Abstract

Ulceration of the oral cavity is common and a frequent reason for referral to secondary and tertiary centres. Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-related mucocutaneous ulceration, however, is a rare cause of oral ulceration that has been described only recently. Histologically these lesions resemble lymphomas; however, their management and prognosis differ significantly. We present a case of EBV-induced oral ulceration and discuss the diagnosis and management of and available literature for the condition, which was treated successfully through conservative measures alone.

Keywords: Oral pathology, Lymphoma, Oral medicine, Maxillofacial surgery

Background

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), a member of the family Herpesviridae, is an infection that is prevalent in most demographic groups globally. It causes a wide spectrum of both systemic and local diseases, which can have a significant impact on health and quality of life.

Although primary infection by EBV is well documented, there appears to be little existing literature relating to the reactivation of the virus and its subsequent clinical presentations in relation to the immunosuppressed patient. Once reactivated, the virus has a range of presentations both intra- and extra-orally and hence is likely to be detected by clinicians from a wide variety of specialist teams on examination.

EBV-associated mucocutaneous ulceration is a relatively new phenomenon with classification of the condition only recently being added to the World Health Organisation (WHO) database in 2017. In this paper, we present a case of EBV infection that clinically appeared as malignant disease but on appropriate investigation proved to be benign pathology.

Case history

A 44-year-old Caucasian female was referred to the maxillofacial surgery team for investigation of new-onset ulceration in the oral cavity including on the alveolar mucosa and floor of the mouth.

The patient had a complex medical history and was under the care of multiple teams in the hospital. Of particular note was that the patient had been diagnosed six years ago with autoimmune hepatitis following a liver biopsy. She had been treated successfully with steroids and azathioprine for the last six years.

Upon examination of the patient, multiple ulcers were seen in the oral cavity including the floor of the mouth as well as the maxillary alveolar mucosa both buccally and palatally. Although most of the ulcers looked fairly innocuous, the maxillary ulceration (Figure 1) appeared to be necrotic with grey sloughing evident overlying the lesions. Some induration was also felt on palpation. Clinically the ulcers ranged in size from 5 to 15mm with no history of a relapsing–remitting pattern. This was suggestive of malignancy on initial examination. At this point, the differential diagnoses included a high-grade lymphoma, a squamous cell carcinoma and underlying HIV infection, which presents with ulcers that clinically appear similar intraorally. A biopsy of the lesion on the upper right maxillary alveolar mucosa was taken, which indicated a lymphoproliferative process that could not exclude lymphoma. The patient was referred to the haematology team for further investigation.

Figure 1 .

Ulceration on maxillary alveolar mucosa

A subsequent positron emission tomography (PET) scan requested by the haematology team showed no other lesions attributable to a high-grade lymphoma anywhere in the body. The sole lesion seen on the PET scan was confined entirely to the maxillary alveolus (Figure 1). Blood tests for hepatitis B and C and for HIV were carried out, which returned negative results. Hepatitis B and C infection has long been associated with the development of haematopoietic malignancies, especially non-Hodgkin lymphoma;1 therefore, antibody testing was completed to ensure this was not an underlying factor for development of lymphoma. HIV testing was carried out because of its association with lymphoma2 and potential to cause intra-oral ulceration.

A second biopsy was requested from the maxillofacial team, on which EBV serology and PCR was carried out. This sample tested positive for EBV DNA. It was concluded that this was an EBV-driven lymphoproliferative process in a patient who was immunosuppressed.

Histopathology

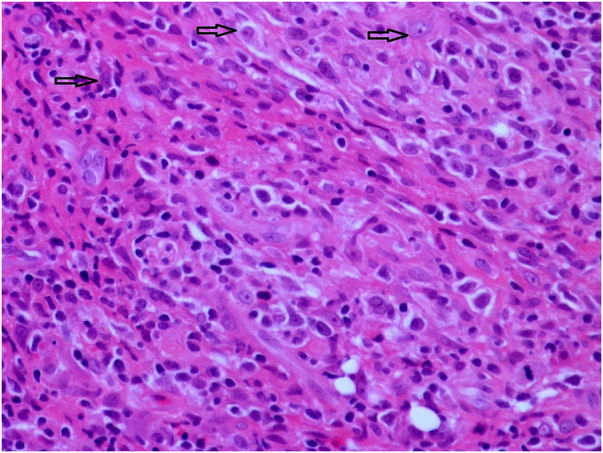

The biopsy sample showed ulcerated mucosa. There was a polymorphous infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes and a small number of plasma cells, and large atypical cells could be seen infiltrating smaller vessels (Figure 2). These cells tested positive for B-cell markers (CD 20, CD 79, A MUM 1 and PAX 8) and showed positive nuclear staining for EBV by in situ hybridisation (Figure 3).

