Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the effect(s) of MTA on in vitro RANKL-mediated osteoclast dependent bone resorption events and on the influence of Ca2+ and Al3+ on the osteoclastogenesis inhibition by MTA.

Materials and Methods:

Two types of osteoclast precursors, RAW 264.7 (RAW) cell line or bone marrow cells (obtained from BALB/c mice and stimulated with recombinant (r) M-CSF), were stimulated with or without RANKL, with or without MTA for 6 to 8 days. White Angelus MTA and Bios MTA (Angelus, Londrina, Paraná, Brazil) were prepared and inserted into capillary tubes (direct contact surface = 0.50mm2 and 0.01mm2). Influence of MTA on these types of osteoclast precursors was measured by the number of differentiated tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP)-positive multinuclear cells (RAW and bone marrow cells), TRAP enzyme activity (RAW cells), cathepsin K gene expression (RAW cells) and resorptive pit formation (RAW cells) by mature osteoclasts. Besides, RAW cells were also stimulated with Ca2+ and Al3+ to evaluate the influence of these molecules on MTA anti-osteoclastogenic potential.

Results:

In bone marrow and RAW cells, the number of TRAP-positive mature osteoclast cells induced by rRANKL was significantly inhibited by the presence of MTA compared to control rRANKL stimulation without MTA (p<0.05), along with the reduction of TRAP enzyme activity (p<0.05) and the low expression of cathepsin K gene (p<0.05). In contrast, to control mature osteoclasts, the resorption area on dentin was significantly decreased for mature osteoclasts incubated with MTA (p<0.05). rRANKL-stimulated RAW cells treated with Ca2+ and Al3+ decreased the number of osteoclasts cells. Besides, the aluminum oxide was the dominant suppressor of the osteoclastogenesis process.

Conclusions:

MTA significantly suppressed RANKL-mediated osteoclastogenesis, osteoclast activity and, therefore, appears able to suppress bone resorptive events in periapical lesions. This process might be related to Ca2+ and Al3+ activities.

Clinical relevance:

MTA is an important worldwide biomaterial. The knowledge about its molecular activities on osteoclasts might contribute to improving the understanding of its effective clinical results.

Keywords: Mineral Trioxide Aggregate, osteoclastogenesis, RANKL, Calcium, Aluminum

Introduction

Periapical lesions are destructive inflammatory pathologies and immune response against microorganisms that affect the periapical periodontium. They are characterized by periradicular periodontal ligament and bone destruction as a consequence of bacterial infection of the dental pulp [1]. This way, diverse inflammatory mediators, such as Interleukin (IL)-1, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), nitric oxide (NO), interferon (IFN)-gamma, prostaglandins, and metalloproteinases - have been associated with periradicular lesions [1–3].

Receptor Activator of Nuclear factor Kappa B (RANK), a hematopoietic surface receptor, has been identified as a critical regulator of bone [4] and calcium metabolism. RANK ligand (RANKL) is a protein produced by osteoblasts, cells of bone stroma and activated by T lymphocytes [5] and it is classified into the superfamily of TNF and TNF receptor. RANKL is a cytokine involved in both the physiological and pathological regulation of osteoclastogenesis and osteoclast activation [6]. The activation of RANK by its ligand leads to the expression of osteoclast-specific genes during differentiation, the activation of resorption by mature osteoclasts, and their survival and participation in new rounds of bone degradation at neighboring sites [7].

Mineral Trioxide Aggregate (MTA) is a root-end filling material developed by Mahamoud Torabinejad [8] as a powder composed by tricalcium silicate, bismuth oxide, dicalcium silicate, tricalcium aluminate, tetracalcium aluminoferrite, and calcium sulfate dehydrate. Bios MTA (Angelus, Londrina, Brazil) is completely synthesized in the laboratory with high-quality control and free from contamination, especially of arsenic [9]. It also presents a higher percentage of Al2O3 and free CaO.

In this sense, mineralized tissue formation has been described in periapical lesion repair after the use of MTA [10]. On the other side of the repair process, it has also been shown that ProRoot MTA demonstrated an inhibitory effect on osteoclast differentiation and function via inhibition of ERK signaling pathways and IκB phosphorylation [11]. Despite the satisfactory clinical results, including mineralized tissue formation and osteoclast inhibition, little is known about how this process happens. One hypothesis is that the presence of some elements from MTA on the periapical area can stimulate osteoblast activity while inhibiting osteoclast activity. Atomic spectroscopy analysis of distilled water incubated with MTA for 72 hours reveals that aluminum and calcium were the prevalent ions released [12]. Based on these effective clinical results with MTA, we hypothesize that this anti-osteoclastogenic activity might be mediated by aluminum and calcium activities. Thus, this study aimed to evaluate the in vitro effect(s) of MTA on osteoclasts, to confirm if these both chemical elements are the key factors to inhibit osteoclastogenesis.

