Abstract

Fexofenadine is useful in various allergic disease treatment. However, the pharmacokinetic variability information and quantitative factor identification of fexofenadine are very lacking. This study aimed to verify the validity of previously proposed genetic factors through fexofenadine population pharmacokinetic modeling and to explore the quantitative correlations affecting the pharmacokinetic variability. Polymorphisms of the organic-anion-transporting-polypeptide (OATP) 1B1 and 2B1 have been proposed to be closely related to fexofenadine pharmacokinetic diversity. Therefore, modeling was performed using fexofenadine oral exposure data according to the OATP1B1- and 2B1-polymorphisms. OATP1B1 and 2B1 were identified as effective covariates of clearance (CL/F) and distribution volume (V/F)-CL/F, respectively, in fexofenadine pharmacokinetic variability. CL/F and average steady-state plasma concentration of fexofenadine differed by up to 2.17- and 2.20-folds, respectively, depending on the OATP1B1 polymorphism. Among the individuals with different OATP2B1 polymorphisms, the CL/F and V/F differed by up to 1.73- and 2.00-folds, respectively. Ratio of the areas under the curves following single- and multiple-administrations, and the cumulative ratio were significantly different between OATP1B1- and 2B1-polymorphism groups. Based on quantitative prediction comparison through a model-based approach, OATP1B1 was confirmed to be relatively more important than 2B1 regarding the degree of effect on fexofenadine pharmacokinetic variability. Based on the established pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationship, the difference in fexofenadine efficacy according to genetic polymorphisms of OATP1B1 and 2B1 was 1.25- and 0.87-times, respectively, and genetic consideration of OATP1B1 was expected to be important in the pharmacodynamics area as well. This population pharmacometrics study will be a very useful starting point for fexofenadine precision medicine.

Keywords: OATP1B1, OATP2B1, Fexofenadine, Population pharmacometrics, Genetic polymorphism

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

OATP1B1 and 2B1 are effective covariates for fexofenadine pharmacokinetic diversity.

-

•

Fexofenadine systemic clearance is associated with the interplay of OATP1B1 and 2B1.

-

•

OATP1B1 polymorphism has a major effect on fexofenadine pharmacokinetics.

-

•

An approach to precision medicine for fexofenadine through pharmacometrics studies.

1. Introduction

Fexofenadine is a drug with antihistamine action and can be prescribed for the treatment of various allergic conditions such as hay fever, conjunctivitis, eczema, and hives [1]. Fexofenadine is known to have fewer side effects that cause drowsiness than other anti-allergic drugs due to relatively selective antagonism of peripheral histamine receptors [2]. Therefore, fexofenadine has been steadily clinically applied from the past to the present due to its clinical preference over other antihistamine drugs and excellent patient compliance [1,3]. Despite the fairly long clinical history of fexofenadine [4], research on establishing a scientific quantitative dosage regimen for fexofenadine is very incomplete. That is, the clinical application of fexofenadine that has been performed so far relies on empirical usage, and a uniform dosage regimen (e.g., administration of 120 mg of tablets once a day, arbitrary increase or decrease in dose, and change in administration interval according to the severity of symptoms) is applied without considering the factors of diversity among individuals [5]. This may be due to the lack of inter-individual pharmacokinetic variability studies for fexofenadine and, above all, to the lack of approaches to identify quantitative pharmacokinetic variability.

According to past reports [6,7], fexofenadine is a substrate for organic-anion-transporting-polypeptide (OATP) 1B1 and 2B1, and there were differences in fexofenadine in vivo pharmacokinetic profiles depending on their genetic polymorphisms. SLCO1B1 and 2B1 have been reported as genes encoding the expression information of OATP1B1 and 2B1, respectively [8]. In addition, polymorphisms of SLCO1B1 521 thymine (T) > cytosine (C) and SLCO2B1 1457C > T are known as genetic factors that affect the functions of OATP1B1 and 2B1, respectively [8]. It has been reported that each single nucleotide polymorphism in SLCO1B1 521T > C and SLCO2B1 1457C > T is associated with reduced transport function of substrates by OATP1B1 and 2B1 in vitro [6,7]. OATP1B1 is a transporter associated with hepatic clearance in the liver [6,9], and OATP2B1 is expressed in the intestinal tract and is known to be a transporter involved in substrate absorption [7,10]. Therefore, sufficient causality was established that the pharmacokinetic profile results of fexofenadine, a substrate of OATP1B1 and 2B1, could be influenced by genetic polymorphisms of OATP1B1 or 2B1. However, the results reported in the past [6,7] only implied qualitative differences between genotypes, and there was no quantitative prediction and comparison in the group, and no determination of whether genetic polymorphisms were actually effective as covariates. Consequently, the variability of fexofenadine pharmacokinetics according to the genetic polymorphisms of OATP1B1 or 2B1 has not yet been clearly identified and remains a question.

Population pharmacokinetic variability and modeling studies of drugs are very useful scientific approaches to finding effective dosage regimens based on quantitative predictions [[11], [12], [13]]. Consideration of efficacy and safety through identification of the pharmacokinetic diversity of fexofenadine among individuals will be a very important concern in clinical practice [[14], [15], [16]]. Depending on the continuous exposure of fexofenadine, the pharmacokinetic variability among individuals may obviously appear, and this may lead to failure to reach the appropriate therapeutic target range or side effects (common reported side effects of fexofenadine: headaches, feeling sleepy, dry mouth, feeling sick, and dizziness) due to excessive accumulation. By identifying the main factors involved in the variability of fexofenadine pharmacokinetics among individuals and their quantitative correlations, effective clinical practice minimizing individual drug side effects and maximizing efficacy will be possible.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effectiveness of OATP1B1 and 2B1 as covariates in the pharmacokinetic variability of fexofenadine among individuals through a modeling approach. In addition, this study aimed to quantitatively evaluate the effect of the genetic polymorphism factors of OATP1B1 and 2B1 on fexofenadine pharmacokinetic diversity. This will enable more effective clinical application of fexofenadine than before by identifying the causes of fexofenadine's pharmacokinetic diversity and qualitatively/quantitatively predicting the results of the causative factors. In addition, the results of population pharmacokinetic analysis presented in this study will be very useful data for scientific clinical therapy setting and precision medicine considering genetic polymorphisms of fexofenadine, and will be important in increasing the understanding of drugs.

2. Experimental

2.1. Research process

This study was a retrospective approach and was conducted step by step in four major steps. First, a literature-based collection of fexofenadine pharmacokinetic profiles according to genetic polymorphisms of OATP1B1 (SLCO1B1 521T > C) and 2B1 (SLCO2B1 1457C > T) was performed [6,7]. Data reported [6,7] were mean plasma concentration values and standard deviations for each genotype population over time after oral exposure to fexofenadine. Therefore, the mean, maximum and minimum standard deviation, and 25% and 75% points within the standard deviation interval were extracted as representative data of each group, which was performed in a semi-automatic process using Web-Plot-Digitizer software (4.5 version). Second, based on the pharmacokinetic data for fexofenadine extracted from the literature [6,7], population modeling according to OATP1B1 and 2B1 was independently performed and validated. Third, differences in fexofenadine pharmacokinetics among genetic polymorphisms were quantitatively compared using established population modeling for OATP1B1 and 2B1. Quantitative pharmacokinetic comparisons between genotypes were performed based on simulation results of a population pharmacokinetic model following single or multiple exposures to fexofenadine. Fourth, fexofenadine pharmacodynamic differences between genetic polymorphisms of OATP1B1 and 2B1 were quantitatively compared. The quantitative comparison of pharmacodynamics between genotypes was performed with the newly derived relational expression of the effect pattern according to the degree of fexofenadine plasma exposure based on the pre-established [17] population pharmacokinetics-pharmacodynamics model of fexofenadine. Here, the pre-established fexofenadine pharmacokinetics-pharmacodynamics model was able to roughly be applied to the general population without considering effective covariates to explain the diversity of pharmacokinetics between individuals. And pharmacodynamics in the model was established based on the previously reported results [18] of wheal area changes (closely related to the pharmacological mechanism of histamine inhibition by fexofenadine) after oral administration of fexofenadine. Fig. 1 shows the workflow of this study.

Fig. 1.

Step-by-step workflow of this study. OATP: organic-anion-transporting-polypeptide.

