Abstract

Giant celiac artery aneurysm is a rare entity. We describe a case of a 45-year-old male with chronic kidney disease who presented with abdominal pain for the past 6 months. CT showed a celiac artery aneurysm of size 6×6.2cm involving the common hepatic artery and compressing the portal vein posteriorly. During the procedure the supra celiac aorta was exposed, and the neck of the aneurysm was identified. After taking control of branches of the celiac and common hepatic arteries, the neck of the aneurysm was clamped and divided. In view of diminished flow in the hepatic arteries aorto hepatic bypass was done using PTFE graft from supra celiac aorta to right hepatic artery; as there was retrograde flow from the left hepatic artery it was ligated. Post operatively the patient's liver functions were normal, and he was followed up by Doppler sonography which detected good flow in the hepatic artery distal to anastomosis. Celiac artery aneurysms are rare, and management options vary from the endovascular to surgery; regardless of the approach used, revascularisation is needed if there is no adequate collateral flow.

Keywords: Celiac artery aneurysm, Giant celiac artery aneurysm, Aorto hepatic bypass

Introduction

Celiac artery aneurysm is a rare variety of visceral artery aneurysm with high risk of rupture resulting in high mortality (13–50%).1 These aneurysms require early identification and prompt management in order to reduce this associated mortality.2 We present a case of giant celiac artery aneurysm.

Case report

A 45-year-old male had complaints of pain in the right upper abdomen for the past 6 months. He had known hypertension for the past 8 years and chronic kidney disease for the past 3 years. He was evaluated to identify the cause of chronic kidney disease but no obvious cause was identified. His biochemical and haematological parameters were normal except for haemoglobin which was 7.7mg/dl possibly due to chronic kidney disease, blood urea 74 and creatinine 3.4. Ultrasonography showed a hetero echoic lesion in the epigastric region of size 6.2×6.1cm likely arising from the celiac artery. CT angiography showed a celiac artery aneurysm of size 6×6.2cm involving the common hepatic artery, splenic and left gastric artery (Figure 1) and compressing the portal vein posteriorly (Figure 2). In view of the large size of the aneurysm endovascular therapy was not considered in this patient. He underwent laparotomy with midline incision, and the supra celiac aorta was exposed by opening the lesser omentum and by sharply dissecting the diaphragmatic crura. Once the supra celiac aorta was exposed the origin of the celiac artery was identified, and the infra renal aorta was also exposed and we took control over it. By dissecting in the porta region the common hepatic artery was identified and we took control over it, and the splenic artery was identified over the superior border of the pancreas. The celiac artery aneurysm was exposed, as were the branches to the left gastric, hepatic, and splenic arteries (Figure 3). After achieving control over these vessels and aorta, the neck of the aneurysm was identified and clamped using a curved clamp. Splenic artery, hepatic artery and left gastric artery were ligated and divided (Figure 4). The aneurysm was compressing the portal vein posteriorly and was adherent to it, so aneurysmectomy was not done. A side-biting clamp was placed on the aorta and end-to-side aorto hepatic bypass was done using PTFE graft from supra celiac aorta to right hepatic artery. Revascularisation was done in view of diminished retrograde hepatic artery flow from the gastroduodenal artery. As there was retrograde flow from the left hepatic artery it was ligated. There was no clinical and biochemical evidence of infection. The PTFE graft was used for reconstruction (Figure 5). Gross and microscopic evaluation of the surgical specimen confirmed that it was an atheromatous celiac artery aneurysm. Postoperatively the patient's liver functions were within normal limits and he was followed up by Doppler ultra sonography which detected good flow in the hepatic artery distal to anastomosis. His postoperative course was uneventful. Since his surgery one and a half years ago, he has remained asymptomatic and stable, with no evidence of expansion of the abdominal aneurysm on CT.

