Abstract

Objective:

Tobacco use is associated with mortality in low- and middle-income countries including India with dual burden of smoking and smokeless tobacco (SLT). Aligning with the FCTC, India has made substantial amendments in strengthening graphic warning under Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products Act (COTPA) for sections 7,8 9 and “Specified warning”. Compliance assessment studies are necessary to understand current status of implementation for packaging laws. This study aimed to assess the compliance of COTPA sections 7,8 9 and Cigarettes and other Tobacco Products (Packaging and Labelling) Third Amendment Rules, 2020 in Delhi.

Methods:

Cross-sectional study was conducted in two districts of Delhi selected by simple random sampling. Fifteen points of sales were selected from each district through purposive sampling and 57 smoking and smokeless tobacco products were collected with Indian and foreign origin. An observation checklist for product analysis was prepared and pack analysis done based on COTPA sections 7,8 and 9 along with Third Amendment,2020 which included pictures and warnings to be circulated in 2021.

Result:

Total 57 samples has smoking (49.1%), smokeless (50.9%) with no SLT product of foreign origin. SLT and foreign products had low compliance of Section 7 and third amendment 2020 rules which includes manufacturing date and origin. Indian smoking products were highly compliant to section 8 and 9 whereas foreign and SLT products showed low compliance to section 8. COTPA Third Amendment Rules (2020) compliance was seen in Indian products with regards to SW (68.4%), PW (61.4%) and quit line (78.9%) with no compliance at all for foreign products.

Conclusion:

Foreign brands and SLT products had low compliance with sections 7 and 8 of COTPA and its amendments (2020). Compliance with illicit trade and SW needs regulation and strict implementation of law for SLT products.

Key Words: Compliance, Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products Act, health warning, tobacco

Introduction

Tobacco use is associated with accelerated mortality among adults, especially in low- and middle-income countries, where the burden of tobacco-related illness and death is heaviest. More than 1 million adults die each year in India due to tobacco use accounting for 9.5% of overall deaths. India faces a dual burden of tobacco use in the form of smoking and smokeless tobacco (SLT). India is the world’s second leading consumer, the third largest producer, and the fifth largest exporter of tobacco products (Mishra et al., 2012). According to the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) (2016–17), the prevalence of smoking tobacco use is 10.38% and SLT use is 21.38% in India. Of all adults, 28.6% currently consume tobacco either in smoked or smokeless form, including 42.4% of men and 14.2% of women. The economic burden from tobacco accounts for more than 1% of India’s GDP. Addition to it, the direct health expenditures on treating tobacco-related diseases alone account for 5.3% of the total private and public health expenditures in India per year. This implies that for every INR 100 that is received as excise taxes from tobacco products, INR 816 of costs is imposed on society through its consumption. It establishes that tobacco consumption is a major resource drain on the national exchequer, and its effective regulation through comprehensive fiscal and non-fiscal policies is highly warranted. (John et al., 2021)

The World Health Organization (WHO) has been working internationally with different authorities to make guidelines, actions, and policies that averts and curtails tobacco use. In order to sustain a potent monitoring system, the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) was adopted by the World Health Assembly on 21 May 2003 and entered into force on 27 February 2005 of which India became the eighth country to ratify. FCTC has identified graphic health warning labels (HWLs) on product packaging as a cost-effective policy intervention to inform consumers about tobacco’s health risks. Graphic warnings can impact people with low levels of literacy. (WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, 2003). Given SLT and bidi consumers are more likely to have minimal formal schooling, graphic HWLs are particularly useful in these settings (Sorensen et al., 2005). Aligning with the FCTC guidelines, the Government of India has made substantial amendments in strengthening graphic HWLs under Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products Act (COTPA) for sections 7,8 9 and vied “Specified warning” (SW) as such warnings against the use of cigarettes or other tobacco products to be printed, painted or inscribed on packages of cigarettes or other tobacco products in such form and manner as may be prescribed by rules made under this Act. Most recently, the Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products Act (COTPA) set Specified Warning (SW) requirements to cover 85% of the principal display on both sides of all tobacco packages (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Notification G.S.R 182(E), 2008; Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Notification G.S.R 182(E), 2014). The efficacy of SW is influenced by several collective elements such as the size, position, content, and message design (Fong et al., 2009; Swayampakala et al., 2015). Also, to be effective in achieving its ultimate health goals, the HWL needs to be implemented as intended (Cohen et al., 2016).

