Abstract

Jejunal diverticula are a rare acquired herniation of the mucosa and submucosa through the muscularis propria. They are asymptomatic in the majority of cases; however, they can present with non-specific abdominal symptoms and rarely complicate leading to acute abdomen. Perforation usually results in symptoms and signs of acute peritonitis and it is not an identifiable aetiology of chronic pneumoperitoneum. Computed tomography scanning may identify intestinal wall oedema, air bubbles travelling through the mesentery, free intra-abdominal air and/or fluid. Radiological diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion of such pathology. We report a case of an isolated jejunal diverticulum as a cause for aseptic chronic pneumoperitoneum.

Keywords: Intestinal perforations, Jejunal disease, Pneumoperitoneum, Unexpected

Background

Small intestinal diverticula represent a rare entity with a recorded incidence of 0.06–1.3%. Jejunal diverticula are the rarest acquired pulsion diverticula and usually become more prevalent after the sixth decade of life.1 They are asymptomatic in most cases, although patients may present with a wide spectrum of chronic non-specific symptoms and complications can develop in up to 10% of cases.2 Here, we report a case of chronic pneumoperitoneum induced by an isolated jejunal diverticulum.

Case history

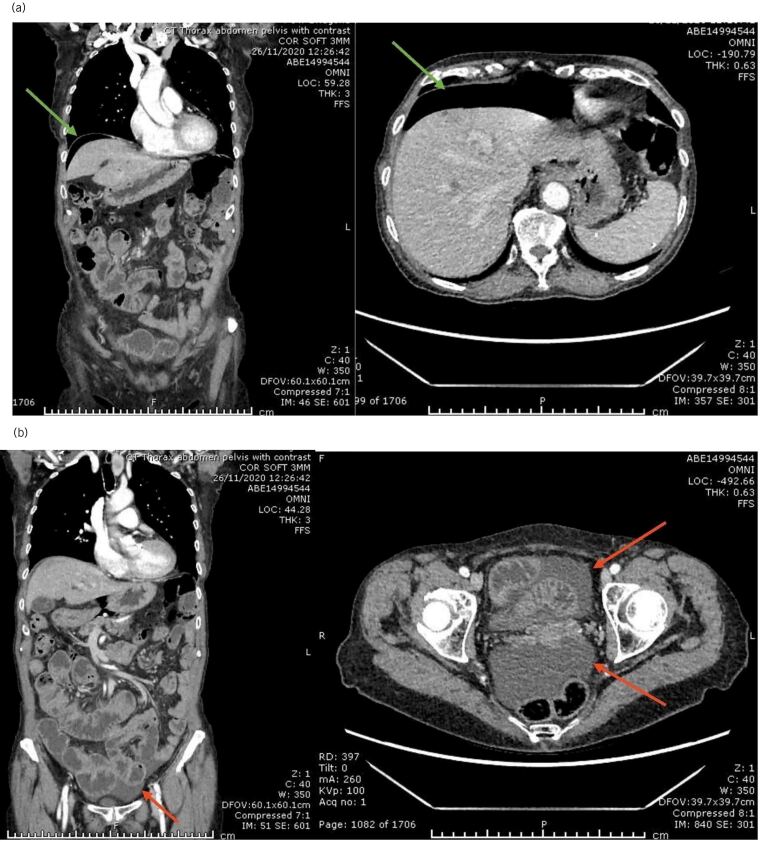

A 77-year-old woman was referred to the ambulatory emergency surgical unit with a 4-month history of non-specific abdominal pain not responding to medical treatment, considerable weight loss (10% of her body weight), diarrhoea, nausea and a few episodes of vomiting. Her background medical history was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed no constitutional signs of sepsis and her abdomen was mildly distended but soft and non-tender to palpation. Laboratory investigations were normal for levels of C-reactive protein, white cell count and all the remaining biochemical profile as well. The patient proceeded to have computerised tomography (CT) scan of her abdomen and pelvis on her first visit, which showed pneumoperitoneum with associated low-volume ascites, which raised the possibility of sealed gastrointestinal perforation (Figure 1). In the absence of any clear signs of sepsis, a strategy of ambulatory, conservative management and follow-up was chosen.

Figure 1 .

Coronal and axial computed tomography (CT) images of the abdomen: (a) pneumoperitoneum (green arrows); (b) mild pelvic collection (red arrows)

After 4 weeks, the patient presented with different pain suggesting biliary disease and ultrasonography demonstrated multiple gallstones. Once more a decision was made for conservative treatment, especially driven by the limitations of surgery available during the height of the COVID-19 crisis and the plan for clinical follow-up was maintained.

Four months after her initial presentation, the patient was seen in clinic and found to have ongoing vague abdominal symptoms with weight loss and failure to thrive. A CT colonogram was decided upon to exclude a colonic cause for her symptoms, especially malignancy. The radiologist described pneumoperitoneum and a larger volume of ascites is in comparison with the previous CT scan. There was an unusual pattern of mural gas in some loops of small bowel in the left side of the abdomen that suggested pneumatosis (Figure 2). A multidisciplinary team discussion was held and a decision to proceed with diagnostic laparoscopy reached.

Figure 2 .

Axial computed tomography (CT) sections of the abdomen (CT colonogram) showing: (a) moderate amounts of perisplenic and pelvic free fluid collections (yellow arrows); (b) jejunal bowel loop with intramural linear and cystic air loculi/collections (yellow arrow). No underlying colonic pathology was detected.

