Abstract

Introduction

Burnout is of growing concern within the surgical workforce, having been shown to result in reduced job satisfaction, decreased patient satisfaction and higher rates of medical errors. Determining the extent of burnout and identifying its risk factors within UK surgical practice is essential to ensure appropriate interventions can be implemented to improve mental wellbeing.

Materials

A systematic search of PubMed, Medline, Embase, PsychINFO and Cochrane databases was performed, following PRISMA guidelines. Studies published between January 2000 and October 2019 that reported prevalence data or risk factors on burnout for surgeons working within the UK and/or the Republic of Ireland were included.

Findings

Ten papers met the inclusion criteria. The overall prevalence of burnout amongst surgeons in the UK was 32.0% (IQR 28.9–41.0%), with surgical trainees having the highest prevalence (59.0%) of burnout documented for any subgroup. The most common risk factors identified for burnout were younger surgeon age and lower clinical grade. Being married or living with a partner was found to be protective.

Conclusions

Burnout is highly prevalent in UK surgical specialties, mostly amongst surgical trainees. Targeted pre-emptive interventions based upon relevant risk factors for burnout should be prioritised, at both individual and institutional levels.

Keywords: Burnout, Surgery, Trainee, Mental wellbeing

Introduction

Burnout has been described as a state of declining performance in individuals who have been exhausted by their professional life.1 It has become increasingly relevant over recent years, and can manifest through both physical or behavioural characteristics, including emotional exhaustion (a state defined by over-extension and loss of enthusiasm for work; EE), depersonalisation (unempathetic behaviour and impersonality towards patients; DP) or a lack of personal accomplishment (subjective assessment of personal competence; PA).2,3 Several theories for the development of burnout centre around an imbalance between the demands that affected individuals exert on themselves versus the mental and physical resources that they have available.4

Unfortunately, burnout remains a highly prevalent condition amongst medical professionals worldwide, with the surgical specialties being no exception.5–12 Previous work has shown that at least half of British surgeons have been adversely affected by burnout3 across all stages of training.13,14 Specific demands on surgeons include the physically taxing nature of daily work, persistent rota gaps and gruelling training pathways.15–17 Of equal concern is the impact burnout has at both a departmental and national level, being shown to result in reduced job satisfaction, professionalism and patient satisfaction, and even to cause higher rates of medical errors.18

The high stress levels often associated with surgical training appear to directly impact this apparent high level of burnout.19 In order for any potential interventions to be devised to tackle this problem, understanding the extent of the issue and any underlying mechanisms is imperative. Given the workforce retainment issues and decreasing morale seen within surgical spheres at present,20 an up-to-date review of the prevalence and known risk factors for burnout is essential.

As such, we undertook a systematic review of the current evidence on burnout within the surgical specialties in the UK and Ireland, to describe the prevalence of burnout, identify known risk factors and report any remedial interventions.

Methods

Inclusion criteria

A systematic review was undertaken, as per the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.21 The inclusion criteria comprised studies that reported prevalence for burnout or identified risk factors for burnout in surgeons working within the UK and/or the Republic of Ireland since 2000. Studies were excluded if they did not present a quantifiable measure of burnout or did not include UK or Irish-specific data; books, editorials or review articles were also excluded, as were those not published in the English language.

Study selection

A literature search was undertaken using the PubMed, Medline, Embase, PsychINFO and Cochrane databases; the Open Grey database was also searched for any relevant unpublished literature. Searches included all articles published up to 25 October 2019, with any duplicates subsequently removed (search terms can be found in Supplementary Materials).

Studies were selected for inclusion within the systematic review initially via the abstracts being assessed for suitability by two reviewers independently (BB and AA), with any differences resolved by consensus. Articles of potential interest were then reviewed in full and those selected meeting all criteria were included in the study.

Data analysis

All prevalence values were presented, with median and interquartile ranges (IQR) calculated where appropriate. The prevalence values for the separate components of burnout (EE, DP, PA) were also reported where available.

The definition of burnout used was that reported in each individual study and was recorded separately for each included study. Some of the larger US-based studies use a definition of burnout as high EE or high DP levels only,22 however this definition is not useable unless this data has been collected and recorded from the beginning by individual studies. Historically, EE has been considered the main component of burnout although this, along with isolated use of PA, has been suggested to give incomplete results.23

The quality of the included studies and risk of bias was assessed using the Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS tool), with each paper given a score out of 20 based on its fulfilment of the specified criteria24 (Table 1).

