Key Points

Question

Does maternal intake of hen’s eggs at birth affect the risk of immunoglobulin E–mediated egg allergy in infants aged 12 months?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial involving 380 breastfed infants whose parents had an allergic disease, maternal consumption of 1 whole egg per day during the first 5 days after delivery did not affect egg allergy development and sensitization to egg white in the infants compared with complete egg avoidance by the mothers during the same period. No adverse effects were observed.

Meaning

The findings of this randomized clinical trial indicate that egg allergy development is unaffected by maternal egg consumption during the very early neonatal period.

Abstract

Importance

Egg introduction in infants at age 4 to 6 months is associated with a lower risk of immunoglobulin E–mediated egg allergy (EA). However, whether their risk of EA at age 12 months is affected by maternal intake of eggs at birth is unknown.

Objective

To determine the effect of maternal egg intake during the early neonatal period (0-5 days) on the development of EA in breastfed infants at age 12 months.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This multicenter, single-blind (outcome data evaluators), randomized clinical trial was conducted from December 18, 2017, to May 31, 2021, at 10 medical facilities in Japan. Newborns with at least 1 of 2 parents having an allergic disease were included. Neonates whose mothers had EA or were unable to consume breast milk after the age of 2 days were excluded. Data were analyzed on an intention-to-treat basis.

Interventions

Newborns were randomized (1:1) to a maternal egg consumption (MEC) group, wherein the mothers consumed 1 whole egg per day during the first 5 days of the neonate’s life, and a maternal egg elimination (MEE) group, wherein the mothers eliminated eggs from their diet during the same period.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was EA at age 12 months. Egg allergy was defined as sensitization to egg white or ovomucoid plus a positive test result in an oral food challenge or an episode of obvious immediate symptoms after egg ingestion.

Results

Of the 380 newborns included (198 [52.1%] female), 367 (MEC: n = 183; MEE: n = 184) were followed up for 12 months. On days 3 and 4 after delivery, the proportions of neonates with ovalbumin and ovomucoid detection in breast milk were higher in the MEC group than in the MEE group (ovalbumin: 10.7% vs 2.0%; risk ratio [RR], 5.23; 95% CI, 1.56-17.56; ovomucoid: 11.3% vs 2.0%; RR, 5.55; 95% CI, 1.66-18.55). At age 12 months, the MEC and MEE groups did not differ significantly in EA (9.3% vs 7.6%; RR, 1.22; 95% CI, 0.62-2.40) or sensitization to egg white (62.8% vs 58.7%; RR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.91-1.26). No adverse effects were reported.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this randomized clinical trial, EA development and sensitization to eggs were unaffected by MEC during the early neonatal period.

Trial Registration

UMIN Clinical Trials Registry: UMIN000027593

This randomized clinical trial examines the development of egg allergy and sensitization in breastfed infants whose mothers ate eggs in the first 5 days after delivery.

Introduction

The prevalence of food allergy is increasing,1,2,3,4,5 estimated at approximately 10% in children.4,5,6,7 Notably, the hen’s egg is one of the most common causative foods for food allergies and anaphylaxis.8,9,10,11 Thus, preventing egg allergy (EA) is important for children.

Oral tolerance induction to prevent EA and oral immunotherapy for patients with EA has shown promising results.12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20 For example, in several oral immunotherapy trials, although high-dose egg protein ingestion induced allergic symptoms, low-dose egg protein ingestion could induce tolerance with fewer allergic symptoms.17,18,19,20,21,22 In addition, although several randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and a meta-analysis reported that early consumption of eggs from age 3 to 6 months prevented EA,14,15,16,23 a certain number of infants had already developed EA at the time of enrollment.14,16,24,25,26,27 A case series study showed that EA had already developed by age 3 months.28 Based on these results, intervention earlier than age 3 to 6 months would be desirable for the primary prevention of EA.5

In 2019, the ABC (Atopy Induced by Breastfeeding or Cow’s Milk Formula) trial showed that consuming cow’s milk formula protein during the first 3 days of life increased the risk of milk allergy.29 Additionally, 2 cohort trials found that milk protein ingestion for 1 or 3 days after birth was associated with an increased risk of milk allergy.30,31 Generally, egg proteins secreted into breast milk as a result of the maternal egg intake are minuscule.32,33,34 Therefore, we hypothesized that administering eggs via breastfeeding during the early neonatal period (0-5 days) prevents EA, acting like spontaneous low-dose oral immunotherapy. To examine this hypothesis, this multicenter RCT was conducted to assess whether maternal egg consumption (MEC) or elimination by mothers in the first 5 days after delivery prevents infants’ EA.

Methods

Study Design and Ethics Approval

This multicenter, single-blind (outcome data evaluators) RCT was conducted from December 18, 2017, to May 31, 2021, at 10 facilities in Japan. The trial protocol is provided in Supplement 1. This study was conducted in accordance with the regulatory requirements and approved by the Central Ethical Review Committee for Clinical Research of the National Hospital Organization. Informed consent was obtained from the mother of each infant before participation in this study; financial compensation was not provided. Participants’ clinical data were managed using anonymized research identification. We followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline. Data were analyzed on an intention-to-treat basis.

