Abstract

Introduction

This is the first study aimed at objectively quantifying the benefit of virtual education using WhatsApp-based discussion groups.

Methods

A prospective, non-randomised interventional study was undertaken in the Department of General Surgery, at a tertiary care centre in Kolkata, India, with 200 undergraduate students over a period of 5 days each for 2 weeks, with the first week acting as a control arm. A WhatsApp group was created consisting of 197 eligible undergraduates, faculty members and the authors of this study. Each day, three questions were posted on this group. The second week involved an hour-long WhatsApp-based discussion between the participants and the faculty. Responses were recorded and compared for improvements between the two weeks. Participant feedback was collected and analysed.

Results

Statistically significant improvements were observed in the study group compared with the control group in rates of one in three, two in three and three in three correct responses (p=0.01649, 0.01146 and 0.00946, respectively). A total of 68 (51.92%) feedback respondents were satisfied with the programme. Convenience of use was the principal reason behind satisfaction in 79 respondents (60.31%), whereas 62 participants (47.33%) reported lack of hands-on training as a major drawback.

Conclusions

WhatsApp was found to be a satisfactory supplement to traditional medical teaching. It can be implemented to fill lapses in medical education, especially in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has caused great disruption to traditional teaching methods. Research is needed to assess the feasibility of incorporating it into the curriculum.

Keywords: Surgical education, WhatsApp, Undergraduate learning

Introduction

The creation and meteoric rise of instant messaging over the past decade has seen billions of people buy into, and indeed become dependent on, the idea of being connected to each other 24/7. Platforms such as WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, WeChat, etc see billions of users sharing tens of billions of messages, be it simple text messages, photos, documents or even videos.1 With a near universal use of smartphones, there has also been rapid growth in the use of such communication services in the field of medicine.2 In recent times, instant messaging platforms have become popular for exchange of informal academic correspondence among medical students, such as notes for tests or discussion of doubts.3,4

Existing studies with relatively small cohorts show that WhatsApp can be used to augment medical education by facilitating more convenient interaction between students and teachers, even outside the confines of a traditional classroom setting, which is the need of the hour due to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, these studies have relied mainly on feedback analysis as a measure of determining the effectiveness of this mode of teaching except one study from France that aimed at determining subjectively the benefit of WhatsApp-based teaching among anaesthesiology residents.5 This study was thus performed to objectively analyse the outcome of WhatsApp-based teaching of general surgery in the undergraduate (UG) setting following a definite protocol with a relatively large study population.

