Abstract

Background:

The lack of health education resources specific to people with disabilities contributes to disparities in outcomes. Developing user-centered materials with representative images tailored to people with disabilities could help improve knowledge and outcomes.

Objective:

As a first step in developing an online sexual health resource for adolescents with physical disabilities, we sought end-user feedback to create illustrated characters for use in educational materials.

Methods:

Two styles of characters were developed by the research team, which included a professional disability artist. Verbal and online survey feedback was obtained at the Spina Bifida Association’s Clinical Care Conference. A new image was created incorporating initial feedback. The new image and favored image from the first round were then tested through an online survey advertised on the Spina Bifida Association’s Instagram story feed. Open-ended comments were organized by categories and overlapping themes.

Results:

Feedback was obtained from 139 audience members and 25 survey respondents from the conference and 156 Instagram survey respondents. Themes included depiction of disability, non-disability diversity, other physical appearance, emotional response, and design style. Most frequently, participants suggested inclusion of character with a range of more accurately depicted mobility aids and inclusion of characters without mobility aids. Participants also wanted a larger, more diverse group of happy, strong people of all ages.

Conclusions:

This work culminated in the co-development of an illustration that represents how people impacted by spina bifida view themselves and their community. We anticipate that using these images in education materials will improve their acceptance and effectiveness.

Introduction

There is increasing attention to the pervasive disparities in medical outcomes for minority populations. Appropriately, there is a push to improve representation in all aspects of medicine, such as recruiting providers from under-represented minority communities, educating providers, and creating medical educational materials that reflect the diversity of patients.1-5 However, most of these efforts have focused on improving diversity based on race or ethnicity. While certainly important, these efforts have typically neglected one of the largest minority populations in the United States today: those with disabilities.4 Approximately 61.1 million (or 26% Americans) live with a disability, most commonly a physical disability. People with disabilities are more likely to have poor health outcomes and difficulty with health care access.6

The current lack of health educational resources tailored to people with disabilities contributes to this health disparity. Tailored educational resources have been demonstrated to be more effective at improving patient understanding and changing behavior compared to generic resources.7-12 Despite its importance to overall long-term health and wellbeing, to our knowledge, there are no readily accessible comprehensive sexual and reproductive health education materials tailored to adolescents with disabilities. This may contribute to lower use of contraception, less routine gynecologic care, and increased risk of sexually transmitted infections, sexual dysfunction, sexual abuse, and unintended pregnancies compared to the general population.13-23

To address this disparity, our team is creating an educational website with a series of short videos about sexual and reproductive health topics specific to adolescents with physical disabilities. This website will first be tailored specifically to adolescents with spina bifida, the most common congenital defect of the spine and congenital cause of a physical disability. Spina bifida is caused by incomplete closure of the neural tube within the spine during fetal development. This can result in a wide range of physical disabilities, alterations in the function of the bladder, bowel, and genital organs, and can be associated with varying degrees of developmental disability. The website will later be expanded to adolescents with other physical disabilities, such as those with cerebral palsy and spinal cord injuries. As a first step towards user-centered design of this website, we sought stakeholder feedback to design and refine the illustrated characters to be used in the educational videos for the website. We hypothesized that stakeholders would prefer characters with a range of assistive devices.

Methods

This study was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board (HUM00218858).

Project Overview

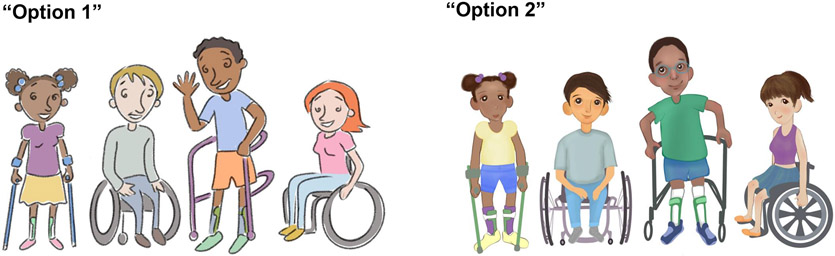

The project leads (JW and CS) worked with a professional disability artist (JR) to create two initial styles of illustrations of a group of adolescents with physical disabilities (Figure 1). The illustrations were iteratively refined based on two rounds of stakeholder testing. First, both verbal and online survey feedback was elicited from attendees of the 2022 Spina Bifida Association’s Clinical Care Conference ("Round 1"). The Spina Bifida Association is the national advocacy group for people affected by spina bifida. Based on this feedback, a new image was created and the survey instrument was refined. Next, the images were tested by “followers” of the Spina Bifida Association’s social media account (“Round 2”). The participants were asked to compare the new picture to the favorite picture from Round 1 (Figure 2). This feedback was used to develop the final image (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Round 1 Illustrations

Figure 2.

Round 2 Illustrations

Figure 3.