Participants

Inclusion criteria were neonates with at least 1 of the 2 parents having a current medically diagnosed allergic disease (at least 1 of the following: atopic dermatitis, bronchial asthma, food allergy, allergic rhinitis, and allergic conjunctivitis) as determined by a physician, which was considered a high risk factor for developing food allergy.7,35 Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) neonates younger than 37 weeks of gestational age, (2) neonates with a birth weight less than 2300 g, (3) neonates with birth asphyxia (Apgar score <3 points at 5 minutes), (4) neonates who needed to be admitted to the newborn intensive care unit, (5) neonates who were unable to tolerate breast milk at all after the age of 2 days without specifying whether the route was by breast or bottle, and (6) neonates whose mothers were diagnosed with EA by a physician and could not consume eggs.

Randomization and Grouping

Allocation was performed anonymously using the envelope method, and each facility randomized allocation adjustment factors using the substitution block method. Physicians who followed up the children and evaluated their food allergies were blinded to the randomization results.

Mothers and their neonates were randomized (1:1 ratio) into an MEC group, wherein the mother consumed 1 whole egg per day between 0 and 5 days after delivery, and a maternal egg elimination (MEE) group, wherein the mother eliminated eggs from her diet between 0 and 5 days after delivery.

Treatment Procedures

The eggs consumed by mothers in the MEC group were boiled whole eggs prepared by the nutrition department of each medical facility. The mothers in the MEC group consumed 1 cooked egg per day in addition to their normal breakfast from days 0 to 5, whereas those in the MEE group received a hospital diet that eliminated eggs from days 0 to 5. In Japan, the normal postpartum hospital stay is 5 days. No dietary restrictions were imposed on either group after discharge. After 1 month, both groups were instructed to perform skin care, and aggressive topical corticosteroid treatment was administered for eczema. The treatment procedures and measurements are shown in eFigure 1 in Supplement 2. At age 4 and 12 months, the children’s blood was assessed for egg sensitization. If the egg white– or ovomucoid (OVM)-specific immunoglobulin (Ig)E (sIgE) level was 0.1 allergen-specific kilo units per liter (kUA/L) or more, an oral food challenge (OFC) was performed to assess EA. For the OFC, the total challenge dose was administered in a stepwise manner (250, 775, 3100, and 6200 mg of egg protein) based on the Japanese guidelines for food allergy.7,36,37,38 A positive OFC result was defined by a blinded physician as the appearance of objective or prolonged subjective symptoms. Details of the OFC methods have been previously described.22,36,37,38,39

Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was EA at 12 months, defined as both a positive sensitization to egg white or OVM sIgE greater than or equal to 0.1 kUA/L and a positive test result of OFC or an episode of obvious immediate symptoms after egg ingestion. When the infants were aged 12 months, blinded physicians evaluated the presence or absence of EA. The secondary outcomes were egg protein concentrations in breast milk collected on days 3 to 4 and at age 1 month; sensitization to egg, milk, and wheat; food protein–induced enterocolitis syndrome due to egg, milk, and wheat; and eczema.

Blood tests were performed at age 4 and 12 months to measure total IgE and egg white, OVM, cow’s milk, casein, wheat, and ω-5 gliadin sIgE (ImmunoCAP; Thermo Fisher Scientific/Phadia AB), and an sIgE antibody titer of 0.10 kUA/L or higher was considered sensitization. To measure ovalbumin (OVA) and OVM content in breast milk, on the third or fourth day after delivery, 1 mL of breast milk was collected 3 times in total (1, 3, and 6 hours after breakfast). Concentrations of OVA and OVM in breast milk were determined at the University of Tokushima, using a fluorescently labeled secondary antibody after the anti-OVA or OVM rabbit polyclonal IgG antibody was loaded on the chip and reacted with breast milk stock solution.40,41 The detection sensitivity of OVA was greater than or equal to 0.20 ng/mL and the detection sensitivity of OVM was greater than or equal to 0.78 ng/mL Details of the measurement method are described in the eMethods in Supplement 2.

Statistical Analysis

Infants who were not evaluated for EA at 12 months were excluded. Participants who did not adhere to the intervention were evaluated based on their allocation group. Comparisons between groups were performed using the Fisher exact test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables. Data requiring a distribution of normality were not analyzed. Effects of intervention, such as maternal intake of eggs at birth, were calculated using RRs with 95% CIs, using the Fisher exact test for incidence of food allergy, eczema, and sensitization.

Statistical significance was set at P < .05. All data were processed and summarized using SPSS, version 25.0 (IBM Corp).

Sample Size

Since only neonates at a high risk of developing food allergies were included in this study,35 the EA at 12 months in the MEE group was assumed to be 15%. The preventive effect of early intervention was assumed to be 67%, and that of EA in the MEC group was assumed to be 5%. At a power level of 0.8, assuming loss to follow-up of 20% and considering the differences between centers for conducting this study at 10 facilities throughout Japan, the total number of participants required was 380.

Post Hoc Analysis

The characteristics of infants who developed (EA group) or did not develop (non-EA group) EA were assessed. Clinical factors associated with the development of EA, such as atopic disease, eczema, and intervention of egg ingestion, were analyzed. The risk ratios (RRs) with 95% CIs comparing the factors influencing EA development are reported based on a logistic regression analysis.

