Abstract

Study Objectives

The response of sleep depth to CPAP in patients with OSA is unpredictable. The odds-ratio-product (ORP) is a continuous index of sleep depth and wake propensity that distinguishes different sleep depths within sleep stages, and different levels of vigilance during stage wake. When expressed as fractions of time spent in different ORP deciles, nine distinctive patterns are found. Only three of these are associated with OSA. We sought to determine whether sleep depth improves on CPAP exclusively in patients with these three ORP patterns.

Methods

ORP was measured during the diagnostic and therapeutic components of 576 split-night polysomnographic (PSG) studies. ORP architecture in the diagnostic section was classified into one of the nine possible ORP patterns and the changes in sleep architecture were determined on CPAP for each of these patterns. ORP architecture was similarly determined in the first half of 760 full-night diagnostic PSG studies and the changes in the second half were measured to control for differences in sleep architecture between the early and late portions of sleep time in the absence of CPAP.

Results

Frequency of the three ORP patterns increased progressively with the apnea-hypopnea index. Sleep depth improved significantly on CPAP only in the three ORP patterns associated with OSA. Changes in CPAP in the other six patterns, or in full diagnostic PSG studies, were insignificant or paradoxical.

Conclusions

ORP architecture types can identify patients in whom OSA adversely affects sleep and whose sleep is expected to improve on CPAP therapy.

Keywords: odds ratio product response to CPAP sleep architecture

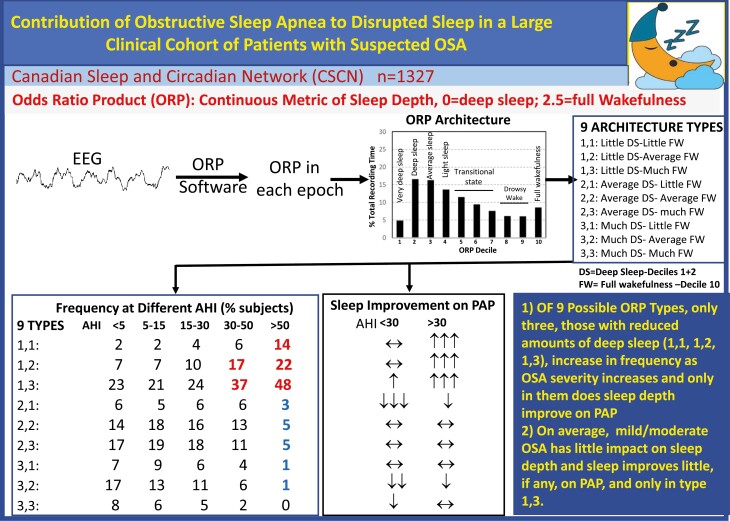

Graphical abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Statement of Significance.

The response of sleep depth to CPAP in patients with OSA cannot be predicted from conventional polysomnography. A new approach to evaluating sleep architecture has recently been introduced using ORP, a continuous index of sleep depth. With this approach, three abnormal patterns were identified that were consistent with a disorder that prevents progression to deep sleep, such as OSA. In this study, we found that improvement of sleep on CPAP occurs only in patients with these three ORP patterns while the response in the remaining six patterns was absent or paradoxical. These findings suggest that patients in whom sleep will not improve on CPAP can be identified from routine sleep studies.

Clinical Trial: This is not a clinical trial.

Introduction

An important objective of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) therapy is to relieve OSA-related sleep disruption and its clinical consequences of excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) and/or insomnia. The clinical relevance of this objective is highlighted by the fact that both EDS and insomnia are associated with significant long-term complications including cognitive decline, cardiovascular disease, accidents, and all-cause mortality [1–13].

OSA is often associated with lighter sleep whether sleep depth is assessed by sleep architecture [14] or by the odds ratio product (ORP), a novel, validated continuous index of sleep depth [15]. OSA is also often associated with excessive wake time [14, 16] and complaints of EDS and insomnia [17–20]. OSA therapy is commonly prescribed when OSA is mild or moderate (AHI < 30hr−1), if symptoms are presently based on the assumption that OSA is responsible for these symptoms. However, sleep symptoms are not specific to OSA and may be caused by other sleep disorders or non-sleep-related co-morbidities [21, 22]. It may be reasonable to assume that symptoms related to OSA-mediated sleep deficiency are more likely to improve with PAP therapy if such therapy relieves the sleep deficiency. At present, there is no way to know in advance if PAP will improve sleep in a given patient. Such advance knowledge may help explain non-adherence to PAP in some patients and, by extension, avoid the disruptive, and expensive efforts to have the patient comply.

ORP is a continuous measure of sleep depth that ranges from zero (indicative of very deep sleep) to 2.5 (indicating full wakefulness) [23–25]. In a direct comparison of ORP vs. delta power, the metric sometimes used to assess sleep depth, it was found that ORP is directly related to sleep depth over ORP’s entire range, whereas delta power is responsive to sleep depth only over the lowest 10% of its physiological range [24]. Above delta power of 300 μV2, further increases are not associated with changes in arousability [24].

Recently, an ORP-based sleep architecture was proposed whereby the percent of epochs within total recording time (TRT) that fall within each decile of the ORP range is calculated, and the 10 values are expressed as a histogram [26]. Nine distinct ORP patterns have been identified that were consistent with different underlying physiologic mechanisms and differed in their associated demographics, clinical phenotypes, and health outcomes [26]. Only three of the 9 patterns were prevalent in patients with OSA. These findings suggested that when sleep is light or excessive wake time exists in patients with OSA, the impairment may be attributed to OSA only in these three ORP types. As such, ORP architecture may help select patients in whom OSA therapy is likely to improve sleep.

We hypothesized that CPAP improves ORP architecture exclusively in the three ORP types prevalent in OSA. We accordingly determined the ORP architecture type from the diagnostic part of split-night PSG studies and evaluated how it changed during the PAP component of the study.

Rationale for the current study

This study was made possible by three distinct capabilities of ORP. First, ORP can distinguish between epochs with full wakefulness (ORP > 2.25), from epochs that meet the conventional definition of wake but contain sleep features (drowsy wake; ORP 1.75–2.25) [15, 23, 26]. Intuitively, large amounts of full wakefulness would suggest low sleep pressure (e.g. hyperarousal, poor sleep hygiene, circadian misalignment, etc.) [26], whereas large amounts of drowsy wake would suggest high sleep pressure by sleep-disrupting factors (e.g. OSA upon falling asleep, other sources of arousal stimuli, etc.) that interfere with progression to sleep. This inference is supported by the fact that ESS is inversely related to time in full wakefulness [26]. Furthermore, average ORPWAKE, which is determined by the relative time contributions of full and drowsy wakefulness, predicts sleepiness, and poor sleep quality [27].

Second, ORP can distinguish epochs with different sleep depths within NREM stage 2 [26], thereby providing an objective index of sleep depth within the most prevalent stage of sleep.

