Abstract

During the analysis of benziamidazole-class irreversible proton pump inhibitors, an unusual mass spectral response with the mass-to-charge ratio at [M+10]+ intrigued us, as it couldn't be assigned to any literature known relevant structure, intermediate or adduct ion. Moreover, this mysterious mass pattern of [M+10]+ has been gradually observed by series of marketed proton pump inhibitors, viz. omeprazole, pantoprazole, lansoprazole and rabeprazole. All the previous attempts to isolate the corresponding component were unsuccessful. The investigation of present work addresses this kind of signal to a pyridinium thiocyanate mass spectral intermediate (10), which is the common fragment ion of series of labile aggregates. The origin of such aggregates can be traced to the reactive intermediates formed by acid-promoted degradation. These reactive intermediates tend to react with each other and give raise series of complicated aggregates systematically in a water/acetonitrile solution by electrospray ionization. The structure of the corresponding pyridinium thiocyanate species of omeprazole (10a) has been eventually characterized with the help of synthetic specimen (10a′). Our structural proposal as well as its origin was supported by in situ nuclear magnetic resonance, chemical derivatization and colorimetric experiments.

Keywords: Proton pump inhibitor, Mass spectrometry, Electrospray ionization, Pseudo-molecular ion, Pyridinium thiocyanate

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

A common MS-intermediate among benziamidazole-class PPIs has been identified.

-

•

Structure of the corresponding pyridinium thiocyanate intermediate has been characterized.

-

•

Origin of such pseudo related substance has been investigated by a variety of methods.

1. Introduction

The irreversible proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) of the benziamidazole-class are group of acid-sensitive prodrugs, which have been proved to be effective at suppressing gastric acid secretion by binding to the cysteines of the H+/K+-ATPase covalently. The pharmacophores of PPIs are pyridyl, methylsulfinyl and benzimidazole, which connect to each other as in timoprazole. This basic structural framework has been maintained through the development of PPIs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Frameworks of the marketed irreversible proton pump inhibitors (PPIs, 1).

|

R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omeprazole (1a)/Esomeprazole | 1988 SE 2000 GB | MeO− | Me− | MeO− | Me− |

| Pantoprazole (1b) | 1994 DE | CF2HO− | MeO− | MeO− | H− |

| Lansoprazole (1c)/Dexlansoprazole | 1991 FR 2009 US | H− | Me− | CF3CH2O− | H− |

| Rabeprazole (1d) | 1997 JP | H− | Me− | MeO(CH2)3O− | H− |

| Ilaprazole (1e) | 2008 CN | 1-Pyrrolyl− | Me− | MeO− | H− |

| Leminorazole (1f) | 2010 JP | MeO− | Me2N− | H− | H− |

The two base moieties in the molecule endow PPIs with two pKas and therefore PPIs are to be activated first through doubled protonation processes (Fig. 1). The secondary protonation on the benzimidazole triggers an intramolecular rearrangement, namely Truce-Smiles rearrangement [1,2]. Through a spiro intermediate, a pyridinium sulfenic acid (2) will be formed. This active species can either react directly or via a cyclic pyridinium sulfenamide intermediate (3) with the cysteine and form a disulfide adduct (4) [3,4]. The covalent binding on the Cys321, Cys813 and Cys822 within the proton pumps as to on the Cys892 outside the proton pumps will eventually block the proton pump [5,6]. The substituents on the pyridine and benzimidazole rings may have a certain impact on the activation of the PPIs. All the irreversible PPIs are pharmacologically acid-sensitive. Due to the acid-labile character of PPIs, the corresponding protolytic substance is a matter of concern in pharmaceutical production [7].

Fig. 1.

Mechanism of acid activation of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) [1].

