Significance

This project highlights the utility of collaborative research networks to gain collective insights for pandemic influenza decision-making through the comparison and ensembling of diverse models. While this project started in 2019, prior to the emergence of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, lessons learned from the pandemic underscore the need to build out systems for comparing, aggregating, and interpreting simulations from multiple infectious disease mathematical models during respiratory virus pandemics.

Keywords: Influenza, modelling, pandemics, infectious disease, epidemiology

Abstract

When an influenza pandemic emerges, temporary school closures and antiviral treatment may slow virus spread, reduce the overall disease burden, and provide time for vaccine development, distribution, and administration while keeping a larger portion of the general population infection free. The impact of such measures will depend on the transmissibility and severity of the virus and the timing and extent of their implementation. To provide robust assessments of layered pandemic intervention strategies, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) funded a network of academic groups to build a framework for the development and comparison of multiple pandemic influenza models. Research teams from Columbia University, Imperial College London/Princeton University, Northeastern University, the University of Texas at Austin/Yale University, and the University of Virginia independently modeled three prescribed sets of pandemic influenza scenarios developed collaboratively by the CDC and network members. Results provided by the groups were aggregated into a mean-based ensemble. The ensemble and most component models agreed on the ranking of the most and least effective intervention strategies by impact but not on the magnitude of those impacts. In the scenarios evaluated, vaccination alone, due to the time needed for development, approval, and deployment, would not be expected to substantially reduce the numbers of illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths that would occur. Only strategies that included early implementation of school closure were found to substantially mitigate early spread and allow time for vaccines to be developed and administered, especially under a highly transmissible pandemic scenario.

Viral respiratory pandemics can cause large numbers of serious illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths, especially in groups at increased risk for severe outcomes (e.g., older adults, very young children, pregnant women, and those with certain chronic medical conditions). When a pandemic emerges, however, there will likely be a lag in the availability of vaccines to curb these health outcomes. Therefore, much of the early pandemic response will require other measures to slow transmission of the virus or treat illness until a vaccine becomes available. The implementation of prevaccination mitigation measures (including those described in ref. 1 such as temporarily exercising remote learning options in schools, cancellation of mass gatherings, and widespread use of therapeutics) may temporarily slow the spread or reduce the impact of a pandemic virus in the community, allowing time for a vaccine to be developed, distributed, and administered. As seen during the COVID-19 pandemic, public health authorities will need to decide on an appropriate set of prevaccination mitigation measures, including how and when to implement those that are disruptive to society (1). For example, a machine learning study found that NPIs (nonpharmaceutical intervention) are most effective for controlling influenza pandemics when coupled with other interventions (2), and systematic reviews of NPIs found that timing of school closure and reopening around other interventions (e.g., vaccination campaigns) is an important mitigation strategy considering the adverse social costs (1, 3).

The 2009 H1N1 and COVID-19 pandemics have emphasized the utility of and need for mathematical models to help inform these decisions and estimate the potential effects of pandemic mitigation measures (4, 5). While several models have sought retrospectively to estimate the effects of physical or in-person school closures, therapeutics, and vaccination during seasonal influenza epidemics and the 1918, 1957, 1968, and 2009 influenza pandemics (6–10), few examples exist that leverage multiple models together to help policymakers make informed decisions during the early phase of an emerging pandemic. Examples include previous work to estimate the effect of NPIs on an emerging influenza pandemic and (11) recent work to analyze multiple COVID-19 mathematical models to inform different NPI and vaccination policies in the United States (2, 3, 12–14). One influenza modeling study found that NPIs and the timing of school closures are crucial for reducing disease burden and mitigating transmission, particularly when population-level vaccine coverage is low (11).

To enhance the utility of multiple models to estimate the impact of mitigation measures on an emerging pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) funded a network of academic groups to build a framework for pandemic influenza model development and comparison. This network, which consisted of groups from Northeastern University, Columbia University, the University of Texas at Austin/Yale University, Imperial College London/Princeton University, and the University of Virginia, quantified the impact of vaccines, antivirals, and school closures on illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths during three influenza pandemic scenarios developed collaboratively by the CDC and participating teams. One scenario was based on data from the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, while the other two were hypothetical and explored different assumptions about preexisting immunity in the population or the levels of disease transmissibility and clinical severity. This study describes the results from the network.

Materials and Methods

Models.

Six distinct models were included as part of this network from the five academic groups. Most groups primarily utilized compartmental models. Detailed information on the structure, calibration, and parameterization of each of the models can be found in SI Appendix, Appendices 1 and 2. Briefly, Columbia University implemented 2 models: 1) a state-level age-stratified metapopulation model (COL) and 2) a national-level age-stratified Susceptible-Infected-Recovered-Susceptible (SIRS)/SIR-Vaccinated-Susceptible model (SIRVS) (COL2). The University of Texas at Austin and Yale University together developed an age-stratified Susceptible-Exposed-Infected-Recovered (SEIR) model of 217 US metro areas representative of one-third of the US population (UTA). The University of Virginia implemented an age-stratified county-level metapopulation SEIR model in the United States, informed by individual-level synthetic contact networks for parameterizing the impact of interventions such as school closures (UVA). Northeastern University developed a global age-stratified metapopulation model (NEU). Last, Imperial College London and Princeton University together implemented an age-stratified, national-level SIR compartmental model (IMP).