Results

Participants

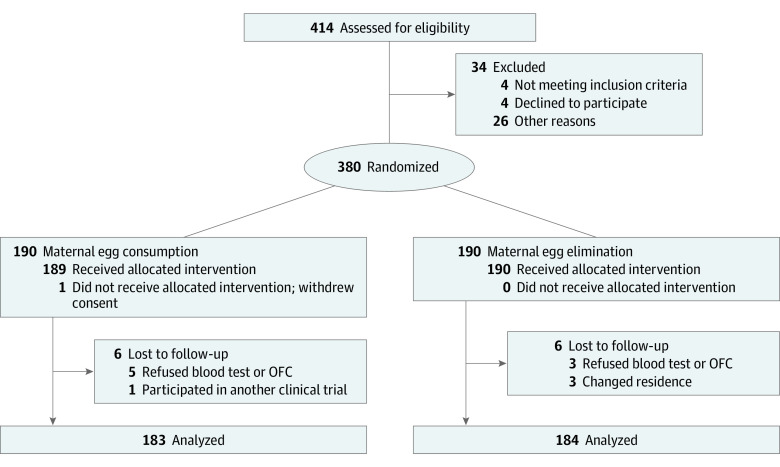

Of 414 included infants, 34 were excluded according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the remaining 380 were enrolled in the RCT (198 females [52.1%] and 182 males [47.9%]): 190 in the MEC group and 190 in the MEE group. Additionally, 13 voluntarily withdrew or were lost to follow-up. A total of 183 infants (96.3%) in the MEC group and 184 infants (96.8%) in the MEE group completed follow-up at age 12 months and were included in the analysis. The follow-up rate for all infants was 96.6% (Figure 1). Table 1 reports the baseline characteristics of all enrolled participants.

Figure 1. Participant Recruitment Flow.

OFC indicates oral food challenge.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Participants in the MEC and MEE Groups.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| MEC group (n = 190) | MEE group (n = 190) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 90 (47.4) | 92 (48.4) |

| Female | 100 (52.6) | 98 (51.6) |

| Gestational age, median (IQR), wk | 39 (38-40) | 39 (38-40) |

| Body weight, median (IQR), g | 3085 (2823.5-3263) | 3000 (2820-3275) |

| Current disease of mother | ||

| Allergic disease | 155 (81.6) | 157 (82.6) |

| Food allergy | 32 (16.8) | 42 (22.1) |

| Current disease of father | ||

| Allergic disease | 156 (82.1) | 150 (78.9) |

| Food allergy | 20 (10.5) | 19 (10.0) |

| No. of siblings | ||

| 0 | 120 (63.2) | 108 (56.8) |

| 1 | 47 (24.7) | 56 (29.5) |

| 2 | 21 (11.1) | 22 (11.6) |

| 3 | 1 (0.5) | 2 (1.1) |

| ≥4 | 1 (0.5) | 2 (1.1) |

| Cesarean delivery | 42 (22.1) | 47 (24.7) |

Abbreviations: MEC, maternal egg consumption; MEE, maternal egg elimination.

Adherence to Intervention and Nutrition Intake Status

During 0 to 5 days of neonatal age, the mothers of 187 neonates (98.4%) in the MEC group ingested a whole egg, whereas the mothers of 184 neonates (96.8%) in the MEE group eliminated eggs from their diets. The adherence rate for all mothers was 97.6%. On day 3, the median amount of breast milk consumed per feed was 12 mL for both groups (eTable 1 in Supplement 2).

At ages 1, 4, 7, and 10 months, the infants’ nutritional methods (ie, exclusively breast milk, mixed feeding, formula intake, and maternal egg intake) did not differ significantly between the MEC and MEE groups (eTable 2 and eTable 3 in Supplement 2).

