Abstract

Introduction

Sarcomas of the head and neck are neoplasms arising from the embryonic mesenchyme. They are rare and heterogeneous in nature and are associated with significant morbidity and mortality. This study evaluates patients referred to the Oxford Sarcoma Service, a tertiary referral centre.

Methods

Patients discussed over a three-year period were included. Medical records were analysed using the electronic patient record database. Data were acquired on a range of domains, including: demographics, histopathology, treatment modality, recurrence, mortality, survival, etc.

Results

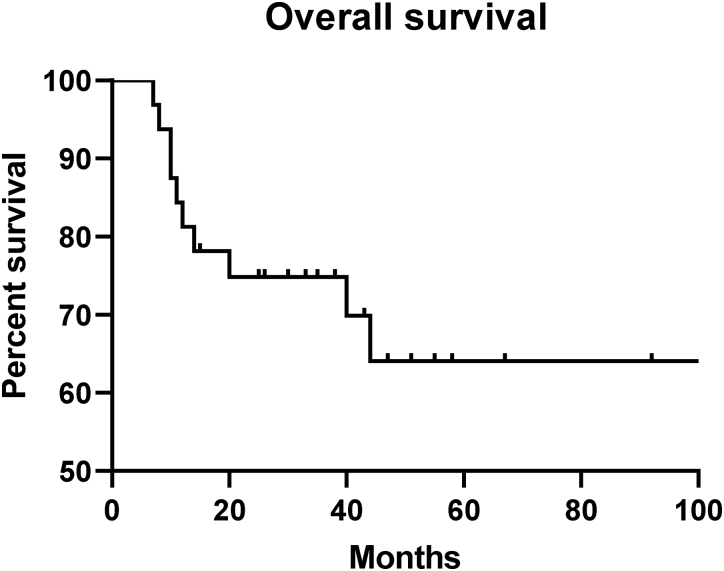

Thirty-two eligible patients, 21 male and 11 female, were identified with a mean age of 58 years; 26 out of 32 patients had high-grade sarcomas. The commonest histological subtype was chondrosarcoma (8/32). Twenty-two underwent planned multidisciplinary team surgical resection after biopsy and staging: negative margins were noted in 9, with close and involved margins in 5 and 8, respectively. Local recurrence was noted in 13 and 6 had metastatic disease out of the 32 eligible patients. Mortality was noted in 10 out of 32 patients. Mean survival was 69.5 months. Five-year overall survival was 64%. Surgery demonstrated statistically significant improvement in survival (p=0.0095). There were no significant differences in survival, recurrence or marginal status between methods of adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy.

Conclusion

Outcomes of head and neck sarcomas are inferior compared with other types of sarcoma. The nature of the complex surrounding anatomy presents unique challenges in surgical management. This in turn affects rates of local recurrence and prognosis. Therefore, it is critical that they are managed in tertiary, specialist centres with a multidisciplinary approach.

Keywords: Sarcoma, Head and neck, Surgery

Introduction

Sarcomas are heterogeneous, malignant tumours of mesenchymal origin. They are relatively uncommon with annual incidence estimated to be 5 per 100,000.1,2 Sarcomas are extremely diverse and can arise from soft tissue, including muscle, fat, vascular tissue, neural tissue and cartilage as well as from bone. Despite the variability that they exhibit, sarcomas share some similarities, such as embryological origin, initial presentation, principles of treatment, prognosis and outcome.3,4

Sarcomas of the head and neck (H&N) account for 5–10% of all sarcomas.5 They comprise a small proportion of H&N tumours overall, and this is estimated be 1%.6 The mainstay of treatment is en bloc surgical resection with negative margins combined with adjuvant and/or neoadjuvant therapies. However, when compared with sarcomas of the extremities, trunk or retroperitoneum, outcomes in the H&N group tend to be inferior.7 The surgical approach is inherently challenging as a result of the complex local anatomy with the presence of structures essential to both form and function reducing the ability to perform complete en bloc resection with negative margins, thereby influencing local recurrence rates and overall survival.8,9