Third, ORP can identify deep sleep independent of the large, slow (≤2Hz) delta waves because it relies on power in the higher frequency range (>2.3 Hz) of delta power [23], which is more sensitive to differences in sleep depth than the large/slow delta waves [23, 24]. Thus, the requirement that delta waves occupy a specified fraction of the epoch [28], a visually difficult and unreliable task [29], is obviated. With greater confidence in the estimated amount of deep sleep, one can make logical inferences about reasons for this value to be high or low. Thus, too little deep sleep may result from low sleep pressure (advanced age, hyperarousal, etc.) or from a disorder that interferes with progression to deep sleep (e.g. OSA, arousal stimuli from other sources) whereas high values suggest high sleep pressure (e.g. sleep loss) [26]. Again, this inference is supported by the fact that low levels of ORP-determined deep sleep are associated with reduced quality of life [26] and occur with greater frequency as OSA severity increases [26].

Dividing the range of deep sleep into three ranges (low, average, and high) and the amount of full wakefulness also into three ranges, results in nine non-overlapping patterns (diagnostic panels, Figure 1) that have different putative underlying mechanisms [26]. Thus, pattern 1,1, with little amounts in both deep sleep and full wakefulness (Figure 1), would suggest a disorder that interferes with sleep progression and, in the process, results in increased sleep pressure, hence little time in full wakefulness [26]. Such a pattern would be expected in a patient with OSA whose sleep is compromised by the disorder and is, as a result, sleepy. By contrast, type 1,3, with similarly reduced amounts of deep sleep, but a large amount of full wakefulness (Figure 1), would be expected in patients with generally low sleep pressure throughout the night. Although low sleep pressure may be independent of OSA and occurs frequently without OSA [26], patients with light sleep are more prone to OSA [30, 31] and many patients with this type have comorbid OSA [26]. Patients with type 1,2 are intermediate and, as in type 1,1, their reduced amount of deep sleep is not likely due to low sleep pressure in view of the normal amount of full wakefulness. In the other six ORP types, the amount of deep sleep is average or increased (Figure 1), and ORP architecture is not different from the types found in participants with no OSA [26], making it unlikely that OSA is associated with poor sleep.

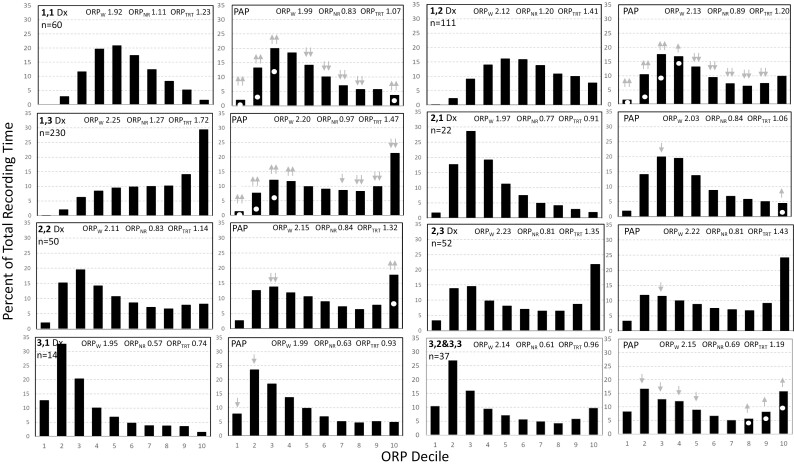

Figure 1.

Odds Ratio Product (ORP) histograms of the different ORP types during the diagnostic (Dx, left panel in each pair) and the positive airway pressure (PAP) sections of split studies. The two-digit number in the top left corner of the diagnostic panel is the ORP type with the first digit reflecting the % of the time in deep sleep (Sum of deciles 1 and 2; 1 = < 10.2%, 2 = between 10.2% and 28.5%, and 3 = > 28.5%) and the second digit reflecting the % of time spent in full wakefulness (decile 10; 1 ≤ 3.4%, 2 = 3.4%–12.5%, 3 ≥ 12.5%). n is the number of participants in each ORP type. White dots in the PAP panels indicate the values found in the diagnostic (left) panel. Gray arrows indicate a significant difference from the corresponding decile in the diagnostic section with upgoing arrows signifying a significant increase, and vice versa. One arrow, p < 0.05. Two arrows, p < 0.001. There were few patients in type 3,3 (n = 10) and their responses were similar to those with type 3,2. Accordingly, the two types were combined (bottom right of figure). Note that in types 1,1, 1,2, and 1,3, the histogram shifts to the left, indicating deeper sleep, while it does not change or shift to the right in the other types.

Methods

This study utilized the following pre-existing datasets

576 split-night polysomnograms (PSGs) from three academic Canadian centers (Universities of Calgary [n = 251], Saskatchewan [n = 144], and Manitoba [n = 181]).

760 full-night diagnostic PSGs from four academic Canadian centers (Universities of British Columbia [n = 486], Saskatchewan [n = 152], McGill [n = 87], and Laval [n = 35]).

The studies were approved by the Research Ethics Boards of the respective universities. The types of sleep studies used by individual sleep centers reflect their practice patterns. In some centers, patients evidencing severe OSA in the first part of the diagnostic PSG are placed on PAP in the latter part of the study (split-night study), whereas in others a full-night diagnostic PSG is completed in all patients before prescribing CPAP therapy.

PSG records included the standard montage with 4–6 EEG channels (central and occipital in all), electrooculograms, chin EMG, pulse oximetry (SpO2), chest and abdomen bands, nasal cannula airflow, audio, and EKG. Additional information included age, gender, body mass index (BMI), Epworth Sleepiness scale (ESS), and Insomnia severity index (ISI) in most studies.

PSG analyses

PSG records were de-identified and sent to MY for digital analysis. Digital analysis generated the ORP values [23, 26] as well as conventional scoring indices (sleep stages, AHI, etc. The scoring algorithm for measuring conventional metrics was previously validated against the scoring of ten academic technologists [32]. Intraclass correlation coefficient for the relation between autoscoring and the average of 10 scorers was 0.96 for NREM AHI and 0.95 for REM AHI using the primary AASM hypopnea criteria at the time (30% reduction in amplitude plus a 4% decrease in O2 hemoglobin saturation) and 0.91 and 0.92 for NREM and REM AHI using the alternate hypopnea criteria at the time (3% desaturation or arousal). Severity of OSA was designated mild if AHI was 5–15 hr−1, moderate if 15–30 hr−1, severe if 30–50 hr−1, and very severe if > 50 hr−1.

The method of measuring ORP has been described in detail previously [23]. ORP was determined from two central EEG derivations in consecutive 3-sec epochs throughout the PSG. Artifact detection algorithms identified poor-quality 3-sec epochs, and these were excluded from the analysis. Results of the C3 and C4 ORP values in each 3-sec epoch were averaged, and the 10 ORP values within each 30-sec epoch were averaged to produce a single ORP value for each 30-sec epoch.

Average ORP in stages wake (ORPWAKE), NREM (ORPNREM), and total recording time (ORPTRT) were calculated separately in the diagnostic and PAP titration sections of split-night studies and the first and second halves of full-diagnostic studies. For ORP architecture the number of 30-sec epochs within each ORP decile was calculated and expressed as a percent of the total number of epochs [26] in the relevant section. ORP-architecture type was expressed as a 2-digit number (e.g. 1,1, 2,3, etc.) based on % epochs in deep sleep (ORP < 0.50; first digit) and percent in full wakefulness (ORP > 2.25; the second digit). As described previously [26], the first digit is assigned 1 if % epochs in deep sleep are < 10.2%, 2 if 10.2 to 28.5%, and 3 if > 28.5%. The second digit is assigned 1 if % epochs in full wakefulness are < 3.4%, 2 if 3.4 to 12.5%, and 3 if > 12.5%. These thresholds represented the 25th and 75th percentiles of the distribution of % epochs in deep sleep and full wakefulness in the SHHS [26]. Thus, ORP type 2,1 indicates that the patient’s deep sleep was in the interquartile range of this value in the community while the amount in full wakefulness was in the lowest quartile. With this threshold-defined approach, there is no overlap between types and a patient’s sleep data can belong to only one type.