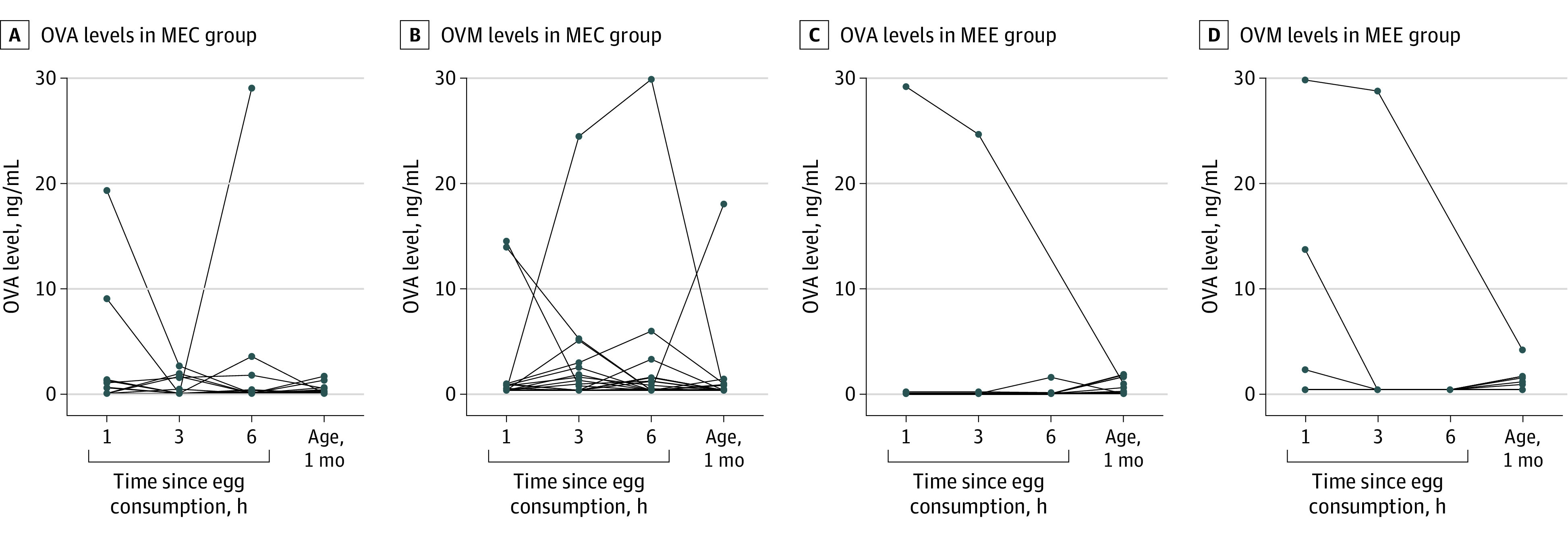

Ovalbumin and Ovomucoid Levels in Breast Milk

On days 3 to 4, the proportions of neonates with OVA and OVM detected in their mothers’ breast milk were higher in the MEC group than in the MEE group (OVA: 10.7% vs 2.0%; RR, 5.23; 95% CI, 1.56-17.56; OVM: 11.3% vs 2.0%; RR, 5.55; 95% CI, 1.66-18.55) (eTable 4 in Supplement 2). Additionally, peak levels of OVA (P = .004) and OVM and OVM in breast milk at 3 and 6 hours after egg consumption were significantly higher in the MEC group than in the MEE group (Figure 2). However, at age 1 month, the OVA and OVM levels in breast milk were not significantly different between the MEC and MEE groups.

Figure 2. Ovalbumin (OVA) and Ovomucoid (OVM) Levels in Breast Milk After Ingestion of a Whole Egg or During the Elimination of Eggs.

A, OVA levels in the maternal egg consumption (MEC) group. B, OVM levels in the MEC group. C, OVA levels in the maternal egg elimination (MEE) group. D, OVM levels in the MEE group. The midwife assisted and collected breast milk at a time when the mother was not feeding.

EA and Other Outcomes

The effects of MEC at birth on EA at 12 months of age (primary outcome) and other secondary outcomes are provided in Table 2. Egg allergy was not significantly different between the MEC and MEE groups (9.3% vs 7.6%; RR, 1.22; 95% CI, 0.62-2.40) (Table 2); the overall EA prevalence was 8.4%. Additionally, the eczema, milk, and wheat allergies at age 1 and 4 months did not differ significantly between groups. Food protein–induced enterocolitis syndrome due to eggs was observed in 1 infant in each group. The sensitization to egg white was 30.1% at age 4 months and 62.8% at age 12 months in the MEC group and 26.6% at age 4 months and 58.7% at age 12 months in the MEE group (MEC vs MEE: 4 months: RR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.81-1.56; 12 months: RR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.91-1.26). The overall sensitization to egg at 12 months was 60.7%. Moreover, sensitization to milk and wheat did not differ significantly between the 2 groups (Table 2; eFigure 2 in Supplement 2). An interim analysis was performed when the primary outcome was achieved for every 100 infants, and all analyses exceeded the Peto cutoff of 0.001, and this study continued.

Table 2. Prevalence of Eczema at Age 1 and 4 Months and Food Allergy and Sensitization at Age 12 Months.

| Outcome | No. (%) | RR (95% CI)a | P valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEC group (n = 183) | MEE group (n = 184) | |||

| At 1 mo assessment | ||||

| Eczema | 71 (38.8) | 72 (39.1) | 0.99 (0.77-1.28) | >.99 |

| At 4 mo assessment | ||||

| Eczema | 64 (35.0) | 67 (36.4) | 0.96 (0.73-1.26) | .83 |

| Sensitization to egg | 55 (30.1) | 49 (26.6) | 1.13 (0.81-1.56) | .49 |

| Sensitization to milk | 30 (16.4) | 34 (18.5) | 0.89 (0.57-1.39) | .68 |

| Sensitization to wheat | 8 (4.4) | 11 (6.0) | 0.73 (0.30-1.78) | .64 |

| At 12 mo assessment | ||||

| IgE-mediated egg allergy | 17 (9.3) | 14 (7.6) | 1.22 (0.62-2.40) | .58 |

| IgE-mediated milk allergy | 3 (1.6) | 3 (1.6) | 1.01 (0.21-4.92) | >.99 |

| IgE-mediated wheat allergy | 2 (1.1) | 0 | NA | NA |

| Sensitization to egg | 115 (62.8) | 108 (58.7) | 1.07 (0.91-1.26) | .46 |

| Sensitization to milk | 68 (37.2) | 73 (39.7) | 0.94 (0.72-1.21) | .67 |

| Sensitization to wheat | 47 (25.7) | 46 (25.0) | 1.03 (0.72-1.46) | .91 |

| FPIES due to egg | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 1.01 (0.06-15.95) | >.99 |

Abbreviations: FPIES, food protein–induced enterocolitis syndrome; MEC, maternal egg consumption; MEE, maternal egg elimination; NA, not applicable; RR, risk ratio.

Estimated as the risk of the effects of intervention (ie, maternal intake of eggs at birth) on outcomes.