2.2. Population pharmacokinetic modeling

The fexofenadine pharmacokinetic profile data according to OATP1B1 or 2B1 genetic polymorphisms in healthy adults derived from past reports [6,7] became the basic data for this population pharmacokinetic model development study. Fexofenadine pharmacokinetic profile data according to OATP1B1 genetic polymorphisms were presented for TT, TC, and CC groups in SLCO1B1 521T > C [6]. And a significant difference (P < 0.05) between groups was confirmed in fexofenadine pharmacokinetic profile data according to OATP2B1 genetic polymorphisms, which was presented by group for CC (T allele non-carrier) and CT/TT (T allele carriers) in SLCO2B1 1457C > T [7]. Data were identified as being obtained under tightly controlled conditions with formal clinical trial protocol approval. In addition, physiological factors among the test groups were homogeneous without large differences.

Construction and analysis of fexofenadine's population pharmacokinetic model were performed using a non-linear mixed effects model approach using Phoenix NLME 8.3 version (Certara Inc., Princeton, NJ, USA). In addition, the estimation of population pharmacokinetic parameters for fexofenadine was performed in the first-order conditional estimates method with extended least squares estimation (with ŋ–ε interaction). For model establishment, individual modeling was performed for each clinical study-derived data according to OATP1B1 or 2B1 genetic polymorphisms.

The development of the fexofenadine population pharmacokinetic model was carried out in two major steps. As a first step, a basic structural model was established that could well explain the concentration of fexofenadine in plasma according to the genetic polymorphism of OATP1B1 or 2B1 following oral administration of fexofenadine. These included the number of primary compartments, the lag-time (tlag) reflection of fexofenadine oral absorption and the mechanistic structuring of the absorption process, and the selection of error models to account for residual and inter-individual variabilities (IIV). As a second step, the search for effective covariates in explaining variations in the pharmacokinetics of fexofenadine among individuals was performed. Genetic polymorphisms of OATP1B1 or 2B1 were considered as potentially effective covariates. This is because current study was a retrospective approach based on previously reported genetic data [6,7], and the main purpose was to quantitatively evaluate the effects of OATP genetic polymorphisms on fexofenadine pharmacokinetic variability among individuals. Various statistical significance tools (such as twice the negative log likelihood (−2LL), Akaike's information criterion (AIC), and goodness-of-fit (GOF) plots) were used to select an appropriate model for each modeling stage. In addition, in the process of selecting an optimal model, statistical significance according to the total number of parameters applied to the model (increase or decrease in degrees of freedom) was considered as an indicator of model improvement. Statistical significance here was judged based on the P-value of 0.05 in the Chi-square distribution. For example, if the existing −2LL reduction was greater than 3.84 when the number of parameters in the model increased by one, this meant a significant improvement in the model, otherwise it was not a significant improvement. The genetic polymorphism information of OATP1B1 or 2B1, which were potential covariates, was treated as categorical data and they were sequentially applied to the IIV of the pharmacokinetic parameters used in the model. In the process of applying covariates, both forward addition and backward elimination were considered, and P-values of 0.05 and 0.01 respectively in the Chi-square distribution were set as statistical significance criteria. Covariates corresponding to a decrease in the objective function value (OFV) of greater than 3.84 (P < 0.05; as the number of parameters increases by one) were included in the base model (in the forward addition procedure). Covariates corresponding to the case where the increase in OFV was greater than 6.63 (P < 0.01; as the number of parameters decreases by one) through the backward elimination process were not removed from the model and were included. As a result, the model improvability was judged strictly at the significance level of P-value 0.01 according to the change in the degree of freedom of the model parameters.

2.3. Model validation

The population pharmacokinetic models of fexofenadine established considering OATP1B1 or 2B1 genetic polymorphisms were fully evaluated and validated visually or numerically using Phoenix NLME and R-software (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria). Evaluations of the model were performed using generally applied tools for population-scale drug quantification model validations [[11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]]. Applied tools include GOF (including distribution of residuals), visual predictive check (VPC), bootstrapping, and normalized prediction distribution error (NPDE). Specific approaches to each tool are presented in the Supplementary data (Section S1 Model validation tools).

2.4. Model simulation

In order to simulate the fexofenadine population pharmacokinetic model considering the genetic polymorphisms of OATP1B1 or 2B1, the final established and verified model structure was fixed. And the parameter values of the model were fixed as typical values for each genotype group, with categorical stratified values according to the genetic polymorphism covariate of OATP1B1 or 2B1. After fixation of the model structure and parameters, it was possible to simulate population scale models for various exposure scenarios according to changes in fexofenadine administration dose and frequency (such as multiple exposures). Model simulations were performed using Phoenix NLME's Simulation and Prediction engines (Certara Inc., Princeton, NJ, USA). In order to quantitatively and significantly evaluate the variability of fexofenadine pharmacokinetics for each genetic polymorphism group of OATP1B1 or 2B1 predicted from the model simulation, representative results of each simulation group were extracted. The results extracted from each group were a total of 9 of the 5th, 50th, and 95th of the population prediction range and 5%, 50%, and 95% of each, which satisfied representative sampling through a normal distribution. The extracted data of each group could be applied to the calculation of pharmacokinetic parameter values through non-compartment analysis (NCA), and as a result, the degree of pharmacokinetic variability between groups could be quantitatively compared. Pharmacokinetic parameters calculated or determined through NCA include half-life (t1/2), peak plasma concentration (cmax), time to reach cmax (tmax), area under the time-plasma concentration curve (AUC), volume of distribution (V/F), clearance (CL/F), and mean residence time (MRT). Methods for calculating or determining pharmacokinetic parameters through NCA are presented in the Supplementary data (Section S2 Non-compartment analysis).

Additionally, a quantitative comparison of fexofenadine pharmacodynamics between genetic polymorphisms of OATP1B1 or 2B1 was performed by referring to the pre-established [17] fexofenadine pharmacokinetics-pharmacodynamics model (briefly, the pre-established fexofenadine pharmacokinetics-pharmacodynamics model was able to predict the degree of antihistamine effect according to blood fexofenadine exposure in healthy adults without reflecting covariates). That is, the level of fexofenadine exposure in plasma (AUC) following fexofenadine administration was correlated with the level of drug efficacy and was appropriately formulated as a model, which could be used to quantify the level of efficacy based on the pharmacokinetics of fexofenadine in each genotype. Here, the degree of efficacy was defined as the area under the effect curve (AUEC) in the efficacy curve over time after administration of fexofenadine, and the calculation method is presented in the Supplementary data (Section S2 Non-compartment analysis).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Prior to the significance analysis between groups, confirmation of equal variance was performed through the F-test. Analysis of significant differences between the two groups was performed using the Student's t test. And analysis of significant differences between three or more groups was performed through one way-analysis of variance (with Tukey's post-hoc analysis). The default significance criterion was set at a P-value of 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Population pharmacokinetic modeling

Based on the results of independent pharmacokinetic studies [6,7] conducted on genetic polymorphisms of OATP1B1 or 2B1, a retrospective modeling analysis was attempted in this study. Table S1 [6,7] shows a summary of past clinical data information on which this modeling study was based. The basic structures of fexofenadine population pharmacokinetic models for OATP1B1 or 2B1 genetic polymorphisms could all be described as one-compartment with first-order absorption. For structures with more than two-compartments, the decrease in −2LL compared to the increase in the total number of parameters was not significant (reduction of −2LL; P > 0.05 and/or P > 0.01). Regarding the pattern of plasma concentration in the absorption phase, several structural multiple absorption compartment models, such as non-sequential two absorption compartments (having two or more absorption points with consideration of bioavailability) and sequential two absorption compartments (by applying two or more absorption rate constant parameters between successive absorption compartments), were tried, but no significant model improvement was found (reduction of −2LL; P > 0.05 and/or P > 0.01). Above all, the increase in the number of parameters in the absorption process was limited in the interpretation of the meaning of each added parameter and the general application of the model. Therefore, in this modeling study, setting up a complex structure and increasing the excessive number of estimated parameters were unnecessary in explaining the data. Rather, it would increase model uncertainty and interpretation errors based on limited drug information and experimental facts. tlag reflection in the uptake process resulted in significant model improvement as the number of parameters increased and/or decreased (reduction of −2LL; P < 0.05 and/or P < 0.01) only in the OATP2B1 model. As a result, the absorption processes of fexofenadine according to the genetic polymorphisms of OATP1B1 or 2B1 were explained without considering the mechanistic structure, and in the case of the OATP1B1 model, it was possible to explain without reflecting the tlag. The residual error portion of the fexofenadine population pharmacokinetic models for OATP1B1 or 2B1 genetic polymorphisms was fitted with a log-additive error model. When this was applied, the total number of parameters was maintained compared to other error models, and the degree of reduction of −2LL was the largest at more than 90%. The IIVs in population pharmacokinetic parameters of fexofenadine were evaluated by using an exponential error model, as shown in the following equation: Pi = Ptv × exp (ŋi), where ŋi is the random variable for the ith individual, which was normally distributed with mean 0 and variance ω2, Pi is the parameter value of the ith individual, and Ptv is the typical value of the population parameter. And as a result of step-by-step confirmation of the need to consider IIV in each parameter in relation to model improvement, IIV was reflected to all parameters (Ka, V/F, CL/F, and/or tlag) in the established model structures. Excluding IIV consideration of each parameter resulted in a significant model deterioration effect (reduction of −2LL; P < 0.05 and/or P < 0.01) by reducing the total number of parameters reflected in the model. Here, Ka denotes the oral absorption rate constant. The building steps for establishing the basic model structure of fexofenadine according to the OATP1B1 or 2B1 genetic polymorphisms are summarized in Tables S2 and S3.