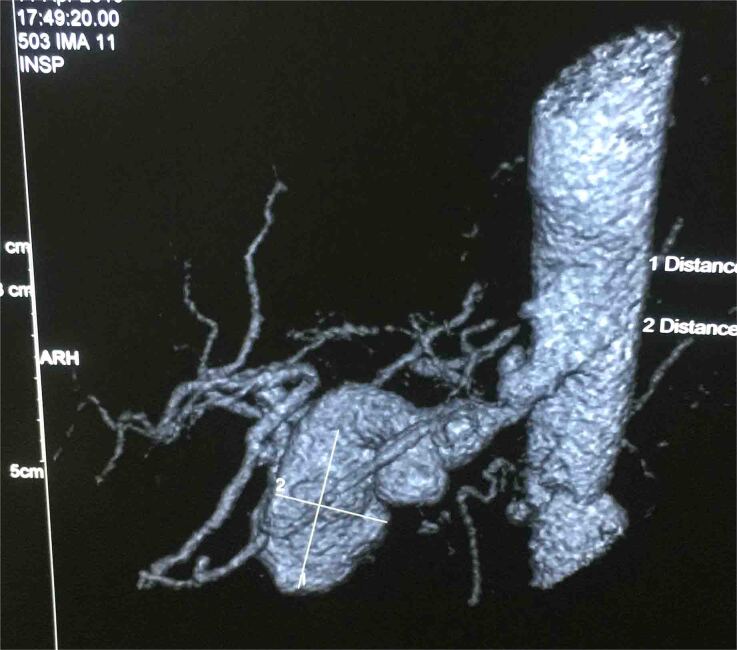

Figure 1 .

Celiac artery aneurysm of size 6×6.2cm involving the common hepatic artery, splenic and left gastric artery

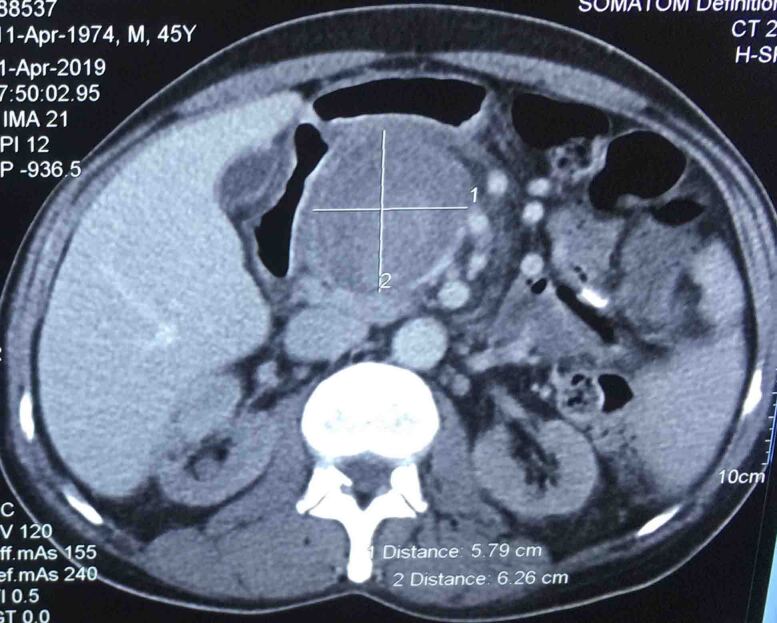

Figure 2 .