Thus, optimal service delivery at tertiary referral centres is essential in order to manage the complex oncology associated with H&N sarcomas. The Oxford Sarcoma Service is one of five centres across the United Kingdom that is approved for the management of both primary bone and soft tissue sarcomas. Weekly, centralised, multidisciplinary team (MDT) meetings are held at the Nuffield Orthopaedic Centre where a diverse range of specialists discuss relevant cases of all sarcoma types. This study aims to evaluate H&N sarcomas managed by the Oxford Sarcoma Service.

Methods

Data were acquired from the local, electronic database. All H&N patients discussed in MDT meetings over a three-year period from 2016 to 2018 were included. This also compromised patients who may have been diagnosed prior to 2016 but were re-discussed in the MDT setting for a variety of reasons. The only conditions for eligibility in this study were definitively diagnosed sarcomas anatomically superior to the clavicle. Out of 49 H&N patients discussed, 32 met the inclusion criteria.

Data were collected on patient demographics (age at diagnosis, sex); histological subtype; soft tissue or bone; anatomical location; grade at diagnosis (high or low); treatment modality (surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy); marginal status (clear, involved, marginal); recurrence; metastases; and mean survival.

For statistical analysis all data were collated in a central database. All data were normality tested using a Shapiro–Wilk test. No data were transformed. In the event of a non-normal distribution, non-parametric methods were utilised. Data were grouped by marginal status, histological grade and treatment modality. For comparisons of continuous variables, non-paired t-test or ANOVA were used. For comparisons of dichotomous variables, Fisher’s exact test was used. Survival analysis estimates were generated using the Kaplan–Meier method followed by Log-rank integration. Overall survival was classified as the time from diagnosis to mortality of any cause in months (with appropriate censoring of those patients who had not yet reached the relevant follow-up periods). Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05. All analyses were completed on GraphPad Prism 8.

Results

Demographic data of the 32 eligible patients were obtained (Table 1). There were 21 male and 11 female patients. The mean age at diagnosis was 58 years, with an age range of 16–88 years.

Table 1 .

Demographic data

| Age (years) | Sex | Location | Histological subtype | Grade | Treatment modality | Marginal status | Recurrence | Metastases | Mortality | Survival (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 81 | M | Scalp | UPS | High | S | Clear | + | − | − | 51 |

| 55 | F | Orbit | Ewing’s sarcoma | High | S, R, C | Clear | − | − | − | 55 |

| 56 | F | Skull Base | Alveolar soft part sarcoma | Low | S, C | Clear | − | − | − | 67 |

| 16 | M | Mandible | Osteosarcoma | High | S, R | Clear | + | − | − | 479 |

| 28 | M | Skull Base | Chordoma | High | S, R | Clear | − | − | − | 47 |

| 65 | M | Neck | Leiomyosarcoma | High | C | N/A | − | − | + | 20 |

| 33 | M | Throat | Kaposi’s sarcoma | High | C | N/A | − | − | − | 38 |

| 69 | M | Mandible | Osteosarcoma | High | S, R, C | Clear | − | + | + | 7 |

| 84 | M | Scalp | UPS | High | S | Marginal | − | − | − | 43 |

| 47 | F | Maxilla | Chondrosarcoma | Low | N/A | N/A | − | − | − | 228 |

| 35 | M | Skull Base | Spindle cell sarcoma | High | C | N/A | − | + | + | 10 |

| 62 | F | Throat | Chondrosarcoma | High | S, C | Involved | + | − | + | 40 |

| 86 | M | Throat | Chondrosarcoma | High | N/A | N/A | − | − | + | 8 |

| 75 | F | Mandible | Osteosarcoma | High | S, R | Clear | − | − | − | 35 |

| 63 | F | Maxilla | Chondrosarcoma | High | S, R | Involved | − | − | − | 33 |

| 72 | M | Mandible | Osteosarcoma | High | S, C | Involved | + | − | + | 12 |

| 60 | M | Oral Cavity | Liposarcoma | High | R, C | N/A | − | − | − | 33 |

| 60 | F | Skull Base | Chondrosarcoma | High | S, R | Marginal | + | − | − | 30 |