OATP1B1 and 2B1 genetic polymorphisms were considered as candidate covariates that could explain IIV in fexofenadine pharmacokinetics. This was because the basic data of the modeling study was the pharmacokinetic results according to the genetic polymorphisms of OATP1B1 or 2B1, and the main purpose of this study was to identify the validity of OATP genetic factors in fexofenadine pharmacokinetic differences between groups. Finally, SLCO1B1 521T > C was selected as an effective covariate for CL/F in the explanation of fexofenadine pharmacokinetic variability among individuals according to OATP1B1 genetic polymorphisms. Significant model improvement (based on the P < 0.05 and P < 0.01 for forward selection and backward elimination) was confirmed as a result of incorporation of OATP1B1 genetic polymorphism factors into CL/F. On the other hand, incorporation of covariates into Ka or V/F did not lead to significant model improvement (based on the P > 0.05 and/or P < 0.01 for forward selection and/or backward elimination). In the description of fexofenadine pharmacokinetic variability among individuals according to OATP2B1 genetic polymorphisms, SLCO2B1 1457C > T was selected as an effective covariate for V/F and CL/F. As a result of incorporation of OATP2B1 genetic polymorphism factors into V/F and CL/F, both significant model improvement (based on the P < 0.05 and P < 0.01 for forward selection and backward elimination) was confirmed. In addition, it was confirmed that the model was significantly improved (with over 90% OFV reduction) when the Omega block was set considering the covariance between V/F and CL/F due to the simultaneous reflection of OATP2B1 genetic polymorphism factors into V/F and CL/F. Since CL/F is formally related to the product of the elimination rate constant (Ke) and V/F, it was necessary to consider the covariance of V/F-CL/F according to the reflection of the same covariate. Tables S4 and S5 summarize the model reflection steps and related results of the OATP1B1 or 2B1 genetic factors that were considered as potential covariates in the basic population pharmacokinetic model parameters established for fexofenadine. The formulas for the finally established population pharmacokinetic model parameters of fexofenadine were as follows:

| (Formula 1; OATP1B1 model) |

| (Formula 2; OATP1B1 model) |

| (Formula 3; OATP1B1 model) |

| (Formula 4; OATP2B1 model) |

| (Formula 5; OATP1B1 and 2B1 models) |

| (Formula 6; OATP2B1 model) |

where tv meant for typical values, dV/FdSLCO2B1 and dCL/FdSLCO2B1 indicate the degree of correlation between genotypes of SLCO2B1 and V/F and CL/F, respectively, and dCL/FdSLCO1B1 meant the degree of correlation between CL/F and SLCO1B1 genotypes.

The parameters and related values of the finally established fexofenadine population pharmacokinetic model according to the genetic polymorphisms of OATP1B1 or 2B1 are presented in Table S6 and S7, respectively. The relative standard errors (RSE) of the typical values of the pharmacokinetic parameters V/F, CL/F, Ka, and tlag were in reasonable agreement within 30% (Tables S6 and S7). The correlation values between pharmacokinetic parameters and covariates, dCL/FdSLCO1B1, dV/FdSLCO2B1, and dCL/FdSLCO2B1, also had RSEs within 30%. This implied that the parameter values of the models established in this study were derived robustly and that the model structure also had no major problems in explaining the data.

3.2. Model validation

The GOF plot results for each of the fexofenadine population pharmacokinetic models established in this study, taking into account the OATP1B1 or 2B1 polymorphisms, are presented in Figs. S1 and S2. Fexofenadine concentration values predicted by the population pharmacokinetic model of fexofenadine in the population or individual (population-predicted concentrations and/or individual-predicted concentrations) showed relatively good agreement with the experimentally obtained observations. The conditional weighted residuals (CWRES) were well distributed symmetrically with respect to zero. That is, CWRES were well distributed at random without any remarkably specific bias. In addition, the CWRES values at all points of predicted fexofenadine concentration or time in the population did not deviate from ±4. Quantile-quantile (QQ) plots of components of CWRES and individual weighted residuals were close to a straight line where the x- and y-axes were symmetrical (within ±4 ranges). Consequently, the GOF plot results (Figs. S1 and S2) suggested that the population pharmacokinetic model of fexofenadine finally established considering the genetic polymorphisms of OATP1B1 or 2B1 had no graphically significant issues.

Bootstrapping results for fexofenadine population pharmacokinetic models established for OATP1B1 or 2B1 genetic polymorphisms are presented in Tables S8 and S9, respectively. All the parameter values estimated in fexofenadine's final models were within the 95% confidence interval of the bootstrap analysis results (1000 replicates). And the estimates of the model parameters were close to the median estimated by bootstrap, with differences within 10%. As a result, bootstrapping analysis confirmed the robustness and reproducibility of the final established population pharmacokinetic model of fexofenadine (considering OATP1B1 or 2B1 genetic polymorphisms).

The results of the NPDE analysis of fexofenadine population pharmacokinetic models established taking into account OATP1B1 or 2B1 genetic polymorphisms are shown in Figs. S3 and S4. The assumptions of a normal distribution for the differences between predictions and observations of fexofenadine pharmacokinetics were acceptable. The QQ plots and histogram also confirmed the normality of the NPDE. Moreover, the NPDE results over time and predicted values were relatively symmetric with respect to zero (within ±4 ranges).