Giant celiac artery aneurysm compressing the portal vein posteriorly

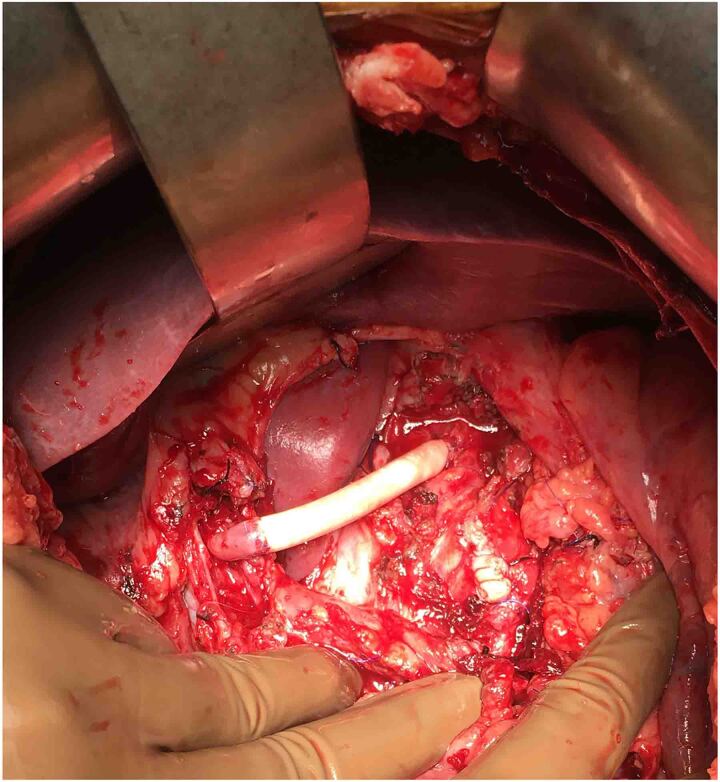

Figure 3 .

Aorto-hepatic bypass using PTFE graft from supra celiac aorta to right hepatic artery, left hepatic artery was ligated

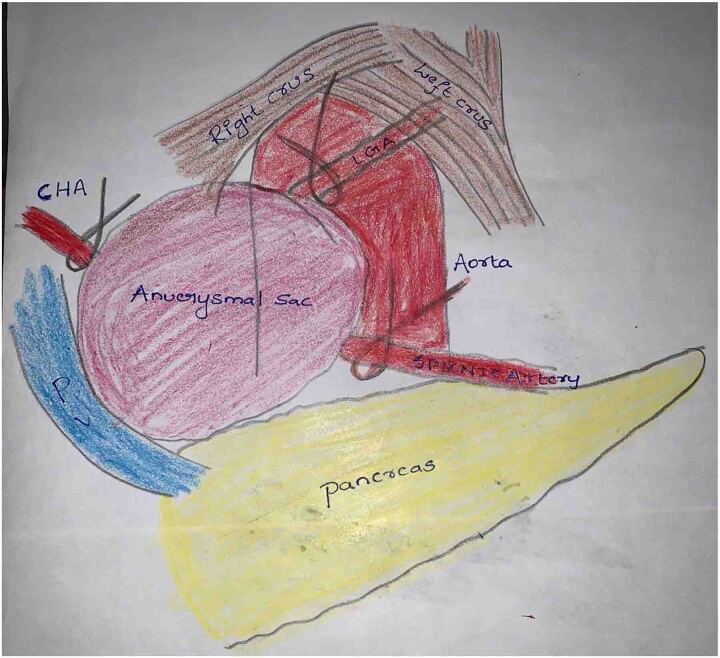

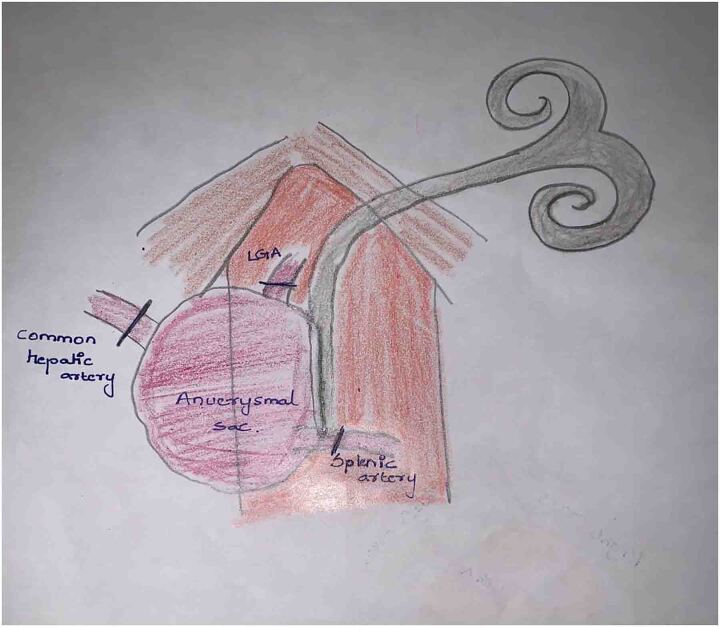

Figure 4 .

Dissection around diaphragmatic crura exposing the aneurysm sac and left gastric artery (LGA), dissection around the porta and pancreas exposed common hepatic artery (CHA) and splenic artery

Figure 5 .