Methodology

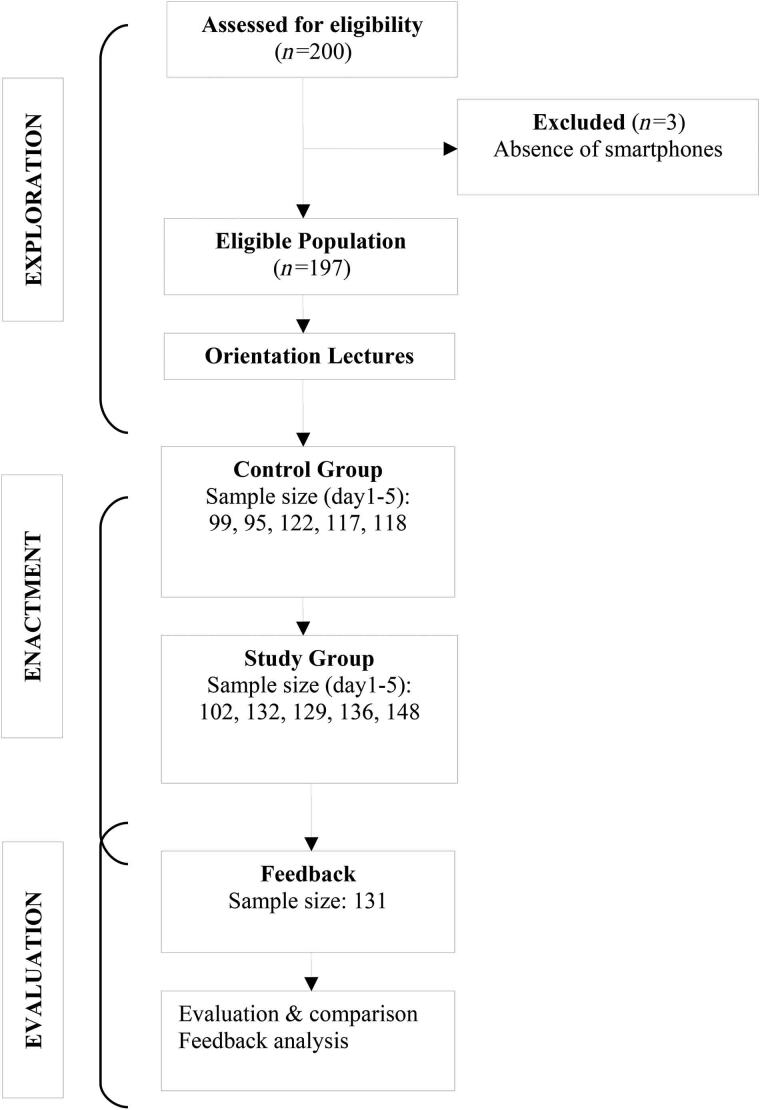

This prospective non-randomised interventional study was conducted over a 4-month period from 1 August 2019 to 30 November 2019 in a tertiary care centre in Kolkata, India. Our study was modelled on the ‘exploration–enactment–assessment integrated learning design framework’ (an instant messenger design model for medical education) proposed by Coleman and O’Connor in 2019 and was conducted in three stages: (1) exploration, (2) enactment and (3) evaluation.6 With proper ethical clearance, a batch of 200 students in the final year of the UG medical curriculum had scheduled lecture classes on ‘hernia’ and ‘shock’ over a period of 2 months. A total of 197 students from this batch were added in a WhatsApp group as shown in the CONSORT diagram along with faculty members from the Department of General Surgery and the authors of this study (Figure 1). Therefore, in the exploration phase the context of instant messenger (IM) learning was UG students with selected IM instructional strategy of primary educational with curriculum and voluntary participation after addressing social and cultural issues and allowing sharing of online multimedia messages on WhatsApp as the IM platform.

Figure 1 .