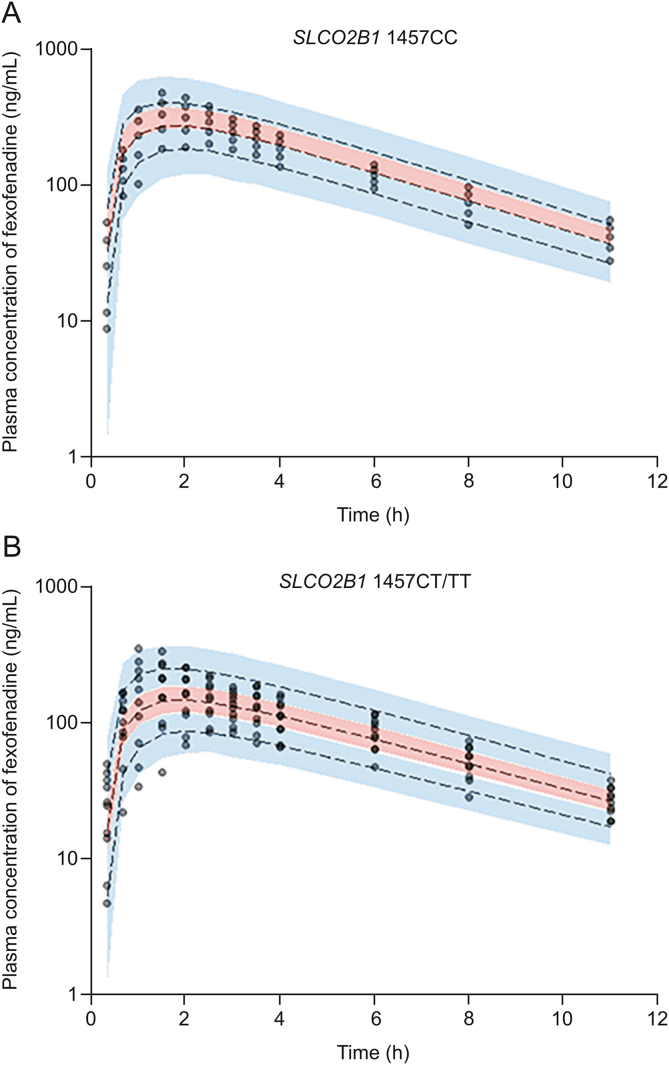

The stratified (according to SLCO1B1 521T > C genetic polymorphisms) VPC result of the fexofenadine population pharmacokinetic model (after single oral dose of 180 mg fexofenadine) is presented in Fig. 2. Most of the observation values (>90% of all data) of fexofenadine pharmacokinetics were well distributed within the stratified (according to SLCO1B1 genetic polymorphisms) 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the prediction values. The fexofenadine population pharmacokinetic model VPC results (after single oral dose of 60 mg fexofenadine) stratified according to the presence (CT and TT) or absence (CC) of the SLCO2B1 1457T allele are presented in Fig. 3. Most of the observation values (>90% of all data) of fexofenadine pharmacokinetics were also well distributed in 95% CIs stratified according to the presence or absence of the SLCO2B1 1457T allele. The VPC results suggested that fexofenadine's population pharmacokinetic models described the overall experimental data relatively well. VPCs were visually different between groups according to the SLCO1B1 and SLCO2B1 genetic polymorphisms (Fig. 2, Fig. 3). Plasma concentrations over time after oral exposure to fexofenadine continued to be higher and longer as the genotype of SLCO1B1 521 went from TT to TC to CC (Fig. 2). This was consistent with the reflection of the genetic polymorphic factor of OATP1B1 as an effective covariate of CL/F in the model. In addition, in the genotype of SLCO2B1 1457, the persistence of lower fexofenadine plasma concentrations in the presence of the T allele than in the absence thereof (Fig. 3) was consistent with the fact that the genetic polymorphism factor of OATP2B1 was reflected as an effective covariate of V/F and CL/F in the model. As a result, the final established population pharmacokinetic models of fexofenadine were at an acceptable level in the overall evaluation results, and there were no major problems.

Fig. 2.

Stratified visual predictive check results according to SLCO1B1 genetic polymorphisms following single oral exposure to 180 mg of fexofenadine (top) and pharmacokinetic profiles according to SLCO1B1 genetic polymorphisms following multiple oral exposures to 180 mg of fexofenadine (bottom; 12 h interval and 10 times dosing): (A) SLCO1B1 521TT, (B) SLCO1B1 521TC, and (C) SLCO1B1 521CC. Observed concentrations (after oral administration of 180 mg) were depicted by the dots. The 95th, 50th, and 5th percentiles of the predicted concentrations are represented by black dashed lines. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the predicted 5th and 95th percentiles are represented by the blue shaded regions. The 95% CIs for the predicted 50th percentiles are represented by the red shaded regions. T: thymine; C: cytosine.

Fig. 3.

Stratified visual predictive check results according to SLCO2B1 genetic polymorphisms ((A) SLCO2B1 1457CC and (B) SLCO2B1 1457CC/TT) following single oral exposure to 60 mg of fexofenadine. Observed concentrations (after oral administration of 60 mg) were depicted by the dots. The 95th, 50th, and 5th percentiles of the predicted concentrations are represented by black dashed lines. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the predicted 5th and 95th percentiles are represented by the blue shaded regions. The 95% CIs for the predicted 50th percentiles are represented by the red shaded regions. C: cytosine; T: thymine.

3.3. Model simulation-based pharmacokinetic comparison

Model simulation was performed by the reflection of pharmacokinetic parameter value changes according to OATP genotypes, which are effective covariates in the finally established fexofenadine population pharmacokinetic model. The plasma concentration profiles of multiple oral exposures of fexofenadine according to the genotypes of SLCO1B1 521T > C could be estimated by non-parametric model simulation based on the VPC results obtained after single oral administration, and the results are presented in Fig. 2. Similar to the VPC results from the single dose, the average fexofenadine plasma concentration in the multiple exposure group tended to increase and last longer as the SLCO1B1 521T > C genotype moved from TT to TC to CC (Fig. 2). Quantitative pharmacokinetic results calculated based on single- and multi-dose VPC results of fexofenadine according to OATP1B1 genetic polymorphisms are presented in Table 1, Table 2, respectively. Significant differences were identified among the SLCO1B1 521T > C polymorphisms in cmax, AUC, V/F, CL/F, and MRT (P < 0.05). Among the results presented in Table 1, Table 2, a summary of comparisons between OATP1B1 genotype groups of parameters with significance is presented in Fig. 4. As confirmed in the VPC graph, AUC0−∞, cmax, and MRT increased significantly (P < 0.05) and CL/F decreased from TT to TC and CC in the SLCO1B1 521T > C genotype. In addition, the degree of quantitative difference between OATP1B1 genetic polymorphisms varied from approximately 0.46 to 2.20-fold. It was also confirmed that the average plasma concentration in steady-state can vary up to 2.20 times between OATP1B1 genotypes. Although the difference was not significant at 1.00–1.03 times, the average accumulation ratio (R) among the OATP1B1 genetic polymorphism groups tended to increase (from TT to TC and CC), and the AUC ratio was significantly higher in SLCO1B1 521CC. This implied that the SLCO1B1 521T > C genetic polymorphisms increased plasma accumulation during multiple exposures to fexofenadine, and the degree may be significant in the CC genotype.

Table 1.

Pharmacokinetic parameter values for each genotype group calculated with population pharmacokinetic predictions of 5th−5%, 5th−50%, 5th−95%, 50th−5%, 50th−50%, 50th−95%, 95th−5%, 95th−50%, and 95th−95% (percentage of total population−percentage in range), as a result of the fexofenadine population pharmacokinetic model visual predictive check established by considering the organic-anion-transporting-polypeptide 1B1 (OATP1B1) genetic polymorphism as a covariate (following single oral exposure to 180 mg fexofenadine). The 5th, 50th, and 95th mean 5th, 50th, and 95th percentiles of the predicted concentrations for each group; the 5%, 50%, and 95% mean 5%, 50%, and 95% confidence interval (CI) ranges in each percentile.

| Parameters |

SLCO1B1 521T > C genotypes |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| TT | TC | CC | |

| t1/2 (h) | 2.45 ± 0.27 | 2.52 ± 0.26 | 2.83 ± 0.46 |

| tmax (h) | 2.00 ± 0.00 | 2.00 ± 0.00 | 2.50 ± 0.25∗ |

| cmax (ng/mL) | 450.17 ± 124.22∗ | 561.64 ± 154.96∗ | 770.89 ± 214.36∗ |

| AUC0−t (h·ng/mL) | 2502.56 ± 833.74∗ | 3315.74 ± 1100.37∗ | 5258.51 ± 1721.99∗ |

| AUC0−∞ (h·ng/mL) | 2633.93 ± 918.31∗ | 3519.09 ± 1228.25∗ | 5792.42 ± 2101.14∗ |

| V/F (L) | 259.19 ± 58.86∗ | 200.51 ± 49.72∗ | 134.78 ± 26.29∗ |

| CL/F (L/h) | 75.87 ± 26.26∗ | 56.93 ± 20.18∗ | 34.86 ± 12.80∗ |

| MRT (h) | 4.44 ± 0.30∗ | 4.73 ± 0.34∗ | 5.62 ± 0.54∗ |

| R value a | 1.04 ± 0.01 | 1.04 ± 0.01 | 1.06 ± 0.03 |

R value meant the accumulation ratio and was calculated by the following formula: In the formula, k and τ represent the elimination rate constant of fexofenadine and the dosing interval (as 12 h) for multiple exposures, respectively.

∗P < 0.05 between SLCO1B1 521TT, TC, and CC groups. T: thymine; C: cytosine; t1/2: half-life; cmax: peak plasma concentration; tmax: time to reach cmax; AUC: area under the time-plasma concentration curve; V/F: volume of distribution; CL/F: clearance; MRT: mean residence time.