After taking control of CHA, LGA and splenic artery these were ligated and side-biting clamp was applied across the aorta

Discussion

Visceral artery aneurysms are very uncommon with a reported incidence of 0.1–2%.3 Rupture of visceral artery aneurysms is associated with higher morbidity and mortality. Management depends on size, symptoms and associated comorbidities. Indications for intervention include rupture, symptomatic aneurysms, presence of a pseudoaneurysm or mycotic aneurysm, celiac axis or superior mesenteric artery aneurysms >2.5cm, renal artery aneurysms >2.5cm or >2.0cm in association with hypertension in young patients, and splenic aneurysms >2.5cm in diameter in women of childbearing age or 3.0cm in other groups.3 Intervention can be either surgical or endovascular; the endovascular approach is the preferred modality and surgery is reserved only for those cases where an endovascular approach is not feasible. The optimal approach depends on anatomy, risk factors, and underlying pathophysiologic mechanism. Giant celiac artery aneurysms are different from other visceral artery aneurysms in the sense that they are difficult to manage by both surgical and endovascular approach.

Celiac artery aneurysms account for 4–5% of visceral artery aneurysms and these are a rare entity.4,5 Mean age at presentation is 53 years with male preponderance. Most of these aneurysms are asymptotic; if symptomatic they present with mild upper abdominal pain, in our case the patient presented with painful abdomen.1 Most of these aneurysms are detected incidentally when radiological investigations like ultrasonography or CT are performed for other pathologies. CT angiography is the investigation of choice, with modern technology offering accurate imaging and 3D reconstruction of vascular anatomy that helps in detecting these aneurysms, and more importantly helps in planning the management of these aneurysms.6 In cases where CT cannot be done MR angiography is as good as CT. Digital subtraction angiography can be used both for diagnostic and therapeutic use (stent graft/coil embolisation).3,7 Identification of these aneurysms is important as the rupture of these aneurysms is associated with a mortality of up to 40%. Risk of rupture depends on the size of the aneurysm ranging from 5–60% (size <2cm (<5%) and size >3.2cm (50–70%);8 up to 9–18% of these aneurysms are found in association with abdominal aortic aneurysms and with splanchnic artery aneurysms in 50% of cases.9 Calcification of celiac aneurysms was seen in 20% of the patients and these are mostly curvilinear in nature. Whether these calcifications lead to increased risk of rupture is not known.1

Due to high mortality with rupture these patients require intervention; indications for intervention include symptomatic patients and increase in size of the aneurysm during follow-up.4 Intervention can be either radiological or surgical; usually surgical management is the standard of care but there are many reports where these aneurysms are successfully managed by endo-vascular techniques. These techniques vary from coil embolisation with NBCA, stent graft alone or stent graft with coil embolisation of the hepatic artery (Table 1). These endovascular techniques can be used in high-risk patients.8,11 Endovascular approaches are associated with high risk of distal embolisation if adequate coil packing is not done.10 The first successful surgery for celiac artery aneurysm was done by Shumacker in 1958;16 since then a variety of techniques have been successfully applied for the celiac artery aneurysms which include aneurysmorrhaphy, aneurysmectomy alone or in combination with aortoceliac anastomosis, hepatic–celiac anastomosis, hepatic/splenic–celiac inter-position graft, aortoceliac bypass and aorto hepatic bypass using a saphenous vein or prosthetic graft.1,4

Table 1 .

Various modalities used in management of celiac artery aneurysms

| Author | No of cases | Mean Size | Procedure performed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graham et al1 | 108 | 2.6cm |

|

| William M. Stone11 | 18 | 2.4cm |

|

| Ankur J. Shukla3 | 9 | 3.4cm | Endovascular intervention Open surgical technique |

| G. Lipari12 | 3 | – |

|

| Ichiro Matsukura13 | 2 | 1.8cm | Excision of the celiac artery and end-to-end anastomosis |

| Michael McMullan4 | 1 | 3cm | Saphenous vein bypass graft with anastomosis to splenic and hepatic arteries |

| Akira Aki7 | 1 | 5cm | NBCA with coil embolisation |

| Obteene Azimi-Ghomi14 | 1 | 1.4cm | Excision of sac+patch repair |

| Gregory Pattakos2 | 1 | 2.2cm | Saphenous vein bypass graft with anastomosis to splenic and hepatic arteries |