Scenarios and Interventions.

To understand the implications of varying disease transmissibility and severity, we developed 3 influenza pandemic scenarios. The first scenario (“2009-like”) was based on published surveillance, serological, and epidemiological data from the fall wave of the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic with a simulation start date of July 1, 2009 (SI Appendix, Appendix 2, 2009 Parameter Table), although groups were free to use data from the spring wave to calibrate their models to account for immunity prior to the fall wave (15). The 2009 scenario served as a starting point for model calibration to help ground the hypothetical pandemic scenarios in empirical data. The second scenario (PAN1) had identical disease transmission and severity parameters to those used for the 2009 pandemic scenario; however, we assumed no prior immunity in the population (SI Appendix, Appendix 2, PAN1 and PAN2 Parameter Table). Illness in the third scenario (PAN2) was both more transmissible and clinically severe than the 2009 pandemic with no prior immunity assumed in the population (SI Appendix, Appendix 2, PAN1 and PAN2 Parameter Table). PAN1 and PAN2 simulation start dates were September 1st. For all scenarios, end dates were 1 y after the start dates. The CDC provided groups with data and assumptions for selected model parameters for the scenarios (SI Appendix, Appendix 2, PAN1 and PAN2 Parameter Table).

We considered pandemic vaccines; influenza antiviral treatment for infected, symptomatic individuals; and physical kindergarten through 12 school closure interventions, simulated both individually and in combination (see Table 1 and SI Appendix, Appendix for Specific Parameters). School closures were chosen because they were a key early social distancing intervention recommended during influenza pandemics (1), and calculations for incidence triggers were based on the model’s geographic granularity. School reopening on December 2nd was dependent on when 125 million individuals (about 40% of the US population) were vaccinated in 2009 according to CDC’s FluVaxView. Vaccination rates varied across age groups (SI Appendix, Appendix 2 2009 Parameter Table). Overall, we considered 8 intervention combinations for the “2009-like” pandemic and 12 intervention combinations for each of the two hypothetical scenarios PAN1 and PAN2 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Table of pandemic scenarios and intervention names and descriptions

| Scenario | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 2009 H1N1 pandemic | |

| 2009-1 | No interventions | |

| 2009-2 | Vaccine (effectiveness, timing, and administration data from the 2009 pandemic) (16, 17) | |

| 2009-3 | Antivirals (treatment of infected, symptomatic individuals only; assumed supply would meet demand) | |

| 2009-4 | Vaccine and antivirals | |

| 2009-5 | School closure when illness incidence at model’s geographic resolution> 1%, reopen December 2 | |

| 2009-6 | Schools remain physically closed after summer break and do not reopen until December 2 | |

| 2009-7 | Vaccine, antivirals, and school closure when illness incidence >1% and reopen December 2 | |

| 2009-8 | Vaccine, antivirals, and schools do not reopen until December 2 | |

| PAN1 | R0 = 1.4, no prior immunity, and “2009-like” hospitalization and death rate | |

| HP01 | No interventions | |

| HP02 | “Earlier” vaccine availability: administration begins 100 d after September 1, 25 million per week | |

| HP03 | “Later” vaccine availability: administration begins 150 d after September 1, 25 million per week | |

| HP04 | School closure when illness incidence >1%, reopening occurs on the “earlier” vaccine availability timeline | |

| HP05 | School closure on October 28, reopening occurs on the “earlier” vaccine availability timeline | |

| HP06 | School closure when illness incidence >1%, reopening occurs on the “later” vaccine availability timeline | |

| HP07 | School closure on October 28, reopening occurs on the “later” vaccine availability timeline | |

| HP08 | Antivirals (treatment of infected, symptomatic individuals only; supply would meet demand) | |

| HP09 | “Earlier” vaccine availability, school closure when illness incidence >1%, and antivirals | |

| HP10 | “Earlier” vaccine availability, school closure on October 28, and antivirals | |

| HP11 | “Later” vaccine availability, school closure when illness incidence >1%, and antivirals | |

| HP12 | “Later” vaccine availability, school closure on October 28, and antivirals | |

| PAN2 | R0 = 1.7, no prior immunity, and 2× “2009-like” hospitalization and death rate for <65 age groups | |

| HP13 | No interventions | |

| HP14 | “Earlier” vaccine availability: administration begins 100 d after September 1, 25 million per week | |

| HP15 | “Later” vaccine availability: administration begins 150 d after September 1, 25 million per week | |

| HP16 | School closure when illness incidence >1%, reopening occurs on the “earlier” vaccine availability timeline | |

| HP17 | School closure on October 28, reopening occurs on the “earlier” vaccine availability timeline | |

| HP18 | School closure when illness incidence >1%, reopening occurs on the “later” vaccine availability timeline | |

| HP19 | School closure on October 28, reopening occurs on the “later” vaccine availability timeline | |

| HP20 | Antivirals (supply would meet demand) | |

| HP21 | “Earlier” vaccine availability, school closure when illness incidence >1%, and antivirals | |

| HP22 | “Earlier” vaccine availability, school closure on October 28, and antivirals | |

| HP23 | “Later” vaccine availability, school closure when illness incidence >1%, and antivirals | |

| HP24 | “Later” vaccine availability, school closure on October 28, and antivirals |

Results Submission.