Figure 2 .

H&E staining at 40× magnification shows large atypical cells with pleomorphic nuclei and small nucleoli

Figure 3 .

Epstein–Barr virus staining by in situ hybridisation (ISH) shows positive nuclear staining in atypical cells

Discussion

EBV infection is highly prevalent and is estimated to affect over 90% of the world’s population.3 Its major route of transmission is through oral secretions. During primary infection, it preferentially binds to B-lymphocytes and once established, will remain latent in an individual’s B-cells for life.4 Subsequent infection is prevented by cell-mediated immunity; however, immunosuppression allows the proliferation of EBV-infected cells.5 Immunosuppressed patients are therefore at an increased risk for EBV-associated lymphoproliferative disorders (EBV-LPD). Immunosuppression can occur owing to a multitude of reasons. Iatrogenic immunosuppression is a known phenomenon due to drugs such as methotrexate and azathioprine. Primary immunosuppression due to immunodeficiency syndromes (such as hypogammaglobulinaemia and T-cell deficiency) and also HIV infection is also well documented. Elderly non-immunocompetent individuals are also at risk of EBV-LPD because of age-related deterioration of the immune system (immunosenescence).6

For many years EBV has been implicated in the development of several malignancies both haematogenous (lymphoma) and epithelial (nasopharyngeal carcinoma). Oral manifestations of EBV-related ulceration remain relatively rare. EBV-positive mucocutaneous ulceration (EBVMCU) is a recently described clinicopathological entity first recognised in the 2017 WHO classification.7 It typically presents as a solitary well-circumscribed mucosal or cutaneous ulcer in the head and neck region. Tissue obtained for histological examination typically reveals a polymorphous infiltrate of large atypical B-cells and Reed–Sternberg-like cells.8

Nearly all reported cases of EBVMCU have a self-limiting course and tend to resolve spontaneously with reduction or withdrawal of immunosuppressive agents, without progression to disseminated disease. More resistant cases, especially in the elderly, may require therapeutic intervention. One such agent is rituximab, which achieves excellent results.9

This case highlighted the need for further immunohistochemistry in patients who present with suspicious lesions in a background of immunosuppression. Once EBV association was identified, the patient was managed by withdrawal of her immunosuppressant (azathioprine) with maintenance on steroids. She also received a 4-week course of rituximab. This resulted in complete resolution of the ulcers over a 4-month period, both clinically and on repeat PET scanning. Despite the withdrawal of her immunosuppressant, her autoimmune hepatitis remained quiescent.

It is important to recognise that EBVMCU is an indolent form of EBV-LPD requiring a different management strategy. Therefore, testing for EBV DNA is recommended in immunosuppressed and immunocompromised patients who present with suspicious lesions in the oral cavity that do not correlate to other symptoms that the patient may be experiencing. In these patients conservative management through reduction of immunosuppression is advised.

References

- 1.Anderson LA, Pfeiffer R, Warren JLet al. Hematopoietic malignancies associated with viral and alcoholic hepatitis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2008; 17: 3069–3075. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noy A. HIV lymphoma and Burkitts lymphoma. Cancer J 2020; 26: 260–268. 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tzellos S, Farrell PJ. Epstein-barr virus sequence variation-biology and disease. Pathogens 2012; 1: 156–174. 10.3390/pathogens1020156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young LS, Rickinson AB. Epstein-Barr virus: 40 years on. Nat Rev Cancer 2004; 4: 757–768. 10.1038/nrc1452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Au J, Said J, Sepahdari A, St John M. Head and neck epstein-barr virus mucocutaneous ulcer: case report and literature review. Laryngoscope 2016; 126: 2500–2504. 10.1002/lary.26009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daroontum T, Kohno K, Inaguma Yet al. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma arising in patient with a history of EBV-positive mucocutaneous ulcer and EBV-positive nodal polymorphous B-lymphoproliferative disorder. Pathol Int 2019; 69: 37–41. 10.1111/pin.12738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaulard P, Swerdlow SH, Harris NLet al. EBV-positive mucocutaneous ulcer. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Revised 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2016; pp 307–308. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dojcinov S, Venkataraman G, Raffeld Met al. EBV positive mucocutaneous ulcer – A study of 26 cases associated with various sources of immunosuppression. Am J Surg Pathol 2010; 34: 405–417. 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181cf8622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dojcinov SD, Fend F, Quintanilla-Martinez L. EBV-Positive Lymphoproliferations of B- T- and NK-cell derivation in non-immunocompromised hosts. Pathogens 2018; 7: 28. 10.3390/pathogens7010028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]