Recently, a feeble signal with mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) at 355.1227 in the samples of omeprazole (1a) aroused our attention (Fig. S1A). Considering the protonic adduct ion of omeprazole [M+H]+ is to be found at m/z 346.12, [M+10]+ appears not to be an common adduct ion of ammonium or alkali metals. A reasonable molecular formula fitting to m/z 355.12 is [M−O+C+N]+ at m/z 355.1223. The degree of unsaturation of this molecular formula reminds us of a cyanide group (−CN). According to the best of our knowledge, no cyanide containing related substance or intermediate in PPIs has been reported. The corresponding component has been subsequently isolated via preparative liquid chromatography (LC). Interestingly, the mass spectral response of [M+10]+ was just minority in the residue after evaporating the solvent. It seems that the related substance was labile. All the attempts of isolation and characterization of this species remained unsuccessful. In the present study, quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (Q-TOF MS), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analytical methods combined with solid phase extraction (SPE) separation technique, chemical derivatization and colorimetric strategies were applied for investigating this phenomenon. A pyridinium thiocyanate species, a common fragment ion derived from hydrolyzed PPIs, has been identified and the origin of such species has been discussed.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

PPIs (Omeprazole, pantoprazole, lansoprazole and rabeprazole), derivatization reagents (cysteamine, 5,5-dimethyl-1,3-cyclohexanedione), pyridyl and benzimidazole building blocks (2-(chloromethyl)-3-methyl-4-(2,2,2-trifluoroethoxy)pyridine hydrochloride, 5-methoxy-2-thio-1H-benzimidazole, 5-(difluoromethoxy)-2-mercapto-1H-benzimidazole) of analytical grade were purchased from Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-grade acetonitrile and methanol were from Fisher Scientific Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All other reagents and solvents were of analytical grade.

2.2. MS

MS was performed on a triple TOF 5600 and 6600 mass spectrometer (SCIEX, Toronto, Canada), each equipped with a TurboIonSpray™ ESI source. Data acquisition was achieved using Analyst software 1.6.1 and 1.5.2. In fragmentation experiments, analyte solutions were diluted thousand times with diluents and infused into the MS through a syringe pump at 10 μL/min. Optimized MS parameters were as follows: Source temperature, 500 °C; ion spray voltage, 5500 V; nebulizer, heater, and curtain gas (N2), 50, 50, 20 psi, respectively. Declustering potential (DP), collision energy (CE), and air flow (AF2) values were tuned manually in each experiment.

2.3. Degradation and derivatization protocol

To a solution of 1 mg/mL PPI (water/acetonitrile, 4/1), 1 μL formic acid was added and the mixture was incubated for 30 min at ambient temperature. Obvious color change from pale yellow to dark brown could be observed by the samples of omeprazole, lansoprazole and ilaprazole. For derivatization reactions, an acetonitrile solution of 1 mg/mL corresponding derivatization reagent (cysteamine, 5,5-dimethyl-1,3-cyclohexanedione) was added to the aforementioned degradation solution and incubated for 15 min at ambient temperature.

2.4. SPE purification and NMR

Pre-condition of the SPE cartridges (Agilent Bond Elut™ C18, 500 mg, 3 mL; Folsom, CA, USA): flush the SPE cartridges sequentially with 2 mL acetonitrile (1 mL each time) and 2 mL water (1 mL each time), and excess solvent was removed under vacuum. Load the degradation sample to the pre-conditioned SPE cartridge and wash the cartridge with 2 mL water (1 mL each time), and excess solvent was removed under vacuum. Elute the loaded SPE cartridge with 1 mL d4-methanol for the direct NMR experiments. The 1D and 2D NMR experiments were performed on Bruker™ 400 MHz and 600 MHz spectrometer (Billerica, MA, USA).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. MS responses of [M+10]+ among the PPIs

The species of m/z 355.12 should be a relevant substance of omeprazole (1a), since a benzimidazole product ion at m/z 149.07 can be found in the multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) experiment (Fig. S1B). At the beginning, the MS response at m/z 355.12 could be only occasionally observed. Investigations indicate water/acetonitrile mixed solvent and low pH value favor the transformation from [M+H]+ to [M+10]+. Moreover, this phenomenon could be reproduced by series of PPIs (Fig. S2).

3.2. Solvent effect and solvent adducts

Considering the acid-labile character of PPIs, the [M+10]+ species is presumably related with the acid-promoted degradation reaction. The protonolysis experiments with omeprazole (1a) have been conducted in two kinds of mixed solvent systems respectively, viz. water/methanol and water/acetonitrile. The protolytic samples were then diluted 100 times and analyzed through syringe pump. A signal of the [M+10]+ kind for 1a at m/z 355.12 can be only obviously observed in water/acetonitrile diluents, regardless which kind of protolytic solvent has been applied.