Final Illustration

Round 1

The 2022 Spina Bifida Association’s Clinical Care Conference was attended by 139 people, including multidisciplinary providers who care for people with spina bifida, parents of people with spina bifida, people with spina bifida, and other advocates. Prior to this conference, an online survey instrument was developed and pre-tested with two young adults (Appendix 1). At the conference, JW and CS introduced the study to the audience, displayed the images on the projection screen, and asked participants first to vote on their favorite image by raise of hand (Figure 1). Next, they were invited to share their impression and suggestions for each image through verbal feedback or by completing the online Google Forms survey. Twenty-five conference attendees completed the online survey item. A scribe took notes summarizing all feedback.

After this analysis, the results were reviewed with the research team. The artist created a new illustration responding to the critiques.

Round 2

In Round 2, followers of the Spina Bifida Association’s Instagram account were asked to give feedback on the favorite picture from Round 1 (“Option 2”) compared to the newly developed picture (“Option 1”) (Figure 2). The online survey instrument used in Round 1 was refined to include more open-ended questions and fewer quantitative questions, which were perceived as less informative (Appendix 2). It was pre-tested with a group of stakeholders. To keep the survey completely anonymous, no identifiable information was collected. As a result, it was feasible for participants to complete the survey more than once.

The online survey was advertised on the Spina Bifida Association’s Instagram “Story Feed” a total of 3 times between 7/20/2022 and 8/4/2022. Instagram was chosen as most of the Spina Bifida Association’s younger followers participate on Instagram compared to other social media outlets. The survey was open to anyone interested. It was closed on 8/18/2022.

Data Analysis

Qualitative verbal and survey results were reviewed with the research team. If a participant mentioned two distinct critiques in the same comment (e.g., feedback on both the depiction of wheelchairs and their preference for color), they were separated into distinct comments. Comments that were incomplete or not constructive (e.g., “na”) were excluded. Similar comments were then coded into categories based on their underlying directive. For example, comments stating “more variations in weight” and “add different shapes and sizes” were grouped under the category “add diversity of body type.” The frequency of each category for each image option were tabulated. Next, the categories of comments were coded into overlapping themes. For example, the categories of “show a person with just braces/orthotics” and “show a person without an assistive device” were combined under the theme of “depiction of disability.” As they were more limited, the verbal comments were listed verbatim and the themes identified.

Quantitative survey data was analyzed using Stata version 14. For both surveys, the frequency of the multiple-choice item was tabulated for each image. The first survey included Likert scales to evaluate each image, while the second used dichotomous questions. To compare the results, the differences between participant’s evaluations of each image were analyzed using Chi-square.

Results

Round 1

Voting by raising hands at the Spina Bifida Association’s Clinical Care Conference, the vast majority of attendees at the Spina Bifida Association’s Clinical Care Conference preferred Option 1 (Figure 1). Twenty-five people completed the online survey, of whom most (20, 80%) were older than 30 and were health care providers (16, 64%) or parents of a child with spina bifida (5, 20%) (Table 1). Of these respondents, 14 (56%) preferred Option 1 and 11 (44%) preferred Option 2. Despite preferring Option 1 overall, respondents felt by comparison Option 2 generally looked somewhat more like them (p=0.20), other people with spina bifida their age, people with a physical disability (p=0.08), and like people with spina bifida (p=0.04) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Round 1 and 2 Survey Participant Demographics.

| Round 1 | Round 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship to Spina Bifida Association |

n = 25 | n = 154 | ||

| Spina Bifida | 2 (8%) | Spina Bifida | 81 (52.6%) | |

| Parent of Child with Spina Bifida | 5 (20%) | Parent of Child with Spina Bifida | 63 (40.9%) | |

| Provider | 16 (64%) | Provider | 3 (1.9%) | |

| Other | 2 (8%) | Other | 7 (4.5%) | |

| Age of Participant or Participant’s Child (if Parent) |

n = 25 | n = 155 | ||

| - | - | < 8 years | 21 (13.5%) | |

| - | - | 8-12 | 14 (9%) | |

| ≤17 | 0 (0%) | 13-17 | 25 (16.1%) | |

| 18-24 | 1 (4%) | 18-22 | 20 (12.9%) | |

| 25-30 | 4 (16%) | >22 | 71 (45.8%) | |

| >30 | 20 (80%) | n/a (provider) | 4 (2.5%) | |

Table 2.

Round 1 Likert Scale/Multiple Choice Survey Item Responses.