Materials and methods

MTA preparation

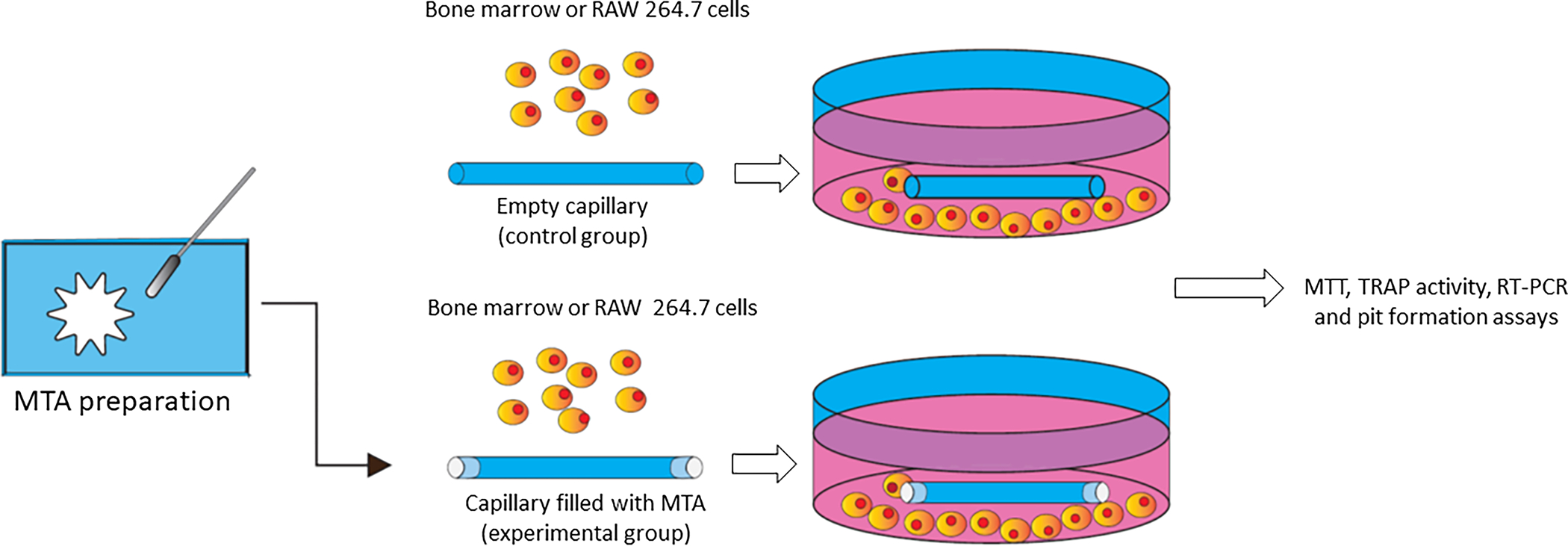

White Angelus MTA and Bios MTA (Angelus, Londrina, Paraná, Brazil) were prepared in accordance with manufacturers’ instructions in sterile conditions. After preparation, MTA was inserted into the tips of previously sectioned and sterilized capillary tubes (test group), so that the contact surface with the cell suspension could be standardized (area = 0.50mm2 and 0.01mm2 for the cultures realized in 24-well plates and 96-well plates respectively), according to previously published studies [13, 14]. Empty capillary tubes were used in control cultures (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Schematic demonstration of MTA preparation and its filling into capillary tubes. These capillaries were inserted into 24 well plates and cultivated with bone marrow or RAW 264.7 cells. Control group was represented by empty capillary tubes.

Animals

Male and female BALB/c mice were obtained from the Forsyth Institute (Boston, MA, USA). Animals were kept in a conventional cage and maintained at controlled ambient temperature. Food and water were offered to animals ad libitum. The protocol for this animal experiment was approved by The Forsyth Institute’s animal ethics committee.

RAW cells culture

Non-confluent culture of RAW 264.7 osteoclast precursor (RAW) cell line (from ATCC) was harvested and cultured with minimum essential medium eagle alpha modification (alpha-MEM) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 2.2 G.L−1 NaHCO3 (Sigma), 15% fetal calf serum (Altana, Lawrenceville, GA, USA), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (1000 U/mL) (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA), 1% MEM amino acids solution (Invitrogen), 1% L-glutamine (Invitrogen) and 0.1% gentamycin (Invitrogen). Cells (2×105) were cultured in a 24-well plate (Corning, New York, NY, USA) with capillaries with or without MTA, for 24 hours for cell viability assay. Another culture was performed, including 2-capillaries/well with or without MTA, for 24 hours. In order to observe osteoclast differentiation, 100ng.mL−1 of recombinant (r) RANKL (Peprotech, Rock Hill, NJ, USA) was added to this culture, and every three days, half of medium and rRANKL (Peprotech) were changed, and the cultures were harvested on days 5, 6 and 8. RNA extractions were performed after 48h of cell incubation. The evaluation of the effect of aluminum and calcium on osteoclastogenesis was performed through RAW cells incubation with or without 40μg.mL−1 of aluminum oxide, 99.99% (Sigma) and calcium oxide Reagent Plus, 99.99% (Sigma), with/without rRANKL for 7 days.