Such a solvent specific mass spectral response gives an impression that the signal of [M+10]+ might be an acetonitrile adduct ion [8]. A parallel experiment has been then conducted in water/d3-acetonitrile. If the mass spectral response at m/z 355 was an acetonitrile adduct, a corresponding adduct ion of deuterium acetonitrile should be observed at m/z 358. The relative percentage signal intensity of m/z 355 in d3-acetonitrile (Fig. S3A) is stronger than that in acetonitrile (Fig. S3B), but without the trace of m/z 358. Beyond that, the collision-induced dissociation (CID) of m/z 355.12 produces a fragment at m/z 328.12, which matches the cyclic pyridinium sulfenamide intermediate (3a). It hints that the molecular scaffold of omeprazole remains unchanged and the signal at m/z 355.12 couldn't be an acetonitrile adduct ion.

The hybrid solvent experiment has been then carried out with other PPIs. 1a−d have been first acidolyzed in water/acetonitrile for 40 min at room temperature, followed by dilution 49 times with different diluents (water/methanol, water/ethanol or water/acetone) and analyzed through syringe pump. The MS responses of [M+10]+ were faint in the diluents others than water/acetonitrile, while signals of 1a−d or thioether 8a−d in the mixture were not significantly affected by the solvent shifting. Moreover, solvent adducts have been observed, especially in water/acetone (Table S1). Since [M+10]+ isn't an acetonitrile adduct but its occurrence is acetonitrile dependent, it is highly likely derived from some labile intermediates.

3.3. SPE enrichment and in situ NMR experiment

In order to prevent the potential decomposition during the separation or solvent evaporation procedure, SPE separation has been employed for the enrichment of the target substance. Washing the loaded SPE column with deuterated solvent, the eluent was directly ready for an NMR test. The 1D/2D NMR and TOF MS experiments point the main component in the eluent to a disulfide dimer 7a, a literature known degradation product. Although the mass spectral response at m/z 355.12 is still to be detected in the eluent, no sign of cyanide could be observed by distortionless enhancement by polarization transfer (DEPT) NMR. Moreover, the color of the sample 7a in NMR tube turned from yellow to black after several days deposing at ambition temperature. Retesting of the sample by NMR and MS indicates the disulfide dimer 7a was transformed into thioether 8a spontaneously and completely [[9], [10], [11], [12], [13]].

According to the previous work [3,14], the disulfide dimer 7a is formed between two reactive intermediates, pyridinium sulfonamide 3a and pyridinium thiole 6a (Fig. 2). The mass spectral response at m/z 355.12 may suggest the participation of some short-life cyanide intermediate during the protonolysis. Consequently, an in situ protonolysis experiment has been conducted in NMR-tube, in order to capture some evidences of such a “transient” intermediate. With the decay of the omeprazole signals within 15 min at room temperature, only a reactive intermediate sulfenic acid 2a has been recorded. There is no newly emerged sp-hybridized carbon signal in the NMR spectrum to be found. Based on the aforementioned observation, we had the assumption that the mass spectral response of [M+10]+ was a product ion of some intermediates instead of intermediates themselves.

Fig. 2.

Literature reported formation of disulfide dimer 7.

3.4. Series of double charged pyridinium salt dimers

It has been found that the signal of [M+10]+ in the protolytic solution of 1 was always accompanied by series of double charged species, such as the disulfide dimer 7a. The double charged species are to be recognized easily by MS from their 0.5 Da mass difference between the isotope signals. For example, the MS response of 7a is to be found at m/z 329.12, its single charged form 7a′ is to be found at m/z 657.23. Beyond that, thiosulfinate intermediate 5a at m/z 337.12 and 673.23 and trisulfide dimer 9a at m/z 345.10 and 689.20 can also be found in the protolytic sample of omeprazole (Fig. 3). It has been noticed later that the pattern of [pyridinium dimer]2+, [pyridinium dimer+O]2+ and [pyridinium dimer+S]2+ can be observed in the protolytic samples across the PPIs (Table S2).

Fig. 3.

Trisulfide dimers 9a and 9a′.