To clarify whether the intervention significantly affected the outcomes, P values were analyzed using the Fisher exact test.

Adverse Events

No adverse events were observed in either group during the intervention period (days 0-5). Regarding serious adverse events during the entire study period up to 12 months, 1 patient in the MEE group was hospitalized because of a urinary tract infection at age 9 months.

Post Hoc Analysis

Between the EA and non-EA groups, statistical significance was observed for cesarean delivery, OVM detection in breast milk on days 3 and 4, and eczema at 1 month (Table 3). Logistic regression analysis revealed that OVM detection in breast milk on days 3 and 4 (adjusted RR [ARR], 4.04; 95% CI, 1.58-10.32) and eczema at 1 month (ARR, 2.85; 95% CI, 1.39-5.85) were significant risk factors for developing EA (eTable 5 in Supplement 2).

Table 3. Comparison of Characteristics Between Children Who Developed Egg Allergy and Those Who Did Not Develop Egg Allergy.

| Variable | No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Egg allergy (n = 31) | No egg allergy (n = 336) | ||

| At birth | |||

| Sex | |||

| Male | 17 (54.8) | 157 (46.7) | .40 |

| Female | 14 (45.2) | 179 (53.3) | |

| No. of siblings | |||

| 0 | 21 (67.7) | 200 (59.5) | .37 |

| 1 | 8 (25.8) | 91 (27.1) | |

| 2 | 1 (3.2) | 40 (11.9) | |

| 3 | 1 (3.2) | 2 (0.6) | |

| ≥4 | 0 | 3 (0.9) | |

| Father with allergic diseases | 26 (83.9) | 274 (81.5) | .75 |

| Father with FA | 3 (9.7) | 36 (10.7) | .86 |

| Mother with allergic diseases | 29 (93.5) | 271 (80.7) | .08 |

| Mother with FA | 8 (25.8) | 61 (18.2) | .30 |

| Cesarean delivery | 12 (38.7) | 75 (22.3) | .04 |

| During hospitalization | |||

| Intervention of egg ingestion based on RCT | 17 (54.8) | 166 (49.4) | .56 |

| Formula protein ingestion during days 0-3 | 16/20 (80.0) | 166/212 (78.3) | >.99 |

| OVA detection in breast milk on days 3-4 | 3/23 (13.0) | 16/274 (5.8) | .18 |

| OVM detection in breast milk on days 3-4 | 4/23 (17.4) | 17/274 (6.2) | .03 |

| At 1 mo | |||

| Eczema | 20 (64.5) | 123 (36.6) | .006 |

| Complete breastfeeding | 10 (32.3) | 104 (31.0) | .83 |

| Frequency of mothers’ egg consumption, median, times/wk (IQR) | 5 (5-7) | 5 (2-7) | .87 |

| Amount of mothers’ egg consumption, median, No. (IQR) | 1 (1-1) | 1 (1-1) | .73 |

| OVA detection in breast milk | 1/24 (4.2) | 17/269 (6.3) | .68 |

| OVM detection in breast milk | 0/24 | 12/269 (4.5) | >.99 |

Abbreviations: FA, food allergy; OVA, ovalbumin; OVM, ovomucoid; RCT, randomized clinical trial.

In the MEC group, the EA at 12 months was 50.0% in infants who had detectable OVM levels and developed eczema, 13.3% in those who had detectable OVM levels and did not develop eczema, 10.3% in those who had undetectable OVM levels and developed eczema, and 4.2% in those who had undetectable OVM levels and did not develop eczema. In the MEE group, no infants fulfilled both risk factors, and the EA was 33.3% in infants who had detectable OVM levels and did not develop eczema, 12.5% in those who had undetectable OVM levels and developed eczema, and 2.5% in those who had undetectable OVM levels and did not develop eczema (eFigure 3 in Supplement 2).

Discussion

This multicenter RCT with high adherence (97.6%) and follow-up rates (96.6%) determined the effect of maternal egg intake during the early neonatal period (0-5 days) on the development of EA in infants aged 12 months. The proportion of neonates aged 3 to 4 days with OVA and OVM detected in their mothers’ breast milk was higher in the MEC group than in the MEE group. However, EA at age 12 months was not significantly different between the MEC and MEE groups (9.3% vs 7.6%).

At the time of designing the current study, we hypothesized that egg consumption via breast milk in the early neonatal period prevented the development of EA, just as in the case of egg consumption in infancy.14,15,16 However, EA did not differ significantly between the MEC and MEE groups. There are 2 possible reasons for this. First, the intervention amount was relatively low and intervention period was relatively short. In previous trials attempting to prevent the development of EA, infants consumed gram units of egg protein for 3 to 6 months.14,15,16,24,25,26 However, in the current RCT, infants consumed very small amounts of egg protein (micrograms) for only 5 days. It is possible that the ingestion of larger amounts of egg protein and a longer intervention period, such as during pregnancy or after the neonatal period, might lead to different results. The second reason is the difference in the timing of egg ingestion. The gut environment, including the microbiome, changes dynamically during the neonatal period and early infancy.42 The current study did not evaluate the microbiome or the mother’s antibiotic use; further trials are required.

