origins to different countries in the Indian subcontinent (e.g., Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka) but share a multitude of social, cultural, and health-related norms (Lucas et al., 2013; Subedi et al., 2022). Between 2010 and 2019, the number of South Asian Americans grew from 3.86 million to 5.65 million, representing an increase of 46% (Budiman & Ruiz, 2021). Indians comprise more than 81% of the total South Asian population in the United States, followed by Pakistanis, Bangladeshis, Nepalis, Sri Lankans, and Bhutanese (Budiman & Ruiz, 2021). Of note, a large proportion of South Asian Americans are immigrants, with 68% of Indians, 65% of Pakistanis, 72% of Bangladeshis, 83% of Nepalis, 80% of Sri Lankans, and 85% of Bhutanese being foreign-born (Budiman & Ruiz, 2021).

South Asian GBMSM in the United States are vulnerable to multiple stressors such as migration, homophobia, and racism, all of which can increase their risk of acquiring HIV and STIs. A recent investigation of HIV nucleotide sequence data from 77,686 persons, including 12,064 (16%) foreign-born persons, provides strong evidence for post-migration HIV acquisition (Valverde et al., 2017). On examining the place of birth of potential HIV transmission partners of foreign-born persons, the study found that 68% of potential HIV transmission partners of Asian immigrants and 81% of potential HIV transmission partners of GBMSM immigrants were born in the United States (Valverde et al., 2017). Although data on the place of birth of potential HIV transmission partners of South Asian GBMSM immigrants specifically were not reported, the study highlights the role of migration as a risk factor for HIV. In addition, research conducted with South Asian GBMSM in Canada (Ghabrial, 2017; Souleymanov et al., 2020) and the United Kingdom (Jaspal, 2017; McKeown et al., 2010) indicates that members of this subgroup often experience homophobia within the larger South Asian community and racism within the larger GBMSM community. Both homophobia and racism have been linked to high rates of sexual risk behaviors among African American/Black and Hispanic/Latino GBMSM in the United States (Amola & Grimmett, 2015; Diaz et al., 2020; Jeffries et al., 2013; Mizuno et al., 2012) and may act similarly among South Asian GBMSM. Qualitative research from Canada also suggests that the discrimination experienced by South Asian GBMSM from those of other races/ethnicities may result in them making compromises to feel sexually desirable, such as being the receptive anal sex partner against their preference and refraining from using condoms with casual sex partners, heightening their susceptibility to HIV and STIs (Hart et al., 2021).

Despite the existence of these risk factors, little is known about the epidemiology of HIV and STIs among South Asian GBMSM in the United States because they are conventionally subsumed under the broad, heterogeneous category of Asian GBMSM in national surveillance systems (CDC, 2020, 2022c). Asian Americans also include persons who link their heritage to countries in East Asia (e.g., China, Japan, Taiwan) and Southeast Asia (e.g., Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand) (Budiman & Ruiz, 2021). Disaggregated data on the rates of HIV and STI testing among South Asian GBMSM are not publicly reported by federal, state, or local public health agencies. Even the limited number of published studies exclusively involving samples of Asian GBMSM recruited from large metropolitan cities such as Boston, Los Angeles, New York City, San Francisco, and Seattle have not presented results from ethnic-stratified analyses (Choi et al., 2005; Do et al., 2005, 2006; Lloyd et al., 1999; Shapiro & Vives, 1999; Wong et al., 2012). This is problematic as the diversity of ancestries, cultures, and customs across subgroups of Asian GBMSM may contribute to differential HIV and STI testing experiences. To address this deficit in knowledge, this article seeks to describe patterns of HIV and STI testing in a national sample of sexually active South Asian GBMSM and report on variations in past-year HIV and STI testing across strata of demographic and behavioral characteristics.

Method

Study Design

Ujala (meaning “light” or “bright” in multiple South Asian languages) was a cross-sectional study conducted from April to July 2022 that aimed to collect pilot data on HIV and STI risk and preventive behaviors among South Asian GBMSM in the United States. Study materials and procedures were reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at the University of Michigan (approval number: HUM00209310). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Participant Recruitment

Recruitment was conducted through contacting administrators of online South Asian LGBTQ+ groups across the United States (e.g., MASALA Boston, Trikone Atlanta, Khush DC, Trikone Bay Area, Khush ATX, Trikone Chicago) and requesting them to post advertisements on their social media channels. Advertisements included the Ujala study logo, images of South Asian men in traditional outfits, and the University of Michigan logo. One example of a recruitment advertisement is depicted in Figure 1. Individuals who clicked on the link to the study’s landing page (programmed in Qualtrics) were presented with a brief overview of the protocol and the informed consent form, a copy of which they could download for their records. CAPTCHA (i.e., Completely Automated Public Turing Test to tell Computers and Humans Apart) was used to prevent automated spam bots from proceeding. Individuals who provided informed consent were directed to a brief eligibility screener. The study’s eligibility criteria included (a) identifying as male, (b) being at least 18 years of age, (c) identifying as South Asian, (d) residing in the United States or dependent areas, (e) having at least one male sex partner in the past 6 months, (f) not known to be living with HIV, and (g) willing to provide a name and email address to receive a US$25 Amazon e-gift card. Individuals who met the study’s eligibility criteria were directed to a survey to collect data on their demographic and behavioral characteristics, along with their patterns of HIV and STI testing. “Honeypot” questions (i.e., questions programmed to only be “visible” to spam bots) were embedded in the survey as an additional protection measure. At the end of the survey, participants were requested to share the link to the study’s landing page with others in their network who they believed might be interested in participating. Individuals who did not provide informed consent or meet the study’s eligibility criteria were thanked for their interest and directed to the CDC’s website containing resources on HIV and STI risk reduction.

Figure 1.

Example of an Advertisement Used to Recruit 115 South Asian GBMSM in the United States, April to July 2022

Note. GBMSM = gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men.

Data Collection

Demographic information obtained from participants included their age, ethnic origin, educational level, employment status, health insurance coverage, sexual orientation, place of birth, and relationship status. Behavioral information included the number of male sex partners in the past 6 months, the number of male partners with whom participants had condomless anal sex (CAS) in the past 6 months, and the use of alcohol or drugs immediately before or during sex in the past 6 months. CAS was defined as “topping” (i.e., having insertive anal sex) or “bottoming” (i.e., having receptive anal sex) with a male partner during which a condom was not used the entire time. Participants were also asked to indicate whether they had ever used pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention, and if so, whether they were using PrEP at the time of the survey.