* Items regarding the clarity of each survey item excluded.

| Survey Item | Option 1 | Option 2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Which picture do you like best? | 14 (56%) | 11 (44%) | - | |

| Do you feel these characters are people like you? | n = 23 | n = 22 | 0.20 | |

| 1 (not at all) | 5 (21.7%) | 3 (13.6%) | ||

| 2 | 2 (4.3%) | 1 (4.5%) | ||

| 3 | 4 (17.4%) | 2 (9.1%) | ||

| 4 | 7 (30.4%) | 10 (45.5%) | ||

| 5 (very much) | 6 (26.1%) | 6 (27.3%) | ||

| Do you feel like these characters show what you and the people with spina bifida your age look like? |

n = 22 | n = 21 | 0.67 | |

| 1 (not at all) | 0 (0%) | 9 (0%) | ||

| 2 | 2 (9.1%) | 2 (9.5%) | ||

| 3 | 3 (13.6%) | 4 (19%) | ||

| 4 | 8 (36.4%) | 9 (42.9%) | ||

| 5 (very much) | 9 (40.9%) | 6 (28.6%) | ||

| Do you feel this shows what it is like to have a physical disability? |

n = 21 | n = 21 | 0.08 | |

| 1 (not at all) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| 2 | 1 (4.7%) | 1 (4.8%) | ||

| 3 | 2 (9.5%) | 1 (4.8%) | ||

| 4 | 10 (47.6%) | 9 (42.9%) | ||

| 5 (very much) | 8 (38.1%) | 10 (47.6%) | ||

| Do you feel this shows what it looks like to have spina bifida? |

n = 22 | n = 21 | 0.04 | |

| 1 (not at all) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| 2 | 2 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| 3 | 3 (13.6%) | 2 (9.5%) | ||

| 4 | 8 (36.4%) | 4 (61.9%) | ||

| 5 (very much) | 9 (40.9%) | 6 (28.6%) | ||

| What age people do you think would like to watch a video using these characters (check all that apply) |

n = 25 | n = 24 | - | |

| 7-10 years | 13 (52%) | 13 (54.2%) | ||

| 11-13 years | 14 (56%) | 14 (58.3%) | ||

| 14-17 years | 2 (8%) | 3 (12.5%) | ||

| 18 and older | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| All ages | 4 (16%) | 5 (20.8%) | ||

Analysis of the open-ended survey questions and verbal feedback during the conference identified four themes, including “depiction of disability,” “other physical appearance,” “non-disability diversity,” and “design style” (Table 3). Most comments regarding “depiction of disability” focused on the importance of including characters with a wider range of abilities. This meant including both people using a wider range of assistive devices and “people without outward signs of a disability.” Participants appreciated the strong upper bodies on the wheelchair users in Option 1 as they accurately reflected “people in manual wheelchairs.” Comments regarding the character’s “other physical appearance” focused on the body type of the characters. In particular, they felt the characters were all too skinny. As one person commented, “People with spina bifida tend to gain weight as they get older.” Survey and conference participants also felt the characters in Option 1 looked younger than adolescents. Related to the theme “non-disability diversity,” many commented on the importance of including characters with a wider range of races. As a survey participant stated, “Spina bifida is more common in Hispanics. Include a Hispanic youth.” One survey respondent also requested wider range of genders. Overall, verbal and survey participants preferred the more abstract “design style” of Option 1 compared to Option 2, but appreciated the deeper colors of Option 2.

Table 3.

Theme Definitions and Examples.

| Theme | Representative Categories (Sub- Themes) |

Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depiction of disability |

|

How accurately disability, as experienced by people living with spina bifida, is portrayed | “Add a person who uses a walker. I think everyone’s mobility needs should be represented. Also add someone that just uses braces, nothing else in addition.” |

| Other physical appearance |

|

Portrayal of the character’s appearance not specific to disability | “Everyone is thin- no representation of different weights.” |

| Non-disability diversity |

|

Portrayal of the range of people with spina bifida | “Add my daughter…Asian” |

| Emotional response |

|

How the image made participants feel | “The blond girl looks like me!” |

| Design style |

|

Artistic details of the images | “The facial expressions are friendlier than the other option.” |

The team met and discussed the development of a new illustration based on the feedback. Priority was given to comments that recurred most frequently. Specifically, the team determined the new illustration should include characters with a range of abilities, including one person without an obvious disability. The team also discussed including characters with different body types, with the characters in chairs continuing to have strong upper bodies and skinnier legs, and different races, including a Latinx character. Finally, the team agreed the new illustration should use stronger colors. The artist then incorporated these changes to produce a new image (Figure 2 “Option 1”) that would be compared to the favored image from Round 1 (Figure 2 “Option 2”).

Round 2

A total of 156 responses to the survey on the Spina Bifida Association’s Instagram account were collected. The majority of respondents had spina bifida (81, 52.6%) or were a parent of a child with spina bifida (63, 40.9%) (Table 1). Over half of participants or children of a parent participant were adolescents or young adults [60 (38.6%) 17 years or younger, 20 (12.9%) 18-22].

A total of 124 (79.5%) respondents preferred Option 1 and 33 (21.2%) respondents preferred Option 2, with one person voting for both options (Table 4). Participants were significantly more likely to feel the characters in Option 1 “look kind of like [them] (or [their] child)” (75.5% for Option 1 versus 49.3% for Option 2, p<0.05). They more strongly felt the characters of both images “look kind of like other people you know with Spina Bifida” (92.3% for Option 1, 81.6% for Option 2, p<0.05).

Table 4.

