Abstract

Introduction

Early diagnosis is key to managing scaphoid fractures effectively. Computed tomography (CT) imaging can be effective if plain radiographs are negative. With increasing pressure on face-to-face clinics, consultant-led virtual fracture clinics (VFCs) are becoming increasingly popular. This study evaluates the management of patients with suspected scaphoid fractures using a standardised treatment protocol involving CT imaging and VFC evaluation.

Methods

The study was conducted at a busy district general hospital. The pathway began in February 2018. Patients presenting to the emergency department with a clinically suspected scaphoid fracture but an indeterminate radiograph had a CT scan, which was then reviewed in the VFC. Patients with a confirmed fracture were seen in a face-to-face clinic; patients without a confirmed fracture were discharged. Patient pathway outcome measures were analysed pre- and post-pathway, and a cost analysis was performed.

Results

A total of 164 pre-pathway patients (93%) were given a face-to-face fracture clinic appointment; 76 were discharged after their first visit. Nine patients seen in clinic had a CT scan and were discharged with no fracture. If these patients had been referred to the VFC, had CT scans and been directly discharged, it would have saved £1,629. A total of 41 patients from the post-pathway group (37%) had a CT scan and were discharged from the VFC. Avoiding face-to-face clinic appointments saved £7,421. Extrapolating, the annual savings would be £29,687.

Conclusions

This study shows that a VFC/CT pathway to manage patients with a suspected scaphoid fracture is cost-effective. It limits face-to-face appointments by increasing use of CT to exclude fractures.

Keywords: Trauma, Scaphoid, Computerised tomography, Virtual fracture clinic

Introduction

The scaphoid is the most commonly fractured carpal bone. Patients present with anatomic snuffbox tenderness.1 These fractures are especially common in young men, with peak incidence in the second and third decades.2 The retrograde blood supply from the dorsal carpal branch and superficial palmar arch predisposes to the development of fracture non-union; this risk increases with proximal pole fractures.3

The majority of radiologically confirmed scaphoid fractures are stable and minimally displaced. They are treated conservatively with a plaster cast to immobilise the wrist for 6–8 weeks, followed by clinical assessment of healing, with up to 12 weeks of cast immobilisation if required.4 The union rate for scaphoid fractures is 85–90%,5 but the risk of non-union increases if there is a delay in diagnosis.

Because there is an incidence of false negative radiographs following scaphoid injury,6 follow-up in fracture clinic for repeat examination and imaging is required if a scaphoid fracture is clinically suspected.

Clinically suspected but radiologically negative or ambiguous scaphoid fractures are treated with immobilisation, resulting in some cases of unnecessary immobilisation where no fracture ever occurred.6

Early confirmed diagnosis and appropriate treatment are key to minimising non-union, malunion and unnecessary immobilisation, which can lead to stiffness, and to avoiding long-term complications such as avascular necrosis and wrist arthritis.

A retrospective study found that early (one to two weeks) computed tomography (CT) scanning has been shown to improve the time to definitive diagnosis.7 CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have been shown to be equally effective in identifying or ruling out scaphoid fracture. MRI has 98% sensitivity, 99% specificity and 96% accuracy. CT has 94% sensitivity, 96% specificity and 98% accuracy.6,8,9 In the studied hospital, CT scans are readily available but there can be a delay in obtaining even urgent MRI scans.

There is increasing pressure on face-to-face clinics. In a typical fracture clinic, a wide range of orthopaedic injuries are referred to a team consisting of orthopaedic surgeons, nurses, plaster room technicians, and other members of the multidisciplinary team. Use of emergency department protocols for stable injuries that may be treated conservatively is growing, with follow-up successfully implemented via a virtual fracture clinic (VFC).10 In such clinics, which are often consultant-led, management decisions can be made for many patients without the need for face-to-face appointments.

In the studied VFC, a consultant reviews the emergency department notes and imaging to make a management decision. The decision is communicated by telephone to the patient by a VFC physiotherapist, and the patient is sent relevant written information.

With COVID-19 social distancing restrictions limiting the numbers of patients we can see in face-to-face clinics, being able to manage patients remotely is beneficial.

The baseline practice in the studied district general hospital was as follows: all patients with clinically suspected scaphoid fractures (defined as tenderness over the anatomic snuffbox or scaphoid tubercle, or pain on axial loading of the thumb metacarpal) and negative radiographs are immobilised in a scaphoid cast and subsequently referred to a face-to-face clinic. In clinic, examination is repeated and the patient sent for a CT scan if indicated, with further face-to-face follow-up for results. This leads to a large number of patients without fractures attending face-to-face clinics.