Patterns of HIV and STI testing were assessed using a series of questions analogous to previous research conducted with GBMSM (Rendina et al., 2014; Sharma et al., 2022; Vincent et al., 2017). Participants were asked to indicate whether they had ever been tested, separately for HIV and STIs (response options: “Yes” or “No”), and if so, when they took their most recent tests (response options: “In the past 3 months,”“3 to 6 months ago,”“6 months to 1 year ago,”“1 to 2 years ago,”“More than 2 years ago”), where they took their most recent tests (response options: “Private doctor’s office,”“Community health center,”“Urgent care center or walk-in clinic,”“Hospital emergency room,”“School or college clinic,”“HIV or STI testing center,”“Mobile testing unit,”“Home or other private location”), and how often they got tested (response options: “Every 3 months,”“Every 6 months,”“Every year,”“Every time I think I might have been exposed,”“I do not test regularly”).

Data Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS. Given this article’s focus on patterns of HIV and STI testing, the analytic sample was restricted to participants who provided complete information on these outcomes. Chi-square tests for homogeneity were performed to compare the demographic and behavioral characteristics of participants who were excluded from the analytic sample with those of participants who were included (except for when the expected cell counts were lower than five, in which case Fisher’s exact tests were performed).

Descriptive statistics were computed to summarize participant characteristics, including ever being tested for HIV and STIs, time and location of one’s most recent tests, and frequency of testing. For analytical purposes, responses to the questions on ever being tested for HIV and time of one’s most recent test were combined to construct a dichotomous variable for past-year HIV testing (i.e., tested versus did not test for HIV), and responses to the questions on ever being tested for STIs and time of one’s most recent test were combined to construct another dichotomous variable for past-year STI testing (i.e., tested versus did not test for STIs). Age (collected as a continuous variable) was dichotomized at the sample mean. Ethnic origin was dichotomized into Indian and other (due to the small numbers of participants who were Pakistani, Nepali, Sri Lankan, Bangladeshi, or Sindhi). Health insurance coverage was dichotomized into having a private health plan and other (due to the small numbers of participants who were insured under Medicare or Medicaid, the Affordable Care Act, the Veterans Affairs health plan, or some other health plan, or were not insured under any health plan). Sexual orientation was dichotomized into gay and other (due to the small numbers of participants who identified as bisexual, pansexual, queer, or questioning). Variations in past-year HIV and STI testing across the strata of demographic and behavioral characteristics were examined using simple log-binomial regression models, and the results are reported as prevalence ratios (PRs) with 95% confidence intervals. PRs were preferred over odds ratios to avoid overestimating the strength of the associations because of the high prevalence of each outcome (Tamhane et al., 2016; Walter, 2000).

Results

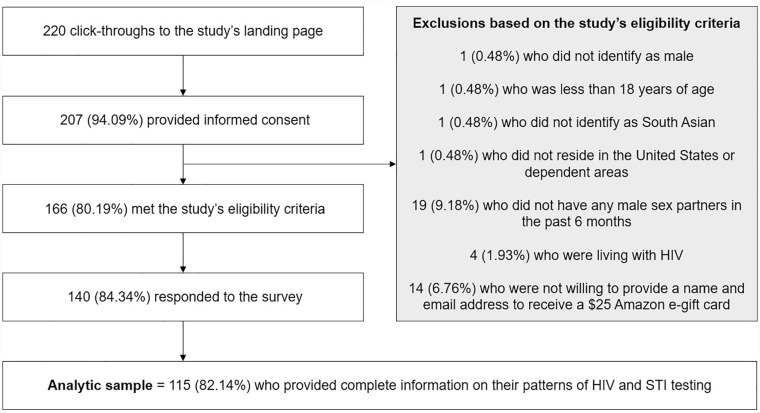

Details pertaining to participant recruitment are presented in Figure 2. Of the 140 individuals who responded to the survey, 115 (82.14%) provided complete information on their patterns of HIV and STI testing and were included in the analytic sample. Of these, 36 (31.30%) reported learning about the study through social media channels and 79 (68.70%) through a friend or a sex partner. Also, 19 (16.52%) resided in the Northeast, 37 (32.17%) resided in the Midwest, 40 (34.78%) resided in the South, and 17 (14.78%) resided in the West of the United States. No significant demographic or behavioral differences were observed between participants who were excluded from the analytic sample and those who were included (analyses not presented).

Figure 2.

Derivation of the Analytic Sample of 115 South Asian GBMSM in the United States, April to July 2022

Note. GBMSM = gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men.

Sample Characteristics

Descriptive characteristics of the 115 participants are summarized in Table 1. Ages ranged from 22 to 57 years, with 51 (44.35%) being ≥35 years. The majority were Indian (n = 103, 89.57%), had a master’s degree or higher educational level (n = 84, 73.04%), were working full time or part time (n = 97, 84.35%), were insured under a private health plan (n = 101, 87.83%), and identified as gay (n = 100, 86.96%). Approximately three-fourths (n = 87, 75.65%) were born outside the United States, and almost half (n = 53, 46.09%) were partnered. Regarding sexual risk behaviors, almost two-thirds (n = 72, 62.61%) had two or more male sex partners, and more than a quarter (n = 33, 28.70%) had CAS with two or more male partners in the past 6 months. Approximately half (n = 57, 49.57%) had previously used or were using PrEP at the time of the survey.

Table 1.

Demographic and Behavioral Characteristics of 115 South Asian GBMSM in the United States, April to July 2022

| Characteristic | n | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age a | ||

| <35 years | 64 | (55.65) |

| ≥35 years | 51 | (44.35) |

| Ethnic origin | ||

| Indian | 103 | (89.57) |

| Other b | 12 | (10.43) |

| Educational level | ||

| Bachelor’s degree or lower | 31 | (26.96) |

| Master’s degree or higher | 84 | (73.04) |

| Employment status | ||

| Working full time or part time | 97 | (84.35) |

| Studying or not employed | 18 | (15.65) |

| Health insurance coverage | ||

| Private health plan | 101 | (87.83) |

| Other c | 14 | (12.17) |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Gay | 100 | (86.96) |

| Other d | 15 | (12.59) |

| Place of birth | ||

| United States | 28 | (24.35) |

| Outside the United States | 87 | (75.65) |

| Relationship status | ||

| Single | 60 | (52.17) |

| Partnered | 53 | (46.09) |

| Number of male sex partners in the past 6 months | ||

| 1 | 43 | (37.39) |

| ≥2 | 72 | (62.61) |

| CAS with ≥2 male partners in the past 6 months | ||

| No e | 80 | (69.57) |

| Yes | 33 | (28.70) |

| Alcohol or drug use immediately before or during sex in the past 6 months | ||

| No | 84 | (73.04) |

| Yes | 31 | (26.96) |

| PrEP use for HIV prevention | ||

| Previously used or currently using f | 57 | (49.57) |

| Never used | 57 | (49.57) |

| Tested for HIV in the past year | ||

| No g | 32 | (27.83) |

| Yes | 83 | (72.17) |

| Tested for STIs in the past year | ||

| No h | 47 | (40.87) |

| Yes | 68 | (59.13) |

Note. Numbers might not add to total due to missing data. CAS = condomless anal sex; GBMSM = gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men; PrEP = pre-exposure prophylaxis; STI = sexually transmitted infection.