| 21 | M | Maxilla | Chondrosarcoma | High | S, C | Involved | − | − | − | 92 |

| 56 | F | Skull Base | Spindle cell sarcoma | High | R | N/A | − | − | − | 26 |

| 67 | F | Maxilla | Osteosarcoma | High | R, C | N/A | − | − | − | 25 |

| 28 | M | Maxilla | Chondrosarcoma | High | S, R, C | Clear | + | + | − | 40 |

| 41 | M | Orbit | Synovial sarcoma | High | S, R | Involved | + | + | − | 272 |

| 38 | M | Skull Base | Chordoma | Low | S, R | Involved | + | − | − | 58 |

| 88 | M | Face | DFSP | Low | S, R, C | Involved | + | − | − | 114 |

| 71 | F | Face | Angiosarcoma | High | S, R, C | Marginal | + | + | + | 44 |

| 70 | M | Neck | UPS | High | S, R | Marginal | + | − | − | 246 |

| 76 | F | Mandible | Osteosarcoma | High | R, C | N/A | − | − | + | 11 |

| 50 | M | Maxilla | Chondrosarcoma | High | N/A | N/A | − | − | + | 10 |

| 80 | M | Neck | Spindle cell sarcoma | High | S, R | Clear | + | − | − | 20 |

| 53 | M | Neck | UPS | Low | S, R, C | Involved | + | − | + | 14 |

| 80 | M | Scalp | UPS | Low | S | Marginal | − | + | − | 15 |

C = chemotherapy; DFSP = dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans; F = female; M = male; R = radiotherapy; S = surgery; N/A = not applicable; UPS = undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma; + = yes; − = no.

Sarcomas

There were 13 soft tissue and 19 bone sarcomas. Anatomical location and histological subtypes were recorded (Table 1). The most prevalent sites were the maxilla and the skull base, with 6/32 cases of each (18.8%). There were a total of 13 different histological subtypes, with the most common being chondrosarcoma (25%, n=8), osteosarcoma (18.8%, n=6) and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (15.6%, n=5).

Histological grade

Histological grading was undertaken by sarcoma histopathologists using the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) System whereby, for the purposes of this study, grade 1 is low-grade and grade 2 or higher is classified as high-grade; 26/32 sarcomas were high-grade, with 6/32 classified as low-grade. See Table 2 for statistical summary tables.

Table 2 .

Analysis by grade

| Low-grade | High-grade | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 6 | 26 | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 60.33 (19.50) | 57.85 (20.34) | p=0.788 |

| Sex | p>0.999 | ||

| Male | 67% | 65% | |

| Female | 33% | 35% | |

| Managed operatively | 83% | 65% | p=0.637 |

| Sarcoma type | p=0.194 | ||

| Soft tissue | 67% | 35% | |

| Bone | 33% | 65% | |

| Metastases | 17% | 19% | p>0.999 |

| Adjuvant therapy | p=0.682 | ||

| None | 33% | 15% | |

| Chemotherapy | 17% | 23% | |

| Radiotherapy | 17% | 35% | |

| Chemo-radiotherapy | 33% | 27% | |

| Margins | p=0.426 | ||

| Clear | 20% | 47% | |

| Marginal | 20% | 24% | |

| Involved | 60% | 29% | |

| Recurrence | 60% | 59% | p=0.666 |

| Deaths | 17% | 35% | p=0.350 |

Treatment

Twenty-two out of 32 patients underwent surgical resection. See Table 3 and Figure 1 for a statistical summary and survival by surgical versus non-surgical intervention. Surgical intervention was associated with a statistically significant improvement in survival (p=0.0095**). Nine out of 22 had radiotherapy and surgery; 4/22 had chemotherapy and surgery; 6/22 had both radiotherapy and chemotherapy in addition to surgery. Only three out of 22 underwent surgery alone. There were no differences in the proportions of patients demonstrating known metastases or receiving adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy between the operative and non-operative groups. Separate analyses (data not shown) demonstrated that the method of adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy, irrespective of surgery, was not associated with any difference in survival (p=0.107), marginal status (p=0.343) or recurrence (p=0.326).