As per Rule 5 of the Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products (Packaging and Labelling) Rules, the specified health warning on tobacco product packages shall be rotated every twenty-four months. Cigarettes and other Tobacco Products (Packaging and Labelling) Third Amendment Rules, 2020 has notified the new set of specified health warnings which should come into circulation from the 1st day of December 2020. In this regard, public notice has also been published for information to the stakeholders. (Cigarettes and other Tobacco Products (Packaging and Labelling) Third Amendment Rules, 2020).

SW effectively communicates the health hazards of tobacco use. Evidence shows that large graphic health warnings on tobacco packs are efficient in influencing customers and cost-effective. In India, tobacco product brands are local and vary by region. The depiction of SW would bring greater awareness and sensitization about the serious and adverse health consequences of tobacco use, especially among the youth, children, and the illiterate. Effective implementation of these rules depended on concerted efforts of all the concerned Ministries/ Departments of the Govt. of India as well as State Governments.

New Delhi, India, is the epicentre of the country in every aspect of government policy-making machinery. For a decade, it has been difficult to promote prospective tobacco control initiative in the state, and hence similar situation was apparent in other states as well. Recently, few studies that have assessed SW compliance in India were conducted in rural settings having an impression that SLT and bidis are consumed more in rural areas. After assessing the current burden and pattern of tobacco use in India, rigorous compliance assessment studies are crucial for understanding the current status of implementation of packaging laws. This study aimed to assess the compliance of tobacco products for Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products Act (COTPA) for sections 7,8 9 and Cigarettes and other Tobacco Products (Packaging and Labelling) Third Amendment Rules, 2020 in Delhi, India.

Materials and Methods

Study design and study settings: A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted from September to December 2021. There are 11 districts in Delhi out of which two districts were selected randomly using simple random sampling for data collection. These include the Central and East district.

Sampling method and sample size: Fifteen points of sales (POS) were selected from each district through purposive sampling and a total of 57 tobacco product samples for smoking and smokeless form were collected. Samples included Indian as well as foreign brands available at the POS in all available brands and sizes. The size which was most sold was considered for analysis. Once collected from any POS, the brand or type, or size was not again collected from the next POS if available.

Data collection: Training was conducted for data collectors regarding the collection of tobacco products and pack analysis for sections 7,8 and 9 of COTPA and Cigarettes and other Tobacco Products (Packaging and Labelling) Third Amendment Rules, 2020.

Data analysis: Pack analysis was done for all sides of the packaging of tobacco products for size, colour, clarity of pictorial and textual health warning known as Specified warning (SW), contents, location, and misleading descriptors. The front and back sides of the pack were considered as principal display areas (PDA) as per COTPA and analysed separately, as the front is more important for a user to focus on. The size of the SW on the PDA was calculated using a ruler as the area covered by the warning label (warning height x warning width) was divided by the PDA.

Misleading descriptors were considered as any promotional messages that directly or indirectly promote the consumption of any specific tobacco brand or type of tobacco in general or any statement that distracts the attention from a specified health warning.

An observation checklist for product analysis was prepared based on sections 7,8 and 9 of COTPA along with the Third Amendment,2020 which included pictures and warnings to be circulated in 2021. Data was recorded through direct observations of the trained investigators. Every collected sample of the product was analyzed as per the checklist. An individual investigator was coded for each sample and discrepancies were resolved after discussions with the Principal investigator and reviewing tobacco control law documents. This ensured the quality of data collection in a uniform pattern.

Statistical analysis

Data was assessed using Statistical Package for Social sciences (SPSS) version 26.0 and descriptive tests were applied.

Results

In this cross-sectional study, 30 POS were visited from two districts and a total of 57 samples of tobacco products were collected. Out of these 57 samples, 28 (49.1%) were smoking and 29 (50.9%) were SLT products. Among smoking products, 20 (85.96 %) were Indian products and 8 (14%) were foreign products. No SLT product of foreign origin was found during data collection (Table 1). Among all the Indian tobacco products maximum tobacco products 29 (59.2%) were SLT which includes Pan Masala with Tobacco 14 (48.3%), followed by Khaini 8 (27.6%), Tobacco with lime 4 (13.8%), Gul 2 (6.9%) and Khiwam 1 (3.4%). Among Indian smoking products, one-fourth i.e. 5 (25%) were Beedi and a maximum of 15 (75%) were cigarettes. All 8 foreign smoking tobacco products were cigarettes (Table 2).

Table 1.