Mean = 35 years, median = 33 years, minimum = 22 years, maximum = 57 years. bIncludes 7 Pakistani, 2 Nepali, 1 Sri Lankan, 1 Bangladeshi, and 1 Sindhi. cIncludes 5 insured under Medicare or Medicaid, 5 insured under the Affordable Care Act, 1 insured under the Veterans Affairs health plan, 2 insured under some other health plan, and 1 not insured under any health plan. dIncludes 10 bisexual, 2 pansexual, 2 queer, and 1 questioning. eIncludes 47 who did not engage in CAS and 33 who engaged in CAS with 1 male partner in the past 6 months. fIncludes 20 who had previously used PrEP and 37 who were using PrEP at the time of the survey. gIncludes 9 who had never been tested for HIV. hIncludes 23 who had never been tested for STIs.

Patterns of HIV Testing

Nine of 115 (7.83%) participants reported never being tested for HIV. Of the 106 (92.17%) who reported ever being tested, 51 (48.11%) tested in the past 3 months, 15 (14.15%) tested 3–6 months ago, 17 (16.04%) tested 6 months–1 year ago, 10 (9.43%) tested 1–2 years ago, and 13 (12.26%) tested more than 2 years ago. The majority received their most recent HIV test at a private doctor’s office (n = 64, 60.38%), followed by a community health center (n = 17, 16.04%), home or other private location (n = 7, 6.60%), a school or college clinic (n = 6, 5.66%), an urgent care center or walk-in clinic (n = 5, 4.72%), an HIV or STI testing center (n = 3, 2.83%), a mobile testing unit (n = 3, 2.83%), and a hospital emergency room (n = 1, 0.94%). Regarding the frequency of HIV testing, 37 (34.91%) tested every 3 months, 24 (22.64%) tested every 6 months, 14 (13.21%) tested every year, 16 (15.09%) tested every time they thought they might have been exposed, and 15 (14.15%) did not test regularly.

Patterns of STI Testing

Twenty-three of 115 (20.00%) participants reported never being tested for STIs. Of the 92 (80.00%) who reported ever being tested, 40 (43.48%) tested in the past 3 months, 14 (15.22%) tested 3–6 months ago, 14 (15.22%) tested 6 months–1 year ago, 9 (9.78%) tested 1–2 years ago, and 15 (16.30%) tested more than 2 years ago. The majority received their most recent HIV test at a private doctor’s office (n = 59, 64.13%), followed by a community health center (n = 17, 18.48%), an urgent care center or walk-in clinic (n = 5, 5.43%), a school or college clinic (n = 5, 5.43%), an HIV or STI testing center (n = 3, 3.26%), a hospital emergency room (n = 1, 1.09%), a mobile testing unit (n = 1, 1.09%), and home or other private location (n = 1, 1.09%). Regarding the frequency of STI testing, 34 (36.96%) tested every 3 months, 17 (18.48%) tested every 6 months, 10 (10.87%) tested every year, 11 (11.96%) tested every time they thought they might have been exposed, and 20 (21.74%) did not test regularly.

Variations in Past-Year HIV Testing

Table 2 presents variations in past-year HIV testing across strata of demographic and behavioral characteristics. Participants aged ≥35 years (versus <35 years) and those who were partnered (versus those who were single) were less likely to have been tested for HIV in the past year. However, the prevalence of past-year HIV testing was higher among those who had two or more male sex partners in the past 6 months (versus those who did not), those who had CAS with two or more male partners in the past 6 months (versus those who did not), and those who had used alcohol or drugs immediately before or during sex in the past 6 months (versus those who did not). Participants who had never used PrEP (versus those who had previously used or were currently using PrEP) were less likely to have been tested for HIV in the past year.

Table 2.

Variations in Past-Year HIV Testing Among 115 South Asian GBMSM in the United States, April to July 2022

| Characteristic | Tested for HIV in the past year (n = 83) | Did not test for HIV in the past year (n = 32) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | PR | (95% CI) | |

| Age | ||||||

| <35 years | 52 | (81.25) | 12 | (18.75) | ref. | |

| ≥35 years | 31 | (60.78) | 20 | (39.22) | 0.75 | [0.58, 0.96] a |

| Ethnic origin | ||||||

| Indian | 74 | (71.84) | 29 | (28.16) | ref. | |

| Other | 9 | (75.00) | 3 | (25.00) | 1.04 | [0.74, 1.48] |

| Educational level | ||||||

| Bachelor’s degree or lower | 25 | (80.65) | 6 | (19.35) | ref. | |

| Master’s degree or higher | 58 | (69.05) | 26 | (30.95) | 0.86 | [0.68, 1.07] |

| Employment status | ||||||

| Working full time or part time | 70 | (72.16) | 27 | (27.84) | ref. | |

| Studying or not employed | 13 | (72.22) | 5 | (27.78) | 1.00 | [0.73, 1.37] |

| Health insurance coverage | ||||||

| Private health plan | 73 | (72.28) | 28 | (27.72) | ref. | |

| Other | 10 | (71.43) | 4 | (28.57) | 0.99 | [0.69, 1.41] |

| Sexual orientation | ||||||

| Gay | 71 | (71.00) | 29 | (29.00) | ref. | |

| Other | 12 | (80.00) | 3 | (20.00) | 1.13 | [0.85, 1.49] |

| Place of birth | ||||||

| United States | 22 | (78.57) | 6 | (21.43) | ref. | |

| Outside the United States | 61 | (70.11) | 26 | (29.89) | 0.89 | [0.70, 1.13] |