Table 1 .

Studies included within the systematic review

| Paper | Published year | n | Specialty | Grade | AXIS score (/20) | Burnout measurement tool | Overall reported prevalence | Identified risk factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robinson25 | 2019 | 100 | NS | Trainees | 16 | MBI | 59.0 | Younger surgeon Female gender Lower training grade Single or no children Married or living with partner (protective) |

| Khan26 | 2018 | 108 | NS | Consultants | 18 | MBI | NS | NS |

| Vijendran14 | 2018 | 121 | ENT | Senior Trainees, Associate Specialists, and Consultants | 16 | MBI | 28.9 | NS |

| Hayes27 | 2018 | 243 | NS | Trainees and Consultants | 14 | MBI | 32.0 | NS |

| Walker28 | 2016 | 102 | ENT | CST, HST, Consultant | 17 | OBI | NS | Lower levels of grit |

| O’Kelly3 | 2016 | 575 | Urology | Consultants, Non-Consultants | 14 | MBI | 28.9 | Younger surgeon Female gender Position of responsibility Higher training grade |

| Upton29 | 2012 | 313 | General Surgery, Maxillofacial, ENT, T&O, Plastics, Urology, Cardiothoracic, Neurosurgery, Paediatrics | Senior Trainees and Consultants | 14 | MBI-GS | NS | Lower training grade Mood state profile |

| Sharma12 | 2008 | 486 | Colorectal, Vascular | Consultants | 16 | MBI | 32.0 | Younger surgeon Lack of communication or management training Married or living with partner (protective) |

| Catt30 | 2005 | 27 | Surgical Oncology | NS | 18 | MBI | NS | NS |

| Taylor31 | 2005 | 280 | Surgical Oncology | Consultants | 17 | MBI | 41.0 | NS |

MBI, Maslach Burnout Inventory; NS, not stated; OBI, Oldenburg Burnout Inventory

Findings

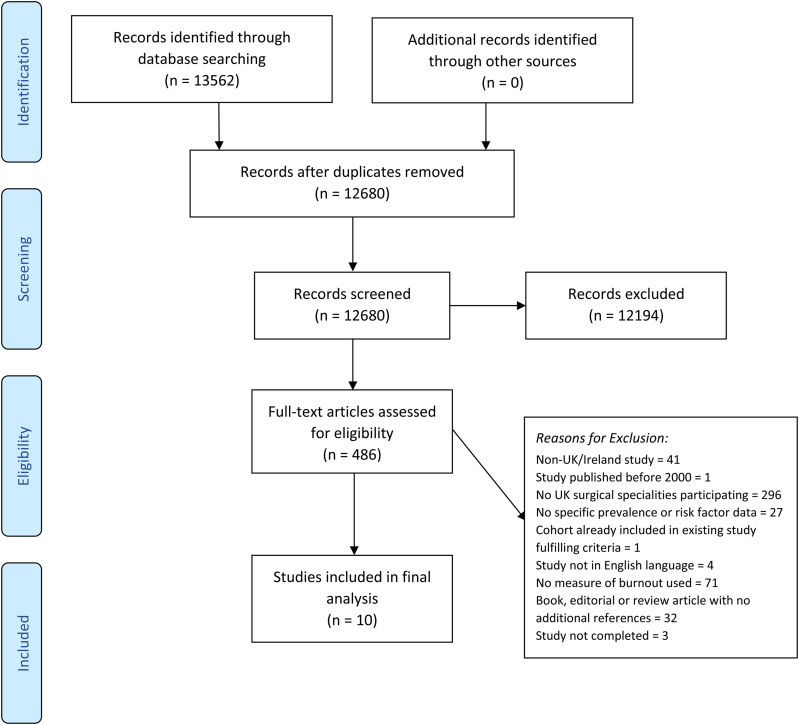

Ten papers fulfilled the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). The median number of participants in each study was 182 (IQR 102–313) and the most popular method of assessing burnout was the MBI (Maslach Burnout Inventory), employed by nine studies3,12,14,25–27,29–31 (Table 1). All surgical specialties, as defined by the Royal College of Surgeons of England,32 were covered in varying degrees across the included studies.