Noteworthy, in the protolytic solution of 1a, there are still series of pyridinium dimers with feeble intensity to be found at m/z 533.65, 536.22, 549.64, 552.20, 557.62, 560.18, etc. Without evidence from a secondary characterization method, the structures of these species remained unrevealed. However, it indicates that the pyridinium intermediates of PPIs tend to aggregate and form some complicated dimers systematically during the protonolysis. Such aggregates are labile under the electrospray ionization (ESI) or CID conditions. The signal of [M+10]+ should be one kind of stable CID fragment ion in common.

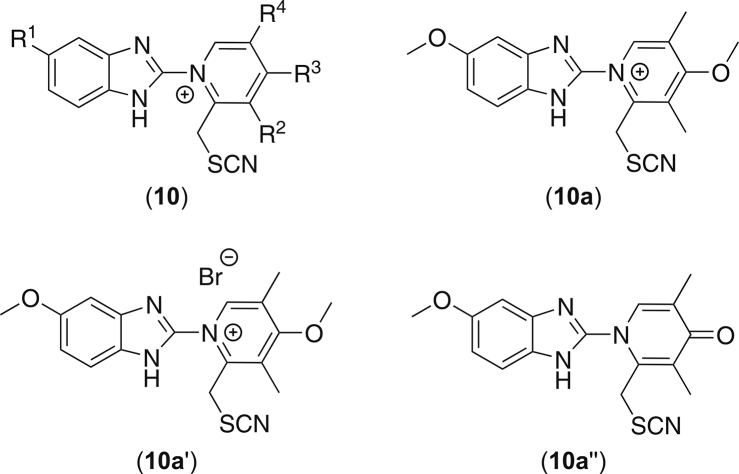

3.5. Structure and mechanism proposal of [M+10]+

All the aforementioned protolytic intermediates of omeprazole observed by NMR and MS contained the segment of 2-pyridiniobenzimidazolide. And the MRM transition of m/z 353.1 → 26.0 and 57.9 under negative mode suggests that this fragment contains a CN- and SCN-moiety (Fig. S1C). Following these structural clues, the pyridinium thiocyanate (10) for the [M+10]+ emerged (Fig. 4). Consequently, the thiocyanate 10a′ in form of bromide salt has been synthesized and investigated (Fig. S4), which exhibits the exactly identical MS2 fragmentation pattern to that of 10a. The structure of 10a′ has been characterized by 1D/2D NMR. The sp-hybrid carbon of the thiocyanate group has been recorded by NMR at 112.5 ppm in CDCl3. Unlike the insubstantial behavior of m/z 355.12 in the previous experiments, the synthesized thiocyanate 10a′ is relatively stable in water/methanol solution at low temperature. These results again confirmed our proposal that the mass spectral response of [M+10]+ is an MS fragment ion of some labile aggregates. This explains why no corresponding carbon signal of thiocyanate has been ever recorded by NMR in the previous examinations. It has been noticed that 10a′ decomposed slowly in aqueous solution at room temperature. Degradation product of 10a′ is 4-pyridone (10a″) (Fig. 4), which is formed by bromide-associated dealkylation similar to Michaelis-Arbuzov reaction.

Fig. 4.

Structure proposal of m/z 355 (10a) and synthesized sample (10a′).

NMR of 10a′: 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 8.88 (s, 1H), 7.56 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.09 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.98 (dd, J = 2.4, 9.0 Hz, 1H), 4.59 (s, 2H), 4.30 (s, 3H), 3.80 (s, 3H), 2.61 (s, 3H), 2.60 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 172.9, 158.3, 149.1, 146.6, 142.0, 131.6, 128.0, 118.8, 115.7, 112.5, 97.0, 62.6, 56.0, 33.9, 16.0, 13.6. high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) of [M+H]+ theoretical 355.1223, found 355.1270.

NMR of 10a″: 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 7.78 (s, 1H), 7.58 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.14 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.99 (dd, J = 2.4, 9.0 Hz, 1H), 4.46 (s, 2H), 3.87 (s, 3H), 2.26 (s, 3H), 1.91 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 178.7, 157.6, 144.3, 141.7, 138.5, 126.0, 124.2, 117.5, 115.7, 114.2, 97.6, 56.0, 32.9, 14.0, 12.4. HRMS of [M+H]+ theoretical 341.1067, found 341.1096.