Round 1 Coding of Responses to Open-Ended Survey Item “Do you have any comments, feedback, or suggestions about this picture or these characters?” and Oral Feedback.

| “Do you have any comments, feedback, or suggestions about this picture or these characters?” | ||

|---|---|---|

| Comment Category | Option 1 Frequency | Option 2 Frequency |

| n = 6 | n = 5 | |

| Theme: Depiction of Disability | ||

| Online Survey Responses | ||

| Show person with just braces/orthotics | 4 | 1 |

| Show person without any assistive device | 1 | 1 |

| Verbatim Overall Verbal Feedback | ||

| “Include people without obvious outward signs of a disability.” | ||

| “People in manual wheelchairs have a strong upper body. I like that Option 1 reflects that.” | ||

| “Older people with spina bifida don’t tend to use walkers.” | ||

| Theme: Other Physical Appearance | ||

| Online Survey Responses | ||

| Add variation in body type | 2 | 2 |

| Characters appear too young | - | 1 |

| Verbatim Overall Verbal Feedback | ||

| “People with Spina Bifida tend to gain weight as they get older. They shouldn’t all look so skinny.” | ||

| “The people in Option 1 look like kids, not adolescents.” | ||

| Theme: Non-Disability Diversity | ||

| Online Survey Responses | ||

| Add ethnic diversity | 1 | - |

| Add additional genders | - | 1 |

| Verbatim Overall Verbal Feedback | ||

| “Spina bifida is more common in Hispanics. Include a Hispanic youth.” | ||

| Theme: Design Style | ||

| Characters look more realistic and relatable | - | 1 |

| Make colors brighter/deeper | - | 1 |

| Change facial features | - | 1 |

Analysis from the three open-ended survey questions coded into 5 themes (Table 5): “depiction of disability,” “non-disability diversity,” “other physical appearance,” “emotional response,” and “design style.”

Table 5.

Round 2 Multiple Choice Survey Item Responses.

| Survey Item | Option 1 | Option 2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Which picture do you like best? | 124 (79.5%) | 33 (21.2%) | ||

| Do any of the people in this picture look kind of like you (or your child) |

n = 155 | n = 152 | <0.05 | |

| Yes | 117 (75.5%) | 75 (49.3%) | ||

| No | 38 (24.5%) | 77 (50.7%) | ||

| Do any of the people in this picture look kind of like other people you know with spina bifida? |

n = 155 | n = 152 | <0.05 | |

| Yes | 143 (92.3%) | 124 (81.6%) | ||

| No | 12 (7.7%) | 28 (18.4%) | ||

Similar to Round 1, comments regarding the “depiction of disability” were most common. Participants appreciated that both pictures showed “most of the devices people would use.” Many expressed that they appreciated that Option 1 included “a child without [a mobility device]” as it represented people with “‘invisible’ disabilities.” As one person stated, “I personally can walk without assistance and I like that it is represented here.” They criticized Option 2 for not including a person without an assistive device. To improve the final illustration, they recommended further expanding the abilities and assistive devices of the characters and adding more people without assistive devices. Additionally, they felt strongly that the devices themselves needed to be more realistic. In particular, they did not like the abstract illustration of the wheelchairs with “wheels [that] have no spokes” or that “the wheelchairs are not modern and the push handles scream dependency.” They also noted that the walker in Option 2 “seems to be missing back wheels.”

Regarding “non-disability diversity,” most felt that Option 1 was a better representation of the “different skin tones, hair color” of people with spina bifida, while Option 2 was perceived as less racially diverse. In particular, they criticized Option 2 for not including a Latinx character. They felt the final illustration could be improved by including additional Latinx as well as Asian characters. As one person stated, “Add my daughter… Asian.”

Participants commented on several aspects of the character’s “other physical appearance.” Many felt the bodies of the characters in Option 1 “accurately reflect kids with spina bifida,” although one participant disliked that they were all heavier. Similar to Round 1, they felt the body types in Option 2 were all “too skinny,” and not “realistic.” Including a wider variety of body types to the final illustration was recommended. Many participants resonated with the character with glasses in Option 1, with one stating “I’ve seen a lot of people with SB who wear them.” To improve the illustration, one person also requested including a non-binary figure. Finally, several respondents requested inclusion of a broader age range, such as “I wish it showed multiple ages” from “young toddler to older individuals.”

Participants had strong, mostly positive “emotional responses,” with many simply stating “representation” and “inclusion.” Several personally resonated with specific characters, commenting “the little boy standing without support is my son” and “the blond girl looks like me!” The mood, friendliness, health, and strength of the characters were important to participants. Most felt the characters in Option 1 were a better representation as it “depicts happy people with spina bifida, like my child is. It really bothers her that people with disabilities are often portrayed negatively in the media!” Another commented, “The boy waving looks really healthy, which represents many of us…the picture seems stronger.” In contrast, some commented that the characters in Option 2 looked “weak” and “ill.” However, some felt that some characters in both images did not appear friendly. They recommended the final characters be depicted as clearly happy, friendly, and healthy.