| Relationship status | ||||||

| Single | 48 | (80.00) | 12 | (20.00) | ref. | |

| Partnered | 33 | (62.26) | 20 | (37.74) | 0.78 | [0.61, 0.99] a |

| Number of male sex partners in the past 6 months | ||||||

| 1 | 20 | (46.51) | 23 | (53.49) | ref. | |

| ≥2 | 63 | (87.50) | 9 | (12.50) | 1.88 | [1.35, 2.62] b |

| CAS with ≥2 male partners in the past 6 months | ||||||

| No | 49 | (61.25) | 31 | (38.75) | ref. | |

| Yes | 32 | (96.97) | 1 | (3.03) | 1.58 | [1.32, 1.90] b |

| Alcohol or drug use immediately before or during sex in the past 6 months | ||||||

| No | 56 | (66.67) | 28 | (33.33) | ref. | |

| Yes | 27 | (87.10) | 4 | (12.90) | 1.31 | [1.07, 1.60] b |

| PrEP use for HIV prevention | ||||||

| Previously used or currently using | 52 | (91.23) | 5 | (8.77) | ref. | |

| Never used | 30 | (52.63) | 27 | (47.37) | 0.58 | [0.45, 0.75] b |

Note. Numbers might not add to the total due to missing data. CAS = condomless anal sex; CI = confidence interval; GBMSM = gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men; PR = prevalence ratio; PrEP = pre-exposure prophylaxis.

Statistically significant association (p < .05). bStatistically significant association (p < .01).

Variations in Past-Year STI Testing

Table 3 presents variations in past-year STI testing across strata of demographic and behavioral characteristics. Participants aged ≥35 years (versus <35 years) and those who were born outside the United States (versus those who were born in the United States) were less likely to have been tested for STIs in the past year. However, the prevalence of past-year STI testing was higher among those who had two or more male sex partners in the past 6 months (versus those who did not) and those who had CAS with two or more male partners in the past 6 months (versus those who did not). Participants who had never used PrEP (versus those who had previously used or were currently using PrEP) were less likely to have been tested for STIs in the past year.

Table 3.

Variations in Past-Year STI Testing Among 115 South Asian GBMSM in the United States, April to July 2022.

| Characteristic | Tested for STIs in the past year (n = 68) | Did not test for STIs in the past year (n = 47) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | PR | (95% CI) | |

| Age | ||||||

| <35 years | 44 | (68.75) | 20 | (31.25) | ref. | |

| ≥35 years | 24 | (47.06) | 27 | (52.94) | 0.68 | [0.49, 0.96] a |

| Ethnic origin | ||||||

| Indian | 61 | (59.22) | 42 | (40.78) | ref. | |

| Other | 7 | (58.33) | 5 | (41.67) | 0.99 | [0.59, 1.63] |

| Educational level | ||||||

| Bachelor’s degree or lower | 20 | (64.52) | 11 | (35.48) | ref. | |

| Master’s degree or higher | 48 | (57.14) | 36 | (42.86) | 0.89 | [0.64, 1.22] |

| Employment status | ||||||

| Working full time or part time | 58 | (59.79) | 39 | (40.21) | ref. | |

| Studying or not employed | 10 | (55.56) | 8 | (44.44) | 0.93 | [0.60, 1.45] |

| Health insurance coverage | ||||||

| Private health plan | 62 | (61.39) | 39 | (38.61) | ref. | |

| Other | 6 | (42.86) | 8 | (57.14) | 0.70 | [0.37, 1.30] |

| Sexual orientation | ||||||

| Gay | 61 | (61.00) | 39 | (39.00) | ref. | |

| Other | 7 | (46.67) | 8 | (53.33) | 0.77 | [0.44, 1.34] |

| Place of birth | ||||||

| United States | 21 | (75.00) | 7 | (25.00) | ref. | |

| Outside the United States | 47 | (54.02) | 40 | (45.98) | 0.72 | [0.54, 0.96] a |

| Relationship status | ||||||

| Single | 38 | (63.33) | 22 | (36.67) | ref. | |

| Partnered | 28 | (52.83) | 25 | (47.17) | 0.83 | [0.61, 1.15] |

| Number of male sex partners in the past 6 months | ||||||

| 1 | 15 | (34.88) | 28 | (65.12) | ref. | |

| ≥2 | 53 | (73.61) | 19 | (26.39) | 2.11 | [1.37, 3.25] b |

| CAS with ≥2 male partners in the past 6 months | ||||||

| No | 38 | (47.50) | 42 | (52.50) | ref. | |

| Yes | 29 | (87.88) | 4 | (12.12) | 1.85 | [1.42, 2.41] b |

| Alcohol or drug use immediately before or during sex in the past 6 months | ||||||

| No | 47 | (55.95) | 37 | (44.05) | ref. | |

| Yes | 21 | (67.74) | 10 | (32.26) | 1.21 | [0.89, 1.65] |

| PrEP use for HIV prevention | ||||||

| Previously used or currently using | 45 | (78.95) | 12 | (21.05) | ref. | |

| Never used | 22 | (38.60) | 35 | (61.40) | 0.49 | [0.34, 0.70] b |

Note. Numbers might not add to the total due to missing data. CAS = condomless anal sex; CI = confidence interval; GBMSM = gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men; PR = prevalence ratio; PrEP = pre-exposure prophylaxis; STI = sexually transmitted infection.

Statistically significant association (p < .05). bStatistically significant association (p < .01).

Discussion

To our knowledge, Ujala is the first study to investigate patterns of HIV and STI testing specifically among South Asian GBMSM in the United States. Results indicate that despite being at risk for HIV and STIs, many members of this subgroup are not being tested at least annually in accordance with current national recommendations (DiNenno et al., 2017; Workowski et al., 2021). More than one in four participants had not been tested for HIV, and more than two in five participants had not been tested for STIs in the past year. Both these statistics are comparable to recent national estimates for GBMSM (CDC, 2023; de Voux et al., 2019). It is important to bear in mind that our study was conducted from April to July 2022, and participants were asked about their patterns of HIV and STI testing during the preceding couple of years when many individuals delayed or avoided seeking health care services due to COVID-19-related concerns (Moitra et al., 2022), and many health departments were forced to redeploy staff and resources from sexual health initiatives to COVID-19 mitigation efforts (Kuehn, 2022; Wright et al., 2022). The prevalence of past-year HIV and STI testing was lower among participants aged ≥35 years and those who had never used PrEP. Participants who were partnered were less likely to have been tested for HIV, and those who were born outside the United States were less likely to have been tested for STIs in the past year. It is also concerning that almost 8% and 20% of participants had never been tested for HIV or STIs, respectively. Findings from our study highlight inadequacies in domestic HIV- and STI-prevention efforts with respect to adequately engaging sexually active South Asian GBMSM and suggest that some segments of this subgroup may benefit from targeted outreach.