Bone marrow cells culture

Bone marrow cells were recovered by flushing Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen) supplemented with 0.0001% of gentamycin (Invitrogen) and 0.002% Fungizone amphotericin B (Invitrogen) into the femur and tibia marrow space of BALB/c mice [15]. The culture was washed twice with DMEM (Invitrogen) and separated from blood cells and lymphocytes by Histopac 1083 (Sigma). The culture was washed twice in alpha-MEM medium (Sigma) supplemented as above. Cells (2.5×106 cells.mL−1) were cultured with 100 ng.mL−1 of rRANKL (Peprotech), 10 ng.mL−1 of rM-CSF (Peprotech) and capillaries with or without MTA, per 6 days. Half of the medium was changed on day 3 by replacing with half of a new medium and new rM-CSF (Peprotech) and rRANKL (Peprotech).

MTT assay

The half of medium was removed from the culture, and it was incubated with MTT solution (Sigma) in an incubator, per 4 hours. 0.04 N HCl in isopropanol was added in the culture, and the formazan crystals were dissolved by pipetting. The culture was transferred to a 96-well plate (Corning), and the color was read in ELISA reader (Biokinetics reader, Bio-tek instruments, Winooski, Vermont, USA) at 575 nm. Results were expressed in optical density after subtracting the blank’s optical density.

Tartrate-resistant acidic phosphatase (TRAP) stain

Cells were fixed with 5% formalin-saline, per 20 minutes. Then, cells were washed with PBS 4 times and incubated with 150 mM tartrate (pH 5.5) for 2 hours, at room temperature. Acid phosphatase substrate was added, and the cultures were further incubated for 2 hours, to develop red color. Methyl green was used to counterstain cell nuclei. Differentiated osteoclasts were identified as tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) positive cells with three or more nuclei. Each well of 24-well plate was divided into four quadrants, and differentiated osteoclasts of one of these quadrants were counted. In the 96-well plate, the number of these cells were counted in the totality of the well [16].

TRAP activity

Twenty-five microliters of lysed cells and a standard curve of TRAP (Sigma), each one in different lines, were incubated with 225 μL TRAP buffer (150 mM Tartrate buffer and 2 mM MgCl2) and 1 mg.mL−1 of phosphatase substrate (Sigma), per 90 minutes. 50 μL of 2 N NaOH was added to the plate to stop the reaction, and the optical density was observed in the ELISA reader (Biokinetics reader, Bio-tek Instruments) (405 nm).

Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from RAW cells after 48 hours of incubation with or without rRANKL (Peprotech) and MTA using RNA-Bee (Tel-Test, Friends Wood, TX, USA). One microgram of cDNA was reversed transcribed using SuperScriptTM II RT (Invitrogen), 0.1 M DTT (Invitrogen) and 25 mM dNTP (TaKaRa Bio Inc., Otsu, Shiga, Japan). cDNA was amplified using the TaKaRa Ex Taq System (TaKaRa Bio Inc.). Sequences of specific primer sets were as follows: β actin (housekeeping gene): sense 5’-GACGGGGTCACCCACACTGT-3’, anti-sense 5’-AGGAGCAATGATCTTGATCTTC-3’; cathepsin K: sense 5’-CTGAAGATGCTTTCCCATATGTGGG-3’, anti-sense 5’-GCAGGCGTTGTTCTTATTCCGAGC-3’. An optimized protocol of thermal cycling was used: 94°C for 2min, followed by 35 cycles of 98°C for 10s, 50°C for 30s, and 72°C for 60s, and a final extension at 72°C for 7min, using a MJ Research PTC-200 Thermal Cycler (MJ Research inc). PCR products were separated in 1.5% agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide (Sigma). The results were expressed as a ratio between the optical densitometry of cathepsin K gene expression signal/β-actin gene expression signal, using the NIH image software analyzer.

Pit Formation assay

RAW cells were cultured as described above with 100 ng.mL−1 of rRANKL (Peprotech) in a plate coated with type I rat tail collagen (BD Biosciences Bedford, MA, USA) and 0.02 N acetic acid (Fisher, Trenton, NJ, USA) until osteoclasts were differentiated. Cells were harvested with trypsin-EDTA (Invitrogen) and the cellular concentration adjusted to 4×105 cells/well. Cells were applied onto dentin slices (Immunodiagnostic systems, Boldon, UK), with 100 ng.mL−1 of rRANKL (Peprotech) and capillaries with or without MTA. After osteoclast differentiation, dentin slices were stained with toluidine blue 1% (Fisher). Four pictures were taken from each group, and the reabsorbed pit area was counted in these pictures using the NIH image software analyzer at a 100-fold magnification.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were carried out in technical and biological triplicates. Statistical analyses were performed by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test followed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Bonferroni post hoc by using GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA); p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Effect of MTA on osteoclast differentiation induced by rRANKL in RAW and bone marrow cells

First, the effect of MTA on the osteoclast precursor cell line RAW 264.7 viability was observed. MTA did not affect RAW 264.7 viability when compared to the control group (Figure 2A). An induced-rRANKL osteoclastogenesis model was used to verify the effect of MTA on the osteoclast differentiation. The addition of rRANKL into the RAW 264.7 (Figure 2B and photos D–I) and BALB/c bone marrow cell culture medium increased the number of osteoclasts differentiated cells (Figure 2C p<0.0001and photos J–O).