Figure 1 .

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart

One paper did include general physicians with an interest in otolaryngology, however 97% of its reported sample population were pure otolaryngology surgeons,14 and as such was included by author consensus. One paper was excluded33 as its sample population was derived from a larger study that had already been included.12

All studies used self-reporting questionnaires for data collection and all were cross-sectional in nature. Definitions of burnout varied between the included studies, with the prevailing definitions used comprising high levels of emotional exhaustion (EE) combined with either high depersonalisation (DP) or low levels of personal accomplishment (PA).3,14,27

Prevalence of burnout

The overall median prevalence of burnout in the UK and Ireland was 32.0% (IQR 28.9–41.0%)3,12,14,25,27,31 (Table 1). In the included studies, urologists3 and otolaryngology surgeons14 demonstrated the lowest overall prevalence of burnout (28.9%), while surgical oncology was the specialty with the highest reported prevalence (41.0%). A study of surgical trainees (of varying specialty and grade)25 reported the highest burnout prevalence overall of any paper at 59.0%, compared to the average of 41.0% (IQR 36.5–47.4%)3,31 for consultant surgeons.3,31

Focusing on the separate components of burnout, 32.4% (IQR 28.6–41.0%)3,12,25,26,30,31 of respondents demonstrated aspects of emotional exhaustion (EE), with the highest level reported in consultant surgeons (of varying specialty)26 (Table 2). The median prevalence of depersonalisation (DP) was 27.5% (IQR 24.1–34.5%),3,12,25,26,30 with the highest level being reported by surgical trainees (of varying specialties)25 (Table 3). Low levels of personal accomplishment (PA) had a median prevalence of 32.0% (IQR 29.4–37.2%),3,12,25,30 with the highest prevalence reported in urologists3 (Table 4).

Table 2 .

Studies included within the systematic review reporting emotional exhaustion (EE)

| Paper | Year | Region | n | Specialty | Grade | EE prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robinson25 | 2019 | Wales | 100 | NS | Junior and Senior Trainees | 33.0 |

| Khan26 | 2018 | UK | 108 | NS | Consultants | 43.5 |

| O’Kelly3 | 2016 | UK and Ireland | 575 | Urology | Consultants | 28.6 |

| Sharma12 | 2008 | UK | 486 | Colorectal, Vascular | Consultants | 31.7 |

| Catt30 | 2005 | UK | 27 | Surgical Oncology | NS | 22.0 |

| Taylor31 | 2005 | UK | 280 | Surgical Oncology | Consultants | 41.0 |

NS, not stated

Table 3 .

Studies included within the systematic review reporting depersonalisation (DP)

| Paper | Year | Region | n | Specialty | Grade | DP prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robinson25 | 2019 | Wales | 100 | NS | Junior and Senior Trainees | 39.0 |

| Khan26 | 2018 | UK | 108 | NS | Consultants | 27.5 |

| O’Kelly3 | 2016 | UK, Ireland | 575 | Urology | Consultants | 26.9 |

| Sharma12 | 2008 | UK | 486 | Colorectal, Vascular | Consultants | 21.2 |

| Catt30 | 2005 | UK | 27 | Surgical Oncology | NS | 30.0 |

NS, not stated

Table 4 .

Studies included within the systematic review reporting personal accomplishment (PA)

| Paper | Year | Region | n | Specialty | Grade | PA prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robinson25 | 2019 | Wales | 100 | NS | Junior and Senior Trainees | 34.0 |

| O’Kelly3 | 2016 | UK and Ireland | 575 | Urology | Consultants | 40.3 |

| Sharma12 | 2008 | UK | 486 | Colorectal, Vascular | Consultants | 28.8 |

| Catt30 | 2005 | UK | 27 | Surgical Oncology | NS | 30.0 |

NS, not stated

The recognition of EE as the main component of burnout and the definitions used by larger US-based studies were considered to identify whether this altered the overall prevalence of burnout. Recalculation of burnout prevalence using a definition where high EE was required, and in combination with a second component where available, resulted in the addition of two further papers26,30 and prevented the inclusion of isolated PA values. This revised version gave a similar overall prevalence value of 30.3% (IQR 25.5–36.5%).