Modeling groups provided 1) probability distributions based on predetermined bins of values for symptomatic illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths, 2) point estimates of the mean, median, 2.5th, 5th, 25th, 75th, 95th, and 97.5th percentile metrics for the cumulative numbers of symptomatic illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths, and 3) the mean, 2.5th, and 97.5th percentile metrics for the weekly peak numbers of symptomatic illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths. Here, “symptomatic illness” is defined as all those with symptomatic infection of pandemic influenza, including both individuals picked up as cases by surveillance systems and those who were not. After a review of the initial results, groups identified different interpretations of some prescribed scenario assumptions and parametrizations. Each group then refined their models to reconcile these differences.

Ensemble and Averted Burden Calculations.

We calculated ensemble estimates by taking the mean across all model output means and 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles to represent the ensemble 95% uncertainty interval (UI). We defined burden as the total symptomatic illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths. Averted burden was estimated by calculating the difference in the cumulative burden between the intervention and the no-intervention case. The percent change in cumulative and the week of peak burden were calculated by subtracting the burden under the given intervention scenario from the burden under the no-intervention scenario and dividing by the burden under the no-intervention scenario. We calculated delay in peak as the difference between the no-intervention and intervention peak week, with negative numbers indicating that the peak was projected to occur earlier in the intervention model. For each burden metric (averted burden, percent change in cumulative burden, percent change in peak burden, and delay in peak), we ranked the intervention combinations from the most effective (rank of 1) to least (rank of 7 for 2009-like; 11 for PAN1 and PAN2).

Results

“2009-Like” Scenario.

No intervention.

The overall projected epidemic trajectory was consistent between models in the no-intervention scenario (SI Appendix, Fig. S1), with the mean final percent of the population with symptomatic illness estimated to be 17% in the ensemble. Component model means ranged between 14% and 22% (SI Appendix, Table S1). This is comparable to the estimated overall clinical attack rate of 20.0% (range 14.2 to 29.4%) during the 2009 influenza pandemic (16). The projected cumulative hospitalization and mortality rates varied widely across models. The ensemble mean cumulative hospitalization rate was estimated to be 164 per 100,000, while component model means ranged between 96 and 283 per 100,000. The ensemble mean cumulative mortality rate was estimated to be 16 per 100,000, while component model means ranged from 7 to 27 per 100,000 (SI Appendix, Table S1).

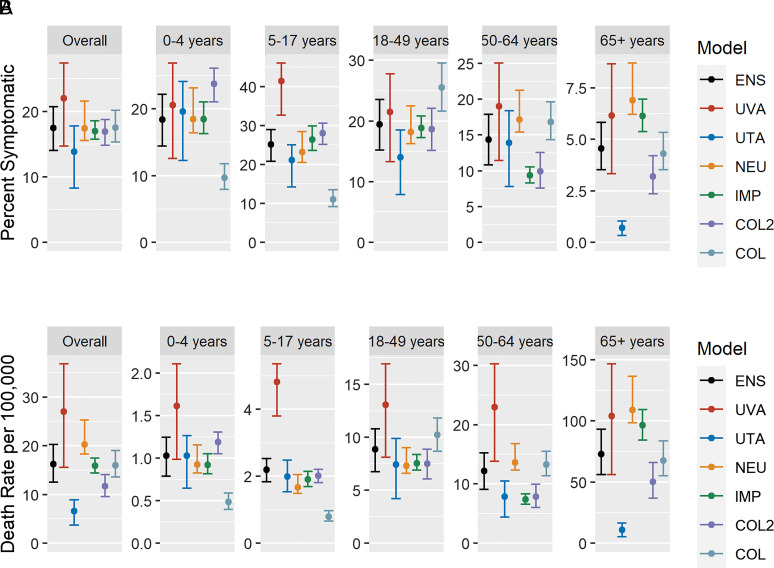

Overall, most symptomatic illnesses were seen in age groups younger than 65 y, with the distribution of cases in younger age groups varying across models (Fig. 1A). However, projected mortality rates were highest in the oldest age groups (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

(A) Age-specific final mean (95% UI) percent of the population with symptomatic illness for the “2009-like” no-intervention scenario. (B) Age-specific mean (95% UI) death rates per 100,000 population for the “2009-like” no-intervention scenario. (Note: y axes are varied between subplots.)

Impact of single interventions.