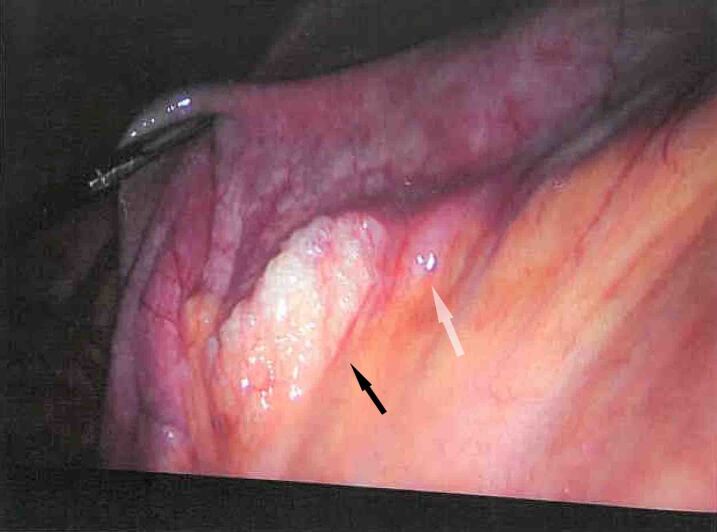

Appropriate consent was attained and at laparoscopy we used three ports as follows: a 10ml subumbilical optical port and two 5mm operating ports on both iliac fossae. Intraoperative findings revealed odourless pneumoperitoneum, moderate amount of non-turbid bile-stained serous ascites and thin fibrinous covering. We identified a jejunal diverticulum associated with mesenteric air bubbles and moderately enlarged reactive-feeling lymph nodes in the diverticular segment (Figure 3). A decision was made to proceed with a small bowel resection with a primary side-to-side anastomosis, washout of the abdomen and cholecystectomy. This was conveniently achieved using a Kocher’s subcostal incision. The patient made an uneventful postoperative recovery and was discharged home well on day 4. Histopathological examination of the resected specimens confirmed the presence of a ruptured isolated jejunal diverticulum with a breach in muscularis propria and chronic cholecystitis in the gallbladder.

Figure 3 .

Intraoperative image taken during laparoscopic exploration of the abdominal cavity showing air bubbles between the mesenteric leaflets at the site of the perforated diverticulum (black arrow) and the diverticulum at the mesenteric border of the jejunal loop (white arrow)

Discussion

Jejunal diverticula represent a rare entity with an incidence below 1% and usually occur after the sixth decade of life. They are false pulsion diverticula secondary to mucosal and submucosal herniation through muscularis propria defects in which the vasa recta penetrate the intestinal wall along the mesenteric border. The exact pathophysiology is unknown; however, it is thought to result from gastrointestinal smooth muscle dyskinesia and/or myenteric plexus dysfunction leading to uncoordinated smooth muscle activity and localised areas of high intraluminal pressure.3

Previous studies suggested that jejunal diverticula can occur as a part of underlying connective tissue disease or secondary to cocaine abuse, steroids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.4 Our patient did not have any associated comorbidities that can be related to this pathology. Jejunal diverticula are usually asymptomatic, however after identification, 29–40% can develop chronic non-specific symptoms such as flatulence, discomfort, pain, diarrhoea and malabsorption. They are difficult to identify in the general population owing to symptom overlap with other conditions. Complications such as perforation, obstruction, adhesion, fistula, peritonitis and lower gastrointestinal bleeding can occur in 10% of cases.2 Perforation usually results in symptoms and signs of acute peritonitis and it is not an identifiable aetiology of chronic pneumoperitoneum. CT scan may identify localised collection, intestinal wall oedema and inflammation, air bubbles travelling through the mesentery, free intra-abdominal air and/or fluid. In our patient, these radiological signs raised the suspicion of a perforated jejunal diverticulum as the cause of her chronic intraperitoneal free air and fluid collection. We were not distracted by the possibility of her biliary disease being the only cause for her chronic symptoms. The other radiological sign that helped us to suspect perforated jejunal diverticulosis was the suggestion of air bubbles in the small bowel mesentery.

This case illustrates a typical presentation of chronic pneumoperitoneum with persistent abdominal pain and nutritional compromise in the absence of sepsis. Conservative management was started before the diagnosis was reached and failed to relieve the patient’s symptoms.

The pathophysiology of chronic pneumoperitoneum is not fully understood. Dunn and Nelson postulated that the distended diverticular mucosa may function as a semipermeable membrane allowing transmural gas equilibration.5 In our patient’s case, the condition was chronic and negatively affecting her quality of life. She was robust enough to contemplate surgery, the benefits of resection outweighed the risk and she was managed surgically via small bowel resection of the affected segment and had an uneventful recovery.

Conclusion

In summary, our case report highlights the importance of being aware of the possibility of perforated jejunal diverticula as a possible source of chronic pneumoperitoneum causing chronic non-specific abdominal pain, diarrhoea and unexplained weight loss. The surgical option of segmental resection and primary anastomosis was beneficial in this patient. However, calculating the risk-to-benefit ratio remains the mainstay of the management plan, which, as ever, should be tailored to each patient’s general condition and fitness with appropriate counselling and consent.

References

- 1.Gurala D, Idiculla PS, Patibandla Pet al. Perforated jejunal diverticulitis. Case Rep Gastroenterol 2019; 13: 521–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Syllaios A, Koutras A, Zotos PAet al. Jejunal diverticulitis mimicking small bowel perforation: case report and review of the literature. Chirurgia (Romania). 2018; 113: 576–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nigam A, Gao FF, Steves MA, Sugarbaker PH. Acute abdomen caused by a large solitary jejunal diverticulum that induced a midgut volvulus. report of a case. Int J Surg Case Rep 2020; 74: 109–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sehgal R, Cheung CX, Hills Tet al. Perforated jejunal diverticulum: a rare case of acute abdomen. J Surg Case Reports 2016; 2016: 521–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunn V, Nelson JA. Jejunal diverticulosis and chronic pneumoperitoneum. Gastrointest Radiol 1979; 4: 165–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]