Overall, participants preferred the “design style” of Option 1 compared to Option 2. They felt the character’s eyes of Option 2 “looked odd” and the image “[lacked] detail,” whereas for Option 1 they felt the “eyes/faces are better.” Many suggested that adding more characters would improve the picture, both to improve the design of the image and to better reflect the diversity of people with spina bifida. “It’s hard to include everyone in one picture, but… Showing a crowd of people with varying abilities… to feel more inclusive, especially for those with SB viewing it (It’s more likely for people with disabilities to feel isolated when representation is limited).” Additionally, several requested that the characters be doing something or have “items like instruments, books, sports equipment, to show interests or personality.”

Participants had the option to add any additional comments at the end of the survey. Three participants commented on how this is needed for their children. As one stated, “[Sex ed] has gotten so much better in the past decade… but there is almost nothing out there talking about what puberty and sex ed could or should look like for disabled kids. I want there to be more to offer my daughter.”

The research team discussed further refinement to the illustration. It was decided that expanding the number of characters with a variety of ages, abilities, races, and body types was important. It was also critical to show more types of assistive devices and make them more realistic. The characters would be clearly happy, friendly, and holding or wearing something that demonstrated their interests or personality. The new illustration was developed and shared with an Advisory Board of adolescents with a physical disability and one of their parents, who approved the image (Figure 3). It was then shared with the Spina Bifida Association to post on their Instagram account.

Discussion

This work has culminated in the co-production of a user-centered illustration of a group of adolescents with physical disabilities to be used in medical education materials. Results of this study demonstrate the importance of seeking stakeholder feedback when developing an illustration representative of a specific population. Although the initial image was created with input from two physicians who regularly care for people with spina bifida and an artist with a physical disability, participants in this study shared critical feedback that informed key refinements for the final illustration. Specifically, participants strongly wanted their assistive devices accurately depicted. Additionally, they wanted to relate to the physical appearance of the characters, such as ethnicity and body type. It was important to respondents that the characters appear clearly happy, friendly, strong, and healthy. The design style was also important, which may be why participants in the survey overall preferred Option 1 despite feeling that Option 2 more accurately depicted what it looks like to have spina bifida. The enthusiasm for the images also reflected the scarcity of educational materials that include representative illustrations for people with disabilities. It is promising that adolescent-focused educational material using the illustrations co-developed with this work will more effectively teach adolescents with spina bifida about their sexual and reproductive health compared to existing non-disability focused curricula.

This study gave important insight to how participants view their own disability. The greatest proportion of comments for each image question focused on critiques for portraying the character’s physical disability more accurately. Spina bifida causes a range of physical disability, with many having no visible outward signs of a physical disability. While our hypothesis that it would be important to demonstrate a range of assistive devices was upheld, we did not anticipate it be just as important to include characters without any assistive device. This may reflect the unique and often underestimated experiences of people living with invisible physical disabilities, who often feel isolated due to not clearly fitting into society’s categories of “disabled” or “not disabled.”24, 25 This study suggests that people with invisible disabilities, similar to those with visible disabilities, also feel under-represented and are eager to see images reflective of their experience. Additionally, while participants preferred more abstract appearing characters (e.g., Option 1 instead of Option 2 in Round 1), they passionately felt their mobility aids should be realistically portrayed. This is similar to the illustrative style known as “ligne claire” which uses cartoonish characters but otherwise realistic details.26 In the final illustration, attention was paid to ensuring the features of the mobility aids were accurately portrayed while the characters themselves were cartoonish.

This work also lends insight to how participants feel they are perceived by society. The portrayal of people with physical disabilities in the media has been perceived as negative and reinforcing stereotypes such as that people with disabilities are asexual, incapable of being employed, or pitiable.27, 28 Several participants specifically commented on the importance of combatting such negative media by showing happy, healthy, and strong characters that more accurately represented their reality. Additionally, it was important that the characters be doing something reflective of their hobby or job to show both their personality and ability.

The results of this study also demonstrate the importance of obtaining qualitative feedback when developing an illustration. While the quantitative data is reported here, the team found it of limited usefulness when developing refinements. Indeed, critical refinements would have been missed if only quantitative questions were used. For example, although 75.5% of respondents felt Round 2 Option 1 looked “kind of like them or their child,” and 92.3% felt they kind of looked “kind of like other people [they knew] with spina bifida,” they made passionate comments about how much they disliked the wheelchairs. Left uncorrected, it would likely have impacted how they perceived any future educational materials. Additionally, the qualitative responses allowed unexpected new ideas for further improvement to be discovered, such as including more people with glasses and giving the characters hobbies.

The current lack of educational materials tailored to people with physical disabilities contributes to the pervasive disparities in health outcomes for this population, including those outcomes related to sexual and reproductive health.13-15, 19, 29-35 Culturally sensitive educational materials and interventions have proven more effective than standard care at addressing current health disparities and improving outcomes and self-management skills in minority populations.10-12 Specifically, user identification with the pictures in health educational materials has been proven to improve behavioral change intentions. 37 This is thought to be due to the homophily principle, which states people are more likely to be influenced by other people with whom they identify.36,37 This suggests that a sexual health educational curriculum with images and content tailored to adolescents with physical disabilities may improve both knowledge and health behavior, which could in turn improve long-term outcomes.