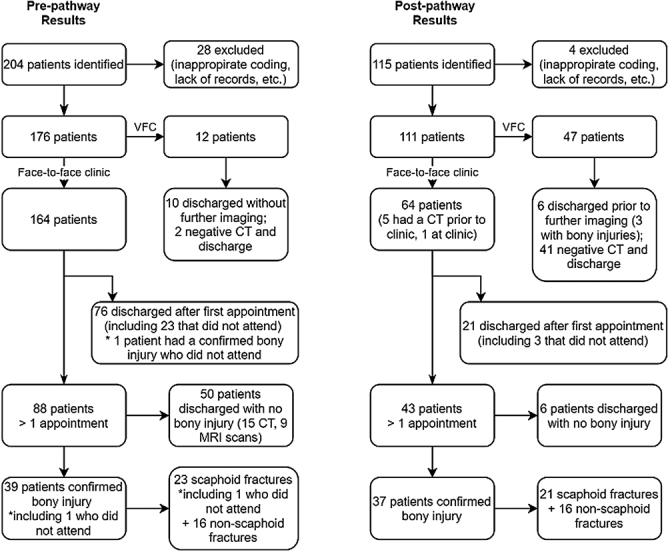

A CT/VFC pathway was introduced with the aim of reducing unnecessary face-to-face clinic attendance. Patients with clinically suspected scaphoid fractures but negative radiographs at first presentation are referred directly for CT, with the results reviewed in a VFC. Patient examination is performed by emergency department doctors and practitioners, with the decision to refer ultimately made by an emergency department consultant. Where possible, scanning is performed on the day in the emergency department. Images are reviewed in the VFC by an orthopaedic consultant. If bony injury is confirmed by the CT scan, patients are followed up in a face-to-face clinic. If no injury is identified on the CT scan, patients are discharged from the VFC without the need to attend a face-to-face clinic; they attend the plaster room directly to have their cast removed, with a removable splint provided if necessary (Figure 1).

Figure 1 .

Pre- and post-intervention pathways

This study assesses the effect on face-to-face clinic attendance after implementing the CT/VFC pathway in a busy district general hospital for patients attending the emergency department with a suspected scaphoid fracture. Patient re-attendance (to determine safety of the pathway) and cost implications were analysed.

Methods

This study was a clinical audit of practice, and therefore research ethics committee approval was not required. It was registered with the hospital’s audit department. The pathway evolved gradually, so we chose a pre-pathway period a year before its final form, and a post-pathway period once we felt the pathway was fully established.

Pre-pathway data were for February to May 2017. The pathway was introduced in February 2018. Post-pathway data were for May to July 2018. Patients coded diagnostically in the emergency department database with the terms ‘scaphoid’ or ‘wrist’ (with ‘injury’ or ‘fracture’) were identified, and those with suspected scaphoid injuries were included. Data were taken from VFC records and electronic patient records, including clinical notes and imaging.

A cost analysis was conducted in collaboration with the trust head of costing. Costs are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1 .

Costs of services from trust head of costing

| Service | Cost |

|---|---|

| Clinics | |

| Consultant-led face-to-face first clinic | £216.51 |

| Consultant-led face-to-face follow-up clinic | £182.78 |

| Consultant-led first VFC | £49.41 |

| Consultant-led VFC follow-up | £35.49 |

| Imaging | |

| CT scaphoid | £85.20 |

Results

We identified 204 patients presenting with suspected scaphoid injury between February and May 2017 (pre-pathway). We identified 115 patients presenting with suspected scaphoid injury between May and July 2018 (post-pathway) (Table 2).

Table 2 .

Outcomes for patients in pre- and post-pathways

| Pre-pathway | % | Post-pathway | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number identified | 204 | 115 | ||

| Total number included | 176 | 111 | ||

| Face-to-face follow-up | 164 | 93.2 | 64 | 57.7 |

| Did not attend | 23 | 14.0 | 3 | 4.7 |

| VFC follow-up | 12 | 6.8 | 47 | 42.3 |

| CT imaging from VFC | 2 | 1.1 | 41 | 36.9 |

| Negative scans from VFC | 2 | 1.1 | 41 | 36.9 |

Of the 204 pre-pathway patients, 117 (57.4%) were female. Of the 115 post-pathway patients, 65 (56.5%) were female. The average age was 33 years for the pre-pathway patients and 35 years for the post-pathway patients.

A total of 28 of the 204 pre-pathway patients were excluded (inappropriate coding, lack of patient records), giving a total of 176 pre-pathway patients. Of these, 164 (93.2%) had a face-to-face clinic appointment, and 12 (6.8%) had no face-to-face follow-up but were managed through the VFC. Ten of these 12 were subsequently discharged from the VFC without further imaging; the other 2 had CT scans, both of which were negative for fracture, and were then discharged from the VFC.