Risk factors

The most commonly identified risk factor for burnout (or its components) was the age of the surgeon, with three studies demonstrating a higher burnout prevalence in younger surgeons3,12,25 (Table 1). An inverse relationship between the surgeon’s level of training and their risk of burnout was identified in two studies.25,29 One study did show an increased prevalence of burnout amongst consultants, but this was most pronounced for those in leadership roles.3 Detailed comparison of trends in degree of trainee seniority between different specialties was not possible due to limited availability of data.

Other risk factors for burnout identified from the included studies included female gender,3,25 inadequate training in communications and management skills,12 decreased job satisfaction,12 not having any children25 and a higher mood state (as defined by a Profile of Mood States (POMS) rating scale).29,34 Being married or living with a partner were found to be protective factors against burnout.12,25

Those who had positive coping mechanisms available were shown to have a lower prevalence of burnout; practices such as talking things over with family, social interaction with friends, or increasing levels of sport and recreation were reported to be effective coping mechanisms to reduce the impact of burnout.12 A higher risk of burnout was associated with changing food consumption (eating more or less), increased alcohol consumption and not discussing personal issues with others.12

Discussion

The World Health Organization recently revised their definition of burnout, now framing it as the derivation of an occupational problem, rather than purely a medical one.35 This systematic review demonstrates that approximately one in three UK surgeons suffer from burnout, which threatens the sustainability of the current surgical workforce in the UK. The wide variety of risk factors that we identified must be used to develop new strategies to address this, at both an organisational and national level, to support the surgical workforce against this growing problem.

Impacts on the workforce

Burnout is broadly high among doctors on a global scale, although rates often vary by country, medical specialty and practice setting.36 Our work has demonstrated a high prevalence of burnout within the surgical specialties in the UK; of note, the highest levels were reported by surgical trainees, with three out of every five demonstrating evidence of burnout.

A recent report released by the British Medical Association stated that the scale of burnout among junior doctors was “deeply concerning”.37 Newly qualified doctors have been shown to demonstrate emotional exhaustion only six months into their clinical careers,38 with no improvement over time in the job,39 alongside recent high-profile cases of junior doctor burnout in the media.40,41 These widespread findings suggest a picture of national concern, rather than just a case of individual plight, with broader institutional and cultural causation.

Such high prevalence of burnout across the surgical workforce in the UK should be seen as a significant issue for future workforce planning. Our data also reveals high levels of burnout among the consultant workforce in the UK and Ireland; indeed, one study concluded that early retirement in UK surgeons was more likely in those who had suffered from burnout.12 The recent NHS pensions crisis demonstrates the fragility in the bond that clinicians have to their jobs and the willingness that many have about leaving the profession if the stressors become too great.42 As the workforce depletes, the pressures and strains on those that remain will increase, resulting in higher levels of burnout and subsequent resignations in a vicious cycle.

Therefore, as a matter of urgency, interventions to address burnout and the mental health needs of clinicians in the UK should be developed and implemented, to mitigate further workforce degradation.

Developing interventions

Previous reports have shown the destructive coping mechanisms some clinicians use to deal with burnout.12,33 A limited number of services do currently exist to support surgeons in the UK with such concerns,43 but these services often require individuals to self-recognise their own symptoms of burnout, and the proportion of those seeking help and taking time off work is often lower than the proportion formally reporting burnout itself.3

The risk factors identified in this systematic review could be used to redesign the current support structure available to surgeons and trainees alike. Pre-emptive identification of high-risk individuals for burnout would allow for an early intervention and management strategy, at both local and national levels. Younger surgeon age and lower surgical grade were shown to be significant risk factors for developing burnout,25,29 therefore effective utilisation of and support to trainee-led groups, such as the Association of Surgeons in Training, in both a mentorship and educational capacity, could be one such way to address this workforce crisis.

Moreover, previous work has identified proven mechanisms that have helped UK surgeons to manage burnout.12,33 Education to prevent negative coping mechanisms, such as worsening food habits or increasing alcohol consumption, has some benefit at an individual level, however it is through changing workplace cultures, both departmentally and nationally by openly discussing these issues, that will be most effective.29 For any form of transformation within the NHS to occur, a cultural shift is required to tackle the factors that cause and sustain burnout.36 Offering mentoring to doctors at higher risk, such as those junior in their careers or undertaking clinical leadership roles, would provide a supportive organisational culture that may mitigate such risks.36

As with any study of this nature, the variability reported in the prevalence of burnout is probably due to the lack of standardisation in the definitions of burnout. However, using a broader definition of burnout, we demonstrated equivocal prevalence levels of burnout from the literature. There is also a theoretical risk of response bias with such data collection, however cross-sectional studies remain the mainstay of data collection in this area. In addition, only four of the included studies explicitly stated that collected data was anonymous, which we appreciate may prevent surgeons from accurately reporting their responses through potential fear of stigmatisation.