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic parameter values for each genotype group calculated with population pharmacokinetic predictions of 5th−5%, 5th−50%, 5th−95%, 50th−5%, 50th−50%, 50th−95%, 95th−5%, 95th−50%, and 95th−95% (percentage of total population−percentage in range), as a result of the fexofenadine population pharmacokinetic model visual predictive check established by considering the organic-anion-transporting-polypeptide 1B1 (OATP1B1) genetic polymorphism as a covariate [following multiple oral exposures to 180 mg fexofenadine (12 h interval and 10 times dosing)]. The 5th, 50th, and 95th mean 5th, 50th, and 95th percentiles of the predicted concentrations for each group; the 5%, 50%, and 95% mean 5%, 50%, and 95% confidence interval (CI) ranges in each percentile.

| Parameters |

SLCO1B1 521T > C genotypes |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| TT | TC | CC | |

| t1/2 (h) | 1.97 ± 0.63 | 1.84 ± 0.25 | 2.09 ± 0.46 |

| tmax (h) | 1.84 ± 0.29 | 1.93 ± 0.15 | 2.39 ± 0.31∗ |

| cmax (ng/mL) | 470.17 ± 137.78∗ | 593.83 ± 175.80∗ | 846.32 ± 268.89∗ |

| AUC108−120 (h·ng/mL) | 2633.14 ± 917.84∗ | 3518.62 ± 1227.54∗ | 5793.46 ± 2100.82∗ |

| AUC108−∞ (h·ng/mL) | 2750.95 ± 1013.51∗ | 3671.18 ± 1324.20∗ | 6231.77 ± 2445.98∗ |

| V/F (L) | 191.14 ± 36.08∗ | 145.23 ± 62.91∗ | 92.15 ± 14.61∗ |

| CL/F (L/h) | 73.41 ± 26.55∗ | 54.89 ± 19.87∗ | 32.98 ± 12.94∗ |

| MRT (h) | 4.35 ± 0.34∗ | 4.54 ± 0.23∗ | 5.27 ± 0.42∗ |

| cSS,mean (ng/mL) a | 219.49 ± 76.53∗ | 293.26 ± 102.35∗ | 482.70 ± 175.10∗ |

| AUC ratio b | 1.04 ± 0.02 | 1.04 ± 0.01 | 1.07 ± 0.03∗ |

cSS,mean was the mean plasma concentration of fexofenadine at steady-state.

The AUC ratio was the ratio for single and multiple exposures to fexofenadine and was calculated by the following formula: AUC108−∞ (according to multiple exposures)/AUC0−∞ (according to single exposure).

∗P < 0.05 between SLCO1B1 521TT, TC, and CC groups. T: thymine; C: cytosine; t1/2: half-life; cmax: peak plasma concentration; tmax: time to reach cmax; AUC: area under the time-plasma concentration curve; V/F: volume of distribution; CL/F: clearance; MRT: mean residence time.

Fig. 4.

Pharmacokinetic parameter values for each genotype group calculated with population pharmacokinetic predictions of 5th−5%, 5th−50%, 5th−95%, 50th−5%, 50th−50%, 50th−95%, 95th−5%, 95th−50%, and 95th−95% (percentage of total population−percentage in range), as a result of the fexofenadine population pharmacokinetic model visual predictive check established by considering the organic-anion-transporting-polypeptide (OATP) 1B1 genetic polymorphism as a covariate, following (A) single or (B) multiple (12 h interval and 10 times dosing) oral exposures to 180 mg fexofenadine. The values presented above the bar of the graph mean the ratio between average values in each group based on the average values of the SLCO1B1 521TT group. ∗P < 0.05 between SLCO1B1 521TT, TC, and CC groups. T: thymine; C: cytosine; CL/F: clearance; AUC: area under the time-plasma concentration curve; R value: accumulation ratio; cmax: peak plasma concentration; MRT: mean residence time; cSS,mean: mean plasma concentration of fexofenadine at steady-state.

The model for OATP2B1 genetic polymorphisms was simulated with the same dose for quantitative comparison with the model considering OATP1B1 genetic polymorphisms. In other words, the model established with the data at 60 mg administration was simulated by changing the dose to 180 mg, which was possible by referring to the dose linearity (in the dosage range of 10–800 mg) report in fexofenadine pharmacokinetics in the past [18]. As a result, the model simulation VPC results for single and multiple exposures to 180 mg fexofenadine (considering OATP2B1 genetic polymorphisms) are presented in Fig. 5. Average lower fexofenadine plasma concentration profiles were seen in carriers compared to SLCO2B1 1457T allele non-carriers. Table 3, Table 4 show the quantitative pharmacokinetic results calculated based on single- and multi-dose VPC results of fexofenadine according to OATP2B1 genetic polymorphisms. During single exposure, significant differences (P < 0.05) between genotypes were confirmed in all pharmacokinetic parameters except tmax, but during multiple exposures, significant differences between groups were confirmed only in t1/2, cmax, and MRT. Among the results presented in Table 3, Table 4, a summary of comparisons between OATP2B1 genotype groups of parameters with significance is presented in Fig. 6. During single exposure to fexofenadine, the SLCO2B1 1457CT/TT genotype showed a significantly (P < 0.05) lower AUC0−∞ and cmax in carriers than the T allele non-carrier, and increased CL/F, V/F, and R values. In addition, the degree of quantitative difference between OATP2B1 genetic polymorphisms varied from approximately 0.54 to 2.00-fold. It was confirmed that the average plasma concentration in steady-state can also differ by up to 0.61 times between OATP2B1 genotypes. The mean values of R and AUC ratios were higher than 1 for both T allele non-carriers and carriers of the SLCO2B1 1457C > T genotype, suggesting that multiple exposures to fexofenadine may result in plasma accumulation.

Fig. 5.

Stratified visual predictive check results according to SLCO2B1 genetic polymorphisms following single oral exposure to 180 mg of fexofenadine (top) and pharmacokinetic profiles according to SLCO2B1 genetic polymorphisms following multiple oral exposures to 180 mg of fexofenadine (bottom; 12 h interval and 10 times dosing): (A) SLCO2B1 1457CC and (B) SLCO2B1 1457CT/TT. The 95th, 50th, and 5th percentiles of the predicted concentrations are represented by black dashed lines. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the predicted 5th and 95th percentiles are represented by the blue shaded regions. The 95% CI for the predicted 50th percentiles are represented by the red shaded regions. C: cytosine; T: thymine.

Table 3.

Pharmacokinetic parameter values for each genotype group calculated with population pharmacokinetic predictions of 5th−5%, 5th−50%, 5th−95%, 50th−5%, 50th−50%, 50th−95%, 95th−5%, 95th−50%, and 95th−95% (percentage of total population−percentage in range), as a result of the fexofenadine population pharmacokinetic model visual predictive check established by considering the organic-anion-transporting-polypeptide 2B1 (OATP2B1) genetic polymorphism as a covariate (following single oral exposure to 180 mg of fexofenadine). The 5th, 50th, and 95th mean 5th, 50th, and 95th percentiles of the predicted concentrations for each group; the 5%, 50%, and 95% mean 5%, 50%, and 95% confidence interval (CI) ranges in each percentile.

| Parameters |

SLCO2B1 1457C > T genotypes |

|

|---|---|---|

| CC | CT/TT | |

| t1/2 (h) | 2.92 ± 0.13 | 3.38 ± 0.14∗ |

| tmax (h) | 1.72 ± 0.26 | 1.83 ± 0.25 |

| cmax (ng/mL) | 930.28 ± 474.74 | 503.06 ± 283.14∗ |

| AUC0−t (h·ng/mL) | 5110.29 ± 2500.48 | 2984.28 ± 1615.63∗ |

| AUC0−∞ (h·ng/mL) | 5617.20 ± 2708.82 | 3408.37 ± 1807.09∗ |

| V/F (L) | 166.90 ± 88.34 | 334.45 ± 197.19∗ |

| CL/F (L/h) | 38.89 ± 18.44 | 67.35 ± 36.20∗ |

| MRT (h) | 5.13 ± 0.20 | 5.82 ± 0.27∗ |

| R value a | 1.06 ± 0.01 | 1.09 ± 0.01∗ |

R value meant the accumulation ratio and was calculated by the following formula: In the formula, k and τ represent the elimination rate constant of fexofenadine and the dosing interval (as 12 h) for multiple exposures, respectively.

∗P < 0.05 between SLCO2B1 1457CC and CT/TT groups. T: thymine; C: cytosine; t1/2: half-life; cmax: peak plasma concentration; tmax: time to reach cmax; AUC: area under the time-plasma concentration curve; V/F: volume of distribution; CL/F: clearance; MRT: mean residence time.