3.6. Colorimetric analysis

Colorimetric analysis experiments have been also carried out for the determination of cyanide. Hereby, the colorimetric test kit VISOCOLOR® ECO Cyanide (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) was employed. The solution system applied in the colorimetric test appears to influence the results dramatically. In the water/methanol solution, all the colorimetric tests of cyanide were negative. Meanwhile, several cyanide test results in a water/acetonitrile solution were positive, which turned to be false positive results later when compared with the control group. According to literature and product instruction, the cyanide analysis with the chloramine T/isonicotinic acid/1,3-dimethyl barbiturate system is susceptible to the interference of thiole, thiocyanate, halide ions, etc [15,16]. Since no cyanide ion in 1a or in its protolytic solution has been observed, the thiocyanate 10a should be a rearrangement product formed in situ during the CID process. The same solvent effect observed by the protonolysis and the colorimetric tests indicates that water/acetonitrile solution system benefits the formation of such aggregates.

3.7. Chemical derivatization for MS

In order to verify the origin of the thiocyanate 10a, chemical derivatization experiments have been performed. Two derivatization reagents, cysteamine 11 and dimedone 12, have been chosen, which are capable of capturing reactive intermediates such as disulfide, sulfenic acid, thiole as well as thiocyanate [4,[16], [17], [18], [19], [20]]. After protonolysis for 30 min, when the mass spectral response of omeprazole 1a or sulfenic acid 2a at m/z 346.12 disappeared, derivatization reagents were added to the reaction mixture. Along with the vanishing of 10a at m/z 355.12, derivatization products 8a, 13a and 14a have been detected by MS (Fig. 5). In both of the experiments, thioether 8a was the main component in the reaction mixture after the derivatization (Fig. 6). The formation of disulfide 13a is literature known, as to the formation of thioether 8a through a further reaction between disulfide 13a and cysteamine 11. However, if 10a does exist as a real entity in the solution, the consumption of 10a at m/z 355.12 during the derivatization must lead to the release of cyanide. Actually, cyanide could be found neither in cysteamine nor in dimedone treated sample by MS under negative mode. The absent of the cyanide fragment after derivatization further supports our hypothesis that the 10 is merely a MS species.

Fig. 5.

Chemical derivatization of the 1a protolytic sample.

Fig. 6.

Differential derivatization product profiles of protolytic sample and 10a′.

The MS2 patterns of the derivatization products 13a and 14a are quite similar to that of 10a. The signal intensity of their common sulfonamide fragment 3a is more intensive by 13a than by 14a or 10a (Figs. S5A−C). The different MRM transition efficiency of sulfonamide 3a can be addressed to the different bond dissociation energies between the S–S bond (65 kcal/mol) by 13a and the S–C bond (72 kcal/mol) by 10a and 14a. This result matches our structural proposal of 10a perfectly.

The derivatization experiments have been then carried out with the synthesized thiocyanate 10a′ (Figs. S5D−G). The reaction between 10a′ and dimedone 12 give thioether 14a as the only product. The derivatization product profiles of 10a’ can be well explained by the nucleophilic reactivity of cysteamine and dimedone. In comparison, the nucleophilicity of cysteamine is better than dimedone. Differential product profiles correctly match the electrophilic reactivity of the thiocyanate group. Accordingly, the complicated product profiles by 1a can be acutely explained as derivatization products of series of reactive intermediates, such as 5a, 7a or 9a. Therefore, the disappearance of m/z 355.12 should be rather attributed to the consumption of these reactive intermediates, namely its precursor species.

3.8. Precursor ion scan

By the precursor ion scan of 10a, series of precursor ions have been identified, such as m/z 764.85, 769.61 and 991.90 (Fig. S6A). The structures of these precursor ions remained unclear, but all of these precursor ions can give rise of m/z 355.12 as the only product ion under a low CE by MRM experiment. These results support the proposal that the signal of [M+10]+ is one kind of common CID fragment of some labile aggregates. In order to confirm this speculation, hybrid experiments have been carried out with synthesized structural analogues. Structural analogues with partially identical moieties are likely to aggregate together during ESI process. If such metastable aggregates do exist, one kind of hybrid precursor ion must exist, when two kinds of PPIs analogues have been mixed together and hydrolyzed.