Our result that participants aged ≥35 years were less likely to have been tested for HIV and STIs in the past year is consistent with other studies conducted in the United States involving GBMSM of multiple races/ethnicities (Schumacher et al., 2020; Spensley et al., 2022). Middle-aged and older GBMSM tend to underestimate their risk for HIV and STIs compared to younger GBMSM (Jacobs et al., 2010; Kahle et al., 2018; Klein & Tilley, 2012) and might not be as motivated to seek regular testing. Semi-structured interviews with health care providers have also identified ageism as a factor that can result in some providers overlooking their patients’ vulnerability to HIV and STIs (Davis et al., 2016). Misconceptions and stereotypes about sex and aging, such as a progressive reduction in sexual interest or activity (Drumhiller et al., 2020; Tillman & Mark, 2015), may serve as impediments to offering regular testing to middle-aged and older GBMSM in health care settings. Future research is needed to determine the extent to which this gap in testing is problematic and its root causes.

Analogous to previous research (Stephenson et al., 2015), our study found that the prevalence of past-year HIV testing was lower among participants who were partnered. A similar result was observed for past-year STI testing, but it was not statistically significant at an α-level of .05. Qualitative work indicates that partnered GBMSM perceive themselves to be at reduced risk of HIV and STIs compared to their single counterparts (Shaver et al., 2018). Prominent theories of health behavior posit that one’s perceived susceptibility to a disease can influence the adoption of health-protective actions (Ferrer & Klein, 2015; Pantalone et al., 2016). Lower risk perceptions among GBMSM have indeed been associated with a reduced likelihood of HIV testing (White & Stephenson, 2016). Partnered GBMSM, however, are not immune to the risk of HIV. Modeling studies have found that one-third to two-thirds of HIV transmissions among GBMSM can be attributed to sex within relationships (Goodreau et al., 2012; Sullivan et al., 2009). This has prompted calls to scale up dyadic interventions for male couples such as couples HIV testing and counseling in which both partners test for HIV together and formulate a joint prevention plan (Chapin-Bardales et al., 2019; Purcell et al., 2014; Stephenson et al., 2016). Investments to support the implementation of dyadic interventions in routine health care settings could bolster the reach of HIV and STI testing services to partnered GBMSM of all races/ethnicities.

Our finding that GBMSM who were born outside the United States had a lower prevalence of past-year STI testing is concerning. A similar result was observed for past-year HIV testing, but it was not statistically significant at an α-level of .05. Migrants from low-income and middle-income countries to high-income countries frequently encounter a disruption of support networks, a sense of cultural confusion, and feelings of alienation, all of which may act as impediments to seeking HIV- and STI-prevention services (Bhugra & Becker, 2005; Ross et al., 2018). In a recent systematic review of sexual risk behaviors and HIV testing among immigrant and racial/ethnic minority GBMSM in North America and Europe, rates of testing among Asian GBMSM were lower in studies that had higher proportions of immigrants (Lewis & Wilson, 2017). National surveys also indicate that African American/Black and Hispanic/Latino immigrants to the United States have lower rates of HIV testing than those born in the United States (Ojikutu et al., 2016; Uzoeghelu et al., 2021). Further work is needed to understand the role of individual, interpersonal, and structural factors in shaping HIV and STI testing patterns among South Asian GBMSM immigrants.

Beyond the challenges associated with migration, research from other Western countries indicates that South Asian GBMSM face several intersecting stressors that could negatively impact their utilization of existing prevention services. Studies conducted in Australia (Gray et al., 2019; Smith, 2012), Canada (Nakamura et al., 2013; Ratti et al., 2000), New Zealand (Adams & Neville, 2020; Neville & Adams, 2016), and the United Kingdom (Jaspal & Siraj, 2011; Weston, 2003) report that South Asian GBMSM experience a heightened cultural taboo in relation to openly talking about their sexuality as this could bring irreparable dishonor upon their families. Concealment of one’s sexual identity could hinder frank discussions about sexual risk behaviors with health care providers (Jaspal, 2018), creating a missed opportunity to learn about the benefits of and engage in regular HIV and STI testing. Limited social interactions with other GBMSM could lead to feelings of marginalization, potentially leaving individuals with even fewer sources of sexual health information (Durrani & Sinacore, 2016). All these factors and more could be examined through future quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods research.

Participants in our study reported substantial engagement in sexual risk behaviors in the past 6 months. Specifically, almost two-thirds had two or more male sex partners, and more than a quarter had CAS with two or more male partners. A recent systematic review that synthesized more than 20 years of research on sexual risk behaviors among Asian GBMSM in Western countries (Shi Shiu et al., 2016) identified two studies (from a total of 13 quantitative studies conducted in the United States) that reported disaggregated data for different Asian ethnicities (Chae & Yoshikawa, 2008; Yoshikawa et al., 2004). Both found that the likelihood of having CAS was significantly higher for South Asian GBMSM than for East Asian GBMSM. Given that testing for HIV and STIs is the pathway to accessing prophylactic and therapeutic services depending upon individual needs and circumstances, it is encouraging that participants in our study who had recently engaged in sexual risk behaviors were more likely to have undergone past-year testing.

Of note, approximately one-third of our participants reported using PrEP at the time of the survey, which is comparable to overall national estimates for GBMSM (Finlayson et al., 2019; Mansergh et al., 2020). Our result that participants who had never used PrEP were less likely to have been tested for HIV and STIs in the past year is not surprising. Clinical practice guidelines recommend that HIV testing should be repeated at least every 3 months after oral PrEP initiation (i.e., before prescriptions are refilled or reissued) or every 2 months when long-acting injectable PrEP is being utilized (CDC, 2021). It is also recommended that GBMSM using PrEP should be tested for gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis every 3–6 months (Workowski et al., 2021). Unlike previous and current users of PrEP, GBMSM who have never used PrEP might be lacking the chance to engage in comprehensive conversations with health care providers about their sexual risk behaviors and learn about the full range of HIV- and STI-prevention options. Future studies with South Asian GBMSM could seek to contextualize PrEP use within an understanding of sexual risk behaviors to determine if more individuals may be eligible for PrEP than are receiving it, warranting targeted intervention for those at elevated risk of HIV.