Figure 2:

MTA effects on osteoclast differentiation. MTT viability assay with RAW cells (A), number of TRAP-positive cells differentiated from RAW 264.7 cells (B) or bone marrow cells (C) by stimulation with 100 ng.mL−1 of rRANKL and 100 ng.mL−1 of rRANKL associated with 10 ng.mL−1 of rM-CSF, respectively, in contact with MTA filled capillaries, after 8 days. Columns and bars indicate the mean and SD of triplicates, respectively, of one representative experiment. # (p<0.0001) indicates, statistical differences when compared to the control group only with the medium. Statistical differences were represented by * (p<0.05), ** (p<0.001) **** (p<0.0001). Representative photos of trap positive stain cells induced by RAW cells (D-I) and bone marrow cells (J-O). Scale bar: 100 μm. Kinetic of osteoclast differentiation from day 5 to day 8 in RAW cell cultures stimulated with 100 ng.mL−1 of rRANKL (P). * indicates, statistical differences (p<0.05) when compared with Angelus MTA and Bios MTA. # indicates p<0.0001, when compared with Bios MTA. The number of nuclei/TRAP-positive cells (Q) in RAW cell cultured with 100 ng.mL−1 of rRANKL. No statistical difference was found between triplicates of all groups.

Besides, MTA did suppress the number of TRAP-positive mature osteoclast cells induced by rRANKL, in both RAW 264.7 cells (Control: 302 cells±33.17, Angelus MTA: 213.17 cells±34.52, Bios MTA: 175.17 cells±20.35 p<0.0001) and bone marrow cells (Control: 219.33 cells±11.02, Angelus MTA: 168 cells±30.61, Bios MTA: 183 cells±15.28 p<0.05, p<0.01), after 8 days. The suppression of TRAP-positive stain cells in RAW 264.7 cells culture by MTA was observed from day 5 to day 8 (Figure 2P). In all incubation time points, cultures with MTA presented a lower number of osteoclasts. On day 8, Bios MTA significantly decreased the number of TRAP-positive cells when it was compared with Angelus MTA (Angelus MTA: 53 cells±1.41, Bios MTA: 27.33 cells±3.06, p<0.0001).

Despite this MTA effect on the osteoclastogenesis, when the number of nuclei/osteoclast cell was counted, no statistical differences were found between the cultures with or without MTA in any incubation time points (Figure 2Q). These data indicated that, after the multinucleated cells were recruited by the action of RANKL and had adhered to the bone in a resorption area, both MTAs could inhibit the cytodifferentiation process to the mature osteoclasts.

Effect of MTA on the osteoclast function

Three parameters were analyzed: TRAP activity, cathepsin K gene expression and reabsorbed pit area, using the same model of osteoclastogenesis. Regarding same effects of MTA were observed in the downregulation of osteoclastogenesis based on RANKL-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells and RANKL-stimulated bone marrow cells, RAW 264.7 cells were chosen for the next steps.

After osteoclast differentiation, RANKL stimulates osteoclast activation, which includes the activation of TRAP and cathepsin K for subsequent bone resorption. The addition of rRANKL into the cell culture medium increased TRAP activity (p<0.05) and cathepsin K expression (p<0.05). MTA did suppress TRAP activity (Control: 1.26 μg.mL−1±0.07, Angelus MTA: 0.38 μg.mL−1±0.11, Bios MTA: 0.16 μg.mL−1±0.03, p<0.0001) (Figure 3A) induced by rRANKL. RAW 264.7 cells stimulated with rRANKL in the presence of Bios MTA presented lower TRAP activity than the same culture with Angelus MTA (p<0.001). The housekeeping gene β-actin adjusted Cathepsin K expression. MTA suppressed cathepsin K gene expression in groups with or without rRANKL. In samples incubated with rRANKL, MTA suppressed cathepsin K gene expression to 9% comparing to the control group (Figure 3B and 3C).

Figure 3:

MTA effects on osteoclast function. TRAP activity (A) induced from RAW 264.7 cells by stimulation or not with 100 ng.mL−1 of rRANKL, in contact with MTA filled capillaries, per 6 days. Columns and bars indicate the mean and SD of triplicates, respectively, of one representative experiment. # (p<0.0001) indicates, statistical differences when compared to the group only with the medium. ** (p<0.001) **** (p<0.0001) indicate, differences related to β-actin (housekeeping gene) and cathepsin K gene expression (B) by RAW 264.7 cells stimulated with 100 ng.mL−1 of rRANKL or cultured in medium without rRANKL, in contact with MTA for 48 hours. Columns indicate the ratio between cathepsin K gene expression/β-actin gene expressions (C). Resorpted pit area (D) induced from mature osteoclasts stimulated with 100 ng.mL−1 of rRANKL, in contact with MTA filled capillaries. Columns and bars indicate the mean and SD of triplicates, respectively, of one representative experiment. # indicates, statistical differences (p<0.0001), when compared to the control without rRANKL. * (p<0.05), ** (p<0.001), **** (p<0.0001), indicate significative differences. Representative photos of pit formation induced (E-H) by mature osteoclasts. Scale bar: 100 μm.