Table 4.

Pharmacokinetic parameter values for each genotype group calculated with population pharmacokinetic predictions of 5th−5%, 5th−50%, 5th−95%, 50th−5%, 50th−50%, 50th−95%, 95th−5%, 95th−50%, and 95th−95% (percentage of total population−percentage in range), as a result of the fexofenadine population pharmacokinetic model visual predictive check established by considering the organic-anion-transporting-polypeptide 1B1 (OATP2B1) genetic polymorphism as a covariate (following multiple oral exposures to 180 mg of fexofenadine (12 h interval and 10 times dosing)). The 5th, 50th, and 95th mean 5th, 50th, and 95th percentiles of the predicted concentrations for each group; the 5%, 50%, and 95% mean 5%, 50%, and 95% confidence interval (CI) ranges in each percentile.

| Parameters |

SLCO2B1 1457C > T genotypes |

|

|---|---|---|

| CC | CT/TT | |

| t1/2 (h) | 2.92 ± 0.13 | 3.38 ± 0.14∗ |

| tmax (h) | 1.72 ± 0.22 | 1.79 ± 0.22 |

| cmax (ng/mL) | 994.91 ± 501.28 | 556.11 ± 309.22∗ |

| AUC108−120 (h·ng/mL) | 5615.91 ± 2706.02 | 3408.81 ± 1806.76 |

| AUC108−∞ (h·ng/mL) | 6038.29 ± 2873.34 | 3785.38 ± 1971.53 |

| V/F (L) | 154.15 ± 79.85 | 297.87 ± 170.51 |

| CL/F (L/h) | 35.94 ± 16.66 | 60.01 ± 31.29 |

| MRT (h) | 5.14 ± 0.19 | 5.79 ± 0.26∗ |

| cSS,mean (ng/mL) a | 468.10 ± 225.74 | 284.03 ± 150.59 |

| AUC ratio b | 1.08 ± 0.01 | 1.12 ± 0.01∗ |

cSS,mean was the mean plasma concentration of fexofenadine at steady-state.

The AUC ratio was the ratio for single and multiple exposures to fexofenadine and was calculated by the following formula: AUC108−∞ (according to multiple exposures)/AUC0−∞ (according to single exposure).

∗P < 0.05 between SLCO2B1 1457CC and CT/TT groups. T: thymine; C: cytosine; t1/2: half-life; cmax: peak plasma concentration; tmax: time to reach cmax; AUC: area under the time-plasma concentration curve; V/F: volume of distribution; CL/F: clearance; MRT: mean residence time.

Fig. 6.

Pharmacokinetic parameter values for each genotype group calculated with population pharmacokinetic predictions of 5th−5%, 5th−50%, 5th−95%, 50th−5%, 50th−50%, 50th−95%, 95th−5%, 95th−50%, and 95th−95% (percentage of total population−percentage in range), as a result of the fexofenadine population pharmacokinetic model visual predictive check established by considering the organic-anion-transporting-polypeptide (OATP) 2B1 genetic polymorphism as a covariate, following (A) single or (B) multiple (12 h interval and 10 times dosing) oral exposures to 180 mg of fexofenadine. The values presented above the bar of the graph mean the ratio between average values in each group based on the average values of the SLCO2B1 1457CC group. ∗P < 0.05 between SLCO2B1 1457CC and CT/TT groups. C: cytosine; T: thymine; CL/F: clearance; V/F: volume of distribution; R value: accumulation ratio; cmax: peak plasma concentration; AUC: area under the time-plasma concentration curve; cSS,mean: mean plasma concentration of fexofenadine at steady-state.

3.4. Model simulation-based pharmacodynamic comparison

The population pharmacokinetic modeling results established in this study were extended to a quantitative pharmacodynamic comparison of fexofenadine between OATP1B1 or 2B1 genotype populations. For this process, it was necessary to establish a quantitative connection between the degree of fexofenadine exposure in the plasma (according to the genetic polymorphisms of OATP1B1 or 2B1) and the drug efficacy. Therefore, a correlation model of AUEC according to fexofenadine AUC change in plasma was newly derived in this study from the previously secured [17] pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamics of fexofenadine. To this end, correlations between AUC and AUEC were quantified as a model through simulations according to dose change based on the fexofenadine pharmacokinetics-pharmacodynamics model previously studied [17]. Here, AUC and AUEC were parameters representing the level of exposure to fexofenadine in plasma and the level of efficacy according to the exposure time. Fig. 7 shows the AUC-AUEC correlation graph according to the change in fexofenadine exposure dose newly derived in this study. The results were best explained by the Weibull model, and the complete inclusion of the results within the 95% confidence and prediction ranges implied that the established AUC-AUEC correlation model could be applied reliably enough to predict quantitative fexofenadine efficacy in this study. The Weibull model is flexible enough to model a variety of data sets, so it is preferred for modeling a large number of skewed, nonlinear or symmetric data [19]. Here, the AUC-AUEC relationship with varying fexofenadine doses was non-linear, which was well explained by the Weibull model of flexibility. The equations and optimized parameter values of the AUC-AUEC correlation model are presented in Table 5. The RSE of all parameter values was low within 2%, and the mean values were sufficiently included in the 95% CI. In addition, AIC, which means the goodness of fit of the quantitative model, was low at 11.49, and the correlation coefficient was 1.00, showing excellent correlation between the data and the model.

Fig. 7.

Correlation graph between area under the time-plasma concentration curve (AUC0−∞) and area under the effect curve (AUEC) estimated using the established fexofenadine population pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamics model. The effect or pharmacodynamics here means the antihistamine level induced by fexofenadine.

Table 5.

The Weibull model a and parameter values between AUC0−∞ and area under the effect curve (AUEC) estimated using the established fexofenadine population pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamics model.

| Parameters | Mean ± standard error | Relative standard error (%) | 95% CI |

| A | 1846.55 ± 6.15 | 0.33 | 1820.08–1873.01 |

| B | 2028.31 ± 18.23 | 0.90 | 1949.85–2106.77 |

| C | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.75 | 0.02–0.03 |

| D | 0.45 ± 0.01 | 1.52 | 0.43–0.48 |

| AIC | 11.49 | – | – |

| Correlation coefficient | 1.00 | – | – |

a Weibull model: y = A – Bx exp(−C × xD), where x indicates AUC0−∞, y indicates AUEC, A indicates the asymptote parameter, B indicates scale parameter, C indicates curve growth-rate parameter, and D indicates the shape parameter.

−: no data; AUC: area under the time-plasma concentration curve; CI: confidence interval; AIC: Akaike's information criterion.

Table 6 shows the predicted AUEC values according to the OATP1B1 or 2B1 genetic polymorphisms calculated using the fexofenadine population pharmacokinetic models and the AUC-AUEC correlation model established in this study. Estimates of AUEC predictions were performed through interpolation within the range predicted by the AUC-AUEC correlation model. The differences in AUC-based AUEC in plasma after a single exposure to fexofenadine according to OATP1B1 or 2B1 genetic polymorphisms were 1.25 or 0.87-fold, respectively. Besides, during multiple exposures to fexofenadine, the AUC-based AUEC differences in plasma at steady-state according to OATP1B1 or 2B1 genetic polymorphisms were 1.25 or 0.89 times, respectively. This implied that there was a significant difference in the degree of exposure to fexofenadine in plasma depending on the genetic polymorphisms of OATP1B1 or 2B1, and thus a difference in AUEC, which indicates the degree of drug efficacy. That is, as the T allele is lost in the SLCO1B1 521T > C genotype (TT > TC > CC), the significantly increased concentration of fexofenadine in plasma (Table 1, Table 2) suggests that it can lead to an increase in efficacy up to approximately 1.25-fold. In addition, in the SLCO2B1 1457C > T genotype, significantly reduced plasma fexofenadine concentrations in carriers than in T allele non-carriers (Table 3) were implied to cause a decrease in efficacy by approximately 0.87-fold.

Table 6.