Distribution of Collected Tobacco Products as per Country of Origin and Type of Tobacco Products

| Type of tobacco | Indian | Foreign | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking N (%) | 20 (40.8%) | 8 (100%) | 28 (49.1%) |

| Smokeless N (%) | 29 (59.1%) | 0 (0%) | 29 (50.9%) |

| Total N (%) | 49 (100%) | 8 (100%) | 57 (100%) |

Table 2.

Distribution of Indian Tobacco Products as Per Type of Tobacco product

| Type of product | Number (%) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking | Cigarettes | 15 (75%) | 20 (40.8%) |

| Beedi | 5 (25%) | ||

| Smokeless | Pan Masala with Tobacco | 14 (48.3%) | 29 (59.2%) |

| Khaini1 | 8 (27.6%) | ||

| Tobacco with lime | 4 (13.8%) | ||

| Gul | 2 (6.9%) | ||

| Kiwam2 | 1 (3.4%) | ||

| Total | 49 (100%) |

Table 3 explains the distribution of tobacco products according to various parameters under sections 7,8, and 9 of COTPA along with Cigarettes and other Tobacco Products (Packaging and Labelling) Third Amendment Rules, 2020 respectively.

Table 3.

Distribution of the Tobacco Products According to Information on Pack as Per COTPA Section 7,8 ,9 and Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products (Packaging and Labelling) Third Amendment Rules, 2020

| COTPA Section | Criteria for illicit product | Smoking | Smokeless | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indian brand N = 20 (%) |

Foreign brand N = 8 (%) |

Indian brand N = 29 (%) |

Total N =57 (%) |

||

| Section 7 | Name and address of the manufacturer | 17(85.0%) | 3 (37.5%) | 28 (96.6%) | 48 (84.2%) |

| Manufacturing date present on pack | 15(75.0%) | 1 (12.5%) | 7 (24.1%) | 23 (40.4%) | |

| Quantity of the product mentioned on the pack | 15(75.0%) | 7 (87.5%) | 20 (69.0%) | 42 (73.7%) | |

| The nicotine and Tar content mentioned on the pack | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (50.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (7.0%) | |

| Specified warning (SW) Present | 20(100%) | 4 (50.0%) | 29 (100%) | 53 (93.0%) | |

| Section 8 | No culturally specific references on the pack | 19(95.0%) | 8 (100%) | 28 (96.6%) | 55 (96.5%) |

| No misleading information on the pack | 16(80.0%) | 6 (75.0%) | 29 (100%) | 51 (89.5%) | |

| SW Present on both side | 19 (95.0%) | 1 (12.5%) | 25 (86.2%) | 45 (78.9%) | |

| SW Covered 85% of PDA | 9 (45.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (6.9%) | 11 (19.3%) | |

| 60% Pictorial Warning (PW) | 9 (45.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (10.3%) | 12 (21.1%) | |

| 25% Textual Warning (TW) | 9 (45.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (10.3%) | 12 (21.1%) | |

| Health warning position (before opening visible to consumer) | 18 (90.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 27 (93.1%) | 45 (78.9%) | |

| Size of SW (at least 3.5 cm x 4cm ) | 18 (90.0%) | 1 (12.5%) | 23 (79.3%) | 42 (73.7%) | |

| Cigarettes and other Tobacco Products (Packaging and Labelling) Third Amendment Rules, 2020 |

SW as per the current period | 16 (80.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 23 (79.3%) | 39 (68.4%) |

| PW resolution | 17 (85.0%) | 1 (12.5%) | 5 (17.2%) | 23 (40.4%) | |

| [minimum 300 DPI (Dots per inch)] | |||||

| PW images same as per current period | 14 (70.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 21 (72.4%) | 35 (61.4%) | |

| Quit line information present as per amendment | 18 (90.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 27 (93.1%) | 45 (78.9%) | |

| Section 9 | SW in Regional language | 5 (25.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 29 (100%) | 34 (59.6%) |

| SW in National language | 5 (25.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 29 (100%) | 34 (59.6%) | |

| SW in the English language | 20 (100%) | 4 (50.0%) | 29 (100%) | 53 (93.0%) | |

| SW in the foreign language | 1 (5.0%) | 2 (25.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (5.3%) | |

Location of manufacturing unit of tobacco is directly related to illicit trade of tobacco and hence COTPA ensures disclosure of place and date of manufacturing of tobacco product. Among total collected products, 48 (84.2%) disclosed the name and address of the manufacturer among which only 37.5% of foreign products showed compliance. The manufacturing date is important to abide by the Cigarettes and other Tobacco Products (Packaging and Labelling) Third Amendment Rules, 2020 in which SW changes on yearly basis. Only 23 products had manufacturing dates on them out of which compliance was very less for SLT (24.1%) and foreign (12.5%) tobacco products. Compliance with the disclosure of nicotine and tar content was very poor and found only in 7% of products that excluded all Indian smoking and SLT products. All Indian smoking and SLT products had SW whereas 50% of the foreign products were lacking these SW applicable in India.