As a consequence of osteoclast function, the third parameter analyzed was the area absorbed by mature osteoclasts. Again, the addition of the rRANKL to cell cultures increased the reabsorbed pit area (p<0.0001). Addition of both MTAs to the mature osteoclast culture, previously differentiated by rRANKL stimuli on RAW 264.7, reduced the resorptive pit area compared to the cultures in the absence of MTA (rRANKL+Control: 0.266 cm2±0.07, rRANKL+Angelus MTA: 0.115 cm2±0.05, rRANKL+Bios MTA: 0.035 cm2±0.01, p<0.01 p<0.0001) (Figure 3D–H). Not only the total resorptive pit area was smaller in groups with MTA, but also the size of each pit area was smaller in this group (Figure 3E–H). Comparing both MTAs, Bios MTA presented the lowest reabsorbed pit area (p<0.05), similar to the control group without rRANKL. These data indicated that MTA had an effect on the osteoclast activity and probably presented some protective action in periapical lesions through new resorptive events and that Bios MTA presented better results than Angelus MTA.

Effect of calcium oxide and aluminum oxide on the rRANKL mediated osteoclastogenesis

Once has been demonstrated that MTA releases aluminum and calcium ions in solution [12], the effect of these two ions on RAW 264.7 osteoclast precursor cell line stimulated with rRANKL was analyzed. The used concentration of calcium and aluminum oxide was based on previous data, that demonstrate the release of 0.49 mg/dL−1 of calcium ions, after 7 days [17]. Then, using the same model described above, both ions reduced RANKL-mediated osteoclastogenesis (Figure 4A). Aluminum oxide was the major suppressor of osteoclast cells differentiation (Control: 236±12.49 cells; calcium oxide: 101.67±7.23 cells; aluminum oxide: 80.33±4.73 cells, p<0.01 p<0.0001). This result indicates that calcium and aluminum ions released by aluminum oxide and calcium oxide suppress RANKL-mediated osteoclastogenesis (Figure 4B). The previous information regarding the release of these ions by MTA [12], can be one of the protective mechanisms of this material on the periapical resorptive events, which has permitted the successful use of MTA in apical lesions.

Figure 4:

Effect of calcium oxide and aluminum oxide on rRANKL-mediated osteoclastogenesis. The number of TRAP-positive stained cells induced from RAW 264.7 cells (A) by stimulation with 100 ng.mL−1 of rRANKL, in contact with MTA filled capillaries. # indicates, statistical differences (p<0.0001), when compared to the RAW cells without rRANKL. ** (p<0.001) and **** (p<0.0001) indicate significative differences. Representative scheme of how the release of calcium and aluminum ions, by MTA, can affect the differentiation and activity of mature osteoclasts (B).

Discussion

Receptor activator of nuclear factor kB-ligand (RANKL) is a bone-resorptive cytokine and an essential molecule in all phases of the osteoclast’s life span. It has been catalogued as a key regulator of the physiological and pathological control of bone metabolism [6]. RANKL has been associated with diverse pathologies characterized by bone destruction, such as rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis, Paget’s disease, bone tumors, osteolytic facial lesions and periodontitis [18]. It has been proposed as the common final pathway of the bone-resorptive and regulatory cytokines, in osteoclast differentiation and activation and in bone resorption. RANK and RANKL-deficient mice exhibit severe osteopetrosis, characterized radiographically by opacity in long bones, vertebral bodies, and ribs and by significantly increased total and trabecular bone density [19].

In this sense, bone resorption starts with the recruitment of the multinucleated polykaryons by the CSF-1 and RANKL action, their adherence to the bone and cell-differentiation into mature osteoclasts. Osteoclast activity is initiated by RANKL-stimulated induction of protons and lytic enzymes secretion into the sealed resorption vacuole formed between the basal surface of the osteoclast and the bone surface. Acidification of this compartment by secretion of protons leads to the activation of TRAP and cathepsin K, the two primary enzymes responsible for the degradation of bone mineral and collagen matrices, leading to bone resorption [20]. MTA affects both phases of osteoclast life span: the osteoclast differentiation and osteoclast function.

MTA did not affect the viability of RAW 264.7 osteoclast precursor cell line, and this biocompatibility was described for other different cell types [13, 21–25]. Despite the biocompatibility of this material, MTA decreased the number of osteoclasts differentiated from osteoclast precursor cell line and BALB/c bone marrow cells stimulated with rRANKL, but it did not affect the number of nuclei/osteoclast cells. The reduction of the number of differentiated osteoclast cells by the presence of MTA was observed from day 5 to day 8. On day 8, Bios MTA presented better results than Angelus MTA.