Stages of the study

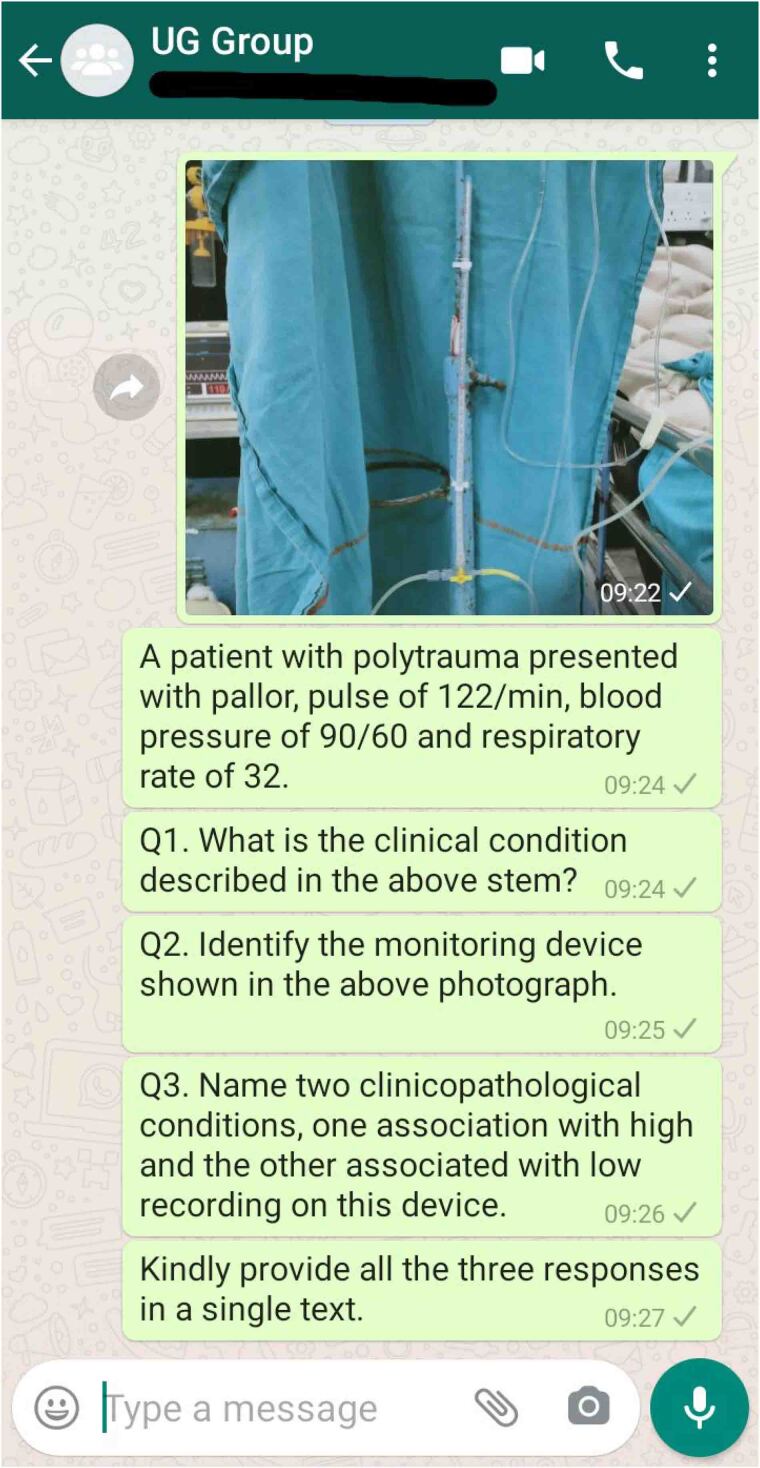

In the enactment stage, as per the selected IM instructional strategy 30 questions (3 per day) were put up in the group by faculty members based on the above-mentioned topics over a period of 10 days (Monday to Friday for two consecutive weeks) (Figure 2). In the first week, three questions were asked each day, responses recorded and the correct answers mentioned at the end of the day. However, no discussion about the questions was carried out and this set of responses acted as the control group for the study. In the second week the same process was repeated with the addition of a 1-h discussion on the questions asked by the faculty members along with addressing doubts and queries of individual students from 8.00 pm to 9.00 pm each day. In the enactment stage, feedback was collected with a preformed questionnaire in Google Forms format uploaded in the WhatsApp group, participation information was exported and learner assessment performed with Kirkpatrick’s training evaluation model. Compilation and analysis of the data was done using Microsoft Excel 2010 and subsequently MedCalc statistical software (version 19.2, www.medcalc.org). Categorical variables were described by their frequencies and compared using the chi-square test. All reported p values assume a level of significance of <0.05 and are two tailed.

Figure 2 .

Screenshot taken from the group discussion on WhatsApp showing the example of three questions from one day of the study

Results

Exploration

Out of 200 UG students attending the orientation lectures, 197 were recruited due to the lack of a smartphone with the remaining 3.