Area under the effect curve (AUEC) values for each organic-anion-transporting-polypeptide (OATP) genotype estimated using the AUC0−∞−AUEC correlation model derived using the established fexofenadine population pharmacokinetics-pharmacodynamics model. Estimated AUEC values were derived based on the average AUC0−∞ values (AUC0−∞ at single exposure; AUC108−∞ for multiple exposures) estimated using a population pharmacokinetic model considering the OATP genetic polymorphisms established in this study as covariates.

| Exposures | Predicted AUEC for OATP1B1 (h×%) |

Predicted AUEC for OATP2B1 (h×%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TT | TC | CC | CC | CT/TT | |

| Single dose | 1065.48 | 1163.73 | 1328.94 | 1319.04 | 1152.91 |

| Multiple dose | 1080.22 | 1178.02 | 1352.30 | 1342.26 | 1188.35 |

T: thymine; C: cytosine; AUC: area under the time-plasma concentration curve.

3.5. Effects of OATP1B1 and 2B1 on the pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic diversity of fexofenadine

This study was a retrospective modeling conducted based on the results of segmental pharmacokinetic profiles according to genetic polymorphisms of OATP1B1 or 2B1. Therefore, the establishment of a model that simultaneously considers the genetic polymorphisms of OATP1B1 and 2B1 has been limited. This is because the genetic polymorphic elements of OATP2B1 and 1B1 are inherent in the experimental data [6,7] according to the genetic polymorphism of OATP1B1 or 2B1, respectively. Therefore, through modeling practices for each genetic polymorphism, the search for genetic factors with a greater degree of influence on fexofenadine pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic variability among individuals was performed. Comparatively, the fexofenadine pharmacokinetics-pharmacodynamics of the genetic polymorphisms of OATP1B1 compared to OATP2B1 were more dominant. This is because the degree of variation in AUC and mean plasma concentration at steady-state according to the genetic polymorphisms of OATP1B1 was 2.20 times higher than the degree of variation (0.61 times) according to the genetic polymorphisms of OATP2B1 (Fig. 4, Fig. 6). In the AUEC predictions based on the AUC-AUEC correlation model, the difference according to the genetic polymorphisms of OATP1B1 was 1.25 times higher than the degree of variation (1.13–1.14 times) according to the genetic polymorphisms of OATP2B1. As a result, considering the genetic polymorphisms of OATP1B1 and 2B1 in relation to fexofenadine pharmacokinetic diversity will be the first and second key factors for fexofenadine precision medicine, respectively.

The selection of OATP1B1 and 2B1 as valid covariates for CL/F in the models established in this study suggested that there is a heterogeneous interplay between OATP1B1 and 2B1 in the systemic clearance of fexofenadine. That is, although both OATP1B1 and 2B1 are homologous transporters that use fexofenadine as a substrate, their main expression and action sites are liver and intestinal tract, respectively [9,20], which can be interpreted as interplay effect on systemic clearance by being involved in fexofenadine absorption in the intestinal tract and hepatic clearance.

4. Discussion

The fexofenadine population pharmacokinetic models established in this study could be explained with a one-compartment structure, which was performed based on plasma concentration data up to 12 h after a single oral administration of fexofenadine. Plasma fexofenadine concentration results according to OATP1B1 or 2B1 polymorphisms [6,7], which were the basis of modeling, were presented only up to 12 h after administration, or data could not be identified at points after 12 h. Therefore, in this study, modeling was performed based on plasma concentration data up to 12 h after a single oral exposure of fexofenadine. As mentioned in the Introduction section, OATP2B1 is a transporter mainly expressed in the gastrointestinal tract and is a factor directly involved in the absorption of orally administered fexofenadine into the body [20]. Consideration of IIV with reflection of tlag with respect to fexofenadine uptake in the model following the OATP2B1 genetic polymorphisms significantly improved the model with respect to the physiological uptake mechanism. In the pharmacokinetic profile data [7] performed on the OATP2B1 genetic polymorphisms, the number of sparse observations in the absorption phase will also be associated with model improvement according to tlag reflection. In IIV, the genetic polymorphism factors of OATP1B1 (SLCO1B1 521T > C) or 2B1 (SLCO2B1 1457C > T) were reflected as covariates for the parameters of CL/F and V/F, but tlag and Ka were not reflected. This suggested that differences in fexofenadine pharmacokinetics between groups according to OATP1B1 or 2B1 genetic polymorphisms were mainly caused by changes in CL/F and V/F. That is, it was possible to interpret that the genetic polymorphisms of OATP1B1, which are mainly expressed in the liver, are the factors that have a major effect on hepatic clearance through the transfer of fexofenadine into hepatocytes [6]. In addition, it was possible to interpret that the genetic polymorphisms of OATP2B1 had a significant correlation with intestinal clearance related to fexofenadine transit from the gastrointestinal tract to the blood and changes in volume of distribution. As a result, the genetic factors of OATP1B1 and 2B1 were identified as effective covariates related to CL/F and V/F variability of fexofenadine among individuals, and were identified as key factors that could explain changes in fexofenadine plasma concentration.

According to a previous report [21], polymorphisms in the ABCB1 gene encoding P-glycoprotein (P-gp) may be involved in the pharmacokinetic variations of fexofenadine. However, the direct involvement of ABCB1 genetic polymorphisms in fexofenadine's pharmacokinetic variants is highly controversial. For example, one report [21] showed inter-individual differences in fexofenadine pharmacokinetics according to ABCB1 gene polymorphisms (2677G > T/A and 3435C > T), whereas another report [22] did not identify differences in pharmacokinetics between genetic polymorphisms (3435C > T). Furthermore, Dickens et al. [23] reported that ABCB1 genetic polymorphisms (1236C > T, 2677G > T/A, and 3435C > T) do not affect P-gp function makes fexofenadine, even though it is a substrate of P-gp [22], very limited to be judged ABCB1 genetic factors as an effective covariate directly related to pharmacokinetic variability. In addition, the fact that ABCB1 genetic factors (1236C > T, 2677G > T/A, and 3435C > T) were not suitable as effective covariates in fexofenadine pharmacokinetic variability in our previous study [17] led to fexofenadine pharmacokinetic variability assessment being performed without consideration of ABCB1 genetic polymorphism. As a result, in this study, ABCB1 was excluded and the genetic polymorphisms of OATP1B1 and 2B1, which are more specific factors, were considered in fexofenadine pharmacokinetic diversity. This study implies the possibility that there are various factors still to be identified regarding the variability of pharmacokinetics of fexofenadine among individuals. That is, for example, in addition to OATP1B1 and 2B1 identified in this study, the interaction of fexofenadine with receptors (such as multidrug resistance-associated proteins 2, 3, and 4) expressed by ABCC genes [24] (with ABCC genetic polymorphism analysis) will need to be further confirmed in the future.

According to our recent related study [17], demographic factors in fexofenadine's inter-individual pharmacokinetic variability were not identified as valid covariates. This may be related to the approach based on the bioequivalence results performed on healthy adults. That is, since most of the demographic indicators in the healthy adult group fall within the normal range, the variability of the overall distribution is relatively small compared to the patient group. Therefore, finding demographic factors as effective covariates of fexofenadine has been difficult in a recent study [17]. In this study, demographic factors were not considered due to the limited information of clinical reports [6,7] that were the basis of modeling along with consideration of recent research results [17].

In the pharmacokinetic profile observations according to the SLCO2B1 1457C > T polymorphisms [7], cmax was lower in the CT/TT group compared to the CC group, but plasma concentrations were more consistent (Fig. 3). Even in the established model, cmax and AUC were significantly (P < 0.05) lower in the CT/TT group than in the CC group, and CL/F, t1/2, and MRT were higher (Table 3). Therefore, although the overall plasma exposure was lower in SLCO2B1 1457CT/TT according to the administration of the same dose of fexofenadine, the relative (compared to single administration) accumulation in the body could be higher with multiple administrations. This suggested that inhibition of fexofenadine uptake in SLCO2B1 1457CT/TT significantly lowered AUC and increased CL/F, but the rate of elimination of absorbed fexofenadine was rather lower in the CT/TT groups. In other words, it was implied that the genetic polymorphism of OATP2B1 is closely related to the initial absorption phase of fexofenadine in the gastrointestinal tract and may be a major factor involved in the degree of absorption (intestinal clearance) rather than the rate of absorption. In the model of OATP2B1 genetic polymorphisms, there was no significant difference between the SLCO2B1 1457CC and CT/TT groups in AUC, V/F, and CL/F when simulating multiple exposures to fexofenadine, unlike the results of single exposure (Table 3, Table 4). This was thought to be the reason that the effect of OATP2B1 was reduced during multiple exposures to fexofenadine compared to single exposures. The fact that no significant difference was found between the SLCO2B1 1457CC and CT/TT groups in the mean steady-state fexofenadine plasma concentration values (Table 4) may be related to the reduced effect of OATP2B1 during multiple exposures to fexofenadine. On the other hand, the significance of differences in pharmacokinetic parameters between groups of SLCO1B1 521 TT, TC, and CC according to OATP1B1 genetic polymorphisms remained the same as in single exposure in fexofenadine multiple-exposure simulation. Consequently, this provides additional evidence to suggest that the genetic polymorphic component of OATP1B1 may be relatively dominant compared to OATP2B1 in fexofenadine pharmacokinetic variability among individuals.