Analyzing the osteoclast function, MTA suppressed TRAP activity and cathepsin K gene expression. Cathepsin K is a proteolytic enzyme that cleaves helical and telopeptide regions of collagen in an acidic environment [26]. Cathepsin K is expressed in and secreted by osteoclasts near the ruffled border with its expression being promoted by RANKL [26]. It is a promising target for interrupting osteoclast function; cathepsin K knockout mice display marked osteopetrosis [27] and its overexpression results in enhanced bone resorption [28].

MTA also suppressed TRAP activity. TRAP is involved in the degradation of bone constituents by osteoclasts, as demonstrated by incubation of osteoclasts with anti-TRAP antibodies, which resulted in the reduction of bone resorption [29, 30]. Besides, TRAP activation is not affected by the absence of cathepsin K, as it was observed in osteoclasts isolated from cathepsin K knockout mice [31]. As a consequence of the osteoclast activity downregulation, the resorpted pit area by mature osteoclasts was smaller in the presence of MTA.

All these MTA results were following previous data that showed that MTA acts on bone remodeling, particularly osteoclast differentiation. It has been shown that MTA extracts inhibited osteoclast differentiation via preventing the fusion of osteoclast precursors and interrupted RANKL-induced acidic vesicular organelle formation and autophagic vacuole appearance in osteoclast precursors [32]. It is also observed that 60 days after MTA-sealed perforation, the number of osteoblasts was higher in MTA groups [33]. Hashigushi et al. [34] observed that MTA might be related to the downregulation of MMP9, an important enzyme involved in bone reabsorption.

In order to understand the mechanism by which MTA acts to down-modulate osteoclast differentiation and function, we analyzed previously publications related to its mineral composition and release of ions in the extraction solution. It was demonstrated that calcium (405.23 mg/L) and aluminum (25.42 mg/L) ions were released in solution after MTA exposure [12, 35]. It is known that high extracellular calcium concentration modulates osteoclast differentiation and function [36], and that osteoclastic bone resorption is directly regulated by calcitonin and, locally, by ionized calcium (Ca2+) generated as a result of osteoclastic bone resorption. This fact was confirmed when freshly isolated rat osteoclasts were settled onto bone slices and incubated in a high Ca2+ concentration (5–20 mM), which resulted in a dramatic and concentration-dependent reduction in their bone-resorption activity [37]. Parallel to this, the elevation of the extracellular calcium concentration causes a dramatic reduction of cell size, accompanied by a marked diminution of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase in a dose-dependent manner within an hour of exposure to high Ca2+ concentrations and the abolition of bone resorption [38]. Interestingly, resorpting osteoclasts produced lower quantities of acid phosphatase than those plated on plastic, suggesting that locally produced Ca2+ may inhibit enzyme secretion [30]. In all these experiments, Ca2+ was added extracellularly after osteoclasts were plated onto the devitalized bone. It was demonstrated that the addition of 10% CaCl2 to MTA improved its sealing properties [39], increased pH of the preparation, required less water for settling and increased calcium release [40], which could suppress bone reabsorption.

On the other hand, aluminum oxide (Al2O3), also present in the MTA composition, is a standard adjuvant used in vaccines [41] and it is also used as a ceramic-on-ceramic hip prosthesis used in orthopedic surgery for total hip replacement in patients affected by hip osteoarthritis [42, 43]. In this kind of surgery, 60–70% of hip arthroplasties ultimately fail due to bone loss around the implant due to bone resorption and ultimately aseptic loosening of the prosthesis. Granchi et al. [43] observed that supernatant of human osteoblasts with Al2O3 showed a decrease in c-fos expression together with an unchanged expression of c–src, suggesting that the passage of macrophages into osteoclast lineage has deviated. In that study, the authors observed that prosthesis that did not have aluminum oxide in its constitution produced higher levels of RANKL [43].

It was demonstrated that the MTA release of calcium and aluminum ions in the solution [12], and we hypothesize that this action was related to the presence of these two ions. The downregulation of osteoclast differentiation confirmed this fact in the presence of calcium and aluminum oxide. It is also known that the release of calcium in MTA extract solutions is much higher than that of aluminum [12]. However, we observed that downregulation of osteoclast differentiation was more effective when aluminum oxide was added in the solution together with calcium oxide than calcium oxide alone. An additional support to our hypothesis is the fact that Bios MTA presents 6% aluminum oxide in its composition, while Angelus MTA presents only 4% and Bios MTA also present a higher percentage of free CaO than Angelus MTA. This fact can justify the higher downregulation of TRAP and the smaller resorptive pit area in cultures with Bios MTA when compared to Angelus MTA. The addition of high quantities of aluminum oxide in the MTA composition can be beneficial in avoiding bone resorption.

This way, the MTA effect on the osteoclast activity, and its clinical result observed on the resorpted bone areas, might be related to the release of Ca2+ and Al3+. Thus, the healing process promoted by MTA in the periapical bone loss area involves not only the mineralized tissue formation that results in periapical lesions repair [10] but also the suppression of the osteoclast differentiation and osteoclast function.