Culturally specific references such as special images, symbols, colour, etc. were not found on 96.5% of products that interfere with SW or promote the brand of tobacco. Misleading information such as words suggesting flavour or reduced strength was not found in 89.5% of products, especially including all SLT products.

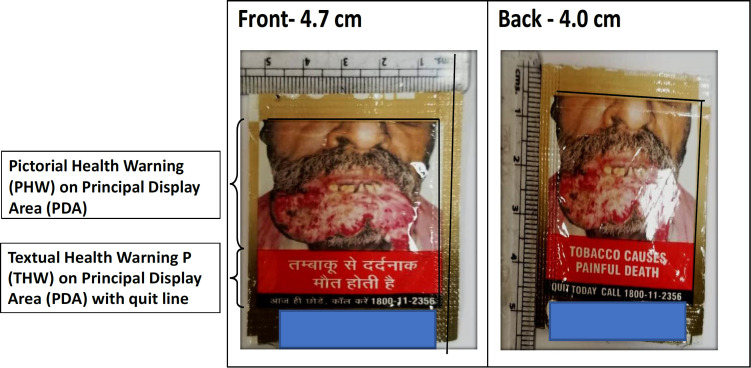

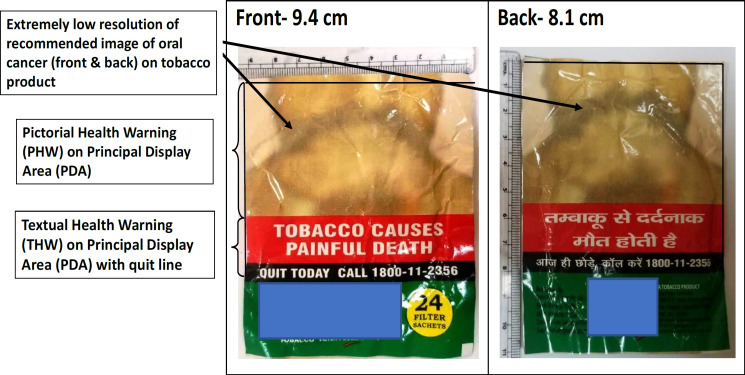

As per the provisions of Section 8 of COTPA, SW was present on both sides of the pack in 78.9% of products which included 86.2 % of SLT products. Indian smoking products were 95% compliant whereas only one foreign smoking product out of eight was compliant with SW being printed on both sides(for calculation of SW refer to Figures 1 and 2). As per the law, SW should cover 85% of PDA but only 21.1% of products were compliant with this among which foreign tobacco products and Indian SLT products were highly noncompliant. In the mentioned 85% SW on PDA, 60% should be Pictorial Warning (PW) and 25% should be Textual Warning (TW) but only 21.1% of products were compliant with this rule. Non-compliance regarding PW and TW was mainly seen in all foreign tobacco products with maximum (26/29) Indian SLT products. As per the law, SW should be positioned in a way on tobacco pack that before opening it should be visible to the consumer, and 78.9% of Indian products were compliant with this. SW should be of at least 3.5cm X 4 cm to which 73.7% (41/57) of Indian products and only 1 foreign product were compliant.

Figure 1.

Calculation of Specified Warning (SW = PHW+THW) on PDA of Tobacco Product and Resolution of the Image. The figure denotes the picture of oral cancer on lower lip

Figure 2.

Calculation of Specified Warning (SW = PHW+THW) on PDA of Tobacco Product and Resolution of the Image

As per the Cigarettes and other Tobacco Products (Packaging and Labelling) Third Amendment Rules (2020) Figure 3 shows images 1 (to be circulated for 12 months from 1st December 2020) and image 2 (should come into effect following the end of twelve months from the date of commencement of specified warning of Image 1.) with minimum 300 DPI (Dots per inch) resolution and Quitline information in specified colours. The SW for the current period was seen only on 68.4% of Indian products. PW resolution as per the rule was seen only in 23(40.4%) products. PW images same as per current period were seen in only 35(61.4%) Indian products. Quitline information as per amendment was seen on 45(78.9%) products. All foreign products were not compliant with the third amendment, 2020 except 1 which had PW resolution as per rule.