Statistical analyses

Split-night PSG studies were used to determine the ORP types at different levels of OSA severity (AHI) in the diagnostic section and changes in ORPWAKE, ORPNREM, and ORPTRT with PAP in each ORP type. Split-night studies were sorted by AHI in the diagnostic section and divided into mild (AHI 5–15hr−1), moderate (AHI 15–30 hr−1), severe (AHI 30–50 hr−1), and very severe (AHI > 50 hr−1). Distribution of the nine ORP types in each group was determined and differences in distribution between groups were assessed by the Chi-square test. The studies were then sorted by ORP type and differences in ORPWAKE, ORPNREM, and ORPTRT between the diagnostic and PAP sections within each type were assessed by paired t-test.

We also determined the variables associated with different PAP-associated changes in ORP values within each ORP type. Multiple linear regression with backward elimination was performed between the individual changes in each ORP variable, as dependent variable, and age, gender, BMI, AHI, arousal index, ORPWAKE, ORPNREM, % of times in deep sleep (ORP < 0.5), and in full wakefulness (ORP > 2.25) in the diagnostic section as independent variables. Elimination continued until p was less than 0.10 for all independent variables.

The same analyses were applied to the full-night diagnostic studies except for use of the 2nd half of the PSG instead of the PAP section used in the split-night studies. Comparisons between ORP values in the first and second halves of the PSG established the expected differences between early and late ORP values in the absence of PAP therapy and served as “control” for the changes with PAP observed in split-night studies.

Results

Demographic and PSG data in the two clinical datasets are given in Table 1. Participants who underwent full-night diagnostic studies were younger, lighter, and less sleepy, than those with split-night studies and had less severe OSA than in the diagnostic part of split-night studies. On PAP (split-night studies) AHI and arousal index decreased as expected, while changes in conventional sleep architecture, while significant, were small or expected (e.g. increased REM time in the second half or decrease in N1 time as arousals decreased [26].

Table 1.

Demographic and polysomnography data

| Variable | Split studies | Full diagnostic studies | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic | PAP | First half | Second half | |

| Number | 576 | 760 | ||

| Age (years) | 55.8 (12.8) | 52.2 (14.0)++ | ||

| Gender (F/M) | 295/281 | 384/376 | ||

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 39.4 (8.7) | 29.8 (6.5)++ | ||

| Epworth sleepiness scale | 10.2 (5.3) | 8.5 (5.0)++ | ||

| Insomnia severity index | 13.3 (6.1) | 12.5 (5.4) | ||

| Total recording time (min) | 178 (67) | 237 (71)** | 200 (38)++ | 233 (34)** |

| Total sleep time (min) | 127 (55) | 173 (75)** | 138 (50)++ | 179 (48)** |

| Sleep efficiency (%) | 68.7 (18.5) | 71 (19.7)* | 69.1 (20.6) | 77.0 (17.1)** |

| Stage N1 (%TRT) | 18.1 (12.5) | 10.4 (6.8)** | 11.7 (8.2)++ | 15.6 (9.5)** |

| Stage N2 (%TRT) | 38.1 (15.3) | 37.8 (12.8) | 41.7 (16.8)++ | 46.4 (14.4)** |

| Stage N3 (%TRT) | 7.6 (11.0) | 6.0 (9.1)* | 11.8 (13.7)++ | 4.7 (8.0)** |

| Stage REM (%TRT) | 4.4 (6.3) | 17.4 (12.3)** | 3.3 (5.4)++ | 9.7 (10.2)** |

| Arousal/awakening index (hr−1) | 49.7 (26.2) | 26.9 (15.8)** | NA | NA |

| PLM index (hr−1) | 18.0 (27.2) | 12.6 (25.5)** | NA | NA |

| Apnea hypopnea Index (hr−1) | 58.9 (34.7) | 16.3 (15.6)** | 19.6 (20.3)++ | 21.0 (19.2)* |

Values are mean (SD); PAP, positive airway pressure; PLM, periodic limb movements; *, **, significantly different from the first portion of the study by paired t.test (p < 0.01, p < 0.0001); ++, significantly different from the diagnostic part of split studies by t-test (p < 0.0001).

ORP types in different OSA severity categories

The frequency distribution of the nine ORP types at four levels of AHI in the two types of studies is shown in Table 2. All split-night PSGs had some degree of OSA, whereas 133 full-night diagnostic PSGs had no OSA (AHI < 5) (Table 2). Frequency distribution of different ORP types in mild and moderate OSA was not different from the no-OSA group (χ2p > 0.57 and > 0.78, respectively). In both types of study, frequency distribution in the severe and very severe groups was significantly different from the “no-OSA” group (p < 0.0001 in both groups), primarily because of increased frequency of ORP types 1,1, 1,2, and 1,3 (Table 2). In very severe OSA these three types accounted for 85% of all patients. There were no significant differences between the two types of study in distribution within any OSA severity group (Table 2; p > 0.20 in all four comparisons).

Table 2.

Distribution of ORP Types in Different OSA Severity Categories

| ORP type | Diagnostic part of split studies | First half of full night studies | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AHI (SD) | Mild | Mod. | Sev.** | Very Sev.** | AHI (SD) | No OSA | Mild | Mod. | Sev.* | Very Sev.* | |

| 1,1 | 80.6 (31.9) | 2 (4) | 3 (3) | 6 (5) | 49 (16) | 30.0 (27.7) | 2 (2) | 4 (1) | 7 (4) | 5 (6) | 4 (6) |

| 1,2 | 71.0 (36.8) | 3 (7) | 14 (13) | 22 (19) | 72 (23) | 21.0 (21.5) | 9 (7) | 22 (7) | 15 (9) | 11 (13) | 10 (16) |

| 1,3 | 62.9 (32.9) | 14 (33) | 28 (26) | 45 (39) | 143 (46) | 25.9 (24.7) | 31 (23) | 57 (19) | 39 (23) | 28 (33) | 36 (56) |

| 2,1 | 32.7 (25.3) | 3 (7) | 6 (6) | 5 (4) | 8 (3) | 16.2 (16.0) | 8 (6) | 15 (5) | 11 (6) | 6 (7) | 3 (5) |

| 2,2 | 44.8 (29.8) | 5 (12) | 16 (15) | 13 (11) | 16 (5) | 15.1 (12.9) | 18 (14) | 55 (19) | 29 (17) | 13 (15) | 4 (6) |

| 2,3 | 36.6 (25.1) | 8 (19) | 19 (17) | 11 (10) | 14 (5) | 16.5 (15.4) | 23 (17) | 57 (19) | 32 (18) | 10 (12) | 5 (8) |

| 3,1 | 37.4 (18.4) | 0 (0) | 6 (6) | 5 (4) | 3 (1) | 13.4 (12.4) | 9 (7) | 30 (10) | 11 (6) | 3 (4) | 1 (2) |

| 3,2 | 31.6 (22.7) | 5 (12) | 12 (11) | 6 (5) | 4 (1) | 14.0 (11.5) | 22 (17) | 40 (13) | 20 (12) | 6 (7) | 1 (2) |

| 3,3 | 25.0 (18.6 | 2 (5) | 5 (5) | 2 (2) | 1 (0) | 9.9 (6.6) | 11 (8) | 17 (6) | 9 (5) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Total # | 58.9 (34.7) | 42 | 109 | 115 | 310 | 19.6 (20.3) | 133 | 297 | 173 | 84 | 64 |

Other than for the AHI column, which reports mean ± SD of AHI, the numbers in each AHI category are numbers of participants (% of total participants in the OSA category). ORP, odds ratio product; *, **, significantly different from “No OSA” by Chi-square with p < 0.05 and < 0.0001, respectively.