Enactment

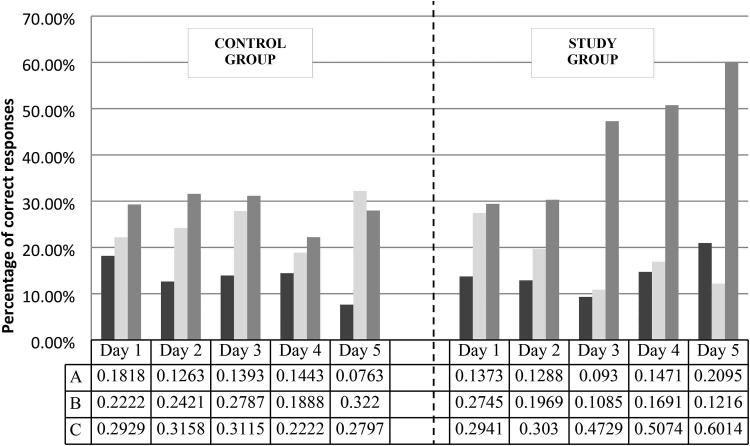

In the control arm of the study, the numbers of participants from Monday to Friday were 99 (50.25%), 95 (48.22%), 122 (61.93%), 117 (59.39%) and 118 (59.89%), respectively. The numbers of students with one out of three correct responses were 18 (18.18%), 12 (12.63%), 17 (13.93%), 17 (14.43%) and 9 (7.63%) from Monday to Friday, respectively, with a median of 17. Similarly, the numbers of students with two out of three and three out of three correct responses across the week were 22 (22.22%), 23 (24.21%), 34 (27.87%), 22 (18.88%) and 38 (32.2%); and 29 (29.29%), 30 (31.58%), 38 (31.15%), 26 (22.22%) and 33 (27.97%), respectively, with medians of 23 and 30, respectively (Figure 3). The trend in variation of one out of three and three out of three correct responses were not statistically significant, with p values of 0.14592 and 0.08164, respectively. However, this was statistically significant for the two out of three responses correct group (p=0.02752).

Figure 3 .

Percentage of correct responses recorded on days 1–5 in the control and study groups where A, B and C represent 1/3, 2/3 and 3/3 correct responses, respectively

In the study arm, the numbers of participants from Monday to Friday were 102 (51.78%), 132 (67.01%), 129 (65.48%), 136 (69.04%) and 148 (75.13%), respectively. Numbers of students with one out of three correct responses were 14 (13.73%), 17 (12.88%), 12 (9.3%), 20 (14.71%) and 31 (20.95%) (median value of 17); two out of three correct responses were 28 (27.45%), 26 (19.69%), 14 (10.85%), 23 (16.91%) and 18 (12.16%) (median value of 23); and all correct responses were 30 (29.41%), 40 (30.3%), 61 (47.29%), 69 (50.74%) and 89 (60.14%) (median value of 61), respectively, from Monday to Friday (Figure 3). Median participation of 59.39% in the control arm increased to 67.01% in the study arm; however, this increase was not statistically significant (p=0.49166). In the study arm, the trend in variation of two out of three and three out of three correct responses was statistically significant, with p values of 0.00566 and 0.00001, respectively. But the trend in one out of three correct responses was not statistically significant and the p value was 0.08828.

Evaluation

On comparison of the number of one out of three correct responses between the control and the study groups with the help of chi-square test (for more than two categories), a statistically significant improvement was noted in the study group postintervention (p=0.01649). On performing similar analyses on the two out of three and three out of three correct responses, statistical significance was noted with p values of 0.01146 and 0.00946, respectively.

The feedback questionnaire contained three single choice and three multiple choice questions. A total of 131 (66.49%) complete feedbacks were received. A majority of 76 (58.02%) participants were noted to spend more than 1 h on WhatsApp daily, followed by 47 (35.88%) and 8 (6.11%) spending 30–60 min and less than 30 min on WhatsApp, respectively. On a Likert Scale of 1 (extremely dissatisfied) to 5 (extremely satisfied), a majority of 68 (51.92%) participants were satisfied (score of 4) with the programme and a weighted average of 3.63 was achieved in this category. Convenience of participation was the major cause behind a higher level of satisfaction (79, 60.31%), whereas lack of hands-on training (62, 47.33%) was the major cause of dissatisfaction with the programme (Table 1). On a Likert scale of 1 (very poor) to 5 (very good), a majority of 63 (48.09%) of participants rated WhatsApp as a supplementary tool in surgical education with 4 (good); the weighted average was 3.59. Integration on hands-on training, a lecture format and better audiovisual aids were suggested by 58 (44.27%), 50 (38.17%) and 48 (36.64%) participants as the top three areas for improvement of the programme.

Table 1 .