Conclusions

Burnout is a highly prevalent phenomenon in UK surgical specialties, affecting all grades and specialities. The highest prevalence was seen among surgical trainees and we identified numerous risk factors in developing burnout. The risk of burnout will probably increase due to the recent COVID-19 pandemic, with increased demands placed on all doctors working in the NHS from the change in rota patterns, redeployment to alien specialties and lack of contact due to government-led social restrictions.44 Although hospitals have made interventions to reduce stress at a local level, these are rare and further work is required to determine how surgeons could be trained to better self-recognise symptoms of burnout. Targeted interventions to address burnout at both the individual and institutional levels should be prioritised to prevent the damaging effects of burnout on the NHS, its staff and patient care.

Declarations of interest

MB is funded by the National Institute for Health Research.

References

- 1.Freudenberger HJ. Staff burn-out. J Soc Issues 1974; 30: 159–165. 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1974.tb00706.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav 1981; 2: 99–113. 10.1002/job.4030020205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Kelly F, Manecksha RP, Quinlan DMet al. Rates of self-reported “burnout” and causative factors amongst urologists in Ireland and the UK: a comparative cross-sectional study. BJU Int 2016; 117: 363–372. 10.1111/bju.13218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guditus CW. Staff Burnout: Job Stress in the Human Services Cary Cherniss Beverly Hills, California: Sage Publications, 1980, 199 pp. J Teach Educ 1981; 32: 55–56. 10.1177/002248718103200418 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aldrees T, Badri M, Islam T, Alqahtani K. Burnout among otolaryngology residents in Saudi Arabia: a multicenter study. J Surg Educ 2015; 72: 844–848. 10.1016/j.jsurg.2015.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng H, Shao H, Zhou Y. Burnout among Chinese adult reconstructive surgeons: incidence, risk factors, and relationship with intraoperative irritability. J Arthroplasty 2018; 33: 1253–1257. 10.1016/j.arth.2017.10.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arora M, Diwan AD, Harris IA. Prevalence and factors of burnout among Australian orthopaedic trainees: a cross-sectional study. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2014; 22: 374–377. 10.1177/230949901402200322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jesse MT, Abouljoud M, Eshelman Aet al. Professional interpersonal dynamics and burnout in European transplant surgeons. Clin Transplant 2017; 31: e12928. 10.1111/ctr.12928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel R, Huggard P, van Toledo A. Occupational stress and burnout among surgeons in Fiji. Front Public Health 2017; 5: 41. 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps GJet al. Burnout and career satisfaction among American surgeons. Ann Surg 2009; 250: 463–470. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181ac4dfd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elmore LC, Jeffe DB, Jin Let al. National survey of burnout among US general surgery residents. J Am Coll Surg 2016; 223: 440–451. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma A, Sharp DM, Walker LG, Monson JRT. Stress and burnout in colorectal and vascular surgical consultants working in the UK National Health Service. Psychooncology 2008; 17: 570–576. 10.1002/pon.1269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halliday L, Walker A, Vig Set al. The relationship between grit and burnout: how do surgical trainees compare to other doctors? Int J Surg 2016; 36(Suppl 1): S36. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.517 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vijendren A, Yung M, Shiralkar U. Are ENT surgeons in the UK at risk of stress, psychological morbidities and burnout? A national questionnaire survey. Surgeon 2018; 16: 12–19. 10.1016/j.surge.2016.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalager T, Søgaard K, Boyle Eet al. Surgery is physically demanding and associated with multisite musculoskeletal pain: a cross-sectional study. J Surg Res 2019; 240: 30–39. 10.1016/j.jss.2019.02.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ashmore DL. Strategic thinking to improve surgical training in the United Kingdom. Cureus 2019; 11: e4683. 10.7759/cureus.4683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dean E. Burnout and surgeons. Bull R Coll Surg Engl 2019; 101: 134–136. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med 2002; 136: 358–367. 10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lebares CC, Guvva E V, Ascher NLet al. Burnout and stress among US surgery residents: psychological distress and resilience. J Am Coll Surg 2018; 226: 80–90. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Royal College of Surgeons of England. Half of surgeons concerned by low workplace morale – Royal College of Surgeons. https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/news-and-events/media-centre/press-releases/member-survery-low-morale/ (cited June 2020)