Conclusion

In summary, we demonstrated that MTA down-regulated osteoclast differentiation, and osteoclast function (TRAP activity, cathepsin K gene expression and resorpted pit area). Besides, we have shown that calcium and aluminum ions are most likely the active components of MTA effects on osteoclasts. The use of MTA is recommended in perirradicular area associated to bone resorption, once it stimulates mineralized tissue formation and down-regulation of osteoclast differentiation and function.

Acknowledgments

Angelus (Londrina, PR, Brazil) kindly provided by Angelus and Bios MTA.

Funding

This work was supported by Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG), by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) and NIH NIDCR R15 grant DE027851. LQV and APRS are CNPq fellows. TMBR was a CAPES scholarship holder.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Taia Rezende declares no conflict of interest. Antonio Sobrinho declares that he has no conflict of interest. Leda Vieira declares that she has no conflict of interest. Mauricio Sousa declares that he has no conflict of interest. Toshihisa Kawai declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by The Forsyth Institute’s animal ethics committee.

Informed consent

Informed consent: For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

References

- 1.Stashenko P, Teles R, D’Souza R (1998) Periapical inflammatory responses and their modulation. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 9:498–521. 10.1177/10454411980090040701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawashima N, Stashenko P (1999) Expression of bone-resorptive and regulatory cytokines in murine periapical inflammation. Arch Oral Biol 44:55–66. 10.1016/S0003-9969(98)00094-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silva MJB, Kajiya M, Alshwaimi E, et al. (2012) Bacteria-reactive immune response may induce RANKL-expressing T cells in the mouse periapical bone loss lesion. J Endod 38:346–350. 10.1016/j.joen.2011.12.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lacey DL, Timms E, Tan HL, et al. (1998) Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell 93:165–176. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81569-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vernal R, Dezerega A, Dutzan N, et al. (2006) RANKL in human periapical granuloma: Possible involvement in periapical bone destruction. Oral Dis 12:283–289. 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01191.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takahashi N, Udagawa N, Suda T (1999) A new member of tumor necrosis factor ligand family, ODF/OPGL/TRANCE/RANKL, regulates osteoclast differentiation and function. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 256:449–455. 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang YH, Heulsmann A, Tondravi MM, et al. (2001) Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF) stimulates RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis via coupling of TNF type 1 receptor and RANK signaling pathways. J Biol Chem 276:563–568. 10.1074/jbc.M008198200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torabinejad M, Watson TF, Pitt Ford TR (1993) Sealing ability of a mineral trioxide aggregate when used as a root end filling material. J Endod 19:591–595. 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)80271-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lara V de PL, Cardoso FP, Brito LCN, et al. (2015) Experimental furcal perforation treated with MTA: Analysis of the cytokine expression. Braz Dent J 26:337–341. 10.1590/0103-6440201300006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Camilleri J, Pitt Ford TR (2006) Mineral trioxide aggregate: A review of the constituents and biological properties of the material. Int. Endod. J. 39:747–754. 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2006.01135.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim M, Kim S, Ko H, Song M (2019) Effect of ProRoot MTA® and Biodentine® on osteoclastic differentiation and activity of mouse bone marrow macrophages. J Appl Oral Sci 27:. 10.1590/1678-7757-2018-0150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomson PL, Grover LM, Lumley PJ, et al. (2007) Dissolution of bio-active dentine matrix components by mineral trioxide aggregate. J Dent 35:636–642. 10.1016/j.jdent.2007.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rezende TMB, Vargas DL, Cardoso FP, et al. (2005) Effect of mineral trioxide aggregate on cytokine production by peritoneal macrophages. Int Endod J 38:896–903. 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2005.01036.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rezende TM, Vieira LQ, Sobrinho AP, et al. (2008) The influence of mineral trioxide aggregate on adaptive immune responses to endodontic pathogens in mice. J Endod 34:1066–1071. 10.1016/j.joen.2008.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamaguchi T, Movila A, Kataoka S, et al. (2016) Proinflammatory M1 macrophages inhibit RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis. Infect Immun 84:2802–2812. 10.1128/IAI.00461-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawai T, Eisen-Lev R, Seki M, et al. (2000) Requirement of B7 Costimulation for Th1-Mediated Inflammatory Bone Resorption in Experimental Periodontal Disease. J Immunol 164:2102–2109. 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.2102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Özdemir HÖ, Özçelik B, Karabucak B, Cehreli ZC (2008) Calcium ion diffusion from mineral trioxide aggregate through simulated root resorption defects. Dent Traumatol 24:70–73. 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2006.00512.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taubman MA, Kawai T (2001) Involvement of T-lymphocytes in periodontal disease and in direct and indirect induction of bone resorption. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 12:125–135. 10.1177/10454411010120020301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dougall WC, Glaccum M, Charrier K, et al. (1999) RANK is essential for osteoclast and lymph node development. Genes Dev 13:2412–2424. 