Abstract

Introduction

National selection for higher surgical training (ST3+) recruitment in the UK is competitive. The process must prioritise patient safety while being credible, impartial and fair. During the COVID-19 pandemic, all face-to-face interviews were cancelled. Selection was based on a controversial isolated self-assessment score with no evidence checking taking place. From 2021, selection will take place entirely online. Although this has cost and time advantages, new challenges emerge.

Methods

We review surgical selection as it transitions to an online format and suggest validated methods that could be adapted from High Reliability Organisations (HRO).

Findings

Virtual selection methods include video interviewing, online examinations and aptitude testing. These tools have been used in business for many years, but their predictive value in surgery is largely unknown. In healthcare, the established online Multi-Specialty Recruitment Assessment (MSRA) examines generic professional capabilities. Its scope, however, is too limited to be used in isolation. Candidates and interviewers alike may have concerns about the technical aspects of virtual recruitment. The significance of human factors must not be overlooked in the online environment. Surgery can learn from HROs, such as aviation. Pilot and air traffic control selection is integral to ensuring safety. These organisations have already established digital selection methods for psychological aptitude, professional capabilities and manual dexterity.

Conclusion

National selection for higher surgical training (ST3+) can learn from HROs, using validated methods to prioritise patient safety while being acceptable to candidates, trainers and health service recruiters.

Keywords: COVID-19, Training, Human factors, Selection, Online

Introduction

Effective, credible and fair selection for surgical specialty training is vital. It has implications for patient safety, as well as personal, social, geographical and financial impacts. Face-to-face selection was cancelled for the UK 2020 national selection round due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Selection in 2021 will be conducted entirely online. Virtual selection is likely to persist beyond the COVID-19 pandemic as costs may be significantly reduced by its use.1

Virtual selection for a national higher surgical programme (specialty registrar (ST3) and above) is new territory in the UK. Patient safety must be one of the first priorities when selecting candidates.2 Surgical selection committees should look to other high-reliability organisations (HROs), such as aviation, who have already established reliable selection methods with online components, many in response to fatal or serious incidents.

There are ten recognised surgical specialties in the UK; the majority of these have competitive entry into higher (ST3+) training. Following foundation years (FY1–FY2), most surgical trainees undertake two generic core surgical training years (CT1–CT2) before applying for specialty-specific higher surgical training (ST3–ST8). The Joint College of Surgical Training (JCST), via specialty advisory committees (SAC), design this selection process. The process is subsequently managed and delivered by Health Education England (HEE). Guidelines and recommendations by the General Medical Council (GMC) and Royal College of Surgeons of England inform and influence the design process.3

Selection at ST3 is national, but specific for each surgical specialty. Candidates are given a score that, when aligned with their own preferences, determines the programme and geographical region offered. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, selection typically involved a pre-prepared self-assessment detailing time spent in specialty, procedures performed, courses or additional degrees undertaken and academic achievements. This academic focus may demonstrate commitment to a surgical career but cannot adequately assess skills or compatibility with the career in isolation. It may even select for candidates who demonstrate a drive to compete directly with colleagues, rather than those who excel at team working or developing their own surgical competencies.

The face-to-face interview element previously carried most marks (more than 90%), and included practical skills, clinical problem-solving, simulated patient interaction and presentation or research paper interpretation skills. In 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, HEE mandated that selection for most specialties would be based solely on a self-assessment score without evidence checking taking place.4 This method was not supported by most SACs.5

This paper discusses the aims and challenges of rapidly developing virtual selection methods for higher surgical training. We review existing online selection methods in healthcare, as well as those that could be adapted from other HROs.

The aims of virtual selection

Selection for higher surgical training is not an initial entry point to the medical or surgical profession. The majority of the skills and professional attributes required have already been selected for, taught or examined during undergraduate or postgraduate training. There is limited evidence that a challenging selection process improves successful candidate motivation on appointment, and then only temporarily.6

Selection has a significant role in ensuring allocation of human resources to support the National Health Service (NHS) throughout the UK. Approximately half of the medical workforce are ‘junior’ doctors who provide this service. More gateways along a training pathway allow more opportunities for reallocation of personnel.