Table 3 .

Analysis by surgical intervention

| Non-operative | Operative | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 9 | 23 | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 58.67 (17.54) | 58.17 (21.12) | p=0.951 |

| Sex | p>0.999 | ||

| Male | 67% | 65% | |

| Female | 33% | 35% | |

| Grade | p=0.150 | ||

| Low | 0% | 26% | |

| High | 100% | 74% | |

| Sarcoma type | p>0.999 | ||

| Soft tissue | 44% | 39% | |

| Bone | 56% | 61% | |

| Metastases | 11% | 22% | p=0.648 |

| Adjuvant therapy | p=0.461 | ||

| None | 22% | 17% | |

| Chemotherapy | 33% | 17% | |

| Radiotherapy | 11% | 39% | |

| Chemo-radiotherapy | 33% | 26% | |

| Deaths | 56% | 22% | See Figure 1 |

Figure 1 .

Survival following surgical intervention

Marginal status

On marginal analysis: 40.9% had clear margins (n=9); 36.4% had involved margins (n=8); and 22.7% were deemed to be close or marginal (n=5). See Table 4 for a statistical summary. Combining the marginal and involved groups to create groups of patients with ‘clear’ and ‘non-clear’ margins had no effect on statistical outcome for any of the reported p-values.

Table 4 .

Analysis by marginal status

| Clear | Marginal | Involved | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 9 | 5 | 8 | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 54.22 (24.68) | 73 (9.381) | 54.75 (21.16) | p=0.247 |

| Sex | p=0.846 | |||

| Male | 67% | 60% | 75% | |

| Female | 33% | 40% | 25% | |

| Sarcoma type | p=0.605 | |||

| Soft tissue | 33% | 60% | 38% | |

| Bone | 66% | 40% | 63% | |

| Grade | p=0.426 | |||

| Low | 11% | 20% | 38% | |

| High | 89% | 80% | 63% | |

| Metastases | 22% | 40% | 13% | p=0.515 |

| Adjuvant therapy | p=0.343 | |||

| None | 11% | 40% | 0% | |

| Chemotherapy | 11% | 0% | 38% | |

| Radiotherapy | 44% | 40% | 38% | |

| Chemo-radiotherapy | 33% | 20% | 25% | |

| Recurrence | 44% | 60% | 75% | p=0.441 |

| Deaths | 11% | 20% | 38% | p=0.512 |

Survival

Local recurrence was noted in 13/32 (40.6%). Overall, 76.9% of all recurrences (n=10) were in high-grade sarcomas, with three recurrences in low-grade sarcomas. Thus, 38.5% (n=10) of the 26 patients with high-grade sarcoma had recurrences. Four out of 13 recurrences (30.8%) occurred in patients with clear marginal status. Overall, 18.8% of patients were found to have distant metastases (n=6). Ten out of 32 patients (31.3%) died at a mean time of 17.6 months from diagnosis. Fifty per cent of those with metastatic disease died (n=3); 23.1% of those with local recurrence died (n=3). Mean survival for the cohort of 32 patients was determined to be 69.5 months. Two-year and five-year overall survival (OS) rates were determined to be 75% and 64%, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2 .

Overall survival

Discussion

The dearth of clinical studies in the literature involving H&N sarcomas reflects their relatively rare nature.10 Although they comprise approximately 5–10% of all sarcomas, they only represent around 1% of all H&N tumours overall.5,6 Moreover, their heterogeneity, for example with histological subtype and clinical behaviour, renders comparative analysis between available studies more challenging.