There are several limitations to this study. Only people who attended the Spina Bifida Association’s Clinical Care Conference and those who follow the Spina Bifida Association’s Instagram account were included in this study. Although the Spina Bifida Association is the only national spina bifida advocacy group, those who do not follow the Spina Bifida Association may differ from those who do in important ways. However, this was mitigated by the diversity of participants. Many respondents in the second survey were older than the intended target audience for the future educational materials. Nonetheless, based on the themes of feedback received, we anticipate that their feedback was valuable and relevant to this refinement process. It was feasible for participants to answer the survey more than once, thereby skewing the frequency of certain results. However, the purpose of this study was to try to incorporate all end-user feedback to modify a picture and not analyze prevalence or incidence. Additionally, incorporating end-user feedback into the design process requires creative liberties, some of which are difficult to articulate in a scientific paper. Finally, while the authors’ intention is to create materials initially targeted to adolescents with spina bifida and later expand them to adolescents with other causes of physical disabilities, this work has focused on the spina bifida population and may not be generalizable to adolescents with other physical disabilities.

Conclusion

This work demonstrates the importance of representation in illustrations and images for patient educational materials to this group of marginalized adolescents. Stakeholder feedback during the development of the illustrations allowed for the identification and inclusion of features future users prioritized. Specifically, we identified the importance of accurately depicting assistive devices, including characters with invisible disabilities, ensuring a diversity of people based on race and other physical features, and ensuring the characters were friendly, strong, and involved in jobs or activities. Next steps include developing the educational cartoon videos and corresponding handouts on sexual and reproductive health topics for adolescents with spina bifida and testing their acceptability and effectiveness compared to materials created for a general population.

Supplementary Material

Table 6.

Round 2 Coding of Responses to Open-Ended Survey Items “What do you LIKE about this picture?”, “What do you NOT LIKE about this picture?”, and “What would you CHANGE about this picture?”

| Comment Category | Option 1 Frequency | Option 2 Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| n = 125 | n = 106 | |