The degree of efficacy according to fexofenadine plasma exposure between each OATP1B1 or 2B1 genotype group predicted using the simulation tools of the models established in this study could be quantified using the AUC-AUEC correlation model. However, the AUC-AUEC correlation model here was derived based on the pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic results without any reflection of covariates in fexofenadine pharmacokinetic variability between subjects. That is, the AUEC quantification values obtained in this study (Table 6) were pharmacodynamic predictions based on differences in fexofenadine pharmacokinetics according to OATP genetic polymorphism factors. In the future, it will be necessary to explore effective covariates that affect the pharmacodynamic variability of fexofenadine among individuals. For example, even if the plasma exposure level of fexofenadine is the same, there may be significant differences in pharmacodynamics depending on the susceptibility of target receptors between individuals.

This study had to be conducted based on limited clinical data [6,7]. This was unavoidable due to the very limited number of reports available of fexofenadine concentration profile results together with OATP1B1 and 2B1 genetic polymorphism information in humans. Nevertheless, the results of this modeling study provide a scientific basis and useful direction for prospective large-scale clinical trials in the future.

This study is based on data from clinical trials conducted on healthy subjects. This was also an unavoidable limitation because there were no reports of OATP1B1 and 2B1 genotyping as well as clinical pharmacokinetic results for patient groups. In the future, clinical trials in various disease groups (such as chronic allergic disease and liver cirrhosis) will need to confirm whether the effects of the OATP1B1 and 2B1 covariates established in this study can be effectively applied to various disease groups. In addition, based on the modeling results, it will be necessary to further expand the pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic interaction studies between fexofenadine and concomitant drugs.

Through this study, we were able to provide useful scientific data for the efficient clinical application of fexofenadine, and as a result, we were able to take a step closer to precision medicine of fexofenadine. This is because the effectiveness and extent of effects of OATP1B1 and 2B1 on fexofenadine pharmacokinetic diversity among individuals, which had not been clearly reported previously, were clearly quantified.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a population pharmacokinetic model of fexofenadine considering genetic polymorphisms of OATP1B1 and 2B1 is reported. Besides, the established population pharmacokinetic models could quantitatively compare differences in fexofenadine pharmacokinetics according to OATP1B1 or 2B1 genotypes through simulation tools. This study confirms that the genetic factors of OATP1B1 and 2B1 are the most important to date in fexofenadine pharmacokinetic variability among individuals, suggesting that OATP genetic polymorphic factors need to be considered in setting dosage regimens. This study presents a very important starting point for fexofenadine's individualized drug therapy and precision medicine. In addition, it will be very useful to supplement existing knowledge limitations by reporting quantitative research results on fexofenadine pharmacokinetic diversity, which was previously insufficient.

CRediT author statement

Ji-Hun Jang and Seung-Hyun Jeong: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing - Original draft preparation, Reviewing and Editing; Yong-Bok Lee: Project administration, Resources, Writing - Reviewing and Editing, Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Xi'an Jiaotong University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpha.2023.04.001.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Church M.K., Church D.S. Pharmacology of antihistamines. Indian J. Dermatol. 2013;58:219–224. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.110832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meeves S.G., Appajosyula S. Efficacy and safety profile of fexofenadine HCl: A unique therapeutic option in H1-receptor antagonist treatment. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2003;112:S69–S77. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(03)01879-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawashima M., Harada S., Tango T. Review of fexofenadine in the treatment of chronic idiopathic urticaria. Int. J. Dermatol. 2002;41:701–706. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ansotegui I.J., Bernstein J.A., Canonica G.W., et al. Insights into urticaria in pediatric and adult populations and its management with fexofenadine hydrochloride. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2022;18 doi: 10.1186/s13223-022-00677-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simpson K., Jarvis B. Fexofenadine, Drugs. 2000;59:301–321. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200059020-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niemi M., Kivistö K.T., Hofmann U., et al. Fexofenadine pharmacokinetics are associated with a polymorphism of the SLCO1B1 gene (encoding OATP1B1) Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2005;59:602–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02354.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imanaga J., Kotegawa T., Imai H., et al. The effects of the SLCO2B1 c.1457C> T polymorphism and apple juice on the pharmacokinetics of fexofenadine and midazolam in humans. Pharmacogenet. Genom. 2011;21:84–93. doi: 10.1097/fpc.0b013e32834300cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalliokoski A., Niemi M. Impact of OATP transporters on pharmacokinetics. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2009;158:693–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00430.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith N.F., Figg W.D., Sparreboom A. Role of the liver-specific transporters OATP1B1 and OATP1B3 in governing drug elimination. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2005;1:429–445. doi: 10.1517/17425255.1.3.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamai I., Nezu J.-I., Uchino H., et al. Molecular identification and characterization of novel members of the human organic anion transporter (OATP) family. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;273:251–260. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeong S.-H., Jang J.-H., Lee Y.-B. Population pharmacokinetic analysis of lornoxicam in healthy Korean males considering creatinine clearance and CYP2C9 genetic polymorphism. J. Pharm. Investig. 2022;52:109–127. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeong S.-H., Jang J.-H., Cho H.-Y., et al. Population pharmacokinetic (Pop-PK) analysis of torsemide in healthy Korean males considering CYP2C9 and OATP1B1 genetic polymorphisms. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14 doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14040771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeong S.-H., Jang J.-H., Lee Y.-B. Pharmacokinetic comparison between methotrexate-loaded nanoparticles and nanoemulsions as hard- and soft-type nanoformulations: A population pharmacokinetic modeling approach. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13 doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13071050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeong S.-H., Jang J.-H., Cho H.-Y., et al. Population pharmacokinetic analysis of cefaclor in healthy Korean subjects. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13 doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13050754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeong S.-H., Jang J.-H., Cho H.-Y., et al. Population pharmacokinetic analysis of tiropramide in healthy Korean subjects. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12 doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12040374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jang J.-H., Jeong S.-H., Cho H.-Y., et al. Population pharmacokinetics of cis-, trans-, and total cefprozil in healthy male Koreans. Pharmaceutics. 2019;11 doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics11100531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jang J.-H., Jeong S.-H., Lee Y.-B. Establishment of a fexofenadine population pharmacokinetic (PK)-pharmacodynamic (PD) model and exploration of dosing regimens through simulation. J. Pharm. Investig. 2023;53:427–441. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Russell T., Stoltz M., Weir S. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and tolerance of single-and multiple-dose fexofenadine hydrochloride in healthy male volunteers. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1998;64:612–621. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(98)90052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rinne H. 1st ed. Chapman & Hall/CRC; Boca Raton, FL, USA: 2008. The Weibull Distribution: A Handbook. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Müller J., Keiser M., Drozdzik M., et al. Expression, regulation and function of intestinal drug transporters: An update. Biol. Chem. 2017;398:175–192. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2016-0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yi S.Y., Hong K.S., Lim H.S., et al. A variant 2677A allele of the MDR1 gene affects fexofenadine disposition. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004;76:418–427. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drescher S., Schaeffeler E., Hitzl M., et al. MDR1 gene polymorphisms and disposition of the P-glycoprotein substrate fexofenadine. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2002;53:526–534. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2002.01591.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dickens D., Owen A., Alfirevic A., et al. ABCB1 single nucleotide polymorphisms (1236C> T, 2677G>T, and 3435C>T) do not affect transport activity of human P-glycoprotein. Pharmacogenet. Genom. 2013;23:314–323. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e328360d10c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tian X., Swift B., Zamek-Gliszczynski M.J., et al. Impact of basolateral multidrug resistance-associated protein (Mrp) 3 and Mrp4 on the hepatobiliary disposition of fexofenadine in perfused mouse livers. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2008;36:911–915. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.019273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.