As far as this study is concerned, the male to female ratio was almost 2:1 (21 male and 11 female patients). Many studies in the literature also report a male to female ratio of greater than 1.2 The mean age of the patients in this series is 58 years, which is consistent with studies available in the literature.11

Overall, 59.4% of sarcomas originated from bone (n=19) with the remaining 40.6% originating from soft tissue (n=13). However, on review of the literature, soft tissue sarcomas are in fact more common than bone sarcomas. One retrospective analysis conducted on over 12,000 patients over a 37-year period found that over 70% were soft tissue in origin.7,12 This reflects on the Oxford Sarcoma Service operating as one of only five nationally approved tertiary referral centres for the management of primary bone sarcomas (in addition to soft tissue sarcomas).

The majority of the studies in the literature report grade at diagnosis to be high-grade. This is concordant with the findings of this series in which 81.3% of sarcomas were high-grade, as per the AJCC System (n=26).2 The most prevalent histological subtypes of H&N sarcomas reported in the literature are undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS), osteosarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma.7,12,13 Despite this, the commonest subtype in this study was chondrosarcoma (25%, n=8), followed by osteosarcoma (18.8%, n=6) and UPS (15.6%, n=5). This may be explained by the small sample size with only 32 cases analysed.

Local recurrence was seen in the majority of patients with involved (75%, n=6) and close (60%, n=3) margins. However, recurrence was also seen in 44.4% of those with clear margins (n=4). The majority of recurrences were seen in those with high-grade sarcomas, but out of the 26 patients with high-grade sarcomas, recurrence was only noted in 38.5%, and this is favourable when compared with the literature, which shows recurrence rates closer to 50%.14–16

In this series, surgical intervention demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in survival (p=0.0095**). Of the recorded data points, there were no other differences between the operative and non-operative groups, including: histological grade, recurrence, age, presence of metastases, sex and method of adjuvant therapy. This would indicate a homogeneous distribution of the above confounders between the groups and, thus, excludes the possibility of another recorded factor driving a higher mortality in the non-operative group. Irrespective of operative status, there were no differences in survival, recurrence or marginal status between methods of adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy. Together, these observations present a compelling argument to support the operative management of H&N sarcomas, regardless of grade or presence of metastases.

Adjuvant radiotherapy is often used in high-grade sarcomas or when marginal analysis is close/involved and has been shown to confer benefit in terms of recurrence-free survival.8,10 However, administering radiotherapy can be challenging given the proximity of vital surrounding structures. Chemotherapy can be used as systemic treatment in patients with/at risk of metastatic disease, or as a palliative treatment in advanced disease deemed to be unresectable. It has been shown in meta-analyses to improve recurrence-free survival, but there is little evidence to suggest positive impact on OS.15,17 Proton beam therapy is not currently available in the United Kingdom through routine commissioning as a treatment option for H&N malignancies owing to a lack of clinical evidence. It is, however, offered on a named patient basis and is used selectively at specialist centres. Although the extent of its clinical efficacy is yet to be determined, some centres have shown promising results with proton beam therapy.18

In total, 31.3% patients have died to date at a mean time of 17.6 months from definitive diagnosis (n=10). Ninety per cent of mortalities were in those with high-grade sarcomas (n=9). Overall, 18.8% of patients were found to have metastatic disease at distant sites (n=6), which is comparable with rates found in the literature.19 Fifty per cent of those with metastatic disease died (n=3). The mean survival from date of diagnosis was determined to be 69.5 months. Following survival analysis, the rates of two-year and five-year OS were determined to be 75% and 64%, respectively. On review of data in the literature, the five-year OS of 64% in this series is comparable with figures reported from previous studies, which range from 31% to 87%.2,3,11,12,14,19,20