| Theme: Depiction of Disability | ||

| What do you LIKE about this picture? | ||

| Range of assistive devices | 28 | 34 |

| Inclusion of individuals without assistive devices | 26 | - |

| Realistic depiction of disability/mobility aids | 1 | - |

| What do you NOT LIKE about this picture? | ||

| Lack of individuals without assistive devices | 3 | 31 |

| Lack of people with just orthotics/braces | - | 5 |

| Lack of range of mobility aids | 12 | 1 |

| Walker not realistic | - | 4 |

| Wheelchair not realistic | 7 | 3 |

| What would you CHANGE about this picture? | ||

| Add someone who does not use mobility aids | 6 | 28 |

| Add someone with orthotics/braces only | 7 | 7 |

| Add more people with a range of mobilities | 6 | 4 |

| Add someone with a walker | 9 | - |

| Make wheelchairs more realistic | 4 | 3 |

| Take out the walker | - | 2 |

| Add someone with a walking stick | 1 | 1 |

| Add someone with skinny legs | 1 | 1 |

| Add someone with “pigeon toes” | 1 | 1 |

| Add an oxygen tank | 1 | 1 |

| Add someone with an adaptive shoe | - | 1 |

| Add someone with a gait trainer | 1 | - |

| Make the walker more realistic | - | 1 |

| Add someone with scoliosis | - | 1 |

| Add child with strong upper body | - | 1 |

| Add a service dog | 1 | - |

| Theme: Non-Disability Diversity | ||

| What do you NOT LIKE about this picture? | ||

| Lack of general diversity | 6 | 4 |

| Lack of body type diversity | 1 | 7 |

| Lack of ethnic diversity | 1 | 5 |

| Lack of diversity of ages | 2 | - |

| What would you CHANGE about this picture? | ||

| Add someone Asian | 6 | 5 |

| Add diversity in body types | 1 | 9 |

| Add someone Hispanic | - | 2 |

| Add general racial/ethinic diversity | 1 | 1 |

| Add more people | - | 1 |

| Theme: Other Physical Appearance | ||

| What do you NOT LIKE about this picture? | ||

| Characters look too old | 2 | - |

| Clothes/hair not trendy enough | 1 | - |

| Lack of character with glasses | - | 1 |

| What would you CHANGE about this picture? | ||

| Characters should be doing something | 5 | 2 |

| Make them look younger | 1 | - |

| Add someone who is non-binary | 1 | 1 |

| Make 2 characters a couple | 1 | - |

| Theme: Emotional Response | ||

| What do you LIKE about this picture? | ||

| Friendly appearance | 6 | 9 |

| Good representation | 6 | 5 |

| Look happy | 8 | - |

| Look normal/healthy | 5 | - |

| Looks like me/my child | 5 | - |

| I like it | - | 4 |

| I don’t like it | - | 4 |

| Shows unity | - | 2 |

| What do you NOT LIKE about this picture? | ||

| Characters look unwell or unhappy | 3 | 2 |

| What would you CHANGE about this picture? | ||

| Make them look happier/friendlier | 3 | 2 |

| Make them look strong/healthy | - | 1 |

| Make them stand closer together | 1 | - |

| Theme: Design Style | ||

| What do you LIKE about this picture? | ||

| Realistic | 6 | - |

| Character eyes | 4 | - |

| General design style | 4 | - |

| Colors | - | 3 |

| What do you NOT LIKE about this picture? | ||

| Character eyes | - | 23 |

| Character faces | 3 | 11 |

| General design style | 2 | 9 |

| Characters not doing anything | 1 | - |

| Colors | 1 | - |

| What would you CHANGE about this picture? | ||

| Change the eyes | 1 | 13 |

| Change the faces | - | 5 |

| Make the colors brighter/deeper | 1 | 4 |

| Add someone with glasses | - | 4 |

| Make more realistic | 2 | 1 |

| Add someone who is non-binary | 1 | 1 |

| Change the general style | 1 | 1 |

| Make hair/clothes more modern | 1 | - |

Contributor Information

Jennna Goldstein, University of Michigan School of Medicine.

Jennifer Latham Robinson, Limb Horizons (https://www.limbhorizons.com/).

Neela Nallamothu, University of Michigan.

Mieke Hart, University of Michigan.

Syndney V Ohl, Michigan State College of Human Medicine.

John S. Wiener, Deptartment of Surgery, Division of Urology, Duke University School of Medicine

Courtney S. Streur, Department of Urology, University of Michigan School of Medicine

Sources

- 1.Ilic N, Prescott A, Erolin C, Peter M. Representation in medical illustration: the impact of model bias in a dermatology pilot study. Journal of visual communication in medicine. Aug 1 2022:1–10. doi: 10.1080/17453054.2022.2086455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agic B, Fruitman H, Maharaj A, et al. Advancing Curriculum Development and Design in Health Professions Education: A Health Equity and Inclusion Framework for Education Programs. The Journal of continuing education in the health professions. Aug 9 2022;doi: 10.1097/ceh.0000000000000453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen JJ, Gabriel BA, Terrell C. The case for diversity in the health care workforce. Health affairs (Project Hope). Sep-Oct 2002;21(5):90–102. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marzolf BA, McKee MM, Okanlami OO, Zazove P. Call to Action: Eliminate Barriers Faced by Medical Students With Disabilities. Annals of family medicine. Jul-Aug 2022;20(4):376–378. doi: 10.1370/afm.2824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crites K, Johnson J, Scott N, Shanks A. Increasing Diversity in Residency Training Programs. Cureus. Jun 2022;14(6):e25962. doi: 10.7759/cureus.25962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Disability Impacts All of Us. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Disability and Health Promotion. Updated 9/16/2020. Accessed 8/31/2022, https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/infographic-disability-impacts-all.html