Attrition may be built into the training pathway to both provide labour at the ‘junior’ end of the pathway and allow for underperforming candidates. However, insufficient assessment risks recruiting surgical trainees with poor career longevity potential due to clinical skills, lifestyle expectations or psychological suitability. This is an ineffective use of human resources that could be deployed earlier elsewhere in the health service, a risk for frustration and burnout, and unnecessary use of trainer time and support. In recent years, CT2 progression to completion of training in the form of a Certificate of Completion of Training (CCT), was as low as 6% for some surgical specialties.7 Run-through training is currently being trialled for some specialties as part of a limited Improving Surgical Training (IST) programme.8

There is a responsibility to the individual and their support networks for a fair, well designed selection process. The mean age of appointment at ST3 level is 29.9 Relocation for work may not be possible as family support or caring roles may take priority. There are financial implications of a loss of career progression. Candidates will already have accrued significant debt from undergraduate and postgraduate degrees, postgraduate examinations, courses and conference attendance.10

Existing mandatory assessments could be considered at virtual national selection. Passing the written (part A) and clinical (part B) Membership of the Royal College of Surgeons (MRCS) postgraduate examinations is a prerequisite to application for higher surgical training. It does not, however, currently contribute to the selection score itself. A first-time part B pass correlates with a successful national selection score.11 More than two attempts at the MRCS part B examinations also correlate with an unsatisfactory annual review of competency progression (ARCP).12

Harsh lessons were learnt following the introduction of Modernising Medical Careers (MMC) in 2003 and the Medical Training Application Service (MTAS) in 2007. Traditional local assessment and recruitment was replaced with a system intended to streamline the process and ensure posts were filled nationally. Highly qualified senior trainees, now known colloquially as the ‘lost tribe’, were unable to progress when entry criteria for higher training changed. There was a loss confidence in the system, and a reduction in trainee morale. A formal enquiry into these failings, the Tooke Report, recommended national selection centres, rather than local unstructured interviews.13 These selection principles should be incorporated into virtual selection (Table 1).

Table 1 .

Principles for national selection, adapted from Thomas, 200814

| Selection principles | Assessment domains |

|---|---|

|

|

Technical and non-technical factors for video interviewing

Video interviewing has been undertaken in the business sector for over 15 years, using generic meeting platforms including Zoom or Microsoft Teams. Specific interviewing software such as SparkHire or HireVue has additional features such as online pre-assessments to assess compatibility, intellect and personality. Structured scoring systems and automated data collection ensure there is no illegal discrimination in the process.

Video interviews should be structured to reduce bias and may be based on the exercises that would have taken place during face-to-face interviews, such as clinical scenarios or operating list planning.

Video interviews may suffer from poor synchronisation between audio and video, leading to less fluid conversations. Nonverbal communication and cues may be limited, as visualisation of the other person is only of the head and torso.15 These limitations may make simulated scenarios with patient actors difficult and unrealistic.

Candidates may be concerned that assessors are less invested in video interviews. There is the possibility for increased miscommunication, unfamiliarity with technology, and a variety of assessor experience in the virtual environment.16 Subjective assessor bias may be magnified, such as an interviewer's preference for outgoing people.

Human factors affecting assessors have been studied in face-to-face UK national selection for surgery. Examiner stress, boredom and fatigue when interviewing a large number of candidates are reduced with regular breaks and changing the scenarios being examined.17 These factors may be more pronounced with limited interaction in an online platform.

Virtual assessment methods from healthcare

Virtual specialist selection already exists in medicine, as the Multi-Specialty Recruitment Assessment (MSRA) situational judgement test. This was originally introduced in general practice (GP) as a shortlisting tool. In 2021, it will be the sole method of selection for GP and psychiatry, and a shortlisting tool for specialties including radiology, anaesthetics and ophthalmology.

The examination consists of a situational judgement test (SJT) and clinical problem-solving. The Work Psychology Group developed the SJT in line with the generic professional capabilities laid out in the GMC document, Good Medical Practice.18 The clinical problem-solving element requires knowledge of clinical guidelines particularly relevant to GP and broad medical specialties.

The MSRA is predictive for achievement at the GP final ARCP.19 The test has not been yet validated for surgical specialties. It is likely that additional practical skills and knowledge domains would need to be assessed if the MSRA is incorporated into online assessment in the future. Additionally, the burden for trainees of preparing for a further examination should be justified, particularly when the compulsory MRCS examination has predictive validity for success at ST3 interview.