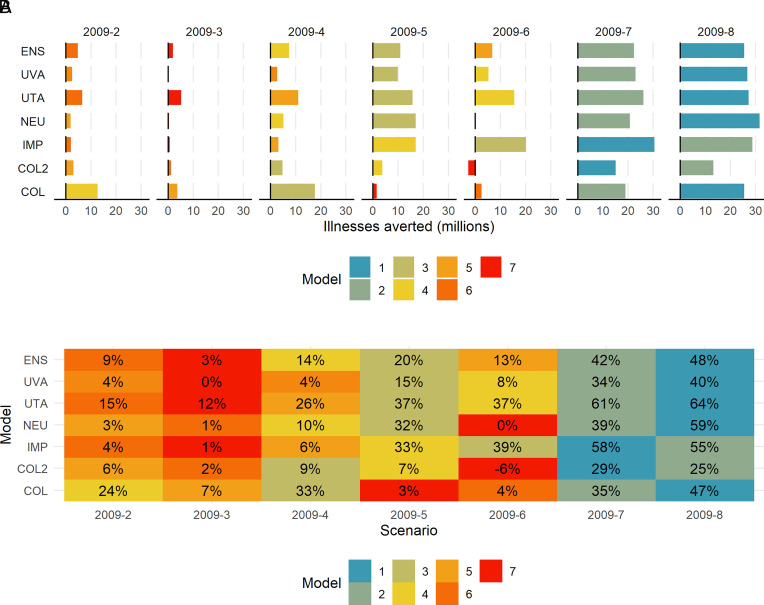

Single pharmaceutical interventions (e.g., vaccine or antivirals only) were ranked the least effective by both the ensemble and component models across burden metrics. Among most models, vaccination alone (2009-2), with the campaign starting in early-to-mid October, did not substantially reduce the overall burden, with only an ensemble mean estimated 9% decrease the final percent of the population with symptomatic illness (component model mean range: 4 to 24%) (Fig. 2B). Similarly, limited reductions in the percent of hospitalizations and deaths were estimated by the ensemble and component models (SI Appendix, Figs. S2B and S3B). Antivirals alone (2009-3) had a negligible impact on symptomatic illnesses; however, antivirals were estimated by the ensemble to avert on average 8% (range in component model means: 2 to 39%) of hospitalizations and 6% (range in component model means: 2 to 28%) of deaths (SI Appendix, Figs. S2B and S3B).

Fig. 2.

“2009-like” scenario (A) Total averted symptomatic illnesses in interventions compared to the no-intervention scenario. (B) Percent averted total symptomatic illnesses in interventions compared to the no-intervention scenario. (Note: see Table 1 for intervention abbreviation descriptions.)

As a single intervention, school closures were estimated by the ensemble to avert more symptomatic illnesses than vaccination alone or antivirals alone. Physical school closures triggered by an illness incidence of 1% or greater (2009-5) reduced the final percent of the population with symptomatic illness by an estimated 20%; however, there was a wide range in component model means (3 to 37%) (Fig. 2B). The estimated impact of keeping schools closed after summer (2009-6) showed similar trends but with lower reductions than closures based on the illness trigger. In addition to averting overall illnesses, the ensemble estimated that school closures would reduce the number of illnesses occurring during the peak week by 47% if schools were closed when illness incidence reaches 1% and by 36% when schools do not reopen after the summer. (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A).

Impact of multiple layered interventions.

The intervention ranked as the most effective in reducing the final percent of the population with symptomatic illness was a combination of vaccination, antivirals, and schools remaining closed through December 2nd (2009-8). This combination, which ranked first in the ensemble and in 4 out of 6 component models, was estimated to reduce the final percent symptomatically ill by a mean of 48% (range in component model means: 25 to 64%) and the peak magnitude by 61% (range in component model means: 31 to 72%) (Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, Figs. S4 and S5). Additionally, we found that layered interventions provided synergistic benefits where the estimated impact of layered interventions was greater than the summed impact of the individual interventions. For example, vaccines alone (2009-2) averted 9%, antivirals alone (2009-3) averted 3%, and keeping schools closed after summer alone (2009-6) averted 13% of illnesses (summing to 25% averted), but layering all 3 (2009-8) was estimated to avert almost double that value (48% of illnesses). This impact was robust across component models, with 5 out of 6 models estimating that this combination would avert the final percent symptomatically ill by 40% or more (Fig. 2). While as a single intervention closing schools on a 1% illness incidence trigger was more effective than keeping them closed after summer, when combined with vaccines and antivirals (2009-7), it was slightly less effective than the latter (2009-8) (Fig. 2).

PAN1 and PAN2 Scenarios.

No intervention.

The timing of the overall projected epidemic trajectory for PAN1 was consistent among models in the no-intervention scenario, with the peak week projected to occur mid-December to mid-January in all models (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A). The mean final percent of the population with symptomatic illness was estimated to be 27% in the ensemble. Component model means ranged between 22% and 36% (SI Appendix, Table S2). The mean cumulative hospitalization rate was estimated to be 295 per 100,000 in the ensemble (range in component model means: 136 to 463 per 100,000), while the mean cumulative mortality rate was estimated to be 32 per 100,000 in the ensemble (range in component model means: 20 to 44 per 100,000) (SI Appendix, Table S2).

The timing of the peak of PAN2 was earlier than PAN1, with the peak projected to occur in early November to mid-December (SI Appendix, Fig. S6B). The mean final percent of the population with symptomatic illness was higher in PAN2 and was estimated to be 34% in the ensemble and between 30% and 45% among the component models (SI Appendix, Table S3). The mean cumulative hospitalization rate was estimated to be 502 per 100,000 in the ensemble and 188 to 834 per 100,000 in the component models, while the mean cumulative mortality rate was estimated to be 55 per 100,000 in the ensemble and between 39 and 79 per 100,000 people in the component models (SI Appendix, Table S3).

