Abstract

Background:

Although observational studies have reported that depression is a risk factor for gastroesophageal reflux disease, it is difficult to determine the potential causal correlation. Thus, this study investigated the causal relevance of depression for gastroesophageal reflux disease using Mendelian randomization and provided new evidence for their association.

Methods:

Based on data from the UK Biobank, we assessed the causality of the 2 diseases by analyzing 135 458 severe depressive disorder cases and 41 024 gastroesophageal reflux disease cases. The causal inference was assessed using inverse-variance weighting, weighted median, Mendelian randomization–Egger, and weighted median methods. Simultaneously, pleiotropy and sensitivity analyses were used for quality control. Finally, we also explored whether depression affects gastroesophageal reflux disease through other risk factors.

Results:

A positive causal relationship between depression and gastroesophageal reflux disease was found in the inverse-variance weighted and weighted median methods, both of which were statistically significant [odds ratio = 1.011, 95% CI: 1.004-1.017, P = .001; odds ratio = 1.011, 95% CI: 1.004-1.020, P = .002)]. Sensitivity analyses were consistent with a causal interpretation, and the main deviation of genetic pleiotropy was not found (Intercept β = 0.0005; SE = 0.005, P = .908). The genetic susceptibility to depression was also associated with smoking, insomnia, and sleep apnea (odds ratio = 1.166, 95% CI: 1.033-1.316, P = .013; odds ratio = 1.089, 95% CI: 1.045-1.134; and odds ratio = 1.004, 95% CI: 1.001-1.006, P = .001, respectively).

Conclusion:

Our results verified a causal correlation that depression could slightly increase the risk of gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Keywords: Depression, gastroesophageal reflux disease, Mendelian randomization, UK Biobank

Main Points

Major depressive disorder (MDD) and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GORD) are common diseases, and there is a close relationship between the 2 diseases.

The results of observational studies on MDD and GORD are inconsistent.

Previous evidence of MDD and GORD causality are from observational studies.

Our results verified a causal correlation that depression could slightly increase the risk of GORD.

Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is a common disease caused by the reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus, causing discomfort symptoms and/or complications inside and outside the esophagus.1,2 Several observational studies have reported that genetic predisposition, smoking, drinking, insomnia, sleep apnea, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, obesity, and psychological abnormalities are common risk factors for developing GORD.1,3-6 Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a common psychological disease characterized by depression, decreased interest, and impaired cognitive function.7 Both the incidence and prevalence of depression and GORD have been increasing, eventually becoming a global health concern in recent years.8,9 Previous studies have found that depression and GORD are closely related and that there is an interaction between the 2 diseases.10-13 Systematic reviews have shown that the severity and frequency of GORD symptoms are closely related to the severity of depression.14 However, there are also unanswered key questions in depression and GORD, particularly regarding potential mechanisms underlying this comorbidity. Currently, it is unclear whether the association between GORD and depression comes from common genetic or environmental factors and whether these associations are causal.

Mendelian randomization (MR) with genetic association is a new epidemiological tool for assessing causality that cannot be confused with other risk factors.15 This method can provide strong causal evidence for the research and can effectively avoid the deviation caused by observational research.16 An MR study has been used to evaluate the effect of higher central adiposity on GORD, indicating that a higher waist–hip ratio increases the risk of GORD.17 In this study, we evaluated the potential causal role of depression in GORD and explored the potential mediators of the causal association between the two.

Materials and Methods

Genetic Variants Associated with Major Depressive Disorder

A meta-analysis of MDD in the genome-wide association studies (GWAS) was applied as an exposure set in this study, with 135 458 MDD cases and 344 901 controls among participants.18 The MDD cases were diagnosed using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV or the International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10). Based on strict inclusion criteria (P < 5 × 10−8), Wray et al18 reported that 44 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) played a significant role in MDD (Table S1). The 0.23% change in MDD was explained by these associated SNPs, and the instruments with large F‐statistics (value of 156) can strongly predict GORD.19

Supplementary Table 1.