Participant feedback analysis showing reasons for satisfaction, dissatisfaction and suggestions for improvement of the study

| Reasons for satisfaction | N | % | Reasons for dissatisfaction | N | % | Suggestions for improvement | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participation at own convenience | 79 | 60.3 | No hands-on training | 62 | 47.3 | Integration of hands-on training | 58 | 44.3 |

| Supplementation of previous knowledge | 45 | 34.4 | Difficulty of expression on WhatsApp | 50 | 38.2 | Better explanation or audiovisual aids | 48 | 36.6 |

| Audiovisual aids | 43 | 32.8 | Standard too high | 45 | 34.4 | No time restriction for interaction with faculty | 46 | 35.1 |

| Material available for review | 37 | 28.2 | Standard too low | 22 | 16.8 | Extra pressure and should not be made mandatory | 20 | 15.3 |

| More interaction with faculty members | 41 | 31.3 | Discussion not beneficial/adequate | 27 | 20.6 | Should be in lecture format | 50 | 38.2 |

| Tool for assessment of knowledge | 34 | 25.9 | Distraction on social media | 38 | 29 | |||

| Others | 20 | 15.3 | Others | 32 | 24.4 |

Discussion

In 1966, in an article published by the National Academies Press, Washington, DC, telemedicine has been defined as ‘the use of electronic information and communications technologies to provide and support health care when distance separates the participants’.7 From the use of telephones and radios for establishing communication between medical personnel to the advent of telesurgery, the frontiers of telemedicine have expanded dramatically.7 The COVID-19 pandemic has imposed an unprecedented challenge on every healthcare system worldwide, including a significant effect on medical education and training.8 This has lead to an increasing interest in the use of social-media-based delivery of medical education; WhatsApp with its 1 billion users is one of the most popular and powerful social media platforms that has been used extensively in improving healthcare services. Even though this study was conducted few months prior to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in India, the authors found this pilot study to have made them better equipped to deal with the online delivery of surgical education among UG students in the study institution during extensive periods of lockdown and social distancing.

Published literature giving examples of using various social media in medical education has gained impetus since the early twentieth century.9 In a short span of the last couple of years, studies have reported the use of WhatsApp in antenatal care to improve maternal and newborn health, for improving knowledge regarding type 2 diabetes mellitus and psoriasis, evaluation of haematuria via pictures sent through WhatsApp, communication in a paediatric burns unit, prevention of smoking relapse, and so on and so forth.10–15 It has been found to be especially beneficial in resource-limited situations, eg in improvement in rural healthcare systems.16 In the field of general surgery, various authors found the WhatsApp Messenger app to be a fast, economical and secure channel among surgeons and a promising tool for improvement in modern healthcare delivery systems.17–20 In a study entitled ‘WhatsApp in clinical practice: a literature review’ by Mars and Scott, 32 studies were reviewed, of which 12 were found to be from India and 14 were conducted in surgery-related disciplines.21 In the current study, a majority of 98.5% of the students had WhatsApp preinstalled in their smartphones, a finding similar to the meta-analysis conducted by Guraya in 2016, where 70–80% of the surveyed medical students were found to use social media on a daily basis but only 20% of them also used it for academic purposes.22

The only study prior to ours that was found to evaluate WhatsApp as an e-learning method among 62 anaesthesiology residents in France in a randomised prospective setting documented a statistically significant improvement in medical reasoning (self-assessed online by a script concordance test) but no difference in medical knowledge (assessed using multiple-choice questions) was seen between the control and study groups. A statistically higher level of satisfaction was seen in the group with WhatsApp based e-learning by an online questionnaire.5 Instead of randomisation, the same cohort of students were assessed in this study pre and postintervention, making it the first of its kind. This was done primarily as no form of blinding was possible among students in the same class at it might have lead to the feeling of being ‘left out’ among students in the control group and to minimise selection bias. With this study design, a statistically significant improvement in medical knowledge was assessed with multiple choice questions.