Response to PAP in split studies

The ORP histograms of the different ORP types and their change in PAP in the split-night studies are shown in Figure 1. Sleep improved in types 1,1, 1,2, and 1,3, as evident by greater fractions of TRT spent in deep sleep (ORP < 0.5, deciles 1 and 2) and less fractions in light and transitional sleep (ORP 1.0–1.75; gray arrows, Figure 1). In type 1,1, the fraction spent in full wakefulness (ORP > 2.25; decile 10) increased while in type 1,3 it decreased but remained quite high (>20% TRT; Figure 1). In the other six ORP types, changes, if any, were in the direction of less deep sleep and more time in full wakefulness.

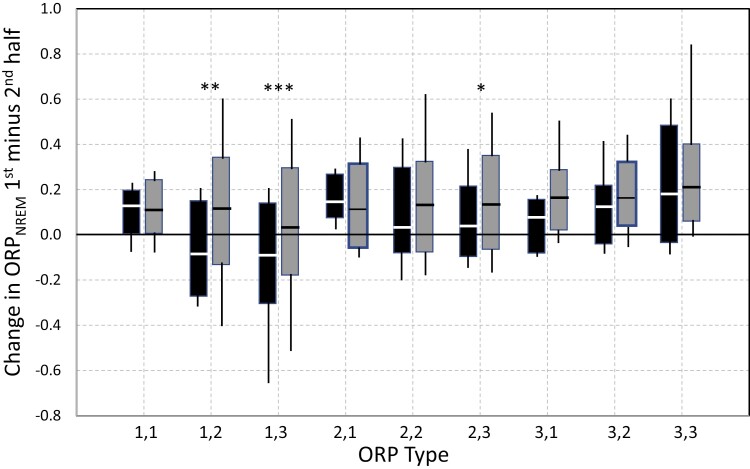

The range of changes in ORPNREM on PAP in patients with different ORP types is shown in Figure 2, A. In types 1,1, 1,2, and 1,3, sleep depth improved on PAP (ORPNREM decreased) in the vast majority of patients (85%, 86%, and 87%, respectively). ORPNREM decreased by > 0.20 units in the majority of patients (65%, 63%, and 57%, respectively), while in a quarter (23%, 26%, and 25%) it decreased by >0.50 units. By contrast, in the other six types, average ORP was similar or higher on PAP and ORPNREM decreased by more than 0.2 units in a small minority (19 of 172 patients, 12%), and by > 0.4 units in only four patients (2%). For reference, the difference between the average ORP in stages N1 and N3 are only 0.6 units [23].

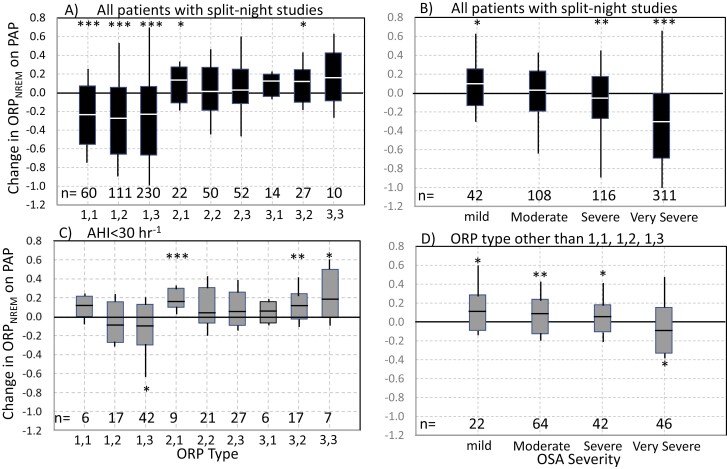

Figure 2.

(A) Range of changes in ORPNREM on positive airway pressure (PAP) in the different odds ratio product (ORP) types in all split studies. Solid rectangles define the 10th and 90th percentiles of the range, white line is the median, and the lines (not whiskers are) extend to the maximum and minimum values. (B) Similar plot as panel A but for different levels of OSA severity. (C) Similar plot as in panel A but only in patients with mild/moderate OSA (apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) < 30hr−1). (D) Similar plot to panel B but only for patients with ORP types other than 1,1, 1,2, and 1,3. *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.001, ***, p < 0.00001

The change in ORPNREM on PAP at different levels of OSA severity is shown in Figure 2, B. On average, change in sleep depth on PAP was very small up to severe OSA (paradoxical in mild/moderate OSA). ORPNREM reliably decreased only in very severe OSA (AHI > 50hr−1), where sleep depth improved on PAP in 90% of patients (Figure 2, B). ORP type in very severe OSA was one of the three responsive types in 85% of patients (Table 2).

The change in ORPNREM on PAP in patients with AHI < 30 hr−1 was, on average, paradoxical (lighter sleep) or not significant except in type 1,3 where there was a small improvement (−0.09 on average; p < 0.01; Figure 2, C). When ORP type was other than the three responsive types (1,1, 1,2, and 1,3) the change in ORPNREM on PAP in patients with AHI < 50 hr−1 was, on average, paradoxical (lighter sleep; Figure 2, D).

The variables associated with better response in each of the three responsive ORP types are given in Table 3. The significant covariates differed between the three ORP types. AHI was a significant covariate in all three ORP types. Other variables that were associated with better response in at least one ORP type included the arousal-awakening index, ORPWAKE, ORPNREM, and percent of the time in deep sleep (ORP < 0.5) and in full wakefulness (ORP > 2.25; Table 3). Importantly, ESS was not significantly associated with the ORPNREM response in any of the types.

Table 3.

Covariates associated with improvement in sleep depth on PAP*

| Variables | Type 1,1 | Type 1,2 | Type 1,3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of observations | 60 | 111 | 224 |

| Intercept | 0.060 (NS) | 0.825 (p = 0.04) | −0.847 (p = 0.07) |

| Age (years) | 0.004 (p = 0.004) | ||

| Gender (Male = 0, Female = 1) | −0.073 (p = 0.05) | ||

| BMI (Kg/M2) | 0.004 (p = 0.02) | ||

| AHI (hr−1) | −0.003 (p = 0.0002) | −0.002 (p = 0.01) | −0.004 (p < 0.00001) |

| Arousal/Awakening index (hr−1) | −0.003 (p = 0.004) | −0.005 (p < 0.00001) | |

| ORPWAKE | 0.285 (p = 0.02) | −0.459 (p = 0.01) | 0.558 (p = 0.01) |

| ORPNREM | −0.372 (p = 0.01) | −0.408 (p < 0.00001) | |

| ORP < 0.5 (% TRT) | 0.022 (p = 0.004) | ||

| ORP > 2.25 (%TRT) | −0.038 (p = 0.09) | −0.004 (p = 0.01) | |

| Epworth sleepiness scale | |||

| Overall significance | r 2 = 0.65 | r 2 = 0.57 | r 2 = 0.47 |

*Results are from split studies; Values are the coefficients with their level of significance; PAP, positive airway pressure; ORP, odds ratio product; AHI, apnea-hypopnea index; TRT, total recording time; BMI, body mass index.