Figure 3.

Images to be in Crculation as Per Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products (Packaging and Labelling) Third Amendment Rules, 2020

As per section 9 of COTPA, 93% of products were having SW in the English language but only 59.6 % had SW in regional or national language as in Delhi both these languages are the same i.e Hindi. Only 25% of foreign products had SW in a foreign language whereas 50% of them had it in the English language.

Discussion

In this study compliance with sections 7,8 and 9 of COTPA and Cigarettes and other Tobacco Products (Packaging and Labelling) Third Amendment Rules, 2020 were assessed for 57 products collected from two districts of Delhi. It was observed that Indian markets had a similar distribution of smoking and smokeless products but foreign products were available only in the smoking form of tobacco.

As per section 7 of COTPA, all Indian tobacco products were compliant with regards to SW rules specified health warnings and textual health warnings whereas only 50% of foreign smoking products were compliant with SW for tobacco products which is in contrast to a study done by Chahar et al., (2015) in Delhi which showed least compliance of 22.2 % for health warnings by foreign brands whereas compliance of Indian products was 96.6 %. This difference might have been subjected to time and better implementation of regular amendments which were observed from 2015 onwards. This was also in similar lines to the study done by Goal et al., (2016) in Chandigarh, India which stated that 33.3% of foreign brands and 96% of Indian smoking brands were compliant with section 7 of COTPA.

Article 15 of WHO FCTC commits the signatory Parties to eliminate all forms of illicit trade in tobacco products. WHO has also come up with a protocol to eliminate the illicit trade of tobacco products (2021), which was adopted by Govt of India. Thus, it seems that the implementation of tobacco control policies is to be strengthened and needs further evaluation to identify how these foreign products enter the Indian markets. The implementation of the Protocol became difficult for the government because the tobacco industry opposes an increase in taxation with an increase in illicit trade throughout (Ross et al., 2021).

Although SW was present on both sides of 79% of products, it was not as per rules of section 8 of COTPA and its third amendment, 2020. Only 21.1% of products were compliant with SW covering 85% of PDA in the study which excluded all foreign products and maximum (93.1%) SLT products. 45% of Indian smoking products were compliant with 85% of SW rules which was found lower to compliance as stated in the study done by Chahar et al., (2015) in Delhi (59.2%). This finding was slightly lower than the compliance mentioned in the study done by Oswal et al (2010) stating that 60% of smoked products were compliant with 60% of the PW rule. This difference might have been due to the subjective measurement of SW(PW+TW) of PDA. The findings of the study done by Chaudhary et al., (2020) in Shimla states that compliance for SW covering appropriate position in the front panel of pack is 100% for smoking and 88.2% for SLT products which are similar to this study’s findings which has a compliance of 90% for smoking and 93.1 % for SLT products. The appropriate size of SW (minimum 3.5 X 4.5 cm) is found in 73.7 % of products but PW resolution as per regulation was found only in 40.4% of products which suggests that even if the PW is of appropriate size the resolution is not appropriate. This was similar to findings seen in Chahar et al., (2015) which state that 60% of products have size appropriate but the picture is distorted in 34.7% of products. Foreign smoking products were highly non-compliant to appropriate SW on PDA, 60% and 25% rule of warning, position size and resolution of health warning, and Quitline information.

80% of smoking and SLT products respectively are compliant with SW as per the current period and 70% of smoking and 72.4% of SLT products respectively are compliant to PW images as per the current period which are the amendments of section 8 of COTPA in 2020 (Cigarettes and other Tobacco Products (Packaging and Labelling) Third Amendment Rules, 2020).This study strongly suggests that the implementation of sections 7 and 8 needs to be strengthened to minimize the burden of tobacco use and illicit trade of products in Indian markets.

The language of textual health warning was English in 93% of products which was in accordance with the study done by Chahar et al in Delhi (2015) which stated 91.8% but higher than the study done in Chandigarh by Goel et al., (2016) which shows74.4%.

In conclusion, this study highlighted that, foreign brands of smoked tobacco and SLT products had very low compliance with sections 7 and 8 of COTPA and Cigarettes and other Tobacco Products (Packaging and Labelling) Third Amendment Rules, 2020. Compliance with SW needs regulation and strict implementation in the Indian markets as per the regular amendments, especially for SLT products. Reinforcement of tobacco control laws and efforts to curb the illicit trade in tobacco products should gain momentum to minimize the burden of tobacco in India.