Although sarcomas are common in their mutual origin from embryonic mesenchyme, their capacity to exhibit clinically diverse courses can make their management particularly difficult.21 The significance of sarcoma specialists, not only surgeons but also radiologists, oncologists and histopathologists, cannot be overstated. Achieving negative margins in non-H&N sarcomas is much higher than in H&N sarcomas, 66% compared with 46% in the literature (40.9% in this series), and this has subsequent implications on local recurrence rates and OS.21,22 Cases of misdiagnosis by non-specialist histopathologists have previously been reported.23 There is a strong consensus towards the MDT-based approach in the literature.2,24 The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has emphasised the significance of early recognition and referral to a MDT.25 Thus, it is essential that patients with H&N sarcomas are managed at tertiary referral centres, where experienced MDTs can combine to deliver optimal patient outcomes.26

There are several limitations to this study. Although the cohort of 32 patients is comparable with many other studies, it is still a small sample size. This is confounded by the heterogeneity of the various histological subtypes, making comparative analysis more challenging. Furthermore, the retrospective nature limits the scope of evaluation. However, recent technological advancements are likely to have led to enhanced outcomes and these include: developments in immunohistochemistry to assist with diagnosis;20 advances in molecular genetic pathology leading to targeted therapies such as imatinib mesylate in the treatment of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans;27 and surgical innovations such as microvascular free flaps enabling enhanced resectability.28 Given the scarcity of large-scale studies pertaining to H&N sarcomas in the literature, it would be prudent to establish a prospective and contemporaneous national database in order to improve and optimise the long-term evaluation and management of these patients.29 Nonetheless, this study still adds value to the small number of studies on H&N sarcomas in the literature.

Conclusion

Outcomes for H&N sarcomas are generally inferior when compared with sarcomas of the extremities, trunk or retroperitoneum. Challenges encountered in management arise owing to the unique local anatomy, with the presence of vital nearby structures. Consequently, performing en bloc resection with negative margins and administering radiotherapy is difficult, with subsequent ramifications on local recurrence rates and prognosis. This, combined with their relatively low rate of incidence, means that optimal service delivery is essential. We would advocate for a fully integrated system in which H&N sarcomas are discussed alongside other sarcomas in a multidisciplinary approach, in order to maximise coordination between members of the sarcoma MDT. Close collaboration with H&N-specific MDTs is also vital. The necessity for prospectively maintained databases is warranted to facilitate large-scale, contemporary studies to be undertaken.