Virtual assessment methods from HROs

Selection methods in HROs have mainly been developed as a result of safety concerns. Aviation and surgery cannot be compared directly, however, both share the human element and demand a similar set of attributes.

Aircrew selection during World War I relied on unstructured interviews and assessment of academic achievement. This resulted in up to 50% attrition during training through serious accidents or failure to progress. Introduction of practical tests, a flight test and psychological assessment reduced this number by half.

Current Royal Air Force (RAF) military aircrew candidates undergo assessment at a national selection centre. Approximately 100 pilots are recruited to the RAF annually from 8,000 applicants. The process is high-stakes, for both safety and the cost to the taxpayer of around £5m to train a fast-jet pilot. Candidates undergo computer-based aptitude tests of cognitive and psychomotor skills. These include hand–eye coordination, a flight instrument test assessing situational awareness, multitasking, prioritisation and spatial awareness. The overall score, corrected for age and previous flying experience, is a strong predictor of those who will complete flying training. Human factors, including situational awareness, are the main causes of air accidents, and selecting for these attributes has clear safety benefits.20

Computer-based aptitude tests have also been adopted by airline and air traffic control organisations, more recently allowing candidates to take these remotely (Figure 1). These could be directly relevant to surgery as increasingly complex robotic, arthroscopic or laparoscopic procedures must be carried out while managing teams, distraction and maintaining situational awareness.

Figure 1 .

An example of a hand–eye coordination and multitasking task, typical of those used for online pilot selection.

The majority of these assessments test cognitive and psychomotor abilities with abstract tasks. Surgical selection in the UK has trialled the use of arthroscopic or laparoscopic box simulators. A criticism of this process has been that primed candidates may ‘learn’ how to complete the limited number of pre-set tasks rather than this being a true test of psychomotor abilities or novel skill acquisition. Additionally, it does not assess important human factors such as situational awareness. Online abstract assessment of abilities may help eliminate this bias.

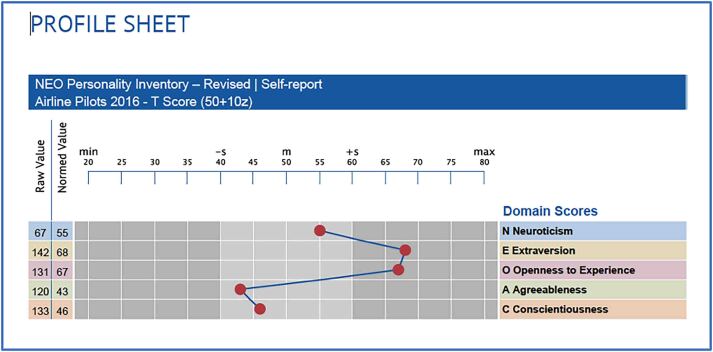

Computer-based psychometric testing has been used for decades in aviation to ensure pilot personalities are compatible with attributes for safety and career longevity. Similar testing has been introduced in the offshore oil industry, following failings resulting in the 1988 Piper Alpha oil rig fire.21 The Checklist Professional Profile (CPP) assesses specific traits and could be used to select for those relevant to surgical training such as resilience, stress tolerance, impulse control, perseverance, assertiveness, teamwork, helpfulness, empathy, autonomy and openness.22 The well-established NEO Personality Inventory test (NEO Pi-R) assesses five personality traits. Conscientiousness and neuroticism are particularly predictive of success across job roles (Figure 2).

Figure 2 .

A revised NEO personality inventory (NEO PI-R) profile. Values outside the typical range for the job profile are explored with further assessment.

Psychological assessment in commercial aviation was introduced following the 2015 German Wings flight 9525 crash.23 It is mandated by the European Aviation and Space Authority (EASA) in certain contexts including selection, return to duty, monitoring and airline captain training. It usually takes place via a video interview, is overseen by a clinical psychologist, and incorporates well established psychometric instruments with strong reliability and validity, predictive power and retest reliability. It assesses competence, emotional stability, motivation and psychological fitness, particularly following psychological trauma or illness. In surgery, resilience and psychological aptitude have been increasingly emphasised, particularly in light of increased workload, more frequent handovers, staff shortages and a decline in informal support structures.24

Conclusion

National selection for higher surgical training in the UK is competitive. As it transitions to a virtual format, the process must prioritise patient safety while being credible, impartial and fair. Many existing online selection methods, such as the MSRA, do not yet have predictive validity for trainee outcomes in surgery, and additional parameters may need to be considered. Lessons may be learnt from HROs such as aviation that require similar attributes as surgery and have safety as their priority.