10.1101/gad.13.18.2412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boyle WJ, Simonet WS, Lacey DL (2003) Osteoclast differentiation and activation. Nature 423:337–342. 10.1038/nature01658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Estrela C, Holland R (2003) Calcium hydroxide: study based on scientific evidences. J Appl Oral Sci 11:269–282. 10.1590/S1678-77572003000400002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonson S, Jeansonne BG, Lallier TE (2004) Root-end filling materials alter fibroblast differentiation. J Dent Res 83:408–413. 10.1177/154405910408300511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Deus G, Ximenes R, Gurgel-Filho ED, et al. (2005) Cytotoxicity of MTA and Portland cement on human ECV 304 endothelial cells. Int Endod J 38:604–609. 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2005.00987.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braz MG, Camargo EA, Salvadori DMF, et al. (2006) Evaluation of genetic damage in human peripheral lymphocytes exposed to mineral trioxide aggregate and Portland cements. J Oral Rehabil 33:234–239. 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2005.01559.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rezende TMB, Vieira LQ, Cardoso FP, et al. (2007) The effect of mineral trioxide aggregate on phagocytic activity and production of reactive oxygen, nitrogen species and arginase activity by M1 and M2 macrophages. Int Endod J 40:603–611. 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2007.01255.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zaidi M, Troen B, Moonga BS, Abe E (2001) Cathepsin K, osteoclastic resorption, and osteoporosis therapy. J. Bone Miner. Res. 16:1747–1749. 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.10.1747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gelb BD, Shi G-P, Chapman HA, Desnick RJ (1996) Pycnodysostosis, a Lysosomal Disease Caused by Cathepsin K Deficiency. Science (80- ) 273:1236–1238. 10.1126/science.273.5279.1236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kiviranta R, Morko J, Uusitalo H, et al. (2001) Accelerated turnover of metaphyseal trabecular bone in mice overexpressing cathepsin K. J Bone Miner Res 16:1444–1452. 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.8.1444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zaidi M, Moonga B, Moss DW, MacIntyre I (1989) Inhibition of osteoclastic acid phosphatase abolishes bone resorption. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 159:68–71. 10.1016/0006-291X(89)92405-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moonga BS, Moss DW, Patchell A, Zaidi M (1990) Intracellular regulation of enzyme secretion from rat osteoclasts and evidence for a functional role in bone resorption. J Physiol 429:29–45. 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perez-Amodio S, Jansen DC, Schoenmaker T, et al. (2006) Calvarial osteoclasts express a higher level of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase than long bone osteoclasts and activation does not depend on cathepsin K or L activity. Calcif Tissue Int 79:245–254. 10.1007/s00223-005-0289-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheng X, Zhu L, Zhang J, et al. (2017) Anti-osteoclastogenesis of Mineral Trioxide Aggregate through Inhibition of the Autophagic Pathway. J Endod 43:766–773. 10.1016/j.joen.2016.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.da Fonseca TS, Silva GF, Guerreiro-Tanomaru JM, et al. (2019) Biodentine and MTA modulate immunoinflammatory response favoring bone formation in sealing of furcation perforations in rat molars. Clin Oral Investig 23:1237–1252. 10.1007/s00784-018-2550-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hashiguchi D, Fukushima H, Yasuda H, et al. (2011) Mineral Trioxide Aggregate Inhibits Osteoclastic Bone Resorption. J Dent Res 90:912–917. 10.1177/0022034511407335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hungaro Duarte MA, De Oliveira Demarchi ACC, Yamashita JC, et al. (2003) pH and calcium ion release of 2 root-end filling materials. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 95:345–347. 10.1067/moe.2003.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zaidi M, Adebanjo OA, Moonga BS, et al. (1999) Emerging insights into the role of calcium ions in osteoclast regulation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 14:669–674. 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.5.669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zaidi M, Alam ASMT, Shankar VS, et al. (1993) Cellular biology of bone resorption. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 68:197–264. 10.1111/j.1469-185X.1993.tb00996.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Datta HK, MacIntyre I, Zaidi M (1989) The effect of extracellular calcium elevation on morphology and function of isolated rat osteoclasts. Biosci Rep 9:747–751. 10.1007/BF01114813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bortoluzzi EA, Broon NJ, Bramante CM, et al. (2006) Sealing Ability of MTA and Radiopaque Portland Cement With or Without Calcium Chloride for Root-End Filling. J Endod 32:897–900. 10.1016/j.joen.2006.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Antunes Bortoluzzi E, Juárez Broon N, Antonio Hungaro Duarte M, et al. (2006) The Use of a Setting Accelerator and Its Effect on pH and Calcium Ion Release of Mineral Trioxide Aggregate and White Portland Cement. J Endod 32:1194–1197. 10.1016/j.joen.2006.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Naim JO, Van Oss CJ, Wu W, et al. (1997) Mechanisms of adjuvancy: I - Metal oxides as adjuvants. Vaccine 15:1183–1193. 10.1016/S0264-410X(97)00016-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Granchi D, Ciapetti G, Amato I, et al. (2004) The influence of alumina and ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene particles on osteoblast-osteoclast cooperation. Biomaterials 25:4037–4045. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.10.100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Granchi D, Amato I, Battistelli L, et al. (2005) Molecular basis of osteoclastogenesis induced by osteoblasts exposed to wear particles. Biomaterials 26:2371–2379. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.07.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]