Strengths of our study include recruiting a sample of sexually active South Asian GBMSM from all four census regions of the United States. Our use of CAPTCHA verification and “honeypot” questions helped ensure that our participants were real humans. Also, names and email addresses were verified by asking participants to reply to a test email to confirm its accuracy and functionality before disbursing the $25 Amazon e-gift card. However, our study is not without limitations. Ideally, all South Asian GBMSM in the general United States population should have an equal chance of participating, but our survey’s availability was restricted to those who were members of online South Asian LGBTQ+ groups and others in their network, thereby limiting the generalizability of our results. In addition, our data on the prevalence of past-year HIV and STI testing need to be considered in the context of COVID-19-related disruptions to the provision of sexual health services during and following the pandemic. Participants were not asked separate questions about their own or their male partners’ sex assigned at birth and current gender identity, and an assumption is made that all were cisgender. Finally, the cross-sectional nature of our data prevents us from commenting on the temporality of observed associations with past-year HIV and STI testing.

Conclusion

Our study sheds light on the rapidly expanding subgroup of South Asian GBMSM in the United States that has largely been ignored in HIV- and STI-prevention efforts. Our findings reveal gaps in past-year HIV and STI testing despite substantial engagement in sexual risk behaviors. Our analyses also identify demographic and behavioral segments of this subgroup that may benefit from targeted outreach. Undoubtedly, some South Asian GBMSM in the United States have unmet needs with respect to HIV and STI testing. Elucidating unique reasons and finding novel solutions should be prioritized in future research.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the study participants for their time and contributions to this research.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by discretionary funds awarded to the corresponding author from the School of Nursing, University of Michigan.

ORCID iD: Akshay Sharma  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7864-5464

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7864-5464

References

- Adams J., Neville S. (2020). Exploring talk about sexuality and living gay social lives among Chinese and South Asian gay and bisexual men in Auckland, New Zealand. Ethnicity and Health, 25(4), 508–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amola O., Grimmett M. A. (2015). Sexual identity, mental health, HIV risk behaviors, and internalized homophobia among black men who have sex with men. Journal of Counseling and Development, 93(2), 236–246. [Google Scholar]

- Bhugra D., Becker M. A. (2005). Migration, cultural bereavement and cultural identity. World Psychiatry, 4(1), 18–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budiman A., Ruiz N. (2021). Pew Research Center: Key facts about Asian origin groups in the U.S. Retrieved March 10, 2023, from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/04/29/key-facts-about-asian-origin-groups-in-the-u-s/

- CDC. (2020). Surveillance systems. Retrieved March 10, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/surveillance/systems/index.html

- CDC. (2021). Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States—2021 update. Retrieved March 10, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2021.pdf

- CDC. (2022. a). Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas 2020. Retrieved March 10, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance/vol-33/index.html

- CDC. (2022. b). Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2020. Retrieved March 10, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2020/default.htm

- CDC. (2022. c). STD Surveillance Network (SSuN). Retrieved March 10, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/std/ssun/default.htm

- CDC. (2023). HIV infection risk, prevention, and testing behaviors among men who have sex with men—National HIV Behavioral Surveillance, 13 U.S. cities, 2021. Retrieved March 10, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance-special-reports/no-31/index.html

- Chae D. H., Yoshikawa H. (2008). Perceived group devaluation, depression, and HIV-risk behavior among Asian gay men. Health Psychology, 27(2), 140–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapin-Bardales J., Rosenberg E. S., Sullivan P. S., Jenness S. M., Paz-Bailey G. (2019). Trends in number and composition of sex partners among men who have sex with men in the United States, National HIV behavioral surveillance, 2008–2014. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 81(3), 257–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K. H., Operario D., Gregorich S. E., McFarland W., MacKellar D., Valleroy L. (2005). Substance use, substance choice, and unprotected anal intercourse among young Asian American and Pacific Islander men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention, 17(5), 418–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis T., Teaster P. B., Thornton A., Watkins J. F., Alexander L., Zanjani F. (2016). Primary care providers’ HIV prevention practices among older adults. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 35(12), 1325–1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Voux A., Bernstein K. T., Kirkcaldy R. D., Zlotorzynska M., Sanchez T. (2019). Self-reported extragenital chlamydia and gonorrhea testing in the past 12 months among men who have sex with men in the United States—American Men’s Internet Survey, 2017. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 46(9), 563–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz J. E., Schrimshaw E. W., Tieu H.-V., Nandi V., Koblin B. A., Frye V. (2020). Acculturation as a moderator of HIV risk behavior correlates among Latino men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(6), 2029–2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiNenno E. A., Delaney K. P., Pitasi M. A., MacGowan R., Miles G., Dailey A., Courtenay-Quirk C., Byrd K., Thomas D., Brooks J. T., Daskalakis D., Collins N. (2022). HIV testing before and during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, 2019-2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 71(25), 820–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiNenno E. A., Prejean J., Irwin K., Delaney K. P., Bowles K., Martin T., Tailor A., Dumitru G., Mullins M. M., Hutchinson A. B., Lansky A. (2017). Recommendations for HIV screening of gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men—United States, 2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66, 830–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do T. D., Chen S., McFarland W., Secura G. M., Behel S. K., MacKellar D. A., Valleroy L. A., Cho K.-H. (2005). HIV testing patterns and unrecognized HIV infection among young Asian and Pacific Islander men who have sex with men in San Francisco. AIDS Education and Prevention, 17(6), 540–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do T. D., Hudes E. S., Proctor K., Han C.-S., Choi K.-H. (2006). HIV testing trends and correlates among young Asian and Pacific Islander men who have sex with men in two US cities. AIDS Education and Prevention, 18(1), 44–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drumhiller K., Geter A., Elmore K., Gaul Z., Sutton M. Y. (2020). Perceptions of patient HIV risk by primary care providers in high-HIV prevalence areas in the Southern United States. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 34(3), 102–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrani S., Sinacore A. L. (2016). South Asian-Canadian gay men and HIV: Social, cultural, and psychological factors that promote health. Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 50(2), 164–179. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer R. A., Klein W. M. (2015). Risk perceptions and health behavior. Current Opinion in Psychology, 5, 85–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlayson T., Cha S., Xia M., Trujillo L., Denson D., Prejean J., Kanny D., Wejnert C., Abrego M., Al-Tayyib A. (2019). Changes in HIV preexposure prophylaxis awareness and use among men who have sex with men—20 Urban areas, 2014 and 2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(27), 597–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghabrial M. A. (2017). “Trying to figure out where we belong”: Narratives of racialized sexual minorities on community, identity, discrimination, and health. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 14(1), 42–55. [Google Scholar]