References

- 1.NHS Health Education England. Health Education England Specialty Recruitment Webinar. https://specialtytraining.hee.nhs.uk/Recruitment (cited October 2020).

- 2.General Medical Council. Promoting excellence: Standards for medical education and training, March 2015.

- 3.Joint Committee on Surgical Training. https://www.jcst.org/introduction-to-training/selection-and-recruitment (cited October 2020).

- 4.NHS Health Education England. Coronavirus Information for Trainees. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/coronavirus-information-trainees (cited October 2020).

- 5.BOTA British Orthopaedic Trainees Association. BOTA position statement on changes to 2020 orthopaedic ST3 national selection. http://www.bota.org.uk (cited October 2020).

- 6.Wouters A, Croiset G, Galindo-Garre F, Kusurkar RA. Motivation of medical students: selection by motivation or motivation by selection. BMC Med Educ 2016; 16: 37. 10.1186/s12909-016-0560-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oxtoby K. The new lost tribe, vol 341. http://careers.bmj.com/careers/advice/view-article.html?id=20001503 (cited October 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Royal College of Surgeons of England. Improving Surgical Training. https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/careers-in-surgery/trainees/ist/ (cited October 2020).

- 9.Orthopaedic Interview. What Makes A Good Candidiate? https://www.orthointerview.com/The-Application/Self-Assessment.php (cited 11 October 2020).

- 10.Council of the Association of Surgeons in Training. Cross-sectional study of the financial cost of training to the surgical trainee in the UK and Ireland. BMJ Open 2017; 7: e018086. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scrimgeour DSG, Cleland J, Lee AJet al. Impact of performance in a mandatory postgraduate surgical examination on selection into specialty training. BJS Open 2017; 1: 67–74. 10.1002/bjs5.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scrimgeour D, Brennan PA, Griffiths Get al. Does the intercollegiate membership of the Royal College of Surgeons (MRCS) examination predict ‘on-the-job’ performance during UK higher specialty surgical training? Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2018; 100: 1–7. 10.1308/rcsann.2018.0153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tooke J. Aspiring to excellence: final report of the independent inquiry into modernising medical careers. MMC Inquiry 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas W. The making of a surgeon. Surgery 2008; 26: 400–402. 10.1016/j.mpsur.2008.08.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joshi A, Bloom DA, Spencer Aet al. Video interviewing: A review and recommendations for implementation in the Era of COVID-19 and beyond. Acad Radiol 2020; 27: 1316–1322. 10.1016/j.acra.2020.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones RE, Abdelfattah KR. Virtual interviews in the Era of COVID-19: A primer for applicants. J Surg Educ 2020; 77: 733–734. 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.03.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scrimgeour DSG, Higgins J, Bucknall Vet al. Do surgeon interviewers have human factor-related issues during the long day UK National Trauma and Orthopaedic specialty recruitment process? Surgeon 2018; 16: 292–296. 10.1016/j.surge.2018.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.General Medical Council. Good Medical Practice. 2013.

- 19.COVID-10 changes to specialty training recruitment, British Medical Association. https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/covid-19/bma-asks/covid-19-changes-to-specialty-training-recruitment (cited November 2020).

- 20.Paice AG, Aggarwal R, Darzi A. Safety in surgery: is selection the missing link? World J Surg 2010; 34: 1993–2000. 10.1007/s00268-010-0619-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flin R, Slaven G. The selection and training of offshore installation of managers for crisis management. HMSO 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stolk-Vos AC, Heres MH, Kesteloo Jet al. Is there a role for the use of aviation assessment instruments in surgical training preparation? A feasibility study. Postgrad Med J 2017; 93: 20–24. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2016-133984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aerospace Medical Association Working Group on Pilot Mental Health. Pilot mental health: expert working group recommendations - revised 2015. Aerosp Med Hum Perform 2016; 87: 505–507. 10.3357/AMHP.4568.2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arnold-Forster A. Resilience in surgery. Br J Surg 2020; 107: 332–333. 10.1002/bjs.11493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]