References

- 1.Stiller CA, Trama A, Serraino Det al. Descriptive epidemiology of sarcomas in Europe: report from the RARECARE project. Eur J Cancer 2013; 49: 684–695. 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Penel N, Mallet Y, Robin YMet al. Prognostic factors for adult sarcomas of head and neck. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2008; 37: 428–432. 10.1016/j.ijom.2008.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamaguchi S, Nagasawa H, Suzuki Tet al. Sarcomas of the oral and maxillofacial region: a review of 32 cases in 25 years. Clin Oral Investig 2004; 8: 52–55. 10.1007/s00784-003-0233-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ketabchi A, Kalavrezos N, Newman L. Sarcomas of the head and neck: a 10-year retrospective of 25 patients to evaluate treatment modalities, function and survival. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2011; 49: 116–120. 10.1016/j.bjoms.2010.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeVita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA. Cancer: Principles & Practice of Oncology. 11th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorsky M, Epstein JB. Head and neck and intra-oral soft tissue sarcomas. Oral Oncol 1998; 34: 292–296. 10.1016/S1368-8375(98)80010-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shellenberger TD, Sturgis EM. Sarcomas of the head and neck region. Curr Oncol Rep 2009; 11: 135–142. 10.1007/s11912-009-0020-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tran LM, Mark R, Meier Ret al. Sarcomas of the head and neck. prognostic factors and treatment strategies. Cancer 1992; 70: 169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kraus DH, Dubner S, Harrison LBet al. Prognostic factors for recurrence and survival in head and neck soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer 1994; 74: 697–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mücke T, Mitchell DA, Tannapfel Aet al. Outcome in adult patients with head and neck sarcomas—a 10-year analysis. J Surg Oncol 2010; 102: 170–174. 10.1002/jso.21595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peng KA, Grogan T, Wang MB. Head and neck sarcomas: analysis of the SEER database. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014; 151: 627–633. 10.1177/0194599814545747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huber GF, Matthews TW, Dort JC. Soft-tissue sarcomas of the head and neck: a retrospective analysis of the Alberta experience 1974 to 1999. Laryngoscope 2006; 116: 780–785. 10.1097/01.MLG.0000206126.48315.85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mendenhall WM, Mendenhall CM, Werning JWet al. Adult head and neck soft tissue sarcomas. Head Neck 2005; 27: 916–922. 10.1002/hed.20249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh RP, Grimer RJ, Bhujel Net al. Adult head and neck soft tissue sarcomas: treatment and outcome. Sarcoma 2008; 2008: 654987. 10.1155/2008/654987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tejani MA, Galloway TJ, Lango Met al. Head and neck sarcomas: a comprehensive cancer center experience. Cancers (Basel) 2013; 5: 890–900. 10.3390/cancers5030890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guadagnolo BA, Zagars GK, Raymond AKet al. Osteosarcoma of the jaw/craniofacial region: outcomes after multimodality treatment. Cancer 2009; 115: 3262–3270. 10.1002/cncr.24297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adjuvant chemotherapy for localised resectable soft-tissue sarcoma of adults: meta-analysis of individual data. Sarcoma meta-analysis collaboration. Lancet 1997; 350: 1647–1654. 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)08165-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gutiontov SI, Zumsteg ZS, Lok BHet al. Proton radiation therapy for local control in a case of osteosarcoma of the neck. Int J Part Ther 2017; 3: 421–428. 10.14338/IJPT-16-00015.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barosa J, Ribeiro J, Afonso Let al. Head and neck sarcoma: analysis of 29 cases. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis 2014; 131: 83–86. 10.1016/j.anorl.2012.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Bree R, van der Waal I, de Bree Eet al. Management of adult soft tissue sarcomas of the head and neck. Oral Oncol 2010; 46: 786–790. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cormier JN, Pollock RE. Soft tissue sarcomas. CA Cancer J Clin 2004; 54: 94–109. 10.3322/canjclin.54.2.94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zagars GK, Ballo MT, Pisters PWet al. Prognostic factors for patients with localized soft-tissue sarcoma treated with conservation surgery and radiation therapy: an analysis of 1225 patients. Cancer 2003; 97: 2530–2543. 10.1002/cncr.11365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis EC, Ballo MT, Luna MAet al. Liposarcoma of the head and neck: The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center experience . Head Neck 2009; 31: 28–36. 10.1002/hed.20923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kraus DH. Sarcomas of the head and neck. Curr Oncol Rep 2002; 4: 68–75. 10.1007/s11912-002-0050-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Sarcoma. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs78/resources/sarcoma-2098854826693.

- 26.Makary RF, Gopinath A, Markiewicz MRet al. Margin analysis: sarcoma of the head and neck. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 2017; 29: 355–366. 10.1016/j.coms.2017.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.García JJ, Folpe AL. The impact of advances in molecular genetic pathology on the classification, diagnosis and treatment of selected soft tissue tumors of the head and neck. Head Neck Pathol 2010; 4: 70–76. 10.1007/s12105-009-0160-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoffman HT, Robinson RA, Spiess JLet al. Update in management of head and neck sarcoma. Curr Opin Oncol 2004; 16: 333–341. 10.1097/01.cco.0000127880.69877.75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Neill JP, Bilsky MH, Kraus D. Head and neck sarcomas: epidemiology, pathology, and management. Neurosurg Clin N Am 2013; 24: 67–78. 10.1016/j.nec.2012.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]