- 7.Wallington SF, Oppong B, Iddirisu M, Adams-Campbell LL. Developing a Mass Media Campaign to Promote Mammography Awareness in African American Women in the Nation's Capital. J Community Health. Aug 2018;43(4):633–638. doi: 10.1007/s10900-017-0461-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman AJ, Cosby R, Boyko S, Hatton-Bauer J, Turnbull G. Effective teaching strategies and methods of delivery for patient education: a systematic review and practice guideline recommendations. J Cancer Educ. Mar 2011;26(1):12–21. doi: 10.1007/s13187-010-0183-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moralez EA, Rao SP, Livaudais JC, Thompson B. Improving knowledge and screening for colorectal cancer among Hispanics: overcoming barriers through a PROMOTORA-led home-based educational intervention. J Cancer Educ. Jun 2012;27(3):533–9. doi: 10.1007/s13187-012-0357-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun AC, Tsoh JY, Saw A, Chan JL, Cheng JW. Effectiveness of a culturally tailored diabetes self-management program for Chinese Americans. Diabetes Educ. Sep-Oct 2012;38(5):685–94. doi: 10.1177/0145721712450922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim MT, Heitkemper EM, Hébert ET, et al. Redesigning culturally tailored intervention in the precision health era: Self-management science context. Nurs Outlook. Sep-Oct 2022;70(5):710–724. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2022.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim MT, Kim KB, Huh B, et al. The Effect of a Community-Based Self-Help Intervention: Korean Americans With Type 2 Diabetes. American journal of preventive medicine. Nov 2015;49(5):726–737. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.04.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson P, Kitchin R. Disability, space and sexuality: access to family planning services. Social science & medicine (1982). Oct 2000;51(8):1163–73. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00019-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McRee AL, Haydon AA, Halpern CT. Reproductive health of young adults with physical disabilities in the U.S. Preventive medicine. Dec 2010;51(6):502–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu JP, McKee MM, McKee KS, Meade MA, Plegue M, Sen A. Female sterilization is more common among women with physical and/or sensory disabilities than women without disabilities in the United States. Disabil Health J. Jul 2017;10(3):400–405. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2016.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mosher W, Hughes RB, Bloom T, Horton L, Mojtabai R, Alhusen JL. Contraceptive use by disability status: new national estimates from the National Survey of Family Growth. Contraception. Jun 2018;97(6):552–558. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2018.03.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rowen TS, Stein S, Tepper M. Sexual health care for people with physical disabilities. J Sex Med. Mar 2015;12(3):584–9. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drew JA, Short SE. Disability and Pap smear receipt among U.S. Women, 2000 and 2005. Perspectives on sexual and reproductive health. Dec 2010;42(4):258–66. doi: 10.1363/4225810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaplan C. Special issues in contraception: caring for women with disabilities. Journal of midwifery & women's health. Nov-Dec 2006;51(6):450–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2006.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alhusen JL, Bloom T, Anderson J, Hughes RB. Intimate partner violence, reproductive coercion, and unintended pregnancy in women with disabilities. Disability and health journal. Apr 2020;13(2):100849. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2019.100849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Casteel C, Martin SL, Smith JB, Gurka KK, Kupper LL. National study of physical and sexual assault among women with disabilities. Inj Prev. Apr 2008;14(2):87–90. doi: 10.1136/ip.2007.016451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG. Disability and Risk of Recent Sexual Violence in the United States. Am J Public Health. May 2016;106(5):928–33. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2015.303004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Linstow ME, Biering-Sørensen I, Liebach A, et al. Spina bifida and sexuality. Journal of rehabilitation medicine. Oct 2014;46(9):891–7. doi: 10.2340/16501977-1863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cortés MC, Hollis C, Amick BC 3rd, Katz JN. An invisible disability: Qualitative research on upper extremity disorders in a university community. Work. 2002;18(3):315–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stone SD. Reactions to invisible disability: the experiences of young women survivors of hemorrhagic stroke. Disability and rehabilitation. Mar 18 2005;27(6):293–304. doi: 10.1080/09638280400008990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wikipedia. Linge Claire. Accessed 10/7/2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ligne_claire

- 27.Black RS, Pretes L. Victims and Victors: Representation of Physical Disability on the Silver Screen. 2007;32(1):66–83. doi: 10.2511/rpsd.32.1.66 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang L, Haller B. Consuming Image: How Mass Media Impact the Identity of People with Disabilities. Communication Quarterly. 2013/July/01 2013;61(3):319–334. doi: 10.1080/01463373.2013.776988 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Streur CS, Schafer CL, Garcia VP, Quint EH, Sandberg DE, Wittmann DA. "If Everyone Else Is Having This Talk With Their Doctor, Why Am I Not Having This Talk With Mine?": The Experiences of Sexuality and Sexual Health Education of Young Women With Spina Bifida. J Sex Med. Jun 2019;16(6):853–859. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Decter RM, Furness PD, Nguyen TA, McGowan M, Laudermilch C, Telenko A. Reproductive understanding, sexual functioning and testosterone levels in men with spina bifida. The Journal of urology. Apr 1997;157(4):1466–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee NG, Andrews E, Rosoklija I, et al. The effect of spinal cord level on sexual function in the spina bifida population. Journal of pediatric urology. Jun 2015;11(3):142.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2015.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cromer BA, Enrile B, McCoy K, Gerhardstein MJ, Fitzpatrick M, Judis J. Knowledge, attitudes and behavior related to sexuality in adolescents with chronic disability. Developmental medicine and child neurology. Jul 1990;32(7):602–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Motta GL, Bujons A, Quiróz Y, Llorens E, Zancan M, Rosito TE. Sexuality of Female Spina Bifida Patients: Predictors of a Satisfactory Sexual Function. Revista brasileira de ginecologia e obstetricia : revista da Federacao Brasileira das Sociedades de Ginecologia e Obstetricia. Jun 2021;43(6):467–473. Sexualidade feminina em pacientes com espinha bífida: preditores de uma função sexual satisfatória. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1732464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iezzoni LI, Kurtz SG, Rao SR. Trends in Pap Testing Over Time for Women With and Without Chronic Disability. American journal of preventive medicine. Feb 2016;50(2):210–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.06.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sawyer SM, Roberts KV. Sexual and reproductive health in young people with spina bifida. Developmental medicine and child neurology. Oct 1999;41(10):671–5. doi: 10.1017/s0012162299001383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haynes D, Hughes KD, Okafor A. PEARL: A Guide for Developing Community-Engaging and Culturally-Sensitive Education Materials. J Immigr Minor Health. Oct 20 2022:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10903-022-01418-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buller MK, Bettinghaus EP, Fluharty L, et al. Improving health communication with photographic images that increase identification in three minority populations. Health Educ Res. Apr 1 2019;34(2):145–158. doi: 10.1093/her/cyy054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.