A total of 23 patients (14.0%) did not attend their appointments and were discharged without being seen. Of the 164 patients (32.3%) who had a face-to-face clinic appointment, 53 were discharged after their first appointment. Of these, 9 had a CT scan (8 on the day of the appointment), all of which showed no fracture. Fifty of the 164 patients (30.5%) had more than 1 clinic appointment before being discharged with no bony injury identified; 15 of these had a CT scan, and 9 an MRI scan.

Thirty-nine of the 164 patients (23.8%) had a confirmed bony injury, of which 23 (14.0%) were scaphoid fractures (1 patient with a scaphoid fracture did not attend their appointment and was excluded). Five of these were diagnosed with a CT scan on the day of their clinic appointment. The other 16 (9.8%) had non-scaphoid bony injuries (11 distal radius fractures, 5 carpal bone fractures), of which 3 were diagnosed by CT scan and 2 by MRI. These results are summarised in Figure 2.

Figure 2 .

Pre- and post-pathway results

Four of the 115 were excluded (missing notes, follow-up at another trust), giving a total of 111 patients. Of these, 64 (57.7%) had face-to-face clinic appointments, and 47 (42.3%) were managed purely through the VFC. Of these 47, 41 (87.2%) had a negative CT scan and were discharged without face-to-face appointments. The other 6 of the 47 (12.8%) were discharged with the decision that a scan was not required. Three of these patients were found to have non-scaphoid bony injuries (radial styloid, radial epiphyseal and distal radius fractures, managed non-operatively).

Twenty-one of the 64 patients (32.8%) booked for face-to-face clinic appointments were discharged after 1 visit or did not attend their appointments (3 patients). Six of these patients had negative CT scans. Forty-three of the 64 patients (67.2%) had more than 1 clinic appointment.

Of the 64 patients who had a fracture clinic appointment, 37 had a confirmed bony injury; 16 had fractures of bones other than the scaphoid (8 distal radius fractures, 7 carpal bone fractures, 1 thumb metacarpal fracture). Ten of these were identified with a CT scan before their first appointment. Twenty-one of the 64 patients (32.8%) had scaphoid fractures (Figure 2). Six of these were diagnosed only after a CT scan. Two patients had a CT scan to confirm non-union and one for preoperative planning.

Two patients discharged from VFC (both after negative CT scans) presented again for ongoing pain, 1 after a week and 1 after 18 weeks. They both received further examination and radiographs of their wrist, hand or thumb, which showed no fracture, and were subsequently discharged without complication.

From the pre-pathway data, the cost of seeing the 53 patients discharged after their first clinic appointment, including the cost of the 9 negative CTs, was £14,190.42. The 23 patients who did not attend their appointments cost £4,979.73. If these patients had been managed through the VFC, including having a CT scan, the saving would have been £1,629.18.

From the post-pathway data, the additional cost for the 41 patients having a CT scan and then being discharged from the VFC was £4,948.29. If these patients had had face-to-face clinic appointments and CT scans and then been discharged, the cost would have been £12,370.11. Therefore, the introduction of the CT pathway saved a total of £7,421.82. Extrapolating, the annual savings would be £29,687.28.

Discussion

The study shows that implementing a CT/VFC pathway for injuries where scaphoid fracture is suspected reduces the number of face-to-face clinic appointments and leads to a definitive plan and diagnosis for patients sooner. Patients with bony injuries are identified early and manged appropriately and safely (two re-attendances were discharged with no significant injury missed). The unit’s experience was that a lot of patients seen in the emergency department with a wrist injury and a normal radiograph were referred to the orthopaedic team as a possible scaphoid fracture. Before the CT/VFC pathway, it was not possible to discharge these patients from the VFC and they were seen in clinic for further evaluation.

Undoubtably more patients will have had CT scans than in the traditional fracture clinic model. CT was used rather than MRI because in this unit a CT may be attained when a patient attends the emergency department and does not require a radiologist’s report before review in the VFC. The cost of the additional CT scans was outweighed by the reduction in number of face-to-face fracture clinic appointments. The CT department was able to accommodate these additional patients without impacting on waiting times for other patients. A small number of patients were referred to the face-to-face clinic following a CT scan, rather than VFC. In these cases, the radiographs were highly suspicious of a scaphoid fracture (and thus the patients required clinic follow-up); however, CT would better show the fracture pattern and the scan was performed before their first appointment in clinic. This was a mild variant of the pathway.

The results show significant cost savings with the pathway. The NHS trust is on an aligned incentive contract with the local commissioners, so savings are to the local health economy and do not impact on the trust’s income.