- Goodreau S. M., Carnegie N. B., Vittinghoff E., Lama J. R., Sanchez J., Grinsztejn B., Koblin B. A., Mayer K. H., Buchbinder S. P. (2012). What drives the US and Peruvian HIV epidemics in men who have sex with men (MSM)? PLOS ONE, 7(11), Article e50522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray C., Lobo R., Narciso L., Oudih E., Gunaratnam P., Thorpe R., Crawford G. (2019). Why I can’t, won’t or don’t test for HIV: Insights from Australian migrants born in sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia and Northeast Asia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(6), 1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart T. A., Sharvendiran R., Chikermane V., Kidwai A., Grace D. (2021). At the intersection of homophobia and racism: Sociocultural context and the sexual health of South Asian Canadian gay and bisexual men. Stigma and Health. Advance online publication. 10.1037/sah0000295 [DOI]

- Heijman T., Zuure F., Stolte I., Davidovich U. (2017). Motives and barriers to safer sex and regular STI testing among MSM soon after HIV diagnosis. BMC Infectious Diseases, 17(1), 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HHS. (2022. a). Ending the HIV epidemic in the U.S. overview. Retrieved March 10, 2023, from https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/ending-the-hiv-epidemic/overview

- HHS. (2022. b). STI national strategic plan overview. Retrieved March 10, 2023, from https://www.hhs.gov/programs/topic-sites/sexually-transmitted-infections/plan-overview/index.html

- Hoots B. E., Torrone E. A., Bernstein K. T., Paz-Bailey G., Group N. S. (2018). Self-reported chlamydia and gonorrhea testing and diagnosis among men who have sex with men—20 US cities, 2011 and 2014. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 45(7), 469–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs R. J., Fernandez M. I., Ownby R. L., Bowen G. S., Hardigan P. C., Kane M. N. (2010). Factors associated with risk for unprotected receptive and insertive anal intercourse in men aged 40 and older who have sex with men. Aids Care, 22(10), 1204–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaspal R. (2017). Coping with perceived ethnic prejudice on the gay scene. Journal of LGBT Youth, 14(2), 172–190. [Google Scholar]

- Jaspal R. (2018). Enhancing sexual health, self-identity and wellbeing among men who have sex with men: A guide for practitioners. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Jaspal R., Siraj A. (2011). Perceptions of “coming out” among British Muslim gay men. Psychology and Sexuality, 2(3), 183–197. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffries W. L., Marks G., Lauby J., Murrill C. S., Millett G. A. (2013). Homophobia is associated with sexual behavior that increases risk of acquiring and transmitting HIV infection among black men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior, 17(4), 1442–1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahle E. M., Sharma A., Sullivan S. P., Stephenson R. (2018). HIV prioritization and risk perception among an online sample of men who have sex with men in the United States. American Journal of Men’s Health, 12(4), 676–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein H., Tilley D. L. (2012). Perceptions of HIV risk among internet-using, HIV-negative barebacking men. American Journal of Men’s Health, 6(4), 280–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobrak P., Remien R. H., Myers J. E., Salcuni P., Edelstein Z., Tsoi B., Sandfort T. (2022). Motivations and barriers to routine HIV testing among men who have sex with men in New York City. AIDS and Behavior, 26(11), 3563–3575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn B. M. (2022). Reduced HIV testing and diagnoses during COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American Medical Association, 328(6), 519–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis N. M., Wilson K. (2017). HIV risk behaviours among immigrant and ethnic minority gay and bisexual men in North America and Europe: A systematic review. Social Science and Medicine, 179, 115–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd L. S., Faust M., Roque J. S., Loue S. (1999). A pilot study of immigration status, homosexual self-acceptance, social support, and HIV reduction in high risk Asian and Pacific Islander men. Journal of Immigrant Health, 1, 115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas A., Murray E., Kinra S. (2013). Heath beliefs of UK South Asians related to lifestyle diseases: A review of qualitative literature. Journal of Obesity, 2013, 827674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansergh G., Mayer K., Hirshfield S., Stephenson R., Sullivan P. (2020). HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis medication sharing among HIV-negative men who have sex with men. JAMA Network Open, 3(9), e2016256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenney J., Sullivan P. S., Bowles K. E., Oraka E., Sanchez T. H., DiNenno E. (2018). HIV risk behaviors and utilization of prevention services, urban and rural men who have sex with men in the United States: Results from a national online survey. AIDS and Behavior, 22(7), 2127–2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeown E., Nelson S., Anderson J., Low N., Elford J. (2010). Disclosure, discrimination and desire: Experiences of Black and South Asian gay men in Britain. Culture, Health and Sexuality, 12(7), 843–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno Y., Borkowf C., Millett G. A., Bingham T., Ayala G., Stueve A. (2012). Homophobia and racism experienced by Latino men who have sex with men in the United States: Correlates of exposure and associations with HIV risk behaviors. AIDS and Behavior, 16(3), 724–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moitra E., Tao J., Olsen J., Shearer R. D., Wood B. R., Busch A. M., LaPlante A., Baker J. V., Chan P. A. (2022). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on HIV testing rates across four geographically diverse urban centres in the United States: An observational study. The Lancet Regional Health-Americas, 7, 100159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura N., Chan E., Fischer B. (2013). “Hard to crack”: Experiences of community integration among first- and second-generation Asian MSM in Canada. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 19(3), 248–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neville S., Adams J. (2016). Views about HIV/STI and health promotion among gay and bisexual Chinese and South Asian men living in Auckland, New Zealand. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 11(1), 30764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojikutu B. O., Mazzola E., Fullem A., Vega R., Landers S., Gelman R. S., Bogart L. M. (2016). HIV testing among Black and Hispanic immigrants in the United States. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 30(7), 307–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantalone D. W., Puckett J. A., Gunn H. A. (2016). Psychosocial factors and HIV prevention for gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 10(2), 109–122. [Google Scholar]