Forty-four SNPs Associated with Major Depressive Disorder

| SNP | Chromosome | Position | Effect allele | Other allele | Frequency | Beta | Se | P | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs1432639 | 1 | 72813218 | A | C | 0.6187 | -0.0027 | 0.0083 | .746 | 140, 254 |

| rs159963 | 1 | 8504421 | A | C | 0.5671 | 0.0051 | 0.0085 | .5495 | 140, 254 |

| rs2389016 | 1 | 80799329 | T | C | 0.2744 | 4.00E-04 | 0.0096 | .9632 | 140, 254 |

| rs4261101 | 1 | 90796053 | A | G | 0.3543 | -0.0036 | 0.0086 | .6699 | 140, 254 |

| rs9427672 | 1 | 1.98E+08 | A | G | 0.2187 | -0.018 | 0.0101 | .07444 | 140, 254 |

| rs11682175 | 2 | 57987593 | T | C | 0.5333 | -0.0178 | 0.008 | .02626 | 140, 254 |

| rs1226412 | 2 | 1.57E+08 | T | C | 0.7859 | -0.005 | 0.01 | .6207 | 140, 254 |

| rs9862324 | 3 | 44433910 | T | C | 0.669 | -0.0085 | 0.0086 | .326 | 140, 254 |

| rs7430565 | 3 | 1.58E+08 | A | G | 0.5674 | 0.0027 | 0.008 | .7403 | 140, 254 |

| rs34215985 | 4 | 42047778 | C | G | 0.2135 | -0.0179 | 0.01 | .07425 | 140, 254 |

| rs27732 | 5 | 87992576 | A | G | 0.4167 | -0.0081 | 0.0083 | .3302 | 140, 254 |

| rs2018142 | 5 | 1.04E+08 | A | C | 0.5229 | -0.0085 | 0.0081 | .2922 | 140, 254 |

| rs116755193 | 5 | 1.24E+08 | T | C | 0.3786 | -0.0193 | 0.0085 | .02314 | 140, 254 |

| rs11135349 | 5 | 1.65E+08 | A | C | 0.4504 | 0.0207 | 0.0083 | .01254 | 140, 254 |

| rs4869056 | 5 | 1.67E+08 | A | G | 0.6311 | -5.00E-04 | 0.0089 | .9554 | 140, 254 |

| rs115507122 | 6 | 30737591 | C | G | 0.172 | -0.0526 | 0.0106 | .0000 | 140, 254 |

| rs9402472 | 6 | 99566521 | A | G | 0.2222 | -0.006 | 0.0099 | .5395 | 140, 254 |

| rs10950398 | 7 | 12264871 | A | G | 0.4074 | 0.011 | 0.0081 | .1762 | 140, 254 |

| rs12666117 | 7 | 1.09E+08 | A | G | 0.4652 | -0.0034 | 0.008 | .6718 | 140, 254 |

| rs1354115 | 9 | 2983774 | A | C | 0.6308 | 0.0092 | 0.0089 | .3049 | 140, 254 |

| rs10959913 | 9 | 11544964 | T | G | 0.765 | -0.0231 | 0.0098 | .01801 | 140, 254 |

| rs7856424 | 9 | 1.20E+08 | T | C | 0.2896 | 0.0087 | 0.0091 | .3379 | 140, 254 |

| rs7029033 | 9 | 1.27E+08 | T | C | 0.0796 | -0.0189 | 0.0151 | .2121 | 140, 254 |

| rs61867293 | 10 | 1.07E+08 | T | C | 0.206 | 0.0127 | 0.0099 | .2009 | 140, 254 |

| rs1806153 | 11 | 31850105 | T | G | 0.225 | -1.00E-04 | 0.0099 | .9951 | 140, 254 |

| rs4074723 | 12 | 23947737 | A | C | 0.401 | -0.0168 | 0.0091 | .06559 | 140, 254 |

| rs4143229 | 13 | 44327799 | A | C | 0.9189 | -0.0093 | 0.0148 | .5284 | 140, 254 |

| rs12552 | 13 | 53625781 | A | G | 0.4329 | 0.0051 | 0.0084 | .5459 | 140, 254 |

| rs4904738 | 14 | 42179732 | T | C | 0.555 | -0.009 | 0.0082 | .2716 | 140, 254 |

| rs915057 | 14 | 64686207 | A | G | 0.4302 | -0.0163 | 0.0083 | .05126 | 140, 254 |

| rs3742786 | 14 | 75373011 | A | G | 0.4488 | 0.0242 | 0.0079 | .002278 | 140, 254 |

| rs10149470 | 14 | 1.04E+08 | A | G | 0.4949 | -0.0213 | 0.008 | .007901 | 140, 254 |

| rs8025231 | 15 | 37648402 | A | C | 0.5519 | 0.0041 | 0.0083 | .6174 | 140, 254 |

| rs8063603 | 16 | 6310645 | A | G | 0.6568 | -0.0047 | 0.0089 | .6002 | 140, 254 |

| rs7198928 | 16 | 7666402 | T | C | 0.6256 | -0.0049 | 0.0084 | .5638 | 140, 254 |

| rs7200826 | 16 | 13066833 | T | C | 0.2605 | -0.0089 | 0.0096 | .3528 | 140, 254 |

| rs11643192 | 16 | 72214276 | A | C | 0.4027 | -0.0234 | 0.0082 | .004284 | 140, 254 |

| rs17727765 | 17 | 27576962 | T | C | 0.9147 | -0.012 | 0.015 | .4247 | 140, 254 |

| rs62099069 | 18 | 36883737 | A | T | 0.4246 | -0.0097 | 0.0084 | .2505 | 140, 254 |

| rs11663393 | 18 | 50614732 | A | G | 0.4713 | 0.0079 | 0.008 | .3242 | 140, 254 |

| rs1833288 | 18 | 52517906 | A | G | 0.7116 | 0.0192 | 0.0095 | .04256 | 140, 254 |

| rs12958048 | 18 | 53101598 | A | G | 0.3223 | -0.0151 | 0.0086 | .07798 | 140, 254 |

| rs5758265 | 22 | 41617897 | A | G | 0.2832 | 0.0173 | 0.0089 | .05145 | 140, 254 |

SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Genome-Wide Association Study Summary Data on Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Gastroesophageal reflux disease’s genome-wide association study summary data were from the UK Biobank (https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/).20 The GORD cases were defined by medical record ICD10. Totally, there were 41 024 GORD cases and 410 073 controls. There were 15 SNPs removed from the 44 SNPs in MDD, including palindromic with intermediate allele frequency and the result set lacked.

Summary Data of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Risk Factors

The association of MDD with previously reported risk factors for GORD was assessed by inverse variance weighting (IVW) to explore whether depression affects GORD through other risk factors. Smoking, drinking, body mass index, daytime sleeping, sleeplessness/insomnia, sleep apnea, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes were considered as possible mediating factors of GORD. The data of these factors were obtained from several widely used databases (Table 1).

Table 1.

Details of the Risk Factors Related to GWASs Included in Mendelian Randomization

| Phenotype | Consortium | Participants | PMID/Web Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major depressive disorder | A meta‐analysis of GWAS | 480 359 | 29700475 |

| Body mass index | A meta‐analysis of GWAS | 681 275 | 30124842 |

| Daytime dozing/sleeping (narcolepsy) | Neale Lab Consortium | 336 082 | http://www.nealelab.is/uk‐biobank |

| Hypertension | Neale Lab Consortium | 361 194 | http://www.nealelab.is/uk‐biobank |

| Type 2 diabetes | A meta‐analysis of GWAS | 701 27 | 29358691 |

| Cigarettes per day | GWAS and Sequencing Consortium of Alcohol and Nicotine use | 337 334 | 30643251 |

| Alcoholic drinks per week | GWAS and Sequencing Consortium of Alcohol and Nicotine use | 335 394 | 30643251 |

| Sleeplessness/insomnia | Neale Lab Consortium | 336 965 | http://www.nealelab.is/uk‐biobank |

| Sleep apnoea | Neale Lab Consortium | 361 194 | http://www.nealelab.is/uk‐biobank |

BMI, body mass index; GWAS, genome-wide association studies.

Statistical Analyses

According to MR guidelines, the IVW method has maximum statistical power when the instrumental variables (IVs) are all effective. Therefore, it was mainly used to evaluate the causal relationship between MDD and GORD risk.21 If at least 50% of the weights in the analysis is from IVs, the weighted median method provides a causal estimation.22 Even if all SNPs are ineffective tools, the MR–Egger method provides an effective estimation23. In addition, the MR–Egger Regression was used to evaluate horizontal pleiotropy. The robustness of significant results was evaluated by the leave-one-out sensitivity test. All MR analyses in this study were performed using R (version 4.0.3) with the “TwoSampleMR” package (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).24

Results

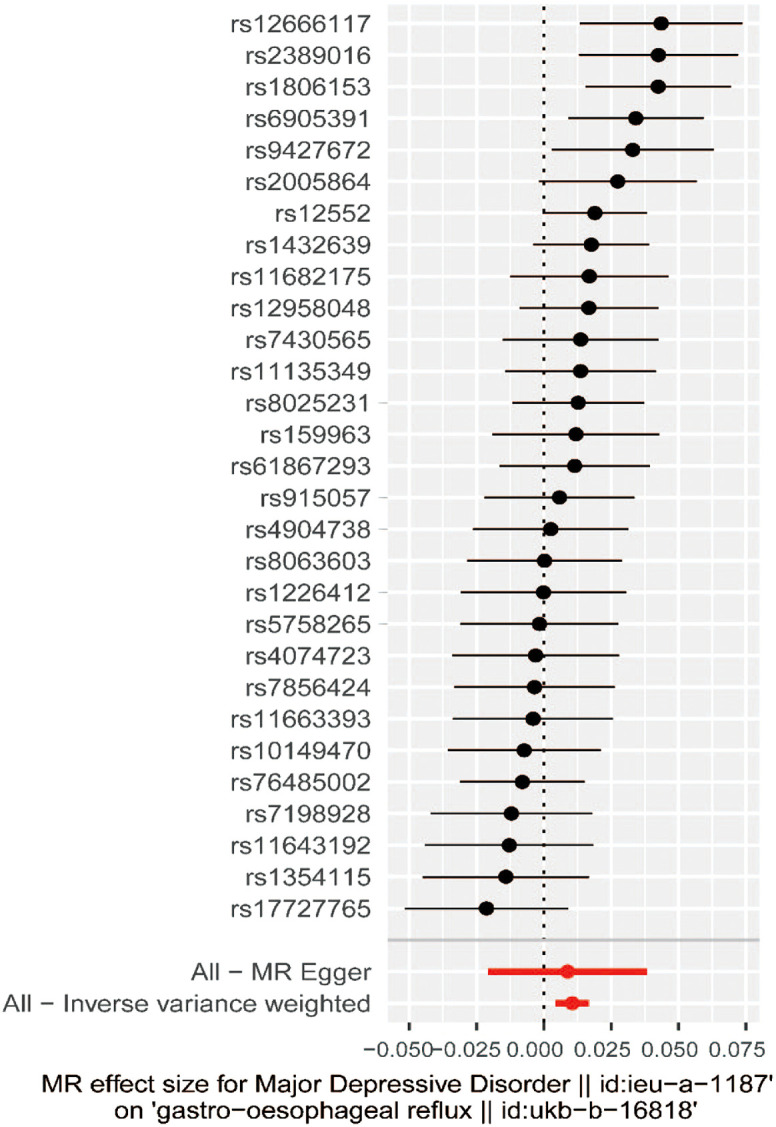

A total of 29 SNPs associated with MDD were used. Patients with MDD were 1.011-fold more likely to have GORD (95% CI: 1.004-1.017, P = .001) than those without MDD. In addition, a similar positive result was also found in the weighted median method (odds ratio [OR] = 1.011, 95% CI: 1.004-1.020, P = .002) (Figure 1). At the same time, the MR–Egger method and weighted mode obtained similar risk estimates, but neither was found to be statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Scatter plot of the effect of SNPs on major depressive disorder and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; MR, Mendelian randomization.

The MR–Egger method is usually used to test whether multiple IVs have horizontal pleiotropy. No significant intercept was found in this study (intercept β = 0.0005; SE = 0.005, P = .908), indicating the lack of horizontal pleiotropy. (Figure 2). The funnel plot can intuitively show the heterogeneity of SNPs; the funnel plot in this study was symmetrical as a whole, showing that there was no pleiotropy (Figure 3). The omission sensitivity analysis showed that the MR results were actually robust and not affected by the SNP (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of SNPs associated with major depressive disorder and their risk of gastro-oesophageal reflux. SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; MR, Mendelian randomization.

Figure 3.

Funnel plot of SNPs associated with major depressive disorder and their risk of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; MR, Mendelian randomization; IV, instrumental variable; 1/SEIV, instrument precision; βIV, in (OR) estimates.

Figure 4.

Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis of SNPs associated with major depressive disorder and risk of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; MR, Mendelian randomization.

Furthermore, the IVW also assessed the relationship between depression and previously reported risk factors for GORD to explore the potential factors that serve as mediators (Table 2). A statistical significance was found in smoking, sleeplessness/insomnia, and sleep apnea (OR = 1.166, 95% CI: 1.033-1.316, P = .013; OR = 1.089, 95% CI: 1.045-1.134, P < .001; and OR = 1.004, 95% CI: 1.001-1.006, P = .001, respectively).

Table 2.

Relationship Between Major Depressive Disorder Predicted by Genetic Data and Potential Risk Factors of GORD

| Outcomes | nSNPs | OR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body mass index | 27 | 1.022 | 0.917-1.140 | .689 |

| Daytime dozing/sleeping (narcolepsy) | 32 | 1.019 | 0.999-1.040 | .068 |

| Hypertension | 32 | 1.000 | 0.998-1.002 | .884 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 32 | 1.031 | 0.854-1.244 | .753 |

| Cigarettes per day | 31 | 1.166 | 1.033-1.316 | .013 |

| Alcoholic drinks per week | 31 | 1.000 | 0.955-1.048 | .992 |

| Sleeplessness/insomnia | 32 | 1.089 | 1.045-1.134 | <.001 |

| Sleep apnoea | 36 | 1.004 | 1.001-1.006 | .001 |

nSNP, number of single-nucleotide polymorphism; OR, odds ratio; GORD, gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Discussion

In this study, the causal relationship between depression and GORD was verified using publicly available summary statistics from several genetic consortia. The MR analysis showed that depression could slightly promote GORD. This result was conducive to a clear understanding of the relationship between depression and GORD, which may contribute to better prevention and treatment of GORD.

Observational studies have shown that depression can lead to an increased risk of reflux symptoms.25,26 Studies have shown that mental disorders are associated with the onset of reflux esophagitis, but no correlation was found between the severity of depression and the severity of reflux esophagitis.27 In addition, a study showed that patients with anxiety and depression had a 2.8-fold higher risk of GORD than those without anxiety and depression.25 In one study, patients with GORD with underlying mental disorders had postoperative satisfaction of 11.1%, compared with the 95.3% in patients without these diseases.28 Therefore, depression is usually considered to be a potential factor of GORD in observational studies. Unfortunately, due to the inevitable limitations of observational studies, the causal relationship between these diseases is difficult to be confirmed. Based on this background, MR analysis may be an important causal reasoning research tool. Through MR analysis, our results supported the hypothesis that depression is a risk factor for GORD.

It should be noted that the pathophysiological mechanism of the relationship between depression and GORD remains unclear. Existing studies point to the following possible explanations. Due to the influence of psychological factors, patients with depression can reduce the sensory threshold of the body and increase the sensation of esophageal stimulation.29,30 Studies have also shown that there is a close relationship between the brain and the gastrointestinal tract.31 Patients with depression may have increased lower esophageal sphincter relaxation and then aggravated GORD.32 The mechanism of psychological factors affecting reflux symptoms has also been confirmed in animal studies. The damage to esophageal epithelial tight junction in stressed rats leads to the decreased functionality of the esophageal mucosal barrier, which then increases the vulnerability of the esophagus to reflux.33 Some antidepressants may reduce the pressure of lower esophageal sphincter, cause esophageal dysfunction, and aggravate reflux symptoms.34,35 Patients with depression may alleviate depressive symptoms through an unhealthy lifestyle, and factors such as smoking, drinking, and unhealthy eating habits may increase the risk of GORD in patients with depression.32,36

We further explored whether some intermediate phenotypes play a role in the causal relationship between depression and GORD. We focused on some intermediate phenotypes and found that smoking, insomnia, and sleep apnea may play a role. In addition, a previous MR study showed that higher central adiposity is the causal determinant of the risk of GORD.17

Our study had several limitations. First, the related GWAS data were from populations of European ancestry, and GORD-related individuals were middle-aged and elderly people in the UK. Second, more result datasets related to GORD in MR analysis had not been further verified. Third, there were multiple subtypes in patients with depression and GORD, and further subgroup analysis may be necessary.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that there is a causal relationship between depression and GORD and that depression could slightly increase the risk of GORD.

Footnotes

Ethics Committee Approval: No ethical clearance was required for this research, for no patients were involved in the development of the research question or its outcome measures. Only secondary analysis was performed using published GWAS summary statistics available in the public domain.

Informed Consent: N/A.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept - G.C., X.Z., L.S.; Design - G.C., X.Z., L.S.; Supervision - X.Z., L.S.; Funding - All authors; Materials - G.C., J.X., J.Y., X.K.; Data Collection and/or Processing - G.C., J.X., J.Y., X.K., W.L.; Analysis and/or Interpretation - G.C., J.X., J.Y., X.K.; Literature Review - All authors; Writing - All authors; Critical Review - All authors.

Acknowledgments: The authors express their gratitude to the participants and research teams from UK Biobank who made the GWAS results publicly accessible.

Declaration of Interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Funding: This study received no funding.