| Tetsuro Uchida15 | 1 | 3.5cm | PAS-Port system |

| Giampaolo Carrafiello16 | 1 | 2.5cm | Combined endovascular repair (stent+coil embolisation) |

| Christopher Twine6 | 1 | 5cm | Celiac axis ligation+revascularisation of hepatic, splenic (saphenous vein) and left gastric artery (celiac to left gastric) |

| Our case | 1 | 6.2cm | Ligation of the celiac axis+revascularisation of hepatic artery by aorto hepatic bypass graft |

Reconstruction is not always necessary if the flow to the hepatic arteries is maintained through the gastroduodenal artery. In case of absent or diminished flow in the hepatic arteries reconstruction is needed.6 In a review by Stone et al11 eight out of nine patients underwent revascularisation and one patient did not required any revascularisation in view of adequate collateralisation. In a review by Graham et al 35% did not require revascularisation, and 45% of the patients revascularisation in the contemporary era.1 In our index case the patient underwent ligation of celiac artery, splenic artery, left gastric and common hepatic artery. Aneurysmectomy was not done in our case as it was adherent and compressing the portal vein.

Conclusion

Celiac artery aneurysms are rare, and management options vary from the endovascular to surgery; regardless of the approach used revascularisation is needed if there is no adequate collateral flow.

References

- 1.Graham LM, Stanley JC, Whitehouse WMet al. Celiac artery aneurysms: historic (1745–1949) versus contemporary (1950–1984) differences in etiology and clinical importance. J Vasc Surg 1985; 2: 757–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arteries CH. Resection of celiac artery aneurysm with bypass grafting to the splenic and common hepatic arteries. Tex Heart Inst J 2017; 44: 77–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shukla AJ, Eid R, Fish Let al. Contemporary outcomes of intact and ruptured visceral artery aneurysms. J Vasc Surg 2015; 61: 1442–1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Connell JM, Han DC. Celiac artery aneurysms: a case report and review of the literature. Am Surg 2006; 72: 746–749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takeuchi N, Soneda J, Naito Het al. Successfully-treated asymptomatic celiac artery aneurysm: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2017; 33: 115–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Twine C, Wood A, Williams I. Surgical repair of a coeliac artery aneurysm. J Vasc Surg 2013; 57: 848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aki A, Ueda T, Koizumi Jet al. Mycotic celiac artery aneurysm following infective endocarditis: successful treatment using N-butyl cyanoacrylate with embolisation coils. Ann Vasc Dis 2012; 5: 208–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Røkke O, Søndenaa K, Amundsen Set al. The diagnosis and management of splanchnic artery aneurysms. Scand J Gastroenterol 1996; 31: 737–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pulli R, Dorigo W, Troisi Net al. Surgical treatment of visceral artery aneurysms: a 25-year experience. J Vasc Surg 2008; 48: 334–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiao N, Mansukhani NA, Resnick SA. et al. Giant celiac artery aneurysm. J Vasc Surg Cases Innov Tech 2019; 5: 447–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stone WM, Abbas MA, Gloviczki Pet al. Celiac arterial aneurysms. Arch Surg 2002; 137: 670–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lipari G, Cappellari TF, Giovannini Fet al. Treatment of an aneurysm of the celiac artery arising from a celiomesenteric trunk. Report of a case. Int J Surg Case Rep 2015; 8: 45–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsukura I, Iwai T, Inoue Y. Celiac artery aneurysm: report of two surgical cases. Surg Today 1999; 29: 948–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azimi-Ghomi O, Khan K, Ulloa K. Celiac artery aneurysm diagnosis and repair in the postpartum female. J Surg Case Reports 2017; 2017: 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uchida T, Hamasaki A, Kuroda Yet al. Surgical repair of a celiac artery aneurysm using a sutureless proximal anastomosis device. J Vasc Surg Cases Innov Tech 2017; 3: 221–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carrafiello G, Rivolta N, Annoni Met al. Endovascular repair of a celiac trunk aneurysm with a new multilayer stent. J Vasc Surg 2011; 54: 1148–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]