Author Contribution Statement

AB contributed in study concept, design and intellectual content. CD contributed to literature search, data analysis, statistical analysis, manuscript preparation and editing. SG and MS contributed for Manuscript review. AS worked for data collection whereas AS and PB worked on data analysis..

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Miss Indu Arora and Mr Vinod for providing appropriate resources and help for packaging and storage of tobacco product samples collected from field.

Ethical Permission

This study was a part of larger study by name “Addressing Smokeless Tobacco and building Research Capacity In South Asia (ASTRA)” and ethical clearance was taken from Institutional ethics Committee, Maulana Azad Medical College, New Delhi.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- Ali I, Patthi B, Singla A, et al. Assessment of implementation and compliance of (COTPA) Cigarette and Other Tobacco Products Act (2003) in open places of Delhi. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020;9:3094–9. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_24_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chahar P, Karnani M, Mohanty VR. Communicating Risk: Assessing Compliance of Tobacco Products to Cigarettes and other Tobacco Products Act (Packaging and Labelling) Amendment Rules 2015 in Delhi, India. Contemp Clin Dent. 2019;10:417–22. doi: 10.4103/ccd.ccd_668_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary A, Thakur A, Chauhan T, et al. An assessment of compliance with the provisions of Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products Act 2003: Is Shimla a smoke-free city? Natl Med J India. 2020;33:335. doi: 10.4103/0970-258X.321141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cigarettes_and_other_Tobacco_Products_Packaging_and_Labelling_Third_Amendment_Rules_2020. (n.d.) [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JE, Brown J, Washington C, et al. Do cigarette health warning labels comply with requirements: A 14-country study. Prev Med. 2016;93:128–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Economic_Burden_of_Tobacco_Related_Diseases_in_India-Report.pdf. (n.d.) 2022. Retrieved February 24. https://nhm.gov.in/NTCP/Surveys-Reports-Publications/Economic_Burden_of_Tobacco_Related_Diseases_in_India-Report.pdf.

- Fong GT, Hammond D, Hitchman SC. The impact of pictures on the effectiveness of tobacco warnings. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:640–3. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.069575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel S, Sardana M, Jain N, Bakshi D. Descriptive evaluation of cigarettes and other tobacco products act in a North Indian city. Indian J Public Health. 2016;60:273. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.195858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Mathew B. Observational study to check the compliance of implementation of 85% graphic health warnings on tobacco products in India from April 1, 2016. Tob Induc Dis. 2018:16. [Google Scholar]

- Jandoo T, Mehrotra R. Tobacco control in India: Present scenario and challenges ahead. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2008;9:805–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John RM, Sinha P, Munish VG, Tullu FT. Economic Costs of Diseases and Deaths Attributable to Tobacco Use in India, 2017–2018. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021;23:294–301. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntaa154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark Goodchild, Praveen Sinha, Vineet Gill Munish, Fikru Tesfaye Tullu. Changes in the affordability of tobacco products in India during 2007/2008 to 2017/2018: A price-relative-to-income analysis. WHO South-East Asia J Public Health. 2020;9:73–81. doi: 10.4103/2224-3151.283001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra GA, Pimple SA, Shastri SS. An overview of the tobacco problem in India. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2012;33:139–45. doi: 10.4103/0971-5851.103139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswal KC, Pednekar MS, Gupta PC. Tobacco industry interference for pictorial warnings. Indian J Cancer. 2010;47:101–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.65318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai B, Bramhankar M. Tobacco use among Indian states: Key findings from the latest demographic health survey 2019–2020. Tob Prev Cessation. 2021;7:19. doi: 10.18332/tpc/132466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross H, Joossens L. Tackling illicit tobacco during COVID-19 pandemic. Tob Induc Dis. 2021;19:10. doi: 10.18332/tid/137086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraf S, Welding K, Iacobelli M, et al. Health Warning Label Compliance for Smokeless Tobacco Products and Bidis in Five Indian States. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2021;22:59–64. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2021.22.S2.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen G, Gupta PC, Pednekar MS. Social Disparities in Tobacco Use in Mumbai, India: The Roles of Occupation, Education, and Gender. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1003–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.045039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swayampakala K, Thrasher JF, Hammond D, et al. Pictorial health warning label content and smokers’ understanding of smoking-related risks—A cross-country comparison. Health Educ Res. 2015;30:35–45. doi: 10.1093/her/cyu022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control and World Health Organization. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Convention-Cadre de l’ OMS Pour La Lutte Antitabac. 2003. p. 36. [Google Scholar]