First, omeprazole 1a and its analogue 1g (Fig. 7) have been investigated separately. The corresponding [M+10]+ fragments in the protolytic samples have been observed, i.e. 10a at m/z 355.12 and 10g at m/z 409.09 (Figs. S6A and B). Their precursor ions have been collected individually. Then, 1a and 1g have been mixed and hydrolyzed. The precursor ion scans of 10a and 10g in the mixed protolytic sample are basically consistent with their individual collected scans, but with several additional signals (Figs. S6C and D). Among these newly emerged signals, a common precursor ion at m/z 818.7 has been identified, whose MS2 fragments contained m/z 355.12 and 409.09 simultaneously (Fig. S6E). The result of mixed protolytic experiment by pantoprazole 1b and its analogue 1h (Fig. 7) was quite the same. By the precursor ion scan of [M+10]+ fragments of 10b (m/z 393.08) and 10h (m/z 377.09), a hybrid precursor ion at m/z 824.1 has been identified. The hybrid experiments have been then extended across all of the PPIs. Two series of hybrid precursor ions with the same pattern have been identified, namely, [set x+set y+54]+ and [set x+set y−28]+. The observed common hybrid precursor ions of the mixed PPIs in Fig. S7 were listed in Table 2. The presence of systematical hybrid precursor ions is an auxiliary evidence for the existence of such a metastable aggregation state. More importantly, the origin of the [M+10]+ fragments 10 turned out to be the product ions thereof and formed in situ by CID, instead of deriving from some cyanide impurity.

Fig. 7.

Synthesized derivates and the corresponding [M+10]+ fragments.

Table 2.

Hybrid precursor ions between 10s.

| Hybrid precursor ions between 10s out of the set x and y | set x |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| m/z369.13 (10d) | m/z379.08 (10c) | m/z 393.08 (10b) | ||

| set y | m/z355.12 (10a) | m/z778.43a, 696.38b | m/z788.43a, 706.39b | m/z802.44a, 720.40b |

| m/z 393.08 (10b) | m/z816.45a, 734.40b | m/z826.45a, 744.41b | – | |

| m/z379.08 (10c) | m/z802.44a, 720.40b | – | – | |

a [set x+set y+54]+; b [set x+set y−28]+.

4. Conclusion

A common mass spectral response in art of [M+10]+ in series of protolytic samples of PPIs has been identified as pyridinium thiocyanate 10 after a comprehensive assessment. This structure proposal has been confirmed with the synthesized derivate of omeprazole (10a′). When fitting together the puzzle of the solvent effect, colorimetric analyses, chemical derivatization and precursor ion scan, the origin of these species becomes distinct. It turns to be a product ion of labile pyridinium aggregates formed in situ by CID. This explanation is consistent with all the experimental observations. The discovery of such common mass spectrometry intermediates may not only ease the anxiety of pharmaceutical companies, but also provide insight into the genesis of “ghost signals” by ESI-MS.

CRediT author statement

Dong Sun: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Original draft preparation; Chunyu Wang: Investigation; Yanxia Fan: Supervision; Jingkai Gu: Resources, Writing - Reviewing and Editing, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos.: 82030107 and 81872831) and the National Science and Technology Major Projects for significant new drugs creation of the 13th five-year plan (Grant Nos.: 2017ZX09101001 and 2018ZX09721002007).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Xi'an Jiaotong University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpha.2023.04.011.

Contributor Information

Yanxia Fan, Email: 86884898@qq.com.

Jingkai Gu, Email: gujk@jlu.edu.cn.