Egg allergy and sensitization to eggs tended to be higher in the MEC group, contrary to our original hypothesis. Consistently, a few studies suggested that neonatal exposure to food protein would promote the development of food allergy, unlike exposure in middle and late infancy.29,30,31,43 For example, in the BENEFIT (Breastfeeding and Eating Nuts and Eggs for Infant Tolerance) pilot trial, mothers were randomized to consume 6 or more eggs per week (high egg group) or 2 or fewer eggs per week (low egg group) from the neonate’s birth to age 6 months; the prevalence of EA at age 12 months was higher in the high egg group (10.0%) than in the low egg group (0.0%).43 Additionally, regarding milk allergy, 2 cohort trials and 1 RCT reported that early neonatal formula protein intake increased the subsequent development of milk allergy.29,30,31 These previous findings are similar to those observed in the present study, demonstrating that egg intake via breast milk in the early neonatal period might promote EA.

In the MEC group, the proportion of neonates with OVA and OVM detection in breast milk on days 3 and 4 was only 10.7%, which was lower than originally expected. In some previous trials, OVA was detected in mature milk in approximately 50% of infants 1 to 6 hours after their mothers ingested eggs.32,33,34 When designing the present study, we analyzed OVA and OVM levels in mature milk using our assay method and found that OVA and OVM were detected in 2 of the 4 cases (50%). Moreover, the detection sensitivity of OVA with our assay method was 0.20 ng/mL or greater, whereas that in previous studies was 0.57 ng/mL or greater,32,34 indicating our assay method is reliable. There may be differences in egg protein secretion between the colostrum and mature milk. The reason why OVA and OVM were detected in 2% of the MEE group may be due to contamination or egg consumption during pregnancy; however, in the present study, egg consumption during pregnancy has not been investigated. These issues should be assessed in future studies.

The post hoc analysis identified eczema at 1 month as a risk factor for EA development. Several cohort studies have consistently reported that eczema in early infancy is a risk factor for the subsequent development of EA.44,45,46,47 Furthermore, the current trial demonstrated that detecting OVM in breast milk in the early neonatal period was also a risk factor for EA. However, an Australian cohort study noted that infants with OVA detected in their mothers’ breast milk at age 3 and 6 months had a lower prevalence of EA than those without OVA detection.33,48 Although OVA and OVM in breast milk were not measured at birth in Australian cohort studies,33,47 as well as at 3 and 6 months in this trial, we hypothesized that the conflicting results might be due to a difference in the timing of exposure to egg protein. Notably, 2 RCTs on milk allergy also showed conflicting results: milk protein intake in the early neonatal period (age 0-3 days) promoted the development of milk allergy, whereas milk protein intake in early infancy (age 1-2 months) suppressed the development of milk allergy.29,49,50 Similarly, with regard to egg protein intake via breast milk, the effect on the subsequent development of EA may vary depending on the time of year.

Limitations

This trial has some limitations. First, the overall prevalence of EA was 8.4%, lower than the initially expected 15%. The reason for the low prevalence of EA was speculated to be strict skin care and aggressive topical corticosteroid therapy starting at age 1 month. Aggressive topical corticosteroid therapy in infants with eczema may decrease the incidence of food allergies.51,52 The positive sensitization rate was 60.7%, suggesting that low sIgE levels had little clinical relevance. Therefore, the number of participants might be insufficient to examine the hypotheses of the current trial. Second, EA was diagnosed using an open OFC rather than double-blind food challenges. However, the OFC evaluators were blinded to whether infants were assigned to the MEC or MEE group. Additionally, because the OFC participants were infants, few cases presented subjective symptoms. Therefore, the effect of the open method was minimal.

Conclusions

In this RCT, the development of EA and sensitization to egg whites was unaffected by MEC during the early neonatal period. No adverse effects were observed with either intervention.

Trial Protocol

eFigure 1. Intervention Procedures

eFigure 2. Specific IgE Levels at 4 and 12 Months of Age

eFigure 3. Prevalence of Immediate-Type Egg Allergy Based on the OVM Detection in Breast Milk on Days 3-4 and Eczema at 1 Month in Both Groups

eTable 1. Adherence to Intervention During Admission

eTable 2. Nutrition Methods at 1 and 4 Months of Age

eTable 3. Nutrition Methods in Children at 7 and 10 Months of Age

eTable 4. Proportions of Infants With OVA and OVM Detection in Breast Milk

eTable 5. Logistic Regression Analysis of Factors Contributing to Developing IgE-Mediated Egg Allergy

eMethods. Determination of OVA and OVM Antigen Levels in Breast Milk Using a DCP Chip Equipped With Antigen-Specific Antibodies