ORP in the first and second parts of PSGs with (split-night studies) and without PAP

ORP values in the diagnostic parts of split-night studies and the first half of full-night diagnostic studies were similar; any significant differences (3 of 27 comparisons) were small (<0.1)(Figure 3, A, C, and E). As expected, ORPWAKE was lowest in ORP types with little time in full wakefulness (second digit = 1), and vice versa (Panel 3A), while ORPNREM was highest (lightest sleep) when time in deep sleep was lowest (first digit = 1 (Panel 3C).

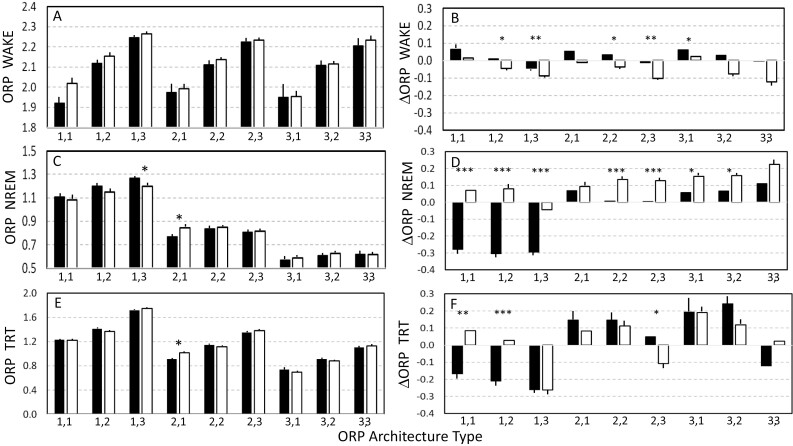

Figure 3.

Left panels: Comparison of odds ratio product (ORP) values in the diagnostic part of split-night studies (solid bars) and in the first half of full-night diagnostic studies. ORP values in any given ORP type were quite similar whether the study was split-night or full-diagnostic except in three comparisons (asterisks). Right panels: comparison of changes in ORP values on PAP in split studies (solid bars) and their changes in the second half of full-diagnostic studies (open bars). In all panels bars are SEM and asterisks indicate significant differences. *. **, ***, p < 0.005, p < 0.001, p < 0.0001, respectively. In the right panels, SEM bars are inserted only if the change is significantly different from zero. NREM, non-rapid-eye-movement sleep. TRT, total recording time.

The changes in ORP on PAP in split-night studies are compared with ORP changes in the second half of full-night diagnostic studies in Figure 3, B, D, and F. The difference between the two values represents the effect of PAP. Changes in ORPWAKE were small regardless of ORP type or type of study (Panel B). In 5 of 9 ORP types, there was a significant difference between changes in ORPWAKE in the two PSG types. These differences were, however, small.

In full-night diagnostic studies, ORPNREM was higher in the second half, indicating lighter sleep, except in ORP type 1,3 (Open bars, Figure 3, D). By contrast, and as previously shown in Figure 2, ORPNREM was substantially lower on PAP in types 1,1, 1,2, and 1,3 (solid bars, Figure 3, D). As a result, the difference between split-night and full diagnostic studies in these three types was large and highly significant (p < 1E-8). In the remaining six types ORPNREM did not change significantly on PAP (see also Figure 2) whereas it increased in the diagnostic studies. There were significant differences in responses on and off PAP, but these were much smaller than in types 1,1, 1,2, and 1,3 (Figure 3, D).

Changes in ORPTRT (Figure 3, F) were unexpected. In types 1,1 and 1,2 the changes were similar to those of ORPNREM with a highly significant effect of PAP (Figure 3, F). However, in type 1,3 ORPTRT decreased to the same extent in full-night diagnostics studies, indicating that improvement in split-night studies was unrelated to PAP (Figure 3, F). The reason for this finding was that SE improved substantially in the second half of both types of study (53.9 ± 16.4% to 64.3 ± 19.5% in split-night studies and 69.1 ± 20.3% to 77.0 ± 17.8% in diagnostic studies). Consequently, in both study types, the second half included fewer wake epochs with high ORP, resulting in a lower average. In five of the remaining six ORP types, ORPTRT increased in the latter half whether PAP was applied or not. In type 2,3, ORPTRT decreased only in the full diagnostic studies as it did in type 1,3 and for the same reason (increased SE) resulting in a marginally significant difference from split-night studies. Thus, PAP seems to be effective in improving ORPTRT only in ORP types 1,1 and 1,2.

The changes in ORPNREM with and without PAP in patients with AHI < 30hr−1 are shown in Figure 4. In full diagnostic studies (gray bars) changes in all ORP types were in the direction of lighter sleep in the second half of the PSG. In split-night studies, the changes were also in the direction of lighter sleep in all ORP types except 1,2 and 1,3 where average ORPNREM decreased, and the decrease was significantly below the change in full diagnostic studies (p < 0.001). Accordingly, in patients with mild/moderate OSA, PAP improves NREM sleep only in these two types, but the improvement is much smaller than in more severe OSA (cf. Figure 3).

Figure 4.

Changes in ORPNREM with (black bars; split studies) and without (full-diagnostic studies) positive airway pressure (PAP) in patients with an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) < 30hr−1. *. **, ***, p < 0.01, p < 0.001, p < 0.001, respectively.

Self-reported complaints in different ORP types

There were 1276 ESS measurements and 1057 ISI measurements. Average ESS in the entire cohort was 9.2 ± 5.2 with 579 patients having ESS ≥ 10 (45.4%) and 126 (9.9%) having ESS ≥ 17 (Table 4). Average ISI was 12.8 ± 5.7 with 420 patients (39.7%) having ISI ≥ 15 and 67 patients (6.3%) having ISI ≥ 22 (Table 4). Of patients who had both indices (n = 1057), there were 242 (22.9%) with ESS ≥ 10 and ISI ≥ 15.

Table 4.