- 21.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009; 339: b2535. 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky Cet al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2017. Mayo Clin Proc 2019; 94: 1681–1694. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med 2018; 283: 516–529. 10.1111/joim.12752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, Dean RS. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open 2016; 6: e011458. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robinson DBT, James OP, Hopkins Let al. Stress and burnout in training; requiem for the surgical dream. J Surg Educ 2019; 77: e1–8. 10.1016/j.jsurg.2019.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khan A, Teoh KR, Islam S, Hassard Jet al. Psychosocial work characteristics, burnout, psychological morbidity symptoms and early retirement intentions: a cross-sectional study of NHS consultants in the UK. BMJ Open 2018; 8: e018720. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hayes B, Wash G, Prihodova L. National survey of wellbeing of hospital doctors in Ireland. Occup Environ Med 2018; 75(Suppl 2): A6–A7. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walker A, Hines J, Brecknell Jet al. Survival of the grittiest? Consultant surgeons are significantly grittier than their junior trainees. J Surg Educ 2016; 73: 730–734. 10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Upton D, Mason V, Doran Bet al. The experience of burnout across different surgical specialties in the United Kingdom: a cross-sectional survey. Surgery 2012; 151: 493–501. 10.1016/j.surg.2011.09.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Catt S, Fallowfield L, Jenkins Vet al. The informational roles and psychological health of members of 10 oncology multidisciplinary teams in the UK. Br J Cancer 2005; 93: 1092–1097. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor C, Graham J, Potts HWWet al. Changes in mental health of UK hospital consultants since the mid-1990s. Lancet 2005; 366: 742–744. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67178-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Royal College of Surgeons of England. Surgical Specialties. https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/careers-in-surgery/trainees/foundation-and-core-trainees/surgical-specialties/ (cited September 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharma A, Sharp DM, Walker LG, Monson JRT. Stress and burnout among colorectal surgeons and colorectal nurse specialists working in the National Health Service. Colorectal Dis 2008; 10: 397–406. 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01338.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McNair D. Profile of Mood States. San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Service; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 35.WHO | Burn-Out an “Occupational Phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases. WHO. World Health Organization, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lemaire JB, Wallace JE. Burnout among doctors. BMJ 2017; 358: j3360. 10.1136/bmj.j3360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.BMA. Number of Junior Doctors Suffering Burnout is ‘Deeply Concerning’. BMA. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nason GJ, Liddy S, Murphy T, Doherty EM. A cross-sectional observation of burnout in a sample of Irish junior doctors. Ir J Med Sci 2013; 182: 595–599. 10.1007/s11845-013-0933-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Connor P, Lydon S, O’Dea Aet al. A longitudinal and multicentre study of burnout and error in Irish junior doctors. Postgrad Med J 2017; 93: 660–664. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2016-134626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.ITV News. What’s Life Like as a Junior Doctor and What do Current Trainees Wish They Had Known When they Started? https://www.itv.com/news/2019-08-07/what-s-life-like-as-a-junior-doctor-and-what-do-current-trainees-wish-they-has-known-when-they-started/ (cited September 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Independent. Junior Doctor Burnout Rising with one in Four Struggling with Workload, NHS Training Survey Reveals. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/health/junior-doctor-burnout-patient-safety-strike-jeremy-hunt-a8992641.html (cited September 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goldstone AR, Bailey D. NHS pensions crisis. BMJ 2019; 366: l4952. 10.1136/bmj.l4952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Royal College of Surgeons of England. Confidential Support and Advice Service for Surgeons (CSAS). https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/careers-in-surgery/csas/ (cited June 2019).

- 44.Kadhum M, Farrell S, Hussain R, Molodynski A. Mental wellbeing and burnout in surgical trainees: implications for the post-COVID-19 era. Br J Surg 2020; 107: e264–e264. 10.1002/bjs.11726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]