Appendix ASupplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Shin J.M., Cho Y.M., Sachs G. Chemistry of covalent inhibition of the gastric (H+, K+)-ATPase by proton pump inhibitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:7800–7811. doi: 10.1021/ja049607w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shin J.M., Munson K., Vagin O., et al. The gastric HK-ATPase: structure, function, and inhibition. Pflugers Arch. 2009;457:609–622. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0495-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brändström A., Lindberg P., Bergman N.Å., et al. Chemical reactions of omeprazole and omeprazole analogues. I. A survey of the chemical transformations of omeprazole and its analogues. Acta Chem. Scand. 1989;43:536–548. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brändström A., Bergman N.Å., Lindberg P., et al. Chemical reactions of omeprazole and omeprazole analogues. II. Kinetics of the reaction of omeprazole in the presence of 2-mercaptoethanol. Acta Chem. Scand. 1989;43:549–568. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ward R.M., Kearns G.L. Proton pump inhibitors in pediatrics: Mechanism of action, pharmacokinetics, pharmacogenetics, and pharmacodynamics. Paediatr. Drugs. 2013;15:119–131. doi: 10.1007/s40272-013-0012-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shin J.M., Kim N. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the proton pump inhibitors. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2013;19:25–35. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2013.19.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang S., Zhang D., Wang Y., et al. Gradient high performance liquid chromatography method for simultaneous determination of ilaprazole and its related impurities in commercial tablets. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2015;10:146–151. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bogseth R., Edgcomb E., Jones C.M., et al. Acetonitrile adduct formation as a sensitive means for simple alcohol detection by LC-MS. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2014;25:1987–1990. doi: 10.1007/s13361-014-0975-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rackur G., Bickel M., Fehlhaber H.W. 2-((2-Pyridylmethyl)sulfinyl)benzimidazoles: acid sensitive suicide inhibitors of the proton transport system in the parietal cell. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1985;128:477–484. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(85)91703-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sturm E., Krüger U., Senn-Bilfinger J., et al. (H+-K+)-ATPase inhibiting 2-[(2-pyridylmethyl)sulfinyl] benzimidazoles. 1. Their reaction with thiols under acidic conditions. Disulfide containing 2-pyridiniobenzimidazolides as mimics for the inhibited enzyme. J. Org. Chem. 1987;52:4573–4581. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Senn-Bilfinger J., Krüger U., Sturm E., et al. (H+-K+)-ATPase inhibiting 2-[(2-pyridylmethyl)sulfinyl] benzimidazoles. 2. The reaction cascade induced by treatment with acids. Formation of 5H-pyrido[1',2':4,5] [1,2,4]thiadiazino [2,3-a] benzimidazol-13-ium salts and their reactions with thiols. J. Org. Chem. 1987;52:4582–4592. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krüger U., Senn-Bilfinger J., Sturm E., et al. (H+-K+)-ATPase inhibiting 2-[(2-Pyridylmethyl)sulfinyl] benzimidazoles. 3. Evidence for the involvement of a sulfenic acid in their reactions. J. Org. Chem. 1990;55:4163–4168. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kohl B., Sturm E., Senn-Bilfinger J., et al. (H+, K+)-ATPase inhibiting 2-[(2-pyridylmethyl)sulfinyl] benzimidazoles. 4. A novel series of dimethoxypyridyl- substituted inhibitors with enhanced selectivity. The selection of pantoprazole as a clinical candidate. J. Med. Chem. 1992;35:1049–1057. doi: 10.1021/jm00084a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brändström A., Bergman N.Å., Grundevik I., et al. Chemical reactions of omeprazole and omeprazole analogues. III. Protolytic behaviour of compounds in the omeprazole system. Acta Chem. Scand. 1989;43:569–576. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maleki B., Hemmati S., Tayebee R., et al. One-pot synthesis of sulfonamides and sulfonyl azides from thiols using chloramine-T. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2013;96:2147–2151. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rudyk O., Eaton P. Biochemical methods for monitoring protein thiol redox states in biological systems. Redox Biol. 2014;2:803–813. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brändström A., Lindberg P., Bergman N.Å., et al. Chemical reactions of omeprazole and omeprazole analogues. IV. Reactions of compounds of the omeprazole system with 2-mercaptoethanol. Acta Chem. Scand. 1989;43:577–586. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brändström A., Lindberg P., Bergman N.Å., et al. Chemical reactions of omeprazole and omeprazole analogues V. The reaction of N-alkylated derivatives of omeprazole analogues with 2-mercaptoethanol. Acta Chem. Scand. 1989;43:587–594. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brändström A., Lindberg P., Bergman N.Å., et al. Chemical reactions of omeprazole and omeprazole analogues VI. The reactions of omeprazole in the absence of 2-mercaptoethanol. Acta Chem. Scand. 1989;43:595–611. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta V., Carroll K.S. Profiling the reactivity of cyclic C-nucleophiles towards electrophilic sulfur in cysteine sulfenic acid. Chem. Sci. 2016;7:400–415. doi: 10.1039/c5sc02569a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.