According to the feedback received, a majority of the UG students (94%) used WhatsApp for >30 min daily, whereas a majority of postgraduate students (90.91%) used it for >30 min daily. However, median participation rates were only moderate, with 59% in the control arm increasing to 67% in the study arm. The increase in participation rates was not statistically significant but could suggest higher interest in interactive forms of learning. A majority of 65% of participants were satisfied with the program, with convenience of participation (60%) being the main reason, as pointed out by other authors.5,23 Students who were dissatisfied felt so largely due to the lack of face-to-face interaction in this format. Congruent with the findings of Raiman et al,2 44% of the participants who provided feedback wanted hands-on clinical training along with the online format, indirectly pointing out the utility of the latter format being essentially of a supplementary nature. Distraction due to notifications of group activity being a reason behind dissatisfaction with blended learning has been suggested previously by other authors.24 Keeping this in mind, active efforts were made by the authors to maintain professionalism and confine discussions to strictly academic ones. However, total correspondence generated was higher in our study than that observed by other authors, probably because of the large sample size in our study.2,25 Distraction due to high volume of correspondence was also mentioned as a disadvantage of this format by 29% of our participants.

It is documented in available literature that instant messaging applications such as WhatsApp are well accepted in modern clinical practice.26–28 However, the role of WhatsApp or other social media in medical education has not yet been defined conclusively and is not free of criticism. According to the study conducted by Al Faris et al, WhatsApp was the most popular social media used by almost all the medical students included in the study; however, only a minority documented using it for academic purposes.29 In other studies, WhatsApp has been found to have no effect on academic performance.29,30 In their study, Vogelsang et al31 are of the opinion that internet-based media have a minor role to play in medical education, whereas Goyal et al25 have suggested that WhatsApp-based learning should capture as much screen time of students as possible. Moreover, the lack of hands-on clinical experience being cited as the major drawback points out even more distinctly the monumental role of the teacher–student interaction and conventional classroom and clinical teaching in the field of surgery.

The use of instant messaging platforms helps bridge the gap between students and teachers by enabling a livelier interaction as compared with didactic teaching methods. In the backdrop of prevailing lockdowns and social distancing norms, healthcare professionals are turning to novel methods of imparting medical education, and social media platforms such as WhatsApp with secure and accessible formats are gaining popularity. The significant effect of WhatsApp in imparting surgical education, assessed objectively in this study, coupled with 63% of the participants finding WhatsApp-based case discussion to be a good supplementation of surgical education provides an optimistic outlook towards its use in surgical teaching and evaluation.

References

- 1.Statista. WhatsApp: number of users 2013–2017. https://www.statista.com/statistics/260819/number-of-monthly-active-whatsapp-users/ (cited July, 2020).

- 2.Raiman L, Antbring R, Mahmood A. WhatsApp messenger as a tool to supplement medical education for medical students on clinical attachment. BMC Med Educ 2017; 17: 7. 10.1186/s12909-017-0855-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Browne G, O’Reilly D, Waters Cet al. Smart-phone and medical App use among Irish medical students: A survey of Use and attitudes. BMC Proc 2015; 9(Suppl 1): A26. 10.1186/1753-6561-9-S1-A26 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Chronicle of Higher Education. E-mail is for old people. http://www.chronicle.com/article/E-mail-is-for-Old-People/4169. (cited Nov 2019).