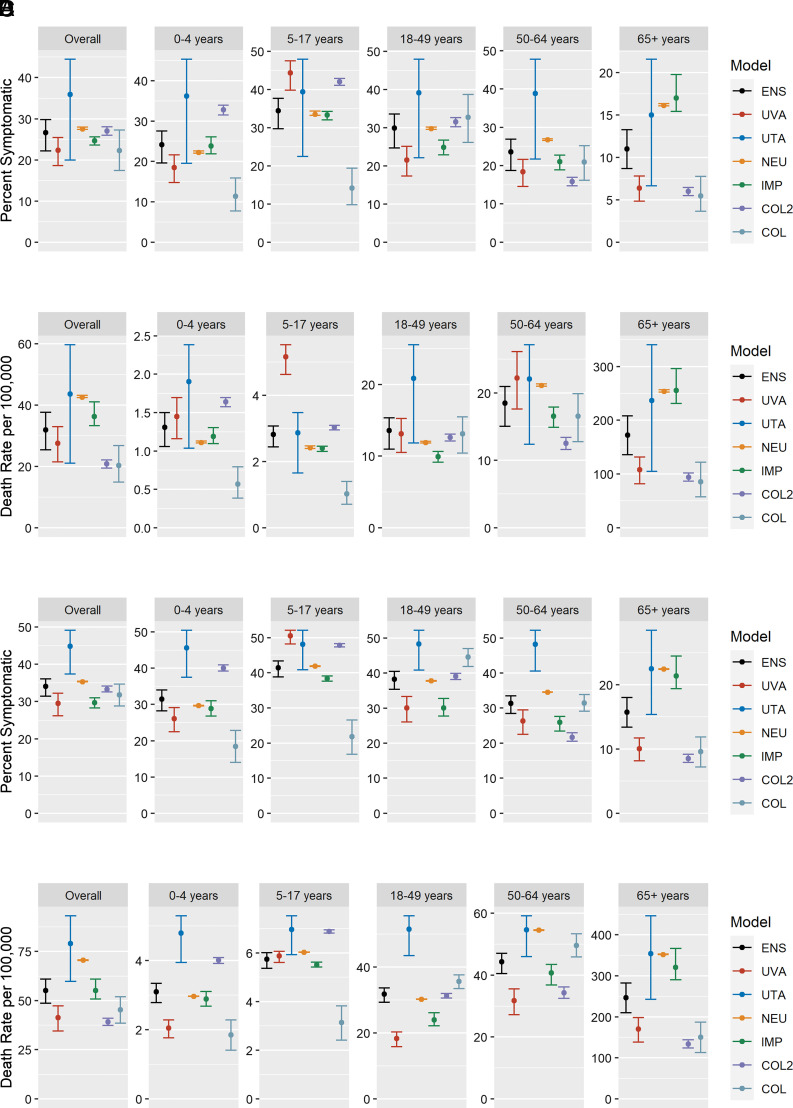

In both PAN1 and PAN2 scenarios, a majority of symptomatic illnesses were seen in age groups below 65, with distribution of cases in younger age groups varying between models (Fig. 3). However, projected mortality rates were highest in the oldest age group (Fig. 3). Between 70% and 90% of deaths occur in the oldest age group in the PAN1 scenario, while between 63% and 90% of deaths occur in that age group in the PAN2 (more severe) scenario (SI Appendix, Figs. S7 and S8).

Fig. 3.

(A) Age-specific final mean (95% UI) percent of the population with symptomatic illness for PAN1 no intervention. (B) Age-specific mean (95% UI) death rates per 100,000 population for PAN1 no intervention. (C) Age-specific final mean (95% UI) percent of the population with symptomatic illness for the PAN2 no-intervention scenario. (D) Age-specific mean (95% UI) death rates per 100,000 population for the PAN2 no-intervention scenario. (Note: y axes are varied between subplots.)

Impact of individual interventions.

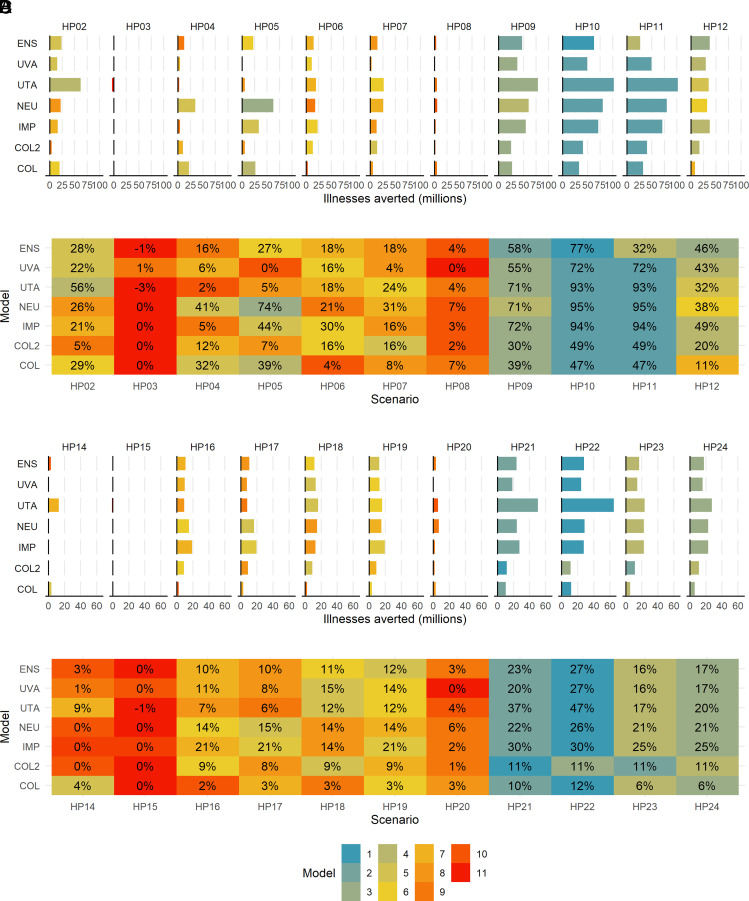

Vaccination, with earlier availability in the PAN1 scenario (HP02) was estimated by the ensemble to reduce the number of mean cumulative symptomatic illnesses by 28%, although the effect ranged between 5% and 56% averted in the component models (Fig. 4). However, this was only 3% (range in component models: 0 to 9%) when the virus is more transmissible and spreads quickly in PAN2 (HP14).

Fig. 4.

(A) PAN1 total averted symptomatic illnesses in interventions compared to no intervention. (B) PAN1 percent averted total symptomatic illnesses in interventions compared to no intervention. (C) PAN2 total averted symptomatic illnesses in interventions compared to no intervention. (D) PAN2 percent averted total symptomatic illnesses in interventions compared to no intervention. (Note: see Table 1 for intervention abbreviation descriptions.)

Antivirals alone (HP08 and HP20 in PAN1 and PAN2, respectively) reduced overall illnesses by 4% (range in component models: 0 to 7%) in PAN1 and by 3% (range in component models: 0 to 6%) in PAN2 (Fig. 4). However, antivirals reduced hospitalizations by 13% (range in component models: 3 to 35%) in PAN1 and by 13% (range in component models: 2 to 34%) in PAN2 and deaths by 11% (range in component models: 3 to 23%) in PAN1 and by 10% (range in component models: 2 to 23%) in the more severe PAN2 (SI Appendix, Figs. S9–S12).

The models varied widely in their estimate of the effect of school closure on October 28 vs. school closure when symptomatic illnesses reach 1% in the PAN1 scenario, regardless of when schools reopened (January vs. March reopening when 125 million doses were distributed in the earlier vs. later vaccination timelines). When schools reopened in January, the ensemble indicated that closing schools on October 28 (HP05) resulted in a 27% (range in component model means: 0 to 74%) reduction in final symptomatic illnesses, whereas the illnesses >1% trigger (HP04) resulted in a 16% (range in component model means: 2 to 41%) reduction (Fig. 4B).

The models were more in agreement regarding school closure and reopening timing for the PAN2 scenario, but the benefit of school closures was smaller in the event of a more transmissible pandemic (Fig. 4D).

Impact of layered interventions.

In the PAN1 scenario, early vaccine availability paired with school closures with a 1% illness trigger and antivirals were estimated by the ensemble to avert 58% (range in component model means: 30 to 72%) of the mean total symptomatic illnesses (HP09) (Fig. 4B). Under the same vaccine availability assumption but closing schools on October 28 (HP10) increased this value to 77% (range in component model means: 47 to 95%). These two strategies but with later vaccine availability were estimated by the ensemble to reduce total symptomatic illnesses by 32% and 46%, respectively (HP11 and HP12). The peak of symptomatic illnesses was reduced by 50 to 76% in the ensemble across the layered interventions (SI Appendix, Fig. S13A).

In the PAN2 scenario, the impact of layered interventions was reduced, as was the difference between the school closure strategies based on the 1% illness trigger vs. the closing on a set date (SI Appendix, Fig. S15). Even with earlier vaccine availability, the ensemble estimated that only around 23 to 27% (HP21 and HP22) of total symptomatic illnesses would be averted in either school closure strategy (Fig. 4D). This value dropped to 16 to 17% in interventions with later vaccine availability (HP23 and HP24). The peak was reduced by 38 to 41% in the ensemble across the layered interventions (SI Appendix, Fig. S15A).

The intervention ranked as most effective in reducing the final percent of the population with symptomatic illness was the same combination in both PAN1 and PAN2: earlier vaccination, school closure on October 28, and antivirals; this was ranked first in the ensemble and in five out of six models for PAN2 (Fig. 4). The next most effective intervention was early vaccination, school closure with the illness prevalence trigger of 1%, and antivirals.

Discussion

In this study, we describe efforts to evaluate the impact of pandemic influenza vaccinations, influenza antiviral treatment for symptomatic individuals, and school closures in multiple pandemic influenza scenarios. This study provided estimates from multiple models for the potential impacts of these interventions, both when used alone and in combination, allowing for assessment of the potential health benefits of the interventions. In addition, this study provides a framework to help compare and combine the results of multiple models into ensembles for policy development. As demonstrated during the current COVID-19 pandemic, this multimodel process, while challenging to accomplish in real time, can be particularly useful for helping inform decisions about larger-scale intervention strategies, including community reopening policies, the tradeoffs between increasing vaccination coverage and decreasing adherence of NPIs, and an assessment of the impact of expanding SARS-CoV-2 vaccination of children ages 5 to 11 (12–14, 17). This approach offers the ability to compare estimates from multiple models, allowing for the critical scientific assessment of how similar or dissimilar the individual modeling results are, while enabling the ability to generate ensembles (when appropriate) to summarize overall findings. In addition to informing and aiding decisions related to pandemic intervention policies, insights from this multimodel approach provide a way to understand the robustness of model findings across different modeling techniques and a way to better understand when, how, and why modeling results vary. These efforts can help improve the ability of models to inform future public action.

One major area of agreement between models was the rank order of the sets of interventions that would be the least and most effective at preventing cases, hospitalizations, and deaths in each of the pandemic scenarios. In all pandemic scenarios evaluated, closing schools on a predetermined date (or keeping them closed through summer and fall in the “2009-like” scenario) instead of closing schools when illness prevalence exceeded 1%, paired with vaccination and antiviral use, produced the greatest reductions of symptomatic illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths. In addition, this study highlighted that irrespective of its availability 100 or 150 d after identification of the virus, vaccination was likely to be of limited benefit when used alone because the novel virus spreads quickly in the population before vaccines are available. Instead, our findings suggested that vaccination should be paired with school closures and antiviral treatment to ensure more effective mitigation of transmission and disease burden. While this finding was robust across ensemble and component models, the estimated reductions in influenza outcomes may be an overestimate of the impact of vaccinations as the coverage and timeline evaluated here (ability to vaccinate 25 million people per week starting from either 100 d or 150 d after identification of the pandemic virus) could be optimistic given current influenza vaccine production timelines. For example, the first doses of vaccine for 2009 H1N1 were available approximately 180 d after virus detection (18), and vaccine administration rates never exceeded 18 million per week for the COVID-19 pandemic (9, 19). These findings underscore the continued need to invest in vaccine production technologies that can increase the speed with which influenza vaccines can be produced and for communities to plan for the use of NPIs like school closure, depending on the severity of the pandemic, to help slow the spread of pandemic influenza before a matched vaccine becomes widely available (1).

While models tended to agree on the overall interventions that would result in the greatest and least reductions in the number of cases, hospitalizations, and deaths averted, the estimated impact of the component models varied widely in certain scenarios and/or intervention combinations. For example, in the hypothetical PAN1 scenario, school closure on October 28 and reopening schools on the early vaccine timeline (HP05) were estimated to be the 3rd most effective intervention for reducing illnesses in the Northeastern University model with a 74% reduction but the 10th most effective in University of Virginia’s model with a 0% reduction in overall illnesses. Additionally, the University of Virginia’s model had the highest peak and higher attack rate and death rates for the 2009 H1N1 no-intervention scenario, while Columbia University model 2 had the highest peak and the University of Texas at Austin’s model had higher attack rates for the baseline PAN1 and PAN2 scenarios. Furthermore, the uncertainty bounds provided by individual models often did not overlap in many scenario/intervention combinations, emphasizing the variability in the models’ estimated impact of the interventions.

The variability described above can be driven by at least three sources: the differences in the initialization of the models, the differences in the interpretation or implementation of the parameters provided, and the differences in the model structures chosen. Like the Vaccine Impact Modeling Consortium, we provided documented assumptions and calibration data (SI Appendix) and defined the parameters and then worked with the groups to refine and iterate their results based on comparisons of results between the groups and the resulting discussion (20). As one such example, we identified that the interpretation and implementation of the basic reproduction number (R0) for the 2009 pandemic varied across the groups because the documented values included prior immunity in older age groups and could be impacted by the inclusion of seasonal variation or humidity forcing in the models, which we clarified for future submissions. Because of these systematic efforts, remaining differences among model results are more likely due to different choices for the initial conditions and model structures, including the presence of geographic heterogeneity in the model structure (SI Appendix, Appendix 2, 2009 Parameter Table). Component models that had geographical granularity at the state or county level (COL, UTA, UVA, and NEU) often provided results that were more consistent with each other. Further efforts to identify the drivers of the differences in model results are warranted to better understand, verify, and explain their source, which will continue to enhance the utility of multimodel networks to aid public health decision-making.

This study is subject to certain limitations. We had to strike a balance between the number of scenarios that were feasible for groups to run while also capturing a range of plausible interventions that might be considered during an emerging influenza pandemic. Therefore, we did not implement all possible combinations of single interventions (e.g., school closure and antivirals), nor did we consider the full suite of NPIs, such as widespread societal closures, as these had not previously been part of the recommended NPIs for pandemic influenza (1). Future work will need to consider the NPIs that have been utilized widely during the COVID-19 pandemic to better understand how these measures might mitigate the impact of future influenza pandemics and reduce the need for potentially more disruptive measures, like physical school closures. In addition, we did not include an analysis of the anticipated costs and societal disruptions of the interventions considered. Socioeconomic impact analyses incorporating pharmaceutical costs, number of school days lost, etc., will help ascertain the true impact of such interventions. Finally, the ensemble estimates generated in this analysis can produce patterns not seen in component models if there is wide variation in results. For example, multiple peaks over time in disease burden can be seen in the ensemble of the PAN1 intervention models despite most component models only predicting single peaks in disease burden. Further work to generate ensembles using different approaches that may be more robust to these situations are in development.

Conclusions

Despite the variation in modeling approaches, it is notable that certain key findings emerged. Models generally agreed that physical school closures were fundamental to mitigating burden early in an influenza pandemic, especially for a virus that is highly transmissible and/or more likely to cause severe outcomes. While the timing of vaccine availability was found to be important, the use of vaccines alone did not avert a large fraction of illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths in many of the scenarios evaluated. Antivirals were found to avert a moderate percentage of deaths but would not avert a large majority. Developing a process to ensemble modeling results during a public health emergency is an important strategy to gain cohesive insight from multiple models and capture the appropriate level of uncertainty inherent in pandemic modeling.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

P.V.P., C.R., L.A.M., B.L., M.E.H., I.L., A.V., S.P., S.K., J.S., N.A., and M.B. designed research; L.A.M., Z.D., R.P., J.A.A.-M., B.L., S.V., J.S., J.C., M.O., M.L.W., S.E., L.W., M.C., A.P.y.P., J.T.D., M.E.H., A.V., S.P., M.G., S.K., J.S., D.J.H., and N.A. performed research; P.V.P., M.K.S., and M.B. analyzed data; and P.V.P. and M.B. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All analyses and visualizations were conducted in R version 3.6.3 (R Project for Statistical Computing). CSV data have been deposited in FluCode (https://github.com/cdcepi/FluCode) (21).

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Qualls N., et al. , Community mitigation guidelines to prevent pandemic influenza–United States, 2017. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 66, 1–34 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qiu Z., et al. , The effectiveness of governmental nonpharmaceutical interventions against COVID-19 at controlling seasonal influenza transmission: An ecological study. BMC Infect. Dis. 22, 331 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fong M. W., et al. , Nonpharmaceutical measures for pandemic influenza in nonhealthcare settings-social distancing measures. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 26, 976–984 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sypsa V., Hatzakis A., School closure is currently the main strategy to mitigate influenza A(H1N1)v: A modeling study. Euro. Surveill. 14, 19240 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bajardi P., et al. , Modeling vaccination campaigns and the Fall/Winter 2009 activity of the new A(H1N1) influenza in the Northern Hemisphere. Emerg. Health Threats J. 2, e11 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mills C. E., Robins J. M., Lipsitch M., Transmissibility of 1918 pandemic influenza. Nature 432, 904–906 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vynnycky E., Edmunds W. J., Analyses of the 1957 (Asian) influenza pandemic in the United Kingdom and the impact of school closures. Epidemiol. Infect. 136, 166–179 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larson R. C., Teytelman A., Modeling the effects of H1N1 influenza vaccine distribution in the United States. Value Health 15, 158–166 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borse R. H., et al. , Effects of vaccine program against pandemic influenza A(H1N1) virus, United States, 2009–2010. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 19, 439–448 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Germann T. C., et al. , Mitigation strategies for pandemic influenza in the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 5935–5940 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halloran M. E., et al. , Modeling targeted layered containment of an influenza pandemic in the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 4639–4644 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shea K., et al. , COVID-19 reopening strategies at the county level in the face of uncertainty: Multiple models for outbreak decision support. medRxiv [Preprint] (2020). 10.1101/2020.11.03.20225409 (Accessed 23 January 2022). [DOI]

- 13.Borchering R. K., et al. , Modeling of future COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths, by vaccination rates and nonpharmaceutical intervention scenarios–United States, April-September 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. 70, 719–724 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borchering R. K., et al. , Impact of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination of children ages 5-11 years on COVID-19 disease burden and resilience to new variants in the United States, November 2021-March 2022: A multi-model study. medRxiv [Preprint] (2022). 10.1101/2022.03.08.22271905 (Accessed 1 June 2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Jhung M. A., et al. , Epidemiology of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 52, S13–S26 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shrestha S. S., et al. , Estimating the burden of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) in the United States (April 2009–April 2010). Clin. Infect. Dis. 52, S75–S82 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reich N. G., et al. , Collaborative hubs: Making the most of predictive epidemic modeling. Am. J. Public Health 112, 839–842 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Final estimates for 2009–10 Seasonal Influenza and Influenza A (H1N1) 2009 Monovalent Vaccination Coverage – United States (August 2009 through May, 2010.). https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage_0910estimates.htm.

- 19.Diesel J., et al. , COVID-19 vaccination coverage among adults–United States, December 14, 2020-May 22, 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortality Wkly. Rep. 70, 922–927 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toor J., et al. , Lives saved with vaccination for 10 pathogens across 112 countries in a pre-COVID-19 world. eLife 10, e67635 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prasad P. V., et al. , Multi-modeling approach to evaluating efficacy of layering pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical interventions for influenza pandemics. GitHub. FluCode Repository. https://github.com/cdcepi/FluCode/. Deposited 7 July 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All analyses and visualizations were conducted in R version 3.6.3 (R Project for Statistical Computing). CSV data have been deposited in FluCode (https://github.com/cdcepi/FluCode) (21).