Self-reported sleep complaints in different ORP types

| Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) | Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORP type | n (%) | Ave (SD) | % ≥ 10 | % ≥ 17 | n (%) | Ave (SD) | % ≥ 15 | % ≥ 22 |

| 1,1 | 84 (6.6) | 11.3 (5.4) | 67.9 | 15.5 | 64 (6.1) | 14.0 (6.1) | 54.7 | 7.8 |

| 1,2 | 225 (17.6) | 10.6 (5.4) | 57.6 | 15.2 | 180 (17.0) | 13.6 (5.6) | 44.4 | 8.9 |

| 1,3 | 369 (28.9) | 8.8 (5.0) | 42.4 | 10.1 | 284 (26.9) | 13.3 (5.8) | 42.6 | 6.3 |

| 2,1 | 72 (5.6) | 9.3 (5.2) | 46.5 | 11.3 | 62 (5.9) | 11.8 (5.5) | 32.3 | 8.1 |

| 2,2 | 179 (14.0) | 8.9 (4.6) | 39.7 | 5.0 | 158 (14.9) | 12.8 (5.2) | 36.7 | 5.7 |

| 2,3 | 173 (13.6) | 7.9 (4.9) | 35.3 | 5.2 | 152 (14.4) | 11.7 (5.6) | 35.5 | 3.9 |

| 3,1 | 65 (5.1) | 8.0 (5.4) | 29.7 | 7.8 | 56 (5.3) | 11.1 (5.7) | 28.6 | 3.6 |

| 3,2 | 87 (6.8) | 9.1 (5.1) | 47.1 | 8.0 | 80 (7.6) | 12.0 (5.9) | 36.3 | 6.3 |

| 3,3 | 22 (1.7) | 10.2 (5.2) | 45.5 | 18.2 | 21 (2.0) | 12.1 (5.3) | 33.3 | 4.8 |

| ALL Excl. | 1276 | 9.2 (5.2)* | 45.4%## | 9.9%# | 1057 | 12.8 (5.7)$ | 39.7% | 6.3% |

| 1,1, 1,2, 1,3 | 598 | 8.7 (5.0) | 39.5% | 7.0% | 529 | 12.1 (5.4) | 34.80% | 5.30% |

*Signifigant differences between different ORP types by one-way analysis of variance (p = 1E-7). #, ##, significant.

differences between ORP types in frequency of ESS ≥ 10 (p = 1E-7)) and ESS ≥ 17 (p = 6E-3) by Chi square test.

$Signifigant differences between different ORP types by one-way analysis of variance (p < 0.003).

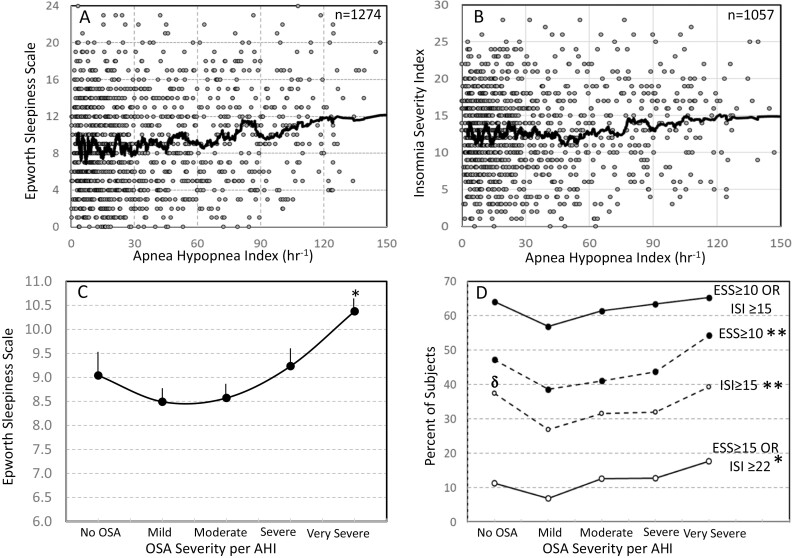

Figure 5, A shows the relationship between AHI and ESS in 1274 patients with available ESS and Figure 4, B is a similar plot for ISI in 1057 patients with available ISI. In both cases, average ESS and ISI increased little until OSA was very severe (AHI > 50 hr−1). Figure 5, C shows average ESS at different OSA severity levels. This relationship was U-shaped, with the lowest ESS seen in patients with mild/moderate OSA. ESS was significantly higher in very severe OSA versus mild (p < E-6) and moderate (p < E-5) OSA, but not vs. No OSA. No other significant differences were found.

Figure 5.

(A) Scatter plot of Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) vs. apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) in the current study. Each dot is a patient. Heavy line is a 50-point moving average. (B) Similar plot to panel A but for the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI). (C) Average Epworth Sleepiness Scale at different OSA severities. No OSA: AHI < 5 hr−1; Mild: AHI 5–15 hr−1; Moderate: AHI 15–30 hr−1; Severe: AHI30–50 hr−1; Very Severe: AHI > 50 hr−1. Number of participants ranged from 146 (No OSA) to 363 (very severe). Bars are SEM. There were significant differences among OSA levels by ANOVA (p < 0.00001);*, significantly different from mild and moderate OSA by t. test (p < 0.00001). D) Percent of participants with different ESS and ISI thresholds (see legend). *, **, significant differences between different levels of OSA severity by Chitest, p < 0.05, p < 0.002, respectively. δ, significantly higher than mild OSA by Chitest (p < 0.0001).

Figure 5, D shows the percentage of patients that met different ESS and ISI thresholds at different OSA severities. Percent of patients in whom at least one of the two indices (ESS or ISI) was abnormal (ESS ≥ 10 and/or ISI ≥ 15) was 64.1% in the no-OSA group and changed little as OSA severity increased (top solid line). The bottom line shows that in 11.3% of patients with no OSA at least one of the two indices was highly abnormal (ESS ≥ 17 and/or ISI ≥ 22) and the percentage increased to 17.6% in the most severe OSA. The middle two lines show the percent of patients with ESS ≥ 10 and with ISI ≥ 15 at different levels of OSA severity. There were significant differences by one-way ANOVA in ESS among patients with different levels of OSA severity for ESS ≥ 10, ISI ≥ 15, and ESS ≥ 15, or ISI ≥ 22. The results paralleled those of average ESS (panel C), further showing the tendency of ESS and ISI to be higher in patients with no OSA than in patients with mild to severe OSA.

Table 4, left, shows that participants with ORP types 1,1 and 1,2 had the highest average ESS and highest % of participants with ESS ≥ 10 and ≥ 17. In these two types, average ESS was higher than the average of the entire cohort (p = 0.0004 and p = 0.0003, respectively) while there were no differences among the other seven types (p > 0.15). There were significant differences among ORP types in frequency of ESS values ≥ 10 and ≥ 17 (p = 1E-7 and 6E-3, respectively) with the frequency of patients having ESS ≥ 10 exceeding 65% in type 1,1 and > 55% in type 1,2 (Table 4, left).

Average ISI in types 1,1, 1,2, and 1,3 (14.0 ± 6.1, 13.6 ± 5.6, and 13.3 ± 5.8, respectively) were significantly higher than average ISI in the other six types (12.1 ± 5.4) (p = 0.004, 0.0005, and 0.004, respectively) and there were no differences in average ISI among the other six types by one-way ANOVA (p = 0.81).

Discussion

This is the first study to explore whether in a given individual with OSA the likelihood of sleep to improve on CPAP can be estimated from diagnostic sleep studies. The main conclusions are (1) An important sleep improvement can be strongly expected only if ORP architecture belongs to three of nine possible ORP architecture types, and (2) The impact of OSA on ORP architecture in mild/moderate OSA is minimal and sleep in these patients improves minimally on CPAP and only in two of nine ORP types.

Response of ORP architecture to PAP

The current study has demonstrated that only in three of nine ORP patterns (patterns 1,1, 1,2, and 1,3) does sleep depth increase on PAP (Figures 1 and 2). These responsive types are less common in mild/moderate OSA (Table 2) and their response to PAP is markedly attenuated or reversed (Figure 4) such that, on average, sleep improvement on PAP is not to be expected in such patients (Figure 2, B). Improvement was substantial and highly significant only in very severe OSA (Figure 2, B). It must be noted that 85% of patients with very severe OSA (AHI > 50hr−1) belonged to the three responsive ORP types (Table 2). Thus, the advantage of using ORP type over AHI to predict the impact of OSA on sleep depth is quite evident, particularly in mild OSA.