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Sicherer SH, Sampson HA. Food allergy: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(2):291-307. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanno LK, Demoly P. Food allergy in the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-11. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2022;33(11):e13882. doi: 10.1111/pai.13882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sicherer SH, Muñoz-Furlong A, Godbold JH, Sampson HA. US prevalence of self-reported peanut, tree nut, and sesame allergy: 11-year follow-up. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(6):1322-1326. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.03.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hossny E, Ebisawa M, El-Gamal Y, et al. Challenges of managing food allergy in the developing world. World Allergy Organ J. 2019;12(11):100089. doi: 10.1016/j.waojou.2019.100089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sicherer SH, Sampson HA. Food allergy: a review and update on epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, prevention, and management. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(1):41-58. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halken S, Muraro A, de Silva D, et al. ; European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Guidelines Group . EAACI guideline: preventing the development of food allergy in infants and young children (2020 update). Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2021;32(5):843-858. doi: 10.1111/pai.13496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ebisawa M, Ito K, Fujisawa T; Committee for Japanese Pediatric Guideline for Food Allergy, The Japanese Society of Pediatric Allergy and Clinical Immunology; Japanese Society of Allergology . Japanese guidelines for food allergy 2020. Allergol Int. 2020;69(3):370-386. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2020.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peters RL, Allen KJ, Dharmage SC, et al. ; HealthNuts Study . Skin prick test responses and allergen-specific IgE levels as predictors of peanut, egg, and sesame allergy in infants. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(4):874-880. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.05.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan JW, Joshi P. Egg allergy: an update. J Paediatr Child Health. 2014;50(1):11-15. doi: 10.1111/jpc.12408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagakura KI, Sato S, Asaumi T, Yanagida N, Ebisawa M. Novel insights regarding anaphylaxis in children—with a focus on prevalence, diagnosis, and treatment. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2020;31(8):879-888. doi: 10.1111/pai.13307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samady W, Warren C, Wang J, Das R, Gupta RS. Egg allergy in US children. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(9):3066-3073.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.04.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.du Toit G, Tsakok T, Lack S, Lack G. Prevention of food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(4):998-1010. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krawiec M, Fisher HR, Du Toit G, Bahnson HT, Lack G. Overview of oral tolerance induction for prevention of food allergy—where are we now? Allergy. 2021;76(9):2684-2698. doi: 10.1111/all.14758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perkin MR, Logan K, Tseng A, et al. ; EAT Study Team . Randomized trial of introduction of allergenic foods in breastfed infants. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(18):1733-1743. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1514210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Natsume O, Kabashima S, Nakazato J, et al. ; PETIT Study Team . Two-step egg introduction for prevention of egg allergy in high-risk infants with eczema (PETIT): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10066):276-286. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31418-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishimura T, Fukazawa M, Fukuoka K, et al. Early introduction of very small amounts of multiple foods to infants: a randomized trial. Allergol Int. 2022;71(3):345-353. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2022.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burks AW, Jones SM, Wood RA, et al. ; Consortium of Food Allergy Research (CoFAR) . Oral immunotherapy for treatment of egg allergy in children. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(3):233-243. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caminiti L, Pajno GB, Crisafulli G, et al. Oral immunotherapy for egg allergy: a double-blind placebo-controlled study, with postdesensitization follow-up. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015;3(4):532-539. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2015.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yanagida N, Sato S, Asaumi T, Nagakura K, Ogura K, Ebisawa M. Safety and efficacy of low-dose oral immunotherapy for hen’s egg allergy in children. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2016;171(3-4):265-268. doi: 10.1159/000454807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pérez-Rangel I, Rodríguez Del Río P, Escudero C, Sánchez-García S, Sánchez-Hernández JJ, Ibáñez MD. Efficacy and safety of high-dose rush oral immunotherapy in persistent egg allergic children: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;118(3):356-364.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2016.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takaoka Y, Maeta A, Takahashi K, et al. Effectiveness and safety of double-blind, placebo-controlled, low-dose oral immunotherapy with low allergen egg-containing cookies for severe hen’s egg allergy: a single-center analysis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2019;180(4):244-249. doi: 10.1159/000502956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagakura KI, Sato S, Yanagida N, Ebisawa M. Novel immunotherapy and treatment modality for severe food allergies. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;17(3):212-219. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ierodiakonou D, Garcia-Larsen V, Logan A, et al. Timing of allergenic food introduction to the infant diet and risk of allergic or autoimmune disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(11):1181-1192. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.12623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palmer DJ, Metcalfe J, Makrides M, et al. Early regular egg exposure in infants with eczema: a randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(2):387-92.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palmer DJ, Sullivan TR, Gold MS, Prescott SL, Makrides M. Randomized controlled trial of early regular egg intake to prevent egg allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(5):1600-1607.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.06.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bellach J, Schwarz V, Ahrens B, et al. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of hen’s egg consumption for primary prevention in infants. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(5):1591-1599.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.06.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wei-Liang Tan J, Valerio C, Barnes EH, et al. ; Beating Egg Allergy Trial (BEAT) Study Group . A randomized trial of egg introduction from 4 months of age in infants at risk for egg allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(5):1621-1628.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.08.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ikematsu K, Tachimoto H, Sugisaki C, Syukuya A, Ebisawa M. [Feature of food allergy developed during infancy (1)–relationship between infantile atopic dermatitis and food allergy] [Article in Japanese]. Arerugi. 