References

- 1. Maret-Ouda J, Markar SR, Lagergren J. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: a review. JAMA. 2020;324(24):2536 2547. ( 10.1001/jama.2020.21360) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. GBD. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease collaborators. The Global, Regional, and National Burden of Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Disease in 195 Countries and Territories, 1990-2017: a Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;5(6):561 581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lindam A, Ness-Jensen E, Jansson C.et al. Gastroesophageal reflux and sleep disturbances: A bidirectional association in a population-based cohort study, the HUNT study. Sleep. 2016;39(7):1421 1427. ( 10.5665/sleep.5976) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wu ZH, Yang XP, Niu X, Xiao XY, Chen X. The relationship between obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome and gastroesophageal reflux disease: a meta-analysis. Sleep Breath. 2019;23(2):389 397. ( 10.1007/s11325-018-1691-x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fujiwara M, Miwa T, Kawai T, Odawara M. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in patients with diabetes: preliminary study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30(suppl 1):31 35. ( 10.1111/jgh.12777) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Keefer L, Palsson OS, Pandolfino JE. Best practice update: incorporating Psychogastroenterology Into management of digestive disorders. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(5):1249 1257. ( 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.045) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Otte C, Gold SM, Penninx BW.et al. Major depressive disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16065. ( 10.1038/nrdp.2016.65) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Malhi GS, Mann JJ. Depression. Lancet. 2018;392(10161):2299 2312. ( 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31948-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Richter JE, Rubenstein JH. Presentation and epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(2):267 276. ( 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.07.045) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Javadi SAHS, Shafikhani AA. Anxiety and depression in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disorder. Electron Phys. 2017;9(8):5107 5112. ( 10.19082/5107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chou PH, Lin CC, Lin CH.et al. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease in major depressive disorder: a population-based study. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(2):155 162. ( 10.1016/j.psym.2013.06.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yang XJ, Jiang HM, Hou XH, Song J. Anxiety and depression in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease and their effect on quality of life. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(14):4302 4309. ( 10.3748/wjg.v21.i14.4302) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kim SY, Kim HJ, Lim H, Kong IG, Kim M, Choi HG. Bidirectional association between gastroesophageal reflux disease and depression: two different nested case-control studies using a national sample cohort [sci rep.]. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):11748. ( 10.1038/s41598-018-29629-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hungin AP, Hill C, Raghunath A. Systematic review: frequency and reasons for consultation for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30(4):331 342. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04047.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Smith GD, Ebrahim S. ‘Mendelian randomization’: can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease? Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32(1):1 22. ( 10.1093/ije/dyg070) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Smith GD, Ebrahim S. Mendelian randomization: prospects, potentials, and limitations. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33(1):30 42. ( 10.1093/ije/dyh132) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Green HD, Beaumont RN, Wood AR.et al. Genetic evidence that higher central adiposity causes gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a Mendelian randomization study. Int J Epidemiol. 2020;49(4):1270 1281. ( 10.1093/ije/dyaa082) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wray NR, Ripke S, Mattheisen M.et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify 44 risk variants and refine the genetic architecture of major depression. Nat Genet. 2018;50(5):668 681. ( 10.1038/s41588-018-0090-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Burgess S, Thompson SG. CRP CHD Genetics Collaboration. Avoiding bias from weak instruments in Mendelian randomization studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(3):755 764. ( 10.1093/ije/dyr036) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. An J, Gharahkhani P, Law MH.et al. Author Correction: gastroesophageal reflux GWAS identifies risk loci that also associate with subsequent severe esophageal diseases. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):5617. ( 10.1038/s41467-019-13526-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Skrivankova VW, Richmond RC, Woolf BAR.et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology using Mendelian randomization: the STROBE-MR statement. JAMA. 2021;326(16):1614 1621. ( 10.1001/jama.2021.18236) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Haycock PC, Burgess S. Consistent estimation in Mendelian randomization with some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet Epidemiol. 2016;40(4):304 314. ( 10.1002/gepi.21965) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(2):512 525. ( 10.1093/ije/dyv080) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hemani G, Zheng J, Elsworth B.et al. The MR-Base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. eLife. 2018;7:e34408. ( 10.7554/eLife.34408) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jansson C, Nordenstedt H, Wallander MA.et al. Severe gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms in relation to anxiety, depression and coping in a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26(5):683 691. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03411.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dent J, El-Serag HB, Wallander MA, Johansson S. Epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2005;54(5):710 717. ( 10.1136/gut.2004.051821) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang R, Wang J, Hu S. Study on the relationship of depression, anxiety, lifestyle and eating habits with the severity of reflux esophagitis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021;21(1):127. ( 10.1186/s12876-021-01717-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Velanovich V, Karmy-Jones R. Psychiatric disorders affect outcomes of antireflux operations for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surg Endosc. 2001;15(2):171 175. ( 10.1007/s004640000318) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kamolz T, Velanovich V. Psychological and emotional aspects of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dis Esophagus. 2002. ;15(3):199 203. ( 10.1046/j.1442-2050.2002.00261.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Johnston BT. Stress and heartburn. J Psychosom Res. 2005;59(6):425 426. ( 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.05.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Choi JM, Yang JI, Kang SJ.et al. Association Between anxiety and depression and gastroesophageal reflux disease: results From a large cross-sectional study. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;24(4):593 602. ( 10.5056/jnm18069) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Avidan B, Sonnenberg A, Giblovich H, Sontag SJ. Reflux symptoms are associated with psychiatric disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15(12):1907 1912. ( 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.01131.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Farré R, De Vos R, Geboes K.et al. Critical role of stress in increased oesophageal mucosa permeability and dilated intercellular spaces. Gut. 2007;56(9):1191 1197. ( 10.1136/gut.2006.113688) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brahm NC, Kelly-Rehm MC. Antidepressant-mediated gastroesophageal reflux disease. Consult Pharm. 2011. April;26(4):274 278. ( 10.4140/TCP.n.2011.274) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Martín-Merino E, Ruigómez A, García Rodríguez LA, Wallander MA, Johansson S. Depression and treatment with antidepressants are associated with the development of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31(10):1132 1140. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04280.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ness-Jensen E, Lagergren J. Tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;31(5):501 508. ( 10.1016/j.bpg.2017.09.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Content of this journal is licensed under a

Content of this journal is licensed under a