It is important to put these ORP changes in some physiological, potentially clinical context. In a large community study (SHHS) ORP in NREM sleep averaged 0.83, 0.85, and 0.93 in mild, moderate, and severe OSA, respectively, while it averaged 0.81 in participants with no OSA [15]. Thus, a reduction in ORPNREM of 0.12 is comparable, all else being the same, to the difference in sleep depth between that associated with severe OSA and no OSA.

The arousal index was a significant independent variable in types 1,1 and 1,2 (Table 3). Thus, for a given AHI, patients with more frequent arousals sustain a better response. Lighter NREM sleep was associated with better response but only in types 1,1 and 1,3 (Table 3) while the amount of deep sleep was inversely related to improvement in types 1,2. Thus, the use of the equations in Table 3 may help narrow the range of expected improvement on PAP.

The increased frequency of patterns 1,1 and 1,2 in severe and very severe OSA (Table 2), confirms earlier findings in several hundred SHHS participants [26]. The normalization of the patterns on PAP (Figure 1) further confirms that patterns 1,1 and 1,2 result from a disorder that interferes with progression to deeper levels of sleep such as severe OSA (see Rationale). However, these two patterns also occur, but with less frequency, in participants with no OSA ([26], also Table 2) Our findings in OSA patients, therefore, suggest that, when seen without OSA, and particularly if associated with sleep symptoms, these two patterns may warrant exploration of non-OSA sleep disrupting disorders (e.g. PLMs, somatic pain, and other sources of sleep disruption). We have also confirmed earlier findings in several hundred SHHS participants [26] that the distribution of ORP patterns in mild and moderate OSA is not significantly different from patterns in participants with no OSA (Table 2). This, and the infrequent sleep improvement on PAP in such cases (Figure 2, C), suggest that the underlying disorder in these cases (types 1,1 and 1,2 with AHI < 30 hr−1) was not predominantly driven by OSA.

Type 1,3 presents a special case in that the reduced amount of deep sleep is associated with excessive time in full wakefulness. This pattern suggests a state of low sleep pressure throughout the PSG (see Rationale). This pattern occurs very frequently with and without OSA in clinical cohorts (Table 2). We have shown that sleep depth improves significantly in this pattern (Figures 1–3) even when OSA severity is mild/moderate (Figure 2, C). Accordingly, the current results indicate that when this pattern is associated with OSA the poor sleep depth is, in part, due to OSA. Importantly, PAP was associated with a reduction, but not complete correction, of the excessive time in full wakefulness (Figure 1).

Comparison between split and full-diagnostic studies

This analysis allowed us to determine whether the changes observed on PAP in split-night studies could be explained by the different times of night the diagnostic and PAP data were collected. As seen in Figure 3, changes in ORP values in the second half of full diagnostic studies in types 1,1, 1,2, and 1,3 were minimal or opposite in direction to changes in PAP, confirming that ORP reduction on PAP in these three patterns was PAP-related. In four of the last six types (2,2, 2,3, 3,1, and 3,2) ORPNREM increased (lighter sleep) in the second half of full-diagnostic studies but not on PAP (Figure 2). However, the differences between split and no-PAP studies while statistically significant were small in all cases.

In type 1,3 ORPTRT decreased in the full-night diagnostic studies to the same extent as it did on PAP (Figure 3). This resulted from an increase in sleep efficiency in both study types. It would thus appear that in this type (1,3) there is less wake time in the second half even without PAP such that, as predicted from a previous study [16], the decrease in wake time on PAP is likely not PAP-related.

Self-reported complaints in different ORP types

The current study clearly demonstrates that the impact of OSA on ESS and ISI is very small relative to the variability of these indices in patients with no OSA (Figure 5, A and B). Furthermore, average ESS and ISI increased with OSA severity only beyond AHI of ≈ 45 hr−1 (Figure 5, A and B) and only when ORP type was 1,1 or 1,2 (Table 4). These findings, along with the substantial improvement in sleep depth on PAP in these two types (Figure 2), suggest that types 1,1 and 1,2 are specific indicators that sleep will improve with OSA therapy.

Interestingly, there was a tendency for these indices to be higher in patients with no OSA than in those with mild-severe OSA (Figure 5, C and D). The reason for this is not clear. One possible explanation is that many patients with excessive sleepiness or insomnia, unrelated to OSA, are referred for sleep studies to rule out OSA because of associated snoring or witnessed apneas that ultimately turn out to be insufficient for the diagnosis of OSA (i.e. AHI < 5 hr−1).

Limitations

Split-night studies may be criticized on three grounds: first, because sleep changes across the night, it is difficult to attribute differences in sleep between the earlier diagnostic part and the later therapeutic part of the PSG to the impact of PAP. This limitation was addressed here by comparing changes in PAP in split-night studies with the changes that occur in the second part of full-night diagnostic studies (Figure 3). This did not alter the main conclusions of the study.

Second, data from both the diagnostic and therapeutic parts of the PSG are collected over a few hours and may not be representative of PAP’s effect when used repeatedly and throughout the night. This limitation was not dealt with here. However, full-night titration on a separate night is not without similar limitations in view of the substantial night-to-night variability in OSA severity [33, 34].

Third, because a cumbersome device is introduced for the first time to the patient, with potential negative impact on sleep, CPAP titration studies, whether split or full-night, may not represent the changes that might occur with long-term use of CPAP. This is unlikely in view of a recent study that found that ORPNREM decreased from 0.69 ± 0.24 in the diagnostic study to 0.57 ± 0.22 on CPAP after 3–4 weeks of CPAP therapy with good adherence [35]. This is to be compared with a change from 1.05 ± 0.32 to 0.87 ± 0.26 on PAP in the current split studies. The average difference in the current study was higher (−0.18 vs. −0.12). However, our patients had more severe OSA (57.3 ± 34.7 vs. 33.0 ± 28.0 hr−1) and a higher ORPNREM in the diagnostic study (1.05 ± 0.32 vs. 0.69 ± 0.24) which likely explains the higher average change. Nonetheless, further studies are warranted to evaluate the relationship between ORP types and OSA severity to the long-term effects of CPAP on sleep structure.

It may also be argued that the findings of this study are of limited value because they are mainly relevant to severe and very severe OSA cases that would be treated anyway. However, although patients with AHI > 30 hr−1 would correctly be initiated on PAP, many of them fail to adhere to it. Thirty-six percent of patients with severe OSA (AHI 30–50) and 16% of patients with very severe OSA have ORP patterns other than the three responsive patterns (Table 2) and in most of these patients, sleep gets worse on PAP (Figure 2, A). In the future, if it is confirmed that patients with the six non-responsive types are not at risk of long-term complications if untreated with PAP, OSA therapy may then be not considered (or continued) in such patients.

Conclusions

The main conclusions are:

ORP architecture types can distinguish patients in whom OSA adversely affects sleep from those in whom it does not.

Sleep depth is minimally affected in patients with mild/moderate OSA except in one ORP type (type 1,3). Accordingly, in other ORP types, sleep symptoms at this degree of OSA severity are not likely due to OSA and these patients should be investigated for other causes of their symptoms.