2006;55(2):140-150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Urashima M, Mezawa H, Okuyama M, et al. Primary prevention of cow’s milk sensitization and food allergy by avoiding supplementation with cow’s milk formula at birth: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(12):1137-1145. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.3544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kelly E. DunnGalvin G, Murphy BP, O’B Hourihane J. Formula supplementation remains a risk for cow’s milk allergy in breastfed infants. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2019;30(8):810-816. doi: 10.1111/pai.13108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Høst A, Husby S, Osterballe O. A prospective study of cow’s milk allergy in exclusively breast-fed infants: incidence, pathogenetic role of early inadvertent exposure to cow’s milk formula, and characterization of bovine milk protein in human milk. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1988;77(5):663-670. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1988.tb10727.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Metcalfe JR, Marsh JA, D’Vaz N, et al. Effects of maternal dietary egg intake during early lactation on human milk ovalbumin concentration: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Exp Allergy. 2016;46(12):1605-1613. doi: 10.1111/cea.12806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rekima A, Bonnart C, Macchiaverni P, et al. A role for early oral exposure to house dust mite allergens through breast milk in IgE-mediated food allergy susceptibility. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(5):1416-1429.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.12.912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palmer DJ, Gold MS, Makrides M. Effect of cooked and raw egg consumption on ovalbumin content of human milk: a randomized, double-blind, cross-over trial. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35(2):173-178. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02170.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muraro A, Halken S, Arshad SH, et al. ; EAACI Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Guidelines Group . EAACI food allergy and anaphylaxis guidelines: primary prevention of food allergy. Allergy. 2014;69(5):590-601. doi: 10.1111/all.12398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yanagida N, Sato S, Takahashi K, et al. Stepwise single-dose oral egg challenge: a multicenter prospective study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(2):716-718.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nagakura KI, Yanagida N, Sato S, Ogura K, Ebisawa M. Acquisition of tolerance to egg allergy in a child with repeated egg-induced acute pancreatitis. Allergol Int. 2018;67(4):535-537. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2018.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yanagida N, Minoura T, Kitaoka S, Ebisawa M. A three-level stepwise oral food challenge for egg, milk, and wheat allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(2):658-660.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mitomori M, Yanagida N, Nishino M, et al. Threshold and safe ingestion dose among infants sensitized to hen’s egg. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2022;33(7):e13830. doi: 10.1111/pai.13830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kido H, Izumi K, Otsuka H, Fukusen N, Kato Y, Katunuma N. A chymotrypsin-type serine protease in rat basophilic leukemia cells: evidence for its immunologic identity with atypical mast cell protease. J Immunol. 1986;136(3):1061-1065. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.136.3.1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suzuki K, Hiyoshi M, Tada H, et al. Allergen diagnosis microarray with high-density immobilization capacity using diamond-like carbon-coated chips for profiling allergen-specific IgE and other immunoglobulins. Anal Chim Acta. 2011;706(2):321-327. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2011.08.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fazlollahi M, Chun Y, Grishin A, et al. Early-life gut microbiome and egg allergy. Allergy. 2018;73(7):1515-1524. doi: 10.1111/all.13389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Palmer DJ, Silva DT, Prescott SL. Maternal peanut and egg consumption during breastfeeding randomized pilot trial. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2022;33(9):e13845. doi: 10.1111/pai.13845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martin PE, Eckert JK, Koplin JJ, et al. ; HealthNuts Study Investigators . Which infants with eczema are at risk of food allergy? results from a population-based cohort. Clin Exp Allergy. 2015;45(1):255-264. doi: 10.1111/cea.12406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shoda T, Futamura M, Yang L, et al. Timing of eczema onset and risk of food allergy at 3 years of age: a hospital-based prospective birth cohort study. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;84(2):144-148. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2016.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kalb B, Marenholz I, Jeanrenaud ACSN, et al. Filaggrin loss-of-function mutations are associated with persistence of egg and milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;150(5):1125-1134. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2022.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grimshaw KEC, Roberts G, Selby A, et al. Risk factors for hen’s egg allergy in Europe: EuroPrevall birth cohort. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(4):1341-1348.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.11.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verhasselt V, Genuneit J, Metcalfe JR, et al. Ovalbumin in breastmilk is associated with a decreased risk of IgE-mediated egg allergy in children. Allergy. 2020;75(6):1463-1466. doi: 10.1111/all.14142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sakihara T, Otsuji K, Arakaki Y, Hamada K, Sugiura S, Ito K. Randomized trial of early infant formula introduction to prevent cow’s milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147(1):224-232.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sakihara T, Otsuji K, Arakaki Y, Hamada K, Sugiura S, Ito K. Early discontinuation of cow’s milk protein ingestion is associated with the development of cow’s milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10(1):172-179. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.07.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miyaji Y, Yang L, Yamamoto-Hanada K, Narita M, Saito H, Ohya Y. Earlier aggressive treatment to shorten the duration of eczema in infants resulted in fewer food allergies at 2 years of age. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(5):1721-1724.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.11.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamamoto-Hanada K, Kobayashi T, Williams HC, et al. Early aggressive intervention for infantile atopic dermatitis to prevent development of food allergy: a multicenter, investigator-blinded, randomized, parallel group controlled trial (PACI Study)—protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Clin Transl Allergy. 2018;8:47. doi: 10.1186/s13601-018-0233-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eFigure 1. Intervention Procedures

eFigure 2. Specific IgE Levels at 4 and 12 Months of Age

eFigure 3. Prevalence of Immediate-Type Egg Allergy Based on the OVM Detection in Breast Milk on Days 3-4 and Eczema at 1 Month in Both Groups

eTable 1. Adherence to Intervention During Admission

eTable 2. Nutrition Methods at 1 and 4 Months of Age

eTable 3. Nutrition Methods in Children at 7 and 10 Months of Age

eTable 4. Proportions of Infants With OVA and OVM Detection in Breast Milk

eTable 5. Logistic Regression Analysis of Factors Contributing to Developing IgE-Mediated Egg Allergy

eMethods. Determination of OVA and OVM Antigen Levels in Breast Milk Using a DCP Chip Equipped With Antigen-Specific Antibodies

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement