Abstract

Introduction

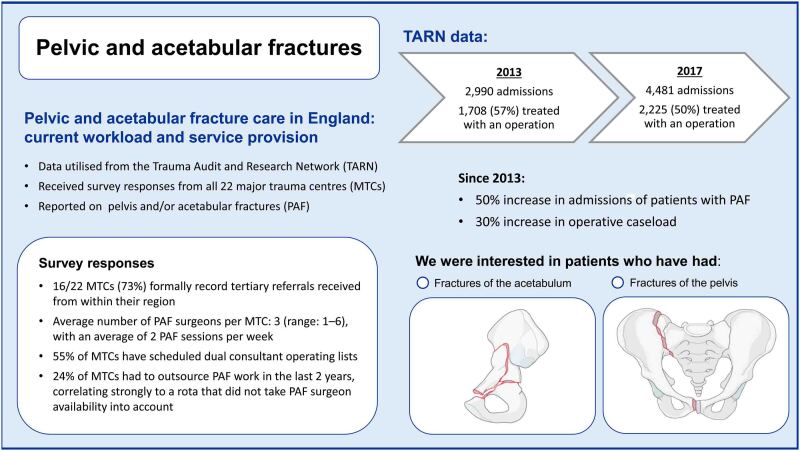

Fractures of the pelvis and acetabulum (PAFs) are challenging injuries, requiring specialist surgical input. Since implementation of the major trauma network in England in 2012, little has been published regarding the available services, workforce organisation and burden of PAF workload. The aim of this study was to assess the recent trends in volume of PAF workload, evaluate the provision of specialist care, and identify variation in available resources, staffing and training opportunity.

Methods

Data on PAF volume, operative caseload, route of admission and time to surgery were requested from the Trauma Audit and Research Network. In order to evaluate current workforce provision and services, an online survey was distributed to individuals known to provide PAF care at each of the 22 major trauma centres (MTCs).

Results

From 2013 to 2019, 23,823 patients with PAF were admitted to MTCs in England, of whom 12,480 (52%) underwent operative intervention. On average, there are 3,971 MTC PAF admissions and 2,080 operative fixations each year. There has been an increase in admissions and cases treated operatively since 2013. Three-quarters (78%) of patients present directly to the MTC while 22% are referred from regional trauma units. Annually, there are on average 37 operatively managed PAF injuries per million population. Notwithstanding regional differences in case volume, the average number of annual PAF operative cases per surgeon in England is 30. There is significant variation in frequency of surgeon availability. There is also variation in rota organisation regarding consistent specialist surgeon availability.

Conclusions

This article describes the provision of PAF services since the reorganisation of trauma services in England. Future service development should take into account the current distribution of activity, future trends for increased volume and casemix, and the need for a PAF registry.

Keywords: Pelvis, Acetabulum, Pelvic and acetabular fracture

Introduction

Fractures of the pelvis and acetabulum (PAFs) are challenging injuries to treat. They are often the result of high energy trauma and accompanied by multisystem injuries, although they are also increasingly seen following low energy trauma in the geriatric population with associated osteopenia.1 Where instability or displacement are present, these injuries require specialist surgical input and associated healthcare resources to ensure optimum outcome.2 Morbidity from these injuries can be profound and long term.3 Accordingly, well organised systems are needed to maximise prospects of recovery.

In England, the establishment of the major trauma network (MTN) in 2012 has led to improved outcomes and survival from major trauma.4 Since these systemic changes, little has been reported regarding current service provision, workload and organisation of the care for patients with PAF.

The MTN has allowed centralisation of care for patients with PAF to the regional major trauma centre (MTC) via a hub and spoke model. Differences may exist in each MTC in terms of service provision, organisation, training opportunity and available resources. The aims of this study were to: 1) assess current and recent trends in volume of patients presenting with PAF; 2) assess current and recent trends in workload regarding injury severity and the number of PAF cases requiring operative intervention; 3) evaluate the current provision of PAF specialist care across England; 4) identify differences in available resources, staffing levels, training opportunities and future organisational aspirations in these specialist centres.

Methods

This study used data from the Trauma Audit and Research Network (TARN). TARN was established over 25 years ago, acting as a trauma registry from which standards of care can be audited and research generated.5 All MTCs are required to submit data to TARN via a secure online data submission tool. A tiered best practice tariff financial incentive is available if certain criteria during the care of patients with traumatic injuries are achieved. A formal request for information was sent to TARN. Our request for information included:

-

•

number of PAF cases admitted to MTCs per year;

-

•

number of PAF cases admitted to MTCs that underwent operative treatment per year;

-

•

proportion of PAF cases received to MTCs directly versus via tertiary referral from regional trauma units;

-

•

time to surgery for those PAF cases treated operatively.

Second, a survey was generated, using an online platform.6 This was distributed to all 22 adult MTCs in England to investigate differences in staffing levels, specialist surgeon availability, training opportunity, expertise, volume of surgical assistance and workforce organisation. The survey was sent to one or more individuals at each MTC known to provide specialist PAF care or to a senior team member familiar with the local organisation. An accompanying personal email was also sent to request survey completion. Responses were collected over a five-month period from January to May 2019. Research and ethics committee approval was not required as assessed using the Health Research Authority online decision tool.7

Results

TARN data

We were provided with the combined number of PAF admitted to all MTCs per year since 2013 (the first full year of data following establishment of the MTN), the number of these treated surgically, the number of direct admissions versus transfer from regional trauma units and stratification of injury severity. The following findings were noted:

Workload: From January 2013 to January 2019, 23,823 patients with PAF were admitted to MTCs. Of these, 12,480 (52%) underwent surgical intervention. The mean annual number of admissions since 2013 was 3,971, of which on average 2,080 were treated operatively. Based on estimates of the current population in England (55,977,200),8 this translates to 71 PAF admissions and 37 operatively managed cases per million population per year. The number of admissions with PAF per year has grown steadily since 2013 with an increase in absolute numbers of patients treated operatively (Table 1). The proportion of PAF admissions undergoing operative treatment demonstrated a slight reduction each year.

Table 1 .

Number of pelvic and acetabular fractures admitted to all major trauma centres

| Year | All admissions | Treated operatively |

|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2,990 | 1,708 (57%) |

| 2014 | 3,476 | 1,884 (54%) |

| 2015 | 3,918 | 2,079 (53%) |

| 2016 | 4,276 | 2,238 (52%) |

| 2017 | 4,481 | 2,225 (50%) |

| 2018 | 4,682 | 2,346 (50%) |

Injury severity

The proportion of patients presenting with more severe injuries (as evidenced by an abbreviated injury scale [AIS] score of 4+) undergoing operative intervention has remained relatively constant since 2013 with the exception of a slight reduction in 2017 and 2018 (Table 2). On average, 42% of patients undergoing PAF fixation have AIS 4+ while 58% have AIS 1–3.

Table 2 .

Major trauma centre pelvic and acetabular fracture admissions and operations categorised by abbreviated injury scale (AIS) score

| Year | AIS 1–3 | AIS 4+ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All admissions | Treated operatively | All admissions | Treated operatively | |

| 2013 | 2,013 | 982 (49%) | 977 | 726 (74%) |

| 2014 | 2,385 | 1,090 (46%) | 1,091 | 794 (73%) |

| 2015 | 2,712 | 1,214 (45%) | 1,206 | 865 (72%) |

| 2016 | 3,044 | 1,307 (43%) | 1,232 | 931 (76%) |

| 2017 | 3,092 | 1,297 (42%) | 1,389 | 928 (67%) |

| 2018 | 2,966 | 1,313 (44%) | 1,716 | 1,033 (60%) |

| Total | 16,212 | 7,203 (44%) | 7,611 | 5,277 (69%) |

Time to surgery

Among those patients presenting with PAF requiring operative intervention, since 2013, the mean time to surgery from MTC admission has remained static. The mean time to surgery was 52 hours. The data provided did not allow determination of the range or the specific time to surgery from time of injury for those directly admitted to MTC compared with those transferred from a trauma unit.

Route of admission

Although the absolute volume of patients presenting to MTCs with PAF has increased since 2013, the proportions presenting to the MTC either directly or via tertiary referral from a trauma unit have remained static. The mean percentage of patients presenting directly to the MTC since 2013 was 78% whereas 22% of patients presented to the MTC through tertiary referral from a trauma unit. The mean annual proportion of patients with PAF and AIS 1–3 presenting directly to the MTC was 75% compared with 66% for patients with AIS 4+ (Table 3).

Table 3 .

Direct major trauma centre admissions versus trauma unit transfer for patients with pelvic and acetabular fractures

| Year | AIS 1–3 | AIS 4+ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct admissions | Transfer | Direct admissions | Transfer | |

| 2013 | 1,608 (75%) | 405 (25%) | 716 (63%) | 261 (36%) |

| 2014 | 1,867 (72%) | 518 (28%) | 802 (64%) | 289 (36%) |

| 2015 | 2,154 (74%) | 558 (26%) | 879 (63%) | 327 (37%) |

| 2016 | 2,478 (77%) | 566 (23%) | 892 (62%) | 340 (38%) |

| 2017 | 2,484 (76%) | 608 (24%) | 1,071 (70%) | 318 (30%) |

| 2018 | 2,348 (74%) | 618 (26%) | 1,321 (70%) | 395 (30%) |

| Total | 12,939 (75%) | 3,273 (25%) | 5,681 (66%) | 1,930 (34%) |

Survey responses

During the study period, responses were received from all of the 22 MTCs.

Tertiary referral records

Sixteen MTCs (73%) formally record tertiary referrals received from within their region, either for advice or transfer of care.

Staffing

There are currently 69 whole time equivalent consultant surgeons routinely performing PAF fixation in England. The mean number of whole time equivalent specialist surgeons per MTC is 3 (range: 1–6). Notwithstanding the inevitable regional variations in workload that exist, taking into account the average annual national operative caseload, this amounts to 30 operative cases per surgeon per year.

Fourteen MTCs (64%) have regular scheduled PAF operating lists with a mean frequency of 2 days (2 sessions) per week (range: 0.5–4 days). Of the hospitals without regular scheduled PAF operating lists, a specialist surgeon is available three days per week in three hospitals, two days per week in three hospitals, five days per week in one hospital and on an informal ad hoc basis in one hospital.

Ten MTCs (45%) currently do not have regular, scheduled dual consultant operating lists for complex cases although four of these have an aspiration to formalise a regular dual consultant PAF operating list. Regarding operative assistance for PAF fixation cases, the mean number of assistants per case was 1.7 (range: 1–3). One MTC utilises surgical care practitioners while the remainder have a combination of post-Certificate of Completion Training fellows, training registrars or basic grade doctors.

Workforce organisation

In ten hospitals (45%), the availability of a specialist PAF surgeon was not considered in rota planning. Nevertheless, in all but three of these hospitals, leave was coordinated informally among the PAF surgeons to ensure consistent availability. Four MTCs (24%) reported having had to outsource cases because of specialist surgeon availability in the last two years; all of these hospitals had a rota that does not take into account PAF surgeon availability.

The results of our analysis of the TARN data and our survey findings are summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1 .

Infographic summarising the study findings

Discussion

In the late 1990s and 2000s, several articles highlighted the difficulties in ensuring timely, coordinated and consistent care for patients with PAF in England.2,5,9–11 There was little continuity in PAF care nationwide and great variation in case volume at each centre that managed these complex injuries.12 These articles coincided with wider publications noting the deficiencies in the management of trauma patients across the UK. The National Audit Office report Major Trauma Care in England, published in 2010,13 served as the final impetus for an overhaul of the management of severe trauma in England.

Utilising data from TARN, this study has been able to shed light on the burden of patients presenting with PAF since implementation of the MTN in England. The number of PAF patients admitted to MTCs has shown a modest increase each year since 2013. However, the proportion of all admissions with PAF undergoing operative management has declined from 57% in 2013 to 50% in 2018.

A number of contributory factors for this apparent trend may exist. Increased awareness and use of whole body computed tomography in patients with low and moderate energy trauma is likely to identify a subset of undisplaced fractures (particularly in the geriatric population), which may have previously gone undiagnosed and do not require surgical intervention.14,15 Furthermore, with expanding subspecialist knowledge of PAF injury patterns and increased complexity of treatment options, as has been reported previously, the ability and confidence of a general orthopaedic group to guide management decisions may have declined, resulting in a lower threshold for referral and transfer.5 Finally, this apparent trend may be a result of improved reporting to TARN since its inception, especially as the injuries most likely to have been reported initially will have been those undergoing operative intervention.

Our data demonstrate a gradual increase in the number of PAF cases treated operatively each year since 2013. This trend is likely to continue. It is also noteworthy that several novel randomised controlled trials investigating surgical versus non-surgical management of a variety of PAF injury patterns are currently ongoing in the UK. L1FE is examining surgical versus non-surgical management of lateral compression type 1 (LC1) injuries in the elderly population.16 AceFIT is a trial with three treatment arms comparing non-surgical treatment, operative fixation and operative fixation plus acute arthroplasty for displaced acetabular fractures in patients aged >60 years.17 TULIP is a surgical versus non-surgical trial for patients aged >16 years with a LC1 pelvic ring fracture that includes a complete sacral fracture.18

In the event that these studies demonstrate superiority of surgery, an additional huge increase in surgical workload could be expected. This trend will require advanced planning regarding healthcare resource provision and workforce management. Furthermore, while these trials are ongoing, the transfer of patients from trauma units to MTCs is likely to increase to allow assessment of suitability for inclusion. For example, an inclusion criterion of the L1FE study is an elderly patient sustaining a LC1 injury who subsequently fails a trial of mobilisation.16 These patients, who previously may have remained at the trauma unit, are more likely to be transferred for their trial of mobilisation and subsequent consideration of inclusion in the study. These changes in patient flow within the MTN will require appropriate healthcare resource provision.

In addition, workforce planning should also remain cognisant of the shifting epidemiology of PAF. Our ageing population has heralded an increase in low energy fragility fractures. The number of low energy fragility PAF cases are forecast to further increase.19,20 These injuries represent a distinct entity, compared with high energy PAF, and may require a different skillset such as the ability to perform simultaneous acute fracture fixation and arthroplasty. This changing demographic should be considered when coordinating a PAF workforce, and planning training and fellowship experience.

Our results demonstrate that approximately a third of patients presenting with PAF can consistently be expected to have an AIS of four or higher. This supports diversion of healthcare resources to MTCs for care of these patients.

There has been an increase in the absolute number of admissions of patients with PAF in recent years and there is an anecdotal trend for increased trauma unit referrals for management decisions. Both place additional demand on a finite resource. Despite this, there are six MTCs (27%) that currently do not formally record the number and outcomes of tertiary referrals for either opinion or transfer of care. Formally recording and documenting the volume of tertiary referrals may help provide evidence for the requirement of timetabled, funded sessions to review these referrals and relay management decisions in a structured, timely fashion.

Dual consultant operating has gained recent interest.21 The senior authors at our institution have had a positive experience of this. This is supported by our findings that at present, half of MTCs have regular, planned double consultant PAF surgeon operating lists. The majority of the remaining MTCs have an aspiration to provide this service in future, serving as further useful information with regard to management and workforce planning. Moreover, notwithstanding the inevitable regional variations in case volume, the average annual operative caseload per surgeon of 32 is noteworthy. This highlights the relative infrequency of these complex injuries and adds to the argument for regular dual consultant operating in order to maximise experience.

In addition, our findings also lend support to the establishment of a national PAF registry. This would provide direct lines of communication to aid difficult management decisions, a resource from which workforce planning and training can be guided, and a platform for sharing of outcome data from which further collaborative clinical trials can be established. Recently, PAF specialist consultant surgeons in England have successfully utilised a channel of direct digital communication via a WhatsApp Messenger (WhatsApp, Mountain View, CA, US) forum. Using anonymised information and images, this has provided a platform for expeditious feedback regarding treatment decisions for difficult or complex cases, and helps to mitigate against the challenges posed by an infrequent, heterogeneous and complex group of injuries. While this has proved a particularly useful resource to engender collaborative thinking, a more formalised and robust means of communicating clinical details, clinical images and management decisions may be beneficial.

There is evidence demonstrating the benefits of prompt definitive management of this severely injured patient cohort.22,23 This is reflected in the British Orthopaedic Association Audit Standards for Trauma.24 Despite this, half of all MTCs do not take into account availability of a PAF specialist surgeon and in five MTCs (23%), there is no coordination of absence among PAF surgeons. As a result, four MTCs (18%) have had to outsource PAF patients to other specialist centres for lack of available surgeon in the previous two years. This finding should prompt appropriate organisation of resources to enable better consistency of service provision.

Significant strengths of this study are that it is the first representation of PAF service organisation since the formation of the MTN and the 100% survey completion rate. However, it also has a number of limitations. Our findings from the TARN data regarding trends in workload rely on the accuracy and completeness of the data submitted. The quality of data submission may be variable and our findings may therefore not be a true representation.

Furthermore, only MTC TARN data were included. Accordingly, any PAF cases admitted and treated at a trauma unit will not be represented. It is unlikely that acute, traumatic PAF cases are being managed surgically at a trauma unit. Nevertheless, there is clearly a burden of patients with these injuries who do not require surgical intervention and remain at the trauma unit without referral, and this patient group is therefore not represented in our data. Finally, while our survey has shed valuable light on the differences in service organisation and provision, there are limitations inherent in survey research that are noteworthy.25,26

Conclusions

This study has demonstrated the current distribution of PAF workload in England following the restructuring of trauma care in 2012 and highlights the likely future trend for increased volume. PAF surgery is a relatively small field involving complex and technically demanding patients. In order to best manage this population, appropriate planning and distribution of funding, services and activity will be required to ensure adequate experience and training opportunities. This patient group would also be well served through collaborative work locally with dual consultant operating, and nationally through a PAF registry and ongoing peer-to-peer discussion of complex cases.

References

- 1.Herath SC, Pott H, Rollman MFet al. Geriatric acetabular surgery: Letournel’s contraindications then and now – data from the German Pelvic Registry. J Orthop Trauma 2019; 33(Suppl 2): S8–S13. 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harvie P, Chesser TJ, Ward AJ. The Bristol regional pelvic and acetabular fracture service: workload implications of managing the polytraumatised patient. Injury 2008; 39: 839–843. 10.1016/j.injury.2008.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bott A, Odutola A, Halliday Ret al. Long-term patient-reported functional outcome of polytraumatized patients with operatively treated pelvic fractures. J Orthop Trauma 2019; 33: 64–70. 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moran CG, Lecky F, Bouamra Oet al. Changing the system – major trauma patients and their outcomes in the NHS (England) 2008–17. E Clinical Medicine 2018; 2–3: 13–21. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2018.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solan MC, Molloy S, Packham Iet al. Pelvic and acetabular fractures in the United Kingdom: a continued public health emergency. Injury 2004; 35: 16–22. 10.1016/S0020-1383(03)00264-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Surveymonkey. www.surveymonkey.com (cited February 2021).

- 7.Health Research Authority. www.hra-decisiontools.org.uk/research (cited February 2021).

- 8.Office for National Statistics. Population Estimates for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland: Mid-2018. Newport: ONS; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edwards A. Top 10 TARN research publications. Emerg Med J 2015; 32: 966–968. 10.1136/emermed-2015-205454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giannoudis PV, Pohlemann T, Bircher M. Pelvic and acetabular surgery within Europe: the need for co-ordination of treatment concepts. Injury 2007; 38: 410–415. 10.1016/j.injury.2007.01.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geoghegan JM, Longdon EJ, Hassan K, Calthorpe D. Acetabular fractures in the UK. What are the numbers? Injury 2007; 38: 329–333. 10.1016/j.injury.2006.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geoghegan JM, Longdon EJ, Hassan Ket al. Acetabular surgical units: a directory for the United Kingdom. Injury 2010; 41: 677–679. 10.1016/j.injury.2008.06.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Audit Office. Major Trauma Care in England. London: NAO; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chidambaram S, Goh EL, Khan MA. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of whole-body computed tomography imaging in the management of trauma and injury. Injury 2017; 48: 1784–1793 10.1016/j.injury.2017.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clement ND, Court-Brown CM. Elderly pelvic fractures: the incidence is increasing and patient demographics can be used to predict the outcome. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2014; 24: 1431–1437. 10.1007/s00590-014-1439-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Surgical vs conservative treatment of LC1 pelvic fractures in the elderly. https://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN16478561 (cited January 2021).

- 17.Romanik J. AceFIT – a study comparing three methods of treatment of acetabular fractures (a type of hip fracture) in older patients; surgical fixation versus surgical fixation and hip replacement versus non-surgical treatment. https://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN16739011 (cited January 2021).

- 18.Cook L. Surgical vs non-surgical treatment of LC1 pelvic injuries. https://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN10649958 (cited January 2021).

- 19.Sullivan MP, Baldwin KD, Donegan DJet al. Geriatric fractures about the hip: divergent patterns in the proximal femur, acetabulum, and pelvis. Orthopedics 2014; 37: 151–157. 10.3928/01477447-20140225-50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanakaris NK, Greven T, West RMet al. Implementation of a standardized protocol to manage elderly patients with low energy pelvic fractures: can service improvement be expected? Int Orthop 2017; 41: 1813–1824. 10.1007/s00264-017-3567-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sutton PA, Rooney PS.. Multi-consultant operating. Bull R Coll Surg Engl 2018; 100: 329–332. 10.1308/rcsbull.2018.329 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katsoulis E, Giannoudis PV. Impact of timing of pelvic fixation on functional outcome. Injury 2006; 37: 1133–1142. 10.1016/j.injury.2006.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vallier HA, Cureton BA, Ekstein Cet al. Early definitive stabilization of unstable pelvis and acetabulum fractures reduces morbidity. J Trauma 2010; 69: 677–684. 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181e50914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.British Orthopaedic Association. The Management of Patients with Pelvic Fractures. London: BOA; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones TL, Baxter MA, Khanduja V. A quick guide to survey research. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2013; 95: 5–7. 10.1308/003588413X13511609956372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alderman AK, Salem B. Survey research. Plast Reconstr Surg 2010; 126: 1381–1389. 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ea44f9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]