ORP patterns are predictive of short-term PAP response.

Contributor Information

Magdy Younes, Sleep Disorders Center, Misericordia Health Center, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada; YRT Limited, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada.

Bethany Gerardy, YRT Limited, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada.

Eleni Giannouli, Sleep Disorders Center, Misericordia Health Center, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada.

Jill Raneri, Sleep Centre, Foothills Medical Centre, Department of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada.

Najib T Ayas, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

Robert Skomro, Division of Respirology, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Canada.

R John Kimoff, Respiratory Division, McGill University Health Centre, Respiratory Epidemiology Clinical Research Unit and Meakins-Christie Laboratories, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada.

Frederic Series, Unité de Recherche en Pneumologie, Centre de Recherche, Institut Universitaire de Cardiologie et de Pneumologie de Québec, Université Laval, Québec, QC, Canada.

Patrick J Hanly, Sleep Centre, Foothills Medical Centre, Department of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada; Department of Medicine, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada; Hotchkiss Brain Institute, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada.

Andrew Beaudin, Hotchkiss Brain Institute, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada; Department of Clinical Neurosciences, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada.

Funding

PH is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and has received income from Dream Sleep Respiratory Services, Powell Mansfield Inc, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Paladin Labs, and Eisai Ltd. RJK is funded by Canadian Institutes of Health Research, holds research operating funds from Signifier Medical and advisory board income from Bresotec Inc, Powell Mansfield Inc, and Eisai Ltd. AEB was supported by postdoctoral fellowships from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Canadian Alzheimer Association & Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging (CCNA), and Campus Alberta Neuroscience.

Disclosure Statement

Financial disclosures: M.Y. developed the ORP method described in this report. He has a patent on the ORP technology. The technology has been licensed to Cerebra Health in Winnipeg. He is a shareholder and receives royalties from Cerebra Health. Nonfinancial disclosures: Nothing to disclose.

Data Availability

Data used in this study are available to academic investigators upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Edinger JD, et al. Impact of daytime sleepiness and insomnia on simple and complex cognitive task performances. Sleep Med. 2021;87:46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2021.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Li J, et al. Excessive daytime sleepiness and cardiovascular mortality in US adults: a NHANES 2005-2008 follow-up study. Nat Sci Sleep. 2021;13:1049–1059. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S319675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhou J, et al. A review of neurocognitive function and obstructive sleep apnea with or without daytime sleepiness. Sleep Med. 2016;23:99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2016.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Merlino G, et al. Insomnia and daytime sleepiness predict 20-year mortality in older male adults: data from a population-based study. Sleep Med. 2020;73:202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Newman AB, et al. Daytime sleepiness predicts mortality and cardiovascular disease in older adults. The Cardiovascular Health Study Research Group. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(2):115–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03901.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Westwell A, et al. Sleepiness and safety at work among night shift NHS nurses. Occup Med. 2021;71(9):439–445. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqab137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Catarino R, et al. Sleepiness and sleep-disordered breathing in truck drivers: risk analysis of road accidents. Sleep Breath. 2014;18(1):59–68. doi: 10.1007/s11325-013-0848-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bioulac S, et al. Risk of motor vehicle accidents related to sleepiness at the wheel: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep. 2017;40(10). doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsx134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bertisch SM, et al. S. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration and risk of incident cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: Sleep Heart Health Study. Sleep. 2018;41(6). doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vgontzas AN, et al. Insomnia with short sleep duration and mortality: the Penn State cohort. Sleep. 2010;33(9):1159–1164. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.9.1159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vgontzas AN, et al. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration: the most biologically severe phenotype of the disorder. Sleep Med Rev. 2013;17(4):241–254. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2012.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bathgate CJ, et al. Objective but not subjective short sleep duration associated with increased risk for hypertension in individuals with insomnia. Sleep. 2016;39(5):1037–1045. doi: 10.5665/sleep.5748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fernandez-Mendoza J, et al. Objective short sleep duration increases the risk of all-cause mortality associated with possible vascular cognitive impairment. Sleep Health. 2020;6(1):71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2019.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Redline S, et al. The effects of age, sex, ethnicity, and sleep-disordered breathing on sleep architecture. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(4):406–418. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.4.406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Younes M, et al. Characteristics and reproducibility of novel sleep EEG biomarkers and their variation with sleep apnea and insomnia in a large community-based cohort. Sleep. 2021;44(10). doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsab145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Younes M, et al. Mechanism of excessive wake time when associated with obstructive sleep apnea or periodic limb movements. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020;16(3):389–399. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.8214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mazzotti DR, et al. Symptom subtypes of obstructive sleep apnea predict incidence of cardiovascular outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(4):493–506. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201808-1509oc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Seneviratne U, et al. Excessive daytime sleepiness in obstructive sleep apnea: prevalence, severity, and predictors. Sleep Med. 2004;5(4):339–343. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gottlieb DJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of obstructive sleep apnea: a review. JAMA. 2020;323(14):1389–1400. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sweetman A, et al. Co-Morbid Insomnia and Sleep Apnea (COMISA): prevalence, consequences, methodological considerations, and recent randomized controlled trials. Brain Sci. 2019;9(12):371. doi: 10.3390/brainsci9120371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stroe AF, et al. Comparative levels of excessive daytime sleepiness in common medical disorders. Sleep Med. 2010;11(9):890–896. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Budhiraja R, et al. Prevalence and polysomnographic correlates of insomnia comorbid with medical disorders. Sleep. 2011;34(7):859–867. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Younes M, et al. Odds ratio product of sleep EEG as a continuous measure of sleep state. Sleep. 2015;38(4):641–654. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Younes M, et al. Comparing two measures of sleep depth/intensity. Sleep. 2020;43(12). doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsaa127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Smith MG, et al. Traffic noise-induced changes in wake-propensity measured with the Odds-Ratio Product (ORP). Sci Total Environ. 2022;805:150191. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Younes M, et al. Sleep architecture based on sleep depth and propensity: patterns in different demographics and sleep disorders and association with health outcomes. Sleep. 2022;45(6):zsac059. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsac059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lechat B, et al. A novel EEG marker predicts perceived SLEEPINESS AND poor sleep quality. Sleep. 2022;45(5):zsac051. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsac051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Berry RB, et al.; for the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. Version 2.4. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Younes M, et al. Reliability of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine rules for assessing sleep depth in clinical practice. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(2):205–213. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Younes M. Role of respiratory control mechanisms in the pathogenesis of obstructive sleep disorders. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105(5):1389–405. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90408.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. White DP, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea. Compr Physiol. 2012;2(4):2541–2594. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c110064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Malhotra A, et al. Performance of an automated polysomnography scoring system versus computer-assisted manual scoring. Sleep. 2013;36(4):573–582. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ahmadi N, et al. Clinical diagnosis of sleep apnea based on single night of polysomnography vs. two nights of polysomnography. Sleep Breath. 2009;13(3):221–226. doi: 10.1007/s11325-008-0234-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bittencourt LR, et al. The variability of the apnoea-hypopnoea index. J Sleep Res. 2001;10(3):245–251. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2001.00255.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Penner CG, et al. The odds ratio product (an objective sleep depth measure): normal values, repeatability, and change with CPAP in patients with OSA. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019;15(8):1155–1163. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.7812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this study are available to academic investigators upon reasonable request.