- Perez A., Santamaria E. K., Operario D. (2018). A systematic review of behavioral interventions to reduce condomless sex and increase HIV testing for Latino MSM. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 20, 1261–1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell D. W., Mizuno Y., Smith D. K., Grabbe K., Courtenay-Quirk C., Tomlinson H., Mermin J. (2014). Incorporating couples-based approaches into HIV prevention for gay and bisexual men: Opportunities and challenges. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43(1), 35–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos S. R., Nelson L. E., Jones S. G., Ni Z., Turpin R. E., Portillo C. J. (2021). A state of the science on HIV prevention over 40 years among black and Hispanic/Latinx communities. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care: JANAC, 32(3), 253–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratti R., Bakeman R., Peterson J. (2000). Correlates of high-risk sexual behaviour among Canadian men of South Asian and European origin who have sex with men. Aids Care, 12(2), 193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendina H. J., Jimenez R. H., Grov C., Ventuneac A., Parsons J. T. (2014). Patterns of lifetime and recent HIV testing among men who have sex with men in New York City who use Grindr. AIDS and Behavior, 18, 41–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross J., Cunningham C. O., Hanna D. B. (2018). HIV outcomes among migrants from low- and middle-income countries living in high-income countries: A review of recent evidence. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases, 31(1), 25–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher C., Wu L., Chandran A., Fields E., Price A., Greenbaum A., Jennings J. M., Collaborative I. P., Page K., Davis M. (2020). Sexually transmitted infection screening among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men prescribed pre-exposure prophylaxis in Baltimore City, Maryland. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 71(10), 2637–2644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro J., Vives G. (1999). Demographic and attitudinal variables related to high-risk behaviors in Asian males who have sex with other men. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 13(11), 667–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A., Gandhi M., Sallabank G., Merrill L., Stephenson R. (2022). Study evaluating self-collected specimen return for HIV, bacterial STI, and potential pre-exposure prophylaxis adherence testing among sexual minority men in the United States. American Journal of Men’s Health, 16(4), 15579883221115591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaver J., Freeland R., Goldenberg T., Stephenson R. (2018). Gay and bisexual men’s perceptions of HIV risk in various relationships. American Journal of Men’s Health, 12(4), 655–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Shiu C., Voisin D. R., Chen W.-T., Lo Y.-A., Hardestry M., Nguyen H. (2016). A synthesis of 20 years of research on sexual risk taking among Asian/Pacific Islander men who have sex with men in western countries. American Journal of Men’s Health, 10(3), 170–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G. (2012). Sexuality, space and migration: South Asian gay men in Australia. New Zealand Geographer, 68(2), 92–100. [Google Scholar]

- Souleymanov R., Brennan D. J., George C., Utama R., Ceranto A. (2020). Experiences of racism, sexual objectification and alcohol use among gay and bisexual men of colour. Ethnicity and Health, 25(4), 525–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spensley C. B., Plegue M., Seda R., Harper D. M. (2022). Annual HIV screening rates for HIV-negative men who have sex with men in primary care. PLOS ONE, 17(7), Article e0266747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson R., Grabbe K. L., Sidibe T., McWilliams A., Sullivan P. S. (2016). Technical assistance needs for successful implementation of couples HIV testing and counseling (CHTC) intervention for male couples at US HIV testing sites. AIDS and Behavior, 20(4), 841–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson R., White D., Darbes L., Hoff C., Sullivan P. (2015). HIV testing behaviors and perceptions of risk of HIV infection among MSM with main partners. AIDS and Behavior, 19(3), 553–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subedi R., Kaphle S., Adhikari M., Dhakal Y., Khadka M., Duwadi S., Tamang S., Shakya S. (2022). First call, home: Perception and practice around health among South Asian migrants in Melbourne, Australia. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 28(1), 40–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan P. S., Salazar L., Buchbinder S., Sanchez T. H. (2009). Estimating the proportion of HIV transmissions from main sex partners among men who have sex with men in five US cities. AIDS, 23(9), 1153–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton M. Y., Martinez O., Brawner B. M., Prado G., Camacho-Gonzalez A., Estrada Y., Payne-Foster P., Rodriguez-Diaz C. E., Hussen S. A., Lanier Y. (2021). Vital voices: HIV prevention and care interventions developed for disproportionately affected communities by historically underrepresented, early-career scientists. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 8, 1456–1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamhane A. R., Westfall A. O., Burkholder G. A., Cutter G. R. (2016). Prevalence odds ratio versus prevalence ratio: Choice comes with consequences. Statistics in Medicine, 35(30), 5730–5735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillman J. L., Mark H. D. (2015). HIV and STI testing in older adults: An integrative review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24(15–16), 2074–2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzoeghelu U., Bogart L. M., Mahoney T. F., Ojikutu B. O. (2021). Association between HIV testing and HIV-related risk behaviors among US and non-US born Black individuals living in the US: Results from the National Survey on HIV in the Black Community (NSHBC). Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 23, 1152–1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valverde E. E., Oster A. M., Xu S., Wertheim J. O., Hernandez A. L. (2017). HIV transmission dynamics among foreign-born persons in the United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 76(5), 445–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent W., McFarland W., Raymond H. F. (2017). What factors are associated with receiving a recommendation to get tested for HIV by health care providers among men who have sex with men? Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 75(Suppl. 3), S357–S362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter S. D. (2000). Choice of effect measure for epidemiological data. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 53(9), 931–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston H. (2003). Public honour, private shame and HIV: Issues affecting sexual health service delivery in London’s South Asian communities. Health and Place, 9(2), 109–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White D., Stephenson R. (2016). Correlates of perceived HIV prevalence and associations with HIV testing behavior among men who have sex with men in the United States. American Journal of Men’s Health, 10(2), 90–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong F. Y., Nehl E. J., Han J. J., Huang Z. J., Wu Y., Young D., Ross M. W., Consortium M. S. (2012). HIV testing and management: Findings from a national sample of Asian/Pacific islander men who have sex with men. Public Health Reports, 127(2), 186–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workowski K. A., Bachmann L. H., Chan P. A., Johnston C. M., Muzny C. A., Park I., Reno H., Zenilman J. M., Bolan G. A. (2021). Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 70(4), 1–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright S. S., Kreisel K. M., Hitt J. C., Pagaoa M. A., Weinstock H. S., Thorpe P. G. (2022). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention–funded sexually transmitted disease programs. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 49(4), e61–e63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa H., Alan-David Wilson P., Chae D. H., Cheng J.-F. (2004). Do family and friendship networks protect against the influence of discrimination on mental health and HIV risk among Asian and Pacific Islander gay men? AIDS Education and Prevention, 16(1), 84–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]