A retrospective study in a UK district general hospital has shown that early (one to two weeks) CT imaging of patients with negative radiographs but clinical suspicion of scaphoid injury (anatomical snuffbox tenderness, pain on axial loading of the thumb, tenderness over the scaphoid tubercle) can identify bony injury early and help to avoid unnecessary cast immobilisation.7 In the study, 31% of 102 patients with no abnormality on their radiographs had a fracture found on their CT scans, 74% of which were scaphoid fractures. The 69% of these patients with no bony injury would initially have been treated, unnecessarily, with immobilisation. By using CT where a scaphoid fracture is clinically suspected but not seen on a radiograph, in conjunction with a VFC, we have shown we can reduce the number of clinic attendances and enable earlier definitive diagnosis and patient management; this is cost-effective.

There are a number of limitations to our study. Although CT scanning is cheaper and more readily available than MRI scanning, it exposes patients to radiation and is less sensitive in diagnosing soft tissue wrist injuries.11 Scanning more patients means more patients are exposed to radiation as a result of the pathway. This must be considered when evaluating the benefit of an early diagnosis and avoiding a period of unnecessary cast immobilisation.

We did not evaluate patient satisfaction at being treated by telephone rather face-to-face appointments. A study evaluating satisfaction in patients with radial head and neck fractures, however, found that despite most patients (182 of 202) being managed through a VFC and not seeing a clinician, satisfaction rates were high (87–96%).12 A further study found similarly high satisfaction rates in a patient group with clavicle fractures treated via a VFC, with the majority discharged without a face-to-face clinic appointment.13 These studies suggest patients are satisfied with early knowledge of their diagnosis, and prompt and appropriate treatment, despite lack of an in-person consultation with a clinician, and managing appropriate patients via a VFC is satisfactory. A follow-up study surveying the patients from this study would help support this conclusion further.

Conclusions

This study supports the use of CT scanning early in conjunction with a VFC in the management of suspected scaphoid injuries with inconclusive radiographs at first presentation. We believe the pathway is safe and cost-effective and reduces the number of patients needing face-to-face appointments.

References

- 1.Makhni MC, Makhni EC, Swart EF, Day CS. Orthopedic Emergencies. Cham: Springer; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hove LM. Epidemiology of scaphoid fractures in Bergen, Norway. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1999; 33: 423–426. 10.1080/02844319950159145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grewal R, Lutz K, MacDermid JC, Suh N. Proximal pole scaphoid fractures: a computed tomographic assessment of outcomes. J Hand Surg 2016; 41: 54–58. 10.1016/j.jhsa.2015.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alshryda S, Shah A, Odak Set al. Acute fractures of the scaphoid bone: systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgeon 2012; 10: 218–229. 10.1016/j.surge.2012.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hambidge JE, Desai VV, Schranz PJet al. Acute fractures of the scaphoid: treatment by cast immobilisation with the wrist in flexion or extension?. J Bone Joint Surg 1999; 81: 91–92. 10.1302/0301-620X.81B1.0810091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaebler C, Kukla C, Breitenseher Met al. Magnetic resonance imaging of occult scaphoid fractures. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 1996; 41: 73–76. 10.1097/00005373-199607000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen Q, Chaudhry S, Sloan Ret al. The clinical scaphoid fracture: early computed tomography as a practical approach. Ann R Coll Surg Eng 2008; 90: 488–491. 10.1308/003588408X300948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel NK, Davies N, Mirza Z, Watson M. Cost and clinical effectiveness of MRI in occult scaphoid fractures: a randomised controlled trial. Emerg Med J 2013; 30: 202–207. 10.1136/emermed-2011-200676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mallee W, Doornberg JN, Ring Det al. Comparison of CT and MRI for diagnosis of suspected scaphoid fractures. JBJS 2011; 93: 20–28. 10.2106/JBJS.I.01523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vardy J, Jenkins PJ, Clark Ket al. Effect of a redesigned fracture management pathway and ‘virtual’ fracture clinic on ED performance. BMJ Open 2014; 4. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cockenpot E, Lefebvre G, Demondion Xet al. Imaging of sports-related hand and wrist injuries: sports imaging series. Radiology 2016; 279: 674–692. 10.1148/radiol.2016150995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jayaram PR, Bhattacharyya R, Jenkins PJet al. A new ‘virtual’ patient pathway for the management of radial head and neck fractures. J Shoulder Elb Surg 2014; 23: 297–301. 10.1016/j.jse.2013.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhattacharyya R, Jayaram PR, Holliday Ret al. The virtual fracture clinic: reducing unnecessary review of clavicle fractures. Injury 2017; 48: 720–723. 10.1016/j.injury.2017.01.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]