- 5.Clavier T, Ramen J, Dureuil Bet al. Use of the smartphone App WhatsApp as an E-learning method for medical residents: multicenter controlled randomized trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019; 7: e12825. 10.2196/12825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coleman E, O'Connor E. The role of WhatsApp in medical education; a scoping review and instructional design model. BMC Med Educ 2019; 19: 279. 10.1186/s12909-019-1706-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Field MJ, Institute of Medicine, eds. Telemedicine: A Guide to Assessing Telecommunications in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dedeilia A, Sotiropoulos MG, Hanrahan JGet al. Medical and surgical education challenges and innovations in the COVID-19 era: a systematic review. In Vivo 2020; 34(3 Suppl): 1603–1611. 10.21873/invivo.11950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheston CC, Flickinger TE, Chisolm MS. Social media use in medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med 2013; 88: 893–901. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828ffc23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel SJ, Subbiah S, Jones Ret al. Providing support to pregnant women and new mothers through moderated WhatsApp groups: a feasibility study. Mhealth 2018; 4: 14. 10.21037/mhealth.2018.04.05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turki A, Sulaiman B, Sara Aet al. Evaluation of a mobile social networking application for improving diabetes Type 2 knowledge: an intervention study using WhatsApp. J Comp Eff Res 2018; 7: 891–899. 10.2217/cer-2018-0028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazzuoccolo LD, Esposito MN, Luna PCet al. WhatsApp: A real-time tool to reduce the knowledge gap and share the best clinical practices in psoriasis. Telemed J E Health 2018; 25: 294–300. 10.1089/tmj.2018.0059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sener TE, Butticè S, Sahin Bet al. WhatsApp Use In The evaluation of hematuria. Int J Med Inform 2018; 111: 17–23. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2017.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martinez R, Rogers AD, Numanoglu A, Rode H. The value of WhatsApp communication in paediatric burn care. Burns 2018; 44: 947–955. 10.1016/j.burns.2017.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheung YTD, Chan CHH, Wang MPet al. Online social support for the prevention of smoking relapse: A content analysis of the WhatsApp and Facebook social groups. Telemed J E Health 2017; 23: 507–516. 10.1089/tmj.2016.0176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zawada ET Jr, Kapaska D, Herr Pet al. Prognostic outcomes after the initiation of an electronic telemedicine intensive care unit (eICU) in a rural health system. S D Med 2006; 59: 391–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Sahabi A, Sidhoum N, Assaf Net al. WhatsApp: improvement tool for surgical team communication. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2017; 70: e22. 10.1016/j.bjps.2017.05.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brewster CT, King IC. WhatsApp: improvement tool for surgical team communication. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2017; 70: 705–706. 10.1016/j.bjps.2016.11.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ewbank C, Groen RS, Kushner AL, Gupta S. WhatsApp: An essential m-health tool for global surgeons. Surgery 2017; 161: 1745–1746. 10.1016/j.surg.2017.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nardo B, Cannistrà M, Diaco Vet al. Optimizing patient surgical management using WhatsApp application in the Italian healthcare system. Telemed J E Health 2016; 22: 718–725. 10.1089/tmj.2015.0219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mars M, Scott RE. Whatsapp in clinical practice: A literature review. Stud Health Technol Inform 2016; 231: 82–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guraya SY. The usage of social networking sites by medical students for educational purposes: A meta-analysis and systematic review. N Am J Med Sci 2016; 8: 268–278. 10.4103/1947-2714.187131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oyewole BK, Animasahun VJ, Chapman HJ. A survey on the effectiveness of WhatsApp for teaching doctors preparing for a licensing exam. PLoS ONE 2020; 15: e0231148. 10.1371/journal.pone.0231148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smyth S, Houghton C, Cooney A, Casey D. Students’ experiences of blended learning across a range of postgraduate programmes. Nurse Educ Today 2012; 32: 464–468. 10.1016/j.nedt.2011.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goyal A, Tanveer N, Sharma P. WhatsApp for teaching pathology postgraduates: a pilot study. J Pathol Inform 2017; 8: 6. 10.4103/2153-3539.201111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giordano V, Koch H, Godoy-Santos Aet al. WhatsApp messenger as an adjunctive tool for telemedicine: an overview. Interact J Med Res 2017; 6: e11. 10.2196/ijmr.6214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arunagiri V, Anbalagan K. Communications through WhatsApp by medical professionals. Indian J Surg 2016; 78: 428. 10.1007/s12262-016-1541-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ganasegeran K, Renganathan P, Rashid A, Al-Dubai SA. The m-health revolution: exploring perceived benefits of WhatsApp use in clinical practice. Int J Med Inform 2017; 97: 145–151. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al Faris E, Irfan F, Ponnamperuma Get al. The pattern of social media use and its association with academic performance among medical students. Med Teach 2018; 40: S77–S82. 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1465536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alkhalaf AM, Tekian A, Park YS. The impact of WhatsApp use on academic achievement among Saudi medical students. Med Teach 2018; 40: S10–S14. 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1464652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vogelsang M, Rockenbauch K, Wrigge Het al. Medical education for ‘Generation Z’: everything online?! – An analysis of Internet-based media use by teachers in medicine. GMS J Med Educ 2018; 35: Doc21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]